Abstract

Objectives

Few studies have investigated the psychological and health-related outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) over time. This longitudinal study aims to evaluate psychological distress in terms of anxiety and depression, self-assessed health and predictors of these outcomes in survivors of OHCA, 3 and 12 months after resuscitation.

Methods

Recruitment took place from 2008 to 2011 and survivors of OHCA were identified through the national Swedish Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Registry. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, survival ≥12 months and a Cerebral Performance Category score ≤2. Questionnaires containing the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) were administered at 3 and 12 months after the OHCA. Participants were also asked to report treatment-requiring comorbidities.

Results

Of 298 survivors, 85 (29%) were eligible for this study and 74 (25%) responded. Clinically relevant anxiety was reported by 22 survivors at 3 months and by 17 at 12 months, while clinical depression was reported by 10 at 3 months and 4 at 12 months. The mean EQ-5D-3L index value increased from 0.82 (±0.26) to 0.88 (±0.15) over time. There were significantly less symptoms of psychological distress (p=0.01) and better self-assessed health (p=0.003) at 12 months. Treatment-requiring comorbidity predicted anxiety (OR 4.07, p=0.04), while being female and young age predicted poor health (OR 6.33, p=0.04; OR 0.91, p=0.002) at 3 months. At 12 months, being female was linked to anxiety (OR 9.23, p=0.01) and depression (OR 14.78, p=0.002), while young age predicted poor health (OR 0.93, p=0.003).

Conclusion

The level of psychological distress and self-assessed health improves among survivors of OHCA between 3 and 12 months after resuscitation. Higher levels of psychological distress can be expected among female survivors and those with comorbidity, while survivors of young age and who are female are at greater risk of poor health.

Keywords: follow-up, outcome, anxiety, quality of life, cardiac arrest

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data were collected from virtually every out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivor within the course of 4 years in a large region of Sweden.

A nurse responsible for data collection was placed at each hospital in the region to match survivors with data from the Swedish Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Registry.

Only survivors with a Cerebral Performance Category score of ≤2 were included.

The use of generic measures of health has a limited ability to capture the complexity of the health state in survivors of cardiac arrest.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a deadly condition that affects approximately 5000 inhabitants in Sweden each year.1 The survival rate of OHCA is low, although great efforts have been made to raise the number of survivors in recent years; consequently, the 30-day survival rate in Sweden has increased from 4.5% in 1992 to 11.4% in 2017.2 When the heart stops, hypoxic brain injury occurs within minutes and is the most critical factor in determining the chance of survival and level of functioning, if resuscitation is successful.3 Following cerebral hypoxia, cardiac arrest survivors are known to be at risk of cognitive and emotional deficits.4–7 Although most survivors with a good neurological outcome return to high function and quality of life,8 9 long-term psychological problems have been reported by up to one-third in Swedish samples.10 11 Furthermore, the ability to pinpoint survivors who need psychiatric rehabilitation will become more important as survival rates continue to increase.

There is already an extensive body of knowledge regarding the outcome after cardiac arrest in different patient populations and time points. Time to awakening, gender, age, role of bystander, use of hypothermia and percutaneous coronary intervention have previously been related to the outcome after cardiac arrest.6 12 13 However, few studies have investigated the psychological and health-related outcome in the same sample over time,9 10 14 and little is known about factors associated with postcardiac arrest improvement in these aspects. The interpretation of the available literature is complicated by high heterogenicity in study outcomes, and knowledge regarding psychological distress and self-assessed health after OHCA in relation to the average population is lacking.7 15

We have previously reported that reduced well-being is experienced by half of OHCA survivors at 3 months, and that female survivors report significantly more anxiety and worse health compared with males.16 In this study, we will investigate how the psychological and health-related outcomes change in survivors of OHCA with good neurological functioning between 3 and 12 months after resuscitation. Further, we will also evaluate gender differences as well as predictors of psychological distress and self-assessed poor health at these time points.

Methods

Design and setting

This was a longitudinal study with self-administered postal questionnaires sent to survivors 3 and 12 months after the OHCA. The setting was a region in Sweden with 1.6 million inhabitants and nine hospitals that treat cardiac arrest. The frequency of OHCA was 850 cases annually and the survival rate approximately 10%.

Study population

The study population was identified through the national Swedish Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Registry (SCRR). Every person who suffered from an OHCA and for whom resuscitation was initiated should be included in the SCRR. To ensure complete coverage, there was a specially trained nurse at each hospital who could identify missing cases and match patients treated for OHCA with data from the SCRR.

Recruitment took place from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2011 and every adult survivor of OHCA in the region was assessed for inclusion. The study inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, survival ≥12 months and a Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) score ≤2 at discharge, denoting good neurological functioning.17 Exclusion criteria were cardiac arrest due to trauma, attempted suicide, intoxication or abuse. Survivors with other severe illness and survivors treated but not residing in the region were also excluded.

Procedure and questionnaire

Eligible survivors received a postal questionnaire in Swedish 3 months after the OHCA. Survivors who responded to the questionnaires and gave a written consent were included. Participants at 3 months then received a second questionnaire at 12 months. A reminder was sent if no response was received after 3 weeks. The questionnaire consisted of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level (EQ-5D-3L). Study participants were also asked to report treatment-requiring comorbidity.

The HADS is a 14-item screening instrument developed to detect psychological distress in terms of clinically significant anxiety and/or depression.18 It is divided into two subscales, seven items regarding anxiety (HADS-anxiety) and seven items regarding symptoms of depression (HADS-depression). Each item has four levels, scored 0–3, with a maximum score of 21 in each subscale. Scoring >7 in one subscale indicates mild to moderate problems and a score >10 indicates severe problems. Although the HADS has never been thoroughly evaluated in a cardiac arrest population, it is considered a reliable measurement for depression and anxiety in patients with somatic illness19 and is frequently used in cardiovascular research.7

EQ-5D-3L is designed to measure subjective health and includes the EQ-5D-3L descriptive system and a Visual Analogue Scale (EQ VAS).20 The descriptive system comprises five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression); each dimension has three levels (no problems, moderate problems and severe problems) denoting a score of 1–3. The total score in the EQ-5D-3L descriptive system can be converted to an index value which ranges between −0.594 and 1.00, calculated with the UK EQ-5D index tariff.21 An index value of 1.00 indicates full health, while negative values represents health states worse than death.20 EQ VAS is visualised as a continuum of value scale where the patient assesses his or her current health on a scale from 0 to 100, with endpoints labelled ‘best imaginable health state’ and ‘worst imaginable health state’. EQ-5D-3L is commonly used in cardiovascular research.22 However, the use of EQ-5D-3L in OHCA populations has been questioned as the instrument has shown a limited ability to differentiate between survivors of good health.23

Statistics and data analysis

Statistical analyses were executed with IBM SPSS Statistics V.24.0. All p values were two-sided and interpreted at a 0.05 significance level. Non-parametric tests were used for all comparisons as all dependent variables were non-normally distributed. The χ2 test was applied for nominal values and the Mann-Whitney U-test for ordinal values. Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to explore the change between 3 and 12 months. Predictors of psychological distress (HADS) and self-assessed poor health (EQ-5D-3L index values) were investigated using multivariate binary logistic regression models. The outcome was dichotomised as good or bad with regard to the mean scores in two Swedish reference populations, matched to gender and age-group. A bad outcome was considered a score 2 SD below the mean of the reference population. Reference values regarding the HADS were drawn from a random sample gathered 1997 in Jämtland County, Sweden (n=624);24 similarly, reference values regarding the EQ-5D-3L index values were drawn from a random sample gathered 2001 in Stockholm County, Sweden (n=3069).25 The predictors were included based on clinical reasoning and are presented in table 1. With regard to the sample size, only six variables were evaluated and correlations between them were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation; only variables with a Spearman’s r ±≤0.7 were accepted. Univariate analysis was conducted separately between each individual predictor. The significant level of the univariate analysis was 0.25 and predictors with a p value >0.25 were excluded from further analysis. Hosmer and Lemeshow tests and receiver operating characteristics curves were performed to ensure the reliability of the logistic regression models.

Table 1.

Background characteristics and self-reported comorbidity of participants

| n (%) unless otherwise stated | Participants, n=74 | Missing data* |

| Age, median (min–max)† | 63 (25–89) | |

| Female† | 13 (18) | |

| Time to EMS in minutes, median (min– max) | 7 (1–61) | 11 |

| Cardiac arrest circumstances | ||

| Cardiac aetiology† | 62 (86) | 2 |

| Cardiac arrest at home | 22 (30) | |

| CPR before arrival of EMS | 41 (55) | |

| Initial rhythm: VF or VT | 61 (86) | 3 |

| Witnessed cardiac arrest | 69 (95) | 1 |

| In-hospital interventions | ||

| CABG | 5 (7) | 2 |

| ICD† | 19 (27) | 4 |

| Induced hypothermia (33°C)† | 35 (49) | 2 |

| PCI | 39 (54) | 2 |

| Comorbidity‡† | 60 (81) | |

| Anaemia or other blood disease | 0 | |

| Back pain | 3 (4) | |

| Cancer | 1 (1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (3) | |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 5 (7) | |

| Heart disease | 54 (73) | |

| Hypertension | 27 (36) | |

| Liver disease | 1 (1) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 2 (3) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 3 (4) | |

| Renal disease | 0 | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (1) | |

*Number of participants where information is missing.

†Variables included as predictors in the univariate regression analyses.

‡Number of participants with self-reported treatment-requiring comorbidity.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CPR, cardiopulmonary resurrection; EMS, emergency medical service; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT ventricular tachycardia.

Patient and public involvement

None of the included patients were involved in the design or conduction of this study and no patient opinion regarding the subject has been obtained. The results will be reported to the Health and Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden.

Results

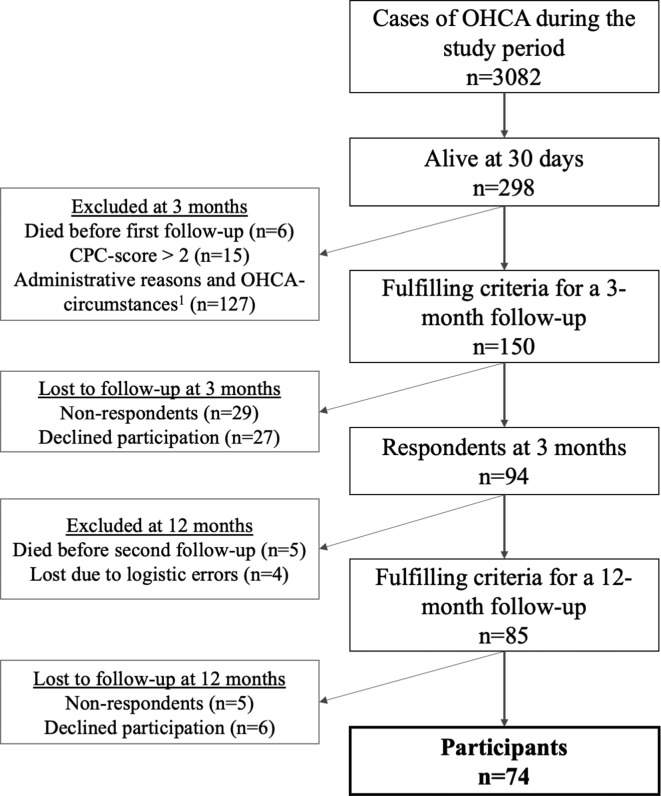

There were 3082 cases of OHCA in the region during the study period, of which 298 were alive at 30 days. One hundred and fifty survivors fulfilled the inclusion criteria for a 3-month follow-up and 94 responded. Of the respondents at 3 months, 85 were included at 12 months and 74 responded again (87% response rate); in the group that did not receive a second questionnaire, five had died and four were lost due to logistical errors (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants. CPC, Cerebral Performance Category; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. 1) Administrative reasons include survivors documented with an incorrect social security number, not able to be identified within 3 months or not residing in the region. OHCA-circumstances include trauma, attempted suicide, drowning and intoxication as cause of the cardiac arrest or severe illness afterwards.

The representativeness of the study population has been investigated in a prior study,26 and there were no significant differences regarding age, gender, cardiac arrest circumstances or in-hospital interventions between respondents and non-respondents. However, there were differences between participants and the survivors that only responded once. Double respondents were significantly younger (Z=2.316, p=0.021), had a lower frequency of cardiac arrest at home (χ2=6.249, p=0.014) and a higher frequency of ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia as initial rhythm (χ2=5.067, p=0.032). Background characteristics and self-reported comorbidity of the participants are presented in table 1.

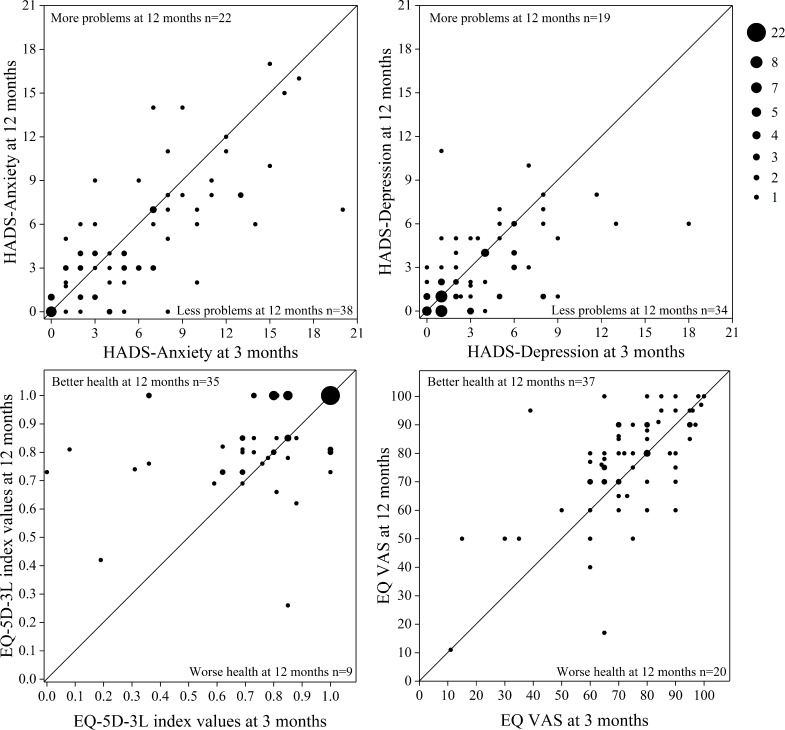

Mild to moderate anxiety (>7 in HADS-A) was reported by 22 (30%) survivors at the 3 months follow-up and by 17 (23%) at 12 months. Mild to moderate depression (>7 in HADS-D) was reported by 10 (14%) survivors at 3 months and by four (5%) at 12 months. A score indicating severe anxiety (>10 in HADS-A) was reported by 12 survivors at 3 months and by eight at 12 months, while severe depression (>10 in HADS-D) was reported by three at 3 months and one at 12 months. Overall, survivors of OHCA reported a significantly improved psychological and health-related outcome over time (table 2). About half of the survivors reported less psychological distress in the HADS at 12 months (51% decrease in anxiety and 46% in symptoms of depression); although one-third reported an increase in psychological distress (30% increase in anxiety and 28% in symptoms of depression). Two-thirds of female survivors reported more psychological distress at the 12-month follow-up, corresponding to one-fifth among male survivors. Comparably, half of the survivors reported better self-assessed health at 12 months in EQ-5D-3L, whereas 41% reported the same health state at 3 and 12 months. Among the survivors who remained unchanged, 73% reported an EQ-5D-3L index value of 1.00, denoting full health at both time points. However, only one survivor entered full health at both times in EQ VAS (figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of mean scores at 3 and 12 months in the HADS and EQ-5D-3L (n=74)

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Z-value | P value | |

| 3 months | 12 months | |||

| HADS | ||||

| HADS-anxiety | 5.6 (±4.8) | 4.7 (±4.3) | 2.337 | 0.02* |

| HADS-depression | 3.4 (±3.5) | 2.6 (±2.6) | 2.199 | 0.03* |

| Total score | 9.0 (±7.8) | 7.3 (±6.5) | 2.579 | 0.01* |

| EQ-5D-3L | ||||

| EQ VAS (n=67) | 73 (±18) | 77 (±19) | 2.292 | 0.02* |

| Index value | 0.82 (±0.26) | 0.88 (±0.15) | 2.966 | 0.003* |

*P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot with individual reported outcomes in the HADS and EQ-5D-3L at 3 months (x-axis) and 12 months (y-axis). Dots above the diagonal lines indicate a higher score at the 12-month follow-up. Scores from seven participants are missing in EQ VAS. EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Binary logistic regression analyses were preformed to find predictors of psychological distress and self-assessed poor health (table 3). The presence of treatment-requiring comorbidity was found to predict more anxiety at 3 months after resuscitation (OR 4.07, p=0.04), but there was no significant OR regarding comorbidity at 12 months; instead, being female was found to predict more anxiety (OR 9.23, p =0.01) and more symptoms of depression (OR 14.78, p=0.002) at this time. Being female was also found to predict self-assessed poor health at 3 months (OR 6.33, p=0.04), while young age was found to predict poor health at 3 and 12 months, respectively (OR 0.91, p=0.002; OR 0.93, p=0.003).

Table 3.

Predictors of psychological distress and self-assessed poor health (n=70)

| 3 months | 12 months | |||||||

| Predictors | OR (95% CI) | SE | P | R2 | OR (95% CI) | SE | P | R2 |

| HADS-anxiety | ||||||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | 0.02 | 0.63 | 0.195 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.276 |

| Comorbidity | 4.07 (1.07 to 17.00) | 0.73 | 0.04* | 3.79 (0.70 to 20.42) | 0.86 | 0.12 | ||

| Being female | 4.94 (0.91 to 26.83) | 0.86 | 0.06 | 9.23 (1.68 to 50.61) | 0.78 | 0.01* | ||

| Hypothermia | 1.25 (0.43 to 3.62) | 0.54 | 0.68 | 1.20 (0.38 to 3.76) | 0.58 | 0.75 | ||

| HADS-depression | ||||||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.04) | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.136 | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.300 |

| Comorbidity | 1.45 (0.33 to 6.44) | 0.76 | 0.62 | 1.20 (0.25 to 5.85) | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||

| Being female | 3.71 (0.90 to 15.37) | 0.78 | 0.07 | 14.78 (2.60 to 83.87) | 0.87 | 0.002* | ||

| Hypothermia | 1.16 (0.37 to 3.61) | 0.58 | 0.81 | 2.75 (0.82 to 9.28) | 0.62 | 0.10 | ||

| ICD | 1.52 (0.40 to 5.69) | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.55 (0.11 to 2.77) | 0.82 | 0.47 | ||

| EQ-5D-3L index value | ||||||||

| Age | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97) | 0.03 | 0.002* | 0.362 | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.98) | 0.02 | 0.003* | 0.288 |

| Comorbidity | 1.19 (0.28 to 5.01) | 0.73 | 0.81 | 2.53 (0.51 to 12.69) | 0.82 | 0.26 | ||

| Being female | 6.33 (1.03 to 38.81) | 0.93 | 0.04* | 2.09 (0.46 to 9.40) | 0.77 | 0.34 | ||

*P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Discussion

One objective of this study was to investigate how the psychological and health-related outcomes change between 3 and 12 months in survivors of OHCA with good neurological functioning. We found an encouraging progression as survivors at large showed less psychological distress and better self-assessed health over time. In comparison, participants in this study even surpassed the average level of depression and self-assessed health in the Swedish population at their 12-month follow-up.24 25 However, we also found that even though about half of OHCA survivors report a decrease in psychological distress between 3 and 12 months, almost one-third report increased psychological distress; hence, our results indicate that the psychological outcome after OHCA may differ considerably on an individual level.

As stated earlier, few prior longitudinal studies have investigated the psychological and health-related outcomes after cardiac arrest. In accordance with our results, two small sample studies have previously reported a decrease of anxiety and depressive symptoms in cardiac arrest survivors over time.13 27 In contrast, a rather large prospective study found no change in anxiety or depressive symptoms between 1 and 12 months.14 It is possible that the heterogeneity in psychological outcomes observed in this study could explain a part of the discrepancies in the available literature. As regards self-assessed health, the improvements seen in this study confirm the results of two previous longitudinal studies.9 10 However, these previous studies found that the greatest health-related improvements occurred in the early stages of recovery, within 3 months after cardiac arrest.9 10 Moreover, although the ‘minimal clinically important difference’ in the HADS and EQ-5D-3L among survivors of cardiac arrest is unknown, estimates from other patient populations indicate that the improvements seen in this study might not be clinically noticeable.28 29

A second objective was to evaluate predictors of psychological distress self-assessed poor health after OHCA. Since it is already known that cardiac arrest survivors generally report few psychological problems and good health, it is difficult to define a threshold for a bad outcome among those who perform well neurologically. In this study, the outcome was dichotomised as good or bad in comparison to mean scores from the average Swedish population. Prior studies have concluded that many survivors reach an psychological state and health comparable to the average population, although no study has previously investigated predictors of this outcome.9 10 30 In addition, there is also a lack of knowledge regarding factors associated with postcardiac arrest improvement over time.13 31 We found that comorbidity is associated with higher levels of anxiety compared with the average population at 3 months after OHCA. However, we did not find a significant association between comorbidity and anxiety or depression at the 12-month follow-up. In contrast, being female was strongly associated with psychological distress at 1 year after resuscitation, but this was not significant at 3 months. We also found a significant association between being female and self-assessed poor health at 3 months, while young age was associated with self-assessed poor health at both 3 and 12 months.

Studies investigating prognostic factors regarding the psychological or health-related outcomes after cardiac arrest are scarce. However, receiving an ICD has been linked to higher levels of psychological distress,32 but this effect has not been shown in a cardiac arrest population.14 We did not find any significant association regarding ICD in our regression models either. Young age and being female have previously been associated with anxiety among cardiac arrest survivors,30 but there were no significant association between psychological distress and age in our study population. Nevertheless, we did find a considerably higher likelihood of depression among female survivors of OHCA at 12 months, which has not previously been reported. Also novel is the likelihood of a better self-assessed health among survivors of higher age.

The European Resuscitation Council has provided guidelines for postcardiac arrest rehabilitation since 2015 and has pointed out the need of a structured follow-up care, including physical, neurological and emotional screening.33 Still, far from all cardiac arrest survivors in Sweden are offered rehabilitation or neuropsychological evaluation, despite recommendations from the Swedish Resuscitation Council.34 35 Instead, survivors in Sweden are often followed based on the aetiology of the cardiac arrest with little to no focus on emotional sequelae.35 36 Our results indicate that even if the majority of OHCA survivors live without psychological distress and with good self-assessed health, there are individuals that experience major problems. Consequently, it should be expected that some survivors will benefit from psychiatric rehabilitation, and survivors of young age, who are female, and those with treatment-requiring comorbidity should be screened early on.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. During the study period of 4 years, a specially trained nurse was placed at every hospital in a large region of Sweden. With this approach, we were able to collect data from virtually every case of OHCA. The study design also allowed us to match non-respondents with data collected from the SCRR at the time of their hospitalisation, thus enabling comparisons between respondents and non-respondents. Consequently, we were able to confirm that the study population represents the group at large in these aspects. Another strength is that the outcomes in this study could be compared with the average Swedish population. Knowledge regarding factors of importance for a psychological state and self-assessed health in line with the normal population after OHCA in Sweden is missing. This information will help to generalise the overall picture of OHCA survival and provide guidance regarding which survivors who need psychiatric rehabilitation. Furthermore, the response rate was very high at 12 months.

The main limitations of this study are the retrospective design and the restrictive inclusion of survivors with good neurological functioning (CPC-score ≤2), which limits the applicability on OHCA survivors more broadly. However, we made the assessment that inclusion of survivors with a severe cerebral dysfunction would complicate the interpretability of the results. Furthermore, it is not possible to differentiate between patients with a CPC-score of 1 and 2. However, as mentioned above, we lack knowledge of the minimal clinically important difference regarding the HADS and EQ-5D-3L in this population. The strict inclusion is also reflected by the relatively small sample size, resulting in a low count of events per variable in the logistic regression (five variables were evaluated in 70 participants), why the significance of these results should be interpreted with caution. Another methodical limitation in this study is the use of EQ-5D-3L to measure self-assessed health. A recent study concluded that EQ-5D-3L might underestimate the health in OHCA survivors, yielding high ceiling effects, which was apparent in the EQ-5D-3L descriptive system in this study as well.23 Although EQ VAS showed higher interpretability with a more varied outcome in our study population, it is known that generic measures of health often fail to capture the true complexity of the health state in survivors of cardiac arrest.37 Finally, some survivors were excluded due to severe illness and a few non-respondents mentioned poor health as the reason for not participating. Therefore, it is possible that the participants in this study had a better outcome than survivors more generally.

Conclusions

On a group level, there is a significant improvement in the psychological and health-related outcomes among survivors of OHCA between 3 and 12 months after resuscitation. Higher levels of psychological distress can be expected among female survivors and those with treatment-requiring comorbidity, while young and female survivors are at risk of a self-assessed poor health. These findings should be considered in the follow-up after OHCA, although future research is required to identify further predictors regarding the long-term outcome and chance of improvement postcardiac arrest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the dedicated nurses who contributed to our collection of data. We would also like to thank Dr Kate Bramley-Moore for English language editing assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made a substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study. AV analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. KSS and ÅA initiated and planned the study, collected the data, assisted in the interpretation of the data and took part in drafting the manuscript. JH took part in the planning of the study, contributed with external expertise and have continuously revised the manuscript. DJ helped to analyse the data and have continuously revised the manuscript.

Funding: Funding was provided as a grant from the Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board (VGFOUREG-78031), Region Västra Götaland, Sweden. The guarantor had no role in the design or execution of this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical permission was granted by the Regional Ethics Review Board, Western Sweden (no. 465–7). Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Due to ethical restrictions, data are available on request. Interested researchers may submit a request for data to the authors (adam.viktorisson@gu.se). According to Swedish regulation: http://www.epn.se/en/start/regulations/, the permission to use data is only for what has been applied for and then approved by the Ethical board. To not follow the regulations is seen as scientific misconduct.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Strömsöe A, Svensson L, Axelsson ÅB, et al. Improved outcome in Sweden after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and possible association with improvements in every link in the chain of survival. Eur Heart J 2015;36:863–71. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herlitz J. The Swedish national registry for cardiopulmonary resuscitation - Annual report 2017. Gothenburg 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nolan JP, Neumar RW, Adrie C, et al. post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. a scientific statement from the international liaison committee on resuscitation; the american heart association emergency cardiovascular care committee; the council on cardiovascular surgery and anesthesia; the council on cardiopulmonary, perioperative, and critical care; the council on clinical cardiology; the council on stroke. Resuscitation 2008;79:350–79. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lilja G, Nielsen N, Bro-Jeppesen J, et al. Return to work and participation in society after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e003566 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moulaert VR, Verbunt JA, van Heugten CM, et al. Cognitive impairments in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2009;80:297–305. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wachelder EM, Moulaert VR, van Heugten C, et al. Life after survival: long-term daily functioning and quality of life after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2009;80:517–22. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilder Schaaf KP, Artman LK, Peberdy MA, et al. Anxiety, depression, and PTSD following cardiac arrest: a systematic review of the literature. Resuscitation 2013;84:873–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Green CR, Botha JA, Tiruvoipati R. Cognitive function, quality of life and mental health in survivors of our-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a review. Anaesth Intensive Care 2015;43:568–76. 10.1177/0310057X1504300504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moulaert VRM, van Heugten CM, Gorgels TPM, et al. Long-term Outcome After Survival of a Cardiac Arrest: A Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2017;31:530–9. 10.1177/1545968317697032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lundgren-Nilsson A, Rosén H, Hofgren C, et al. The first year after successful cardiac resuscitation: function, activity, participation and quality of life. Resuscitation 2005;66:285–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sunnerhagen KS, Johansson O, Herlitz J, et al. Life after cardiac arrest; a retrospective study. Resuscitation 1996;31:135–40. 10.1016/0300-9572(95)00903-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Akahane M, Tanabe S, Koike S, et al. Elderly out-of-hospital cardiac arrest has worse outcomes with a family bystander than a non-family bystander. Int J Emerg Med 2012;5:41 10.1186/1865-1380-5-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sauvé MJ, Doolittle N, Walker JA, et al. Factors associated with cognitive recovery after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Crit Care 1996;5:127–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamphuis HC, De Leeuw JR, Derksen R, et al. A 12-month quality of life assessment of cardiac arrest survivors treated with or without an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Europace 2002;4:417–25. 10.1053/eupc.2002.0258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whitehead L, Perkins GD, Clarey A, et al. A systematic review of the outcomes reported in cardiac arrest clinical trials: the need for a core outcome set. Resuscitation 2015;88:150–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viktorisson A, Sunnerhagen KS, Pöder U, et al. Well-being among survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a cross-sectional retrospective study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021729 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet 1975;1:480–4. 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan PW, Slejko JF, Sculpher MJ, et al. Catalogue of EQ-5D scores for the United Kingdom. Med Decis Making 2011;31:800–4. 10.1177/0272989X11401031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, et al. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:13 10.1186/1477-7525-8-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrew E, Nehme Z, Bernard S, et al. Comparison of health-related quality of life and functional recovery measurement tools in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation 2016;107:57–64. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lisspers J, Nygren A, Soderman E, et al. HAD): some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 1997;96:281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 2001;10:621–35. 10.1023/A:1013171831202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Axelsson ÅB, Sunnerhagen KS, Herlitz J. Representativity and co-morbidity: Two factors of importance when reporting health status among survivors of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2016;101:44–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dougherty CM. Longitudinal recovery following sudden cardiac arrest and internal cardioverter defibrillator implantation: survivors and their families. Am J Crit Care 1994;3:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:70 10.1186/1477-7525-5-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Puhan MA, Frey M, Büchi S, et al. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:46 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lilja G, Nilsson G, Nielsen N, et al. Anxiety and depression among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation 2015;97:68–75. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.09.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Verberne D, Moulaert V, Verbunt J, et al. Factors predicting quality of life and societal participation after survival of a cardiac arrest: A prognostic longitudinal cohort study. Resuscitation 2018;123:51–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.11.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Magyar-Russell G, Thombs BD, Cai JX, et al. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in adults with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2011;71:223–31. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nolan JP, Soar J, Cariou A, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines for Post-resuscitation Care 2015: Section 5 of the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation 2015;95:202–22. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swedish Resuscitation Council - Post Cardiac Arrest Consult Team. Swedish guidelines for follow-up after cardiac arrest 2016.

- 35. Israelsson J, Lilja G, Bremer A, et al. Post cardiac arrest care and follow-up in Sweden - a national web-survey. BMC Nurs 2016;15:15:1 10.1186/s12912-016-0123-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Egerod I, Risom SS, Thomsen T, et al. ICU-recovery in Scandinavia: a comparative study of intensive care follow-up in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2013;29:103–11. 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haywood K, Whitehead L, Nadkarni VM, et al. COSCA (Core Outcome Set for Cardiac Arrest) in Adults: An Advisory Statement From the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation 2018;137:e783–e801. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.