Abstract

Introduction

Hospital redevelopment projects typically intend to improve hospital functioning and modernise the delivery of care. There is research support for the proposition that redevelopment along evidence-based design principles can lead to improved quality and safety. However, it is not clear how redevelopment influences the wider context of the hospital and its functioning. That is, beyond a limited examination of intended outcomes (eg, improved patient satisfaction), are there additional consequences (positive, negative or unintended) occurring within the hospital after the physical environment is changed? Is new always better? The primary purpose of this study is to explore the ripple effects of how hospital redevelopment may influence the organisation, staff and patients in both intended and unintended ways.

Methods and analysis

We propose to conduct a longitudinal, mixed-methods, case study of a large metropolitan hospital in Australia. The study design consists of a series of measurements over time that are interrupted by the natural intervention of a hospital redevelopment. How hospital redevelopment influences the wider context of the hospital will be assessed in six domains: expectations and reflections of hospital redevelopment, organisational culture, staff interactions, staff well-being, efficiency of care delivery and patient experience. Methods of data collection include a hospital-wide staff survey, semistructured interviews, a network survey, a patient experience survey, analysis of routinely collected hospital data and observations. In addition to a hospital-level analysis, a total of four wards will be examined in-depth, with two acting as controls. Data will be analysed using thematic, statistical and network analyses, respectively, for the qualitative, quantitative and relational data.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been reviewed and approved by the relevant Ethics Committee in New South Wales, Australia. The results will be actively disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and in report format to the stakeholders.

Keywords: quality in health care, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first of its kind to explore how hospital redevelopment may influence the organisation, staff and patients in both intended and unintended ways.

The project design, including the development of tools, was conducted in collaboration with the hospital under investigation.

A key strength of the study is the use of mixed-methods and multiple time points of data collection.

A limitation of the study is that findings may be specific to the hospital and the wards under investigation.

Background

Healthcare systems worldwide are facing significant challenges to their long-term sustainability and the delivery of safe, effective, quality care.1–3 Ageing populations, increasing costs of medical advances, issues with health workforce retention, outdated and inadequate infrastructure, concerns about the quality and safety of health services, and wasteful spending are some of the many challenges facing contemporary healthcare systems.1 4 5 For hospitals, as healthcare institutions providing in-patient treatment 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, one of their major challenges lies with ageing populations and overall population growth. Indeed, hospitals worldwide are experiencing a higher incidence of elderly people with greater demand for hospital services and hospital beds.4 6 One way to respond to this challenge is through hospital expansion, redevelopment and modernisation.

The redevelopment of hospitals in high-income countries appears to be increasingly common,7 8 for several reasons. First, hospitals must evolve and adapt to match the changing healthcare needs of the communities they service.9 Hospitals everywhere are challenged to meet the demands of ageing populations and overall population growth; expansion through hospital redevelopment is a way to resolve consequent issues such as inadequate infrastructure. Second, hospitals must adapt to changing trends and technological advances in medicine. For example, the use of mechanical lifters at the bedside,10 or point-of-care testing,11 may require reconfiguration of beds in the ward. Third, hospital redevelopment may take place when existing infrastructure is found to compromise staff safety or infection control for patients. For example, the redevelopment of operating theatres to include laminar flow was a deliberate strategy aimed at reducing infection rates.12 Another reason for hospital redevelopment lies in the well-documented association between an aesthetically appealing hospital environment and positive outcomes.13–16 To this end, stakeholders may make design decisions on the basis of evidence, to improve not only the physical appearance, but the functioning of the hospital, including improved quality of care, patient and staff satisfaction and financial savings.13

While the literature suggests that redevelopment projects and the implementation of new design features in hospitals are associated with improved outcomes for staff, patients and the broader organisation,17 these outcomes have mainly been addressed in a linear frame. This means hospital redevelopment has typically been assessed by evaluating how one feature (eg, a new garden) impacts one intended outcome (eg, satisfaction), rather than exploring possible unintended consequences of changing the hospital system. Further, there has been a focus on physical change, rather than the behavioural, cultural or social shifts characteristic of organisational change.18 As the physical environment of the hospital is altered, other social processes may be unintentionally influenced, for example, roles, responsibilities, culture and the way staff work together. Indeed, past research has revealed that the behaviours and social interactions of staff are influenced by the physical healthcare environment. This was shown for formal teamwork and communication19 as well as informal communication patterns such as support and socialisation.20 21 An example of a ripple effect is that beneficial working relationships between adjacent units may be disrupted if they move apart, possibly leading to poorer quality of patient care. This suggests that there is a need for a more indepth examination of the potential ripple effects of a hospital redevelopment, beyond the physical changes.

This is particularly important given how interconnected and complex hospital systems are.22 23 Healthcare and healthcare organisations have been described as complex adaptive systems, characterised by non-linear and often unpredictable processes.24 25 In introducing a potentially large long-term change (and short-term disruption) as hospital redevelopment into a complex interconnected system, this perspective highlights that we need to look beyond just the intended or desired outcomes of hospital redevelopment. In taking a complex systems perspective to examine how redevelopment may influence the hospital, we recognise that we cannot isolate single factors (eg, patient satisfaction). Rather, we need to consider the influence on many complex and interconnected levels and agents of the hospital system.17 This perspective aligns with recent moves to reappraise change management theory—to one that no longer perceives organisational change as planned, uniform and predictable, but an emergent process in a multilayered, complex ecosystem that is driven as much from the bottom up as the top down.26

Therefore, rather than assuming that the redevelopment of hospitals will only lead to a particular intended outcome, we argue there is a need to consider the unintended ripple effects and widespread influences of introducing an organisational change into this complex system. Based on these issues, we pose the question: is new always better? Beyond the targeted outcome of improving the physical infrastructure, do we really know what happens within the hospital after the physical environment is comprehensively changed?

Methods and analysis

Study aim

The present research aims to explore how hospital redevelopment influences the wider context of the hospital and its functioning. In particular, the study will explore how hospital redevelopment may influence the organisation, staff and patients in both intended and unintended ways.

Study design

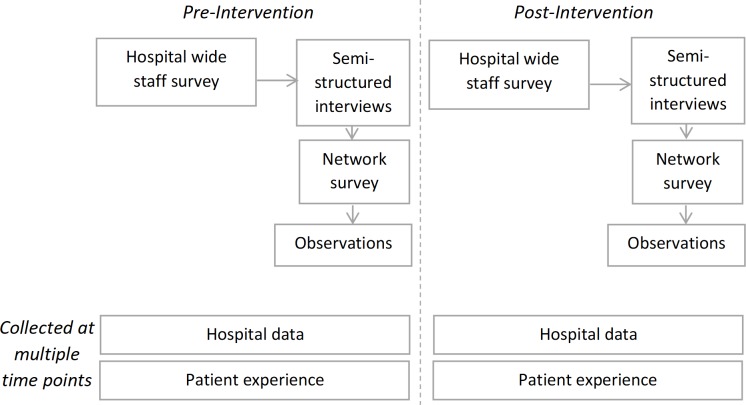

We propose to conduct a pragmatic, longitudinal, mixed-methods case study of a large metropolitan hospital in Australia. As illustrated in figure 1, the design is a mixture of pre–post data collection points and a series of measurements over time that are interrupted by the natural intervention of the hospital redevelopment (ie, interrupted time series (ITS) data). ITS is a quasi-experimental method for assessing routinely collected data over evenly spaced out intervals to assess the impact of change.27 The combination of these methods of data collection allows for a rich and dynamic exploration of how hospital redevelopment influences the organisation, staff and patients, in intended and unintended ways.

Figure 1.

Data collection points over time.

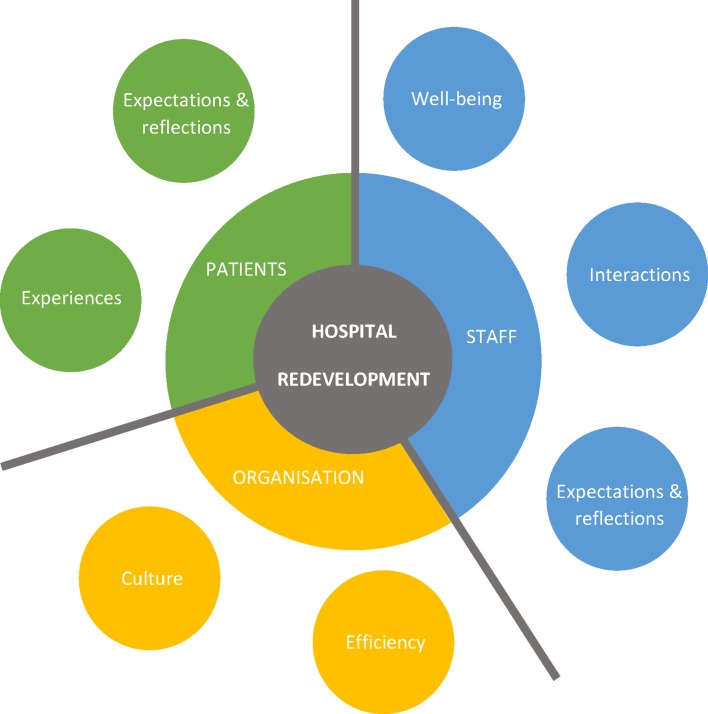

How hospital redevelopment influences the wider context of the hospital will be assessed at three levels: organisation, staff and patients; and six domains: expectations and reflections, organisational culture (ie, shared beliefs and attitudes), staff interactions, staff well-being, efficiency of care delivery and patient experience (figure 2). These domains are underpinned by considerations of key literature13 14 and will be captured by six methods of data collection: hospital-wide staff survey, semistructured interviews, network survey, patient experience survey, analysis of routinely collected hospital data and observations (table 1). Of these six methods, two (hospital data and patient experience) will be assessed at a minimum of six observations points. The other four methods of data collection will be assessed at two time points, pre- and post- the intervention of hospital redevelopment. Data collection, particularly for interviews, network survey and observations, will occur in a sequential manner (eg, design of the network survey depends on the analysis of interview data).

Figure 2.

Domains to be assessed.

Table 1.

Domains to be assessed and corresponding methods

| Method | Domains | |||||

| Expectations and reflections | Organisational culture | Staff interactions | Staff well-being | Efficiency | Patient experience | |

| Hospital-wide staff survey | x | x | ||||

| Semistructured interviews | x | x | x | |||

| Network survey | x | x | x | x | ||

| Patient experience survey* | x | x | ||||

| Hospital data* | x | x | ||||

| Observations | x | x | ||||

* Data captured at multiple time points; all other methods are captured at two-time points, preintervention and postintervention.

Study setting

The project will be conducted at a public, metropolitan hospital in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The hospital has between 200 and 500 beds, and is currently undergoing a multimillion-dollar development to meet the growing needs of the community. The redevelopment will see the opening of a new acute services building, the relocation of several wards to this new building, increases in resources (equipment, staffing) and the adoption of new approaches: new ways of working and new e-medical systems of care delivery. These changes are set to be in place by mid-2019. This study includes both a broad analysis of hospital-level data and an in-depth analysis of four specific wards; two wards moving into the new building during the redevelopment project (maternity and intensive care unit), one ward not being moved into the new building but remaining in its current location (surgical) and one ward that was moved to a new building two years prior (respiratory). In essence, the wards moving are the intervention wards and those not moving act as controls. Chosen wards were equivalent in bed, and staff numbers. Although these wards differ somewhat in the type of care delivered, they are deemed to be sufficiently homogeneous; they were chosen in discussion with hospital executives, to cover wards undergoing and not undergoing redevelopment during the study.

Study procedures

Routinely collected hospital data

Routinely collected hospital data, such as throughput rates and bed occupancy, will be made accessible to the research team. This hospital data will be used to explore efficiency as an indicator of change at the hospital and ward levels and make inferences about how hospital redevelopment influences the efficiency of care delivery. These data will be captured at equal monthly intervals, forming part of the ITS analysis.

Patient experience survey

Patient experience data will be captured using a hospital platform already in place. At present, the hospital under investigation has an online survey platform to collect patient experience data, which can be analysed on the ward level. The present project will tap into this platform in order to explore how hospital redevelopment influences patient experience. The questions asked are routinely collected and used to examine overall experience of hospital care. The survey will include the previously validated short form Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire-15 (PPE-15) for measuring patients' experience of in-patient care. PPE-15 measures patients’ subjective experience of care during their hospital stay.28 These survey data will be collected at multiple time points, for ITS analysis.

Hospital-wide staff survey

In NSW, Australia, employees working in the public sector, including public hospitals, are invited to participate in the ‘People Matter Employee Survey’; a validated survey where employees can express their views and experiences in their workplace.29 Survey findings are demarcated by agency, such as by each hospital in the NSW public sector (including the hospital under investigation). The survey is distributed and completed annually over a 1 month period. The response rate of the last annual survey for this hospital was 39%, slightly higher than the relevant local health district and an increase over previous years. Survey responses will be made accessible to the research team in aggregated, unidentifiable form. These data will be analysed and used to understand the changes in attitudes and experiences of all hospital staff, at two timepoints, pre- and post- the redevelopment.

Semistructured interviews

Semistructured interviews were chosen because they enable an in-depth understanding of a new area with little previous research.30 The purpose of the interviews before the intervention will be to collect information on: (1) a detailed understanding of the hospital’s culture and current ways of working, (2) the expectations of hospital staff regarding how the ongoing hospital redevelopment might influence their work, (3) any uncertainties they had about the hospital redevelopment project and (4) staff predictions of how ways of working with other staff might change in light of the redevelopment. The questions for the interviews taking place after the intervention will be similar, but with a focus on reflections on the change, and perceptions of how the hospital redevelopment may have influenced them personally, other staff, culture and ways of working together. Participants eligible for inclusion in the interviews will be all staff working on the four wards under investigation, either part-time or full-time. By all staff we mean clinicians, administrative, managerial and domestic staff. By collecting diverse staff perspectives, we can shed light on how different types and levels of hospital staff may be influenced by the redevelopment. The number of interview participants will be ~40 (at each time point), with a minimum of 10 participants per ward or until data saturation is reached. Semistructured interviews will be conducted by the first author in private settings at the participants’ place of work (in ward interview rooms or private offices). At times where participants are unable to meet the researcher in person, interviews will be conducted over the phone in similar private settings. Findings from these interviews will be used to develop the subsequent network survey and observational component of the research.

Network survey

Surveys are a common tool of data collection used to understand the attitudes and perceptions of professionals working in health services31; in this case, all types of staff working in the hospital under redevelopment. Questions in this survey will be partly dependent on the analysis of interview data.

Part 1: demographics and other factors

The first part of the survey will be used to collect demographic data and expectations and reflections on the hospital redevelopment project. Existing validated measures will be used to examine organisational culture,32 measures of staff well-being (such as job satisfaction,33 burnout,34 intention to leave35) and readiness for organisational change.36 The same set of questions will be used pre- and post- the intervention.

Part 2: social network survey

Part 2 of the survey will consist of a social network survey. Social network research involves the investigation of social structures such as collaboration, through the use of networks and graph theory.37 This provides a basis to investigate a range of collaborative issues, including silo-working and bottlenecks in communication flow,38 in order to explore how hospital redevelopment influences patterns of staff interaction. The collection of network data to assess interactions is an established tool38 used in previous healthcare research.39 40 In this part of the survey, staff will be asked to report which staff members they work with most closely. Given the sequential nature of the study design, the exact wording of the network questions is dependent on the interview findings. The survey will be similar after the intervention, with the exception of additional open-ended questions asking how patterns of interaction may have changed in response to the hospital redevelopment project.

Observations

Generally speaking, observational data will be used to provide a rich description of how hospital redevelopment influences the ways staff work together. Observational data collection will be complementary to the quantitative data of the network survey and will add explanatory value to understanding how the hospital system may change and evolve over time in response to redevelopment. Using observations in conjunction with social network research, as well as in healthcare research more broadly, helps illuminate taken-for-granted and unintended aspects of collaboration that may not be disclosed in surveys or other forms of data collection.41 Observations will also provide rich data relating to the culture on the wards and how it might be influenced by redevelopment, which is otherwise difficult to capture in self-report questionnaires. The observations will include all types of hospital staff (clinical and non-clinical). Given the sequential nature of this study, specific observational methods will be designed based on interview and survey findings.

Data analyses

Interview and observational data will be analysed using the qualitative method of thematic analysis,42 using an open coding process.43 Data collection and analysis will occur iteratively; questions used for interviews and guides for observations will be continuously refined and expanded in light of emerging findings. Qualitative data will be analysed using NVivo V.11.4, for coding and qualitative data analysis.

For quantitative analysis, demographic and descriptive data (eg, staff well-being, organisational culture) collected from the network survey, will be analysed using SPSS Statistics V.22.0. Relational data from the network survey will be graphically presented using Gephi V.0.9.2 software, and analysed using stochastic actor-based models.44 These social network analysis techniques include the analysis of endogenous (structural, network self-organisation) and exogenous (individual characteristics) variables. Trends in time series data will be graphically presented using line graphs, and statistically analysed using segmented regression analysis on SPSS.

Integrating results

Qualitative, quantitative and network results from the diverse data collection methods will be integrated to form an overall picture of ways hospital redevelopment influences the organisation, staff and patients in both intended and unintended ways. Data will be synthesised using a mixed-methods matrix45; a way to triangulate data and display findings emerging from each level (patient, staff, organisational) and the various methods of data collection. The matrix will delineate data for the intervention and control wards to allow for comparison. Data will be categorised as positive, negative or neutral, prehospital and posthospital redevelopment. The nature of influence will be classified as either intended or unintended (eg, intended that patient satisfaction will increase). Classification of what changes were intended or unintended will be deduced in consultation with key stakeholders at the hospital. This will be followed by consideration of where there is agreement, partial agreement, silence or dissonance between findings from different methods on different levels.45

Patient and public involvement

The institute consults with patients, their representatives and the general public regularly to ensure that adequate input is secured for research projects and programmes of research. A key partner is the Consumers Health Forum of Australia. Patients were not directly involved in the development of the research question, study design, recruitment or conduct of this study. However, the staged nature of the study design means that concerns raised by patients in the survey before the intervention can be used to refine research questions and methods to assess the effects of hospital redevelopment once the move into the new hospital building takes place. At the end of the study, final results will be disseminated broadly to patients and the wider public.

Discussion

This study seeks to explore a significant gap in the literature, namely, how redevelopment influences the wider context of the hospital and its functioning. This research is timely as hospital redevelopment projects are ubiquitous and on the rise.7 8 The exploratory nature of this case study enables the identification of unintended influences, positive or negative, that come from conducting a redevelopment project in the hospital physical environment. The study looks at social, behavioural and cultural changes that may come as a result of the physical change (eg, teamwork and culture). If unintended consequences of hospital redevelopment on the organisation, staff and patients are revealed, then we may be able to delineate and propose ways to deal with these factors. These findings may be used to guide policies on how to implement major hospital redevelopment projects with minimal disruption and awareness of the intended and unintended effects of this large change.

As to limitations, the findings may not be generalisable to all instances of hospital redevelopment and may be specific to the four wards and one hospital examined in this study. They were purposively chosen rather than randomised. While findings may not be generalisable, the qualitative test is credibility and the protocol has been designed to optimise research credibility at each point. This in-depth case study provides the opportunity to uncover theoretical insights into the processes of change in the healthcare system and how such processes can impact staff, patients and the organisation. Another potential limitation lies in the two-time point data collection for four of the six methods of this study. Detected changes assessed by these methods can, in some instances, be affected by numerous other factors, such as, seasonal, autocorrelational and non-stationary biases often found in two-time point longitudinal data.27 In including ITS data and control wards, this limitation will be addressed as such biases can be identified when there are numerous time points and varied contexts. Therefore, the combination of pre–post and ITS data collection along with multilevel analysis of the complex hospital system is beneficial in the exploration of unintended influences to answer the question: is new always better?

Ethics and dissemination

There are no known health or safety risks associated with participation in any aspect of the described study. The results will be actively disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and in report format to the stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CP, JB and BG conceptualised the study. CP drafted the initial manuscript, assisted by KC, JL and LAE. All authors contributed to the refinement of the final manuscript.

Funding: CP was funded by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) PhD Scholarship. JB is supported by multiple grants, including the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Grant for Health Systems Sustainability (ID: 9100002).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braithwaite J, Mannion R, Matsuyama Y, et al. ; Health systems improvement across the globe: success stories from 60 countries. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braithwaite J, Matsuyama Y, Johnson J. Healthcare reform, quality and safety: perspectives, participants, partnerships and prospects in 30 countries. Surrey, UK: CRC Press, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morris M. Global health care outlook: battling costs while improving care: Deloitte, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braithwaite J, Mannion R, Matsuyama Y, et al. . Healthcare systems: future predictions for global care. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armstrong BK, Gillespie JA, Leeder SR, et al. . Challenges in health and health care for Australia. Med J Aust 2007;187:485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ritchie E. NSW budget 2017: ‘hospital building boom’ at heart of $23bn deal. The Australian 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carpenter D, Hoppszallern S. 2006 hospital building report. The boom goes on. Hosp Health Netw 2006;80:48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McKee M, Healy J. The role of the hospital in a changing environment. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:803–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. SANDOZ. Changing societies, changing healthcare needs: three demographic trends shaping the future of medical services Sandoz International GmbH. 2017. https://www.sandoz.com/stories/system-capacity-building/changing-societies-and-healthcare-needs-three-demographic-trends

- 11. Junker R, Schlebusch H, Luppa PB. Point-of-care testing in hospitals and primary care. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010;107:561 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McHugh SM, Hill AD, Humphreys H. Laminar airflow and the prevention of surgical site infection. More harm than good? Surgeon 2015;13:52–8. 10.1016/j.surge.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joseph A, Kirk Hamilton D. The Pebble Projects: coordinated evidence-based case studies. Building Research & Information 2008;36:129–45. 10.1080/09613210701652344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. . A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD 2008;1:61–125. 10.1177/193758670800100306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schweitzer M, Gilpin L, Frampton S. Healing spaces: elements of environmental design that make an impact on health. J Altern Complement Med 2004;10(Suppl 1):S-71–70. 10.1089/acm.2004.10.S-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rechel B, Buchan J, McKee M. The impact of health facilities on healthcare workers' well-being and performance. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:1025–34. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ulrich R, Zimring C, Quan X, et al. . The role of the physical environment in the hospital of the 21st century: A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Concord, CA 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burnes B. Managing change: a strategic approach to organisational dynamics. 4th edn: Prentice Hall, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gharaveis A, Hamilton DK, Pati D. The impact of environmental design on teamwork and communication in healthcare facilities: a systematic literature review. HERD 2018;11:119–37. 10.1177/1937586717730333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Becker F. Nursing unit design and communication patterns: what is "real" work? HERD 2007;1:58–62. 10.1177/193758670700100115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naccarella L, Raggatt M, Redley B. The influence of spatial design on team communication in hospital emergency departments. HERD 2019;12 10.1177/1937586718800481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braithwaite J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ 2018;361:k2014 10.1136/bmj.k2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, et al. . When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med 2018;16:63 10.1186/s12916-018-1057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Ellis LA, et al. . Complexity science in healthcare-aspirations, approaches, applications and accomplishments: a white paper. Sydney, Australia: Macquarie University, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001;323:625–8. 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Todnem By R. Organisational change management: A critical review. J Change Manag 2005;5:369–80. 10.1080/14697010500359250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lagarde M. How to do (or not to do)… Assessing the impact of a policy change with routine longitudinal data. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:76–83. 10.1093/heapol/czr004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care 2002;14:353–8. 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. NSW Government. People Matter Employee Survey. 2018. https://www.psc.nsw.gov.au/reports-data/state-of-the-sector/people-matter-employee-survey

- 30. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: a review of survey instruments. Med Care 2015;53:e16–e30. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827feef6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. . The safety attitudes questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:44 10.1186/1472-6963-6-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bowling NA, Hammond GD. A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. J Vocat Behav 2008;73:63–77. 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981;2:99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stone PW, Larson EL, Mooney-Kane C, et al. . Organizational climate and intensive care unit nurses' intention to leave. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1907–12. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218411.53557.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Holt DT, Armenakis AA, Feild HS, et al. . Readiness for organizational change: the systematic development of a scale. J App Behav Sci 2007;43:232–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robins G. Doing social network research: network-based research design for social scientists: Sage Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38. :–.Long JC, Bishop S. Social network research Liamputtong P, Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer, 2018:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Long JC, Cunningham FC, Wiley J, et al. . Leadership in complex networks: the importance of network position and strategic action in a translational cancer research network. Implement Sci 2013;8:122 10.1186/1748-5908-8-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan B, Reeve E, Matthews S, et al. . Medicine information exchange networks among healthcare professionals and prescribing in geriatric medicine wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017;83:1185–96. 10.1111/bcp.13222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lingo EL, O’Mahony S. Nexus work: brokerage on creative projects. Adm Sci Q 2010;55:47–81. 10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Newell R, Burnard P. A pragmatic approach to qualitative data analysis : Newell R, Burnard P, Research for evidence-based practice in healthcare. 2nd ed Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lusher D, Koskinen J, Robins G. Exponential random graph models for social networks: theory, methods, and applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010;341:c4587 10.1136/bmj.c4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.