Abstract

Background

With the establishment of the oncological safety and due to the potential of low anterior resection (LAR) with sphincter salvage in improving the quality of life of patients with low and mid rectal cancers, it has become a popular treatment modality. A potential complication of the procedure is anastomotic dehiscence which results in a significant increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Methods

A literature search for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the role of protective diversion stoma with no stoma in LAR of the rectum was performed in PubMed. The effect size for dichotomous and continuous data was displayed as relative risk (RR) and weighted mean difference (WMD), respectively, with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. A fixed effect or random effects model was used to pool the data according to the result of a statistical heterogeneity test.

Results

Five RCTs were identified and included in the analysis. These yielded 390 patients who had undergone a protective diversion ileostomy at the time of the surgery (LAR) and 378 who had not, resulting in a total of 768 patients, all of whom were included in the meta-analysis. The fashioning of an ileostomy significantly decreased the anastomotic leak (AL) rates (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.21–0.51, p < 0.000) and the reoperation rates (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.15–0.45, p < 0.000).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis found that a protective diversion ileostomy in LAR for rectal cancer decreases the AL rates by one third and the reoperation rates by one fourth. Thus, we conclude that fashioning such a stoma is beneficial.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, Low anterior resection, Diversion stoma, Anastomotic dehiscence, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Identification of the mesorectum as a common site of disease recurrence in rectal cancer led to the concept of total mesorectal excision which reduced the frequency of local recurrence significantly [2, 3]. Advancements in surgical techniques, such as the advent of stapling devices and neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, further led to a higher number of sphincter-preserving resections in low rectal cancers and provided an integrated solution to achieve the treatment goals for rectal cancer, including both local control and the preservation of autonomic visceral pelvic functions. A potential complication of the procedure is anastomotic dehiscence which results in a significant increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality.

This meta-analysis studies the role of fashioning a protective diversion stoma in decreasing the anastomotic leak (AL) rates and the reoperation rates in patients undergoing low anterior resection (LAR) for rectal cancer.

Methods

A literature search was performed in PubMed using the keywords ((stoma [Title/Abstract] OR ileostomy [Title/Abstract]) OR colostomy [Title/Abstract] AND “Rectal Neoplasms” [Mesh]). The criteria for the inclusion of a study in the meta-analysis were as follows: randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing LAR with or without protective diversion stoma in rectal cancer, with data on AL rates and reoperation rates, as well as study available in English and published prior to October 31, 2016. An effort was also made to look for the relevant articles in the referenced publications. Two authors (P.K.G. and A.G.) individually reviewed all papers. In case of ambiguity, a consensus decision was taken by all five co-authors.

Review manager (Cochrane Collaboration's software) version RevMan 5.2 was used for analysis. The effect size for dichotomous and continuous data was displayed as relative risk (RR) and weighted mean difference (WMD), respectively, with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. A fixed effect or random effects model was used to pool the data according to the result of a statistical heterogeneity test. Cochran Q statistic and the I2 test, with p < 0.05 indicating significant heterogeneity, were used to evaluate the heterogeneity among the studies.

Results

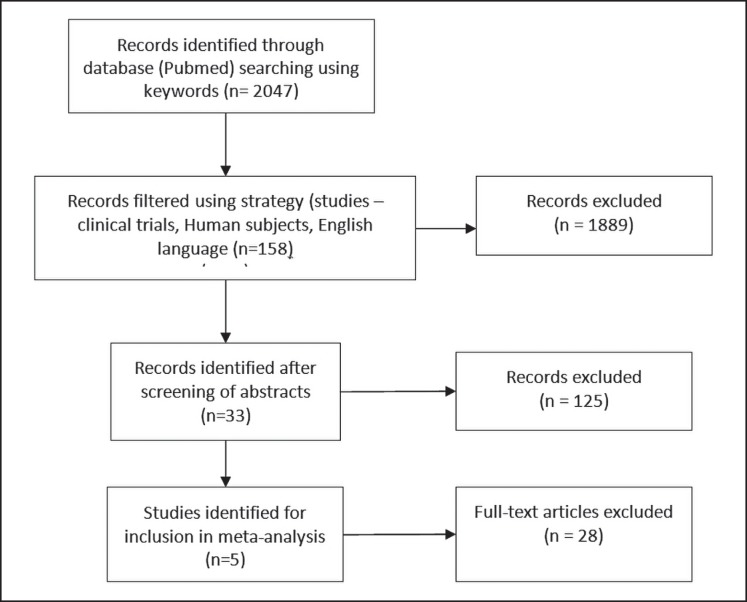

The search strategy yielded 2,047 articles published prior to October 31, 2016. After the relevant filters (language: English, subjects: human, study type: clinical trial) were applied, the search results were confined to 158 publications. Another 125 articles were excluded after careful screening of all abstracts. Five RCTs [4, 5, 6, 7, 8] were identified for inclusion in the meta-analysis after a detailed evaluation of the 33 articles left (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

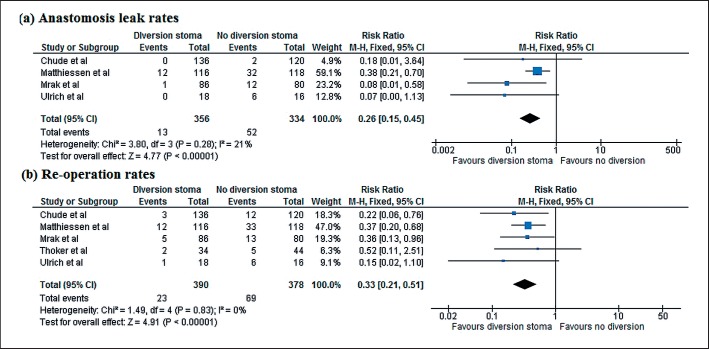

A total of 768 patients were included in the meta-analysis, 390 of whom underwent protective diversion stoma at the time of LAR in rectal cancer, while 378 patients did not. The fashioning of stoma significantly decreased the anastomosis leak rates (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.21–0.51, p < 0.000) and the reoperation rates (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.15–0.45, p < 0.000) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot comparing randomized controlled trials for the outcomes. a AL. b Reoperation rates.

Discussion

AL is one of the most consequential complications after LAR. The rate of colorectal ALs has been variously recorded to range between 0 and 20% in several studies depending on the anatomic location of the anastomosis and other risk factors [9]. One of the reasons for this varied frequency of AL among different studies is a lack of uniform definition of AL. According to the new definition of AL proposed by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer (ISREC), AL is a defect in the intestinal wall integrity at the colorectal or coloanal anastomotic site (including suture and staple lines of neorectal reservoirs), which leads to communication between the intra- and extraluminal compartments [10]. The severity of the leak has been divided into various grades with grade A being defined as a leak requiring no active intervention, grade B as requiring active therapeutic intervention but not a relaparotomy, and grade C as requiring a relaparotomy. Factors which have been found to predispose to AL are male sex, associated comorbid conditions, smoking and alcohol intake history, previous abdominal surgery, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, longer operative time, low location of the tumor, poor intraoperative techniques, loss of blood, etc. [10, 11]. Patients may fall into any of the ISREC grades (A, B, or C) based on their presentation with peritonitis, appearance of pus or feces from the pelvic drain, signs of sepsis, pelvic abscess, rectovaginal fistulae, or even based on routine CT scan in an asymptomatic patient. The occurrence of AL leads to increased morbidity for the patient in the form of increased risk of permanent stoma creation, repeated percutaneous drainage procedures, reoperations, irregular bowel function, fecal incontinence, and a several fold increase in mortality [12]. Almost all patients (> 90%) with AL following LAR may need some therapeutic intervention either image guided or relaparotomy [13].

It is reasonable to question the concerns of those colorectal surgeons who avoid creating a defunctioning stoma for patients who undergo LAR, when the risk of AL is so great and the repercussions so grave. However, there are several disadvantages of a defunctioning stoma which necessitate the generation of level I evidence before changing the surgical strategy to make one. There are several potential disadvantages of diverting stoma such as the need for a second surgery, longer hospital stay, stoma-related complications such as prolapse, retraction, skin excoriation, etc. Moreover, the patient's quality of life significantly deteriorates because of the stoma. In the setting of a high patient load and low resource availability, the costs incurred and the waiting time for stoma closure can act as a deterrent. Furthermore, many of these protective stomas cannot be reversed despite being designed as temporary.

Both an AL and a stoma give rise to morbidity which reduces the patient's quality of life. Further, the risk of AL does not disappear in the presence of a protective stoma; however, diverting stoma decreases the urgent need for reoperation in the presence of AL [14]. It has not been clearly proven that the benefits of a stoma outweigh the morbidity that it inflicts to the patient. This meta-analysis was conducted to find out if foregoing a defunctioning stoma is justified.

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that the AL rates are decreased by one third and reoperation rates by one fourth by fashioning a protective diverting stoma. A summary of the statistics of the RCTs included in the meta-analysis are as shown in Table 1. The analysis pertaining to the leak rates was done using data from all five studies listed above. Reoperation rates were analyzed only in four RCTs, as the study conducted by Thoker et al. [6] did not perform an analysis of the reoperation rates. The forest plot for the analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the statistics compiled from the five RCTs

| Study group | Year of publication | Patients,n |

ALs,n |

Reoperations,n |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | diversion stoma | no diversion stoma | diversion stoma | no diversion stoma | diversion stoma | no diversion stoma | ||

| Matthiessen et al. [4] | 2007 | 234 | 116 | 118 | 12 | 33 | 10 | 30 |

| Chude et al. [8] | 2008 | 256 | 136 | 120 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| Ulrich et al. [5] | 2009 | 34 | 18 | 16 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Thoker et al. [6] | 2014 | 78 | 34 | 44 | 2 | 5 | NA | NA |

| Mrak et al. [7] | 2015 | 166 | 86 | 80 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 12 |

AL, anastomotic leak; NA, not available.

Matthiessenet et al. [4] selected 234 patients out of a total of 821 patients who underwent anterior resection during the study period according to preoperative inclusion criteria. The, the patients were intraoperatively randomized to either receive or not receive a defunctioning stoma based on preset criteria regarding the integrity of the anastomosis and the surgeon's judgement of the major intraoperative adverse events. The clinical definition for AL was used and leaks from the staple lines, rectovaginal fistulas, and pelvic abscesses were included. Asymptomatic radiological leaks were not included. There was no predefined preoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy regime that the patients underwent uniformly. The investigators found that the leak rates and reoperation rates amongst the nonstoma group were significantly higher than in the stoma group. The type of anastomosis performed was not predefined with patients undergoing J-pouch, end-to-end, and side-to-end anastomosis. No difference amongst the leak rates was found between the different anastomosis.

In 2009, Ulrich et al. [5] designed a pilot study with the aim to gather 40 patients and a provision to end the trial early in case major adverse events like the number of reoperations in a single group exceeded that of the other group by five. The trial enrolled 34 patients who were randomized intraoperatively after testing for the completeness of the anastomosis. All patients received a transverse coloplasty pouch and a pouch-anal anastomosis. The trial was stopped early with one leak and no reoperations in the stoma group versus all six leaks requiring operative treatment in the nonstoma group.

In the study conducted by Thoker et al. [6], out of the 78 patients enrolled, 34 patients underwent LAR with defunctioning ileostomy and 44 patients underwent LAR without ileostomy. The leak rates were 6% in the stoma group and 11% in the nonstoma group. They also found that skin excoriation was the most common adverse effect of stoma and hypokalemia was the most common electrolyte imbalance.

Mrak et al. [7] also found significantly higher leak rates in the nonstoma group as compared to the stoma group, and the study had to be terminated after the third interim intention-to-treat analysis. The planned sample size was 222 patients with 111 patients in each group. Only a total of 166 patients were enrolled and randomized preoperatively according to prefixed criteria. Not all patients were treated according to the randomization; 13 patients randomized to the stoma group changed their decision after randomization, and 21 patients from the nonstoma group were defunctioned according to the surgeon's intraoperative judgment. A second as-treated analysis was also carried out which yielded the same results as the intention-to-treat analysis. All patients received a J-pouch and pouch anal anastomosis. Further analysis revealed that a defunctioning stoma and female gender were protective against AL.

A low threshold for fashioning of a protective stoma in patients undergoing LAR as a part of the surgical treatment for rectal cancer can definitely be recommended based on the present meta-analysis of available RCTs. There are certain limitations to the analysis carried out. The number of RCTs included is small. Further the effect of the “surgeon's judgment” upon the randomization in these studies has not been quantified. The effects of preoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and comorbidities and patients factors on AL have not been studied. Further the effect of the anastomosis techniques and the approach for surgery (open vs. laparoscopic) have not been studied.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, we found that a protective diversion ileostomy in LAR for rectal cancer decreases the AL rates by one third and the reoperation rates by one fourth. Thus, we conclude that fashioning such a stoma is beneficial.

Disclosure Statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any funding.

Acknowledgement

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, data analysis, and the drafting, revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014 Apr;383((9927)):1490–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986 Jun;1((8496)):1479–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leong AF. Total mesorectal excision (TME)—twenty years on. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003 Mar;32((2)):159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Simert G, Sjödahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007 Aug;246((2)):207–14. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180603024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulrich AB, Seiler C, Rahbari N, Weitz J, Büchler MW. Diverting stoma after low anterior resection: more arguments in favor. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Mar;52((3)):412–8. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318197e1b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thoker M, Wani I, Parray FQ, Khan N, Mir SA, Thoker P. Role of diversion ileostomy in low rectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2014;12((9)):945–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mrak K, Uranitsch S, Pedross F, Heuberger A, Klingler A, Jagoditsch M, et al. Diverting ileostomy versus no diversion after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Surgery. 2016 Apr;159((4)):1129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chude GG, Rayate NV, Patris V, Koshariya M, Jagad R, Kawamoto J, et al. Defunctioning loop ileostomy with low anterior resection for distal rectal cancer: should we make an ileostomy as a routine procedure? A prospective randomized study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008 Sep-Oct;55((86-87)):1562–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sciuto A, Merola G, De Palma GD, Sodo M, Pirozzi F, Bracale UM, et al. Predictive factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun;24((21)):2247–60. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i21.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, et al. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010 Mar;147((3)):339–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Andersson M, Rutegård J, Sjödahl R. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Colorectal Dis. 2004 Nov;6((6)):462–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Hanna MH, Alizadeh RF, Carmichael JC, Mills S, Pigazzi A, et al. Contemporary management of anastomotic leak after colon surgery: assessing the need for reoperation. Am J Surg. 2016 Jun;211((6)):1005–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan AA, Wheeler JM, Cunningham C, George B, Kettlewell M, Mortensen NJ. The management and outcome of anastomotic leaks in colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2008 Jul;10((6)):587–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna MH, Vinci A, Pigazzi A. Diverting ileostomy in colorectal surgery: when is it necessary? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015 Feb;400((2)):145–52. doi: 10.1007/s00423-015-1275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]