Abstract

Background:

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) is a rapidly-progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by an abnormal isoform of the human prion protein. Structural MRI in pathologically-confirmed sCJD patients was compared to cognitively-normal individuals to identify a cortical thickness signature of sCJD.

Methods:

This retrospective cross-sectional study compared autopsy-confirmed sCJD patients with dementia (n=11) to age- and sex-matched cognitively normal individuals (n=22). We identified regions of interest (ROIs) in which cortical thickness was most affected by sCJD. Within sCJD patients, the relationship between ROI cortical thickness and clinical measures (disease duration, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau, and diffusion weighted imaging abnormalities) was evaluated.

Results:

Compared with cognitively normal individuals, sCJD patients had significantly reduced cortical thickness in multiple ROIs, including the fusiform gyrus, precentral gyrus, precuneus, and superior temporal gyrus bilaterally; the caudal middle frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, and transverse temporal gyrus in the left hemisphere; and the superior parietal lobule in the right hemisphere. Only one SCJD patient had co-pathology consistent with Alzheimer disease. Reduced cortical thickness did not correlate with disease duration, presence of diffusion restriction, or elevated CSF tau.

Discussion:

Cortical signature changes in sCJD may reflect brain changes not captured by standard clinical measures. This information may be used with clinical measures to inform the progression of sCJD and patterns of prion protein spread throughout the brain. These results may have implications for prediction of symptomatic progression and plausibly for development of therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Biomarker, Cortical thickness, Cortical signature, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Neurodegenerative disorders, Prion diseases, Rapidly progressive dementia

INTRODUCTION

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare, fatal, neurodegenerative disorder caused by abnormally folded human prion proteins (PrPSc). The misfolded protein propagates throughout the brain causing rapidly-progressive dementia and neurological dysfunction (1,2). While most cases arise sporadically (sCJD), inherited and acquired forms occur (3). The genotype at codon 129 of the PrP gene affects disease expression, including disease duration (4,5).

Early in the symptomatic course, sCJD can be difficult to differentiate from other rapidly-progressive dementias (6,7). This uncertainty often necessitates extensive evaluations (8). Currently, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measurements and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) assist in diagnosis (9,10). Elevated CSF 14–3-3 and tau are nonspecific markers of sCJD; the addition of CSF real-time quaking induced conversion (RT-QuIC) analyses, a more specific diagnostic measure, improves the accuracy of antemortem diagnoses (11,12). Complementing these laboratory measures, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) demonstrates restricted diffusion within the cortical ribbon with good diagnostic sensitivity and specificity (11,13). However, currently available CSF and MRI studies offer limited insight into brain topography affected in sCJD. Discerning this information in vivo may reveal vulnerable brain areas. Understanding sCJD from this perspective has applications for clinical counseling and care, and, potentially, for the development of therapeutic strategies aimed at arresting spread within the brain (14).

In vivo structural MRI may provide insight into areas vulnerable to sCJD. In other neurodegenerative diseases, grey matter atrophy represents some of the earliest changes (15). For example, a cortical thickness signature can differentiate Alzheimer disease (AD) from frontotemporal dementia (16,17). To explore whether this approach could be applicable to sCJD, we identified cortical thickness changes within regions of interest (ROIs) most affected by sCJD. We performed a cross-sectional study that compared autopsy-confirmed sCJD patients with dementia to age- and sex-matched cognitively normal individuals. Within the sCJD group, we evaluated relationships between regional brain thickness and clinical markers of disease (disease duration, CSF tau, and DWI abnormalities).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

sCJD patients were evaluated at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) (Barnes-Jewish Hospital; Saint Louis, MO) for rapidly progressive dementia from January 2009 to June 2016. We identified eleven individuals with an available MRI (scanned an average of 2.8 months after symptom onset) and who were pathologically proven to have sCJD (National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC); Cleveland, OH). CSF tau levels were measured in nine sCJD patients (NPDPSC; Cleveland, OH).

MRI scans were obtained from twenty-two healthy individuals (confirmed biomarker negative for amyloid and tau) from the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (WUSM; Saint Louis, MO). Cognitively normal individuals and cases were matched two-to-one according to age, sex, and scanner strength. Study protocols were approved by the WUSM Human Research Protections Office and the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Participants or their delegates provided written informed consent for participation.

Imaging Acquisition and Analysis

T1-weighted Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) images and DWI were acquired using similar MRI protocols. FreeSurfer v.5.1.0 was used for cortical surface reconstruction and volumetric segmentation (18). Cortical thickness was extracted for predefined FreeSurfer regions. To ensure adequate assignment of neuroanatomical labels, images were reviewed and manually edited when necessary. Cortical thickness measurements were obtained using the smallest distance (millimeters) from the white and grey matter boundary to the pial surface (19).

Pathology

Brain dissection and tissue processing was performed by a board certified pathologist (R.J.P.) in ten sCJD patients at WUSM using established protocols. Brains were bisected in the sagittal plane. Left hemibrains were preserved in buffered formalin; right hemibrains were sampled for histologic processing and subsequently frozen en bloc for Western blot analysis by the NPDPSC. Histologic sampling and/or review included the cortex and white matter from the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes, and sections from the hippocampus, striatum, thalamus, and cerebellum; for some cases, a smaller subset of areas was sampled. Tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 hours, treated with formic acid to denature the prion protein, processed, and embedded in paraffin.

Paraffin wax sections were mounted onto slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin allowed microscopic histomorphologic assessment of pathological features including: spongiform change, neuronal loss, gliosis, ‘balloon cells,’ prion plaques (cerebellar microplaques, kuru-like plaques, and florid plaques), amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, Lewy bodies, arteriolosclerosis, and infarction, among others. Immunohistochemistry was also performed, using anti-Aβ (10D5; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) and anti-phosphorylated tau (PHF-1; a gift from Dr. P. Davies, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY) antibodies, allowing more sensitive evaluation for beta-amyloid peptide deposits (i.e. diffuse and cored amyloid plaques, cerebral amyloid angiopathy) and for hyperphosphorylated tau pathology (e.g., neurofibrillary tangles, diffusely immunoreactive neurons [‘pre-tangles’], ‘balloon cells’, neuropil threads, neuritic plaques, coiled bodies, astrogliopathy [e.g. aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG)], and grains [of argyrophilic grain disease]). Co-pathologies can contribute to regional brain thickness changes and clinical markers of disease. When AD pathology was detected, the AD neuropathologic change (ADNC) criteria (20) was used, and in cases with limited sampling and/or without 10D5 and PHF-1 IHC, ADNC was estimated using available data. In ADNC scoring: “A” corresponds to the β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and is divided into A0, A1, A2, and A3 based on Thal phases; “B” represents the Braak stage of neurofibrillary tangles (B0, B1, B2, B3); and ‘C” refers to neuritic plaque score as determined by CERAD score (C0, C1, C2, C3).

The NPDPSC confirmed the neuropathologic diagnosis of prionopathy. Confirmatory studies performed by the NPDPSC included immunoblotting using frozen brain homogenates before and after proteinase K treatment (3F4 anti-prion antibody), and immunohistochemistry on formic acid-treated formalin-fixed paraffin embedded sections using anti-prion protein antibodies (e.g. 3F4). Prion protein gene (PRNP) sequencing (PCR amplification was followed by bi-directional sequence analysis using DNA from frozen brain tissue. This procedure was performed by the CLIA-certified Center for Human Genetics Laboratory of the University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio.

DWI Analysis

Two board-certified neurologists (B.M.A. and G.S.D.) independently reviewed axial DWI scans from sCJD participants to assess DWI abnormalities. A region was considered abnormal if the intensity in sCJD scans was higher than expected in cognitively normal individuals. Raters visually graded the signal intensity within eight predefined regions commonly affected by sCJD: caudate, frontal lobe, insula, occipital lobe, parietal lobe, putamen, temporal lobe, and thalamus (Supplemental Figure 1) (13). Signal was designated “absent”, “possibly present/mildly present”, or “strongly present” (scored “0”, “1” or “2” respectively). Inter-observer agreement was calculated using the kappa coefficient. Differences between raters were resolved through successive consensus discussions until agreement was achieved (Cohen’s kappa > 0.8). When disagreement persisted, the lowest regional score was selected, reflecting a conservative approach.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in regional cortical thickness between sCJD and cognitively normal controls were compared using paired student t-tests. False discovery rate (FDR) was applied to correct for multiple comparisons; p-value <0.005 was considered significant. Regional cortical thickness was compared to disease duration for sCJD participants.

A vertex-wise analysis was performed using QDEC, an application in FreeSurfer, to generate group difference maps for cortical thickness using a general linear model. Each participant was resampled to a common space (fsaverage) for group analysis (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/FsTutorial/QdecGroupAnalysis_freeview). Monte Carlo simulation was performed to correct for multiple comparisons using a strict vertex wise (cluster forming) threshold (p < 0.005).

We compared regional cortical thickness to CSF tau values and DWI scores using a general linear model. To determine whether a significant relationship was present, we calculated the Spearman correlation coefficient for each region.

RESULTS

The median age at time of imaging for sCJD participants was 65 years (range 52–75 years). Six sCJD participants were male (6/11, 55%). Memory impairment was the most frequent presenting symptom (7/11, 64%), followed by movement abnormalities (5/11, 45%) and language difficulties (2/11, 18%). Median disease duration (symptom presentation to death) was 91 days (range 50–440 days). For nine sCJD participants, median CSF tau levels were 2048 pg/mL (range 1528–13240 pg/mL). The median age of the twenty-two cognitively normal individuals was 65.5 years (range 51–76 years); twelve individuals were male (55%).

From the ten sCJD participants with available pathologic information, four did not exhibit additional co-pathologies. Five sCJD patients had low ADNC pathology suggesting normal aging or diseases other than AD (20). One participant had an intermediate ADNC, suggesting early AD-related changes. Using the ADNC criteria, co-pathologies did not contribute to observed changes in cortical thickness (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Demographics | Clinical | Pathology | Imaging | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

Sex | Disease Duration (days) |

Days from Symptom Onset to MRI | Variant | CJD Histologic Pattern* | Significant Copathology | Histology Sampling | Non-Prion IHC | Scanner Type | Scanner Strength (T) |

| 60 | F | 79 | 59 | VV1-2 | VV2 (and MV2, due to ‘kuru’ plaques); no balloon cells of VV1) | None | F, P, S, Cb | Siemens Avanto | 1.5 | |

| 75 | M | 86 | 58 | MM1 | MM1 | Limited sampling; Low ADNC (Estimated Braak NFT stage: I or II) | F, MTL, Cb | Siemens SymphonyTim | 1.5 | |

| 52 | F | 440 | 230 | MM2 | MM2 | None | F, O, MTL, S, Cb | Siemens SymphonyTim | 1.5 | |

| 74 | M | 139 | 43 | VV2 | VV2 | Low ADNC (A1, B1, C0) | Complete | 10D5, PHF-1 | Phillips Medical Systems Achieva | 3 |

| 63 | M | 179 | 162 | VV2 | VV2 | None | Complete | Siemens TrioTim | 3 | |

| 65 | F | 60 | 56 | MM1-2 | MM2 | None | Complete | Siemens TrioTim | 3 | |

| 52 | M | 245 | 154 | MV1 | Not available** | Not available** | Not available** | Siemens Avanto | 1.5 | |

| 65 | F | 50 | 46 | MM1 | MM1 | Low ADNC (A1, B1, C0); Arteriolosclerosis (mild-moderate) | Complete | 10D5, PHF-1 | Siemens TrioTim | 3 |

| 66 | F | 91 | 47 | VV2 | VV2 | Low ADNC (A1, B1, C0) | Complete | Siemens Skyra | 3 | |

| 74 | M | 67 | 63 | MM1 | MM1 | Intermediate ADNC (A2,B2,C1/2); CAA (mild); Arteriolosclerosis (mild-moderate) | Complete | 10D5, PHF-1 | Siemens TrioTim | 3 |

| 63 | M | 234 | 54 | MM2 | MM2 | Low ADNC (A1, B1, C0); CAA (mild-moderate) | Complete | 10D5, PHF-1 | Siemens Biograph mMR | 3 |

As described in Gambetti P et al, British Medical Bulletin 2003;66:213

Autopsy performed at an outside institution

IHC = immunohistochemistry; ADNC = Alzheimer disease neuropathologic change; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy

“Complete” = frontal lobe (F), temporal lobe (T), occipital lobe (O), mesial temporal lobe (MTL), striatum (S), thalamus (Th), and cerebellum (Cb); “P” = parietal lobe.

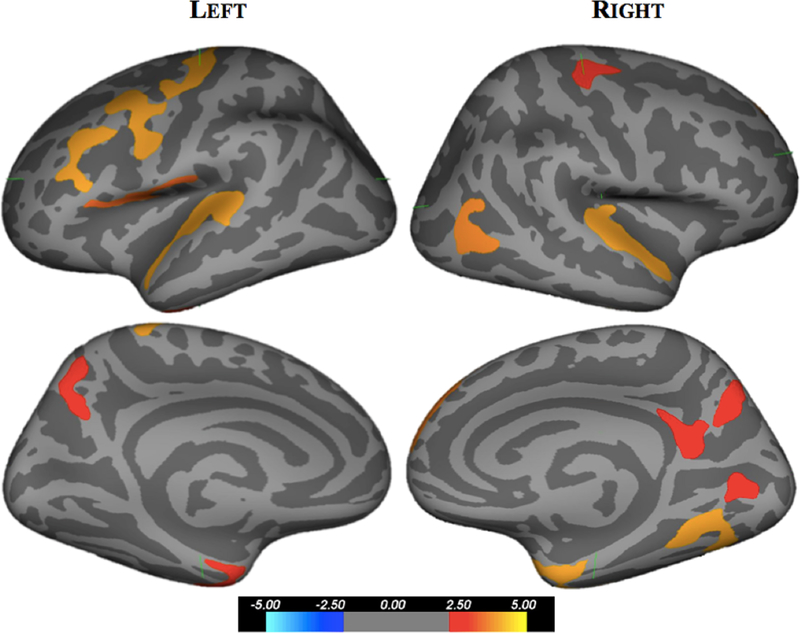

In general, brain cortical thickness was diffusely reduced in sCJD patients compared to cognitively normal individuals (Supplemental Table 1). The fusiform gyrus, precentral gyrus, precuneus, and superior temporal gyrus bilaterally; the caudal middle frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, and transverse temporal gyrus in the left hemisphere; and the superior parietal lobule in the right hemisphere were significantly thinner in sCJD patients than cognitively normal individuals (p<0.005) (Figure 1). The left hemisphere was more affected; cortical thinning was reduced in nine ROIs compared to five in the right hemisphere. Disease duration did not correlate with cortical thickness changes in sCJD.

Figure 1.

Cortical thickness difference map comparing sCJD patients to cognitively normal individuals. Regions with significant loss of cortical thickness are presented on lateral and medial views of an inflated brain with values on color scale representing -log10(p value). Significant reductions in brain thickness were seen within frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes of sCJD participants compared to cognitively normal individuals.

We also evaluated the relationship between cortical thickness and typical clinical measures. Excellent agreement concerning DWI abnormalities was achieved following two rounds of review (Cohen’s kappa, 0.91; p <0.001). DWI abnormalities were identified in the insula of 86% (left: 10/11, right: 9/11); frontal and temporal lobes of 82% (left: 9/11, right: 9/11); parietal lobe of 77% (left: 8/11, right: 9/1); occipital lobe of 64% (left: 7/11, right: 7/11); caudate of 59% (left: 6/11, right: 6/11); putamen of 50% (left: 5/11, right: 6/11); and thalamus of 41% (left: 4/11, right: 5/11) of sCJD participants. We correlated the strength of DWI signal abnormalities, as determined by the raters, with quantitative cortical thickness measurements from corresponding regions. No correlations were detected between DWI metrics and brain ROI cortical thickness measurements. CSF tau also did not correlate with regional cortical thickness measurements.

DISCUSSION

Cortical thickness was reduced in sCJD patients compared to cognitively normal individuals. Changes in cortical thickness were similar across disease durations, which could suggest that sCJD follows a common pathway. Only one sCJD patient had early AD pathology. Brain cortical thickness measurements did not correlate with known biomarkers of sCJD (DWI abnormalities or CSF tau), suggesting that brain cortical thickness measurements provide additional information concerning sCJD patients.

Cortical thickness decreases due to sCJD were most frequent within the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes. Recognizing these regions are integral to memory retrieval/encoding, language perception/processing and movement, it is plausible that early pathologic changes within these areas (resulting in atrophy at the time of imaging) may account for the high prevalence of cognitive, behavioral, and motor complaints early in the symptomatic course (21). Diffuse regions are typically affected volumetrically as well, showing decreases in the caudate, putamen, thalamus, hippocampus, insula, inferior frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, and middle temporal gyrus (22).

Interestingly, the cortical signature of sCJD is similar to that reported in individuals with symptomatic AD (16). The greatest degree of cortical changes in individuals with early-symptomatic AD are reported in the temporal and parietal lobes, with minimal early changes in the frontal lobe (16). Further studies are needed to investigate the temporal progression of change in individuals with sCJD. A common method of propagation of pathology may occur via highly conserved neural networks in neurodegenerative diseases.

DWI abnormalities did not correlate with cortical thickness changes in sCJD. The lack of relationship between DWI changes and neurodegeneration may be attributed to the severity of neurodegeneration, recognizing that regions with the greatest cortical atrophy may not have sufficient neurons to generate the typical pattern of restricted diffusion observed in sCJD. If this is the case, DWI changes would be expected to precede regional volumetric changes - a hypothesis that could be evaluated through longitudinal neuroimaging studies.

Finally, we investigated whether a widely-used biomarker, CSF tau, could predict the degree of atrophy observed in sCJD patients. We hypothesized that elevated CSF tau would correlate with decreased thicknesses in the ROIs. However, thickness values were not correlated with CSF tau levels, despite overall increased CSF tau. We conclude that CSF tau does not reflect regional thickness decreases associated with sCJD. PET molecular tracers have been identified allowing tau deposition to be mapped and quantified within the brains of living patients, but their application in mapping brain areas undergoing active neurodegeneration in sCJD is limited (23–25). In a separate study of sCJD participants, we did not observe increased tau deposition (23). Thus, taken together, our results further support that CSF tau may be a non-specific measure of neuronal degeneration in individuals with sCJD.

This study exhibits several strengths. Our focus on sCJD, rather than a mixed population, and rigorous matching of cases and cognitively normal individuals, minimized the effect of confounders on reported relationships. Additionally, all participants had pathologically-proven sCJD, imparting diagnostic confidence. However, there are limitations that could affect the interpretation of these results. Although WUSM is a regional referral center for sCJD, the rarity of the disease (approximately one per one million per year) and requirement of MRI for volumetric imaging limited inclusion in this study (26). Consequently, we were unable to consider differences in the cortical signature between sCJD subtypes. Underlying co-pathologies may limitedly influence cortical thickness data (Table 1). Future studies enrolling larger numbers of patients are needed to establish the cortical signature in subsets of patients with sCJD and to facilitate testing of hypotheses specific to the spread of PrPSc.

Despite these limitations, our findings may inform clinical practice. We suggest that cortical thinning may depict vulnerable areas in sCJD. If the cortical signature defining early-symptomatic phases of this disease can be identified, routine brain MRI may be leveraged to improve recognition and diagnosis of sCJD. Earlier recognition would offer dual advantages: permitting earlier intervention when rational therapeutic options are available (reminiscent to strategies currently being investigated in AD (27)); providing an additional biomarker to longitudinally follow in sCJD individuals, allowing for mapping the spread of disease.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Cortical thicknesses for predefined regions and associated p-values for sCJD patients and cognitively normal individuals. Bold values indicate p<0.005.

Supplemental Figure 1. Axial diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) showing pathologic hyperintensities in eight anatomical regions of interest (ROIs): A) caudate, putamen, insula, thalamus; and B) frontal lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe; C) temporal lobe.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was funded by NIH grants R01NR012907, R01NR012657, R01NR014449, P50AG05681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, P30NS048056, UL1TR000448, and R01AG04343404. Funding was also provided by the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Research Initiative, the Hope Center for Neurological Disorders, the Washington University in Saint Louis Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences (ICTS), and generous support from the Paula and Rodger O. Riney Fund and the Daniel J Brennan MD Fund.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Jaimie Navid, Robert Bucelli, David Soleimani-Meigooni, Aylin Dincer, Richard Perrin, Julie Wisch, and Beau Ances report no conflict of interest. Gregory Day reports personal fees from DynaMed, non-financial support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, grants from NIH, BJH Foundation/ICTS research, and the American Brain Foundation. He is currently participating in clinical trials sponsored by Eli Lilly and Biogen. He holds stocks (>$10,000) in ANI Pharmaceuticals. Jeremy Strain reports grants from NIH during the conduct of the study. John Morris reports grants P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, and UF01AG032438 from NIH during the conduct of the study. He reports clinical trials and research support from Eli Lilly, Biogen, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Tammie Benzinger reports grants from Avid Radiopharmacueticals (Eli Lilly) and clinical trials from Eli Lilly, Roche, Janssen, and Biogen outside the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris DA. Cellular biology of prion diseases. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1999;12(3):429–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masters CL, Richardson EP. Subacute spongiform encephalopathy (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease): The nature and progression of spongiform change. Brain. 1978;101(2):333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill AF. Molecular classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2003;126(6):1333–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parchi P, Castellani R, Capellari S, et al. Molecular basis of phenotypic variability in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Annals of Neurology. 1996;39(6):767–778. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8651649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cali I, Castellani R, Yuan J, et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease revisited. Brain. 2006;129(9):2266–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skillbäck T, Rosén C, Asztely F, Mattsson N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Diagnostic performance of cerebrospinal fluid total tau and phosphorylated tau in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Results from the Swedish mortality registry. JAMA Neurology. 2014;71(4):476–483. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Everbroeck B, Dobbeleir I, De Waele M, De Deyn P, Martin J-J, Cras P. Differential diagnosis of 201 possible Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients. Journal of Neurology. 2004;251(3):298–304. 10.1007/s00415-004-0311-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day GS, Tang-Wai DF. When dementia progresses quickly: a practical approach to the diagnosis and management of rapidly progressive dementia. Neurodegenerative Disease Management. 2014;4(1):41–56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24640978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schröter A, Zerr I, Henkel K, Tschampa HJ, Finkenstaedt M, Poser S. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Clinical Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Archives of Neurology. 2000;57(12):1751 http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archneur.57.12.1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermann P, Laux M, Glatzel M, et al. Validation and utilization of amended diagnostic criteria in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease surveillance. Neurology. 2018;91(4):331–338. http://n.neurology.org/content/91/4/e331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdulmassih R, Min Z. An ominous radiographic feature: cortical ribbon sign. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2016;11(2):281–283. 10.1007/s11739-015-1287-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atarashi R, Sano K, Satoh K, Nishida N. Real-time quaking-induced conversion: A highly sensitive assay for prion detection. Prion. 2011;5(3):150–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young GS, Geschwind MD, Fischbein NJ, et al. Diffusion-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2005;26:1551–1562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telling CG, Parchi P, Dearmond S, et al. Evidence for the Conformation of the Pathologic Isoform of the Prion Protein Enciphering and Propagating Prion Diversity. Science. 1997;24:2079–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caverzasi E, Mandelli ML, DeArmond SJ, et al. White matter involvement in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2014;137(12):3339–3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickerson BC, Bakkour A, Salat DH, et al. The Cortical Signature of Alzheimer’s Disease: Regionally Specific Cortical Thinning Relates to Symptom Severity in Very Mild to Mild AD Dementia and is Detectable in Asymptomatic Amyloid-Positive Individuals. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(3):497–510. 10.1093/cercor/bhn113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du AT, Schuff N, Kramer JH, et al. Different regional patterns of cortical thinning in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2007;130(4):1159–1166. 10.1093/brain/awm016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage. 2006;31(3):968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(20):11050–11055. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC27146/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia. Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2012;8(1):1–13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22265587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabinovici GD, Wang PN, Levin J, et al. First symptom in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Neurology. 2006;66(2):286–287. http://n.neurology.org/content/66/2/286.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Vita E, Ridgway GR, White MJ, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of prion disease progression - a 3T longitudinal voxel-based morphometry study. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2017;13:89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Day GS, Gordon BA, Perrin RJ, et al. In vivo [18F]-AV-1451 tau-PET imaging in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2018;90(10):896–906. http://n.neurology.org/content/90/10/e896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brier MR, Gordon B, Friedrichsen K, et al. Tau and Aβ imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8(338):338 http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/8/338/338ra66.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon BA, Friedrichsen K, Brier M, et al. The relationship between cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer pathology and positron emission tomography tau imaging. Brain. 2016:139(8):2249–2260. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4958902/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holman RC, Belay ED, Christensen KY, et al. Human prion diseases in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisoni GB, Boccardi M, Barkhof F, et al. Strategic roadmap for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology. 2017;16:661–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gambetti P, Kong Q, Zou W, Parchi P, Chen SG. Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;66(1):213–239. 10.1093/bmb/66.1.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Cortical thicknesses for predefined regions and associated p-values for sCJD patients and cognitively normal individuals. Bold values indicate p<0.005.

Supplemental Figure 1. Axial diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) showing pathologic hyperintensities in eight anatomical regions of interest (ROIs): A) caudate, putamen, insula, thalamus; and B) frontal lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe; C) temporal lobe.