Abstract

Objectives

In an acute heart failure (AHF) setting, proenkephalin A 119–159 (penKid) has emerged as a promising prognostic marker for predicting worsening renal function (WRF), while bioactive adrenomedullin (bio-ADM) has been proposed as a potential marker for congestion. We examined the diagnostic value of bio-ADM in congestion and penKid in WRF and investigated the prognostic value of bio-ADM and penKid regarding mortality, rehospitalisation and length of hospital stay in two separate European AHF cohorts.

Methods

Bio-ADM and penKid were measured in 530 subjects hospitalised for AHF in two cohorts: Swedish HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial (HARVEST-Malmö) (n=322, 30.1% female; mean age 75.1+11.1 years; 12 months follow-up) and Italian GREAT Network Rome study (n=208, 54.8% female; mean age 78.5+9.9 years; no follow-up available).

Results

PenKid was associated with WRF (area under the curve (AUC) 0.65, p<0.001). In multivariable logistic regression analysis of the pooled cohort, penKid showed an independent association with WRF (adjusted OR (aOR) 1.74, p=0.004). Bio-ADM was associated with peripheral oedema (AUC 0.71, p<0.001), which proved to be independent after adjustment (aOR 2.30, p<0.001). PenKid was predictive of in-hospital mortality (OR 2.24, p<0.001). In HARVEST-Malmö, both penKid and bio-ADM were predictive of 1-year mortality (aOR 1.34, p=0.038 and aOR 1.39, p=0.030). Furthermore, bio-ADM was associated with rehospitalisation (aOR 1.25, p=0.007) and length of hospital stay (β=0.702, p=0.005).

Conclusion

In two different European AHF cohorts, bio-ADM and penKid perform as suitable biomarkers for early detection of congestion severity and WRF occurrence, respectively, and are associated with pertinent clinical outcomes.

Keywords: bioactive adrenomedullin, proenkephalin, acute heart failure, congestion, worsening renal function

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

In an acute heart failure setting, proenkephalin A 119–159 (penKid) has emerged as a promising prognostic marker for predicting worsening renal function with much faster reactivity time then creatinine, while bioactive adrenomedullin (bio-ADM) has been proposed as a potential marker for assessment of residual congestion.

What does this study add?

This study substantiates the scarce knowledge about both bio-ADM and penkid and identifies two novel biomarkers for congestion assessment and kidney function. Congestion assessed by bio-ADM was associated with longer hospital stay and higher risk of rehospitalisation. penkid was associated with worsening renal function and higher risk of both in-hospital and postdischarge mortality.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Bio-ADM might help identify subjects with residual congestion, who could benefit from intensified diuretic therapy. penKid, with its fast rise when kidneys are damaged, could help identify patients who do not tolerate the intensified diuretic therapy, faster than creatinine.

Introduction

The cardiorenal syndrome can generally be defined as a pathophysiological disorder of the heart and kidneys, where acute or chronic dysfunction in one organ may induce acute or chronic dysfunction in the other organ.1 Worsening renal function (WRF) and neurohormonal activation are important contributors to fluid retention and acute decompensation in heart failure. The use of biomarkers might help to differentiate between different phenotypes in acute heart failure (AHF) with different outcomes and optimal treatment strategies. Biomarkers reflecting haemodynamic stress/systolic dysfunction are the B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP/N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP)), which are often used to follow the progression of heart failure.2 However, their prognostic value in predicting death in AHF is suboptimal.3 Also, high baseline values of BNP in patients with AHF have not shown any association with clinical signs of congestion,4 5 and NT-proBNP-guided therapy was recently shown not to significantly improve time to first hospitalisation or cardiovascular mortality.6

A biomarker reflecting renal status, Cystatin C, has been found to predict clinical outcomes in patients with AHF with greater accuracy than creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and blood urea nitrogen. However, these results derive mostly from patients with apparently preserved renal function and may not be applicable to patients with heart failure with concomitant renal dysfunction.3 Consequently, new biomarkers are called on for an improved cardiorenal risk stratification of patients with AHF.

Bioactive adrenomedullin (bio-ADM) is a vasoactive peptide hormone and a protective factor of vascular integrity.7 A new immunoassay especially developed to measure bio-ADM8 was recently used in a study suggesting bio-ADM as a marker of congestion in AHF.9 Furthermore, bio-ADM has been shown to be associated with adverse events within 30 days after hospitalisation for AHF.10

Enkephalin peptides exert cardiodepressive effects.11 One of those is proenkephalin A 119–159 (penKid, also described as PENK), freely filtered through the glomerulus.12 In chronic heart failure, higher penKid concentrations were found to be associated with lower GFR and renal blood flow.13 PenKid has also been shown to predict adverse clinical outcomes in acute myocardial infarction14 and AHF.15 Thus, the possibility to adequately assess congestion together with real time renal function could be of significant value in the prediction and prevention of the cardiorenal syndrome and ultimately improving patient care.

In the present study, taking advantage of two separate AHF cohorts from Sweden and Italy, we examined the association between bio-ADM and clinical signs of congestion and the relationship between penKid and WRF. Furthermore, we assessed the possible impact of bio-ADM and penKid related to worsening of prognosis for each biomarker separately.

Methods

HARVEST-Malmö

The HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial (HARVEST-Malmö)16 is an ongoing study in Malmö, Sweden, with the sole inclusion criteria being admitted to a cardiology or internal medicine ward for treatment of heart failure regardless of the aetiology, duration or severity. Between March 2014 and August 2018, 324 consecutive patients admitted to cardiology or internal medicine wards under the diagnosis of either new onset or worsening chronic congestive heart failure were enrolled. Inability to consent to the study was the only exclusion criteria. For patients with severe cognitive impairment, defined as mini mental test examination score <13 points, the relatives are instead being informed and asked for permission for the patient’s behalf. The study was complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

GREAT Network Rome

Between May 2013 and March 2015, 245 patients that were referred to the emergency department of Sant’Andrea hospital complaining of heart failure symptoms and signs and who received a final diagnosis of new onset or worsening chronic congestive heart failure were enrolled to the GREAT Network Acute Heart Failure Rome Study, with inability to consent to the study as the only exclusion criteria. The study protocol was complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical examination

In both cohorts, the examination included a clinical examination, blood sample donations and blood pressure measurements at admission. Diabetes was defined as either self-reported physician diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes, or use of antidiabetic medication or fasting plasma glucose ≥7 mmol/L. Prior heart failure was defined as either prior hospitalisation for heart failure or a heart failure diagnosis prior to inclusion in the study.

Laboratory assays

All laboratory assays are described in the online Supplemental Material.

openhrt-2019-001048supp001.docx (20.4KB, docx)

Outcomes

In both cohorts, patients were examined for signs of congestion (dyspnoea, oedema, signs of congestion on X-ray and auscultatory lung rales). Further, a clinical congestion score (CCS) was calculated by summing the individual scores for each sign of congestion. A score from 0 to 4 points was attributed to each patient.

WRF was defined as an increase of plasma creatinine of >26.5 μmol/L or 0.3 mg/dL or 50% higher than the admission value within 48 hours of admission.15 17 In-hospital mortality was defined as all-cause mortality during the hospital stay in both cohorts. For HARVEST-Malmö, where we had follow-up data, 1-year mortality was defined as all-cause mortality within 1 year from study inclusion and obtained from Swedish total population register Statistics Sweden.

Rehospitalisation (available in HARVEST-Malmö only) was defined as the first of any unplanned readmissions for worsening heart failure until 2 July 2018 and was obtained through regional administrative patient registries.

Statistics

In both cohorts, variables with non-normal distribution (bio-ADM and penKid) were log-transformed and normalised (using z-score transformation) prior to analyses. Since different assays were used for natriuretic peptides, the data from both cohorts were log transformed and then normalised (using z-score transformation) prior to pooling of the natriuretic peptide data. For all analyses, subjects with missing data on any of the covariates were excluded.

The area under the curve (AUC) of bio-ADM for peripheral oedema, in-hospital mortality, 1-year mortality and rehospitalisation was calculated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. As for penKid, AUC was calculated for WRF and in-hospital mortality. The cross-sectional associations of bio-ADM with each of the four signs of congestion, as well as bio-ADM with CCS, were explored using logistic regression models.

Correlations between penKid and creatinine on admission were explored using Spearman’s correlation test. The cross-sectional associations of penKid and WRF were explored using two logistic regression models: crude (univariable) and in the pooled cohort adjusted for diabetes, systolic blood pressure (SBP), ACE inhibitor (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers, prior heart failure, creatinine and BNP, all previously associated with WRF (multivariable). The cross-sectional associations of bio-ADM and penKid with in-hospital mortality were explored using univariable and bivariable logistic regression models due to the low event rate (24 events in the pooled cohort).

In HARVEST-Malmö, additional analyses were carried out for 1-year mortality and rehospitalisation at follow-up, using Cox regression models. In analyses of rehospitalisation, subjects that deceased during hospital stay were excluded from the model prior to analysis. Analyses of length of hospital stay were obtained using linear regression models.

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.25 and a two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Detailed characteristics of the study populations are presented in table 1. Number of events for peripheral oedema and WRF within low and high levels of bio-ADM and penKid are presented in the online supplementary table 1, where low and high levels are defined based on previous descriptions in literature.8 12

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the HARVEST-Malmö cohort, the GREAT Network Rome cohort and the pooled cohort

| HARVEST-Malmö N=322 | GREAT Network Rome N=208 | Pooled cohort N=530 | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 75.1±11.1 | 78.5±9.9 | 76.4±10.7 | <0.001 |

| Female sex (%) | 97 (30.1) | 114 (54.8) | 211 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (%) | 38 (11.8) | 29 (13.9) | 67 (12.6) | 0.450 |

| Clinical profile, n (%) | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 137.3±27.5 | 150.7±33.7 | 142.3±30.8 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 73.6±12.6 | 81.4±16.8 | 77.0±14.9 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 38 (24–52) | 40 (27–50) | 40 (25–50) | 0.036 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 119 (37.0) | 75 (36.1) | 194 (36.6) | 0.720 |

| Prior heart failure | 200 (62.1) | 85 (40.9) | 285 (53.8) | <0.001 |

| Prevalent atrial fibrillation | 153 (47.5) | 96 (46.2) | 249 (47.0) | 0.762 |

| Medication, n (%) | ||||

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 251 (77.9) | 109 (52.4) | 360 (67.9) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 279 (86.6) | 101 (48.6) | 380 (71.7) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics | 306 (95.0) | 132 (63.5) | 438 (82.6) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| Bio-ADM (pg/mL) | 39.6 (25.6–64.5) | 24.6 (9.5–48.4) | 34.6 (18.7–59.3) | <0.001 |

| penKid (pmol/L) | 85.3 (62.8–118.4) | 109.5 (81.7–168.5) | 91.8 (67.9–135.9) | <0.001 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | – | 756 (366–1452) | – | – |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 4096 (2212–8645) | 7811 (2038–10851) | – | – |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) admission | 1.32±0.64 | 1.44±0.91 | 1.37±0.76 | 0.069 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) after 48 hours | 1.35±0.64 | 1.53±1.0 | 1.42±0.81 | 0.016 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.8±0.5 | 4.3±0.6 | 4.0±0.6 | <0.001 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140.5±3.3 | 137.3±5.9 | 139.2±4.7 | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 127.6±18.3 | 123.2±24.8 | 125.9±21.2 | 0.019 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Peripheral oedema (n (%)) | 215 (58.0) | 145 (59.2) | 338 (63.4) | 0.004 |

| WRF (n (%)) | 30 (8.1) | 37 (20.7) | 67 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (n (%)) | 7 (1.9) | 17 (8.2) | 24 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| 1-year mortality (n (%)) | 50 (17.2) | – | – | – |

| Rehospitalisation (n (%)) | 188 (66.2) | – | – | – |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 7 (4–9) | 6 (3–8) | 6 (4–9) | 0.320 |

Continuous data presented as mean±SD or median (Q1–Q3), depending on distribution.

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker;BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide;CXR, chest X-ray;HARVEST, HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial; NT-proBNP, N-terminal proBNP;bio-ADM, bioactive adrenomedullin; penKid, proenkephalin A 119–159.

openhrt-2019-001048supp002.docx (13.5KB, docx)

Congestion

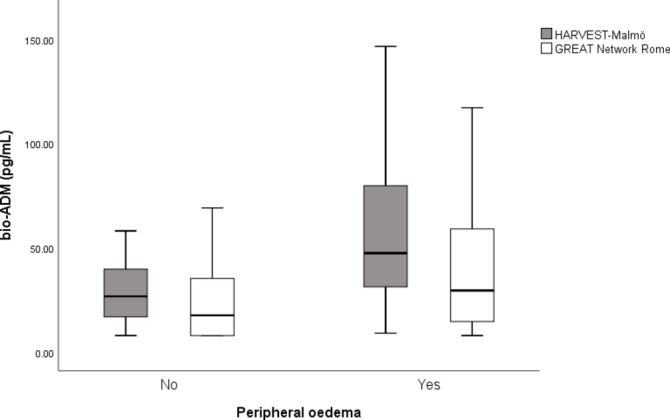

The ROC analyses for bio-ADM and peripheral oedema resulted in an AUC of 0.745 (95% CI 0.684 to 0.807) (HARVEST-Malmö), 0.651 (95% CI 0.576 to 0.726) (GREAT Network Rome) and 0.710 (95% CI 0.663 to 0.757) (pooled cohort). Logistic regression analyses carried out for bio-ADM and each sign of congestion (dyspnoea, oedema, signs of pulmonary oedema on chest X-ray and lung rales) revealed that each one SD increment of bio-ADM was significantly associated with peripheral oedema (table 2). The distribution of bio-ADM according to peripheral oedema for each centre is illustrated in figure 1. Analyses of bio-ADM and severe congestion (congestions score of 4) revealed significant associations between each one SD increment of bio-ADM and risk of having the highest congestion score; however, those associations are driven mainly by the presented associations of bio-ADM and peripheral oedema (table 2). Subgroup analyses revealed that the association of bio-ADM and peripheral oedema was present and significant in both sexes when analysed separately (men: OR 2.46 (95% CI 1.63 to 3.69); p<0.001 and women: OR 2.17 (95% CI 1.56 to 3.03); p<0.001) in fully adjusted model.

Table 2.

Associations of bio-ADM and congestion

| Univariable model | HARVEST-Malmö | GREAT Network Rome | Pooled cohort | ||||||

| N; events | OR (95% CI) | P value | N; events | OR (95% CI) | P value | N; events | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Peripheral oedema | 276; 200 | 2.93 (2.04 to 4.21) | <0.001 | 192; 116 | 1.71 (1.24 to 2.36) | <0.001 | 486; 322 | 2.22 (1.76 to 2.80) | <0.001 |

| Persistent dyspnoea | 295; 272 | 1.03 (0.67 to 0.58) | 0.888 | 191; 177 | 0.76 (0.46 to 1.23) | 0.302 | 486; 449 | 0.90 (0.64 to 1.24) | 0.507 |

| Congestion on X-ray | 274; 239 | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.39) | 0.914 | 188; 169 | 1.11 (0.68 to 1.79) | 0.677 | 462; 408 | 0.99 (0.75 to 1.33) | 0.997 |

| Rales | 291; 209 | 0.96 (0.75 to 1.23) | 0.746 | 192; 160 | 1.09 (0.74 to 1.61) | 0.650 | 483; 364 | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.15) | 0.498 |

| Severe congestion | 253; 122 | 1.59 (1.22 to 2.06) | <0.001 | 187; 76 | 1.30 (0.97 to 1.75) | 0.077 | 440; 198 | 1.47 (1.21 to 1.78) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Peripheral oedema | 276; 200 | 3.12 (2.14 to 4.56) | <0.001 | 192; 116 | 1.69 (1.22 to 2.35) | 0.002 | 486; 322 | 2.29 (1.81 to 2.91) | <0.001 |

| Persistent dyspnoea | 295; 272 | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.59) | 0.852 | 191; 177 | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.21) | 0.213 | 486; 449 | 0.92 (0.66 to 1.29) | 0.239 |

| Congestion on X-ray | 274; 239 | 0.97 (0.68 to 1.38) | 0.967 | 188; 169 | 1.12 (0.69 to 1.82) | 0.653 | 462; 408 | 0.98 (0.73 to 1.29) | 0.867 |

| Rales | 291; 209 | 0.96 (0.75 to 1.24) | 0.780 | 192; 160 | 1.11 (0.75 to 1.64) | 0.598 | 483; 364 | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.19) | 0.722 |

| Severe congestion | 253; 122 | 1.65 (1.26 to 2.17) | <0.001 | 187; 76 | 1.27 (0.94 to 1.71) | 0.115 | 440; 198 | 1.48 (1.21 to 1.80) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Peripheral oedema | 276; 200 | 3.01 (2.02 to 4.47) | <0.001 | 192; 116 | 1.79 (1.26 to 2.54) | 0.001 | 486; 322 | 2.30 (1.29 to 2.97) | <0.001 |

| Persistent dyspnoea | 295; 272 | 0.97 (0.61 to 1.55) | 0.903 | 191; 177 | 0.79 (0.45 to 1.39) | 0.451 | 486; 449 | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.36) | 0.948 |

| Congestion on X-ray | 274; 239 | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.34) | 0.702 | 188; 169 | 0.99 (0.58 to 1.69) | 0.973 | 462; 408 | 0.90 (0.67 to 1.22) | 0.491 |

| Rales | 291; 209 | 0.94 (0.71 to 1.25) | 0.680 | 192; 160 | 1.18 (0.78 to 1.80) | 0.436 | 483; 364 | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.24) | 0.884 |

| Severe congestion | 253; 122 | 1.58 (1.18 to 2.11) | <0.002 | 187; 76 | 1.33 (0.97 to 1.82) | 0.079 | 440; 198 | 1.46 (1.18 to 1.80) | <0.001 |

Values are OR with 95% CI for associations of bio-ADM and each sign of congestion, as well as bio-ADM and severe congestion (highest values on the congestion score (CCS=4). Model 1 is age and sex adjusted. Model 2 is further adjusted for systolic blood pressure, log-transformed and normalised B-type natriuretic peptide, prevalent atrial fibrillation and prior heart failure.

CCS, clinical congestion score; HARVEST, HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial; bio-ADM, bioactive adrenomedullin.

Figure 1.

Distribution of bio-ADM according to signs of peripheral oedema within each centre. HARVEST-Malmö n=301, 215 events (p<0.001), GREAT Network Rome n=208, 123 events (p=0.080). bio-ADM, bioactive adrenomedullin, HARVEST, HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial.

Worsening renal function

Spearman correlation analyses for penKid and plasma creatinine at admission resulted in R of 0.577 (p<0.001) (HARVEST-Malmö), 0.645 (p<0.001) (GREAT Network Rome) and 0.598 (p<0.001) (pooled cohort).

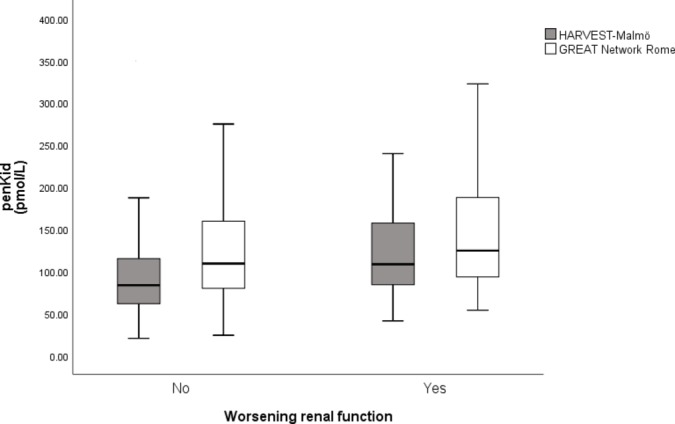

The ROC analyses for penKid and WRF resulted in an AUC of 0.654 (95% CI 0.552 to 0.757) (HARVEST-Malmö), 0.591 (95% CI 0.490 to 0.692) (GREAT Network Rome) and 0.652 (95% CI 0.583 to 0.721) (pooled cohort). In crude logistic regression models, and further adjusted for diabetes, SBP, ACEi, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers, prior heart failure, creatinine and BNP in the pooled cohort, penKid was associated with WRF (table 3). Further, we also analysed WRF using the delta creatinine (creatine after 48 hours—creatinine at admission) as a dependent variable in multivariate linear regression analyses, and the analyses revealed significant associations between penKid and delta creatinine (crude model (β −0.422; p=0.002); multivariate model adjusted for diabetes, SBP, ACEi, ARB, beta-blockers, prior heart failure, creatinine and BNP (β −0.392; p=0.004) in the pooled cohort. The distribution of penKid according to WRF for each centre is illustrated in figure 2. Subgroup analyses revealed that the association of penKid and WRF was present and significant in men (OR 3.72 (95% CI 2.00 to 6.92); p<0.001), but only a trend was seen in women (OR 1.42 (95% CI 0.98 to 2.05); p=0.063) in fully adjusted model.

Table 3.

Associations of penKid and worsening renal function

| Univariable | HARVEST-Malmö | GREAT Network Rome | Pooled cohort | ||||||

| N=323 (30 events) | N=178 (37 events) | N=501 (67 events) | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.02 | 0.299 | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.04 | 0.715 | 1.00 | 0.98 to 1.03 | 0.932 |

| Sex | 6.72 | 1.57 to 28.8 | 0.010 | 0.94 | 0.48 to 1.84 | 0.847 | 1.22 | 0.73 to 2.04 | 0.443 |

| Diabetes | 1.40 | 0.65 to 3.03 | 0.389 | 1.12 | 0.56 to 2.2 | 0.751 | 1.23 | 0.74 to 2.04 | 0.425 |

| SBP | 1.00 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.621 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.158 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.100 |

| ACE-i | 0.72 | 0.34 to 1.52 | 0.384 | 1.32 | 0.66 to 2.64 | 0.432 | 0.83 | 0.51 to 1.37 | 0.468 |

| ARB | 0.60 | 0.22 to 1.64 | 0.320 | 0.52 | 0.21 to 1.31 | 0.165 | 0.54 | 0.28 to 1.06 | 0.074 |

| Betablockers | 1.32 | 0.38 to 4.56 | 0.665 | 1.20 | 0.61 to 2.36 | 0.590 | 0.81 | 0.47 to 1.39 | 0.444 |

| Prior HF | 1.14 | 0.84 to 1.55 | 0.407 | 0.71 | 0.35 to 1.42 | 0.330 | 0.90 | 0.62 to 1.31 | 0.590 |

| Creatinine | 2.73 | 1.79 to 4.18 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 0.83 to 1.62 | 0.396 | 1.63 | 1.28 to 2.08 | <0.001 |

| BNP | 1.16 | 0.79 to 1.70 | 0.459 | 0.90 | 0.64 to 1.26 | 0.532 | 1.01 | 0.78 to 1.29 | 0.966 |

| PenKid | 1.81 | 1.21 to 2.70 | 0.004 | 1.37 | 0.99 to 1.89 | 0.059 | 1.67 | 1.31 to 2.14 | <0.001 |

| Multivariable | |||||||||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.01 | 0.173 | ||||||

| Sex | 1.54 | 0.80 to 2.98 | 0.197 | ||||||

| Diabetes | 0.92 | 0.51 to 1.66 | 0.919 | ||||||

| SBP | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.373 | ||||||

| ACEi | 0.80 | 0.43 to 1.50 | 0.483 | ||||||

| ARB | 0.47 | 0.21 to 1.04 | 0.063 | ||||||

| BB | 0.98 | 0.50 to 1.91 | 0.946 | ||||||

| Prior HF | 1.02 | 0.72 to 1.43 | 0.926 | ||||||

| BNP | 0.78 | 0.57 to 1.06 | 0.115 | ||||||

| Creatinine | 1.68 | 0.69 to 4.05 | 0.251 | ||||||

| PenKid | 1.74 | 1.20 to 2.53 | 0.004 | ||||||

Values are OR with 95% CI. Multivariable results are reported for the pooled cohort adjusted for variables known from literature.

ACE-I, ACE inhibitors;ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker;BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide;HARVEST, HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial; HF, heart failure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; penKid, proenkephalin A 119–159.

Figure 2.

Distribution of penKid according to worsening renal function in each centre. HARVEST-Malmö n=323, 30 events (p=0.003), GREAT Network Rome n=178, 37 events (p=0.050). PenKid, proenkephalin A 119–159HARVEST, HeArt and bRain failure inVESTigation trial.

In-hospital mortality

Bioactive adrenomedullin

Univariable and bivariable logistic regression models exploring associations of bio-ADM with in-hospital mortality are presented in table 4 (n=470; 24 events). As for ROC analyses, the AUC for bio-ADM and in-hospital mortality was 0.614 (95% CI 0.467 to 0.761) (HARVEST-Malmö), 0.657 (95% CI 0.507 to 0.807) (GREAT Network Rome) and 0.606 (95% CI 0.483 to 0.729) (pooled cohort). Subgroup analyses revealed that the association of bio-ADM and in-hospital mortality was present and significant in men (OR 1.76 (95% CI 1.04 to 2.97); p=0.034), but not in women (OR 1.33 (95% CI 0.69 to 2.56); p=0.394). However, due to the low number of events when analysed separately, those results should be interpreted with caution.

Table 4.

Logistic regression model for in-hospital mortality for bio-ADM and penKid

| Univariable | Bivariable: BioADM | Bivariable: PenKid | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.04 | 0.99 to 1.09 | 0.067 | 1.54 | 1.03 to 2.31 | 0.037 | 2.16 | 1.49 to 3.13 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.53 | 0.24 to 1.16 | 0.112 | 1.58 | 1.05 to 2.37 | 0.028 | 2.19 | 1.53 to 3.14 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.85 | 0.37 to 1.92 | 0.689 | 1.52 | 1.01 to 2.28 | 0.045 | 2.23 | 1.56 to 3.19 | <0.001 |

| SBP | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.254 | 1.48 | 0.98 to 2.25 | 0.063 | 2.28 | 1.59 to 3.27 | <0.001 |

| ACE-i | 0.60 | 0.26 to 1.36 | 0.217 | 1.49 | 0.99 to 2.23 | 0.056 | 2.24 | 1.56 to 3.21 | <0.001 |

| ARB | 0.92 | 0.46 to 1.81 | 0.798 | 1.51 | 1.01 to 2.27 | 0.049 | 2.27 | 1.58 to 3.25 | <0.001 |

| Betablockers | 0.20 | 0.09 to 0.46 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 1.08 to 2.40 | 0.020 | 2.08 | 1.44 to 3.00 | <0.001 |

| Prior HF | 0.54 | 0.25 to 1.19 | 0.127 | 1.63 | 1.09 to 2.46 | 0.018 | 2.22 | 1.56 to 3.15 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine | 1.77 | 1.27 to 2.46 | 0.001 | 1.38 | 0.90 to 2.11 | 0.139 | 2.31 | 1.51 to 3.53 | <0.001 |

| BNP | 1.28 | 0.85 to 1.92 | 0.235 | 1.42 | 0.93 to 2.15 | 0.105 | 2.29 | 1.56 to 3.35 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.43 | 0.10 to 1.84 | 0.255 | 1.47 | 0.97 to 2.21 | 0.067 | 2.25 | 1.57 to 3.23 | <0.001 |

| Prevalent AF | 0.47 | 0.20 to 1.09 | 0.078 | 1.50 | 1.01 to 2.25 | 0.047 | 2.18 | 1.53 to 3.11 | <0.001 |

| Bio-ADM | 1.50 | 1.00 to 2.26 | 0.051 | 2.19 | 1.52 to 3.15 | <0.001 | |||

| penKid | 2.24 | 1.57 to 3.20 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 0.88 to 2.03 | 0.168 | |||

Values are OR with 95% CI. All results are reported for the pooled cohort (n=470, 24 events). Univariable results are presented as each variable’s associations with in-hospital mortality. Bivariable results are reported for penKid and bio-ADM, adjusted for each variable separately.

ACE-I, ACE inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; Bio-ADM, bioactive adrenomedullin; HF, heart failure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; penKid, proenkephalin A 119–159.

Proenkephalin

Univariable and bivariable logistic regression models exploring associations of penKid with in-hospital mortality are presented in table 4, where penKid was associated with in-hospital mortality in all analyses. The ROC analyses for penKid and in-hospital mortality resulted in an AUC of 0.630 (95% CI 0.396 to 0.864) (HARVEST), 0.732 (95% CI 0.596 to 0.868) (GREAT Network Rome) and 0.735 (95% CI 0.618 to 0.851) (pooled cohort). Subgroup analyses revealed that the association of penKid and in-hospital mortality was present and significant in both sexes when analysed separately (women: OR 1.78 (95% CI 1.06 to 3.00); p=0.029 and men: OR 2.71 (95% CI 1.59 to 4.62); p<0.001).

One-year mortality

Due to the low event rate for in-hospital mortality in HARVEST-Malmö, we performed additional analyses of biomarkers and 1-year mortality (n=290, 50 events).

Bioactive adrenomedullin

ROC analyses of bio-ADM for 1-year mortality resulted in an AUC of 0.586 (95% CI 0.502 to 0.669), p=0.044. Cox regression models revealed that each one SD increment in bio-ADM was associated with increased 1-year mortality in the crude model (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.74, p=0.029), age-adjusted and sex-adjusted model (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.72, p=0.029) and further adjusted for diabetes, SBP, atrial fibrillation, smoking, NT-proBNP and prior heart failure (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.79, p=0.043).

Proenkephalin

ROC analyses of penKid and 1-year mortality resulted in an AUC of 0.639 (95% CI 0.549 to 0.729), p=0.001. Cox regression models revealed that each one SD increment in penKid levels was associated with increased 1-year mortality in crude analyses (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.31 to 2.10, p<0.001), in an age-adjusted and sex-adjusted model (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.94, p=0.004) and further adjusted for diabetes, SBP, atrial fibrillation, smoking, NT-proBNP and prior heart failure (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.77, p=0.027).

Rehospitalisation

Bioactive adrenomedullin

ROC analyses of bio-ADM and rehospitalisation resulted in AUC of 0.585 (95% CI 0.517 to 0.654), p=0.017. Analyses of bio-ADM and risk of rehospitalisation (n=284; 188 events; mean follow-up time 174 days) were carried out in a crude model (HR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.36, p=0.008), age-adjusted and sex-adjusted model (HR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.36, p=0.008) and further adjusted for diabetes, SBP, atrial fibrillation, smoking, log-transformed and z-normalised BNP and prior heart failure (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.47, p=0.007) and revealed that each one SD increment of bio-ADM was associated with increased risk of rehospitalisation.

Proenkephalin

Analyses of penKid and risk of rehospitalisation revealed that there were no significant associations (data not shown).

Length of hospital stay

Bioactive adrenomedullin

In linear regression analyses in the pooled cohort, each one SD increment of bio-ADM was associated with longer hospital stay on admission in crude analysis (β 0.700; p=0.004), in age-adjusted and sex-adjusted analysis (β 0.709; p=0.003), and remained so after further adjustment for diabetes, SBP, prevalent atrial fibrillation, smoking and prior heart failure (β 0.702; p=0.005).

Proenkephalin

In linear regression analyses, no significant associations were seen for penKid and length of hospital stay (data not shown).

Discussion

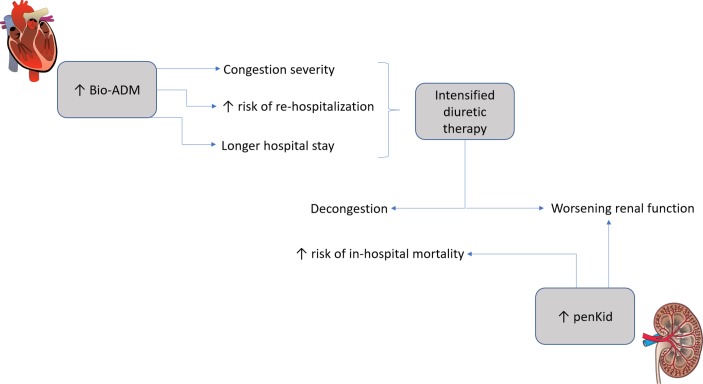

In this observational study of two AHF cohorts, we could show that bio-ADM was a suitable biomarker for early detection and quantification of congestion severity (mainly driven by peripheral oedema), risk of rehospitalisation and longer hospital stay, while penKid was a suitable biomarker in detection of WRF occurrence and both in-hospital and 1-year mortality. This is, to our knowledge, the first time that data regarding penKid and bio-ADM are presented when used simultaneously in patients with AHF in two independent cohorts. These data imply that in an everyday clinical setting, bio-ADM and penKid could be useful to guide diuretic therapy. Since increased bio-ADM is associated with clinical congestion, this might be used to identify individuals with the need of intensified diuretic therapy. As treatment of AHF and decongestion might be harmful to the kidneys, the combination of the two biomarkers appears advantageous, where penKid can aid in guiding the treatment so not to jeopardise renal function (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The clinical use of Bioactive adrenomedullin (bio-ADM) and proenkephalin A 119–159 (penKid) for management of heart failure.

Bioactive adrenomedullin

Bio-ADM is known as a vasodilation factor,18 and the prognostic value of bio-ADM has been shown in several different critical conditions.8 19 20 Moreover, its predictive role was recently extended to the AHF setting. Self et al showed that in patients with AHF, higher bio-ADM levels were associated with the composite primary outcome consisting of death, rehospitalisation, emergency dialysis, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, respiratory failure, prolonged hospitalisation and acute coronary syndrome within 30 days.10 Furthermore, they suggested that bio-ADM provides predictive information independent of more established biomarkers in AHF such as natriuretic peptides and troponins. This view is supported by our findings where bio-ADM predicted 1-year mortality and in-hospital mortality. The confirmation of congestion by laboratory results is, at present, challenging, and the evaluation of bio-ADM might provide a new opportunity to guide clinical decisions. In this context, our findings showing high levels of bio-ADM to be associated with increased length of hospital stay and increased risk of rehospitalisation are of great interest, suggesting bio-ADM as a possible new tool to pinpoint which patients could benefit from a more active treatment in order to reduce length of stay and risk of readmission. This reasoning is further supported by a recent study by Kremer et al9 that showed a significant decrease in bio-ADM for admitted patients with AHF with little or no residual congestion after 1 week, compared with patients with significant residual congestion. Further, bio-ADM was the strongest predictor of prevalent congestion among 13 covariates.9 Recently, a promising drug candidate (adrecizumab) targeting bio-ADM has been developed.21 22

Proenkephalin

PenKid is considered an inflammation-independent marker of kidney function that allows the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury by predicting the future change in serum creatinine.23 Its highly dynamic nature enables close monitoring of renal function. In our study, penKid correlated with serum creatinine levels. In addition, penKid was associated with WRF and both in-hospital and 1-year mortality. These results are in line with Ng et al’s study in the AHF setting,15 as well as in the stable heart failure setting.24

The pathophysiological mechanism suggested for penKid, both in WRF and its prognostic value in mortality, might be related to cardiodepressive effects of enkephalins11 which would cause reduced kidney perfusion and advancing heart failure. This theory is supported by the results from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry where administration of opiates resulted in worse prognosis in heart failure.25

Even if bio-ADM and penKid most likely reflect different pathophysiological mechanisms (ie, bio-ADM and congestion, penKid and WRF), the combination of the two could yield complementary information regarding the cardiorenal syndrome in patients with AHF. Further prospective studies are indeed warranted.

Study limitations

An important strength of the current study is the use of two well-characterised prospective AHF cohorts. There are, however, several limitations with this study. The two cohorts, while fairly comparable in age and have a medical history, differ significantly in use of medications as well as mortality rate with a lower event rate in the HARVEST cohort. This is most likely due to the fact that patients in the HARVEST cohort were recruited from the wards, while the patients in the GREAT Network Rome cohort were recruited directly from the emergency department. Consequently, treatment for AHF (ie, diuretics) was already initiated in most patients in the HARVEST cohort. The low-event rate is also most likely an effect of this as the most severe cases of AHF with the worst prognosis would be treated in the intensive care unit or the cardiac intensive care unit and not in one of the participating recruiting wards in the HARVEST cohort. The aetiology of heart failure was not registered. Data on signs of congestion, which was the basis for our congestion score, were not collected per protocol prospectively, but gathered retrospectively from the admittance record and thus subjected to the admitting doctor’s precision and record-keeping. This could explain the lack of significance for the congestive signs other than peripheral oedema, as they presumably are more subjective and more prone to include conditions other than congestion. Data on congestion at discharge was not available, and we acknowledge that assessment of residual congestion at discharge would have added value to the study, especially paired with serial measurements of bio-ADM and penKid. Finally, the study was undertaken in individuals of mainly European descent, and the conclusions may not be generalisable to all ancestries.

Conclusion

In two separate AHF cohorts, bio-ADM and penKid perform as suitable biomarkers for early detection of congestion severity and WRF occurrence, respectively, and are both associated with adverse clinical outcomes. The simultaneous evaluation of the two biomarkers in patients with AHF could provide important information in therapeutic decision-making in order to reduce patient’s mortality, in-hospital length of stay and rehospitalisation rate. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Footnotes

SDS and MM contributed equally.

Contributors: All authors substantially contributed to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: MM was supported by grants from the Medical Faculty of Lund University Skane University Hospital, the Crafoord Foundation, the Ernhold Lundstroms Research Foundation, the Region Skane, the Hulda and Conrad Mossfelt Foundation, the Southwest Skanes Diabetes Foundation, the Kockska foundation, the Research Funds of Region Skåne and the Swedish Heart and Lung foundation, the Wallenberg Center for Molecular Medicine, Lund University, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation. Role of the Sponsors: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: OH, AB and JS are employed by Sphingotec GmbH, the company that provides the penKid and bio-ADM assays used in this study. EB is an employee of Astra Zeneca.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board at Lund University, Sweden (HARVEST-Malmö) and by the Ethical Committee of Sapienza University (GREAT Network Rome).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, et al. . Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1527–39. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Somma S, Magrini L, Pittoni V, et al. . In-hospital percentage BNP reduction is highly predictive for adverse events in patients admitted for acute heart failure: the Italian RED Study. Crit Care 2010;14 10.1186/cc9067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen-Solal A, Laribi S, Ishihara S, et al. . Prognostic markers of acute decompensated heart failure: the emerging roles of cardiac biomarkers and prognostic scores. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2015;108:64–74. 10.1016/j.acvd.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Law C, Glover C, Benson K, et al. . Extremely high brain natriuretic peptide does not reflect the severity of heart failure. Congest Heart Fail 2010;16:221–5. 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omar HR, Guglin M. Extremely elevated BNP in acute heart failure: patient characteristics and outcomes. Int J Cardiol 2016;218:120–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felker GM, Anstrom KJ, Adams KF, et al. . Effect of natriuretic peptide–guided therapy on hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality in high-risk patients With heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:713–20. 10.1001/jama.2017.10565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano S, Imamura T, Matsuo T, et al. . Differential responses of circulating and tissue adrenomedullin and gene expression to volume overload. J Card Fail 2000;6:120–9. 10.1054/jcaf.2000.7277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marino R, Struck J, Maisel AS, et al. . Plasma adrenomedullin is associated with short-term mortality and vasopressor requirement in patients admitted with sepsis. Crit Care 2014;18 10.1186/cc13731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kremer D, Ter Maaten JM, Voors AA. Bio-adrenomedullin as a potential quick, reliable, and objective marker of congestion in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1363–5. 10.1002/ejhf.1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Self WH, Storrow AB, Hartmann O, et al. . Plasma bioactive adrenomedullin as a prognostic biomarker in acute heart failure. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:257–62. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Brink OWV, Delbridge LM, Rosenfeldt FL, et al. . Endogenous cardiac opioids: enkephalins in adaptation and protection of the heart. Heart Lung Circ 2003;12:178–87. 10.1046/j.1444-2892.2003.00240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino R, Struck J, Hartmann O, et al. . Diagnostic and short-term prognostic utility of plasma pro-enkephalin (pro-ENK) for acute kidney injury in patients admitted with sepsis in the emergency department. J Nephrol 2015;28:717–24. 10.1007/s40620-014-0163-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsue Y, Ter Maaten JM, Struck J, et al. . Clinical correlates and prognostic value of proenkephalin in acute and chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2017;23:231–9. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng LL, Sandhu JK, Narayan H, et al. . Proenkephalin and prognosis after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:280–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng LL, Squire IB, Jones DJL, et al. . Proenkephalin, renal dysfunction, and prognosis in patients with acute heartfailure: a GREAT network study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:56–69. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensson A, Grubb A, Molvin J, et al. . The shrunken pore syndrome is associated with declined right ventricular systolic function in a heart failure population - the HARVEST study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2016;76:568–74. 10.1080/00365513.2016.1223338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damman K, Tang WHW, Testani JM, et al. . Terminology and definition of changes renal function in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3413–6. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinson JP, Kapas S, Smith DM. Adrenomedullin, a multifunctional regulatory peptide. Endocr Rev 2000;21:138–67. 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolppanen H, Rivas-Lasarte M, Lassus J, et al. . Adrenomedullin: a marker of impaired hemodynamics, organ dysfunction, and poor prognosis in cardiogenic shock. Ann Intensive Care 2017;7 10.1186/s13613-016-0229-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuyun MF, Narayan HK, Quinn PA, et al. . Prognostic value of human mature adrenomedullin in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Med 2017;18:42–50. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geven C, Bergmann A, Kox M, et al. . Vascular effects of adrenomedullin and the anti-adrenomedullin antibody adrecizumab in sepsis. Shock 2018;50:132–40. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geven C, Peters E, Schroedter M, et al. . Effects of the humanized anti-adrenomedullin antibody adrecizumab (HAM8101) on vascular barrier function and survival in rodent models of systemic inflammation and sepsis. Shock 2018;50:648–54. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah KS, Taub P, Patel M, et al. . Proenkephalin predicts acute kidney injury in cardiac surgery patients. Clin Nephrol 2015;83:29–35. 10.5414/CN108387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbit B, Marston N, Shah K, et al. . Prognostic usefulness of proenkephalin in stable ambulatory patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1310–4. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peacock WF, Hollander JE, Diercks DB, et al. . Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J 2008;25:205–9. 10.1136/emj.2007.050419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2019-001048supp001.docx (20.4KB, docx)

openhrt-2019-001048supp002.docx (13.5KB, docx)