Abstract

Objective:

Though sparse in previous years, research on the mental health of Black men has recently experienced a gradual increase in social work journals. This article systematically organizes and critically examines peer-reviewed, social work evidence on the mental health of Black men.

Methods:

Twenty-two peer-reviewed articles from social work journals were examined based on their contribution to social work research and practice on the mental health of Black men.

Results:

The social work evidence on Black men’s mental health can be grouped into one of four categories: psychosocial factors; mental health care and the role of clinicians; fatherhood; and sexual orientation, HIV status, and sexual practices.

Conclusions:

This representation of the social work literature on Black men’s mental health neglects critical areas germane to social work research and practice with this population. Implications include ways to extend current social work research and practice to improve the health for Black men.

Keywords: Black/African American men, mental health, review, social work research

Black men in the United States face a disproportionate burden of preventable morbidity and mortality rates compared to other groups. Of all the health concerns faced by Black men, mental health challenges may be among the most stigmatized (Holden, McGregor, Blanks, & Mahaffey, 2012; Watkins & Jefferson, 2013). Research suggests that Black men have more adverse life experiences than men of other racial/ethnic groups, and consequently, experience poorer mental health (Watkins, 2012; Williams, 2003). Although social workers are uniquely positioned to promote mental health care for Black men, there is limited scientific evidence on concerted efforts to do so. For instance, it has been only recently that peer-reviewed social work research has highlighted the distinctive mental health needs of Black and/or African American men (Miller & Bennett, 2011). A critical examination of empirical social work evidence on the mental health of Black men is necessary to understand the gaps in knowledge and practice, which exist for this already underserved population. The purpose of this article is to systematically organize and critically examine social work evidence on Black men’s mental health.

When Research on Social Work Practice (RSWP) published its special issue in 2011 on the challenges, disparities, and experiences of African American men, it was a remarkable move toward the discipline’s previous meager efforts in addressing the health and social concerns of Black and/or African American men. Guest edited by Miller and Bennett (2011), this special issue presented evidence-based social work research and interventions involving racial and ethnic subgroups of Black men. The special issue included peer-reviewed articles about Black fatherhood, medical help seeking, and mental health experiences and service utilization by Black men. The publication of the RSWP special issue was appropriate for initiating the conversation about social work’s role in presenting peer-reviewed, evidence-based research about and with Black men. However, it also generated imperative questions about the role of peer-reviewed social work literature in articulating the mental health needs of Black men. Namely, is social work scholarship at the forefront of setting an agenda to build upon current knowledge and identify culturally competent solutions to improve mental health outcomes for Black men? This review attempts to answer this question by assessing the current landscape of peer-reviewed evidence on Black men’s mental health. A first step toward addressing this is to evaluate the research and practice paradigms predominately used by social workers who work with Black men.

Research on African Americans Through the Social Work Lens

Social work research on African Americans is dominated by a discourse suggesting that racial and ethnic experiences and traditions need to be incorporated into social work practice with this population in order for their living and working conditions to improve. This ethnic-centered approach to social work promises success through the use of more holistic methods, rather than theoretical, when studying and working with African Americans. For three decades, the use of Africentric (or “Afrocentric”) paradigms has been increasingly popular in the design, implementation, and evaluation of social work research and practice with African Americans (Aymer, 2010; Gilbert, Harvey, & Belgrave, 2009; Harvey, 1985, 1997; Harvey, Loughney, & Moore, 2003; Harvey & Rauch, 1997). Documented by early scholars as a way for social workers to address the totality of African Americans’ worldviews and existence, Africentric paradigms incorporate the history of oppression, culture, and loss of identity in research and intervention efforts to address problems and adverse living conditions of African Americans (Schiele, 1997).

The success of Africentric paradigms in social work practice supports Africentric approaches as evidence-based strategies that work (Gilbert et al., 2009). However, despite using these approaches when working with African Americans, infusing such paradigms and practices into social work education and research with African Americans has been limiting in two distinct ways. First, the use of ethnic-centered approaches has not been examined in the context of gender differences. For example, the ability to embrace the role of gender as an intersecting identity (i.e., what makes African American men and women different from/similar to one another) using an Africentric perspective would allow for more tailored micro- and macro-social work research and practice efforts with African Americans. Second, the use of ethnic-centered approaches has not been interrogated in the context of any particular area of social work research and practice, such as mental health. Though Africentric paradigms are used as comprehensive strategies to address varying social and psychological conditions of African Americans, the techniques applied to the mental health conditions of African Americans are not well developed.

The Role of Social Workers in the Mental Health of Black Men

A report from the National Association of Social Workers (2006) suggested that only 7% of social workers are Black or African American, and Black men (just as men of other racial/ethnic groups) tend to be underrepresented in the social work profession. Despite this, however, the social and economic circumstances of some African Americans mean that they may interface with a social service system and/or professional on a regular basis. As many African American men with fewer socioeconomic resources also shoulder a disproportionate burden of health and mental health conditions (Watkins & Neighbors, 2012; Williams, 2003), more social work consultations and interventions would be beneficial to this population. Particularly, the Black men whose lives intersect with challenges related to health and mental health care access and utilization, obtaining employment, family roles and relationships, educational attainment, trauma related to exposure to violence, and incarceration can benefit from social work (Davis, 1999; Johnson, 2010; Rasheed & Rasheed, 1999).

The role of social workers in supporting the healthy development of Black men is expansive. Yet, peer-reviewed social work in this area is difficult to acquire and consolidate. A search in Google on evidence of social work’s role in the lives of Black and/or African American men suggests this area is underdeveloped, as it generates sparse results beyond articles from news media, personal and organizational blogs, and social media sites. In addition, the Internet suggests that social work evidence with and for Black men has been grounded in books on general social work practice (Davis, 1999; Rasheed & Rasheed, 1999) and edited volumes on social work with African American men in the context of health, mental health, and social policy (Johnson, 2010). These important bodies of work have outlined the use of racial and ethnic experiences and traditions (i.e., Africentric beliefs) in social work practice, the role of public and private institutions in the health and well-being of Black men, how improvements in policy can also improve the living and working conditions of Black men, and the evidence-based social work efforts geared toward Black men. Despite these contributions, the discipline still lacks affirmation that peer-reviewed, social work evidence on the mental health of Black men has been actively developed, disseminated, and has evolved concurrently with the scholarship on health, psychological functioning, and masculine identity for Black men (Cooper, 2006; Nickleberry & Coleman, 2012; Pierre, Mahalik, & Woodland, 2001; Watkins, 2012; Watkins, Walker, & Griffith, 2010).

Mental health, in the context of the deleterious historical experiences of Black men, has been well documented in the literature (Jackson et al., 1996; Pierre & Mahalik, 2005; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011). These challenges, as well as stigma, fear, and distrust, are barriers that can deter African Americans, particularly men, from engaging in research and therapeutic services provided by social workers (Boyd-Franklin, 2003; Johnson, 2010; Rasheed & Rasheed, 1999). The idea of using ethnic-centered approaches in social work research and practice with Black men’s mental health shows promise. However, beyond their use, a deeper understanding of previous social work research and practice on Black men and mental health is necessary. The aim of the current study was to systematically organize and critically examine the peer-reviewed, social work evidence on Black men’s mental health. Though studies on Black Americans have clearly delineated mental health differences among and between subgroups of Blacks in the United States (Joe, Baser, Breeden, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2006; Williams et al., 2007), for the purposes of this review, our definition of Black men is inclusive of all men of African descent. It is important to note that the authors of the articles included in this review oftentimes did not distinguish between varying ethnicities of their Black male samples, particularly, with regard to ethnicity, nativity, language, and other culturally specific indicators. Therefore, we discuss the articles included in this review in the context of our study aim and the ways in which the authors presented their findings.

Method

Selection Criteria and Review Procedure

Articles for this review were selected and analyzed using a four-tiered matrix method (Garrard, 2011). First, we searched databases (e.g., PsycINFO, Ebscohost, JSTOR, ProQuest, PubMed, and Google Scholar) for peer-reviewed social work articles on Black and/or African American men and mental health outcomes. Each article we found was then carefully examined with special attention given to the articles that included a disaggregated sample of African American, or Black men and one or more mental health conditions. We defined mental health conditions as any clinical or nonclinical indication of mental, emotional, or psychological outcomes discussed in the articles (i.e., anxiety, psychological distress, stress, and depression). The beginning stages of the search uncovered many articles outside of social work journals (many were located in interdisciplinary journals read by social workers), so we decided to conduct a second stage of the search that involved searching for articles about Black and/or African American men and mental health conditions with social work’ in the journal’s title. This uncovered articles that were carefully vetted, with special attention to each article’s focus on men,’ African American or Black men,’ and mental health conditions.

In hopes of locating new articles to include in the review, we conducted a new search 6 months after our initial search. This search process replicated the steps from our initial search (described previously), but then we also searched in journals with high impact factors as determined by Eigen factor and the Journal Citation Reports. Studies that reported data from other races/ethnicities were included in the review; though, only studies where the results for Black and/or African American men could be extracted were included. Bibliographies of the compiled articles were reviewed for other potential sources; and journal articles that did not focus entirely on the subject descriptors were removed from the final review. Based on our own professional experiences as researchers and practitioners working with Black men, we were surprised to find so few articles published in social work journals about the mental health conditions of African American men. As a result, our three-person team conducted an additional search where each person was responsible for reviewing seven journals each from a list of 21 of the most prominent social work and social work–related journals (developed by the lead author) and conducting a within-journal search for all articles that reported findings on Black and/or African American men and mental health conditions.

The various stages of our search rendered 32 articles. After screening for eligibility, 26 remained. The 26 articles from social work journals were then reviewed for topical area overlap, whether subgroups of Black and/or African American men were the focus, and how clearly they articulated the mental health conditions of the Black male samples. This additional screening resulted in 22 articles for the final review. If a study identified more than one mental health condition, each condition was examined for this review. If a study appeared to fall into more than one of our overarching themes, we categorized it based on the most prominent focus and/or outcome of the study.

Results

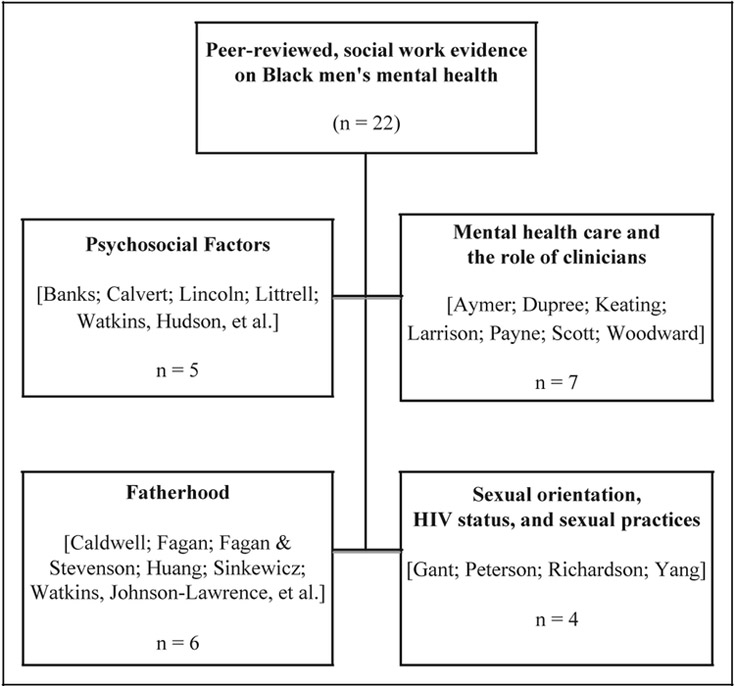

Our search uncovered 22 peer-reviewed articles published between 1995 and 2013 that met review criteria. Most (19) of these articles employed quantitative research methods that were either cross-sectional or longitudinal. One article was a qualitative study, one was a quasi-experimental report from an intervention, and an additional one was a conceptual/theoretical article. Four of the articles reported findings from the same survey, the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) and two reported findings from the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study. Three of the studies were published between 1995 and 2000, 7 of the studies were published between 2001 and 2006, and 12 of the studies were published between 2007 and 2013. Our analyses revealed four topical areas (Figure 1) that dominated the peer-reviewed, social work literature on the mental health of Black and/or African American men: (1) mental health care and the role of clinicians; (2) the influence of fathers and fatherhood; (3) psychosocial factors; and (4) sexual orientation, HIV status, and sexual practices (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Topical areas of peer-reviewed publications (by first authors’ last names) on the mental health of Black men in social work journals.

Table 1.

Topical Areas and Representative Findings of Black Men and Mental Health Reported in Peer-Reviewed Social Work Journals.

| Topical Area | Findings That Best Represent the Topic Area |

|---|---|

| Mental health care and role of clinicians in mental health | • Cultural beliefs are important in Black men’s decisions to seek care • There are variations in clinical bias versus cultural variance regarding diagnosing depression in Black men • Black men may be less likely to go to the doctor than men of other racial/ethnic groups • There are problems with how clinicians diagnose depression in Black men • Africentric principles are needed in clinical mental health interventions for Black men • There is mistrust of the mental health care system by Black men (due to fear, poor relationships between Black community, and service providers) |

| (Mental health conditions in these studies included MDD and depressive symptoms) | |

| Fatherhood and mental health | • Research focuses on residential and nonresidential Black fathers • Fathers and father figures are highlighted across the studies • Married fathers and their relationships with child(ren)’s mother(s) are underscored in a few of the studies (studies highlight importance of “spousal support” in mental health outcomes) • Differences in father figures influence mental health outcomes across men of various racial groups • Intervention with Black fathers suggest empowerment-based programs are effective among residential Black fathers |

| (Mental health conditions in these studies included self-esteem, emotional health, psychological distress [using the Kessler 6], substance use and dependence, and depressive symptoms [using the CESD]) | |

| Psychosocial factors and mental health | • Sociodemographic factors have varying influences on the mental health outcomes of Black men (studies highlight the heterogeneity among national samples of Black men) • There is a strong connection between physical health and mental health • Discrimination seems to still influence mental health outcomes for Black men (more so than for Black women) • Active, problem-focused coping (rather than emotion-focused coping) is effective for reducing depressive symptoms |

| (Mental health conditions in these studies included MDD, depressive symptoms [using CESD], psychological distress [using Kessler 6], and quality of life measures [that underscore “mentally unhealthy days”]) | |

| Sexual orientation, HIV status, sexual practices, and mental health | • Different kinds of social support (i.e., emotional, kin, and nonkin) can have varying influences on Black men of various sexual orientations • Social support is vital to the positive mental health outcomes of MSM and HIV (positive and negative) Black men |

| (Mental health conditions in these studies included depressive symptoms (measured using the CESD)) |

Note. MDD ¼ major depressive disorder; CESD ¼ Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MSM ¼ men who have sex with men.

Mental Health Care and the Role of Clinicians

The majority (n 7) of the studies examined for this review focused on mental health care and the role of clinicians in the lives of Black and/or African American men (Aymer, 2010; Dupree, Watson, & Schneider, 2005; Keating & Robertson, 2004; Larrison et al., 2004; Payne, 2012; Scott, Munson, McMillen, & Snowden, 2007; Woodward, Taylor, & Chatters, 2011). Overall, these studies analyzed either quantitative or qualitative data and generated their findings from clinical and/or community-based samples of Black and/or African American men. For example, Woodward, Taylor, and Chatters (2011) reported the kinds of formal and informal support preferred by African American men using a nationally representative sample of African American and Caribbean Black men who met criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance abuse disorder. The authors reported that about 33% of the respondents used both professional services and informal support, while 14% relied on professional services only and 24% used informal support only. Of the sample that met diagnostic criteria for a DSM disorder, 29% sought no help at all (Woodward et al., 2011).

Woodward and colleagues (2011) suggested that informal support might act as a protective factor against the development of disorders among Black men. These findings by Woodward and colleagues raised important questions about potential factors that may influence help seeking among Black men. Further, this finding was aligned with those from other studies, reporting that support from extended family, religious participation, friends, and other nonkin acquaintances may play important roles in the lives of African Americans (Chatters et al., 2008). Social and cultural factors and clinical mistrust were among the primary reasons why African American men sought and used services for mental health-related issues, according to Woodward and colleagues. Aligned with this are the findings from Scott, Munson, McMillen, and Snowden (2007), which suggested that custody status was significantly related to the participants’ (who were transitioning out of foster care) predisposition to seek mental health care. Those still in foster care reported a greater predisposition than those no longer in foster care. Resultsshowed that cultural mistrustof mental health professionals, devaluation–discrimination, and emotional control were significantly and inversely correlated with predisposition to seek mental health care. Secrecy was also a moderate, inverse correlate of one’s predisposition to seek mental health care (Scott et al., 2007).

Similar to the study by Scott et al., clinical mistrust was also a factor in the Keating and Robertson’s (2004) study, which reported findings from focus groups with 96 African American and Caribbean men and women. This study found that participants were fearful of being admitted to the hospital and believed that the use of mental health services would in some way lead to their death; a medical mistrust of the health care system that is indicative of the racial and cultural history of people of color (Keating & Robertson, 2004). In contrast to the previous findings, a study by Larrison and colleagues (2004) found that client outcomes did not differ as a function of race, gender, and age during mental health treatment. Overall, clients’ symptomatology either decreased or remained constant (depending primarily on their diagnosis) during the 9-month period of the study. The average change over time was approximately one third of a point on the 4-point scale. This change was statistically significant, though its clinical significance was not reported. The only demographic variable significantly related to variation in symptomatology patterns was diagnosis; but the kind of diagnosis participants received was not reported (Larrison et al., 2004).

The majority of the articles on mental health care and the role of clinicians focused on reports from African American male respondents; however, some included responses from the mental health care professionals who diagnosed and treated African American men (Aymer, 2010; Keating & Robertson, 2004; Payne, 2012). For instance, Aymer (2010) offered oneoffew reports that focused on strategies for working with African American men in clinical mental health and health care settings and suggested that social work practitioners consider the sociocultural context of attitudes toward seeking and accepting help among African American men. Specifically, Aymer argued for an integration of an Afrocentric approach and psychodynamic theories into clinical work that targets African American men. Use of these frameworks can help social workers consider how the issues of race, oppression, and gender impact African American men and their engagement in clinical services. Aymer argued that an essential component of working with African American men in a clinical setting is developing coping strategies for everyday stressors (i.e., racism) that are a unique environmental experience of this group.

In addition to their sample of Black service users, families, and caregivers, Keating and Robertson (2004) included a sample of professionals in their study of the “circles of fear” in Black communities, with regard to mental health care. Responses from the mental health service professionals suggested that they also experienced fear when working with Black people. This fear, according to the authors, derived from the professionals’ own perceptions of violence and danger working in Black communities. This fear translated into the professionals’ use of restraint procedures when working with Black people, as well as difficulty expressed by professionals who wanted to address race and culture when working with Black clients. Keating and Robertson stated “One can assume that, if it is not safe for professionals to talk about issues of race and culture amongst themselves, then it must be even more difficult for service users, families, and carers to talk to professionals about it” (p. 445). In a similar vein, Payne (2012) examined race and symptom expression among African American men from the perspectives of clinicians. Using video vignettes of African American and White male actors, she found that clinicians identified “classic” (i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]) symptoms of depression in African American men but not culturally expressed symptoms of depression (e.g., irritability, hostility, and less likely to verbalize depression) in African American men. Namely, the clinicians identified mood disorders less often when the African American male client displayed culturally expressed depressive symptoms.

The Influence of Fathers and Fatherhood

We found six studies in social work journals that considered the influence of fathers and fatherhood in the mental health of Black men (Caldwell, Bell, Brooks, Ward, & Jennings, 2011; Fagan, 2009; Fagan & Stevenson, 2002; Huang & Warner, 2005; Sinkewicz & Lee, 2011; Watkins, Johnson-Lawrence, & Griffith, 2011). Overall, these studies suggested that not only do relationships with family members have implications for the presence of depressive symptoms, but the quality of these relationships is related to mental health outcomes for Black men. Three of the six studies examined in this review used the Fragile Families and Child Well-being data and presented related, though different, mental health outcomes of father respondents. For instance, Huang and Warner (2005) reported that married fathers have the lowest rate of depression (6.6%), followed by cohabiting (8.7%), romantically involved (11.9%), and not involved (19.9%) fathers. Among all fathers, the quality of their relationship with the mother of their child and the fathers’ substance use problems were found to be important predictors of fathers’ depression (Huang & Warner, 2005). Although few characteristics of the sample were presented in the context of race, Huang and Warner did report that the odds of a depressive episode were 35% lower for African American and Hispanic fathers than they were for non-Hispanic White fathers.

In a related study that used the Fragile Families and Child Well-being data, Fagan (2009) found that African American fathers who reported low partner support also reported high depressive symptoms. Study findings suggested that emotional health, spousal relationships, and support are important for African American fathers. Also using the Fragile Families and Child Well-being data, Sinkewicz and Lee (2011) underscored the influence of age and marital status on Black fathers’ mental health outcomes. For instance, the authors reported that major depressive disorder was higher among Black fathers, overall, compared to the general population. Also, anxiety, substance dependence, and poor health were disproportionately higher among Black fathers, placing them at a disadvantage when dealing with their own mental health, much less in their roles as fathers. Age differences were depicted in the findings by suggesting that depression was more prevalent among younger fathers than older fathers. According to the findings by Sinkewicz and Lee, 5% of married fathers, compared with almost 30% of fathers who were friends or less than friends with the mother of their child, reported depression. As for educational differences, fathers with less than a high school diploma were twice as likely to report depression (23.6%) compared to those with a high school diploma. In other words, very little depression was reported by fathers who had more than a high school education (Sinkewicz & Lee, 2011).

Education was also a predictor for parenting practices and mental health outcomes of nonresident, African American fathers in the study by Caldwell, Bell, Brooks, Ward, and Jennings (2011). The authors found that fathers who were younger, had more education, and were engaged in race-related socialization behaviors, monitored their sons more than fathers who did not report these characteristics. Also, nonresident fathers with fewer depressive symptoms monitored their sons more frequently than those with more depressive symptoms, overall (Caldwell et al., 2011). Parenting practices were also assessed in Fagan and Stevenson’s (2002) study that examined self-esteem, selfperceptions of parenting, and racial socialization outcomes for fathers and father figures who participated in the Men as Teachers intervention. Their findings underscored the importance of empowerment-based programs for helping fathers to feel more competent as facilitators of their children’s teaching–learning experiences. The authors could not confirm that the intervention led to more positive interactions between fathers and their children; however, the intervention was associated with improved parenting satisfaction and self-esteem among resident African American fathers, but not for nonresident African American fathers.

Similar to the Fagan and Stevenson study, the study by Watkins, Johnson-Lawrence, and Griffith (2011) also focused on the influence of father figures, as it included disaggregated racial and ethnic differences on mental health outcomes using a nationally representative sample of African American, Caribbean Black, and non-Hispanic White men. The authors reported that, compared to non-Hispanic White men, being raised by a grandfather placed African American and Caribbean Black men at higher risk for depressive symptoms and psychological distress under certain demographic conditions. The authors expressed the limitations of their cross-sectional findings, as their model retrospectively examined the influence of father figures. They concluded that when it comes to the mental health and well-being of African American men as adults, the presence of a father figure during their youth may be less important than the presence or absence of other socio-demographic factors (Watkins et al., 2011).

Psychosocial Factors

Five of the studies examined for this review focused on some aspect of mental health outcomes for Black and/or African American men as determined by psychosocial factors (Banks, Kohn-Wood, & Spencer, 2006; Calvert, Issac, & Johnson, 2012; Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins, & Chatters, 2011; Littrell & Beck, 2001; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011). These studies were more likely than not to either discuss psychosocial factors as stressors or protective factors for Black men. All of the studies that reported outcomes for psychosocial factors as stressors for Black men were quantitative and sampled from various subgroups of Black men (i.e., nationally representative samples, multistage probability samples, and community-based samples). Our review of the studies under this topical area suggested that psychosocial factors can exacerbate depressive symptoms and mood disorders for Black men (Banks et al., 2006; Calvert et al., 2012; Lincoln et al., 2011; Littrell & Beck, 2001; Watkins et al., 2011). Specifically, the studies led by Lincoln and Watkins used the same, nationally representative data set to report on how sociodemographic characteristics and psychosocial factors (i.e., mastery and discrimination in the study by Watkins) influence depressive symptoms, psychological distress, and 12-month and lifetime major depressive disorder by age for African American men. Lincoln and colleagues found that marital status and region were statistically significant with lifetime major depressive disorder for African American men and underscored the heterogeneity of African American men in their conclusions. Disaggregating the differences across age-linked life stages, Watkins and colleagues found that discrimination predicted depressive symptoms for African American men ages 35 to 54, and that across all groups, as mastery increased, major depressive disorder decreased.

The study by Banks, Kohn-Wood, and Spencer (2006) compared the experiences of everyday discrimination for Black men and women using the 1995 Detroit Area Study. The authors found that Black men reported more perceived discrimination than Black women (who reported more anxiety symptoms compared to Black men), though neither group reported differences in depressive symptoms. Also noteworthy is that the authors suggested that considering gender in their interpretation of the anxiety symptoms is important, as the Black men’s experiences with major life events—such as a major illness or being victimized—was the only variable that was statistically associated with anxiety symptoms for Black men. Also in the context of major life situations, Littrell and Beck’s (2001) study of African American homeless men suggested that active, problem-focused coping (rather than emotion-focused coping) reduced depressive symptoms among the sample. Taking into consideration the level of psychosocial stressors that can influence the mental health outcomes of African American men, the authors highlighted the variations in how chronic stressors serve as a backdrop for more discrete stressors that may or may not influence depressive symptoms. Their sample of problem-focused copers who experienced fewer depressive symptoms than emotion-focused copers raises questions about the degree to which masculine gender norms (and adherence to these norms) should be taken into consideration when engaging in social work research and practice with Black men. Considering the psychosocial susceptibility of Black men is essential to the discourse about how their mental health and overall well-being can be improved. Unexpectedly, only one study in this review addressed the quality of life of Black men and included both mental and physical health indicators. Calvert, Issac, and Johnson (2012) examined the quality of life for Black men, though the number of mentally unhealthy days was included as an outcome of the study. Specifically, the authors reported that the number of mentally unhealthy days was 4 times higher for Black men in their study compared to what has been reported in Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System studies (Calvert et al., 2012).

Sexual Orientation, HIV Status, and Sexual Practices

Four articles discussed the mental health outcomes of Black men in the context of their sexual orientation, HIV status, and sexual practices (Gant & Ostrow, 1995; Peterson, Folkman, & Bakeman, 1996; Richardson, Myers, Bing, & Satz, 1997; Yang, Latkin, Tobin, Patterson, & Spikes, 2013). Noteworthy about this topical area was how three of the four articles retrieved were published in the mid- to late 1990s, which may indicate a gap in the social work scholarship in this topical area (though one of the four studies was published in 2013). Three of the four studies also focused on social support as a predictor of mental health outcomes for men. For example, Gant and Ostrow (1995) examined a sample of White and African American men with HIV and found no significant correlations between support and general mental health (included depression, loneliness, and profile of mood) among the African American men. Also, given the literature on the importance of family support of African Americans’ health (Ford, Tilley, & McDonald, 1998; McDonald, Wykle, Misra, Suwonnaroop, & Burant, 2002), the authors expressed disbelief in finding that most of the mental health outcomes of their study (tension/anxiety, anger/hostility, and loneliness) were not related to (or the result of) material social support from family. The association between material social support and depression (measured using the Beck Depression Inventory) was the only exception.

Social support was also the focus of Peterson, Folkman, and Bakeman’s (1996) study of 139 African American men who identified as gay, bisexual, or heterosexual. In addition to depressive symptoms, the authors assessed psychosocial coping resources, including social support, optimism, and religiosity/spirituality. Results suggested that psychosocial resources can help to mediate effects of stressors, including physical health, hassles, and life events, on depressed mood. The most frequently reported hassle among the sample of African American men was having enough money. HIV serostatus (defined as the seropositive or seronegative status to an antibody, i.e., HIV) was not associated with depressed mood, but a positive association was found between physical and mental health. Also noteworthy was that sexual orientation was not associated with depressed mood, but social support had a strong association with depressed mood. Similarly, in their study of 311 seronegative African American men (who were at risk for HIV), Richardson, Myers, Bing, and Satz (1997) found that current mood disorders were predicted by age and heavy cocaine use by the respondents. Current anxiety disorders were predicted by gay/bisexual orientation and acute exposure to drugs other than cocaine (Richardson et al., 1997). The early studies published on Black men’s sexual orientation, HIV status, and mental health outcomes provide a backdrop for the more recent study published by Yang, Latkin, Tobin, Patterson, and Spikes (2013), which found that emotional support from family members or sexual partners decreased the odds of experiencing depression among a sample of 188 African American men who have sex with men. Receiving financial support from family and friends increased respondents’ odds of experiencing depressive symptoms, and despite the availability of their family members, respondents relied heavily on support from nonkin (Yang et al., 2013).

Discussion

Social science literature suggests that persistent exposure of Black men to innumerable stressors increases their susceptibility to poor mental health outcomes (Watkins, 2012; Watkins, Green, Rivers, & Rowell, 2006; Watkins & Neighbors, 2012; Williams, 2003). Therefore, it is vital for peer-reviewed, social work evidence to have a place in the examination of the risk factors associated with these outcomes. Since mental health is an ineffaceable component of overall health, well-being, and social justice, social work’s ability to address the mental health needs of Black men requires a critical examination of factors that affect their living and working conditions. This review sought to systematically examine the published research and social work practice literature on the mental health of Black men. Our definition of the term “mental health” was broad, in that we included clinical reports as well as communitybased reports on various mental health and well-being outcomes. We also sought to identify the gaps in the literature, so that we could propose next steps for improving social work research and practice on Black men and mental health. The findings from this review are important because they extend the work of previous social work scholars whose efforts have been necessary for addressing the “invisible presence” of Black men in social work research, policy, and practice (Davis, 1999; Johnson, 2010; Rasheed & Rasheed, 1999). Though, the findings from this review are particularly noteworthy because they provide an 18 year scope of (1) what topics have dominated (as well as those that have been excluded from) the social work scholarship on Black men and mental health, (2) the types of data and data sets that have helped shape what we know about Black men and mental health, and (3) the implications for future investigations and social work efforts that must be made to improve the mental health of Black men.

Dominant Discourse on Black Men’s Mental Health

Our review retrieved 22 articles that clustered around four topical areas of social work evidence on the mental health of Black men: mental health care, fatherhood, psychosocial factors, and sexual orientation. Though these topics initiate deeper inquiry into this area, the representations of Black men’s mental health displayed by these topical areas neglect a number of other critical areas germane to social work research and practice with this subgroup of men. For instance, micro-social work practice issues and strategies for intervention are present and well represented in the literature; however, macro-practice issues and ways to link practice, policy, and research are absent. Furthermore, despite social work’s community presence, few studies document mental health research and evaluation in communities of Black men. Another way to think about why this is important to social work is to consider the role of the Black family in the emotional health and well-being of Black men. When a man is ill, it is difficult for him to fulfill expected obligations to his family and others in his social network. Sickness or injuries can have multiple effects on the Black family and bring about other stressful events such as marital discord, sexual difficulties, and changes in personal habits and social activities (Watkins & Neighbors, 2012). Many Black men find it difficult to fulfill their roles as providers and protectors of their families when they experience poor mental health (Watkins, 2012), which has implications for social work research and practice in Black communities and with Black men from those communities.

Though this review underscores the dominant social work evidence on Black men and mental health, it also identifies gaps in this scholarship. For example, given the increased prevalence of HIV and AIDS among underserved populations and particularly among men of color, we were surprised that we were unable to find more peer-reviewed articles in social work journals that offer social work’s position on this matter. Certainly, as social workers in the field are grappling with the challenges of their clientele, sexual orientation and HIV/AIDS status must be among the topics faced. Future social work research and practice should take this into consideration, as well as the research, practice, and policy implications of the intersection of HIV/AIDS status and mental health for Black men. For the purposes of this review, articles that included chronic diseases as outcomes were excluded as well as those with evident associations between mental health and comorbid physical health concerns (i.e., prostate cancer and hypertension). However, articles that included comorbid mental health conditions were retained for the final review. Since many Black men are likely to seek health care for physical health conditions and not mental health conditions, we acknowledge the broader need for more studies that link such physical health and chronic illnesses to the mental health outcomes of Black men.

Evidence Aligned by Data Source and Type

Four of the articles from this review reported findings from the same survey; the NSAL, and another two used the Fragile Families and Child Well-being data. Since one third of the studies reviewed here made use of these two large, nationally representative data sets, it is important to acknowledge that the use of these two studies have largely informed what we know about the state of Black men’s mental health. The NSAL is the largest mental health study to date that uses a nationally representative sample of African Americanand Caribbean Blackmen and women (Jackson et al., 2004). The release of these data has provided a wealth of information about epidemiologic and community-level mental health, as well as how these mental health outcomes are influenced by psychosocial, physical, and environmental factors. Given the large sample of Black men (African Americans and Caribbean Blacks) from the NSAL, social workers can translate the findings into practical and policy applications.

The Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study followed a cohort of nearly 5,000 children born in large U.S. cities between 1998 and 2000 (roughly three quarters of whom were born to unmarried parents). The principal investigators of the study noted that they refer to unmarried parents and their children as “fragile families” in order to underscore that they are families and that they are at greater risk of breaking up and living in poverty than more traditional families (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001). The core study was designed to address four questions of interest to researchers and policy makers: (1) What are the conditions and capabilities of unmarried parents, especially fathers? (2) What is the nature of the relationships between unmarried parents? (3) How do children born into these families fare? and (4) How do policies and environmental conditions affect families and children? Since one third of the articles examined for this review were about fatherhood and the role of fathers in mental health outcomes, the Fragile Families and Child Well-being data provide a reliable context through which the experiences of Black fathers and their children can be understood. It will be important for future social work researchers and practitioners to continue to make use of public, nationally representative data sets to frame mental health transitions and trajectories in the context of the living and working conditions of Black men.

Implications for Social Work Research and Practice

Social workers are oftentimes the first line of defense for marginalized individuals who are faced with physical, psychosocial, or socioeconomic challenges. Future social work efforts are needed to provide a closer look at the role of Black men in the context of Black families, and how this context can leverage individual and community-level interventions that result in positive mental health outcomes for Black men. Several articles in this review included a section that discussed the implications of the study’s findings for social work research and/or practice. This is noteworthy because in order to truly make an impact on the mental health problems that affect Black men, a translational process needs to occur—specifically, mechanisms through which research is translated into practice. For instance, an important conclusion from the Calvert study was that the definition of health for Black men may not include “mental” health and that there is a need for social workers to be equipped to address co-occurring mental and physical health needs of Black men to improve their overall quality of life (Calvert et al., 2012). Mental health as it coexists with physical health conditions like prostate cancer was excluded from this review because it was beyond the scope of this stage of our work. However, there are obvious social work implications for the diagnosis and treatment ofco-occurringmentaland physical health conditions. Another important aspect of this work with regard to social work research and practice is the discipline’s adoption and incorporation of the study of men and masculinities (Coston & Kimmel, 2012; Nickleberry & Coleman, 2012) in futurework with Black men. Similarly, social workers shouldalso have knowledge of conceptual frameworks that consider varying aspects of privilege and oppression, such as intersectionality (Bilge, 2009), in their work with Black men and mental health. Interdisciplinary collaborations will also improve the ways in which social workers build on their current knowledge and move toward improving the mental health conditions of Black men. Since other disciplines, such as public health and nursing have made concerted efforts to focus on the mental health needs of Black men and improve their overall health (Bryant-Bedell & Waite, 2010; Hammond, 2012); it would behoove social workers to think about their roles in cross-discipline collaborations to address the mental health needs of Black men.

Study Limitations

Scholars who publish in social work journals are beginning to dissect the associations among social determinants and how they negatively impact Black men’s mental health using community, multistage area, and clinical settings. Our review is positioned to raise awareness of the role of social work in the mental health of Black men. However, it is not without its limitations. First, though our search for articles on the mental health of Black men in social work and social work–related journals was extensive, we were surprised to only uncover a little over 20 articles that met our review criteria. We know that given the interdisciplinary nature of social work, many social work scholars choose to submit their work to peer-reviewed journals in other disciplines. Based on the findings from our review, the implications of these decisions are important to how the topic of Black men and mental health is represented in social work and how future efforts are crafted. We are vigilant of the motivation behind why a social worker may choose to publish his or her work in another discipline’s journal. For example, decisions around receiving a timely review (given the pressures of academic promotion), being able to submit one’s work using an online manuscript submission portal (which is cost-efficient and convenient), and the audience for which the work was written (potential community stakeholders vs. academic audiences) may mean that social work scholars and those who desire to publish in social work journals may choose from a list of non-social work journals as outlets for their work. Thereby, we recognize that the articles we examined may not be representative of the scholarship performed and inspired by social workers.

Second, because few studies published in social work journals address the mental health of Black men, this review presents data from a limited number of resources. For example, this review included Black men of all ages because there is a dearth of literature on subpopulations of Black men (i.e., adolescents, college men, and older men) and mental health. The ages from this review ranged from adolescents to older men, with no attention focused on a specific age group, thus not acknowledging the possible differences in mental health conditions that may affect one group over another and over the life course. Finally, we acknowledge that due toour limitedsearchcriteria, and the fact that wesearched for peer-reviewed articles in academic databases, we have likely excluded the work of our colleagues who do not publish in academic outlets. For example, there may be social work efforts that focus on the mental health of Black men published in non-peer-reviewed journals and other non-academic outlets. Given the criteria of our review, such work was excluded. Thereby, though our review is representative of the peer-reviewed evidence on Black men’s mental health in socialwork, itmay not be representative of other social work resources on Black men’s mental health.

Conclusion

This review presents the current state of peer-reviewed, social work research on Black men’s mental health. It also identifies future areas of inquiry and the gaps in social work knowledge concerning Black men’s mental health needs. Given the ongoing stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment in underserved communities, future studies should extend current social work research and practice to improve the living and working conditions—along with access to quality mental health care—for Black men. Although researchers are making progress toward identifying many of the problems that plague Black men, efforts are few and sporadic. The lack of focus by social work scholars on the plight of Black men (particularly regarding matters that influence their mental health) results in the further marginalization of this group’s experiences and significance. Therefore, social workers must continue to synthesize what is known about the mental health of Black men and use this information in social work education, research, and practice with and for Black men. Approaches such as these will illuminate a topic that has been burdened with stigma and misapprehension and will also move researchers and practitioners toward improving the health of Black men. This literature review addresses a topic that has yet to develop a strong “voice” in the field of social work. Rather, the topic of Black men’s mental health is more like a whisper that has gradually developed momentum, as evident by the growing peer-reviewed literature between 1995 and 2013. Our hope is that this review, as well as the future efforts of our colleagues, will escalate the current whisper to a stronger voice in social work.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: Support for this work was provided in part by a pilot grant awarded to Dr. Watkins by the Sisters Fund for Global Health at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan and by pilot grants awarded to Dr. Watkins and Dr. Mitchell by the Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research (5P30-AG015281).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aymer SR (2010). Clinical practice with African American men: What to consider and what to do. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 80, 20–34. doi: 10.1080/00377310903504908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, & Spencer M (2006). An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health Journal, 42, 555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilge S (2009, February). Smuggling intersectionality into the study of masculinity: Some methodological challenges Paper presented at Feminist Research Methods: An International Conference, University of Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N (2003). Race, class, and poverty In Walsh F (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ed., pp. 260–279). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Bedell K, & Waite R (2010). Understanding major depressive disorder among middle-aged African American men. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 2050–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Bell L, Brooks CL, Ward JD, & Jennings C (2011). Engaging nonresident African American fathers in intervention research: What practitioners should know about parental monitoring in nonresident families. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 298–307. doi: 10.1177/1049731510382923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert WJ, Isaac EP, & Johnson S (2012). Health-related quality of life and health-promoting behaviors in Black men. Health & Social Work, 37, 19–27. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hls001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Bullard KM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2008). Religious participation and DSM-IV disorders among older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 16, 957–965. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181898081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper FR (2006). Against bipolar Black masculinity: Intersectionality, assimilation, identity performance and hierarchy. University of California-Davis Law Review, 39, 853–906. [Google Scholar]

- Coston BM, & Kimmel M (2012). Seeing privilege where it isn’t: Marginalized masculinities and the intersectionality of privilege. Journal of Social Issues, 68, 97–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01738.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LE (Ed). (1999). Working with African American males: A guide to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dupree LW, Watson MA, & Schneider MG (2005). Preferences for mental health care: A comparison of older African Americans and older Caucasians. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 24, 196–210. doi: 10.1177/0733464804272100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J (2009). Relationship quality and changes in depressive symptoms among urban, married African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites. Family Relations, 58, 259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00551.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, & Stevenson HC (2002). An experimental study of an empowerment–based intervention for African American head start fathers. Family Relations, 51, 191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00191.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ME, Tilley BC, & McDonald PE (1998). Social support among African-American adults with diabetes, part 2: A review. Journal of the National Medical Association, 90, 425–432. doi:PMC2608356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant LM, & Ostrow DG (1995). Perceptions of social support and psychological adaptation to sexually acquired HIV among White and African American men. Social Work, 40, 215–224. doi: 10.1093/sw/40.2.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J (2011). Health sciences literature reviews made easy: The matrix method. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DJ, Harvey AR, & Belgrave FZ (2009). Advancing the Africentric paradigm shift discourse: Building toward evidence-based Africentric interventions in social work practice with African Americans. Social work, 54, 243–252. doi: 10.1093/sw/54.3.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP (2012). “Taking it like a man!”: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health, 102, S232–S241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AR (Ed.). (1985). The Black family: An Afrocentric perspective. New York, NY: United Church of Christ, Commission for Racial Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A (1997). Group work with African-American youth in the criminal justice system: A culturally competent model In Grief GL & Ephross RH (Eds.), Group work with populations at risk (pp. 160–174). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AR, Loughney GK, & Moore J (2003). A model program for African American children in the foster care system. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 16, 195–206. doi: 10.1300/J045v16n01_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AR, & Rauch JB (1997). A comprehensive Afrocentric rites of passage program for Black male adolescents. Health and Social Work, 22, 30–37. doi: 10.1093/hsw/22.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden KB, McGregor BS, Blanks SH, & Mahaffey C (2012). Psychosocial, socio-cultural, and environmental influences on mental health help-seeking among African-American men. Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, & Warner LA (2005). Relationship characteristics and depression among fathers with newborns. Social Service Review, 79, 95–118. doi: 10.1086/426719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Brown TN, Williams DR, Torres M, Sellers SL, & Brown K (1996). Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: A thirteen year national panel study. Ethnicity & Disease, 6, 132–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, .. . Williams DR (2004). The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2006). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among Blacks in the United States. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 296, 2112–2123. doi: 10.1001/jama.29617.2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WE Jr., (Ed.). (2010). Social work with African American males: Health, mental health, and social policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keating F, & Robertson D (2004). Fear, black people and mental illness: A vicious circle? Health and Social Care in the Community, 12, 439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00506.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrison CR, Schoppelrey SL, Nowak MG, Brantley JF, Leonard M, Crooke D, .. . McCollum A (2004). Evaluating treatment outcomes for African American and White clients receiving treatment at a community mental health agency in the rural South. Research on Social Work Practice, 14, 137–146. doi: 10.1177/1049731503257874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Watkins DC, & Chatters L (2011). Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 278–288. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell J, & Beck E (2001). Predictors of depression in a sample of African-American homeless men: Identifying effective coping strategies given varying levels of daily stressors. Community Mental Health Journal, 37, 15–29. doi: 10.1023/A:1026588204527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PE, Wykle ML, Misra R, Suwonnaroop N, & Burant CJ (2002). Predictors of social support, acceptance, health-promoting behaviors, and glycemic control in African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association, 13, 23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, & Bennett MD (2011). Special issue: Challenges, disparities and experiences of African American males. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 265–268. doi: 10.1177/1049731510393985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. (2006). Licensed social workers in the United States, 2004: Supplement-Chapter 2 of 5: Who are licensed social workers? Washington, DC: NASW Center for Health Workforce Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Nickleberry LD, & Coleman M (2012). Exploring African American masculinities: An integrative model. Sociology Compass, 6, 897–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2012.00498.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JS (2012). Influence of race and symptom expression on clinicians’ depressive disorder identification in African American men. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 3, 162–177. doi: 10.5243/jsswr.2012.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Folkman S, & Bakeman R (1996). Stress, coping, HIV status, psychosocial resources, and depressive mood in African American gay, bisexual, and heterosexual men. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24, 461–487. doi: 10.1007/BF02506793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre MR, & Mahalik JR (2005). Examining African self-consciousness and Black racial identity as predictors of Black men’s psychological well-being. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11, 28–40. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre MR, Woodland MH, & Mahalik JR (2001). The effects of racism, African self-consciousness and psychological functioning on Black masculinity: A historical and social adaptation framework. Journal of African American Men, 6, 19–39. doi: 10.1007/s12111-001-1006-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed JM, & Rasheed MN (1999). Social work practice with African American men: The invisible presence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23, 303–326. doi: 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MA, Myers HF, Bing EG, & Satz P (1997). Substance use and psychopathology in African American men at risk for HIV infection. Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 353–370. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiele JH (1997). The contour and meaning of Afrocentric social work. Journal of Black Studies, 27, 800–819. [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD Jr., Munson MR, McMillen JC, & Snowden LR (2007). Predisposition to seek mental health care among Black males transitioning from foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 870–882. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkewicz M, & Lee R (2011). Prevalence, comorbidity, and course of depression among Black fathers in the United States. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 289–297. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC (2012). Depression over the adult life course for African American men: Toward a framework for research and practice. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 194–210. doi: 10.1177/1557988311424072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Green BL, Rivers BM, & Rowell KL (2006). Depression and Black men: Implications for future research. The Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 3, 227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jmhg.2006.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Hudson DL, Caldwell CH, Siefert K, & Jackson JS (2011). Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 269–277. doi: 10.1177/1049731510385470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, & Jefferson SO (2013). Recommendations for the use of online social support for African American men. Psychological Services, 10, 323–332. doi: 10.1037/a0027904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Johnson-Lawrence V, & Griffith DM (2011). Men and their father figures: Exploring racial and ethnic differences in mental health outcomes. Race and Social Problems, 3, 197–211. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9051-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, & Neighbors HW (2012). Social determinants of depression and the Black male experience In Treadwell HM, Xanthos C, & Holden KB (Eds.), Social determinants of health among African-American men (pp. 39–62). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Walker RL, & Griffith DM (2010). A meta-study of Black male mental health and well-being. Journal of Black Psychology, 36, 303–330. doi: 10.1177/0095798409353756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR (2003). The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 724–731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Haile R, Gonza´lez HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, & Jackson JS (2007). The mental health of Black Caribbean immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 52–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AT, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2011). Use of professional and informal support by Black men with mental disorders. Research on Social Work Practice, 21, 328–336. doi: 10.1177/1049731510388668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Latkin C, Tobin K, Patterson J, & Spikes P (2013). Informal social support and depression among African American men who have sex with men. Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 435–445. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]