Abstract

Objective

Mechanical thrombectomies with balloon-guide catheters (BGC) are thought to improve successful recanalization rates and to decrease the incidence of distal emboli compared to thrombectomies without BGC. We aimed to assess the effects of BGC on the outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic strokes.

Methods

Studies from PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane library database from January 2010 to February 2018 were reviewed. Random effect model for meta-analysis was used. Analyses such as meta-regression and the “trim-and-fill” method were additionally carried out.

Results

A total of seven articles involving 2223 patients were analyzed. Mechanical thrombectomy with BGC was associated with higher rates of successful recanalization (odds ratio [OR], 1.632; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.293–2.059). BGC did not significantly decrease distal emboli, both before (OR, 0.404; 95% CI, 0.108–1.505) and after correcting for bias (adjusted OR, 1.165; 95% CI, 0.310–4.382). Good outcomes were observed more frequently in the BGC group (OR, 1.886; 95% CI, 1.564–2.273). Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage and mortality did not differ significantly with BGC use.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis demonstrates that BGC enhance recanalization rates. However, BGC use did not decrease distal emboli after mechanical thrombectomies. This should be interpreted with caution due to possible publication bias and heterogeneity. Additional meta-analyses based on individual patient data are needed to clarify the role of BGC in mechanical thrombectomies.

Keywords: Stroke, Thrombectomy, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical thrombectomies are commonly performed for acute ischemic strokes and result in improved angiographic and neurological outcomes compared with intravenous pharmacologic thrombolysis alone [7]. Achieving successful recanalization with a shorter procedure duration is of major interest to neurointerventionists. Accordingly, outcome comparisons focusing on stent types or combination techniques have been performed extensively. However, distal embolization after the procedure has been reported in up to 17% of all cases [20]. In addition, 11.4% of patients with acute middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusions experienced new vascular territory infarctions [10]. Since clot migration distally to the initial occlusion site or to new vascular territories can worsen neurologic outcomes [14], prevention of clot fragmentation and subsequent migration should be investigated alongside rapid and successful recanalization. Balloon-guide catheters (BGC) are increasingly being used for temporary proximal flow arrest during mechanical thrombectomies [4]. In an in vitro MCA hard clot occlusion model, f low arrest using BGC resulted in higher recanalization rates and decreased distal emboli incidence with fewer thrombectomy attempts [5]. Nevertheless, associations between BGC and better angiographic or neurologic outcomes have not been well documented in patients with acute ischemic strokes. Post-hoc analysis of the North American Solitaire Acute Stroke registry [16] showed that complete recanalization, defined as Thrombolysis In Cerebra Ischemia (TICI) 3 grade, was observed more often in the BGC group than in the non-BGC group. In addition, BGC use was independently associated with good clinical outcomes. However, the incidence of distal emboli did not differ significantly between the two groups. Velasco et al. [20] reported that one-pass thrombectomies were achieved more frequently in the BGC group. However, follow-up data about clinical outcome was not provided. Here, we performed an updated meta-analysis including recently published articles to compare the treatment outcomes using BGC versus not using BGC during mechanical thrombectomies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search and selection criteria

Studies from PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials in the Cochrane Library from January 2010 to February 2018 were searched using the MeSH terms or key words [4]. The details of the search strategy are described in Supplementary material. The inclusion criteria were : 1) studies comparing treatment outcomes according to BGC use (BGC vs. non-BGC), 2) studies with participants above 18 years of age, and 3) studies with extractable separate angiographic and clinical outcomes [4]. Exclusion criteria were : 1) studies which did not separate outcomes according to BGC use, 2) studies reporting overlapping data, 3) studies with absence of interest outcomes, 4) studies without extractable data, and 5) review articles or case reports. We also requested additional data pertaining to stroke outcomes by contacting the authors for correspondence. The risk of bias for each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for non-randomized studies (Supplementary Table 1).

Primary outcomes measured were successful recanalization and distal embolization. Secondary outcomes were good outcome at 3 months, mortality, and symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (S-ICH). Successful recanalization was defined as TICI ≥2b [1]. Distal embolization was defined as thrombus fragmentation or embolus migration to a distal branch of the same vascular territory or to a new territory after the procedure [12,17]. Good clinical outcome was defined by a modified Rankin scale score of ≤2. S-ICH was defined as any ICH, subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraventricular hemorrhage concomitant with an increase of ≥4 points on the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) over the baseline score within 24 hours or death [11,16]. Two authors (J.H.A. and S.E.K.) independently evaluated the eligibility of the studies and extracted the data using a uniform, standardized form. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion with the other reviewers (H.C.K. and J.P.J.). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital. The meta-analysis was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Dichotomous variables are shown as odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 test. A random effects model was used due to moderate heterogeneity. Publication bias was determined using Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s regression. Due to the presence of heterogeneity among studies, meta-regression analysis was performed to determine whether onset-to-puncture time (OTP) differences affected the primary outcomes. To resolve publication bias, the “trim and fill” method was additionally conducted to assess the number of missing studies and riskadjusted outcome [13]. A comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) software (CMA v2.2.064; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) was used for all the above, with a statistical significance indicated at p<0.05.

RESULTS

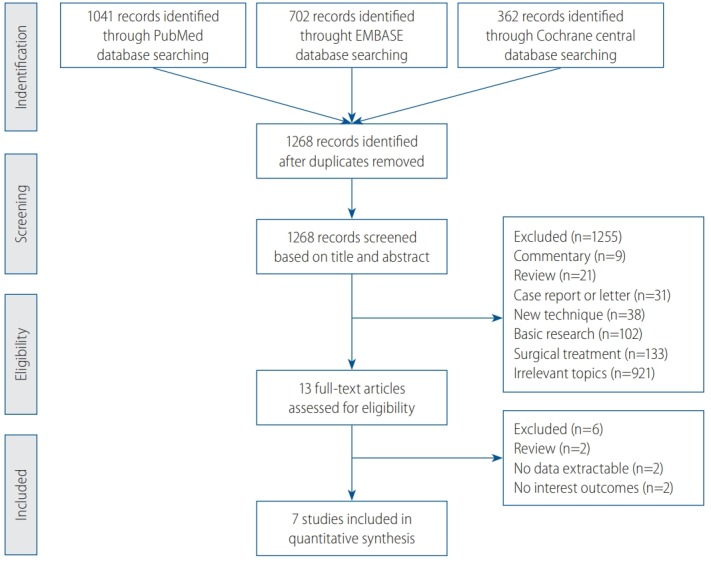

Identification of relevant studies

A flow diagram of the detailed search process for the studies in this meta-analysis is presented in Fig. 1. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we found 13 articles to be eligible. Of them, six articles were excluded in the final analysis due to lack of extractable data (n=2), absence of interest outcomes (n=2), or being review studies (n=2). Finally, seven articles were included in this meta-analysis. The mean age in each study ranged from 63.8 to 70.5 years. The mean NIHSS score at admission was 11.2–17.6 for the BGC group and 13.2–18.3 for the non-BGC group (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram detailing the identification of relevant studies.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data for studies included in this meta-analysis

| Study | Center/design | Procedure type | Total | Age (years) | NIHSS | Prior IV-tPA | OTP (minutes) | PT (minutes) | General anesthesia | Successful recanalization | Distal emboli | No. of passes | Good outcome at 3 months | Mortality | S-ICH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nguyen et al. [16] (2014) | Post-hoc analysis of NASA registry | BGC | 149 | 68.5 | 17.6 | 77 (51.7) | 348 | 120 | 97 (84.4) | 113 (76.0) | 26 (18.2) | 1.8 | 65 (51.6) | 33 (26.2) | 18 (12.2) |

| Non-BGC | 189 | 66.1 | 18.3 | 73 (38.6) | 375 | 161 | 99 (60.0) | 133 (71.0) | 29 (16.0) | 1.9 | 62 (35.8) | 55 (31.8) | 17 (9.0) | ||

| Nguyen et al. [15] (2015) | Post-hoc analysis of TRACK registry | BGC | 279 | 64.8 | NC | NC | 266 | NC | NC | 236 (84.6) | NC | NC | 162 (58.1)* | NC | NC |

| Non-BGC | 255 | 67.6 | NC | NC | 249 | NC | NC | 191 (74.9) | NC | NC | 102 (40.0)* | NC | NC | ||

| Pereira et al. [18] (2015) | Post-hoc analysis of SWIFT-PRIME | BGC | 48 | NC | NC | NC | NC | 60 | NC | NC | NC | 1.6 | 32 (66.7) | 2 (4.2) | NC |

| Non-BGC | 39 | NC | NC | NC | NC | 65 | NC | NC | NC | 1.9 | 21 (53.8) | 4 (10.3) | NC | ||

| Velasco et al. [20] (2016) | Two institutions/ retrospective | BGC | 102 | 70.5 | NC | 43 (42.2) | NC | 25.6 | 102 (100.0) | 96 (94.1) | NC | 1.6 | NC | NC | NC |

| Non-BGC | 81 | 68.8 | NC | 51 (63.0) | NC | 54.8 | 81 (100.0) | 61 (75.3) | NC | 2.4 | NC | NC | NC | ||

| Zaidat et al. [21] (2016) | Post-hoc analysis of STRATIS registry | BGC | 505 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 450 (89.1) | NC | NC | 313 (62.0) | NC | NC |

| Non-BGC | 375 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 327 (87.2) | NC | NC | 184 (49.1) | NC | NC | ||

| Lee et al. [12] (2017) | Single institution/retrospective | BGC | 73 | 66.8 | 11.2 | 31 (42.5) | 202.5 | 99.8 | 0† | 63 (86.3) | 5 (6.8) | 2.6 | NC | 4 (5.5) | 2 (2.7) |

| Non-BGC | 66 | 64.6 | 13.2 | 33 (50.0) | 233 | 124 | 0† | 48 (72.7) | 21 (31.8) | 2.7 | NC | 7 (10.6) | 12 (18.2) | ||

| Oh et al. [17] (2017) | Single institution/retrospective | BGC | 24 | 65.1 | 15.5 | 12 (50.0) | 199 | 78.8 | 0† | 20 (83.3) | 6 (23.1) | 2.4 | 12 (50.0) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) |

| Non-BGC | 38 | 63.8 | 15.8 | 15 (39.5) | 238 | 92.7 | 0† | 25 (65.8) | 20 (57.1) | 3.7 | 6 (15.8) | 6 (15.8) | 4 (10.5) |

Values are presented as number (%).

Number of events among 279 and 255 patients who were followed.

All procedures were done under local anesthesia.

NIHSS : National Institute of Health Stroke Scale, IV-tPA : intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator, OTP : onset to puncture time, PT : procedure time, S-ICH : symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, NASA : the North American Solitaire Acute Stroke, BGC : balloon-guide catheter, TRACK, TREVO stent retriever acute stroke, NC : not commented, SWIFT-PRIME : Solitaire™ With the Intention For Thrombectomy as PRIMary Endovascular Treatment, STRATIS : Systematic Evaluation of Patients Treated With Stroke Devices for Acute Ischemic Stroke

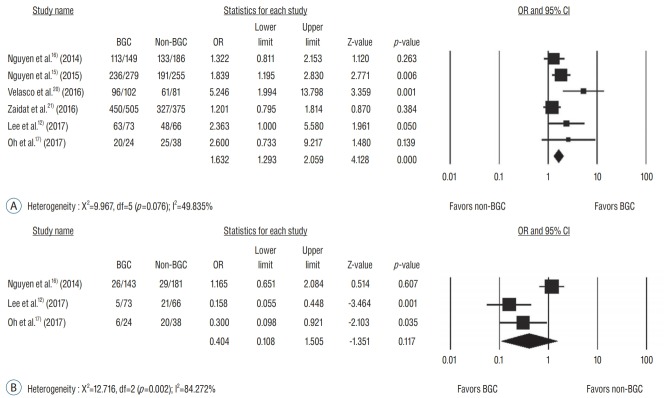

Primary outcomes and publication bias

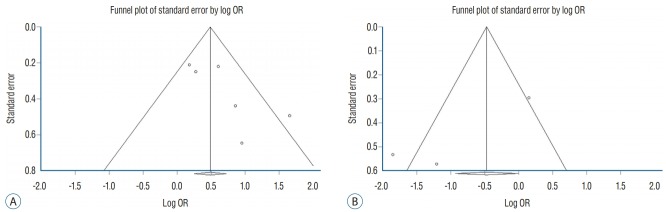

A total of six studies involving 2136 patients were analyzed for successful recanalization. The number of patients with a successful recanalization was 978 (86.4%) in the BGC groups and 785 (78.2%) in the non-BGC groups. Mechanical thrombectomy with BGC increased successful recanalization rates significantly compared to without BGC (OR, 1.632; 95% CI, 1.293–2.059) (Fig. 2A). The number of distal emboli was 37 (15.4%) with BGC and 70 (24.6%) in the non-BGC group, respectively. Mechanical thrombectomy with BGC did not significantly affect the incidence of distal emboli compared to thrombectomy without BGC (OR, 0.404; 95% CI, 0.108–1.505) (Fig. 2B). Publication bias analysis for successful recanalization showed funnel plot asymmetry (Fig. 3A). Egger’s regression test exhibited an intercept of 2.61 (95% CI, -0.53 to 5.77). Regarding distal emboli, funnel plot asymmetry was also observed (Fig. 3B) with intercept of Egger’s regression test of -6.46 (95% CI, -34.48 to 21.55). Accordingly, possible publication bias was observed for each test.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of successful recanalization (A) and distal emboli (B) after mechanical thrombectomy according to BGC use (BGC vs. non-BGC). OR : odds ratio, CI : confidence interval, BGC : balloon-guiding catheter.

Fig. 3.

Publication bias in comparison of successful recanalization (A) and distal emboli (B) after mechanical thrombectomy between the two groups of BGC and non-BGC. OR : odds ratio, BGC : balloon-guiding catheter.

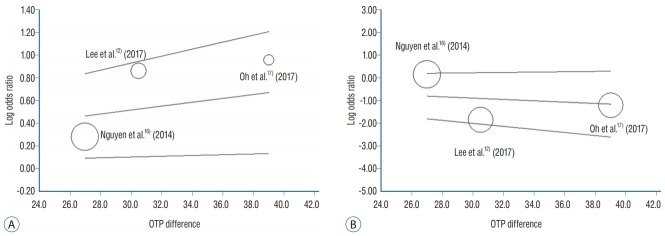

Meta-regression

Meta-regression analysis was conducted to estimate the log ORs of successful recanalization and distal emboli based on differences in the OTP. A regression coefficient of 0.017 (p-value=0.015) was observed in successful recanalization (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, a linear relationship was observed between the OTP differences and the log odds ratios for successful recanalization. Regarding distal emboli, the regression coefficient was -0.030 (p-value=0.118), suggesting absence of significant effect of the OTP differences on the log odds ratio of distal emboli (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Meta-regression of differences in the onset-to-puncture time (OTP) and the log odds ratios for successful recanalization (A) and distal emboli incidence (B) in three studies. The difference in the mean OTP was used in three studies. Each study is represented by a circle, whose size is proportional to the study weight in the meta-analysis. The straight line represents the best line of correlation (p-value=0.015 in A and p-value=0.118 in B).

Trim and fill method

To resolve possible publication bias, we trimmed two studies for successful recanalization. After correction of the forest plot, the adjusted OR was 1.489 (95% CI, 1.191–1.860), suggesting a significant relationship between BGC use and higher rates of successful recanalization (Supplementary Table 2). Regarding distal emboli, we trimmed two studies to resolve publication bias. After correction of the forest plot, the adjusted OR was 1.165 (95% CI, 0.310–4.382), suggesting lack of a significant relationship between BGC use and distal emboli after thrombectomy (Supplementary Table 2).

Secondary outcomes : BGC vs. non-BGC

The number of good outcomes at 3 months was 584 (59.5%) with BGC and 375 (42.6%) in the non-BGC group. Good outcomes were observed more frequently in mechanical thrombectomies with BGC (OR, 1.886; 95% CI, 1.564–2.273). No significant difference in mortality rate was observed according to BGC use (OR, 0.696; 95% CI, 0.441–1.098). The incidence of S-ICH did not differ significantly with BGC use (OR, 0.730; 95% CI, 0.173–3.084) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of secondary outcomes including good outcome at 3 months, mortality and S-ICH

| No. of studies | OR BGC vs. non-BGC | 95% CI | p-value | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good outcome at 3 months | 5 | 1.886 | 1.564–2.273 | <0.001 | 0 |

| Mortality | 3 | 0.696 | 0.441–1.098 | 0.120 | 0 |

| S-ICH | 3 | 0.730 | 0.173–3.084 | 0.669 | 75.896 |

S-ICH : symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, BGC : balloon-guide catheter, OR : odds ratio, CI : confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that BGC enhance successful recanalization. However, BGC use did not decrease distal emboli after mechanical thrombectomies. Nevertheless, possible publication bias and heterogeneity among studies should be considered to the interpretation.

It is believed that mechanical thrombectomy with BGC leads to higher rates of successful recanalization and lower risks of distal emboli by decreasing proximal flow when compared to thrombectomy without BGC. Chueh et al. [5] reported that distal emboli greater than 1 mm in diameter were significantly decreased in the BGC group in an in vitro MCA occlusion model. In addition, aspiration though BGC provided higher flow reversal than with conventional guiding catheter. Conversely, Mokin et al. [14] did not find meaningful differences in successful recanalization with BGC use, although embolization to new vascular territories occurred less frequently in the BGC group than in the non-BGC group in an in vitro MCA clot model. A recent meta-analysis [4] reported a significantly higher rate of successful recanalization in the BGC group (78.9%) than in the non-BGC group (67.0%). Nevertheless, differences in OTP between the two groups, affected treatment outcomes. In this study, we explored the effects of OTP differences on primary outcomes with BGC use. Regarding successful recanalization, the regression coefficient was 0.017, indicating a linear relationship between the OTP difference and the log odds ratio of successful recanalization. Accordingly, OTP difference can be a moderator which may have a substantial effect on outcome prediction. Five studies [15-18,21] compared clinical outcomes at 3 months according to BGC use. The BGC group had more patients with good clinical outcomes than the non-BGC group. Recently, Zaidat et al. [22] reported that the first-pass effect, defined as complete recanalization with a single device pass, was associated with better clinical outcome. In their study, ischemic stroke patients with first-pass effects resulted in better outcomes at 3 months compared to those without first-pass effects. Velasco et al. [20] showed that successful thrombectomies with a single device pass was observed more frequently in the BGC group than in the non-BGC group with markedly shorter durations. Therefore, it is possible that mechanical thrombectomy with BGC leads to improved clinical outcome by enabling first-pass recanalization and significantly decreasing procedure time. However, the effects of anesthesia should also be considered when assessing clinical outcome after the procedure. According to Brinjikji et al. [3], the use of general anesthesia significantly decreased the rates of good clinical outcome after adjusting for baseline NIHSS. Therefore, additional metaanalyses based on individual patient data that considers OTP difference and anesthesia type, are required.

Concerns about BGC use during mechanical thrombectomy include: patients’ tolerance to temporal flow arrest [5], delivery time based on the insertion of the BGC in the proximal internal carotid artery, especially in patients with difficult arches, and groin puncture site complications due to larger 8 Fr or 9 Fr groin sheath that are required for BGC use. To address the first concern, immediate partial MCA flow reversal has been noted in an in vitro MCA occlusion model [5] when using stent retrievers during BGC inflation. However, in clinical circumstances, patients with poor collateral vasculature may have a higher risk of ischemic brain injury during balloon inflation. As to the second concern, a comparison of guiding catheter delivery time based on BGC use has not been well documented. Overall, patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy without BGC appear to be younger than those in the BGC group [4,16]. Consequently, sample selection bias could occur, due to patients with more tortuous arches being more likely to be treated with conventional guiding catheters [4,16]. Finally, a subset of neurointerventionists are reluctant to use BGC due to complications associated with the groin puncture site. Shah et al. [19] reported lower groin site complication rates of 0.4–0.8%; however, safety issue, especially in the elderly patients with atherosclerotic stenosis of the internal iliac arteries or a history of coagulopathy, should be studied further.

This study has a few limitations. First, all the studies included were retrospective with small sample sizes. Consequently, inherent selection biases, such as differences in the intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator [9,16], and anesthesia type (general vs. local anesthesia) may inf luence the results. Second, technical variations in the mechanical thrombectomy process were not considered. Although stent retrievals with BGC are commonly performed, multimodal approaches such as the direct aspiration first-pass technique (ADAPT), stent-retrieving aspiration catheter with proximal balloon (ASAP), continuous aspiration before intracranial vascular embolectomy (CAPTIVE), stent-retriever-assisted vacuum-locked extraction (SAVE) and stent retrieval with simultaneous aspiration of the clot (Solumbra) exists and are used in daily practice [2,6,8]. Advances in endovascular technologies will determine the choice and timing of these interventions. Accordingly, the clinical efficacy of BGC should be evaluated under various conditions through large-scale prospective studies.

CONCLUSION

Our study showed that mechanical thrombectomy with BGC demonstrated a higher rate of successful recanalization compared to thrombectomy without BGC. Regarding distal emboli incidence, BGC use did not decrease the events. Although possible publication bias was observed, the adjust ORs did not reach statistical significance. Nevertheless, the retrospective format and small sample sizes of the analyzed studies limit our conclusion. Meta-analyses based on individual patient data derived from large, prospective and randomized controlled trials are necessary to properly compare the angiographic and neurological outcomes according to BGC use in mechanical thrombectomy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Velasco A (University of Muenster, Germany) and Yoon SM (University of Soonchunhyang, Korea) for providing additional study information.

This research was supported by the Hallym Research Fund (HURF-2017-05), BioGreen21 (PJ01313901) of the Rural Development Administration and the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and Communication Technologies and Future Planning of the Korea Government (No. 2017M3A9E8033223).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

INFORMED CONSENT

This type of study does not require informed consent.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization : JPJ

Data curation : JHA, SEK

Formal analysis : SEK

Funding acquisition : JHA

Methodology : HCK

Project administration : JHA

Visualization : SSC

Writing - original draft : JHA, JPJ

Writing - review & editing : JPJ

Supplementary Materials

The online-only data supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2018.0165.

Quality assessment of studies included in the meta-analysis using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Publication bias analysis using the “trim-and-fill” methods for identification of successful recanalization and distal emboli in this meta-analysis

References

- 1.Almekhlafi MA, Menon BK, Freiheit EA, Demchuk AM, Goyal M. A meta-analysis of observational intra-arterial stroke therapy studies using the merci device, penumbra system, and retrievable stents. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:140–145. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez CM, McCarthy DJ, Sur S, Snelling BM, Starke RM. Comparing mechanical thrombectomy techniques in the treatment of large vessel occlusion for acute ischemic stroke. World Neurosurg. 2017;100:681–682. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinjikji W, Pasternak J, Murad MH, Cloft HJ, Welch TL, Kallmes DF, et al. Anesthesia-related outcomes for endovascular stroke revascularization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48:2784–2791. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinjikji W, Starke RM, Murad MH, Fiorella D, Pereira VM, Goyal M, et al. Impact of balloon guide catheter on technical and clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10:335–339. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chueh JY, Kühn AL, Puri AS, Wilson SD, Wakhloo AK, Gounis MJ. Reduction in distal emboli with proximal flow control during mechanical thrombectomy: a quantitative in vitro study. Stroke. 2013;44:1396–1401. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.670463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto S, Ohshima T, Ishikawa K, Yamamoto T, Shimato S, Nishizawa T, et al. A stent-retrieving into an aspiration catheter with proximal balloon (ASAP) technique: a technique of mechanical thrombectomy. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e468–e475. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387:1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeon JP, Kim SE, Kim CH. Primary suction thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;163:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim CH, Jeon JP, Kim SE, Choi HJ, Cho YJ. Endovascular treatment with intravenous thrombolysis versus endovascular treatment alone for acute anterior circulation stroke : a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2018;61:467–473. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2017.0505.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurre W, Vorlaender K, Aguilar-Pérez M, Schmid E, Bäzner H, Henkes H. Frequency and relevance of anterior cerebral artery embolism caused by mechanical thrombectomy of middle cerebral artery occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1606–1611. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapergue B, Blanc R, Guedin P, Decroix JP, Labreuche J, Preda C, et al. A direct aspiration, first pass technique (ADAPT) versus stent retrievers for acute stroke therapy: an observational comparative study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1860–1865. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DH, Sung JH, Kim SU, Yi HJ, Hong JT, Lee SW. Effective use of balloon guide catheters in reducing incidence of mechanical thrombectomy related distal embolization. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:1671–1677. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SU, Hong EP, Kim BJ, Kim SE, Jeon JP. Delayed cerebral ischemia and vasospasm after spontaneous angiogram-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage: an updated meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018;115:e558–e569. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mokin M, Setlur Nagesh SV, Ionita CN, Mocco J, Siddiqui AH. Stent retriever thrombectomy with the cover accessory device versus proximal protection with a balloon guide catheter: in vitro stroke model comparison. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:413–417. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen TN, Castonguay AC, Nogueira RN, English J, Farid H, Veznedaroglu E, et al. Balloon guide catheter improved clinical outcomes, revascularization and decreased mortality in Trevo thrombectomy. Anaylsis of the TREVO Stent Retreiver Acute Stroke (TRACK) Registry. Florida: Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen TN, Malisch T, Castonguay AC, Gupta R, Sun CH, Martin CO, et al. Balloon guide catheter improves revascularization and clinical outcomes with the solitaire device: analysis of the North American Solitaire Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2014;45:141–145. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh JS, Yoon SM, Shim JJ, Doh JW, Bae HG, Lee KS. Efficacy of balloonguiding catheter for mechanical thrombectomy in patients with anterior circulation ischemic stroke. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2017;60:155–164. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.0809.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira V, Siddiqui A, Jovin T, Yavagal D, Levy E, Bonafé A, et al. P-016 role of balloon guiding catheter in mechanical thrombectomy using stentretrivers subgroup analysis of swift prime. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7(Suppl 1):A30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah VA, Martin CO, Hawkins AM, Holloway WE, Junna S, Akhtar N. Groin complications in endovascular mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a 10-year single center experience. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:568–570. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasco A, Buerke B, Stracke CP, Berkemeyer S, Mosimann PJ, Schwindt W, et al. Comparison of a balloon guide catheter and a non-balloon guide catheter for mechanical thrombectomy. Radiology. 2016;280:169–176. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaidat O, Liebeskind D, Jahan R, Froehler M, Aziz-Sultan M, Klucznik R, et al. O-005 influence of balloon, conventional, or distal catheters on angiographic and technical outcomes in STRATIS. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8(Suppl 1):A3–A4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaidat OO, Castonguay AC, Linfante I, Gupta R, Martin CO, Holloway WE, et al. First pass effect: a new measure for stroke thrombectomy devices. Stroke. 2018;49:660–666. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quality assessment of studies included in the meta-analysis using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Publication bias analysis using the “trim-and-fill” methods for identification of successful recanalization and distal emboli in this meta-analysis