Abstract

Introduction

Over the past decades, the number of people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) has increased globally. One of the major complications in these patients is cardiovascular disease; it seems that the cell proliferation inhibition can improve vascular function in these patients. It is proposed that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) can induce cell cycle arrest via cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16) activation. Also, it has been shown that phosphorylated tumour suppressor protein p53 is involved in cell senescence by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21) upregulation. Resveratrol is a natural polyphenol and appears to improve the vascular function through the mentioned pathways. We will aim to evaluate the effects of resveratrol supplementation on mRNA expression of PPARα, p53, p21 and p16 in patients with T2D. We will also measure serum levels of cluster of differentiation 163 (CD163) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) as the indicators of cardiovascular status.

Methods and analysis

Seventy-two subjects suffering from T2D will participate in this double-blind randomised parallel placebo-controlled clinical trial. Participants will be randomly assigned to receive 1000 mg/day trans-resveratrol or placebo (methyl cellulose) for 8 weeks. The mRNA expression levels of PPARα, p53, p21 and p16 genes will be assessed using real-time PCR and serum CD163 and TWEAK levels will be measured using commercially available ELISA kits at baseline and the end of the study. Clinical outcome parameters (glycaemic and lipid profiles and body composition) will also be measured before and after study duration.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and is approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (no: ir.ssu.sph.rec.1396.120). The results will be published in scientific journals.

Trial registration number

IRCT20171118037528N1; Pre-results.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, resveratrol, peroxisome proliferator activated receptors, P53, P16

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first human study to investigate the effects of resveratrol supplementation on the cellular factors associated with intimal hyperplasia through the cellular pathways.

This study is the first trial that uses resveratrol as a natural ligand for PPARα.

This study is not designed to follow-up the patients to determine the long-term effects of resveratrol supplementation.

Introduction

With an increasing trend in its prevalence, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has become one of the important causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1–3 Uncontrolled T2DM might lead to a broad range of micro- and macrovascular complications such as vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular disease (CVD).4–6 Atherosclerosis is one of the most important causes of CVD which leads to intimal hyperplasia (IH).4 IH is a cardinal manifestation of atherosclerosis which is associated with CVD, and recently it has been suggested to be added to the Framingham risk factors.7 In addition, IH might lead to restenosis after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or vascular graft and it is known as one of the major complications during the treatment of CVD.8–10 Proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) is increased during IH and is in accordance with vascular stenosis and heart attack.11 Recent animal studies indicated that the VSMCs’ proliferation inhibition through cell cycle arrest can reduce the IH levels.12 13

Some cellular studies suggest that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) also play a key role in VSMCs’ proliferation.14 15 PPARs are a group of nuclear receptors with various isoforms, including α, β/δ and γ that are involved in transcription regulation of a broad range of genes.16 17 PPARα is one of the members of this family and has a critical role in the regulation of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, glucose metabolism, vascular function, obesity, cell proliferation, plaque stability and inflammation.18 19 Some bodies of evidence showed that PPARα activation might arrest the cell cycle progression in G1/S phase through induction of the p16INK4a.6 15 Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, which is also known as p16INK4a, is a tumour suppressor that inhibits CDK4-mediated phosphorylation of retinoblastoma and inhibits induction of E2F-dependent genes and therefore suppresses cell cycle progression.20–22

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene), which is structurally known as stilbenoid and phytoalexin, is a type of natural polyphenol found mostly in red grapes; it has been introduced as a ligand of PPARα and it seems to stimulate cellular senescence via the above mentioned pathways.23–25 It has also been proposed that resveratrol has the potential to activate p53, another important tumour suppressor, by phosphorylating the serine residue in p53 protein through extracellular kinases.26 27 Phosphorylated p53 is proposed to be able to upregulate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21) gene, thereby inhibiting CDK2 activity and induces the cell cycle arrest in S to G2 phase.28 29 Animal studies indicated that p53 plays a key role in decreasing the intimal thickness.30–33

Insulin resistance induces chronic inflammation via increased macrophage activity and overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.34 Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) is a member of TNF superfamily which is mainly produced by macrophages and is released into the circulation in its soluble form (sTWEAK).35 Studies have shown that sTWEAK levels are reduced in T1DM, T2DM as well as in the presence of CVD risk factors.36–38 The main cause of reduced sTWEAK levels is its binding to fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14) receptor, which therefore can result in inflammatory responses.39

Intraplaque haemorrhage—common feature of atherosclerotic plaques—is prevalent in patients with T2DM.40 41 Studies have shown that intraplaque haemorrhage is most likely to occur in unstable plaques and is associated with ischaemic stroke.42–44 On the other hand, cluster of differentiation 163 (CD163) is a macrophage scavenger receptor that is involved in the uptake of haemoglobin–haptoglobin complexes and is also known as a scavenger of sTWEAK45 46; sCD163 is the soluble form of this receptor and it has been proposed that sCD163/sTWEAK ratio can be used as an indicator of the severity and progression of vascular diseases.36 47 48 Resveratrol, as an antioxidant, can reduce inflammatory responses and macrophages activity49 and thus, it seems that resveratrol might affect sCD163/sTWEAK ratio in patients with T2DM. Given that no study has investigated this issue, this has prompted us to design a randomised clinical trial (RCT) with the following objectives:

To investigate the effect of resveratrol supplementation on the changes in PPARα, p16, p53 and p21 gene expression as well as serum levels of sCD163 and sTWEAK in patients with T2DM.

To compare the changes in serum levels of lipid profile, including triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) as well as glycaemic control indices including fasting blood sugar, fasting insulin, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), pancreatic beta cell function and atherogenic index of plasma between the intervention and control groups.

Methods and analysis

Study design

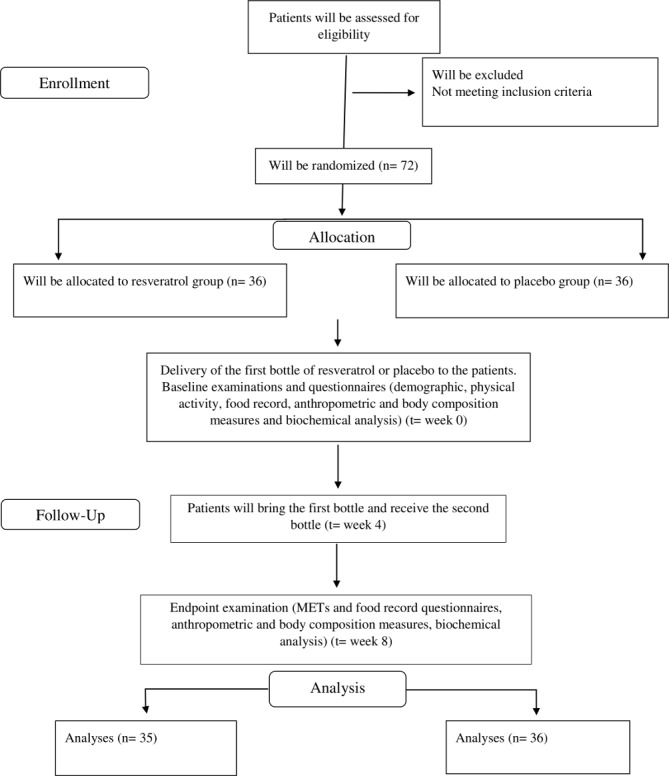

We designed a double-blind, randomised parallel placebo-controlled clinical trial among patients with T2DM; we will randomly assign patients to receive either 1000 mg resveratrol or placebo in a daily manner for 2 months. This monocentral study will be conducted in Diabetes Clinic Center in Yazd, Iran. The overall overview of the study is presented in figure 1. Any methodological changes in the study design or sample size, which may potentially affect the patients’ safety or study procedures, will be discussed in the committee of ethics before implementation.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study.

Randomisation

The present study will be an 8-week double-blind parallel RCT; patients will be randomised 1:1 according to the method of stratified block randomisation based on sex (male and female) and age (30–45 and 45–60 years).

Computer-generated random numbers will be used to randomly allocate eligible participants into the one of the two trial groups by an independent statistician. Participants will be allocated to one of the two arms, using sealed envelope by a researcher who will not be involved in participant’s enrolment (EKN) and assignment of intervention will be carried out by principal investigator (SA) who will be blinded to allocation. Resveratrol supplements and placebo will be provided in the same shape, colour and appearance and will be packed in the same bottles and a person, who is not involved in this project, will label the containers as A or B. Participants and administrator will be unaware about the content of the bottles until data analyses.

Eligibility criteria

Thirty to sixty-year-old men and women, who have been diagnosed with established T2DM for at least 3 months prior to the intervention and are taking medication for diabetes, will be invited to participate in the study. Participants with the following criteria will be excluded: (1) diagnosis of any liver, kidney, cancer and Alzheimer’s diseases or gastrointestinal ulcer; (2) pregnancy or lactation; (3) insulin therapy or the HbA1c levels at or above 8% at any point of study; (4) consumption of supplements containing fish oil, vitamin E or C in the previous 6 months; (5) a history of allergic reaction to grapes; (6) consumption of anticoagulants, fibrates and anti-inflammatory agents; (7) a history of myocardial infarction or the presence of stent or battery in patients’s heart and (8) consumption of red wine or supplements containing resveratrol in 6 months prior to intervention.

Sample size

Sample size is calculated based on a previous human study regarding the PPARα expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) as the primary variable.50 The participant numbers needed in each group is calculated using a proposed formula for parallel clinical trials by considering α=0.05 and a power of 80%.51 Assuming a 20% of dropout rate, the final sample size is set to be 36 participants in each group.

Intervention

Recruitment of participants will take place through installing announcements at Diabetes Clinic Center in Yazd, Iran. Interested patients will be invited to a screening session and two trained researchers (SA and MT) will introduce the study protocol to them and assess eligibility criteria. Written consent form will be obtained from all eligible patients who will decide to participate in the study. Participants will also receive information sheets. Blood sample will be also obtained to assess HbA1c and eligible patients will be included in the study. It should be mentioned that ineligible patients will be excluded from the study after receiving nutrition recommendations for diabetes.

General information including age, parity, education, medical information, duration of the disease, etc. will be recorded through interviews at the beginning of the study. In order to obtain the physical activity level, metabolic equivalents will be calculated through a questionnaire at the beginning and the end of the study.52 To assess the dietary intakes, participants will be asked to complete a three-dietary record form (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day), one at the first week and another at the last week of the intervention; collected data will be analysed using Nutritionist IV software (The Hearst Corporation, San Bruno, California, USA). The questionnaires will be reviewed and approved by the ethical committee members. All the study related data will be stored confidentially.

Participants in the intervention group will take two capsules of resveratrol per day (one at breakfast and another at dinner) and individuals in the placebo group will take two capsules of 500 mg methylcellulose per day at the same time for 8 weeks; each capsule of resveratrol contains 500 mg of 99.71% micronized trans-resveratrol (particle size: <1.9 µm) which provides 495 mg trans-resveratrol without any inactive ingredients, fillers, additives or preservatives (Mega-Resveratrol, USA). Moreover, participants will continue taking diabetic medication prescribed by doctor during the study. Each bottle contains 60 capsules (providing supplement for 1 month). All participants will be requested to bring back the first bottle after first month and then they will be given the second bottle. At the end of the study, if the remaining capsules of every patient exceed 10% of the total administered capsules (12 capsules), that patient will be categorised as non-adherent. There will be some advices for enhancing the participant’s compliance such as taking capsules with meals. Moreover, patients who complete the intervention will have an 8-hour nutrition education programme for free. All randomised patients, including those who will complete the study or those who will not complete due to any reason, will follow the same schedule.

Any possible adverse event will be reported to the medical ethics committee within a week and Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences will be responsible for any participation-related problems. Some of the participants may withdraw from the study for any reason at any time before or after signing the consent form; the investigator may also terminate an individual’s participation in the study in order to keep the safety and protect the participant from excessive risks and/or to maintain the integrity of data due to the improper follow-up of the procedures by the participant.

Data collection

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric parameters will be taken at the beginning and end of the intervention by the same person. Height will be measured using a stadiometer (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) with an accuracy level of 0.5 cm; waist and hip circumferences will be measured to the nearest 0.5 cm according to the standard methods using a flexible tape.53 Weight estimate and body composition analysis (% fat mass, % fat free mass and visceral fat) will be performed via InBody (USA) analyser, with light clothing before and after the intervention. Body mass index will be calculated by dividing body weight (kg) by the height squared (m2); waist-to-hip ratio and waist–to-height ratio will be calculated via standard equations (6).

Biochemical measurements

After 12 hours of fasting, 10 mL of venous blood will be taken at baseline at week 8 of the study. A 6 mL of blood sample will be collected in the colt-activator tubes and centrifuged after 30 min clotting time (3000 g, 10 min at room temperature; Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) for serum isolation. Serum samples will be stored at −70°C until analyses. Remaining blood will be obtained in two ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-coated tubes for gene expression and HbA1c assessment separately. Biochemical analyses including fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-C and LDL-C will be measured using automated enzymatic methods and commercial kits (Pars Azmoon, Tehran, Iran). Laboratory kits will be used to assess circulating insulin levels and the percent of HbA1c will be assessed by ELISA (Monobind, California, United State) and high pressure liquid chromatography (Pars Azmoon, Tehran, Iran), respectively. Commercially available ELISA kits will be used for estimating serum levels of sCD163 and sTWEAK. Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) as an insulin sensitivity index and homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function (HOMA-B) as well as atherogenic index will be calculated using the suggested formulas.54 55 All laboratory data will be identified by an identification number to maintain the confidentiality of participants.

Gene expression assay

Total RNA will be extracted directly from whole blood using GeneAll Hybrid-R purification kit protocol (GeneAll Biotechnology Co., Seoul, South Korea). The quality and purity (260/280 nm ratio between 1.8 and 2.2) of the RNA will be checked using spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States). After normalisation, high-quality mRNA will be reverse transcribed to cDNA by cDNA synthesis kit (GeneAll Biotechnology Co.) and according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Three primer designing tools (Primer Blast, Oligocalc, and Gene runner 5.0.99) are applied for sequencing the study primers (table 1). Real-time PCR and SYBR Green method (Takara Bio Inc., Japan) will be applied to assess the mRNA expression levels of PPARα, p53, p21 and p16 in the StepOne system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). To this aim, 1 µL of cDNA, 10 µL of SYBR Green, 1 µL of primers (reverse and forward) and 0.4 µL of Rox will be mixed together. Final volume of solution will be reached to 20 µL by adding ddH2O (7/6 µL). Real-time PCR will be adjusted for initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 90°C for 15 s. The optimal annealing temperature for primers will be set at a range of 55°C–60°C for 20 s. The final step will be set up at 72°C for 20 s for primer extension. Glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) will be the housekeeping gene in real-time PCR assessments. Real-time PCR efficacy and changes in expression levels will be tested using LinRegPCR software56 and Pfaffl equation, respectively.57

Table 1.

Real-time PCR primer sequences

| Forward | Reverse | |

| p53 | GAGCTGAATGAGGCCTTGGA | CTGAGTCAGGCCCTTCTGTCTT |

| p21 | TGGAGACTCTCAGGGTCGAAA | GGCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGAAATC |

| p16 | CTTCCTGGACACGCTGGTG | GCATGGTTACTGCCTCTGGTG |

| PPARα | CTATCATTTGCTGTGGAGATCG | AAGATATCGTCCGGGTGGTT |

| GAPDH (Reference gene) | TGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTCATG | GCTTCACCACCTTCTTGATGTC |

GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha.

Statistical analysis

Principal researchers will have full access to the final data sets. Data entry and statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS for Windows V.23.0(SPSS). The intervention and the control arms will be compared with each other for primary analysis. One-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test will be conducted to check normal distribution of data. Continuous variable will be expressed as means±SD or median and IQR and categorical data will be presented as number and percentages in study groups. Independent sample t-test will be carried out for comparing parametric continuous data and Mann-Whitney U test will be used to test the differences in asymmetric variables between the two groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient will be applied to show the correlation between biochemical and anthropometric indices. General linear models will be used to assess the effects of resveratrol relative to placebo after adjustment for baseline values and participant’s characteristics. P value ≤0.05 will be defined as statistically significant for all tests.

Data analysis will be performed on two sets including the intention-to-treat (ITT) and the ‘per protocol’ analysis; ITT analysis considers all patients in the intervention or control groups as originally allocated by randomisation, independently of their actual adherence to the determined treatment and it ignores anything that happens after randomisation including misallocation, noncompliance, withdrawal or protocol deviations. In the case that researchers observe a significant difference between those individuals who will be allocated to receive the intervention and those individuals who will actually adhere to the intervention, additional analysis will be performed considering the actual adherence to the treatment (per protocol analysis). The results of the two mentioned analyses will be compared with each other.

Strengths and limitations

This study has been designed as a double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial, which will investigate the effects of resveratrol supplementation on the cellular factors associated with IH for the first time. It will also be the first to use high-bioavailable resveratrol supplement as a natural ligand for PPARα in human. However, as a limitation, the labelling of the containers as A and B can result in unblinding entire group when unblinding is necessary; although, resveratrol has not shown serious adverse events in previous studies. Another limitation in this study is the surrogate markers that will be used for endothelial function assessment instead of gold-standard methods such as flow-mediated dilation or peripheral arterial tonometry. Moreover, we will not perform oral glucose tolerance test or hyperinsulinaemic clamp to evaluate glycaemic control effects of resveratrol. Finally, this study is designed for short-term assessment of resveratrol supplementation effects in patients with T2DM.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public will not involve in the setting of the research question, outcome measures or study design and implementation. In this study, the intervention will involve taking daily supplement, and participants will not receive any lifestyle changes. So participants will not be asked to assess the benefits and burdens of participating. The summary results of the trial will be presented in a grouped form to scientific journals. Participants will be provided individual body composition report, as well as individual glycaemic and lipid profile results, on request, when study is completed.

Ethical consideration

Written consent form will be obtained from all patients before the study initiation. This study is registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript acknowledge Shahid Sadoughi university of medical sciences, Yazd Diabetes Research Center and Iran’s National Science Foundation (INSF).

Footnotes

Contributors: SA, AS-A, OT, MHS, MR and HM-K were involved in initial idea of this study and designing the trial. SA, AS-A and HM-K were contributed in writing the manuscript and getting grant. MT and EK-N are co-investigators and will involve in collecting data, concealment procedure and counselling patients. HF provided statistical expertise in clinical trial design, sample size calculation and blinding. MHS and EK-N were contributed to design of biochemical procedures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is a PhD thesis and is supported by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. This work is externally supported by INSF grant and was reviewed by their scientific committee before the funding was approved (grant no: 96010660).

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competinginterests.

Ethics approval: This protocol is approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (no: ir.ssu.sph.rec.1396.120).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Fowler MJ. Diabetes: Magnitude and mechanisms. Clinical Diabetes 2007;25:25–8. 10.2337/diaclin.25.1.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus—present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012;8:228–36. 10.1038/nrendo.2011.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, et al. . IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;94:311–21. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 2008;26:77–82. 10.2337/diaclin.26.2.77 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. . Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010;375:2215–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60484-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toupchian O, Sotoudeh G, Mansoori A, et al. . Effects of DHA-enriched fish oil on monocyte/macrophage activation marker sCD163, asymmetric dimethyl arginine, and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Lipidol 2016;10:798–807. 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polak JF, Pencina MJ, Pencina KM, et al. . Carotid-wall intima-media thickness and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2011;365:213–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1012592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dzau VJ, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Sedding DG. Vascular proliferation and atherosclerosis: new perspectives and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med 2002;8:1249–56. 10.1038/nm1102-1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Orr AW, Hastings NE, Blackman BR, et al. . Complex regulation and function of the inflammatory smooth muscle cell phenotype in atherosclerosis. J Vasc Res 2010;47:168–80. 10.1159/000250095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu H, Payne TJ, Mohanty DK. Effects of slow, sustained, and rate-tunable nitric oxide donors on human aortic smooth muscle cells proliferation. Chem Biol Drug Des 2011;78:527–34. 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01174.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. . ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 20112011;57:e215–e367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Z, Zhang X, Chen S, et al. . Lithium chloride inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration and alleviates injury-induced neointimal hyperplasia via induction of PGC-1α. PLoS One 2013;8:e55471 10.1371/journal.pone.0055471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Won KJ, Jung SH, Lee CK, et al. . DJ-1/park7 protects against neointimal formation via the inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Cardiovasc Res 2013;97:553–61. 10.1093/cvr/cvs363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gizard F, Amant C, Barbier O, et al. . PPARα inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation underlying intimal hyperplasia by inducing the tumor suppressor p16INK4a. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3228–38. 10.1172/JCI22756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gizard F, Nomiyama T, Zhao Y, et al. . The PPARalpha/p16INK4a pathway inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by repressing cell cycle-dependent telomerase activation. Circ Res 2008;103:1155–63. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature 1990;347:645–50. 10.1038/347645a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kota BP, Huang TH, Roufogalis BD. An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacol Res 2005;51:85–94. 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Role of the PPAR family of nuclear receptors in the regulation of metabolic and cardiovascular homeostasis: new approaches to therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005;5:177–83. 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toupchian O, Sotoudeh G, Mansoori A, et al. . Effects of DHA supplementation on vascular function, telomerase activity in PBMC, expression of inflammatory cytokines, and PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: study protocol for randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Med Iran 2016;54:410–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walworth NC. Cell-cycle checkpoint kinases: checking in on the cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000;12:697–704. 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00154-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang HS, Gavin M, Dahiya A, et al. . Exit from G1 and S phase of the cell cycle is regulated by repressor complexes containing HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF and Rb-hSWI/SNF. Cell 2000;101:79–89. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80625-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gizard F, Amant C, Barbier O, et al. . PPAR alpha inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation underlying intimal hyperplasia by inducing the tumor suppressor p16INK4a. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3228–38. 10.1172/JCI22756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Inoue H, Jiang XF, Katayama T, et al. . Brain protection by resveratrol and fenofibrate against stroke requires peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in mice. Neurosci Lett 2003;352:203–6. 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qin S, Lu Y, Rodrigues GA. Resveratrol protects RPE cells from sodium iodate by modulating PPARα and PPARδ. Exp Eye Res 2014;118:100–8. 10.1016/j.exer.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takizawa Y, Nakata R, Fukuhara K, et al. . The 4′-hydroxyl group of resveratrol is functionally important for direct activation of PPARα. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120865 10.1371/journal.pone.0120865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dong Z. Molecular mechanism of the chemopreventive effect of resveratrol. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2003;523-524:145–50. 10.1016/S0027-5107(02)00330-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. She QB, Bode AM, Ma WY, et al. . Resveratrol-induced activation of p53 and apoptosis is mediated by extracellular-signal-regulated protein kinases and p38 kinase. Cancer Res 2001;61:1604–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. . Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol 2008;6:e301 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cayrol C, Knibiehler M, Ducommun B. p21 binding to PCNA causes G1 and G2 cell cycle arrest in p53-deficient cells. Oncogene 1998;16:311–20. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rosso A, Balsamo A, Gambino R, et al. . p53 Mediates the accelerated onset of senescence of endothelial progenitor cells in diabetes. J Biol Chem 2006;281:4339–47. 10.1074/jbc.M509293200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guevara NV, Kim HS, Antonova EI, et al. . The absence of p53 accelerates atherosclerosis by increasing cell proliferation in vivo. Nat Med 1999;5:335–9. 10.1038/6585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanner FC, Yang ZY, Duckers E, et al. . Expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in vascular disease. Circ Res 1998;82:396–403. 10.1161/01.RES.82.3.396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang MW, Barr E, Lu MM, Mm L, et al. . Adenovirus-mediated over-expression of the cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat carotid artery model of balloon angioplasty. J Clin Invest 1995;96:2260–8. 10.1172/JCI118281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, et al. . Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001;280:E745–E751. 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chicheportiche Y, Bourdon PR, Xu H, et al. . TWEAK, a new secreted ligand in the tumor necrosis factor family that weakly induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1997;272:32401–10. 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Llauradó G, González-Clemente JM, Maymó-Masip E, et al. . Serum levels of TWEAK and scavenger receptor CD163 in type 1 diabetes mellitus: relationship with cardiovascular risk factors. a case-control study. PLoS One 2012;7:e43919 10.1371/journal.pone.0043919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kralisch S, Ziegelmeier M, Bachmann A, et al. . Serum levels of the atherosclerosis biomarker sTWEAK are decreased in type 2 diabetes and end-stage renal disease. Atherosclerosis 2008;199:440–4. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Díaz-López A, Chacón MR, Bulló M, et al. . Serum sTWEAK concentrations and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in a high cardiovascular risk population: a nested case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:3482–90. 10.1210/jc.2013-1848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiley SR, Winkles JA. TWEAK, a member of the TNF superfamily, is a multifunctional cytokine that binds the TweakR/Fn14 receptor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2003;14:241–9. 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Levy AP, Moreno PR. Intraplaque hemorrhage. Curr Mol Med 2006;6:479–88. 10.2174/156652406778018626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, et al. . Atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability to rupture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:2054–61. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000178991.71605.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kockx MM, Cromheeke KM, Knaapen MW, et al. . Phagocytosis and macrophage activation associated with hemorrhagic microvessels in human atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:440–6. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000057807.28754.7F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh N, Moody AR, Gladstone DJ, et al. . Moderate carotid artery stenosis: MR imaging-depicted intraplaque hemorrhage predicts risk of cerebrovascular ischemic events in asymptomatic men. Radiology 2009;252:502–8. 10.1148/radiol.2522080792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, et al. . Association between carotid plaque characteristics and subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular events. Stroke 2006;37:818–23. 10.1161/01.STR.0000204638.91099.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fabriek BO, Dijkstra CD, van den Berg TK. The macrophage scavenger receptor CD163. Immunobiology 2005;210:153–60. 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bover LC, Cardó-Vila M, Kuniyasu A, et al. . A previously unrecognized protein-protein interaction between TWEAK and CD163: potential biological implications. J Immunol 2007;178:8183–94. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Urbonaviciene G, Martin-Ventura JL, Lindholt JS, et al. . Impact of soluble TWEAK and CD163/TWEAK ratio on long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Atherosclerosis 2011;219:892–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moreno JA, Dejouvencel T, Labreuche J, et al. . Peripheral artery disease is associated with a high CD163/TWEAK plasma ratio. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010;30:1253–62. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.203364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leiro J, Alvarez E, Arranz JA, et al. . Effects of cis-resveratrol on inflammatory murine macrophages: antioxidant activity and down-regulation of inflammatory genes. J Leukoc Biol 2004;75:1156–65. 10.1189/jlb.1103561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. D’Amore S, Vacca M, Graziano G, et al. . Nuclear receptors expression chart in peripheral blood mononuclear cells identifies patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1832:2289–301. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kirby A, Gebski V, Keech AC. Determining the sample size in a clinical trial. Med J Aust 2002;177:256–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aadahl M, Jørgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1196–202. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074446.02192.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Control CfD, Prevention. Anthropometry procedures manual. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mirmiran P, Bahadoran Z, Golzarand M, et al. . Ardeh (Sesamum indicum) could improve serum triglycerides and atherogenic lipid parameters in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Iran Med 2013;16:652 doi:0131611/AIM.008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Motamed N, Miresmail SJ, Rabiee B, et al. . Optimal cutoff points for HOMA-IR and QUICKI in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A population based study. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30:269–74. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Robledo D, Hernández-Urcera J, Cal RM, et al. . Analysis of qPCR reference gene stability determination methods and a practical approach for efficiency calculation on a turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) gonad dataset. BMC Genomics 2014;15:648 10.1186/1471-2164-15-648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic acids research 2001;29(9:e45–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.