Abstract

Gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (GC) represents a worldwide problem, this being the fifth most common malignancy. The fragility of patients with GC together with the aggressiveness of this tumour makes it as one of the most difficult neoplasias to manage. This article summarises the main strategies for treating patients with GC. Correct assessment of patients with GC requires a multidisciplinary evaluation and close follow-up. For patients with resectable tumours, perioperative chemotherapy should be always considered, especially in the neoadjuvant setting given its capacity for tumour downstaging and eradication of micro-metastases. In the metastatic setting, first-line and second-line treatment improve survival and quality of life in patients with GC. In this setting, only trastuzumab as first-line therapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive tumours and ramucirumab as second-line therapy have demonstrated a clear survival improvement. The lack of adequate biomarker selection and the intrinsic heterogeneity of these tumours have jeopardised the possible usefulness of many other targeted agents. Finally, when considering GC carcinogenesis as a multiple stepwise process from initial inflammation starting in the gastric epithelia, immune checkpoint inhibitors may improve the survival of these patients, although the optimal setting for their activity has yet to be fully elucidated.

Keywords: gastric cancer, treatment algorithm, gastro-esophageal cancer

Introduction

Gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancers (GC) are the third cause of cancer-related deaths,1 representing an international problem which needs precise individualised treatment. While the incidence of gastric cancer is globally decreasing, the contrary is occurring for proximal and junctional tumours.2 These epidemiological distinctions are sustained by various associated risk factors which ultimately potentiate the occurrence of different molecularly driven tumours within the stomach. According to the Cancer Genome Atlas,3 four molecular subtypes of GC have been identified, with inherent genetic features. Also important is the particular need for recognition of GC heterogeneity, not only to understand the failure of multiple phase III studies with targeted agents carried out over the last few years but also to provide physicians with adequate guided strategies.

Diagnosis, staging and treatment planning

Patients with GC represent a particularly fragile population. Symptomatology normally only appears once the tumour has increased in size to the point where it interferes with the nutritional process, resulting in these patients presenting with significant asthenia, difficulty for tolerating normal food (nausea, vomiting and early satiety), anaemia and non-depreciable weight loss. Correct evaluation of patients with GC requires particular consideration of supportive care and nutritional assessment.

Diagnosis of GC should be made from a gastroscopy with a biopsy, including histology reported according to the WHO criteria,4 together with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) receptor status (at least in metastatic cases). Staging is normally assessed by a thoracoabdominal CT scan. However, a positron emission tomography-CT scan might be necessary in cases with suspicious metastatic spread, while an exploratory laparoscopy may rule out peritoneal spread in cases considered upfront to be potentially resectable, and an endoscopic ultrasound may improve the accuracy of staging in locally advanced cases. The TNM stage should be reported according to the latest edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control guidelines and staging manual.5 The evaluation of each patient with GC should always include a precise anamnesis and physical examination including weight, a differential blood count, as well as liver and renal function tests. Testing for tumour markers (CEA, CA19.9 and CA72.4), although not mandatory, may be helpful especially for detecting recurrences during follow-up, and anticipating progression in the metastatic setting. A thorough approach would ideally include a multidisciplinary tumour board, especially in locally advanced and resectable cases.

Management of local/locoregional disease

Surgery represents the cornerstone of curative treatment, although recurrences occur in more than 50% of cases.6 Indeed, GC should be considered a systemic disease from the start of care, such that treatment with systemic perioperative chemotherapy potentiates the downstaging and eradication of microscopic metastases. Endoscopic resection (if cT1a, clearly confined to the mucosa, well differentiated, ≤2 cm and non-ulcerated) or surgery alone can only be recommended for stage I disease. For stages Ib–III, perioperative treatment is mandatory.

The type of the surgery depends on the location of the tumour. Subtotal gastrectomies may only be carried out if a macroscopic proximal margin of at least 5 cm between the tumour and the gastro-oesophageal junction can be achieved (otherwise a total gastrectomy is mandatory). A D2 lymph node dissection is recommended, with the removal of perigastric lymph nodes plus those along the left gastric, common hepatic and splenic arteries and the coeliac axis, with a minimum of 15 lymph nodes removed. Only specialised, high-volume institutions with appropriate surgical expertise and postoperative care should be considered for performing these complex resections.

Perioperative (preoperative and postoperative) chemotherapy with a platinum and a fluoropyrimidine combination is recommended for patients with stage >Ib. The phase III UK Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy (MAGIC) trial6 demonstrated an improvement in 5year overall survival (OS) from 23% to 36% with six cycles of perioperative epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (ECF) chemotherapy, compared with surgery alone in patients with stages II and III GC. A French study7 demonstrated similar results with perioperative cisplatin plus 5-FU in a 28-day regimen, although it included a greater proportion of patients with proximal tumours, compared with the MAGIC trial. Finally, an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer study with a weekly schema of cisplatin and 5-FU demonstrated an increase in R0 resection rates in patients receiving chemotherapy plus surgery compared with those with surgery alone.8 This study was closed early due to poor accrual and consequently was not powered to show differences in OS. These three phase III trials established perioperative treatment as the gold standard in European patients, with the schema from the MAGIC trial being the most widely accepted. Nevertheless, this paradigm radically changed in 2017 when the OS results from the German AIO study group demonstrated greater benefit with the addition of taxanes to the platinum-5-FU doublet.9 This study compared the fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, docetaxel (FLOT) regimen versus ECF/X. Patients treated with FLOT presented a higher pathological response rate and a large improvement in survival (HR 0.77, p=0.012). Global toxicity rates were similar in both groups, although patients treated with FLOT presented more leucopenia/neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy.

Unfortunately, some patients with GC with stage >Ib are not eligible for perioperative treatment, mainly due to age and/or comorbidities or because of an urgent surgery requirement (when debuting with initial refractory bleeding or highly occlusive tumours). In this setting, adjuvant treatment after surgery either with chemoradiotherapy or with chemotherapy alone can be considered. The North American Intergroup-0116 trial demonstrated an OS benefit in patients who received postoperative 5-FU-based chemoradiotherapy,10 although most of the patients had been treated with inadequate lymphadenectomy (less than D1). The results of the study suggested that postoperative treatment might compensate suboptimal surgery. Similar findings in the Dutch D1D2 trial corroborated this, demonstrating a greater survival benefit in patients who had undergone D1 (not D2) lymphadenectomies or R1 resections.11 12 Moreover, the phase III ChemoRadiotherapy after Induction chemoTherapy In Cancer of the Stomach (CRITICS) trial,13 which evaluated adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in patients who had received preoperative chemotherapy and surgery, confirmed the limited benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy. Finally, an Asian study reinforced the benefit of the adjuvancy with chemotherapy alone, demonstrating a benefit of performing 6 months of capecitabine–oxaliplatin after radical surgery in patients who had undergone R0 resection with an adequate lymphadenectomy but without having received preoperative chemotherapy.14

Management of advanced/metastatic disease (chemotherapy, targeted agents, immunotherapy)

First-line treatment

Patients with locally advanced unresectable and/or metastatic disease should be considered for systemic treatment (chemotherapy), which has consistently demonstrated a benefit in both OS and quality of life.15 The standard of care is based on a platinum (cisplatin or oxaliplatin) and a fluoropyrimidine doublet (5-FU, capecitabine, tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (S-1)). Patients with HER-2 overexpression (immunohistochemistry (IHC) 3+ or IHC 2+ and in situ hybridisation positive) should also receive trastuzumab (table 1a).

Table 1.

Main phase III clinical trials with chemotherapy (A and B) and targeted therapies (C).

| Clinical trial | N | Treatment | OS | PFS | ORR | P value | ||

| (A) First-line chemotherapy treatment | ||||||||

|

The V325 Trial Van Cutsem J Clin Oncol 2006 |

445 | DPF PF |

9.2 m 8.6 m |

HR 1.29 p=0.02 |

5.6 m* 3.7 m |

HR 1.47 p<0.01 |

37% 25% |

0.01 |

|

The Randomized ECF for Advanced and Locally Advanced Esophagogastric Cancer 2 (REAL-2) Trial Cunningham NEJM 2008 |

1002 | EPF EPC EOF EOC |

9.9 m 9.9 m 9.3 m 11.2 m |

Non-inferiority meet | 6.2 m 6.7 m 6.5 m 7 m |

40.7% 46.4% 42.4% 47.9% |

||

|

The ML17302 Trial Kang Ann Oncol 2009 |

316 | CP FP |

10.5 m 9.3 m |

HR 0.85 p=0.008 |

5.6 m 5.0 m |

HR 0.81 p<0.01 |

46% 32% |

0.020 |

|

The FLAGS Trial Ajani J Clin Oncol 2010 |

1053 | P-S1 P-F |

8.6 m 7.9 m |

HR 0.92 p=0.2 |

4.8 m 5.5 m |

HR 0.99 p=0.92 |

29.1% 31.9% |

0.40 |

|

The French Intergroup Trial Guimbaud J Clin Oncol 2014 |

416 | EPC FOLFIRI |

9.49 m 9.72 m |

HR 1.01 p=0.95 |

5.29 m 5.75 m |

HR 0.99 p=0.96 |

39.2% 37.8% |

|

| (B) Second-line treatment and beyond | ||||||||

|

The Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) Trial Thuss-Patience Eur J Can 2011 |

40 | CPT-11 BSC |

4.0 m 2.4 m |

HR 0.48 p=0.012 |

2.6 m – |

0% – |

||

|

The Salvage Chemo Trial Kang J Clin Oncol 2012 |

188 | D/CPT-11 BSC |

5.3 m 3.8 m |

HR 0.65 p=0.007 |

– |

13% – |

||

|

The COUGAR-02 Trial Ford Lancet Oncol 2014 |

168 | D BSC |

5.2 m 3.6 m |

HR 0.67 p=0.01 |

7% – |

|||

| The West Japan Oncology Group (WJOG) Trial 4007 (WJOG 4007) Hironaka J Clin Oncol 2013 |

223 | Pac CPT-11 |

9.5 m 8.4 m |

HR 1.13 p=0.38 |

3.6 m 2.3 m |

HR 1.14 p=0.33 |

20.9% 13.6% |

0.24 |

|

The KEYNOTE 061 Trial Shitara Lancet 2018 |

592 | Pem Pac |

9.1 m 8.3 m |

HR 0.82 p=0.042 |

1.5 m 4.1 m |

HR 1.27 – |

16% 14% |

– |

|

The TAGS Trial Shitara Lancet Oncol 2018 |

507 | TAS-102 PB |

5.7 m 3.6 m |

HR 0.69 p<0.01 |

2.0 m 1.8 m |

HR 0.57 p<0.01 |

4% 2% |

0.28 |

|

The JAVELIN 300 Trial Bang Ann Oncol 2018 |

371 | Ave CPT-11/Pac |

4.6 m 5.0 m |

HR: 1.1 p=0.81 |

1.4 m 2.7 m |

HR: 1.73 p>0.99 |

2.2% 4.3% |

– |

| (C) Targeted agents | ||||||||

|

The TOGA Trial Bang Lancet 2010 |

594 | CP/FP-T CP/FP |

13.8 m 11.1 m |

HR 0.74 p<0.01 |

6.7 m 5.5 m |

HR 0.71 p<0.01 |

47% 35% |

<0.01 |

|

The TRIO-013/LOGIC Trial Hecht J Clin Oncol 2016 |

545 | OC+L OC |

12.2 m 10.5 m |

HR 0.91 p=0.34 |

6.0 m 5.4 m |

HR 0.82 p=0.038 |

53% 39% |

<0.01 |

|

The JACOB Trial Tabernero Lancet Oncol 2018 |

780 | CP/FP-T-Per CP/FP-T |

17.5 m 14.2 m |

HR 0.84 p=0.057 |

8.5 m 7.0 m |

HR 0.73 p<0.01 |

56.7% 48.3% |

0.026 |

|

The TyTAN (Tykerb With Taxol in Asian HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer) Trial Satoh J Clin Oncol 2014 |

261 | Pac +L Pac |

11.0 m 8.9 m |

HR 0.84 p=0.104 |

5.4 m 4.4 m |

HR 0.85 p=0.244 |

27% 9% |

<0.01 |

|

The GATSBY Trial Tuss-Patience Lancet Oncol 2017 |

345 | T-DM1 D/Pac |

7.9 m 8.6 m |

HR 1.15 p=0.86 |

2.7 m 2.9 m |

HR 1.13 p=0.31 |

20.6% 19.6% |

0.840 |

|

The Erbitux (cetuximab) in combination with Xeloda (capecitabine) and cisplatin in advanced esophago-gastric cancer (EXPAND) Trial Lordick Lancet Oncol 2013 |

904 | CP-Cet CP |

9.4 m 10.7 m |

HR 1.00 p=0.95 |

4.4 m 5.6 m |

HR 1.09 p=0.32 |

30% 29% |

0.77 |

|

The REAL3 Trial Waddell Lancet Oncol 2013 |

553 | EOC-Pan EOC |

8.8 m 11.3 m |

HR 1.37 p=0.013 |

6.0 m 7.4 m |

HR 1.22 p=0.068 |

46% 42% |

0.42 |

|

The Avastin in Gastric cancer (AVAGAST) Trial Ohtsu J Clin Oncol 2011 |

774 | CP-Bev CP |

12.1 m 10.1 m |

HR 0.87 p=0.100 |

6.7 m 5.3 m |

HR 0.80 p=0.003 |

46% 37.4% |

0.031 |

|

The RAINFALL Trial Fuchs Lancet Oncol 2019 |

645 | CP-Ram CP |

11.2 m 10.7 m |

HR 0.96 p=0.68 |

5.7 m† 5.4 m |

HR 0.75 p=0.011 |

41.1% 36.4% |

0.17 |

|

The REGARD Trial Fuchs Lancet 2014 |

355 | Ram PB |

5.2 m 3.8 m |

HR 0.77 p=0.047 |

2.1 m 1.3 m |

HR 0.48 p<0.01 |

3% 3% |

0.76 |

|

The RAINBOW Trial Wilke Lancet Oncol 2014 |

665 | Pac-Ram Pac |

9.6 m 7.4 m |

HR 0.80 p=0.017 |

4.4 m 2.9 m |

HR 0.63 p<0.01 |

28% 16% |

<0.01 |

|

The Apatinib Trial Li J Clin Oncol 2016 |

267 | Apa PB |

6.5 m 4.7 m |

HR 0.70 p=0.015 |

2.6 m 1.8 m |

HR 0.44 p<0.01 |

2.84% 0% |

0.169 |

|

The RILOMET-1 Trial Catenacci Lancet Oncol 2017 |

609 | EPC-Rilo EPC |

8.8 m 10.7 m |

HR 1.34 p=0.003 |

5.6 m 6.0 m |

HR 1.26 p=0.016 |

29.8% 44.6% |

<0.01 |

|

The METGASTRIC Trial Shah Jama Oncol 2016 |

562 | FOLFOX-Ona FOLFOX |

11.0 m 11.3 m |

HR 0.82 p=0.24 |

6.7 m 6.8 m |

HR 0.90 p=0.43 |

46.1% 40.6% |

0.25 |

|

The GOLD Trial Bang Lancet Oncol 2017 |

643 | Pac-O Pac |

8.8 m 6.9 m |

HR 0.79 p=0.026 |

3.7 m 3.2 m |

HR: 0.84 p=0.065 |

17% 11% |

0.055 |

|

The GRANITE-1 Trial Othsu J Clin Oncol 2013 |

656 | Eve PB |

5.4 m 4.3 m |

HR 0.90 p=0.124 |

1.7 m 1.4 m |

HR 0.66 p<0.001 |

4.5% 2.1% |

– |

List of phase III clinical trials in (A) first-line treatment, (B) second-line treatment and beyond and (C) targeted agents. In green, those trials with statistically positive results.

*Time to progression (not PFS).

†Not confirmed by central independent review.

–, not reported; Apa, apatinib;Ave, avelumab;BSC, best supportive care;Bev, bevacizumab;C, capecitabin;CPT-11, irinotecan;Cet, cetuximab;D, docetaxel;E, epirrubicin;Eve, everolimus;FOLFIRI, irinotecan, leucovorin, 5-fluorouracil;FOLFOX, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, 5-fluorouracil;5-FU, 5-fluorouracil;L, lapatinib;O, olaparib;OS, overall survival;OX, oxaliplatin;Ona, onartuzumab;P, cisplatin;PB, placebo;PFS, progression-free survival;Pac, paclitaxel;Pan, panitumumab;Pem, pembrolizumab;Per, pertuzumab;Ram, ramucirumab;Rilo, rilotumumab;T, trastuzumab; TAS-102, trifluridine/tipiracil;m, months.

The addition of epirubicin to a chemotherapy doublet has not definitively demonstrated an OS advantage and slightly increases toxicity. In contrast, the addition of docetaxel offers a small benefit in OS but with considerable toxicity with the original docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-FU (DCF) regimen assessed in the V325 phase III study.16 This latter fact together with the fact that taxanes can be given in the second line makes the use of this drug in the first-line setting rare. The original DCF regimen, or better the analogous and less toxic FLOT regimen,9 should only be considered in young/fit patients and if a very quick response is needed.

To date, no other targeted agents have demonstrated an OS benefit in this setting. The lack of biomarkei stratification and the intrinsic GC heterogeneity have likely contributed to the failure to demonstrate a benefit when using multiple targeted therapies against HER2, epidermal growth factor receptor, MET, the tyrosine kinase receptor activated by the hepatocyte growth factor, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin, vascular endothelial growth factor (first line) and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (table 1b).

Finally, comorbidities, organ function and performance status (PS) must always be taken into consideration when choosing a regimen.

Second-line treatment

Second-line treatment based at a minimum on chemotherapy (paclitaxel, docetaxel or irinotecan) should be considered in patients with PS 0–1, with the most robust evidence demonstrated for combined paclitaxel and ramucirumab (table 1c). This combination has demonstrated a benefit in both survival and also in quality of life.

Further lines

Further lines can be considered in fit patients (PS 0–1). Third lines with taxanes or irinotecan (depending on the second line) are acceptable, despite a lack of clear evidence. Trifluridine/tipiracil will likely be considered in the near future due to the benefit shown in a phase III clinical trial.17

Innovative strategies

The GC treatment paradigm may change in the near future. Recognition of the historic failure in molecular selection due to GC heterogeneity was an important first step. Liquid biopsies should help us to acquire important biomarker information.18 Moreover, and taking into account the underlying gastritis that normally precedes GC tumorigenesis, the encouraging results showed by immune checkpoint inhibitors in the refractory setting19 will hopefully be translated into the clinical setting from the ongoing phase III clinical trials, with a consequent significant improvement in the prognosis of patients with GC.

In GC tumours with microsatellite instability, pembrolizumab, although not approved by the Europena Medicines Agency, may be recommended, as well as in refractory programmed death-ligand 1-positive (combined positive score) patients.19 In the Asian population, nivolumab has shown OS benefit in this refractory setting.20

Conclusions

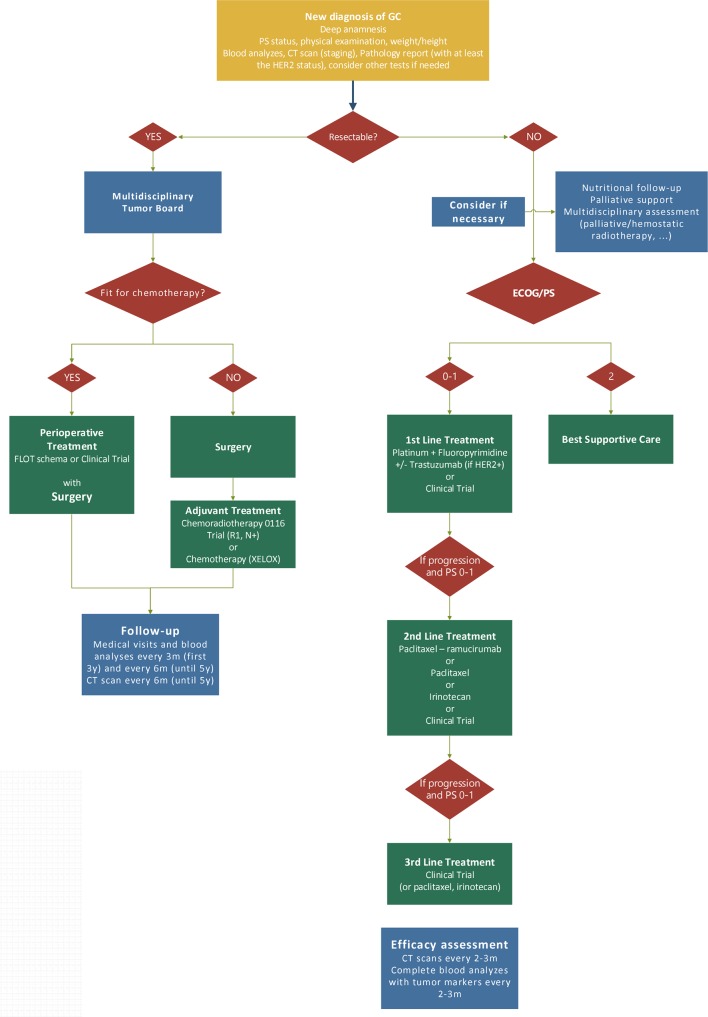

Patients with GC should be discussed in multidisciplinary tumour boards. The particular fragility of these patients requires close monitoring by multiple specialists including nutritionists and supportive care professionals. Moreover, given the molecular complexity of these tumours, careful hierarchy when selecting a targeted treatment should be considered. Having established the standard practice in the clinic (figure 1), physicians should always consider a clinical trial as the first option to offer.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the treatment of GC. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FLOT, fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, docetaxel; GC, gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancer; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PS, performance status.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MA reports personal financial interest in form of scientific consultancy role for BMS, Servier and MSD. She has received honorarium for speaking issues from MSD, BMS, Lilly, Roche and Amgen; and has had travel expenses partially covered by Roche, Amgen and Lilly. JMM does not report personal financial interest. MD has received travel expenses partially covered by Ipsen, Lilly and Servier. SC reports personal financial interest in form of honorarium for speaking issues or travel expenses from Johnson&Johnson, Wyeth, Covidien and Roche. JT reports personal financial interest in form of scientific consultancy role for Array Biopharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Genentech, Genmab A/S, Halozyme, Imugene Limited, Inflection Biosciences Limited, Ipsen, Kura Oncology, Lilly, MSD, Menarini, Merck Serono, Merrimack, Merus, Molecular Partners, Novartis, Peptomyc, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, ProteoDesign SL, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi, SeaGen, Seattle Genetics, Servier, Symphogen, Taiho, VCN Biosciences, Biocartis, Foundation Medicine, HalioDX SAS and Roche Diagnostics.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global Cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2016;27(suppl 5):v38–49. 10.1093/annonc/mdw350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass AJ, Thorsson V, Shmulevich I, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014;513:202–9. 10.1038/nature13480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosman FT, et al. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Vol. 3 IARC WHO Classification of Tumours: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edge SB, Compton CCJAoso. The American Joint Committee on cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM, 2010: 1471–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa055531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon J-P, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. JCO 2011;29:1715–21. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuhmacher C, Gretschel S, Lordick F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for locally advanced cancer of the stomach and cardia: European Organisation for research and treatment of cancer randomized trial 40954. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:5210–8. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. The Lancet 2019;393:1948–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Haller DG, et al. Updated analysis of SWOG-directed intergroup study 0116: a phase III trial of adjuvant radiochemotherapy versus observation after curative gastric cancer resection. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2327–33. 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dikken JL, Jansen EPM, Cats A, et al. Impact of the extent of surgery and postoperative chemoradiotherapy on recurrence patterns in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2430–6. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiekema J, Trip AK, Jansen EPM, et al. The prognostic significance of an R1 resection in gastric cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:1107–14. 10.1245/s10434-013-3397-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cats A, Jansen EPM, van Grieken NCT, et al. Chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy after surgery and preoperative chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer (critics): an international, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:616–28. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30132-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bang Y-J, Kim Y-W, Yang H-K, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (classic): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:315–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61873-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner AD, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4991–7. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shitara K, Doi T, Dvorkin M, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil versus placebo in patients with heavily pretreated metastatic gastric cancer (tags): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1437–48. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30739-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pectasides E, Stachler MD, Derks S, et al. Genomic heterogeneity as a barrier to precision medicine in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2018;8:37–48. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e180013 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang Y-K, Boku N, Satoh T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:2461–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]