Abstract

Substantial evidence supports the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia. Meanwhile, progressive neurodegenerative processes have also been reported, leading to the hypothesis that neurodegeneration is a characteristic component in the neuropathology of schizophrenia. However, a major challenge for the neurodegenerative hypothesis is that antipsychotic drugs used by patients have profound impact on brain structures. To clarify this potential confounding factor, we measured the cortical thickness across the whole brain using high-resolution T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in 145 first-episode and treatment-naïve patients with schizophrenia and 147 healthy controls. The results showed that, in the patient group, the frontal, temporal, parietal, and cingulate gyri displayed a significant age-related reduction of cortical thickness. In the control group, age-related cortical thickness reduction was mostly located in the frontal, temporal, and cingulate gyri, albeit to a lesser extent. Importantly, relative to healthy controls, patients exhibited a significantly smaller age-related cortical thickness in the anterior cingulate, inferior temporal, and insular gyri in the right hemisphere. These results provide evidence supporting the existence of neurodegenerative processes in schizophrenia and suggest that these processes already occur in the early stage of the illness.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Cortical thickness, Age-related

Introduction

The neuropathology of schizophrenia has been investigated for over a century [1]. In the past two decades, the neurodevelopmental hypothesis, being dominant and popular in this field, has provided significant insight into understanding the etiology and pathology of the illness. With substantial supporting data, this hypothesis suggests that etiological and pathogenic factors disrupt the circuits in the brain during early development, and this results in malfunction during late adolescence or early adulthood [2–4]. Meanwhile, evidence of neurodegeneration in schizophrenia has also been reported [5–7]. Studies have revealed progressive gray matter decreases in first-episode [8–13] and chronic [14–18] patients with schizophrenia. In addition, it has been shown that the rate of cortical thickness decay in patients with schizophrenia is considerably faster than that in healthy controls [19–21]. These results have collectively led to a neurodegenerative hypothesis of schizophrenia, suggesting that neurodegeneration might also be a characteristic component in its neuropathology. This hypothesis can help explain the heterogeneous but commonly deteriorating clinical course of the illness and the apparent ability of treatment to modify its course [22–24], and thus can be complementary to the neurodevelopment hypothesis.

Although a neurodegenerative process is potentially important in understanding the neural mechanisms of schizophrenia, it has been argued that it could be a manifestation of the effects of antipsychotic drug treatment rather than being characteristics of the illness itself [25]. This notion was supported by the fact that most of the aforementioned studies were conducted on individuals who were already on antipsychotic medications, and it has been repeatedly shown that antipsychotic drugs have a profound impact on brain structures and functions [26], both chronically [27, 28] and acutely [29]. Indeed, studies have reported that the progressive cortical decay process is attributable to treatment with antipsychotics [8, 19, 30]. This concept has been further corroborated by even stronger effects reported in animal studies [31]. Furthermore, the neurodegenerative hypothesis is complicated by inconsistent results in the literature [32–34]. For instance, van Haren and colleagues showed that the cortical thickness in patients with schizophrenia progressively decreases across the entire course of the illness relative to healthy controls [19], whereas several other studies have reported no significant age-related changes in either global or regional cortical thickness [33–35].

The confounding effects of antipsychotic drugs on brain structures make it difficult to rigorously test the neurodegenerative hypothesis. To address this issue, in the present study we examined changes in age-related cortical thickness as a function of age in a large sample of first-episode, treatment-naïve patients with schizophrenia. The patient population was not confounded by any antipsychotics or other factors such as times of hospitalization and relapses, and thus could be used to disambiguate the origin of the faster gray matter loss previously reported in schizophrenics [36]. We conclude that there are age-related brain structural changes in patients with schizophrenia which are independent of antipsychotics.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A total of 145 patients with schizophrenia or schizophreniform psychosis were recruited from the inpatient and outpatient units of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University from July 2005 to May 2012. Each patient was assessed based on the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I Disorders (SCID-P; patient version) and diagnosed accordingly [37]. Patients with schizophreniform psychosis were included in the study only if they were found to meet the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia after being followed up for at least 6 months and at most 12 months. We performed the follow-up by contacting the family members or the patients by telephone. We interviewed them and checked the medical records if possible to confirm the diagnosis. If a patient and his/her family could not be reached, or a participant no longer met the criteria of schizophrenia, he/she was excluded from the study. All patients were experiencing first-episode psychosis and were treatment-naïve at the time of clinical assessment and MRI scan. The age at the first psychotic episode for each patient was determined by the onset of psychotic symptoms (delusion, hallucination, disorganized speech, or disorganized/catatonic behaviors) or negative symptoms (affective flattening, alogia, or avolition) recorded in the patient’s medical history or reported by the patient and/or his/her family members. The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was calculated accordingly. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [38] and the Global Assessment Function (GAF) scale [39] were used to assess the severity of clinical symptoms and social function, respectively.

A total of 147 healthy controls were recruited from the local community by poster advertisement. They were interviewed by experienced psychiatrists using the SCID non-patient version to ensure the absence of any major mental disorder. Individuals who were pregnant or had any history of alcohol or drug abuse, or any severe neurological illness such as brain tumor or epilepsy were excluded. All participants were Han Chinese and right-handed, as assessed using Annett’s Hand Preference Questionnaire [40]. Brain MRI images of all participants were inspected by an experienced neuroradiologist and no gross abnormality was observed in any participant. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University, China, and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was given by all participants after being provided with a complete description of the study. Part of the patient sample has been used in other reported studies [41–43].

MRI Data Acquisition and Processing

All participants were scanned on the same scanner, a Signa 3.0-T scanner (U.S. EXCITE, 8-channel head-coil) at Huaxi MR Research Centre, Department of Radiology in West China Hospital of Sichuan University. High-resolution 3D T1-weighted MRI images were acquired using the 3D spoiled gradient echo sequence with the following acquisition parameters: repeat time (TR) = 8.5 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.93 ms, flip angle = 12°, slice thickness = 1 mm, single-shot, field of view (FOV) = 24 × 24 cm2, matrix = 256 × 256, voxel size = 0.47 × 0.47 × 1 mm3. A total of 156 axial slices covering the whole brain were collected for each participant. All scans were inspected for motion artifacts.

Image processing was conducted using the Freesurfer software package (version 5.1.0, http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) [44, 45]. Briefly, preprocessing steps included removal of non-brain tissue, transformation to the Talairach space, and segmentation of gray/white matter. Subsequently, the cortical surface of each hemisphere was inflated to a spherical surface to locate the pial surface and gray/white matter boundaries. The quality of segmentation and surface reconstruction was visually inspected. Topological defects were corrected manually by following the Freesurfer user guidelines. The images from five participants (4 patients and 1 healthy control) had to be manually corrected. Cortical thickness was calculated by finding the shortest distance between a given point on the estimated pial surface and the gray/white matter boundary and vice versa. These two values were then averaged [46]. This calculation method has been shown to be highly reliable [45]. The thickness of each vertex on the cortical surface was mapped onto a common spherical coordinate system using a spherical transformation. Maps were then smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with a full-width-at-half-maximum of 10 mm.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 test for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continuous variables were used to compare differences between two groups. The mean cortical thickness for each hemisphere was first calculated by averaging the cortical thickness of all vertices across the hemisphere. The general linear model (GLM) was used to examine the main effects of diagnosis (i.e. schizophrenia patients or healthy controls) and age, as well as the age × diagnosis interaction on the mean hemispheric cortical thickness. In addition, the partial correlations between mean hemispheric cortical thickness and the age at illness onset, DUP, GAF scores, and PANSS scores after controlling for age and gender were each examined in the patient group. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Vertex-wise GLM was performed using the mri_glmfit function in Freesurfer. First, for each vertex we evaluated the rate of cortical thickness change as a function of age by separately regressing cortical thickness against age in patients and healthy controls after controlling for gender. Second, the age × diagnosis interaction was calculated for each vertex to examine the difference in the rate of change of cortical thickness in relation to age between the patient and control groups after controlling for gender at this vertex. The P value was corrected at the cluster level using Monte Carlo simulations with 10,000 interactions. Third, clusters exhibiting significant differences in the rate of change of cortical thickness between the two groups were selected as regions of interest (ROIs). The mean cortical thickness of ROIs was calculated using Freesurfer for each participant. Finally, correlations between cortical thickness and DUP, age at disease onset, GAF scores, as well as PANSS scores were separately examined for each vertex after controlling for age and gender in the patient group. Statistical significance of correlations was set at P < 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons using the criteria of false discovery rate (FDR).

Results

Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Profiles

The demographic characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 1. Out of 145 patients, 63 were ≤ 20 years old, 35 were > 20 and ≤ 25, 15 were > 25 and ≤ 30, 25 were > 30 and ≤ 40, and 7 were > 40 and ≤ 45. There was no significant difference in gender, age, and duration of education between the patients with schizophrenia and the healthy controls.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of first-episode treatment-naïve patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls.

| Variables | Patients (n = 145) | Healthy controls (n = 147) | t/χ 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female | 69:76 | 71:76 | 0.015 | 0.907 |

| Age (years) | 24.5 ± 7.9 | 25.9 ± 8.5 | −1.484 | 0.139 |

| Range (years) | 16–49 | 16–49 | ||

| Duration of education (years) | 12.2 ± 3.0 | 12.8 ± 3.2 | −1.484 | 0.139 |

| Range (years) | 5–20 | 5–20 | ||

| Age at onset (years) | 23.6 ± 7.9 | |||

| Range (years) | 12.8–43.9 | |||

| Duration of untreated psychosis (months) | 10.8 ± 19.2 | |||

| Median | [25% quantile, 75% quantile] | 4 [1.7, 13.0] | ||

| Range (months) | 1–145 | |||

| GAF scores | 29.5 ± 10.5 | |||

| PANSS scores | ||||

| Total | 93.1 ± 17.3 | |||

| Positive | 25.2 ± 6.1 | |||

| Negative | 19.9 ± 8.2 | |||

| General psychopathology | 48.1 ± 9.6 |

Mean Hemispheric Cortical Thickness

First, we compared the mean cortical thickness of the left and right hemispheres in patients and healthy controls using the independent t-test. There was no difference in the mean cortical thickness for either the left (t = 1.282, P = 0.201) or the right hemisphere (t = 1.468, P = 0.143) between patients (left hemisphere, 2.54 ± 0.10 mm; right hemisphere, 2.55 ± 0.11 mm) and healthy controls (left hemisphere, 2.53 ± 0.10 mm; right hemisphere, 2.53 ± 0.10 mm).

Second, we tested the effects of age and diagnosis on the mean cortical thickness. There was a significant main effect of age on the mean cortical thickness for both the left (F = 85.380, P < 0.001) and the right (F = 76.172, P < 0.001) hemispheres.

There was a significant main effect of diagnosis (F = 7.550, P = 0.006) and age × diagnosis interaction (F = 6.742, P = 0.010) on the mean cortical thickness of the right hemisphere. That meant that there was difference in the mean cortical thickness of the right hemisphere between patients and healthy controls considering the effect of age. However, there was no significant main effect of diagnosis (F = 1.806, P = 0.180) or age × diagnosis interaction (F = 1.463, P = 0.228) on the mean cortical thickness of the left hemisphere.

In the patient group, there were no significant correlations between mean cortical thickness and age at disease onset, DUP, GAF scores, or PANSS scores after controlling for age and gender for either hemisphere (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between mean hemispheric cortical thickness and age at illness onset, DUP, GAF scores, and PANSS scores in the patient group after controlling for age and gender.

| Mean cortical thickness of left hemisphere | Mean cortical thickness of right hemisphere | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| Age at onset | − 0.134 | 0.125 | − 0.101 | 0.248 |

| DUP | 0.139 | 0.113 | 0.105 | 0.230 |

| GAF scores | 0.008 | 0.928 | 0.017 | 0.849 |

| PANSS scores | ||||

| Total | 0.111 | 0.207 | 0.061 | 0.489 |

| Positive | 0.142 | 0.105 | 0.111 | 0.206 |

| Negative | 0.059 | 0.503 | 0.045 | 0.605 |

| General psychopathology | 0.130 | 0.138 | 0.125 | 0.155 |

Vertex-Wise Analysis of Cortical Thickness

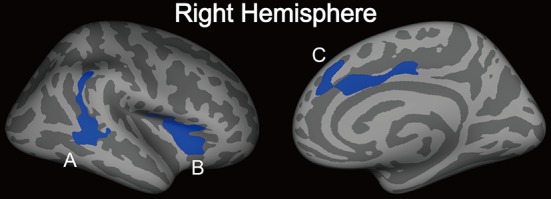

To assess the change of cortical thickness with age in specific brain regions, we regressed cortical thickness against age for individual vertices across the whole brain. There were significant vertex-wise correlations between cortical thickness and age in both patients and healthy controls (Fig. 1). The slope of the regression of cortical thickness against age was predominantly negative across the brain for both groups, suggesting a gradual reduction of cortical thickness with increased age in both healthy participants and patients. In the patient group, regions with significant negative age–cortical thickness slopes were mostly located in the frontal, temporal, parietal, and cingulate gyri. In the control group, regions with significant negative age–cortical thickness slopes were mostly located in the frontal, temporal, and cingulate gyri, albeit to a lesser extent. These results showed that in both patients and healthy controls, the cortical thickness decreased with age, and this trend was considerably more pronounced in patients. However, a cluster located in the temporal gyrus in each hemisphere showed a significant positive cortical thickness–age slope in both patients and healthy controls.

Fig. 1.

Vertex-wise correlation between cortical thickness and age in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Blue regions represent negative correlations and red regions represent positive correlations. Color bars show −log(P). Statistical significance was thresholded at P < 0.05, FDR corrected. SZ, patients with schizophrenia; HC, healthy controls.

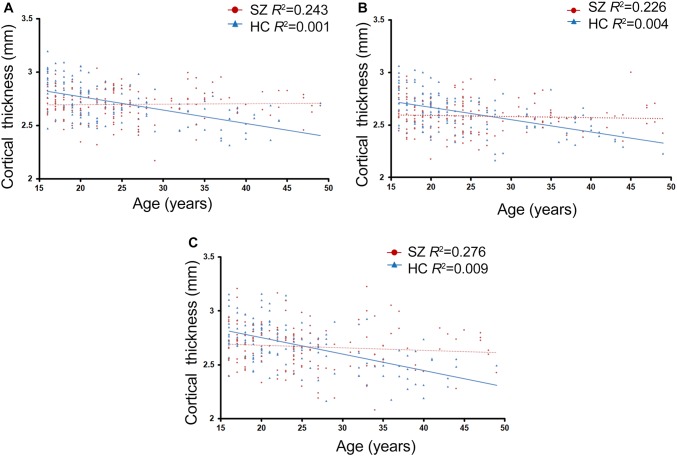

Statistically significant differences were found in the rate of change of cortical thickness with age (i.e. the regression slope of cortical thickness against age) between the patient and control groups (P < 0.05, corrected at the cluster level using Monte Carlo simulations with 10,000 interactions) (Fig. 2). Relative to healthy controls, patients exhibited a significantly smaller age-related cortical thickness in the anterior cingulate, inferior temporal, and insular gyri in the right hemisphere. These three clusters were defined as ROIs. The relationship between mean cortical thickness and age for the three ROIs in patients and healthy controls is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Regions showing significant differences in the rate of change of cortical thickness as a function of age between the patient and control groups. Statistical threshold was set at P < 0.05, corrected at the cluster level using Monte Carlo simulations with 10,000 replications. Significantly faster cortical reduction in patients relative to controls was observed in the temporal and parietal gyrus (A), insula (B), and anterior cingulate gyrus (C). These regions were defined as ROIs.

Fig. 3.

Regression of mean cortical thickness in ROIs (A, temporal and pariental gyrus; B, insula; C, anterior cingulate gyrus) against age in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. SZ, patients with schizophrenia; HC, healthy controls.

No brain region showed a slower reduction in cortical gray matter thickness in patients than healthy controls. No vertex showed a significant difference in the absolute cortical thickness between patients and controls after FDR correction for multiple comparisons. In addition, no correlations between cortical thickness and age at disease onset, DUP, PANSS scores, or GAF scores survived the FDR correction for multiple comparisons after controlling for age and gender in the vertex-wise analysis.

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed the change of cortical thickness with age in un-medicated patients with schizophrenia and matched controls. Our results showed that the cortical thickness decreased with age in most brain regions in both patients and healthy controls, and the rate of age-related gray matter loss was significantly more pronounced in patients with schizophrenia relative to healthy controls, especially in the right anterior cingulate, inferior temporal, and insular gyri. Because the patients recruited in the study were all at their first psychotic episode and treatment-naïve, this difference cannot be attributed to the effects of antipsychotics. Taken together, these results suggest that schizophrenia can be characterized by an age-related loss of gray matter and this loss is already present in the early stage of the illness.

Age-Related Gray Matter Loss Might be a Characteristic Feature in Schizophrenia

Studies have reported faster gray matter loss in both cortical volume [8, 9, 11, 12, 30, 47] and cortical thickness [19, 48–50] throughout the course of the illness. The finding of the present study further suggests that this process is already manifest in the early stage of the disease, and may occur even before the onset of the illness. Particularly, the present study showed that the insular, anterior cingulate, and temporal cortices in patients demonstrated more pronounced cortical thinning relative to healthy controls. Interestingly, these regions coincide with the functional brain network that exhibits significant degeneration in patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia [51]. Moreover, the insular and anterior cingulate cortices have been found to progressively degenerate before the onset of psychosis [52, 53]. All these results collectively suggest that a neurodegenerative process manifested as age-related gray matter loss might be a key feature in schizophrenia.

Faster Age-Related Cortical Thickness Reduction in Schizophrenia Was Not Due to Antipsychotics

The major controversy over the neurodegenerative hypothesis centers on whether faster gray matter loss in patients in fact results from the effects of antipsychotic drugs. Indeed, use of antipsychotics has been shown to have a profound impact on brain structures, making it difficult to conclude whether any structural abnormalities identified are characteristic of the pathophysiology of the disease or merely a confounding effect of treatment [25, 54, 55]. Furthermore, recent research has shown that reductions in cortical thickness are not consistently reported [35]. In addition, different types of antipsychotic may have different effects on the brain. For instance, typical antipsychotics have been associated with brain tissue loss while atypical antipsychotics have not [56]. Furthermore, the clinical functional outcome as a result of treatment has also been related to structural differences in the brain [19, 57, 58]. These factors may all contribute to the inconsistent results in the literature in terms of the rate of gray matter decay between patients and controls [33, 34]. One important contribution of the present study is that it was conducted on treatment-naïve patients and thus eliminated all the confounding factors noted above. As a result, the finding of more pronounced gray matter loss in this patient group provides important evidence supporting the neurodegenerative hypothesis.

Evidence for the “Two-Hit” Model

Given the strong evidence supporting the developmental origin of schizophrenia, early developmental insult may account for the dysfunction of the brain which leads to later neurodegeneration in schizophrenia [59, 60]. Therefore, by considering both the neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative hypotheses, the mechanisms underlying schizophrenia can perhaps be reformulated by progressive developmental models [61, 62], including the “two-hit” model [63, 64]. Specifically, these hypotheses postulate that an early developmental deficit leads to the dysfunction of specific neural networks that account for premorbid signs and symptoms, and the excessive elimination of synapses and loss of plasticity account for the emergence of symptoms. The results of the present study support these models given that the age range of the patients in our study was quite large.

Other Potential Factors that Can Contribute to Faster Cortical Thinning in Schizophrenia

Several factors may contribute to the finding of the present study. One factor is neuronal pruning. The cerebral cortex undergoes progressive thinning from childhood to puberty and early adulthood because of pruning and later becomes steady in normal populations [65]. There is evidence suggesting abnormal pruning in schizophrenia, including reduced synaptic products [66, 67] and reduced spine density and smaller dendritic arbors in the prefrontal cortex [68]. Accelerated neuronal pruning in patients may lead to a faster cortical thinning process in patients. However, since pruning predominantly occurs during the adolescent period, while the age range of the participants in the present study was considerably larger (16–49 years), pruning cannot be the only reason for our finding. Other factors such as neurotoxicity may also cause neuronal shrinkage and thus induce gray matter loss. N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists such as dizocilpine (MK-801) have been found to be neurotoxic, causing cell death, and are used to model schizophrenia [69, 70]. Further studies are needed to determine the exact neurobiological basis underlying the faster cortical thinning process in schizophrenia.

Potential Limitations

It has to be noted that in the present study we used a linear model to test the relationship between cortical thickness and age in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls, although the developmental trajectories of the cortex can be nonlinear [71]. Linear model analysis assumes the same rate of degeneration before and after onset of the first episode. More sophisticated analysis may be needed to elucidate a possibly more complicated pattern in future studies with a bigger sample set.

Another limitation of the present study is that a cross-sectional design was applied. To eliminate the confounding effects of antipsychotic drugs on brain structures, one could theoretically conduct longitudinal studies on un-medicated patients throughout the course of illness to examine possible neurodegenerative processes. However, such studies are not ethical. Alternatively, cross-sectional designs, particularly with large groups of participants, can also offer valuable information on age-related brain changes. In fact, the cross-sectional study design has frequently been used as an important tool for investigating progressive changes in normal brain development and aging [72], as well as in different diseases [73].

Moreover, we carried out a clinical review to confirm the inclusion/exclusion criteria, although urine tests would have provided a more precise measurement of substance abuse. Some participants could not be included due to inability to comprehend the procedures or to their acute clinical status that made interviewing difficult or unreliable. Some factors including stress, anxiety, smoking, and sleep disruption were not recorded and included in our analysis.

Summary

In conclusion, in the present study we found extensive and excessive age-related gray matter loss in the cortex in first-episode and treatment-naïve patients with schizophrenia. These changes were especially pronounced in the right insular, anterior cingulate, and inferior temporal gyri, and cannot be attributed to antipsychotics. This study offers critical insight into understanding the neuropathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Development Program of China (2016YFC0904300), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81630030, 81130024 and 81528008), the National Natural Science Foundation of China/Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Joint Research Scheme (81461168029), and the “135” Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, China (ZY2016103 and ZY2016203).

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Nanyin Zhang, Email: nuz2@psu.edu.

Tao Li, Email: xuntao26@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray RM, Lewis SW. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:681–682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6600.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao X, Tian L, Yan J, Yue W, Yan H, Zhang D. Abnormal rich-club organization associated with compromised cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia and their unaffected parents. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:445–454. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0151-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton WS, McGlashan TH. Antecedents, symptom progression, and long-term outcome of the deficit syndrome in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:351–356. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski SR. Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1183–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyatt RJ. Neuroleptics and the natural course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:325–351. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, van Haren NE, Schnack HG, van der Linden JA, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1002–1010. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLisi LE, Tew W, Xie S, Hoff AL, Sakuma M, Kushner M, et al. A prospective follow-up study of brain morphology and cognition in first-episode schizophrenic patients: preliminary findings. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00376-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLisi LE, Sakuma M, Tew W, Kushner M, Hoff AL, Grimson R. Schizophrenia as a chronic active brain process: a study of progressive brain structural change subsequent to the onset of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1997;74:129–140. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4927(97)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitford TJ, Grieve SM, Farrow TF, Gomes L, Brennan J, Harris AW, et al. Progressive grey matter atrophy over the first 2-3 years of illness in first-episode schizophrenia: a tensor-based morphometry study. Neuroimage. 2006;32:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M. Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their relationship to clinical outcome: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:585–594. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasai K, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, Hirayasu Y, Lee CU, Ciszewski AA, et al. Progressive decrease of left superior temporal gyrus gray matter volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:156–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathalon DH, Sullivan EV, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Progressive brain volume changes and the clinical course of schizophrenia in men: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:148–157. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen LK, Giedd JN, Castellanos FX, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Kumra S, et al. Progressive reduction of temporal lobe structures in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:678–685. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, Gochman P, Blumenthal J, Nicolson R, et al. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11650–11655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201243998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller A, Castellanos FX, Vaituzis AC, Jeffries NO, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Progressive loss of cerebellar volume in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:128–133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sporn AL, Greenstein DK, Gogtay N, Jeffries NO, Lenane M, Gochman P, et al. Progressive brain volume loss during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2181–2189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Haren NE, Schnack HG, Cahn W, van den Heuvel MP, Lepage C, Collins L, et al. Changes in cortical thickness during the course of illness in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:871–880. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie T, Zhang X, Tang X, Zhang H, Yu M, Gong G, et al. Mapping convergent and divergent cortical thinning patterns in patients with deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:211–221. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchy L, Makowski C, Malla A, Joober R, Lepage M. A longitudinal study of cognitive insight and cortical thickness in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiegand LC, Warfield SK, Levitt JJ, Hirayasu Y, Salisbury DF, Heckers S, et al. Prefrontal cortical thickness in first-episode psychosis: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rais M, Cahn W, Schnack HG, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS, van Haren NE. Brain volume reductions in medication-naive patients with schizophrenia in relation to intelligence quotient. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1847–1856. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieberman JA. Is schizophrenia a neurodegenerative disorder? A clinical and neurobiological perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:729–739. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00147-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer-Lindenberg A. Neuroimaging and the question of neurodegeneration in schizophrenia. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:514–516. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snitz BE, MacDonald A, 3rd, Cohen JD, Cho RY, Becker T, Carter CS. Lateral and medial hypofrontality in first-episode schizophrenia: functional activity in a medication-naive state and effects of short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2322–2329. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gur RE, Maany V, Mozley PD, Swanson C, Bilker W, Gur RC. Subcortical MRI volumes in neuroleptic-naive and treated patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1711–1717. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebdrup BH, Skimminge A, Rasmussen H, Aggernaes B, Oranje B, Lublin H, et al. Progressive striatal and hippocampal volume loss in initially antipsychotic-naive, first-episode schizophrenia patients treated with quetiapine: relationship to dose and symptoms. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:69–82. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tost H, Braus DF, Hakimi S, Ruf M, Vollmert C, Hohn F, et al. Acute D2 receptor blockade induces rapid, reversible remodeling in human cortical-striatal circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:920–922. doi: 10.1038/nn.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V. Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:128–137. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis DA. Antipsychotic medications and brain volume: do we have cause for concern? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:126–127. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuperberg GR, Broome MR, McGuire PK, David AS, Eddy M, Ozawa F, et al. Regionally localized thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:878–888. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesvag R, Lawyer G, Varnas K, Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Frigessi A, et al. Regional thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia: effects of diagnosis, age and antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubota M, Miyata J, Yoshida H, Hirao K, Fujiwara H, Kawada R, et al. Age-related cortical thinning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jessen K, Rostrup E, Mandl RCW, Nielsen MO, Bak N, Fagerlund B, et al. Cortical structures and their clinical correlates in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia patients before and after 6 weeks of dopamine D2/3 receptor antagonist treatment. Psychol Med 2018: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Leung M, Cheung C, Yu K, Yip B, Sham P, Li Q, et al. Gray matter in first-episode schizophrenia before and after antipsychotic drug treatment. Anatomical likelihood estimation meta-analyses with sample size weighting. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:199–211. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I & Axis II Disorders (Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1995.

- 38.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Annett M. A classification of hand preference by association analysis. Br J Psychol. 1970;61:303–321. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1970.tb01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Z, Zhang J, Zhang K, Zhang J, Li X, Cheng W, et al. Distinguishable brain networks relate disease susceptibility to symptom expression in schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018 doi: 10.1002/hbm.24190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang S, Li Y, Zhang Z, Kong X, Wang Q, Deng W, et al. Classification of first-episode schizophrenia using multimodal brain features: a combined structural and diffusion imaging study. Schizophr Bull. 2018 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Zhang J, Liu Z, Crow TJ, Zhang K, Li M, et al. “Brain connectivity deviates by sex and hemisphere in the first episode of schizophrenia”-A route to the genetic basis of language and psychosis? Schizophr Bull. 2018 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9:195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bachmann S, Bottmer C, Pantel J, Schroder J, Amann M, Essig M, et al. MRI-morphometric changes in first-episode schizophrenic patients at 14 months follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:301–303. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Deng W, Yao L, Xiao Y, Li F, Liu J, et al. Brain structural abnormalities in a group of never-medicated patients with long-term schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:995–1003. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14091108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godwin D, Alpert KI, Wang L, Mamah D. Regional cortical thinning in young adults with schizophrenia but not psychotic or non-psychotic bipolar I disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6:16. doi: 10.1186/s40345-018-0124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong L, Herold CJ, Zollner F, Salat DH, Lasser MM, Schmid LA, et al. Comparison of grey matter volume and thickness for analysing cortical changes in chronic schizophrenia: a matter of surface area, grey/white matter intensity contrast, and curvature. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seeley WW, Crawford RK, Zhou J, Miller BL, Greicius MD. Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron. 2009;62:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi T, Wood SJ, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Soulsby B, McGorry PD, et al. Insular cortex gray matter changes in individuals at ultra-high-risk of developing psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2009;111:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fornito A, Yung AR, Wood SJ, Phillips LJ, Nelson B, Cotton S, et al. Anatomic abnormalities of the anterior cingulate cortex before psychosis onset: an MRI study of ultra-high-risk individuals. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Haren NE, Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Confounders of excessive brain volume loss in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:2418–2423. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ebdrup BH, Norbak H, Borgwardt S, Glenthoj B. Volumetric changes in the basal ganglia after antipsychotic monotherapy: a systematic review. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:438–447. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Bertens MG, van Haren NE, van der Tweel I, Staal WG, et al. Volume changes in gray matter in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:244–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Haren NE, Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Cahn W, Brans R, Carati I, et al. Progressive brain volume loss in schizophrenia over the course of the illness: evidence of maturational abnormalities in early adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu ML, Zong XF, Mann JJ, Zheng JJ, Liao YH, Li ZC, et al. A review of the functional and anatomical default mode network in schizophrenia. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0090-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lieberman JA. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis and clinical course of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:9–12. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v60n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lieberman JA, Sheitman BB, Kinon BJ. Neurochemical sensitization in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: deficits and dysfunction in neuronal regulation and plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:205–229. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waddington JL, Scully PJ, Youssef HA. Developmental trajectory and disease progression in schizophrenia: the conundrum, and insights from a 12-year prospective study in the Monaghan 101. Schizophr Res. 1997;23:107–118. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woods BT. Is schizophrenia a progressive neurodevelopmental disorder? Toward a unitary pathogenetic mechanism. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1661–1670. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keshavan MS. Development, disease and degeneration in schizophrenia: a unitary pathophysiological model. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:513–521. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(99)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keshavan MS, Hogarty GE. Brain maturational processes and delayed onset in schizophrenia. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:525–543. doi: 10.1017/S0954579499002199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, et al. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature. 2006;440:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis DA, Pierri JN, Volk DW, Melchitzky DS, Woo TU. Altered GABA neurotransmission and prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:616–626. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. The reduced neuropil hypothesis: a circuit based model of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:17–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bubenikova-Valesova V, Horacek J, Vrajova M, Hoschl C. Models of schizophrenia in humans and animals based on inhibition of NMDA receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1014–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beninger RJ, Jhamandas A, Aujla H, Xue L, Dagnone RV, Boegman RJ, et al. Neonatal exposure to the glutamate receptor antagonist MK-801: effects on locomotor activity and pre-pulse inhibition before and after sexual maturity in rats. Neurotox Res. 2002;4:477–488. doi: 10.1080/10298420290031414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaw P, Kabani NJ, Lerch JP, Eckstrand K, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, et al. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3586–3594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5309-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dosenbach NU, Nardos B, Cohen AL, Fair DA, Power JD, Church JA, et al. Prediction of individual brain maturity using fMRI. Science. 2010;329:1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1194144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Castellanos FX, Lee PP, Sharp W, Jeffries NO, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, et al. Developmental trajectories of brain volume abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2002;288:1740–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]