Abstract

The RNA-activated protein kinase, PKR, is a key mediator of the innate immunity response to viral infection. Viral double-stranded RNAs induce PKR dimerization and autophosphorylation. The PKR kinase domain forms a back-to-back dimer. However, intermolecular (trans) autophosphorylation is not feasible in this arrangement. We have obtained PKR kinase structures that resolves this dilemma. The kinase protomers interact via the known back-to-back interface as well as a front-to-front interface that is formed by exchange of activation segments. Mutational analysis of the front-to-front interface support a functional role in PKR activation. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that the activation segment is highly dynamic in the front-to-front dimer and can adopt conformations conducive to phosphoryl transfer. We propose a mechanism where back-to-back dimerization induces a conformational change that activates PKR to phosphorylate a “substrate” kinase docked in a front-to-front geometry. This mechanism may be relevant to related kinases that phosphorylate the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF2α.

Introduction

The RNA activated kinase, PKR, plays a pivotal role in antiviral defense1–3 and has also been implicated in cell cycle regulation4, metabolic disorders5,6, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer7–9. The importance of PKR is underscored by the elaborate and diverse strategies viruses have evolved to inhibit its activity10,11. Activation of PKR upon binding to viral RNAs induces autophosphorylation at a conserved threonine residue lying within the activation segment of the kinase domain. The activated enzyme then phosphorylates its major substrate, the translational initiation factor eIF2α. The resulting translational arrest blocks viral replication. PKR belongs to a conserved family of four protein kinases (PKR, PERK, GCN2, HRI) that all phosphorylate eIF2α in response to different stimuli12, triggering the integrated stress response13. In the case of PKR, the regulatory region consists of two tandem dsRNA binding domains. The regulatory region is separated from the C-terminal kinase domain by an unstructured linker.

Dimerization plays a key role in the activation of PKR by RNA3. A minimum length of 30 bp of dsRNA is required to bind two PKRs and to activate autophosphorylation14,15. PKR dimerizes weakly in solution (Kd ~ 500 μM), inducing activation at high concentration in the absence of RNA16. A crystal structure of a complex of phosphorylated PKR kinase and eIF2α revealed that the kinase has the typical bilobal structure and forms a back-to-back (BTB) dimer mediated by the N-lobes17. The interfacial residues are highly conserved amongst eIF2α kinases and mutagenesis implicates the BTB dimer in PKR function18. FRET measurements demonstrate that the kinase domains dimerize when PKR binds to activating dsRNAs19. These observations support a model where activating RNA serves as a scaffold to bind multiple PKR monomers, increasing the local concentration to enhance kinase dimerization. A similar kinase dimer architecture is found in PERK20, IRE121, RNase L22, NEK723 and in the Ser/Thr kinases PknB24,25, PknD26 and PknE27 from M. tuberculosis.

Protein kinases are highly regulated modules that switch between inactive and active conformations in response to signals such as ligand binding, phosphorylation, or interaction with protein binding partners. A key regulatory element is helix αC in the N-lobe, which typically undergoes displacement in the inactive to active transition. The BTB interface of the PKR kinase dimer incorporates a large region of helix αC; thus, this element may serve to link formation of the dimer with an inactive-to-active conformational transition. A recurring theme in kinase activation is the inter- or intra-molecular binding to a hydrophobic patch on the N-lobe that induces reorientation of helix αC28. In fact, dimerization-induced activation is widespread across the kinome29.

Several studies indicate that PKR autophosphorylation occurs via an intermolecular (trans) mechanism16,30–34 [for a contrary view see35]. The BTB dimer orients the active sites away from the dimer interface in a configuration that cannot mediate this reaction. Here, we report structures of wild-type, unphosphorylated PKR kinase. The kinase domains interact via the BTB interface and adopt an active conformation in the absence of activation loop phosphorylation. Our structure also reveals a novel, front-to-front (FTF) interface that is formed by activation loop exchange. Mutational analysis and molecular dynamics simulations support a model where this interface facilitates PKR trans-autophosphorylation.

Materials/Experimental Details

Protein expression and purification.

229-kinase construct encompassing residues 229–551 of human PKR (Uniprot ID P19525.2) was produced as by expression of full length enzyme16,36 containing a TEV protease cleavage site at residue 229, as previously described37. Full-length PKR was treated with TEV protease overnight at 4 °C. The 229-kinase cleavage product was purified on a CHT hydroxyapatite column (Biorad) using a 40–400 mM KH2PO4 gradient at pH 7.0 in the presence of 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol. TEV protease was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific or was expressed as a His-tagged construct38. Immediately prior to use, 229-kinase was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on Superdex 75 or 200 HiLoad 16/60 columns (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 75 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM TCEP. The S462A and G466L mutants were purified using the same protocol and eluted from the size exclusion column at a similar position as wild-type PKR kinase. Proper folding of the mutants was verified by dynamic light scattering.

Crystallization, Data collection and Structure Determination.

The apo form was crystallized by mixing 3 μL 10 mg/ml 229-kinase containing a 3-fold molar excess of heparin hexasaccharide with 1 μL crystallization solution containing 0.1 M Bis-Tris pH 5.5 and 2.0 M ammonium sulfate using hanging drop vapor diffusion at 20°C. The crystals were cryoprotected in sodium malonate (between 1.5 – 1.7 M final concentration) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. A complete dataset was collected to 3.1 Å at the FMX (17-ID-2) beam line at NSLS-II. The AMPPNP complex was prepared by adding 10 mM AMPPNP and 10 mM Mg2+ to 10 mg/ml 229-kinase and was crystallized by mixing 3 μL protein with 1 μL crystallization solution consisting of 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 6–7 % v/v PEG-400, and 2.0 M ammonium sulfate followed by hanging drop or sitting drop vapor diffusion at 20 °C. Crystals were cryoprotected by adding 2 M LiSO4 to the drop and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. A 2.6 Å dataset was collected at SSRL beamline 14–1.

Data were processed using iMosflm and scaled with Aimless in the CCP4i2 suite39,40. Phases were solved by molecular replacement with PHASER41 using the phosphorylated, AMPPNP-bound PKR kinase domain as the search model (molecule B, PDB id code 2A1917). Rebuilding was performed in COOT42 and refinement was done using Refmac543. The data statistics and final structure quality are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics.

| Apo | AMPPNP Complex | |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| Beam line | FMX, NSLS-II | 14–1, SSRL |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9790 | 0.9795 |

| Space group | P 61 2 2 | C 2 2 21 |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 92.69 92.69 123.33 | 106.48, 159.60, 172.99 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 123.33–3.10 (3.10–3.181) | 172.99–2.6 (2.6–2.667) |

| Molecules/ASU | 1 | 3 |

| Rmeas | 0.268 (0.070) | 0.098 (0.034) |

| l/σl | 9.1 (3.2) | 9.4 (0.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 97.1 (98.1) |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 25.9 / 34.7 (38.3 / 38.6) | 20.9 / 27.3 (39.9/40.5) |

| Reflections Unique / Free | 5801 / 296 (410 / 16) | 42,089 / 2245 (3,154 / 157) |

| r.m.s deviations from ideal | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0108 | 0.013 |

| Angles (°) | 1.560 | 1.774 |

| B-factor analysis (overall) | ||

| Molecule A (Å2) | 89.8 | 78.8 |

| Molecule B (Å2) | - | 86.8 |

| Molecule C (Å2) | - | 92.6 |

| Model | ||

| Nonhydrogen atoms | 2046 | 6480 |

| Water molecules | - | 52 |

| Metals | - | 1Mg2+ |

| Ligands | - | ADP, 1 PO4, 7 SO4 |

Activity Assays.

PKR autophosphorylation was monitored by incorporation of 32P from [γ−32P]ATP (Perkin-Elmer) as previously described37. Reactions contained 200 nM PKR and variable concentrations of dsRNA activator (poly(rI:rC), GE Healthcare). Reactions were quenched with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS and spotted on 0.45 μm nitrocellulose filters (GE Healthcare). The filters were washed with 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, pH 8.0. The filters were exposed to a phosphor screen and 32P was quantified on a Typhoon phosphorimager using ImageQuant TL Software (GE Healthcare).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

Unresolved regions of the structure of the PKR kinase-AMPPNP complex were modeled in order to perform MD simulations. Residues 256–257, 441–450, and 335–355 from chain A, 255, 334–355, and 439–451 from chain B, and 334–356, 441–444, and 449 from chain C were inserted and Prime version 1 (Schrödinger, LLC)44 was used to generate a configuration of the missing loops. The complete models were energy-minimized with Desmond (Schrödinger, LLC)45 using the OPLS3 forcefield46 for 1,460 steps. ATP was modeled into the active site by superposition with the bound ADP using UCSF-Chimera version 447 and manual adjustment using Maestro version 5 (Schrödinger, LLC).

MD simulations of complete kinase domain dimers were prepared and run using the GROMACS 2016 package48. 1 μs simulations were performed in the NPT ensemble for FTF (chains A and B) and BTB (chains B and C) dimers using the CHARMM36m forcefield49. In both cases, a cubic box was used. The boxes were solvated with the CHARMM TIP3P water model and 150 mM NaCl. The total solvated system sizes for the FTF and BTB simulations were 134,834 atoms and 137,567 atoms, respectively. Both systems were energy minimized using a steepest-descent integrator; the FTF system converged after 1,322 steps, and the BTB system converged after 1,787 steps. The systems underwent 100 ps of NVT equilibration at 300 K, followed by a further 100 ps of NPT equilibration (300 K) at 1 atm. A velocity rescaling stochastic thermostat50 with a 0.1 ps time constant was employed for temperature coupling. Parinello-Rahman51 pressure coupling was used to isotropically maintain the system at 1.0 bar, with a time constant of 2.0 ps. The minimization, equilibration, and production simulations employed particle mesh Ewald for long range (>10 Å) electrostatics with a Fourier spacing of 1.6 Å. Short-range van der Waals and electrostatic interactions were smoothly shifted to zero at a cutoff distance of 10 Å. A leap-frog MD integrator was used for the production simulation, with a time step of 2 fs.

The first 50 ns of data was considered further equilibration and was not included in analyses. RMSD (root mean square deviation), COM (center of mass) buried surface area, and atom-atom distances analyses were performed using GROMACS 2016 tools. RMSD and COM calculations excluded the highly dynamic kinase-insert loops (residues 333–355) and activation loops (residues 432–465). The RMSD calculations were performed on the backbone atoms and used the initial frame of each simulation as the reference structure. Buried surface areas were determined using a Shrake-Rupley algorithm52 with a 1.4 Å probe radius.

Figures were made in PyMOL version 2.2.0 (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC).

Results

Oligomeric Assemblies

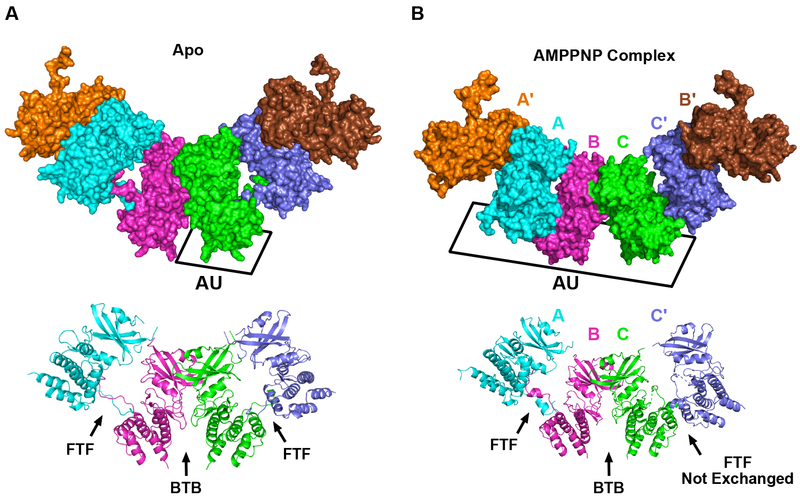

Crystallization trials of a wild-type, unphosphorylated PKR kinase construct (242–551) and a construct including a previous-defined37 basic region (229–551) yielded several crystal forms. Crystals of the 229–551 construct (apo) diffracted to 3.1 Å and those obtained in the presence of adenosine-5′-(β,γ-imido)triphosphate (AMPPNP) diffracted to higher resolution (2.6 Å). The structures were obtained in different space groups with a single monomer in the asymmetric unit for the apo form compared to three monomers in the nucleotide-bound form (Table 1). Nonetheless, the overall pattern of intermolecular interactions in the two lattices are remarkably similar. The kinase domains form alternating BTB and front-to-front (FTF) contacts that produces an extended, filament-like assembly within both crystals (Figure 1). In the apo structure, the BTB interface lies on a two-fold symmetry axis and is mostly contributed by the N-lobes. It closely resembles the dimer interface observed in the co-crystal structures of PKR kinase and eIF2α17 and a structure of an inactive PKR kinase53. The novel FTF interface principally involves the C-lobes and is formed by domain swapping where the activation segment is inserted into the reciprocal protomer. In the nucleotide complex, the asymmetric unit contains three monomers, labeled A, B, and C, generating four interfaces. The B:C and A:Aʹ interactions form similar BTB dimers. The FTF A:B interface involves exchanged activation loops, as observed in the apo structure. In the C:Cʹ interface, the two subunits adopt a different FTF orientation which does not exchange activation loops. The largest interface is the FTF with exchange, which contributes 1215–1248 Å2 of buried surface area per molecule (Table 2). The FTF interface without exchange is 871 Å2 and the BTB interfaces range from 818 to 958 Å2. None of the interfaces resemble the FTF interface reported by Li and coworkers53, which involves both N- and C-lobes and comprises only 432 Å2.

Figure 1. Arrangement of PKR kinase monomers in two crystal forms.

The top panels show a surface representation and the bottom panels show a cartoon representation. The alternating interfaces form a continuous, filament-like assembly within the crystal lattices. For clarity, only six protomers are shown in surface representation and three are shown in cartoon representation to illustrate the unique interfaces.

A) Apo crystal form. B) AMPPNP complex crystal form. One protein chain occupies the asymmetric unit (AU) in the apo crystal form. Three protein chains, labeled A, B, and C, are in the AU in the AMPPNP complex. The face-to-face (FTF) and back-to-back (BTB) interfaces are indicated in the cartoon representation of each structure. Each of the FTF interfaces involves exchange of activation segments except for the C-C chains, la.

Table 2.

Analysis of interfaces.

| Structure | Chains | Description | Buried Surface Area (Å2)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apo | A:A’ | FTF exchange | 1215 |

| Apo | A:A’ | BTB | 958 |

| AMPPNP | A:B | FTF exchange | 1248 |

| AMPPNP | C:C’ | FTF no exchange | 871 |

| AMPPNP | B:C | BTB | 857 |

| AMPPNP | A:A’ | BTB | 818 |

Buried surface area per molecule was calculated with PISA.78

Architecture of the Kinase Domains

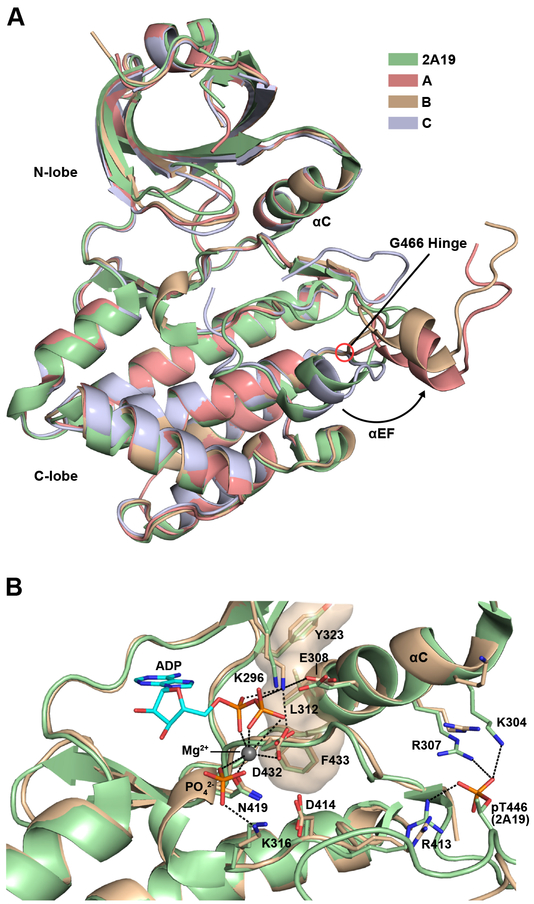

Further structural analysis will focus on the nucleotide complex owing to the significantly higher resolution of this structure. Figure 2A shows the structures of the three unique protomers in the asymmetric unit superimposed on the structure of an active, phosphorylated PKR kinase (PDB 2A19)17. The eIF2α kinases possess a characteristic insert lying between β4 and β5 (Fig. S1). This region is disordered in both constructs. PKR and other eIF2α kinases contain a slightly elongated αG helix which is displaced from the canonical position occupied in other kinases17,20. This helix forms the docking site for eIF2α17. Thus, it is noteworthy that helix αG occupies that same position in the absence of substrate. As is typical of structures of unphosphorylated protein kinases, portions of the activation loop are disordered (A: 441–450, B:440–450), but in chain C a shorter region is disordered (447–449). The RMS deviation between chains A and B is low (1.37 Å) but is substantially higher (~5.2 Å) when they are compared to chain C (Table 3). However, the deviations between the three chains drops to about 1.1 Å when the activation segment is removed from the alignment. Each of the chains align well with the phosphorylated kinase when the activation segment is excluded (Table 3). In chains A and B which undergo domain swapping, helix αEF swings out away from the body of the kinase domain to extend the activation segment outward to interact with the reciprocal protomer. In chain C, helix αEF adopts an inward-facing conformation similar to phosphorylated PKR. The two families of structures diverge between the DFG motif at the N-terminus of the activation segment and G466 located between helices αEF and αF.

Figure 2. Structural comparison of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated PKR kinase.

A) Alignment of the three unique protomers present in the asymmetric unit of the AMPPNP complex of the unphosphorylated PKR kinase domain with the AMPPNP complex of a phosphorylated PKR kinase domain (PDB 2A19, chain B). The color scheme is indicated in the legend. B) Comparison of the active sites. For clarity, only chain B of the unphosphorylated AMPPNP complex is shown. The nucleotide, free phosphate, and important side chains are rendered as sticks. The Mg2+ is indicated as a sphere. Hydrogen bond and salt-bridge interactions in the unphosphorylated kinase are denoted as dotted lines. The R-spine is shown in surface representation. A superposition of all three chains of the unphosphorylated enzyme with phosphorylated PKR kinase domain is shown in Figure S2.

Table 3.

Structure-based alignmenta

| Chain | Chain | RMSDb | RMSD without Activation Segmentc |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | 1.37 | 1.06 |

| A | C | 5.15 | 0.94 |

| B | C | 5.19 | 1.07 |

| A | Phospho-PKR kinased | 5.24 | 1.04 |

| B | Phospho-PKR kinased | 5.27 | 1.13 |

| C | Phospho-PKR kinased | 1.90 | 1.22 |

Structure-based alignment of the three subunits of the PKR-AMPPNP complex performed using PYMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.2.0), Schrödinger, LLC).

Root-mean square deviation of the aligned atoms (Å).

Root-mean square deviation of the aligned atoms omitting the activation segment residues 439–466 (Å).

PKR kinase domain phosphorylated on residue T446 corresponding to chain B of the PKR kinase – eIF2α crystal structure PDB ID 2A19. 17

Figure 2B shows a superposition of the active sites of unphosphorylated (chain B, gold), and the previously-reported phosphorylated (2A19, green) PKR structure. The unphosphorylated enzyme adopts an active conformation and superimposes closely with the active phosphorylated kinase. Helix αC is oriented such that the E308-K296 salt bridge is formed, positioning K296 to stabilize the bound nucleotide for catalysis. D432 coordinates the Mg2+ in a DFG-in conformation54. The regulatory spine, corresponding to F433, L312 and Y323 in PKR, is complete, a characteristic of active kinase structures55. The structures of the two other active sites are similar to protomer B (Figure S2). In the phosphorylated kinase, R413 from the HRD motif coordinates with pT446 and stabilizes the activation loop. pT446 is further stabilized by K304 and R307 providing a linkage between the activation loop and helix αC. These interactions cannot form in the unphosphorylated kinase and the corresponding side chains adopt alternative conformations.

Although the kinase was crystallized in the presence of AMPPNP and Mg2+, the electron density in the nucleotide binding pocket was best modeled with an ADP, a Mg2+, and a phosphate (Fig. 2B). The ADP α- and β-phosphates are coordinated by K296, a bound Mg2+, D432, and G279. It is likely that the nucleotide underwent hydrolysis during crystallization and the phosphate remained bound to the active site, as has been previously observed for protein kinase A (PKA)56. In the PKA structure, the free phosphate is close to the position that is occupied by the γ-phosphate of ATP. In the present structure the phosphate is displaced by about by 4 Å but remains bound to the Mg2+ and K316.

In the structure of phosphorylated PKR kinase containing an intact AMPPNP, two magnesium ions are bound, MgI and MgII, but only one is bound to the inactive structures in the same position as MgII. This agrees with previous studies of PKA where release of MgI occurred coincident with phosphoryl transfer57.

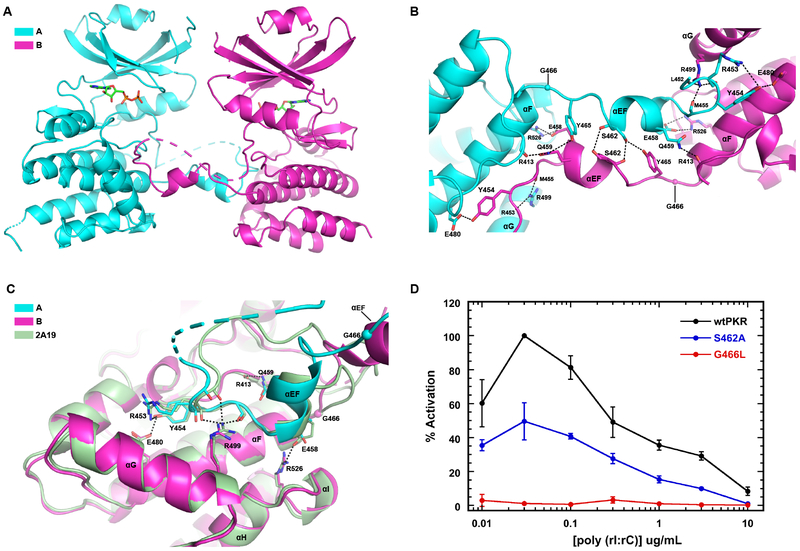

FTF Interface with Exchange

The most provocative interaction is the FTF interface with exchanged activation segments formed between chains A and B. The activation segments are inserted into the complementary protomer, suggesting an activation mechanism where T446 is phosphorylated in trans. The interface is created by docking of helix αEF and adjoining portions of the activation segment into the cleft formed between helices αF, αG, and αI on the opposite protein chain (Figs. 3A, 3B).

Figure 3. Analysis of the PKR kinase face-to-face dimer with exchange of activation loops.

A) Structure of the interface. The A and B chains of the AMPPNP complex of PKR kinase are depicted using the color scheme from Figure 1. The protomers are indicated in cartoon representation with the disordered regions of the activation loop and the C-terminus shown as dashes. The bound nucleotide is depicted in stick representation. B) Detailed view of the interactions stabilizing the interface. Key side chain and main chain atoms are rendered as sticks. Hydrogen bond and salt-bridge interactions are denoted by dashed lines. G466 is shown as a sphere. C) Structural alignment of a monomeric, phosphorylated PKR kinase (2A19) onto chain B forming a domain-swapped FTF dimer with chain A. The side chain and main chain atoms involved in polar interactions at the interface are rendered as sticks. D) Effect of interface mutations on PKR activation. The PKR autophosphorylation activity was assayed as a function of dsRNA concentration. The data are normalized to the maximal activation of wild-type PKR.

Many of the contacts made by the activation segment in monomeric PKR kinase are recapitulated within the FTF dimer (Fig. 3C). Domain-swapped kinases often contain a glycine or proline residue at the “hinge” position in the loop between helices αEF and αF58. PKR contains a conserved glycine at the hinge location (G466). The only polar interactions found exclusively in the FTF exchanged dimer are a pair of symmetrical hydrogen bonds between the side chain hydroxyls of each S462 and the reciprocal backbone carbonyl oxygens (Fig. 3B). R526 from the loop between αJ and αI anchors the C-terminal portion of the activation loop by forming a salt bridge with E458 at the base of αEF. Q459 stabilizes the HRD motif by a hydrogen bond to the main chain carbonyl of R413. The tip of the activation segment is stabilized by a hydrogen bond between Y454 and E480 from αF. In the FTF dimer, Y465 assumes two different conformations. In protomer B, it is oriented toward the side chain of S462 from protomer A. On the opposite side of the interface, Y465 from protomer A participates in a hydrogen bond interaction with Q459 in protomer B (Fig. 3B).

The mechanistic relevance of activation loop exchange was probed by assaying the functional effects of mutations to selectively disrupt activation segment exchange. PKR autophosphorylation induced by dsRNA shows a characteristic bell-shaped profile where the inhibition observed at high concentration is due to dissociation of PKR dimers by excess dsRNA (Fig. 3D). The S462A mutation disrupts hydrogen bonds exclusively found in the FTF interface with exchange and decreases the maximal extent of activation by about two-fold. In SPAK kinase, introduction of a bulky residue at the glycine hinge prevents refolding of the activation segment to an extended conformation and disrupts the FTF dimer58. Similarly, the G466L hinge mutation in PKR essentially abolishes dsRNA-induced autophosphorylation, supporting a functional role for the FTF exchange interaction in the activation process. Note that it was not feasible to examine the effects of these mutations on PKR dimerization due to interference from the BTB dimer interaction.

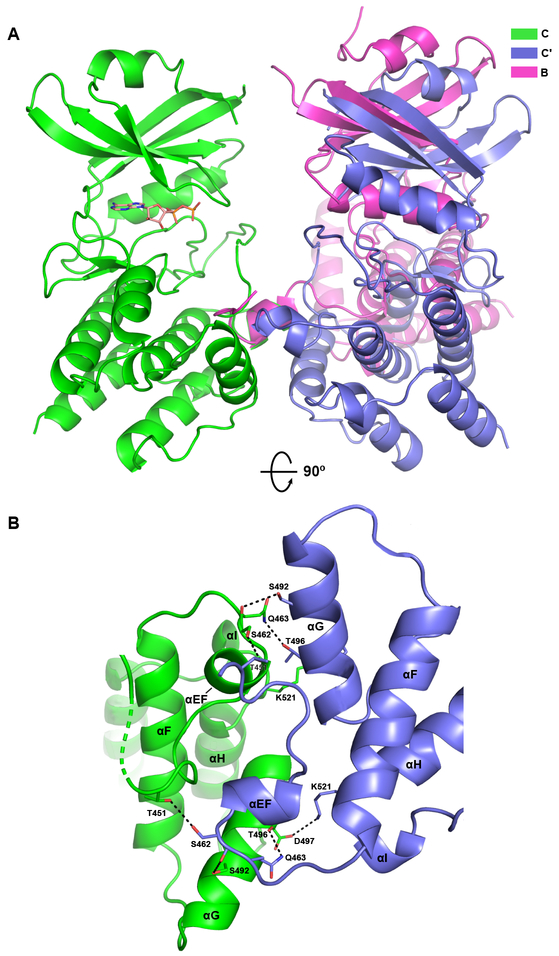

Other Interfaces

The AMPPNP complex forms a second FTF interface between symmetry-related C protomers that does not involve exchanged activation segments. Like the FTF interface with exchange, this interaction is mediated by the C-lobes but the dimer geometry is significantly different (Fig. 4A). Aligning the A and C subunits within the exchanged and nonexchanged dimers, respectively, reveals that the complementary protomers differ by a 38° rotation. The resulting interface is formed by helix αEF from one protomer docking into the cleft formed between the αEF and αG helices on the reciprocal protomer (Fig. 4B). D497 near the end of αG forms a salt bridge with K521 from the loop connecting αH and αI. T496 from helix αG hydrogen bonds to Q463 following αEF. The side chain of S462 hydrogen bonds to T451 in the P+1 loop and the corresponding carbonyl oxygen interacts with S492 in αG. Nonpolar residues contributing most significantly to the interface include I460 which is buried between αEF helices and L452 in the P+1 loop. The mechanistic significance of this interface is unclear. Trans autophosphorylation at T466 is not feasible in this geometry and the docking site on helix αG for the substrate eIF2α is blocked. However, similar interfaces utilizing the αEF and αG helices have been reported for trans-autophosphorylation complexes of PAK159 and PknB60.

Figure 4. Structure of the PKR kinase face-to-face dimer without exchange.

Two symmetry-related C chains of the AMPPNP complex of PKR kinase forming a FTF dimer without exchange of activation segments are depicted using the color scheme from Figure 1. The chains are referred to as C and Cʹ. A) Comparison of the FTF interfaces. The A:B dimer with exchange and the C:Cʹ dimer without exchange were aligned on the A and C protomers on the left, treating the dimers as rigid units. Relative to the Cʹ protomer, the B protomer is rotated by 38°. The bound nucleotide in chain C is depicted in stick representation. B) Detailed view of the interactions stabilizing the interface. The orientation corresponds to a 90° rotation of the structure depicted in part A. Key side chain and main chain atoms are rendered as sticks. Hydrogen bond and salt-bridge interactions are denoted by dashed lines.

The AMPPNP complex forms two BTB interfaces between chains B and C and between chains A and Aʹ (Fig. 1B). These interfaces closely resemble the previously PKR kinase BTB interfaces. Figure S3 shows the B:C BTB dimer and Figure S4 shows an overlay with the corresponding dimer of the phosphorylated kinase (2A19). With the B chains superimposed, the complementary domains are related by a slight rotation of 11°. The interface geometries of the two unphosphorylated BTB dimers are virtually identical (rotation of less than 1°) (Fig S4B). Many of the polar interactions stabilizing the BTB dimer are shared by the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms. Interestingly, additional salt bridges between H322 and D316 in the loop between αC and β4 are only formed in the unphosphorylated dimers. The differences in the overall geometry and intersubunit interactions in two kinds of BTB dimers may relate to loss of the electrostatic interactions of phospho-T446 in the unphosphorylated PKR kinase.

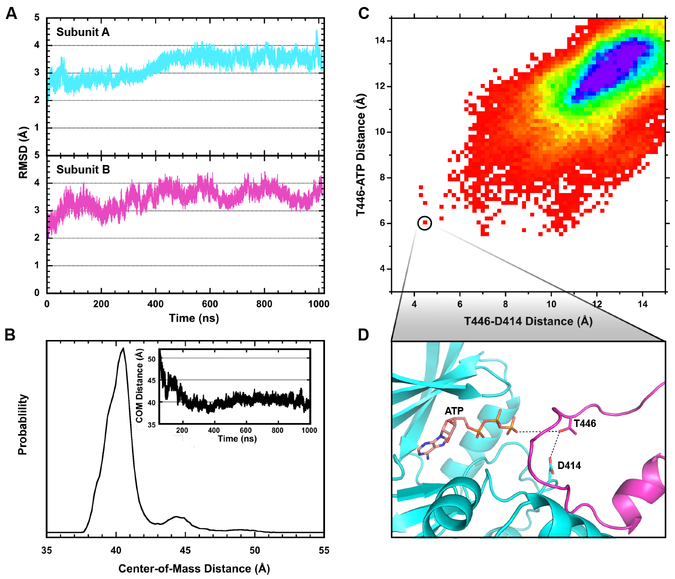

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of the FTF interface with Exchange

All-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were employed to probe the stability and mechanistic significance of the FTF dimer with exchanged activation segments. A FTF model was built based on the A:B dimer which includes the β4-β5 loop and activation segment residues that are unresolved in the crystal structure, ATP, and Mg2+. As expected, the β4-β5 loop and activation segment are highly dynamic during the 1 μs MD trajectory. The remainder of both protomers are relatively rigid, maintaining a root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) of 3–4 Å relative to the starting structure (Fig. 5A). As indicated by analysis of the center-of-mass distances between monomers, the dimer remains associated over the MD trajectory (Fig 5B, inset). Similarly, the buried surface area of the FTF exchanged dimer does not change significantly during the simulation (Fig. S5). For comparison with the established BTB interface18, we also simulated a BTB dimer based on the B and C subunits of the AMPPNP complex. The RMSD of the B subunit is slightly less than the C subunit (Fig. S6) and display a similar degree of structural stability as the FTF protomers. Like the FTF dimer, the center-of-mass distances between monomers in the BTB dimer does not change significantly over the course of the MD simulation. In summary, the MD simulations demonstrate that the crystallographically-observed FTF interface is stable on the μs timescale, supporting its relevance in solution.

Figure 5. Molecular dynamics analysis of the face-to-face dimer with exchange of activation loops.

A) RMSD over the course of the 1 μs simulation relative to the initial structure for subunit A (top) and subunit B (bottom). The highly dynamic β4-β5 loop and activation segment were excluded. B) Distribution of the center-of-mass distances between monomers for the FTF dimer with exchange. The inset shows the trajectory of the distances over the simulation. C) Two-dimensional histogram of the intermonomer T446-ATP and T446-D414 distances. The data correspond to the protomer A Oγ (T446)-protomer B Oγ (ATP) and protomer A Oγ (T446)-protomer B Oδ (D414) distances. The closest distances were recorded for the groups of Oγ (ATP) and the Oδ (D414) atoms. The rainbow color scale for the 1 Å ×1 Å pixels corresponds to occupancies from 1 (red) to 200 (purple). D) Structure of the active site of protomer A corresponding to the pixel circled in part C. The intermonomer T446-ATP and T446-D414 distances are 5.96 Å and 4.45 Å, respectively. The Oγ (T446)-Pγ (ATP)-Pβ (ATP) pseudo-angle is 143.5°.

In the FTF dimer the activation segments are inserted into the complementary protomer, but it is not clear whether the geometry is consistent with catalysis via trans-autophosphorylation since the T446 phosphorylation sites are not resolved (Fig. 3). Phosphoryl transfer in protein kinases likely occurs via in-line nucleophilic attack of the substrate hydroxyl on the γ-phosphate of ATP, with the catalytic aspartate functioning to orient and/or deprotonate the substrate61–63. We examined whether the FTF dimer can access conformations consistent with trans-autophosphorylation where T446 simultaneously interacts with the carboxylate of the catalytic aspartate D414 and the γ-phosphate of ATP. As depicted in a two-dimensional distance histogram, the dimer predominantly populates states inconsistent with transautophosphorylation (Fig. 5C), but the activation segment can transiently adopt conformations where T446 Oγ is near hydrogen bonding distance to Oδ of D414 and within 6 Å of the γ-phosphate oxygens. Although the distances are somewhat greater than reported for ternary complexes of protein kinase A with substrate and ATP61, the angle of attack of the substrate oxygen on the ATP γ-phosphate is 144°, comparable to those observed in the experimental structures (140–173°). These results demonstrate that the intermolecular trans-autophosphorylation of T466 is feasible in the FTF dimer. The reproducibility of this observation was examined by running three additional, shorter simulations. Three independent simulations of the FTF dimer were conducted, each of approximately 120 ns in length. In the three additional trials a consistent qualitative behavior of the activation loop exchange was observed. Monitoring the same variables presented in Fig 5B, it was observed that the protomer A T446 to protomer B D414 distance reached less than 5 Å in all three simulations, with a minimum distance of 2.7 Å in one trial. The protomer A T446 to the protomer B ATP γ-phosphate also displayed close approaches in the additional simulations, reaching less than 8 Å in all trials, with a minimum approach distance of 4.9 Å.

Discussion

A prevalent mechanism in the regulation of protein kinases is the linkage of dimerization with transition to an active conformation29. In PKR, formation of a BTB dimer is believed to represent a critical step in promoting autophosphorylation. However, this dimer geometry places the two active sites distant from the dimer interface and is incompatible with data demonstrating that this reaction can occur in trans. Here, we have identified a novel, FTF dimer interface involving domain swapping of the activation segments that provides a structural basis for trans-autophosphorylation. This interface is observed in two distinct crystal forms, indicating that it is not a crystal-packing artifact. Mutations that disrupt this interaction inhibit PKR activation. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that the FTF interface is stable and the activation loop can adopt a conformation conducive to trans-phosphorylation of T446. The simulations results are based upon equilibrium simulations, an approach which has been used previously in the study of kinase structure and dynamics64,65. Further avenues to explore with simulations could include free-energy calculations to evaluate the coupling of dimer interfaces to the energetics of activation. Approaches including umbrella sampling66 and constructing Markov state models67 have been used previously to generate free energy surfaces of kinase structural transitions.

Activation segment exchange is a recurring motif in dimeric structures of kinases that undergo autophosphorylation68–70. Like PKR, PknB25,60 and IRE121,71,72 form BTB dimer interfaces and also dimerize in a FTF geometry. However, PKR is the only example where these interfaces coexist in the same crystal. The structure of an inactive (K296R) PKR kinase mutant also revealed BTB and FTF interfaces53. However, this FTF dimer does not involve domain swapping. Interestingly, when this FTF dimer is superimposed on the two FTF dimers observed in the AMPPNP complex, the relative domain orientation is closer to the B:C interface with exchange (rotation of 15°) than the C:Cʹ interface without exchange (rotation of 28°). Potentially, the FTF interfaces without activation segment exchange represent intermediate association states leading to the domain swapped complex. In both crystal forms (Figure 1), the alternating BTB and FTF interfaces create extended chains of kinase domains. Large supramolecular protein assemblies are implicated in signaling via other pattern recognition receptors in the innate immunity pathway73 and the unfolded protein response sensor IRE1 forms a rod-like assembly74. However, trimers or higher-order oligomers of PKR kinase have not been detected.

It is noteworthy that all of the protomers in the unphosphorylated enzyme adopt a conformation with the hallmarks of an active kinase: the DFG motif is oriented in, helix αC is positioned to form the critical E308-K296 salt bridge, and a continuous regulatory spine is assembled. This state, previous described as a “prone to autophosphorylate” conformation, is typically enforced via dimerization or hetero-interaction with other kinases, pseudokinases, or regulatory proteins70. The contribution of helix αC to the BTB interface supports a model where this interaction stabilizes the active conformation of PKR by inducing a reorientation of this critical regulatory element that propagates to the active site17. In NEK7, formation of a BTB dimer disrupts an autoinhibitory conformation of Y9723. This tyrosine is conserved in the eIF2α kinases and may also function to link BTB dimerization with PKR activation. Each of the monomers in our structures engages in both BTB and FTF interactions but there is no evidence that the latter is involved in stabilizing the prone to autophosphorylate conformation. The structure of PKR kinase in the monomeric state is not available but it presumably corresponds to an inactive conformation. In GCN2, the inactive enzyme has a DFG-in, helix αC-out conformation75. Interestingly, it exists as an antiparallel BTB dimer where one subunit is rotated approximately 180°. There is evidence that PKR can also form inactive dimers19. In IRE1, the unphosphorylated kinase domains forms a BTB dimer in an active-like conformation71 whereas the ADP complex exists in a FTF dimer in a DFG-in, helix αC-out, inactive conformation72. Disruption of the active BTB dimer in the structurally-related PknB kinase causes it to shift to a range of inactive conformations76.

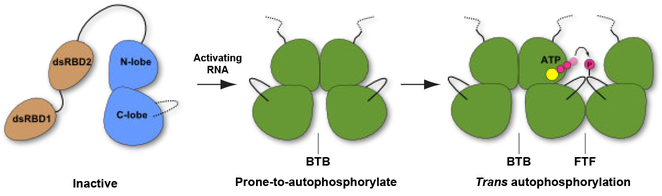

Our results support a multi-step model for PKR activation (Figure 7). In the first step, two or more PKRs bind to an activating RNA via the tandem dsRBDs, bringing the kinase domains into proximity to promote dimerization. Although both BTB and FTF dimers could form upon RNA binding, only the BTB mode induces the prone to autophosphorylate conformation. Potentially, RNAs that induced PKR kinase dimerization yet fail to activate19 may preferentially promote one of the FTF dimers. In the second step, the BTB dimer functions as an enzyme to phosphorylate, in trans, the activation loop of a PKR kinase docked in a domain-swapped, FTF geometry. This substrate may be a monomer, as depicted in Figure 7, or another BTB dimer. In either case, the reaction complex must be only transiently formed since high-order oligomers have not been detected. PKR phosphorylation produces a fully-active kinase and enhances dimerization by ~500-fold16. The newly phosphorylated product can thus serve as a seed to initiate an autocatalytic chain reaction that results in rapid accumulation of activated enzyme. The other members of the eIF2α kinase family may activate via an analogous mechanism. PERK kinase forms a BTB dimer similar to PKR20. Residues implicated in forming an intermolecular salt-bridge that stabilizes the BTB dimer in PKR are conserved in alleIF2α kinases. Disruption of this interaction inhibits PKR as well as PERK and GCN277, suggesting that this interface is critical for activation. Further studies are required to determine whether other members of the eIF2α kinase family undergo trans-autophosphorylation in a domain-swapped FTF configuration.

Figure 7. Multistep model for PKR activation.

The kinase domain of monomeric PKR exists in an inactive conformation. In the first step, PKR binds to activating RNAs via the tandem dsRBDs (dsRBD1 and dsRBD2), bringing two kinase domains into proximity to promote dimerization. Formation of the BTB dimer stabilizes the prone-to autophosphorylate-conformation. In the second step, the BTB dimer phosphorylates the activation loop of a PKR monomer docked in a domain-swapped, FTF geometry. The kinase domain in the inactive conformation is depicted in blue and the prone-to-autophosphorylate and active conformations are shown in green.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Architecture of the unphosphorylated kinase domain.

Figure S2. Comparison of the active sites of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated PKR kinase.

Figure S3: Structure of the PKR kinase back-to-back dimer.

Figure S4. Comparison of BTB interfaces of PKR kinase.

Figure S5. Distribution of the surface area of the FTF dimer interface with exchange.

Figure S6. Molecular dynamics analysis of the back-to-back dimer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the FMX (17-ID-2) beam line of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. We also would like to thank the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light source, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, for the use of beam line 14–1 to collect data. SSRL/SLAC is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02–76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393).

Funding Sources: This work was supported by grant number AI-53615 from the NIH to J.L.C.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors for the structures described in this study have been deposited to the RCSB PDB (www.rcsb.org) with accession numbers 6D3K (AMPPNP complex) and 6D3L (Apo).

References

- (1).Pindel A, and Sadler A (2011) The role of protein kinase R in the interferon response. J Interferon Cytokine Res 31, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nallagatla SR, Toroney R, and Bevilacqua PC (2011) Regulation of innate immunity through RNA structure and the protein kinase PKR. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 21, 119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cole JL (2007) Activation of PKR: an open and shut case? Trends Biochem Sci 32, 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kim Y, Lee JH, Park J-E, Cho J, Yi H, and Kim VN (2014) PKR is activated by cellular dsRNAs during mitosis and acts as a mitotic regulator. Genes Dev 28, 1310–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Nakamura T, Furuhashi M, Li P, Cao H, Tuncman G, Sonenberg N, Gorgun CZ, and Hotmisligil GS (2010) Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase links pathogen sensing with stress and metabolic homeostasis. Cell 140, 338–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Youssef OA, Safran SA, Nakamura T, Nix DA, Hotamisligil GS, and Bass BL (2015) Potential role for snoRNAs in PKR activation during metabolic stress. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 5023–5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ishizuka JJ, Manguso RT, Cheruiyot CK, Bi K, Panda A, Iracheta-Vellve A, Miller BC, Du PP, Yates KB, Dubrot J, Buchumenski I, Comstock DE, Brown FD, Ayer A, Kohnle IC, Pope HW, Zimmer MD, Sen DR, Lane-Reticker SK, Robitschek EJ, Griffin GK, Collins NB, Long AH, Doench JG, Kozono D, Levanon EY, and Haining WN (2019) Loss of ADAR1 in tumours overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature 565, 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Marchal JA, Lopez GJ, Peran M, Comino A, Delgado JR, García-García JA, Conde V, Aranda FM, Rivas C, Esteban M, and García MA (2014) The impact of PKR activation: from neurodegeneration to cancer. FASEB J. 28, 1965–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Liu H, Golji J, Brodeur LK, Chung FS, Chen JT, deBeaumont RS, Bullock CP, Jones MD, Kerr G, Li L, Rakiec DP, Schlabach MR, Sovath S, Growney JD, Pagliarini RA, Ruddy DA, MacIsaac KD, Korn JM, and McDonald ER (2018) Tumor-derived IFN triggers chronic pathway agonism and sensitivity to ADAR loss. Nat. Med 6, 836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Langland JO, Cameron JM, Heck MC, Jancovich JK, and Jacobs BL (2006) Inhibition of PKR by RNA and DNA viruses. Virus Res 119, 100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dzananovic E, McKenna SA, and Patel TR (2018) Viral proteins targeting host protein kinase R to evade an innate immune response: a mini review. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev 34, 33–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Donnelly N, Gorman AM, Gupta S, and Samali A (2013) The eIF2α kinases: their structures and functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 70, 3493–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Pakos Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, and Gorman AM (2016) The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep 17, 1374–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Manche L, Green SR, Schmedt C, and Mathews MB (1992) Interactions between double-stranded RNA regulators and the protein kinase DAI. Mol Cell Biol 12, 5238–5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lemaire PA, Anderson E, Lary J, and Cole JL (2008) Mechanism of PKR Activation by dsRNA. J. Mol. Biol 381, 351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lemaire PA, Lary J, and Cole JL (2005) Mechanism of PKR activation: dimerization and kinase activation in the absence of double-stranded RNA. Journal of Molecular Biology 345, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Dar AC, Dever TE, and Sicheri F (2005) Higher-order substrate recognition of eIF2alpha by the RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. Cell 122, 887–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Dey M, Cao C, Dar AC, Tamura T, Ozato K, Sicheri F, and Dever TE (2005) Mechanistic link between PKR dimerization, autophosphorylation, and eIF2alpha substrate recognition. Cell 122, 901–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Husain B, Hesler S, and Cole JL (2015) Regulation of PKR by RNA: Formation of Active and Inactive Dimers. Biochemistry 54, 6663–6672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Cui W, Li J, Ron D, and Sha B (2011) The structure of the PERK kinase domain suggests the mechanism for its activation. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lee KPK, Dey M, Neculai D, Cao C, Dever TE, and Sicheri F (2008) Structure of the dual enzyme Ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell 132, 89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Huang H, Zeqiraj E, Dong B, Jha BK, Duffy NM, Orlicky S, Thevakumaran N, Talukdar M, Pillon MC, Ceccarelli DF, Wan LCK, Juang Y-C, Mao DYL, Gaughan C, Brinton MA, Perelygin AA, Kourinov I, Guarné A, Silverman RH, and Sicheri F (2014) Dimeric structure of pseudokinase RNase L bound to 2–5A reveals a basis for interferon-induced antiviral activity. Mol. Cell 53, 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Haq T, Richards MW, Burgess SG, Gallego P, Yeoh S, O’Regan L, Reverter D, Roig J, Fry AM, and Bayliss R (2015) Mechanistic basis of Nek7 activation through Nek9 binding and induced dimerization. Nat Commun 6, 8771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ortiz-Lombardía M, Pompeo F, Boitel B, and Alzari PM (2003) Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the PknB serine/threonine kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. 278, 13094–13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Young TA, Delagoutte B, Endrizzi JA, Falick AM, and Alber T (2003) Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis PknB supports a universal activation mechanism for Ser/Thr protein kinases. Nat Struct Biol 10, 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Greenstein AE, Echols N, Lombana TN, King DS, and Alber T (2007) Allosteric activation by dimerization of the PknD receptor Ser/Thr protein kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. 282, 11427–11435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gay LM, Ng HL, and Alber T (2006) A conserved dimer and global conformational changes in the structure of apo-PknE Ser/Thr protein kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Mol. Biol 360, 409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Jura N, Zhang X, Endres NF, Seeliger MA, Schindler T, and Kuriyan J (2011) Catalytic control in the EGF receptor and its connection to general kinase regulatory mechanisms. Mol. Cell 42, 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lavoie H, Li JJ, Thevakumaran N, Therrien M, and Sicheri F (2014) Dimerization-induced allostery in protein kinase regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 39, 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Thomis DC, and Samuel CE (1995) Mechanism of interferon action: characterization of the intermolecular autophosphorylation of PKR, the interferon-inducible, RNA-dependent protein kinase. Journal of Virology 69, 5195–5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).George CX, Thomis DC, McCormack SJ, Svahn CM, and Samuel CE (1996) Characterization of the heparin-mediated activation of PKR, the interferon-inducible RNA-dependent protein kinase. Virology 221, 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ortega LG, McCotter MD, Henry GL, McCormack SJ, Thomis DC, and Samuel CE (1996) Mechanism of interferon action. Biochemical and genetic evidence for the intermolecular association of the RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR from human cells. Virology 215, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kostura M, and Mathews MB (1989) Purification and activation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent eIF-2 kinase DAI. Mol Cell Biol 9, 1576–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).McKenna SA, Lindhout DA, Kim I, Liu CW, Gelev VM, Wagner G, and Puglisi JD (2007) Molecular framework for the activation of RNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem 282, 11474–11486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Dey M, Mann BR, Anshu A, and Mannan MA-U (2014) Activation of protein kinase PKR requires dimerization-induced cis-phosphorylation within the activation loop. J. Biol. Chem 289, 5747–5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Anderson E, Pierre-Louis WS, Wong CJ, Lary JW, and Cole JL (2011) Heparin activates PKR by inducing dimerization. J. Mol. Biol 413, 973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mayo CB, and Cole JL (2017) Interaction of PKR with single-stranded RNA. Sci Rep 7, 3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).van den Berg S, Löfdahl P-Å, Härd T, and Berglund H (2006) Improved solubility of TEV protease by directed evolution. J. Biotechnol 121, 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Potterton L, Agirre J, Ballard C, Cowtan K, Dodson E, Evans PR, Jenkins HT, Keegan R, Krissinel E, Stevenson K, Lebedev A, McNicholas SJ, Nicholls RA, Noble M, Pannu NS, Roth C, Sheldrick G, Skubak P, Turkenburg J, Uski V, Delft, von F, Waterman D, Wilson K, Winn M, and Wojdyr M (2018) CCP4i2: the new graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 68–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, and Wilson KS (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jacobson MP, Pincus DL, Rapp CS, Day TJF, Honig B, Shaw DE, and Friesner RA (2004) A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins 55, 351–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Bowers KJ, Chow E, Xu H, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, Gregersen BA, Klepeis JL, Kolossvary I, Moraes MA, Sacerdoti FD, Salmon JK, Shan Y, and Shaw DE (2006) Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters, in. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Harder E, Damm W, Maple J, Wu C, Reboul M, Xiang JY, Wang L, Lupyan D, Dahlgren MK, Knight JL, Kaus JW, Cerutti DS, Krilov G, Jorgensen WL, Abel R, and Friesner RA (2016) OPLS3: A Force Field Providing Broad Coverage of Drug-like Small Molecules and Proteins. J Chem Theory Comput 12, 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, and Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, and Lindahl E (2008) GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput 4, 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Huang J, Rauscher S, Nawrocki G, Ran T, Feig M, de Groot BL, Grubmüller H, and Mackerell AD (2017) CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nature Publishing Group 14, 71–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bussi G, Donadio D, and Parrinello M (2007) Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys 126, 014101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Parrinello M, and Rahman A (1998) Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. Journal of Applied Physics 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Shrake A, and Rupley JA (1973) Environment and exposure to solvent of protein atoms. Lysozyme and insulin. Journal of Molecular Biology 79, 351–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Li F, Li S, Wang Z, Shen Y, Zhang T, and Yang X (2013) Structure of the kinase domain of human RNA-dependent protein kinase with K296R mutation reveals a face-to-face dimer. Chin. Sci. Bull 58, 998–1002. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Möbitz H (2015) The ABC of protein kinase conformations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854, 1555–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kornev AP, and Taylor SS (2010) Defining the conserved internal architecture of a protein kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 440–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Eyck Yang, J., Ten LF, Xuong N-H, and Taylor SS (2004) Crystal structure of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase mutant at 1.26A: new insights into the catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol 336, 473–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Bastidas AC, Deal MS, Steichen JM, Guo Y, Wu J, and Taylor SS (2013) Phosphoryl transfer by protein kinase A is captured in a crystal lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 4788–4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Taylor CA, Juang Y-C, Earnest S, Sengupta S, Goldsmith EJ, and Cobb MH (2015) Domain-Swapping Switch Point in Ste20 Protein Kinase SPAK. Biochemistry 54, 5063–5071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Wang J, Wu J-W, and Wang Z-X (2011) Structural insights into the autoactivation mechanism of p21-activated protein kinase. Structure 19, 1752–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Mieczkowski C, Iavarone AT, and Alber T (2008) Auto-activation mechanism of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PknB receptor Ser/Thr kinase. EMBO J. 27, 3186–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Das A, Gerlits O, Parks JM, Langan P, Kovalevsky A, and Heller WT (2015) Protein Kinase A Catalytic Subunit Primed for Action: Time-Lapse Crystallography of Michaelis Complex Formation. Structure 23, 2331–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Madhusudan, Akamine P, Xuong N-H, and Taylor SS (2002) Crystal structure of a transition state mimic of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nat Struct Biol 9, 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ho M, Bramson HN, Hansen DE, Knowles JR, and Kaiser ET (1988) Stereochemical course of the phospho group transfer catalyzed by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 110, 2680–2681. [Google Scholar]

- (64).McClendon CL, Kornev AP, Gilson MK, and Taylor SS (2014) Dynamic architecture of a protein kinase. 111, E4623–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Damle NP, and Mohanty D (2014) Mechanism of autophosphorylation of mycobacterial PknB explored by molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 53, 4715–4726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Meng Y, Ahuja LG, Kornev AP, Taylor SS, and Roux B (2018) A Catalytically Disabled Double Mutant of Src Tyrosine Kinase Can Be Stabilized into an Active-Like Conformation. J. Mol. Biol 430, 881–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Shukla D, Meng Y, Roux B, and Pande VS (2014) Activation pathway of Src kinase reveals intermediate states as targets for drug design. Nat Commun 5, 3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Malecka KA, and Peterson JR (2011) Face-to-face, pak-to-pak. Structure 19, 1723–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Xu Q, Malecka KL, Fink L, Jordan EJ, Duffy E, Kolander S, Peterson JR, and Dunbrack RL (2015) Identifying three-dimensional structures of autophosphorylation complexes in crystals of protein kinases. Sci Signal 8, rs13–rs13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Beenstock J, Mooshayef N, and Engelberg D (2016) How Do Protein Kinases Take a Selfie (Autophosphorylate)? Trends Biochem Sci 41, 938–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Joshi A, Newbatt Y, McAndrew PC, Stubbs M, Burke R, Richards MW, Bhatia C, Caldwell JJ, McHardy T, Collins I, and Bayliss R (2015) Molecular mechanisms of human IRE1 activation through dimerization and ligand binding. Oncotarget 6, 13019–13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Ali MMU, Bagratuni T, Davenport EL, Nowak PR, Silva-Santisteban MC, Hardcastle A, McAndrews C, Rowlands MG, Morgan GJ, Aherne W, Collins I, Davies FE, and Pearl LH (2011) Structure of the Ire1 autophosphorylation complex and implications for the unfolded protein response. EMBO J. 30, 894–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Yin Q, Fu T-M, Li J, and Wu H (2015) Structural biology of innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol 33, 393–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Korennykh AV, Egea PF, Korostelev AA, Finer-Moore J, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Stroud RM, and Walter P (2009) The unfolded protein response signals through high-order assembly of Ire1. Nature 457, 687–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Padyana AK, Qiu H, Roll-Mecak A, Hinnebusch AG, and Burley SK (2005) Structural basis for autoinhibition and mutational activation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha protein kinase GCN2. J. Biol. Chem 280, 29289–29299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Lombana TN, Echols N, Good MC, Thomsen ND, Ng H-L, Greenstein AE, Falick AM, King DS, and Alber T (2010) Allosteric activation mechanism of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis receptor Ser/Thr protein kinase, PknB. Structure/Folding and Design 18, 1667–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Dey M, Cao C, Sicheri F, and Dever TE (2007) Conserved intermolecular salt bridge required for activation of protein kinases PKR, GCN2, and PERK. J. Biol. Chem 282, 6653–6660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Krissinel E, and Henrick K (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. Journal of Molecular Biology 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Architecture of the unphosphorylated kinase domain.

Figure S2. Comparison of the active sites of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated PKR kinase.

Figure S3: Structure of the PKR kinase back-to-back dimer.

Figure S4. Comparison of BTB interfaces of PKR kinase.

Figure S5. Distribution of the surface area of the FTF dimer interface with exchange.

Figure S6. Molecular dynamics analysis of the back-to-back dimer.