Abstract

Objectives

The current research project sought to map out the regulatory landscape for patient safety in the English National Health Service (NHS).

Method

We used a systematic desk-based search using a variety of sources to identify the total number of organisations with regulatory influence in the NHS; we researched publicly available documents listing external inspection agencies, participated in advisory consultations with NHS regulatory compliance teams and reviewed the websites of all regulatory agencies.

Results

Our mapping revealed over 126 organisations who exert some regulatory influence on NHS provider organisations in addition to 211 Clinical Commissioning Groups. The majority of these organisations set standards and collect data from provider organisations and a considerable number carry out investigations. We found a multitude of overlapping functions and activities. The variability in approach and overlapping functions suggest that there is no overall integrated regulatory approach.

Conclusion

Regulation potentially provides a variety of benefits in terms of maintaining the safety and quality of care by providing an external perspective on the care being delivered. However, the variability, extent and fragmentation of the regulatory system of the NHS make it hard for regulators to act effectively and places a massive burden on NHS provider organisations. Overlapping regulatory requests may distract locally driven initiatives to improve safety and quality. Further research is needed to understand the full extent of regulatory activity and the true benefits and costs incurred.

Keywords: healthcare, regulation, patient safety, mapping, statutory regulators, regulatory functions

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to attempt a complete mapping of all organisations engaged in regulatory activities in the NHS.

We have included all statutory regulators but also many others who may not see themselves as regulators but nevertheless carry out regulatory activities.

Understanding the full regulatory landscape enables more precise assessment of the benefits and costs of regulation.

Due to resource constraints, we were only able to identify regulatory activities from the websites of the relevant organisations.

Although we have searched extensively, we cannot be sure that this is a complete mapping.

Introduction

Regulation is one important means of monitoring and improving the safety of healthcare with the aim of ensuring safe, reliable treatment for patients and a safe working environment for healthcare professionals. Regulation in healthcare takes a variety of different forms and is conducted by many different actors, from formal regulatory inspections to voluntary efforts to promote good practice. Regulatory processes and activities potentially provide valuable feedback to provider organisations, supporting improvement and ensuring that high standards of performance are maintained.1 Critics argue that although regulation may have valuable effects, it is too often ineffective,2 inflexible3 and generates ticking box behaviour and bureaucratic compliance.4

A number of organisations and commentators have called for reform, proposing that the regulatory system needs to be simpler, organised around a common approach to regulation and less burdensome for providers.5 6 However, before such broad proposals can be given, proper consideration of a fundamental question must be addressed. What is the nature and extent of the current system? In this study, we aimed to map the current regulatory system for patient safety in the NHS, including both statutory regulators and other organisations with regulatory influence. Understanding this landscape of regulation of safety is an essential preliminary to any rational reform of the regulatory system but has, to our knowledge, never been previously attempted.

Regulation, regulators and patient safety

The term ‘regulation’ can be viewed negatively and narrowly by those who are subject to regulatory oversight.7 In healthcare settings in particular, regulation can often be seen as intrusive and inefficient interference by external authorities that distracts from the important tasks of clinical care.8 However, activities of regulation are typically much broader and more constructive than this.9 10 Regulation represents a wide range of different activities that seek to shape motives and attitudes within organisations, as well as policies and protocols.11 In healthcare, regulatory activities can encompass everything from formal regulatory inspections, attempts to promote good practice, to efforts to support and initiate culture improvement.12 13 Moreover, regulatory activities are commonly engaged in by a diverse range of different actors and institutions across healthcare, from statutory regulators to national agencies to professional bodies and charitable organisations.

The regulatory landscape of healthcare is therefore complex and multifacetted. To begin mapping the current regulatory system around patient safety, it is necessary to define the scope of our enquiries. In this study, we define patient safety regulation as the processes engaged in by institutional actors that seek to shape, monitor, control or modify activities within healthcare organisations in order to reduce the risk of patients being harmed during their care. This definition aims to focus attention on the specific activities that are engaged in by ‘external’ actors to influence ‘internal’ processes of patient safety in healthcare organisations. It also aims to encompass the breadth of diverse institutional actors that engage in these processes of regulation, even when some of those actors may not define themselves as formal ‘regulators’.

Evolution of regulation in the NHS

Before continuing to the mapping process, it is important to provide a brief historical perspective on regulation across the NHS. The 1944 National Health Service White Paper recognised that regular inspections of hospitals would be valuable but the first true external oversight body was not established until 1969, following a series of healthcare scandals.14 Until the late 1970s, the Department of Health fulfilled most of the regulatory functions, but between 1979 and 1997, the conservative administration created a number of regulatory bodies (such as the NHS Litigation Authority, now NHS Resolution). However, broad sectors of the NHS remained free of statutory external oversight or regulation throughout this period.15

Several high-profile failures of care in the 1990s (including the problems at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, Royal Liverpool Children’s Hospital) eroded public trust in the NHS. The labour government adopted a more interventionist approach to regulation, increasing the depth, detail and complexity of inspection processes.5 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) was established in 1999 and the Commission for Health Improvement, the ancestor of the Care Quality Commission (CQC), was founded in 2001 to oversee and inspect the clinical quality of all NHS services. The 2013 Francis report on the Mid Staffordshire failings of care was a defining moment for the whole regulatory regime which had failed to detect and respond to early signs of organisational failure.16 The governmental response generated more structural changes to the system, with an increased focus on devolution of central oversight.

The evolution of regulation in the NHS needs to be seen in the context of continual widespread reform and restructuring of the wider NHS. In 2002, the National Health Service Reform and Healthcare Professionals Act merged 95 health authorities into 28 strategic health authorities (SHAs).17 In 2006, the number of SHAs reduced to 10 and later transformed into four clusters (North, South, Midlands and East of England) before finally been abolished in April 2013.18 During this time, health services commissioning was undertaken by 481 Primary Care Groups, later reduced to 152 Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in 2002, solely responsible for all NHS commissioning.17 Finally, under the Health and Social Care Act in 2012, PCTs were replaced by statutory, commissioning ‘consortia’, the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs).19

The 5-year forward review20 brought the planning and regulation of primary, secondary and social care together with local authority influence under seven models of care each covering a core set of related services (for instance, urgent and emergency care networks). Local leaders in 44 geographical areas have been asked to design sustainability and transformation plans (STPs) to demonstrate how they intend to transform services in their local areas.21 Ten integrated care systems (ICSs) have evolved from STPs, responsible for planning and commissioning care for their populations.22

The need to map the regulatory landscape of the NHS

This short overview of regulation history in the UK demonstrates a stream of structural reforms over the last 25+ years, which have gradually increased the extent and complexity of the regulatory structures.16 23 In 2002, Walshe argued that: ‘Current regulators vary widely in their statutory authority, powers, scope of action, and approach. The resulting mosaic of regulatory arrangements is highly fragmented and some roles are duplicated’.24 Since then, the complexity of the system has increased considerably. A report from the NHS confederation argued that this complexity places an unnecessary burden on healthcare organisations when, for example, different regulators request evidence for similar safety standards.25 The Professional Standards Authority has pointed out that all the nine bodies they oversee have a common set of functions yet there are differences in legislation, standards, approach and efficiency, among others.6

In this study, we attempted to map the complete landscape of all organisations with patient safety regulatory effect on NHS providers and consider the impact of this system on NHS provider organisations. This means identifying all organisations which exert regulatory influence, not just those designated as statutory regulators. In our preliminary inquiries, it appeared that no one, not even regulatory organisations, had a complete understanding of all the bodies with regulatory impact on the NHS.

Methodology

Defining safety regulation

We intended to examine all institutional actors that sought to have some form of regulatory impact on healthcare organisations. This of course includes agencies with statutory responsibilities, but many other organisations exert regulatory influence through standard setting, analysis and feedback of data, inspection and other activities. To capture this wider landscape, we defined organisations with regulatory impact as those who fulfilled all of the following four criteria:

Consider the improvement of patient safety a part of their organisational responsibilities.

Undertake some form or monitoring or oversight of safety-related standards or performance.

Engage in formal attempts to influence the safety performance of NHS provider organisations (there are various ways this can be achieved in practice).

Derive some form of legitimacy or external authority for their work on safety.

Mapping process

We used a variety of sources to gradually build up a picture of the patient safety regulatory landscape of the NHS. First, we identified publicly available documents listing external inspection agencies for five NHS Trusts—two community, two acute and one mental health. These lists summarise regulatory visits, inspections, assessments and accreditations made by regulatory bodies. This exercise provided an initial list of regulatory agencies. The Trusts themselves admitted that they were not sure of how many agencies were visiting them or requiring information. Advisory consultations with members of Trusts’ regulatory compliance teams complemented the final list of agencies involved in overseeing healthcare providers.

We then scanned the official websites of all statutory regulatory agencies. We also searched for existing collaborations and partnerships with other institutions which increased the number of organisations detected.

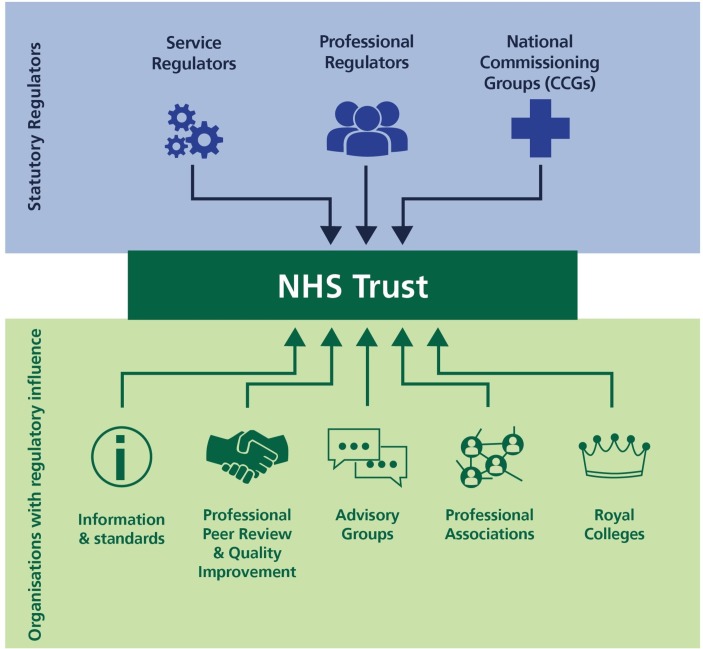

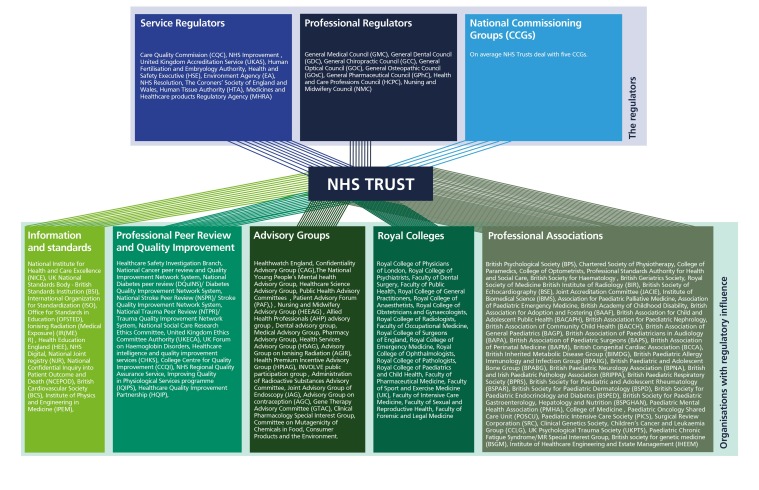

The review eventually evaluated over 200 organisations, in some way involved in overseeing healthcare together with over 200 CCGs. We refined this list to include only those organisations meeting the four inclusion criteria set out above. We then classified all these organisations under three broad categories according to their core aim (1) statutory regulators of services, such as CQC, (2) statutory regulators of professionals, such as the General Medical Council, and (3) organisations with regulatory influence and effect (such as Royal Colleges and standard setting organisations) (figure 1). In case organisations fell under more than one cluster, a decision was reached through discussions among members of the research group.

Figure 1.

Overview of healthcare regulation map.

Describing regulatory activities of organisations

To gain a more in-depth understanding of the patient safety-related activities these organisations carry out, we documented how they monitor professional performance, the way they evaluate compliance with standards and what actions are involved in approaching perceived deficiencies (eg, enforcement sanctions, public ratings, legal prosecution and so on).

We reviewed a variety of sources; official websites, statutory instruments, reports and other records (eg, information enfolded in various electronic domains such as annual reviews, strategic plans, meeting minutes and so on) and identified a list of external oversight functions. We then simplified the list by removing duplicates and combining activities which were essentially similar but described in different ways by different organisations. We additionally consulted a small advisory group of healthcare regulation experts, both practitioners and researchers, to reach consensus on classifying the activities into a more concise list. Based on consensus among the authors, all regulators and regulatory actors carry out 15 overseeing functions (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Regulatory activities and definitions.

Patient and public involvement

A small advisory group with patient representatives supported the design of the project. Preliminary findings were presented to a larger seminar at the Health Foundation with several patient representatives present.

Results

Our mapping revealed that over 126 organisations exert some safety regulatory effect on NHS provider organisations in addition to Health Services Commissioners; 211 CCGs and 10 ICSs (figure 3). Of the 126 organisations we identified, 3 are national overseeing bodies, 18 are statutory regulators and 104 are organisations with regulatory effect which makes a total of 125. The 126th entity, is a grouping of all the national Health Services Commissioners; 211 CCGs and 10 ICSs. We emphasise that many of these organisations would not see themselves as regulators and indeed regulation is usually not their primary function. They do all nevertheless exert some regulatory influence on the NHS. The extent of their influence and activity varies widely and only a proportion of these organisations may be in contact with any one NHS Trust. A full list of organisations identified is presented online in supplementary appendix figure 1.

Figure 3.

Regulators and organisations with regulatory influence.

bmjopen-2018-028663supp001.jpg (4.1MB, jpg)

Oversight of the system

Three national bodies that fund, lead and support healthcare in England; Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England and Public Health England (PHE).

The DHSC is a ministerial department responsible for overseeing the system and is supported by 28 arm’s length bodies.26 NHS England oversees the operation of 211 CCGs and directly commissions specialist services and primary care including GPs, pharmacists, dental practices, military and a number of local health services. Its main role is to set the priorities and direction of the NHS and to improve health and care outcomes for people in England. PHE is an executive agency of the DHSC with operational autonomy. PHE works with local government, parliament, industry and national bodies to support public health services such as immunisation and screening programmes.

Health services commissioners

Clinical Commissioning Groups

CCGs are independent, NHS statutory bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of healthcare services within their local area. Each NHS provider organisation will work with only a limited number of CCGs, which may vary in their remit and functions.

The majority of health services, including emergency care, elective hospital care, maternity services, community and mental health services and general practices are commissioned by the CCGs.27 Currently, there are 211 CCGs in England, responsible for 2/3 of the total NHS England budget. CCGs operate as a strong influencer for improving patient safety at provider level through their role in seeking assurance providers are meeting safety standards.

Integrated care systems

Ten ICSs are involved in the wider health services commissioning landscape as they bring together NHS providers, commissioners and local authorities to work in partnership for improving health and care in their area.22 ICSs are led by NHS and local government leaders and are based on voluntary collaboration. Their principal functions are aligning commissioning plans; incorporating the regulatory functions of NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSI) and planning and managing performance in their areas. Responsibility for service delivery rests with the organisations that provide care within ICSs and many of these organisations are collaborating to put in place integrated care plans.22

Statutory regulators

Statutory regulators operate with a mandate to oversee organisations, services, professionals and healthcare products. They often develop quality standards, offer accreditation services and support professionals through education and training. The full list of statutory regulators is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Statutory regulators of the NHS

| Services regulators: 10 | Professionals regulators: 8 |

| Care Quality Commission | General Medical Council |

| NHS Improvement | General Dental Council |

| United Kingdom Accreditation Service | General Chiropractic Council |

| Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority | General Optical Council |

| Health and Safety Executive | General Osteopathic Council |

| Environment Agency | General Pharmaceutical Council |

| NHS Litigation Resolution | Health and Care Professions Council |

| The Coroners' Society of England and Wales | Nursing and Midwifery Council |

| Human Tissue Authority | |

| Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency |

Regulators of services

Ten statutory bodies oversee healthcare systems and clinical settings such as hospitals, care homes and general practices. Their scope of functions includes providing standards and guidelines as well as monitoring healthcare providers’ safety performance to establish compliance with policies and quality standards. They have statutory powers to impose enforcing measures which span from suspension or removal from the registry in case of non-compliance to criminal prosecution and penalties.

CQC is the primary healthcare regulator in England. It is an independent agency, established in 2009 and is responsible for registering, inspecting, monitoring and rating services of healthcare providers in England. Its central role includes investigating, licencing and collecting clinical data and performance metrics that could reveal problems within services.

NHSI is a non-departmental agency monitoring financial and operational functions across the health sector. NHSI works closely with CQC in holding NHS boards to account and providing support to providers under-or at risk of being under special measures, by designing strategies to improve their performance.28

Other organisations of this cohort are involved in assessing, accrediting and licencing healthcare services. For example, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) is the statutory body that regulates and inspects all in vitro fertilisation healthcare settings, assessing compliance and publishing policy papers.29 The Health and Safety Executive (HSE), is a body responsible for regulating workplace health and safety and NHS Resolution (Former NHS Litigation Authority) is an organisation that manages complaints and negligence claims against the NHS.30 Equally, the Environment Agency (EA) is accountable for medical waste regulation31 and Coroners and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency are both involved in serious incidents investigations making inquiries into healthcare providers and enforcing sanctions.32 33

Regulators of professionals

Eight statutory bodies oversee the practice of healthcare professionals. Professional regulators have multiple responsibilities in addition to strictly regulatory activities. They also seek to improve education and training, provide support to health professionals throughout their professional career, from mentoring during training, to emotional support services during investigations. Regulatory functions include registering of professionals, revalidation, training and imposing sanctions where necessary.

The Professionals Standards Authority (PSA) oversees the above eight regulators. PSA is an independent body, accountable to the parliament and it sets standards for those organisations that maintain voluntary registers and accredits those that meet them.34 Although their scope of action includes monitoring regulators’ performance, conducting audits, reviewing decisions regarding fitness to practice and reporting to Parliament, they do not identify themselves as a regulator. PSA can apply conditions and suspend or remove accreditation from healthcare professionals but does not have the statutory power to investigate complaints about the regulators they oversee.19

Organisations with regulatory influence

We found 104 other organisations that critically seek to influence the safety performance of NHS provider organisations. These organisations do not, for the most part, see themselves as regulators. However, these organisations meet the four criteria set out above, being concerned with patient safety, seeking to influence standards and deriving some form of external legitimacy. They therefore exert regulatory influence on provider organisations.

While they do not see themselves as regulators, these organisations nevertheless carry out some regulatory activities (table 2) and have a significant impact on healthcare provider organisations. The group comprises national agencies (eg, NICE), professional bodies (eg, Royal College of Physicians), patient organisations and charities exerting regulatory effects through norm-setting, monitoring and support (eg, Healthwatch England, Action Against Medical Accidents). Table 2 summarises the institutions with regulatory effect.

Table 2.

Organisations with regulatory influence

| Categories | No of organisations | |

| Information and standards | 11 | Operate with a mandate to develop national standards and recommendations through evidence-based research, in collaboration with healthcare experts’ teams. |

| Professional peer review and quality improvement | 13 | Health professional networks, aiming to promote collaboration between healthcare organisations. |

| National advisory groups | 21 | Engaged in improving quality of care delivered to patients by providing a range of strategic professional advice and expertise. |

| Royal Colleges | 19 | Membership organisations and professional bodies that promote quality standards and support professionals through education and training. |

| Professional associations | 40 | Professional associations are commonly multidisciplinary societies with voluntary registration status that promote the interests of the group they represent. |

| Total: 104 |

The majority of these organisations set standards of some kind with which they seek to influence provider organisations. Most collect data from provider organisations and a considerable number carry out investigations of some kind when circumstances require. A few can use sanctions such as the withdrawal of accreditation. Table 2 provides a summary of the various regulatory activities of each category of the influencing organisations.

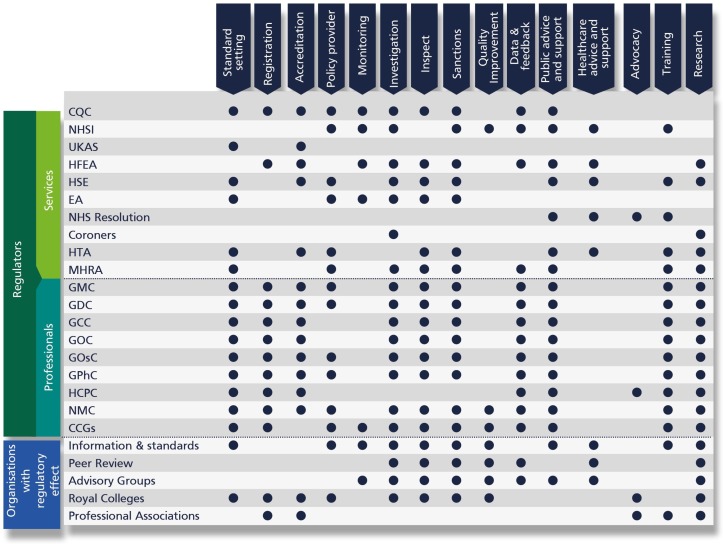

Functions and activities of the wider regulatory landscape

Figure 4 shows the different patterns of regulatory activity for all the organisations which can influence providers’ behaviour. The multitude of organisations that are simultaneously involved in various types of activities overseeing healthcare is striking.

Figure 4.

Regulatory functions and activities. CCGs, Clinical Commissioning Groups; CQC, Care Quality Commission; EA, Environment Agency; GCC, General Chiropractic Council; GDC, General Dental Council; GMC, General Medical Council; GOC, General Optical Council; GOsC, General Osteopathic Council; GPhC, General Pharmaceutical Council; HCPC, Health and Care Professions Council; HFEA, Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority; HSE, Health and Safety Executive; HTA, Human Tissue Authority; MHRA, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; NHSI, NHS Improvement; NMC, Nursing and Midwifery Council; UKAS, United Kingdom Accreditation Service.

All eight professional regulators offer accreditation services, register healthcare professionals, provide standards of care, collect performance data, conduct research and carry out investigations in case of complaints against a practitioner. These organisations perform broadly similar functions, as one might expect, although this does not mean that they carry out activities in the same way or have the same underlying model of regulation.

The activities of the regulators of services are much more varied. There is no reason to think that all these organisations should do exactly the same thing, but the variability in approach and overlapping functions suggest that there is no overall integrated regulatory approach. Inspections for assessing the quality of care, for instance, are undertaken by a variety of agencies, non-governmental, governmental and regional that use different methods. The inspection process can take different forms, both in terms of measurements, review focus and data used.

Overlapping functions and activities

There are a multitude of overlapping functions and activities and we can only provide a small number of examples here. We identified several local or national organisations from the wider landscape responsible for inspection visits, accreditation assessments, with a remit to impose sanctions that specifically relate to patient safety. These covered safety inspections of specific clinical services or against national standards (eg, inspections by CQC and NHS Resolution), health and safety issues like fire standards, quality of training of junior doctors, granting licences and accreditation for sterile services, local postmortem and blood transfusion services, audits of internal governance structures and so on. Some of the organisations listed, carry out separate inspections of different services. For example, the Royal College of Psychiatrists carry out inspections against standards for mental health in-patients, high-security mental health units and electroconvulsive treatment units. Similarly, in the acute care setting, Clinical Pathology Accreditation UK may conduct separate visits for histopathology and cytology and haematology services.

Investigation of serious incidents and complaints is the regulatory function performed by the majority of overseeing agencies. Agencies from both the regulators group and the wider landscape are involved in investigating activities either by conducting these themselves, or by overseeing the quality of serious incident investigations and ensuring action plans are completed.

Although a multitude of overseeing agencies conduct or oversee investigations, not all of them exert the power to impose sanctions. Specifically, only CQC, NHSI, HFEA, HSE and EA have the authority to impose sanctions and enforcement measures to health provider organisations.

Discussion

In this research project, we have documented the regulatory bodies engaged in influencing organisational performance. We divided the landscape into two broad categories; the main regulatory bodies with direct, statutory responsibilities, such as the Care Quality Commission or the Nursing and Midwifery Council, and other organisations that carry out some regulatory activities but have a more indirect influence, such as the Royal Colleges. We found that in total, more than 126 organisations are engaged in safety related regulatory activities in the NHS. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to carry out a full mapping exercise of healthcare regulatory actors in England.

The existence of multiple regulatory actors,13 the complexity and rapid changes of the regulatory environment35 and influences on healthcare practice36 and service delivery37 have been widely documented in various health systems, for example, England, Australia and New Zealand.38 Healthcare providers often find themselves accountable to a variety of uncoordinated large scale data enquiries.39–41 Such enquiries often create duplication of work and can undermine the relationship of regulators and those on the receiving end.

NHS provider organisations in healthcare are often faced with a wide range of disparate organisations and agencies all of whom play some role in the creation, monitoring and enforcement of safety standards; governmental agencies, organisations regulating professionals, manufacturers and suppliers of drugs and equipment, charities, patient advocacy groups, accreditors, professional associations, information technology groups and various others.42 These nested networks typically find it difficult to coordinate their interactions43 which can create confusion on the receiving end and sometimes divert resources into ineffective improvement efforts.42 44 Evidence of overlapping responsibilities, duplication, practical challenges in coordinating regulatory compliance and providing assurance have been extensively documented.29–32 For example, drawing on interviews with 47 NHS organisations, Walshe24 noted that Trusts were ‘concerned about the time required and workload involved in producing the portfolio of evidence’.9 The findings of this mapping exercise suggest that trusts are potentially dealing with large numbers of organisations when assembling this evidence and responding to requests.

New institutional actors, such as the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB), are emerging. HSIB is purposefully positioned outside the existing regulatory structures that surround patient safety in the English NHS, and actively seeks to investigate and examine the sources of serious risks to patient safety that emerge across the healthcare system, and make recommendations to a range of actors regarding how the healthcare system might be improved. An intentional focus is on investigating and improving regulators and the regulatory system itself.45 It remains to be seen how these activities will unfold and whether independent, system-wide investigators are able to influence change and improvement to individual regulators and the regulators landscape as a whole.

Our research suggests that studies that have examined the benefits and burdens of regulation may have considerably underestimated the overall impact on NHS Trusts. Future empirical studies evaluating the benefits and burdens of regulation might need to look beyond the impact of statutory regulators and consider the effect of the wider regulatory landscape set out here. This mapping will also enable more targeted studies of the regulatory process in which the specific activities of the multiple organisations engaged can be examined. Arguably, the true costs, benefits and burden of regulation in the NHS have never been properly assessed. Future research should carry out a full assessment and costings of the time spent by trusts in responding to regulatory requests of all kinds and from all relevant organisations, including both statutory regulators and those with regulatory influence. The costing should obviously include both resources used by regulatory organisations and those they regulate. Only after such an exercise will we be able to see what proportion of the NHS budget is truly devoted to regulation.

Conclusion

In this project, we have mapped out the regulatory landscape for patient safety in the NHS. Although we identified a wide array of organisations with regulatory influence through an exhaustive review process, we cannot be sure that we identified all organisations exerting any regulatory effect. The regulatory system of the NHS has evolved rather than been designed and is not fully understood even by professional regulators and it is almost impossible for the general public to navigate the system. Regulation is important and the actions of thoughtful and well-intentioned regulatory organisations have the potential to improve health service standards. However, the overall impact of the regulatory system hinders the effectiveness of regulatory actors and can be challenging for NHS providers detracting from safety and quality improvement initiatives. A full analysis of the time and resource devoted to safety regulations, and an assessment of the costs and benefits, would be a major undertaking but could potentially lead to a major simplification of the current system, which in turn could produce much more effective and responsive regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Elizabeth Raby who designed the illustrations for this paper and the members of a project related seminar held at the Health Foundation in November 2017, who gave us invaluable feedback on our initial mapping exercise. We would also like to thank Professor Judith Healy and Miss Catherine Mooney for reading the full report of this project and for offering their thoughtful feedback.

Footnotes

Contributors: CV, JC and CM conceptualised the study. CV oversaw the scientific direction. EO conducted the mapping process. CV, JC and CM contributed to the final categorisation of organisations. EO drafted the paper. CV, JC and CM revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Health Foundation (90 Long Acre, London, WC2E 9RA). Email: info@health.org.uk. Grant number: 7531.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Gunningham N. Regulatory reform and reflexive regulation: beyond command and control. Reflexive governance for global public goods: MIT Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flodgren G, Pomey M-P, Taber SA, et al. Effectiveness of external inspection of compliance with standards in improving healthcare organisation behaviour. 2011. www.cqc.org.uk/ (cited 9 Dec 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Brennan TA. The role of regulation in quality improvement. Milbank Q 1998;76:709-31, 512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braithwaite J, Coglianese C, Levi-Faur D. Can regulation and governance make a difference? Regul Gov 2007;1:1–7. 10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00006.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edwards N. Burdensome regulation of the NHS. BMJ 2016;353:i3414 10.1136/bmj.i3414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Professional Standards Authority. Rethinking regulation. 2015. www.professionalstandards.org.uk (cited 9 Dec 2018).

- 7. Braithwaite V. Ten things you need to know about regulation but never wanted to ask. 2006. http://regnet.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2015-07/10thingswhole.pdf (cited 4 Mar 2019).

- 8. Macrae C. Reconciling Regulation and Resilience. In Hollnagel, E., Braithwaite, J., and Wears, R. (Eds). In Ashgate. 2013. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=8AWiAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT20&dq=Reconciling+Regulation+and+Resilience.&ots=TN2oLA8dMl&sig=vdzmbsvuWhaFc53y46QXsK5b_7Q#v=onepage&q=Reconciling Regulation and Resilience.&f=false (cited 14 Mar 2019).

- 9. Braithwaite J. The Essence of Responsive Regulation. Vol. 44, U.B.C. Law Review. 2011. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/ubclr44&id=489&div=29&collection=journals (cited 14 Mar 2019).

- 10. Macrae C. Regulating resilience? Regulatory work in high-risk arenas. In Hutter, B. (Ed). In: Anticipating Risks and Organising Risk Regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UUTwV4_NVe4C&pg=PA139&lpg=PA139&dq=Regulating+resilience?+Regulatory+work+in+high-risk+arenas.&source=bl&ots=mauzijtVwC&sig=ACfU3U1sRwVdCG5mA1ubYZuLrREUF1p5Bw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjKmomYjILhAhVFSBUIHfPODT8Q6AEwAnoECAcQ (cited 14 Mar 2019).

- 11. Shearing C. A constitutive conception of regulation. In P. Garbosky and J. Braithwaite (eds.) Business Regulation and Australia’s Future. In Australian Institute of Criminology. 1993. https://www.anu.edu.au/fellows/jbraithwaite/_documents/Articles/Business Regulation and Australias Future.pdf#page=79 (cited 14 Mar 2019).

- 12. Mello MM, Kelly CN, Brennan TA. Fostering rational regulation of patient safety. J Health Polit Policy Law 2005;30:375–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Healy J. Improving Health Care Safety and Quality: Reluctant Regulators - Dr Judith Healy - Google Books. Aldershot: Ashgate. 2011. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Improving_Health_Care_Safety_and_Quality.html?id=HYh6BgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (cited 14 Mar 2019).

- 14. Walshe K, Higgins J. The use and impact of inquiries in the NHS The development of NHS inquiries. BMJ 2002;19:895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walshe K. Regulation and Inspection of Health Services In: Martin, S, & Davis, H, eds. Public Services Inspection in the UK. London, UK. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2008. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=7_wPBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Regulation+and+Inspection+of+Health+Services.+In:+Martin,+S,+%26+Davis,+H,+eds.+Public+Services+Inspection+in+the+UK.+London,+UK&ots=Q1NxlK6BG-&sig=EwjBy7hreC_12govepqpEyZskQM#v=o (cited 9 Dec 2018).

- 16. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: executive summary: Stationery Office, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Health Foundation. The national health service reform and health care professionals act 2002 | Policy Navigator. Policy Navigator. https://navigator.health.org.uk/content/national-health-service-reform-and-health-care-professionals-act-2002

- 18. Turner D, Powell T. What is NHS commissioning? The origins of NHS commissioning. 2002. www.parliament.uk/commons-library%7Cintranet.parliament.uk/commons-library%7Cpapers@parliament.uk%7C@commonslibrary (cited 5 Mar 2019).

- 19. Naylor C, Curry N, Holder H, et al. Clinical commissioning groups: supporting improvement in general practice? https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/clinical-commissioning-groups-report-ings-fund-nuffield-jul13.pdf. 2013

- 20. NHS. Five year forward view. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

- 21. Ham C, Alderwick H, Edwards N, et al. Sustainability and transformation plans in London. 2017. www.kingsfund.org.uk [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. The King’s Fund. Making sense of integrated care systems, integrated care partnerships and accountable care organisations in the NHS in England. 2018. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/making-sense-integrated-care-systems

- 23. Berwick D. A Promise to Learn–a commitment to act: Improving the Safety of Patients in England. London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walshe K. The rise of regulation in the NHS. BMJ 2002;324:967–70. 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. NHS Confederation. What’s it all for? Reducing unnecessary bureaucracy in regulation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Audit Office. A Short Guide to: Selected health arm’s-length bodies. 2017. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/A-Short-Guide-to-Selected-health-arms-length-bodies.pdf (cited 9 Dec 2018).

- 27. The King’s Fund. Ideas that change health care. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/ (cited 20 Aug 2011).

- 28. NHS Improvement. From 1 April, NHS Englandopens and NHS Improvement come together to act as a single organisation. Our aim is to better support the NHS and help improve care for patients. https://improvement.nhs.uk/

- 29. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Welcome to the HFEA. https://www.hfea.gov.uk/ (cited 13 Dec 2018).

- 30. Health and Safety Executive. Information and services. http://www.hse.gov.uk/ (cited 13 Dec 2018).

- 31. Environment agency. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/environment-agency/about (cited 2018 Dec 13).

- 32. The Coroners’ Society of England & Wales. Welcome to the Coroners’ Society of England & Wales. https://www.coronersociety.org.uk/ (cited 13 Dec 2018).

- 33. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Latest from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/medicines-and-healthcare-products-regulatory-agency (cited 13 Dec 2018).

- 34. Professional Standards Authority. We oversee regulators. https://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/home (cited 13 Dec 2018).

- 35. Healy J, Braithwaite J. Designing safer health care through responsive regulation. Med J Aust 2006;184:S56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quick O. Regulating and legislating safety: the case for candour. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:614–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Quick O. A scoping study on the effects of health professional regulation on those regulated. 2011. https://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/docs/default-source/publications/research-paper/study-on-the-effects-of-health-professional-regulation-on-those-regulated-2011.pdf

- 38. Healy J, Walton M. Health ombudsmen in polycentric regulatory fields: England, New Zealand, and Australia. Aust J Public Adm 2016;75:492–505. 10.1111/1467-8500.12187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hood C, James O, Scott C. Regulation of Government: Has it Increased, is it Increasing, Should it be Diminished? Public Adm 2000;78:283–304. 10.1111/1467-9299.00206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hampton P. Reducing administrative burdens: effective inspection and enforcement: HM Stationery Office, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martin SJ. Regulation inside government: processes and impacts of inspection of local public services. 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27649747 (cited 13 Dec 2018).

- 42. Dixon-Woods M, Pronovost PJ. Patient safety and the problem of many hands. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:485–8 http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klijn E-H, Koppenjan J. Complexity in governance network theory. Complexity, Gov Networks 2014;1:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Austin JM, Jha AK, Romano PS, et al. National hospital ratings systems share few common scores and may generate confusion instead of clarity. Health Aff 2015;34:423–30. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Macrae C, Vincent C. Learning from failure: the need for independent safety investigation in healthcare. J R Soc Med 2014;107:439–43. 10.1177/0141076814555939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028663supp001.jpg (4.1MB, jpg)