Abstract

There is growing recognition of the gap between research and practice in mental health settings, and community agencies now face significant pressure from multiple stakeholders to engage in evidence-based practices. Unfortunately, little is known about the barriers that exist among agencies involved in formal implementation efforts or their perceptions about how implementation experts can best support change. This study reports the results of a survey of 263 individuals across 32 agencies involved in a state-wide effort to increase access to an evidence-based trauma-focused treatment for children. Quantitative and qualitative results identified lack of time and secondary trauma as significant barriers to implementation and areas in which agencies desired consultation and support. Qualitative responses further suggested the importance of addressing client/structural barriers, staff turnover, and continued intervention training. Findings inform the development of a structured consultation process for community agencies focused on addressing the multiple barriers that can interfere with implementation of evidence-based treatment.

Keywords: Implementation, Dissemination, Evidence-Based Practice, Trauma, Barriers

1. Introduction

The movement to implement evidence-based treatment (EBTs) in health and behavioral health settings continues to accelerate (Practice, 2006; Rousseau & Gunia, 2016), in part fueled by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and its push towards higher quality and more efficient patient care (Mechanic, 2012). There are now hundreds of EBTs listed on an increasing number of EBT registries (Burkhardt et al., 2015). Unfortunately, traditional methods of dissemination (e.g. conferences, continuing education workshops) do not result in effective implementation and the vast majority of children with behavioral health conditions still do not receive evidence-based treatments (Backer, Liberman, & Kuehnel, 1986; Kazdin, 2008; Satcher, 2000; Stirman, Crits-Christoph, & DeRubeis, 2004). The field of implementation science has emerged over the past decade to improve methods of transporting EBTs into practice settings (Proctor et al., 2009). Use of formal implementation approaches that target organizations have been shown to create climates more conducive to successful implementation, as well as actually improve treatment outcomes above and beyond what is obtained through dissemination alone (Glisson et al., 2012; Glisson, Hemmelgarn, Green, & Williams, 2013). For example, there has been an increase in the use of more intensive implementation strategies such as Breakthrough Series Collaboratives (BSC) or Learning Collaboratives in children’s behavioral health, and particularly for trauma-focused EBTs (Bartlett et al., 2016; Hoagwood et al., 2014; Hoover et al., 2018; Lang et al. 2015; Nadeem et al., 2014). While these approaches show promise for improving EBT implementation, less is known about barriers to implementation and especially about ongoing needs for consultation following initial implementation efforts.

A number of studies have examined barriers to EBT implementation. In early research, clinicians expressed concern about the rigidity of manualized treatments, their effect on therapeutic alliance, and applicability to their clients (Addis, Wade, & Hatgis, 1999). Subsequently, this line of research evolved with the field of implementation science. Aarons et al. (2009) used concept mapping to code interviews from 31 people, mostly administrators, about barriers and facilitators to EBT implementation. They found that cost was the most important and least changeable factor. Beidas et al. (2016) interviewed 56 people, mostly agency and state leaders, and found that inner context (e.g. agency) and outer context (e.g. system/state) factors were the most frequently identified barriers to implementation. Langley et al. (2010) interviewed 35 people (27 clinicians and 9 administrators) and found that all reported similar barriers, but those with a network of other clinicians delivering the intervention and administrative support had the most effective implementation.

Palinkas et al. (2017) conducted interviews with 75 agency leaders of child/adolescent mental health clinics and found that financial costs, capacity and acceptability were perceived as the largest barriers to adoption of new evidence-based practices. Other barriers have been identified that are common to many EBTs, such as a lack of time or supervision, absence of necessary infrastructure or resources and clinician beliefs about EBTs (Aarons, 2004; Aarons & Palinkas, 2007; Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001).

Most of the existing research on barriers to EBT implementation is based on a relatively small number of qualitative interviews, and predominantly with administrators who were not necessarily active practitioners. Little is known about the different perceptions of barriers to implementation based on staff role. The present study provides quantitative data from a larger, diverse sample of clinicians, clinical supervisors, agency leaders and other staff about barriers to implementation. We also sought to identify the ongoing consultation needs of these staff, which may be different from the perceived barriers to implementation. Finally, we sought to include questions specific to the needs of clinicians implementing a trauma-focused EBT, such as addressing secondary traumatic stress. There have been previous efforts to characterize implementation barriers to EBTs in general (Harvey & Gumport, 2015) and trauma-specific interventions among adults (McLean & Foa, 2013), we are aware of only one previous empirical study (Langley et al., 2010) examining barriers specific to implementation of treatment for child trauma and this focused specifically on mental health treatment in school settings.

1.1. Current Study

The present study was designed to assess perceptions of barriers to the implementation and sustainment of a trauma-focused EBT and the desired focus of ongoing implementation consultation efforts (e.g. Trauma- Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy [TF-CBT]; Cohen, Mannarino, Berliner, & Deblinger, 2000; de Arellano et al., 2014), primarily among staff members of community-based mental health agencies that had participated in a BSC designed to facilitate TF-CBT implementation. As part of the BSC, sites were involved in an intensive implementation process over approximately one year. Agencies assembled an implementation team with staff from diverse roles, were required to participate in multiple in-person trainings and received ongoing consultation. Quality improvement initiatives were undertaken throughout this time using site-specific organizational data. Consultation also emphasized organizational factors and sustainability. Specifically, we sought to assess providers’ perspectives about 1) what were the most significant barriers to implementation; and 2) what were the most important needs for additional consultation to support implementation. Given previous literature on this topic has typically examined individuals with different roles (clinicians, administrators, etc.) separately, we also conducted exploratory analyses to examine differences in these perceptions as a function of participant role.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

At the time the survey was conducted, a total of 32 community agencies were involved in the TF-CBT initiative. The overwhelming majority of these agencies (n = 30) were participants in a BSC model and subsequent ongoing implementation support that occurred as part of a statewide EBT dissemination and implementation initiative in [STATE BLINDED FOR REVIEW] (CITATION BLINDED FOR REVIEW).

Two additional agencies initially implemented TF-CBT when a formal BSC was not available. These agencies received training, consultation and support throughout the initial implementation process comparable to what was provided through the BSC and also participated in the statewide network of TF-CBT providers alongside BSC agencies. Data were collected as part of an ongoing quality improvement initiative by the statewide Support Center (CITATION BLINDED FOR REVIEW); the initiative was deemed exempt by the [BLINDED] Department of Children and Families Institutional Review Board. Agencies varied widely with regards to size (ranging from small independent practices to large outpatient clinics) and scope of clinical practice (i.e. solely mental health vs. mental and physical health). In all but one case (residential facility), TF-CBT services were provided via outpatient treatment, where services were reimbursed by Medicaid and/or private insurance. Any agency staff member who was directly involved with the TF-CBT implementation effort at the time of the survey was eligible for participation (438 individuals). Staff were primarily clinicians, clinical supervisors, senior leaders [agency administrators such as program directors], and TF-CBT site coordinators. Coordinators served as the primary agency contact for the implementation center, and provided on-site technical and logistical support to clinicians and other staff involved in the project. Most were senior clinicians or clinical supervisors who took on additional administrative responsibilities to support TF-CBT in their agency. All agencies participating in the implementation initiative were eligible for inclusion regardless of how long they had been involved in the initiative and associated consultations. At the time of the survey, agencies had been participating in the implementation initiative for an average of 46.8 months (SD = 30.2, Range: 3–88). As the size of implementation teams varied across agencies, so did the number of individuals eligible for inclusion at each agency (M = 13.7; SD = 6.4; Range: 5–30). A total of 263 individuals completed the survey. Response rates varied significantly across agencies (Range: 28.6% - 92.9%; Overall Response Rate = 60.1%). The average number of responses per agency was 8.2 (SD = 3.9) and the average number of eligible potential respondents per agency was 13.7 (SD = 6.4). At least two complete responses were obtained from every agency.

2.2. Survey Procedures

All potentially eligible participants were invited by email to complete the survey for quality improvement purposes as part of the state implementation initiative. Senior leaders at each site were also contacted directly and encouraged to remind their staff to complete the survey. Survey responses were anonymous. Surveys were completed online via the SurveyGizmo website (Widgix, LLC; Boulder, CO). Responses were obtained over a 3-week period. After the initial invitation, periodic reminders were sent to participants who had not yet completed the survey until a response was obtained or the survey was closed.

2.3. Survey Contents

Respondents reported their role(s) on the project by selecting from the following non-exclusive options: Clinician, Clinical Supervisor, Coordinator, Data Entry Specialist, Senior Leader, Other. Participants indicated how long they had been employed by the agency, how long they had been involved with TF-CBT at the agency and the extent of their experience with TF-CBT prior to their involvement in the current implementation effort (1 = No Experience; 5 = Substantial Experience). The central focus of the present report is on ratings of potential implementation barriers and their desired focus for ongoing consultation efforts. A list of implementation barriers and consultation topics was assembled by the authors based on established implementation science frameworks (Damschroder et al., 2009; Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, & Friedman, 2005) and discussion with the coordinating center consultants about the most common problems and topics addressed during consultation. These items were then integrated with barriers obtained through qualitative feedback from providers, referral sources, and other members of the implementation team to arrive at the final set of items. Survey participants reported the degree to which they perceived each item as a barrier to successful implementation (1 = Not at all a barrier; 5 = An extreme barrier) and the extent to which they wanted the item to serve as a focus of ongoing consultation (1 = Not at all a focus; 5 = An extreme focus). In a separate free- response section, they were also asked to identify the two greatest implementation barriers faced by their agency and the two most important topics for ongoing consultation to address. Instructions indicated these free- response items could include concerns not listed in previous items.

2.4. Data Analysis

A high proportion of participants endorsed the lowest point on the scale for primary outcomes (perceived barriers, consultation foci). Accordingly, scores were dichotomized (0 = Not at all vs. 1 = All other responses) for purposes of inferential analyses. Owing to the small number of participants with the data entry specialist role, this was collapsed into the “Other” category. Primary data analyses for this study utilized a generalized linear mixed modeling approach to account for the nesting of individuals within agency. A binomial logistic link function was specified in the analysis, with a standard formula used for calculation of intraclass correlation coefficients with binary data (Snijders, 2011). Clinician was used as the reference category for analyses examining role. Due to imbalance in the number of individuals within agencies, degrees of freedom were computed using a Satterthwaite approximation. Robust estimation of covariances was used in calculation of fixed effects. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were estimated through models that included agency as a random effect. When models were unable to achieve convergence within the mixed model framework, analysis was performed using standard logistic regression procedures.

A content analysis of qualitative responses was conducted in order to classify and organize the data according to key latent themes and concepts. Barrier/focus items served as an a priori list of potential responses used in the first coding iteration. Separate categories were then created for responses which either did not fall into one of the a priori categories or that were determined to warrant a separate category based on the detailed information and frequency of responses. All responses were then organized into categories by a single coder (JAO), discussed with the larger implementation team, and then further categorized over repeated iterations until no further categorization was possible. When an individual reported two barriers or areas of focus reflective of a single theme, these were treated as a single, collective response. Topics emerging from this coding were then analyzed for extensivity (i.e. how many participants referenced the topic). Quotes that best represented each theme were identified.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics and Preliminary Analyses

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Many participants reported having more than one role on their TF-CBT implementation team (M = 1.3, SD = 0.7, Range 1–4). Accordingly, primary role was coded using the following algorithm: Senior Leader > Coordinator > Clinical Supervisor > Clinician > Data Entry Specialist > Other. “Other” roles included clinical interns (6 cases), referral sources (1 case) or program directors/clinical coordinators (3 cases). The correlation between whether a topic was perceived as a barrier and the desire for consultation focused on the topic were statistically significant, but small-to-moderate in size (r’s = .245 - .478, all p’s < .001).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | M (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Role (Non-Exclusive/Primary) | |

| Clinician (N = 200/168) | 76.0% / 63.9% |

| Clinical Supervisor (N = 51/30) | 19.4% / 11.4% |

| Coordinator (N = 27/23) | 10.3% / 8.7% |

| Senior Leader (N = 28/28) | 10.6% / 10.6% |

| Data Entry Specialist (N = 15/0) | 5.7% / 1.5% |

| Other (N = 14/14) | 5.3% / 3.8% |

| Months Employed at Agency | 60.51 (68.90) |

| Months Involved with TF-CBT at Agency | 25.42 (24.64) |

| TF-CBT Experience Prior to Current Project (1–5 scale) | 1.84 (1.07) |

Note. Non-exclusive roles reflect the percent of individuals identifying with that role independent of other roles. Thus, these add up to greater than 100%

3.2. Perceived Barriers

Complete descriptive information for perceived barriers is presented in Figure 1. Time limitations was rated as the most significant barrier, followed by secondary traumatic stress. Other particularly problematic barriers related to logistics (collaboration with referral sources) and quality improvement efforts (how to utilize data, knowledge of quality improvement strategies).

Figure 1.

Perceived barriers to TF-CBT implementation Note. * Indicates variables for which empty models unable to converge due to Hessian matrix errors. Intraclass correlations are assumed to approximate zero. ICC = Intraclass Correlation

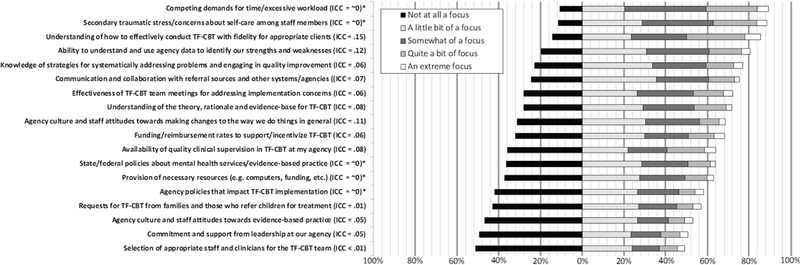

3.3. Consultation Focus

Complete descriptive information for consultation foci is presented in Figure 2. Findings largely paralleled those for perceived barriers, with respondents indicating the greatest desire for consultation focused on addressing time limitations and secondary traumatic stress. However, respondents also noted a desire for consultation focused on how to effectively conduct the treatment itself.

Figure 2.

Desired foci of ongoing TF-CBT consultation. Note. * Indicates variables for which empty models unable to converge due to Hessian matrix errors. Intraclass correlations are assumed to approximate zero. ICC = Intraclass Correlation

3.4. Effects of Role and Experience on Perceived Barriers

Odds ratios and confidence intervals for the impact of role on perceived barriers are presented in Table 2. Senior leaders were more likely to identify perceived secondary traumatic stress/concerns about clinician self-care (p = .017), knowledge of strategies for systematically addressing problems and engaging in quality improvement (p = .030), funding/reimbursement to support TF-CBT (p = .001) and state/federal policies regarding mental health services (p = .011) as barriers to implementation. Coordinators were more likely to perceive a lack of commitment and support from leadership as a barrier (p = .043). Both senior leaders (p = .005) and coordinators (p = .031) were more likely to perceive agency culture and staff attitudes towards EBTs as a barrier. Senior leaders (p = .005), coordinators (p = .007) and clinical supervisors (p = .009) were all more likely to identify selection of appropriate staff and clinicians as a barrier. Lastly, individuals identifying with the “other” role type were less likely to perceive competing demands for time/excessive workload (p < .001) or understanding of how to effectively conduct the therapy with fidelity (p = .013) as barriers.

Table 2.

Perceived barriers as a function of primary role.

|

Senior Leader |

Coordinator |

Clinical Supervisor |

Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | ||||

| Competing demands for time | 2.49 [0.31, 19.70] | 0.97 [0.21, 4.56] | 0.83 [0.22, 3.08] | 0.05 [0.02, 0.17] |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 6.04 [1.38, 26.39] | 3.10 [0.88, 10.88] | 1.28 [0.53, 3.06] | 0.35 [0.12, 1.06] |

| Communication and collaboration with referral source and systems |

1.75 [0.73, 4.21] | 0.64 [0.27, 1.54] | 1.40 [0.62, 3.18] | 0.39 [0.13, 1.21] |

| Knowledge of strategies for systematically addressing problems |

2.88 [1.11, 7.47] | 1.79 [0.70, 4.59] | 1.03 [0.47, 2.25] | 0.44 [0.14, 1.36] |

| Ability to understand and use agency data | 1.39 [0.59, 3.27] | 1.08 [0.44, 2.64] | 0.79 [0.36, 1.73] | 0.52 [0.17, 1.57] |

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards making changes | 2.27 [0.97, 5.32] | 1.67 [0.69, 4.08] | 1.86 [0.83, 4.15] | 0.43 [0.13, 1.43] |

| Funding/reimbursement rates to support/incentivize treatment |

5.26 [1.91, 14.50] | 1.78 [0.73, 4.34] | 1.31 [0.60, 2.85] | 0.64 [0.20, 1.98] |

| Understanding of how-to effectively conduct therapy with fidelity1 |

1.31 [0.57, 3.01] | 1.91 [0.75, 4.88] | 1.25 [0.56, 2.83] | 0.07 [0.01, 0.57] |

| Provision of necessary resources1 | 1.52 [0.67, 3.45] | 1.82 [0.73, 4.55] | 0.75 [0.34, 1.65] | 0.39 [0.12, 1.30] |

| Effectiveness of team meetings | 0.89 [0.39, 2.06] | 0.78 [0.32, 1.91] | 0.61 [0.27, 1.38] | 0.49 [0.15, 1.62] |

| Availability of quality clinical supervision | 1.94 [0.86, 4.41] | 1.42 [0.59, 3.42] | 1.45 [0.66, 3.20] | 0.42 [0.11, 1.58] |

| Agency policies that impact implementation1 | 0.75 [0.33, 1.73] | 1.04 [0.43, 2.52] | 1.10 [0.50, 2.44] | 0.37 [0.10, 1.38] |

| State/federal policies about mental health services | 3.03 [1.28, 7.15] | 1.52 (0.62, 3.70] | 0.55 [0.23, 1.31] | 0.25 [0.06, 1.17] |

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards evidence-based practice1 |

3.47 [1.45, 8.26] | 2.83 [1.10, 7.27] | 1.51 [0.63, 3.63] | 0.74 [0.14, 3.85] |

| Requests for treatment from families and referrals | 1.37 [0.58, 3.19] | 0.82 [0.31, 2.20] | 0.99 [0.43, 2.32] | 0.18 [0.02, 1.40] |

| Selection of appropriate staff and clinicians1 | 3.57 [1.47, 8.68] | 3.58 [1.43, 8.94] | 3.04 [1.32, 6.99] | 0.75 [0.15, 3.66] |

| Commitment and support from leadership1 | 0.82 [0.30, 2.28] | 2.67 [1.03, 6.89] | 1.03 [0.39, 2.71] | 0.85 [0.16, 4.50] |

| Understanding of the theory, rationale and evidence-base | 0.48 [0.16, 1.46] | 1.26 [0.49, 3.27] | 0.72 [0.28, 1.88] | 0.48 [0.10, 2.23] |

Notes. Clinician served as the reference group for all analyses. Bold text reflects statistically significant effects.

Indicates findings that were run as a generalized linear mixed model. All other models used logistic regression

After adjusting for role, experience (months at agency) only showed a significant relationship with one perceived barrier. More experienced clinicians were more likely to perceive funding/reimbursement incentives for TF-CBT (OR = 1.01, 95% CI [1.00, 1.01], p = .003) as a barrier to successful implementation.

3.5. Effects of Role and Experience on Desired Consultation Focus

Odds ratios and confidence intervals for the impact of role on desired consultation foci are presented in Table 3. Senior leaders were more likely to desire consultation regarding funding/reimbursement to incentivize providing treatment (p = .007). No other findings were significant.

Table 3.

Desired foci of ongoing consultation as a function of primary role.

|

Senior Leader |

Coordinator |

Clinical Supervisor |

Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | ||||

| Competing demands for time | 2.97 [0.38, 23.34] | 0.79 [0.21, 2.95] | 0.99 [0.27, 3.63] | 0.40 [0.10, 1.58] |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 3.96 [0.51, 30.72] | 1.60 [0.35, 7.32] | 1.27 [0.35, 4.57] | 0.84 [0.17, 4.04] |

| Communication and collaboration with referral source and systems |

1.11 [0.42, 2.95] | 0.72 [0.27, 1.89] | 0.79 [0.32, 1.94] | 1.74 [0.37, 8.21] |

| Knowledge of strategies for systematically addressing problems |

1.23 [0.43, 3.49] | 0.67 [0.26, 1.75] | 1.35 [0.48, 3.79] | 0.66 [0.19, 2.26] |

| Ability to understand and use agency data | 0.90 [0.34, 2.42] | 2.83 [0.63, 12.69] | 0.99 [0.37, 2.63] | 3.24 [0.41, 25.79] |

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards making changes | 1.53 [0.61, 3.83] | 1.00 [0.40, 2.51] | 2.46 [0.89, 6.82] | 1.78 [0.47, 6.74] |

| Funding/reimbursement rates to support/incentivize treatment |

7.70 [1.76, 33.67] | 2.22 [0.78, 6.28] | 1.30 [0.55, 3.06] | 2.05 [0.54, 7.76] |

| Understanding of how-to effectively conduct therapy with fidelity |

1.17 [0.37, 3.65] | 2.13 [0.47, 9.63] | 2.64 [0.59, 11.79] | 2.44 [0.30, 19.53] |

| Provision of necessary resources | 1.58 [0.65, 3.84] | 1.52 [0.59, 3.91] | 1.2 [0.52, 2.77] | 1/50 [0.44, 5.08] |

| Effectiveness of team meetings | 0.62 [0.25, 1.51] | 0.45 [0.18, 1.11] | 0.99 [0.39, 2.52] | 1.91 [0.41, 8.99] |

| Availability of quality clinical supervision | 1.42 [0.58, 3.45] | 0.98 [0.40, 2.40] | 1.42 [0.58, 3.45] | 3.14 [0.67, 14.84] |

| Agency policies that impact implementation | 0.47 [0.20, 1.07] | 0.89 [0.37, 2.14] | 1.62 [0.67, 3.92] | 0.79 [0.26, 2.47] |

| State/federal policies about mental health services | 1.99 [0.76, 5.23] | 0.93 [0.38, 2.27] | 0.92 [0.40, 2.10] | 0.95 [0.30, 3.05] |

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards evidence-based practice |

1.96 [0.83, 4.67] | 1.35 [0.56, 3.27] | 1.20 [0.54, 2.69] | 2.34 [0.69, 7.92] |

| Requests for treatment from families and referrals | 0.64 [0.28, 1.47] | 0.70 [0.29, 1.68] | 0.64 [0.29, 1.43] | 0.55 [0.18, 1.71] |

| Selection of appropriate staff and clinicians | 1.74 [0.73, 4.14] | 0.95 [0.40, 2.30] | 1.92 [0.84, 4.35] | 2.79 [0.82, 9.43] |

| Commitment and support from leadership | 0.86 [0.37, 1.97] | 1.09 [0.45, 2.62] | 0.87 [0.39, 1.94] | 3.33 [0.88, 12.57] |

| Understanding of the theory, rationale and evidence-base | 0.56 [0.24, 1.30] | 0.60 [0.24, 1.49] | 1.42 [0.53, 3.72] | --- |

Notes. Clinician served as the reference group for all analyses. Bold text reflects statistically significant effects

All analyses were run as logistic regressions. Valid odds ratio and confidence interval could not be computed for “Other” role category for one item due to the small sample size and heterogeneous responses

After adjusting for role, experience (months at agency) was associated with a greater desire for consultation regarding the availability of necessary resources for TF-CBT (OR = 1.01, 95% CI [1.00, 1.01], p = .020).

3.6. Two Greatest Perceived Barriers

At least one response was provided by 232 of the 263 survey completers (88.2%). Of participants who provided at least one valid response, 59.9% identified a second barrier for a total of 370 discrete perceived barriers. See Table 4 for a detailed breakdown of responses. Reiterating results from the quantitative data, competing demands for time was overwhelmingly identified as one of the greatest barriers (31.6% of responses). Of pre-specified topics, the next most commonly specified barriers were understanding how to effectively conduct the treatment at 8.1%, and was reimbursement at 7.3%. However, several additional topics were identified that were not included among the pre-specified list. These included “Client/Structural Barriers” (12.2% of responses). These often reflected pragmatic and systemic barriers that existed for patients:

Table 4.

Thematic content of responses to “two greatest barriers” by primarily role for the 370 discrete coded responses

| Overall |

Senior Leader |

Coordinator |

Clinical Supervisor |

Clinician | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 370 | N = 42 |

N=39 N |

N = 42 | N = 236 | N = 11 | |

| N / % | N / % | N / % | N / % | N / % | N / % | |

| Original Categories | ||||||

| Competing demands for time | 117 / 31.6% | 12 / 28.5% | 13 / 33.3% | 15 / 35.7% | 76 / 32.2% | 1 / 9.1% |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 11 / 3.0% | 1 / 2.4% | 3 / 7.7% | 7 / 3.0% | ||

| Communication and collaboration with referral source and systems |

10 / 2.7% | 2 / 4.8% | 6 / 2.5% | 2 / 18.2% | ||

| Knowledge of strategies for systematically addressing problems |

2 / 0.5% | 2 / 0.8% | ||||

| Ability to understand and use agency data | 5 / 1.4% | 1 / 2.4% | 1 / 2.4% | 3 / 1.3% | ||

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards making changes | 3 / 0.8% | 3 / 1.3% | ||||

| Funding/reimbursement rates to support/incentivize treatment | 27 / 7.3% | 12 / 28.5% | 3 / 7.7% | 2 / 4.8% | 10 / 4.2% | |

| Understanding of how-to effectively conduct therapy with fidelity |

30 / 8.1% | 4 / 10.3% | 2 / 4.8% | 19 / 8.1% | 5 / 45.5% | |

| Provision of necessary resources | 17 / 4.6% | 1 / 2.4% | 1 / 2.6% | 15 / 6.4% | ||

| Effectiveness of team meetings | 4 / 1.1% | 1 / 2.4% | 3 / 1.3% | |||

| Availability of quality clinical supervision | 12 / 3.2% | 1 / 2.4% | 3 / 7.7% | 1 / 2.4% | 7 / 3.0% | |

| Agency policies that impact implementation | 6 / 1.6% | 6 / 2.5% | ||||

| State/federal policies about mental health services | ||||||

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards evidence-based practice |

4 / 1.1% | 1 / 2.4% | 2 / 4.8% | 1 / 0.4% | ||

| Requests for treatment from families and referrals | 24 / 6.5% | 2 / 4.8% | 1 / 2.6% | 3 / 7.1% | 18 / 7.6% | |

| Selection of appropriate staff and clinicians | 5 / 1.4% | 4 / 1.7% | 1 / 9.1% | |||

| Commitment and support from leadership | 3 / 0.8% | 2 / 4.8% | 1 / 0.4% | |||

| Understanding of the theory, rationale and evidence-base | 3 / 0.8% | 2 / 4.8% | 1 / 0.4% | |||

| Added Categories | ||||||

| Client or structural barriers | 45 / 12.2% | 2 / 4.8% | 4 / 10.3% | 3 / 7.1% | 35 / 14.8% | 1 / 9.1% |

| Issues with training and turnover | 31 / 8.4% | 5 / 11.9% | 5 / 12.8% | 8 / 19.0% | 13 / 5.5% | |

| Competition with other implementation initiatives | 5 / 1.4% | 1 / 2.4% | 1 / 2.6% | 3 / 1.3% | ||

| Concerns about complex or ongoing trauma | 5 / 1.4% | 1 / 2.4% | 1 / 2.6% | 3 / 1.3% | ||

| Dislike of therapeutic modality | 1 / 0.2% | 1 / 9.1% |

Note. N refers to the number of responses, not the number of participants

“It can be difficult with our clients’ family statuses and situations to include the parents regularly in treatment.” (Clinician)

“Some families have difficulties keeping regularly scheduled sessions due to multiple barriers (transportation, stressors, etc.).” (Coordinator)

“Parking and the cost/reimbursement is a challenge for families. We can only reimburse for 1 hour of parking each visit, which doesn’t work if we want to do back-to-back sessions so families don’t need to come in two different days’” (Senior Leader)

Another frequent concern related to the availability of training given the rate of turnover in many of the clinics (8.4% of responses).

“Staff turnover tends to be an issue for the agency as a whole and makes engagement with clients difficult.” (Clinician)

“The greatest barrier is keeping a stable team. Turnover is really high and we haven’t been able to establish a consistent team. We now lost another staff member and have only one trained staff member and two that just attended a 2-day training.” (Coordinator)

3.7. Two Greatest Consultation Needs

At least one response was provided by 235 of the 263 survey completers (89.4%). Of participants who provided at least one valid response, 55.7% provided a second response for a total of 366 discrete topics. See Table 5 for a detailed breakdown of responses. Respondents indicated an overwhelming desire for consultation focused on how to conduct the treatment with fidelity (33.6% of responses). The next largest desired topics for consultation included addressing secondary trauma among staff (6.0% of responses), time (6.0% of responses), addressing client/structural barriers (5.2% of responses) and training/turnover (4.9 of responses%).

Table 5.

Thematic content of responses to “two most critical consultation topics” by primarily role for the 366 discrete coded responses

| Overall |

Senior Leader |

Coordinator |

Clinical Supervisor |

Clinician | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 366 | N= 45 | N= 35 | N= 42 | N= 228 | N= 16 | |

| N / % | N / % | N / % | N / % | N / % | N / % | |

| Original Categories | ||||||

| Competing demands for time | 22 / 6.0% | 1 / 2.2% | 2 / 5.7% | 3 / 7.1% | 16 / 7.0% | |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 22 / 6.0% | 2 / 4.4% | 2 / 5.7% | 3 / 7.1% | 14 / 6.1% | 1 / 6.3% |

| Communication and collaboration with referral source and systems |

13 / 3.6% | 4 / 8.9% | 2 / 5.7% | 1 / 2.4% | 6 / 2.6% | |

| Knowledge of strategies for systematically addressing problems |

6 / 1.6% | 1 / 2.9% | 4 / 1.8% | 1 / 6.3% | ||

| Ability to understand and use agency data | 9 / 2.5% | 3 / 6.7% | 1 / 2.4% | 5 / 2.2% | ||

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards making changes | ||||||

| Funding/reimbursement rates to support/incentivize treatment | 14 / 3.8% | 5 / 11.1% | 2 / 4.8% | 7 / 3.1% | ||

| Understanding of how-to effectively conduct therapy with fidelity |

123 / 33.6% | 10 / 22.2% | 12 / 34.3% | 16 / 38.1% | 79 / 34.6% | 6 / 37.5% |

| Provision of necessary resources | 10 / 2.7% | 1 / 2.2% | 9 / 3.9% | |||

| Effectiveness of team meetings | 4 / 1.1% | 1 / 2.4% | 3 / 1.3% | |||

| Availability of quality clinical supervision | 12 / 3.3% | 2 / 4.4% | 2 / 5.7% | 2 / 4.8% | 5 / 2.2% | 1 / 6.3% |

| Agency policies that impact implementation | 5 / 1.4% | 2 / 4.8% | 3 / 1.3% | |||

| State/federal policies about mental health services | 2 / 0.5% | 2 / 4.4% | ||||

| Agency culture and staff attitudes towards evidence-based practice |

2 / 0.5% | 1 / 2.4% | 1 / 0.4% | |||

| Requests for treatment from families and referrals | 8 /2.2% | 1 / 2.2% | 1 / 2.9% | 1 / 2.4% | 4 / 1.8% | 1 / 6.3% |

| Selection of appropriate staff and clinicians | ||||||

| Commitment and support from leadership | 3 / 0.8% | 1 / 2.4% | 2 / 0.9% | |||

| Understanding of the theory, rationale and evidence-base | 11 / 3.0% | 1 /2.2% | 1 / 2.9% | 2 / 4.8% | 6 / 2.6% | 1 / 6.3% |

| Added Categories | ||||||

| Client or structural barriers | 19 / 5.2% | 2 / 4.4% | 1 / 2.9% | 14 / 6.1% | 2 / 12.5% | |

| Issues with training and turnover | 18 / 4.9% | 3 / 6.7% | 4 / 11.4% | 3 / 7.1% | 8 / 3.5% | |

| Competition with other implementation initiatives | 2 / 0.5% | 1 / 2.9% | 1 / 0.4% | |||

| Concerns about complex or ongoing trauma | 14 / 3.8% | 3 / 6.7% | 1 / 2.9% | 1 / 2.4% | 9 / 3.9% | |

| Challenges with initial engagement of clients/families | 10 / 2.7% | 1 / 2.2% | 8 / 3.5% | 1 / 6.3% | ||

| Tailoring treatment based on individual differences | 25 / 6.8% | 3 / 6.7% | 3 / 8.6% | 1 / 2.4% | 17 / 7.5% | 1 / 6.3% |

| Addressing client/therapist resistance or avoidance | 12 / 3.3% | 1 / 2.2% | 2 / 5.7% | 1 / 2.4% | 7 / 3.1% | 1 / 6.3% |

Note. N refers to the number of responses, not the number of participants.

Several additional key themes emerged from data on treatment implementation. These included strategies for tailoring the treatment to meet the needs of individual clients (6.8% of responses), strategies for addressing complex or ongoing trauma (3.8% of responses), challenges with initial client engagement (2.7% of responses), and addressing client/therapist resistance or avoidance (3.3% of responses).

“How to engage clients or parents who are resistant to discussing the trauma.” (Clinical Supervisor) “More discussion around helping cognitive-limited children understand the concepts of TF-CBT” (Clinician)

“Having actual clients to work with as we are a residential facility and rarely do we have a traumatized child who is able to actually complete this work without first AWOLing” (Clinician)

“How to adjust the model to the needs of clients who have experienced complex trauma and continue to live in an environment that continuously promotes new traumatic experiences” (Clinician)

4. Discussion

Overall, these findings reveal a number of important issues regarding barriers to implementation of trauma-focused EBTs and best practices for implementation consultation. First it should be noted that of the pre-specified barriers, most were not perceived as significant problems. In fact, 17 out of 18 barriers were endorsed at the lowest levels (“Not at all a barrier” or “A little bit of a barrier”) by > 50% of respondents. It is possible that the systematic implementation approach provided via the BSC (Ebert, Amaya-Jackson, Markiewicz, Kisiel, & Fairbank, 2012; Kilo, 1998) and the ongoing implementation support provided by the Support Center (CITATION BLINDED FOR REVIEW) contributed to these perceptions, mitigating the impact of many common barriers when such supports are not available to community-based providers. If so, these results may not generalize to less structured implementation efforts. A number of other plausible explanations also exist. Although the included agencies were fairly typical of outpatient community mental health settings, their willing participation in the broader implementation initiative raises the possibility that these agencies are better poised than average agencies to implement such changes. Other agency-specific factors may also have contributed to these findings. Alternatively, given many respondents had ongoing contact with consultants it is possible that social desirability impacted responses.

Although these findings are encouraging with regards to the potential for implementation of EBTs in community settings, it is also possible that the lone exception -- competing demands for time (which was endorsed at high levels by > 70% of respondents) -- poses such an overwhelming barrier for most community agencies as to significantly hinder implementation on its own. The present study suggested that competing demands for time was much less of a concern among individuals with “Other” roles - typically trainees or administrative staff. The range and diversity of roles within this category makes interpretation somewhat challenging. Nonetheless, agencies implementing EBTs may benefit from delegating many of the non-clinical responsibilities (e.g. managing communications with coordinating sites and referral sources) that accompany many implementation efforts to staff in other roles. Trainees in particular may benefit from the opportunity to be involved in implementation projects, even if their greater rate of turnover renders receipt of formal specialized clinical training impractical.

Secondary traumatic stress also stood out as a perceived barrier to TF-CBT implementation, though to a lesser degree than time demands. Though endorsed with enough frequency to be of concern, it is worth noting that senior leaders expressed significantly greater concern about this issue than did clinicians. This difference in perceptions about secondary traumatic stress on clinicians will be important to explore in future research. For example, it may be that senior leaders overestimate the severity of this problem or that clinicians under-report secondary traumatic stress, perhaps due to stigma or other concerns about how supervisors will perceive them.

Qualitative responses enabled the identification of two significant barriers not included in the original list: client/structural barriers and challenges related to staff turnover and training. The former has been identified as a significant barrier to mental health care in general and is not necessarily specific to implementation of an EBT (Drapalski, Milford, Goldberg, Brown, & Dixon, 2008; Owens et al., 2002). Nonetheless, components emphasized in TF-CBT and many other EBTs (e.g. parental involvement, regular attendance) may make these barriers more salient and problematic. However, the particularly structured nature of TF-CBT may contribute to reluctance among clinicians if they believe client factors will preclude adherence to this structure. A case-by-case problem-solving approach may address select barriers, but many structural barriers are unlikely to be easily resolved in this manner. Coordination with state and local governments, as well as increased collaboration between agencies and referral sources may provide more long-term solutions. Many of these issues can also be addressed up front, through increased research aimed at identifying active ingredients and effectiveness and the creation/adoption of flexible treatment manuals. Staff turnover has also been identified as a significant barrier in previous research (Woltmann et al., 2008). Greater time pressure and secondary traumatic stress may contribute to turnover (Boyas & Wind, 2010), efforts to address these issues could theoretically carry the downstream benefit of reducing turnover. However, given turnover is likely to continue to pose somewhat of a challenge in these settings, support to facilitate training of new staff is of heightened importance. Increasing communication between community agencies and academic sites, as well as increased reliance on coordinating centers and other centralized agencies responsible for ensuring access to training may help address concerns. In addition, train-the-trainer approaches have been widely used to foster sustainable evidence-based medical and mental health practices across a number of settings and may also play a role in addressing this issue (Martino et al., 2011).

Quantitative results indicated a desire for consultation focused on the same two barriers (competing demands for time, secondary traumatic stress) identified as the greatest perceived barriers. However, qualitative results diverged from this markedly with an emphasis on actual clinical training. It is possible some respondents perceived these two issues as inherent to the setting/treatment and therefore believe consultation is unlikely to lead to effective solutions. Regardless, findings clearly indicated an overwhelming desire for consultation focused on training in how to deliver the EBT. This may indirectly relate to some barriers noted above (e.g. high rate of staff turnover). Staff also may develop a more nuanced view of the treatment, as they experience difficulties implementing the treatment with individual children. Topics such as ongoing/complex trauma, treatment resistance, and adaptation of the treatment to meet individual patient needs (e.g. cognitive limitations, comorbid diagnoses) suggest a key role of consultants can be to foster transitions from competence to expertise in treatments over the course of implementation efforts.

There is significant need for treatments that address traumatic stress in children, particularly at community agencies treating subgroups of children with higher rates of exposure to potentially traumatic events (Greeson et al., 2011). Unfortunately, those same agencies commonly experience barriers that make implementation of these practices difficult and have less institutional support/expertise that can assist with implementation. Results from the present study identified several key barriers to successful implementation of such a practice present at a variety of community agencies involved in an organized implementation effort and desired foci for ongoing consultation efforts that can inform similar implementation efforts. Many of these topics overlap substantially with previously identified barriers to implementation of any EBT (e.g. time, capacity; Palinkas et al., 2017). Interestingly, other topics that have received significant attention as potential barriers (e.g. attitudes towards EBTs, availability of quality clinical supervision) were not perceived as major barriers (Aarons, 2004; Bearman et al., 2013).

Several limitations inherent to the project should be noted. First, it is possible that inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative components may have caused participants to artificially confine their qualitative responses to predetermined categories. Another particularly key limitation of the present study is that many respondents had been involved with the broader implementation effort for several years and the challenges faced may differ from agencies just beginning implementation or that are attempting to implement an EBT independently rather than as part of a coordinated effort. The application of a BSC model for this purpose is also likely to have impacted perceptions of barriers and consultation needs, given the development of inter-agency communication and support is a key feature of this model. Thus, it is possible topics that would normally be noted as barriers or desired foci of consultation are readily addressed via the BSC. However, the absence of a control condition precludes us from making definitive statements about the role of the BSC. Agencies also varied significantly in the length of time they had been participating in the initiative. This provides some assurance that present results generalize to agencies at all stages of implementation, but findings may nonetheless differ when examining agencies at specific stages of implementation and this remains an important direction for future research. In addition, responses were obtained from only 60.1% of participants so it is possible that some perspectives may have differed among individuals who did not participate. Given turnover was cited as a major barrier at several agencies, it is plausible that turnover impacted response rates, which could potentially bias results.

Nonetheless, the barriers and desired foci for consultation identified herein likely represent topics of significant concern for many similar agencies, regardless of their participation in such a program. The present study was not powered to do so, but future research should extend this work to examine the role of agency-level factors (e.g. size, financial resources). In addition, research aimed at developing and evaluating strategies for addressing specific barriers highlighted here is likely to be beneficial. Doing so is likely to increase implementation of evidence-based trauma care practices in community agencies, increase access, and ultimately improve child welfare and public health.

Highlights.

Insufficient time and secondary trauma are significant implementation barriers

Additional challenges include client barriers, turnover and insufficient training

Perceived barriers and consultation needs differ as a function of professional role

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the [BLINDED] Department of Children and Families. Additional support was provided by grant [BLINDED] from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to [BLINDED]. The sponsors had no further input on the content of this manuscript beyond provision of funding. The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the role of staff members at the [BLINDED].

Online Appendix

Survey Questions

What agency are you affiliated with for purposes of the TF-CBT initiative? If more than one, choose the one you are at the most.

- What is/are your roles with regards to the TF-CBT project? (select all that apply)

- Clinician

- Clinical Supervisor

- Coordinator

- Data Entry Specialist

- Senior Leader

- Other (specify:———

- How long have you been... Years Months

- Working at this agency?

- Involved with TF-CBT at this agency?

How much experience did you have with TF-CBT prior to your involvement with this project?

No experience A little experience Some experience Quite a bit of experience Substatial experience

-

5.

The section below identifies a number of broad categories that might be addressed through consultation. We would like you to indicate: A) Whether or not you perceive this issue to be a barrier to successful implementation - by a barrier, we mean that something that prevents your agency from being able to fully implement the TF-CBT model; and B) To what extent you believe the implementation consultants should focus on addressing this issue during consultation calls/meetings.

Scales:

1 = Not at all a barrier 1 = Not at all a focus

2 = A little bit of a barrier 2 = A little bit of a focus

3 = Somewhat of a barrier 3 = Somewhat of a focus

4 = Very much a barrier 4 = Very much a focus

5 = An extreme barrier 5 = An extreme focus

| How much of a barrier to successful implementation is this for your agency? | How much of a focus should this be during consultation calls and visits? | |

| A. Understanding of the theory, rationale and evidence-base for TF-CBT |

——— | ——— |

| B. Understanding of how to effectively conduct TF-CBT with fidelity for appropriate clients |

——— | ——— |

| C. Availability of quality clinical supervision in TF-CBT at my agency |

——— | ——— |

| D. Effectiveness of TF-CBT team meetings for addressing implementation concerns |

——— | ——— |

| E. Ability to understand and use agency data (e.g. metrics, clients served) to identify our strengths and weaknesses |

——— | ——— |

| F. Commitment and support from leadership at our agency | ——— | ——— |

| G. Selection of appropriate staff and clinicians for the TF-CBT team |

——— | ——— |

| H. Provision of necessary resources (e.g. computers, funding, etc.) |

——— | ——— |

| I. Competing demands for time/excessive workload | ——— | ——— |

| J. Secondary traumatic stress/concerns about self-care among staff members |

——— | ——— |

| K. Agency culture and staff attitudes towards making changes to the way we do things in general |

——— | ——— |

| L. Agency culture and staff attitudes towards evidence-based practice |

——— | ——— |

| M. Agency policies that impact TF-CBT implementation | ——— | ——— |

| N. Communication and collaboration with referral sources and other systems/agencies |

——— | ——— |

| O. Knowledge of strategies for systematically addressing problems and engaging in quality improvement |

——— | ——— |

| P. State/federal policies about mental health services/evidence- based practice |

——— | ——— |

| Q. Funding/reimbursement rates to support/incentivize TF-CBT | ——— | ——— |

| R. Requests for TF-CBT from families and those who refer children for treatment |

——— | ——— |

-

6.

What are the two greatest barriers your agency faces with regards to implementing TF-CBT? Feel free to choose from the categories on the previous page, or describe your own. <free response>

-

7.

What are the two topics you think are most critical for the consultants to address during consultation calls/meetings with your agency? Again, feel free to choose from the topics mentioned on the previous page or describe your own. <free response>

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jason A. Oliver, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Mailing Address: 2608 Erwin Rd., Suite 300, Durham NC 27705, Phone: 919-668-0093, Jason.A.Oliver@dm.duke.edu.

Jason M. Lang, Vice President for Mental Health Initiatives, Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut, Inc.

References

- Aarons GA (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Ment Health Serv Res, 6(2), 61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, & Palinkas LA (2007). Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: service provider perspectives. Adm Policy Ment Health, 34(4), 411–419. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, Fettes DL, & Palinkas LA (2009). Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: A multiple stakeholder analysis. American journal of public health, 99(11), 2087–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Wade WA, & Hatgis C (1999). Barriers to dissemination of evidence-based practices:Addressing practitioners’ concerns about manual-based psychotherapies. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 6(4), 430–441. [Google Scholar]

- Allen B, & Johnson JC (2012). Utilization and implementation of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of maltreated children. Child Maltreat, 17(1), 80–85. doi: 10.1177/1077559511418220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer TE, Liberman RP, & Kuehnel TG (1986). Dissemination and adoption of innovative psychosocial interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol, 54(1), 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Barto B, Griffin JL, Fraser JG, Hodgdon H, & Bodian R (2016). Trauma-Informed Care in the Massachusetts Child Trauma Project. Child Maltreat, 21(2), 101–112. doi: 10.1177/1077559515615700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Hoagwood K, Ward A, Ugueto AM, … Research Network on Youth Mental, H. (2013). More practice, less preach? the role of supervision processes and therapist characteristics in EBP implementation. Adm Policy Ment Health, 40(6), 518–529. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0485-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Stewart RE, Adams DR, Fernandez T, Lustbader S, Powell BJ, ... & Rubin R (2016). A multi-level examination of stakeholder perspectives of implementation of evidence-based practices in a large urban publicly-funded mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 893–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyas J, & Wind LH (2010). Employment-based social capital, job stress, and employee burnout: A public child welfare employee structural model. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(3), 380–388. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt JT, Schroter DC, Magura S, Means SN, & Coryn CL (2015). An overview of evidence- based program registers (EBPRs) for behavioral health. Evaluation and program planning, 48, 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, & Steer RA (2004). A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 43(4), 393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Berliner L, & Deblinger E (2000). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents an empirical update. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(11), 1202–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. ImplementSci, 4, 50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Arellano MA, Lyman DR, Jobe-Shields L, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, … Delphin- Rittmon ME (2014). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv, 65(5), 591–602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Milford J, Goldberg RW, Brown CH, & Dixon LB (2008). Perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv, 59(8), 921–924. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert L, Amaya-Jackson L, Markiewicz JM, Kisiel C, & Fairbank JA (2012). Use of the breakthrough series collaborative to support broad and sustained use of evidence-based trauma treatment for children in community practice settings. Adm Policy Ment Health, 39(3), 187–199. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0347-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, & Friedman RM (2005). Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. [Google Scholar]

- Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, Pakiz B, Frost AK, & Cohen E (1995). Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. JAm Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 34(10), 1369–1380. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, & Janson S (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet, 373(9657), 68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Atkinson S, & Williams NJ (2012). Randomized trial of the Availability, Responsiveness, and Continuity (ARC) organizational intervention with community- based mental health programs and clinicians serving youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 51(8), 780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, & Williams NJ (2013). Randomized trial of the Availability, Responsiveness and Continuity (ARC) organizational intervention for improving youth outcomes in community mental health programs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 52(5), 493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AE, & Aarons GA (2011). A comparison of policy and direct practice stakeholder perceptions of factors affecting evidence-based practice implementation using concept mapping. Implementation Science, 6(1), 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JK, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, Layne CM, Ake GS 3rd, Ko SJ, … Fairbank JA (2011). Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare, 90(6), 91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, & Gumport NB (2015). Evidence-based psychological treatments for mental disorders: Modifiable barriers to access and possible solutions. Behav Res Ther, 68, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Olin SS, Horwitz S, McKay M, Cleek A, Gleacher A, … Hogan M (2014). Scaling up evidence-based practices for children and families in New York State: toward evidence-based policies on implementation for state mental health systems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 43(2), 145–157. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.869749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover SA, Sapere H, Lang JM, Nadeem E, Dean KL, & Vona P (2018). Statewide implementation of an evidence-based trauma intervention in schools. Sch Psychol Q, 33(1), 44–53. doi: 10.1037/spq0000248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: new opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. Am Psychol, 63(3), 146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilo CM (1998). A framework for collaborative improvement: lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series. QualManagHealth Care, 6(4), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang JM, Franks RP, Epstein C, Stover C, & Oliver JA (2015). Statewide dissemination of an evidence-based practice using Breakthrough Series Collaboratives. Children and Youth Services Review, 55, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, & Jaycox LH (2010). Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: Barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School mental health, 2(3), 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Rounsaville BJ, & Carroll KM (2011). Teaching community program clinicians motivational interviewing using expert and train-the-trainer strategies. Addiction, 106(2), 428–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03135.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, & Foa EB (2013). Dissemination and implementation of prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord, 27(8), 788–792. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D (2012). Seizing opportunities under the Affordable Care Act for transforming the mental and behavioral health system. Health Aff (Millwood), 31(2), 376–382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, & Herbison GP (1996). The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: a community study. Child Abuse Negl, 20(1), 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, Hoagwood KE, & Horwitz SM (2014). A literature review of learning collaboratives in mental health care: used but untested. Psychiatric Services, 65(9), 1088–1099. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, & Ialongo NS (2002). Barriers to children’s mental health services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 41(6), 731–738. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol, 61(4), 271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Um MY, Jeong CH, Chor KHB, Olin S, Horwitz SM, & Hoagwood KE (2017). Adoption of innovative and evidence-based practices for children and adolescents in state-supported mental health clinics: a qualitative study. Health research policy and systems, 15(1), 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy MentHealth, 36(1), 24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau DM, & Gunia BC (2016). Evidence-Based Practice: The Psychology of EBP Implementation.Annu Rev Psychol, 67, 667–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher DS (2000). Executive summary: a report of the Surgeon General on mental health. Public Health Rep, 115(1), 89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, & Hoagwood K (2001). Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatr Serv, 52(9), 1190–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TA (2011). Multilevel analysis: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stirman SW, Crits-Christoph P, & DeRubeis RJ (2004). Achieving successful dissemination of empirically supported psychotherapies: A synthesis of dissemination theory. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 11(4), 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, ... & Saul, J. (2008). Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. American journal of community psychology, 41(3–4), 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, Brunette M, Torrey WC, Coots L, … Drake RE (2008). The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv, 59(7), 732–737. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.7.732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]