Abstract

Background

Loss-of-function mutations in the CLCN2 gene were recently discovered to be a cause of a type of leukodystrophy named CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy (CC2L), which is characterized by intramyelinic edema. Herein, we report a novel mutation in CLCN2 in an individual with leukodystrophy.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old woman presented with mild hand tremor, scanning speech, nystagmus, cerebellar ataxia in the upper limbs, memory decline, tinnitus, and dizziness. An ophthalmologic examination indicated macular atrophy, pigment epithelium atrophy and choroidal capillary atrophy. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the diffuse white matter involvement of specific white matter tracts. Decreased diffusion anisotropy was detected in various brain regions of the patient. Diffusion tensor tractography (DTT) showed obviously thinner tracts of interest than in the controls, with a decreased fiber number (FN), increased radial diffusivity (RD) and unchanged axial diffusivity (AD). A novel homozygous c.2257C > T (p.Arg753Ter) mutation in exon 20 of the CLCN2 gene was identified.

Conclusion

CC2L is a rare condition characterized by diffuse edema involving specific fiber tracts that pass through the brainstem. The distinct MRI patterns could be a strong indication for CLCN2 gene analysis. The findings of our study may facilitate the understanding of the pathophysiology and clinical symptoms of this disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12883-019-1390-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ClC-2 chloride channels, Leukoencephalopathies, MRI, Diffusion tensor imaging

Background

CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy (CC2L), also known as leukoencephalopathy with ataxia (LKPAT; MIM #615651), is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the CLCN2 gene (600570) on chromosome 3q27.1, causing the dysfunction of its encoded ClC-2 chloride channel protein, which is characterized by intramyelinic edema [1–3]. The molecular background of CC2L remains elusive. Since the identification of CC2L in 2013 by Depienne et al., only 13 cases have been reported in detail. The majority of patients show mild clinical phenotypes with prolonged survival. Herein, we report a novel and pathogenic variant of CLCN2 in a woman with leukodystrophy and visual impairment. For the first time diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) technique was employed to explore the microstructural changes of this disease.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old woman presented with mild intention tremor of her hands that had developed at the age of 22. This symptom had been slowly progressive and had been accompanied with speech impediments characterized by a slow rate of speech and a flat voice since the age of 37. The patient complained of mild memory decline, mild tinnitus in both ears, and occasional dizziness. From a young age, she had experienced poor vision in both eyes, which had gradually worsened. She had a history of hyperthyroidism and had been disease free before the onset of neurologic symptoms. The patient was born of a consanguineous union. The family diagram is presented in Fig. 1c.

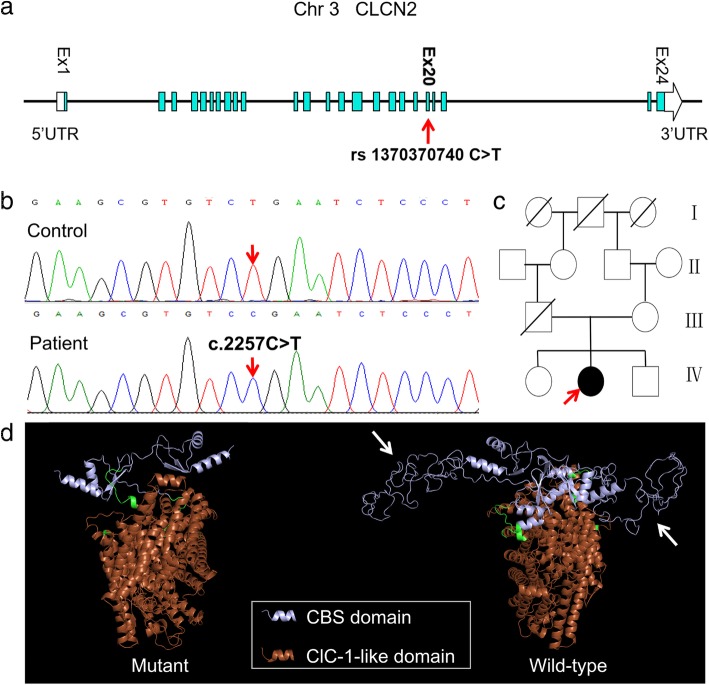

Fig. 1.

Pedigree and molecular findings of the patient. a Schematic representation of CLCN2 on chromosome 3q27.1 showing a novel homozygous nonsense mutation located in exon 20. b Sequencing chromatograms of this mutation. c Pedigree of the patient. Her father died of brain glioma. d Ribbon diagrams of the predicted CLCN2 structure from wild-type and p.Arg753Ter mutant protein. Some structures (arrows) in the cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) domain of the mutant protein are missing

A neurological examination indicated scanning speech, horizontal nystagmus in both eyes, cerebellar ataxia and postural tremor in the upper limbs at a frequency of approximately 8 Hz. Bilateral prolonged latency and a slightly reduced amplitude of the P100 wave in the visual evoked potential and central injury in the brainstem auditory evoked potentials were detected. The visual acuity was 0.15 in the right eye and 0.10 in the left eye, which was not corrected by eyeglasses. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) indicated macular atrophy, especially in the outer segment layer. Fundus fluorescence angiography (FFA) showed strong macular fluorescence changes, indicating pigment epithelium atrophy, and spots inside that were lacking fluorescence, indicating choroidal capillary atrophy. Thyroid-stimulating hormone and parathyroid hormone levels were slightly elevated. Examinations of cognitive function and motor and somatosensory evoked potentials were normal.

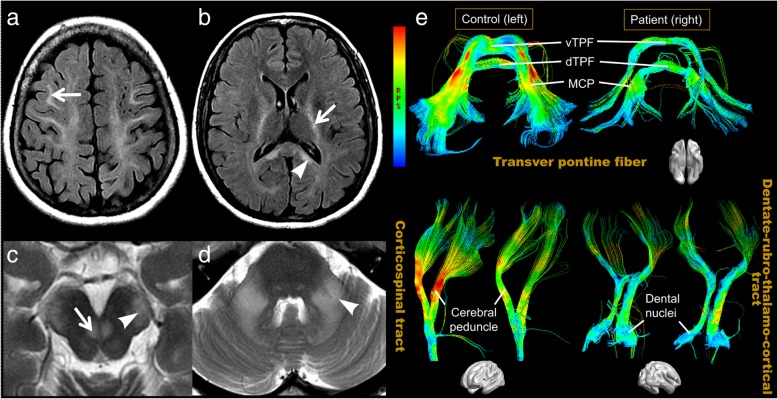

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed confluent white matter abnormalities with hypointense T1-weighted and hyperintense T2-weighted signals, with the symmetrical involvement of the internal capsules, cerebral peduncles, and middle cerebellar peduncles (Fig. 2a-d). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showed hyperintensity in the pathological areas, with no restrictions on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map. No enhanced lesion was found on the post-gadolinium T1-WI sequence. The brain atrophy was unremarkable. Brain DTI images were acquired and compared to those from three gender- and age- (less than 5 years apart) matched healthy controls. Decreased fractional anisotropy (FA) values were found in almost all regions with white matter hyperintensity (WMHI), as well as in specific structures of normal-appearing white and gray matter [see Additional file 1]. A reduced fiber number (FN) was detected in areas with obvious FA reductions, when compared with that in the controls [see Additional file 1]. The findings also revealed decreased axial diffusivity (AD) in the optic nerves, and increased radial diffusivity (RD) in the middle cerebellar peduncles and cerebral peduncles of the patient. On diffusion tensor tractography (DTT), the white matter tracts of interest were visibly thinner than those in the controls, as illustrated in Fig. 2e.

Fig. 2.

Conventional brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor tractographies (DTTs) of the patient. Axial T2-FLAIR (a, b), and T2-weighted (c, d) MRI of the patient demonstrate abnormal hyperintensities in the bilateral frontal (a, arrow) and parietal white matter and the splenium (arrowhead, b) of the corpus callosum, internal capsule (arrow, b), cerebral peduncle (arrowhead, c), DSCP (arrow, c), and middle cerebellar peduncle (arrowhead, d). On DTT (e), the CST, transverse pontine fibers, and dentate nucleus tracts of the patient are obviously thinner and have a “darker color” in the pathological tracts, which indicates lower fractional anisotropy (FA) values, when compared with those in a control. DSCP = decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle, CST = corticospinal tract, vTPF = ventral transverse pontine fiber, dTPF = dorsal transverse pontine fiber, MCP = middle cerebellar peduncle

Whole-exome sequencing revealed a novel homozygous c.2257C > T (p.Arg753Ter) mutation in exon 20 of the CLCN2 gene, which was a nonsense mutation that altered the 753rd Arg in the encoding protein and generated a stop codon (Fig. 1a, b). This change was not reported in any genetic database. Homology modelling suggested the disruption of cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) domain by this variant (Fig. 1d), which was considered to be pathogenic. The patient’s mother was a heterozygous carrier of this mutation.

Discussion and conclusions

ClC-2: a brief overview

ClC-2 is a type of permeable channel for chloride ions that spans the cell membrane [4, 5]. This protein shows widespread tissue expression, including in the brain, pancreas, kidney, liver, hearts, lungs, skeletal muscles and gastrointestinal tract [4–6]. In the central nervous system, ClC-2 mainly localizes to the endfeet of GFAP-positive astrocytes that surround the blood vessels, to the gap junctions along the circumference of oligodendrocytes, and to pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus [1, 3, 7]. Under physiological conditions, ClC-2 plays an important role in transepithelial transport, ion homeostasis, and the regulation of cell excitability [4, 6]. The disruption or abnormality of ClC-2 may affect these organs or tissues, causing various disease conditions, namely, channelopathies [6]. Humans harboring loss-of-function CLCN2 variants and Clcn2 knockedout (KO) mice share overlapping phenotypes, mainly including leukoencephalopathy, male infertility, and visual impairment. However, gain-of-function CLCN2 mutations have been suggested as a cause of a substantial fraction of familial hyperaldosteronism type II [7].

Research on the molecular basis of CC2L

The molecular background of CC2L remains elusive. Functional and biochemical analyses indicated that Clcn2 mutations could cause defective ClC-2 functional expression, probably through a complex mechanism involving reduced cellular and plasma membrane density, increased turnover, and impaired gating of ClC-2 [8, 9]. A reduction in the ClC-2-mediated currents was observed in oligodendrocytes of Clcn2 KO mice and in A500V-ClC-2 expressing mammalian cells [8, 10], supporting the ideas of Depienne et al., who suggested that ClC-2 disruption might result in the disturbance of the compensation of action-potential-induced ion shifts [1], leading to osmotic intramyelinic edema [3]. Recent studies have shown that GlialCAM/MLC1 complex, which physically binds ClC-2 [11, 12], increased the activity of A500V-ClC-2 [8], while the additional disruption of GlialCAM aggravated the vacuolization in Clcn2 KO mice [10]. Together, these findings indicate that functions of the mutant ClC-2 protein are at least partly regulated by the GlialCAM/MLC1 by unknown molecular mechanisms possibly involved in the pathophysiology of CC2L.

Clinical features

The clinical manifestations of the reported patients and the CLCN2 variants that they carried are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Our patient displayed a clinical phenotype similar to the previous cases. However, she also developed asymptomatic hyperthyroidism and hyperparathyroidism with unknown causes, which were not previously seen in those cases. In consideration of the high expression of ClC-2 in the glands [4], the relationship between CLCN2 mutations and the abnormal function of the thyroid and parathyroid should be investigated in future studies.

Table 1.

Clinical features of the reported patients with CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy

| Features | No. of subject |

|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 12 (86) |

| Male | 2 (14) |

| Age at first sign | 3 months - 57 years (27.87 ± 18.82) |

| Presenting signs (%) | |

| Ataxia | 5 (36) |

| Headache | 4 (29) |

| Action tremor | 3 (21) |

| Visual changes | 3 (21) |

| Psycho-cognitive problems | 2 (14) |

| Tinnitus and vertigo | 1 (7) |

| Limbs numbness | 1 (7) |

| Azoospermia | 1 (7) |

| Seizure | 1 (7) |

| Motor dysfunction (%) | 13 (93) |

| Cerebella ataxia | 11 |

| Action tremor | 5 |

| Spasticity | 2 |

| Seizure | 1 |

| Paraparesis | 1 |

| Psycho-cognitive problems (%) | 5 (36) |

| Learning disability | 3 |

| Psychosis | 1 |

| Mild memory decline | 1 |

| Mild executive dysfunction | 1 |

| Headache (%) | 5 (36) |

| Ocular changes (%) | 4 (29) |

| Uncorrectable diminished visual acuity | 3 |

| Optic neuropathy | 3 |

| Retinopathy | 4 |

| Visual field defects | 4 |

| Abnormal evoked potential (%) | 3 (21) |

| Brainstem auditory evoked potential | 2 |

| Visual evoked potential | 2 |

| Motor evoked potential | 1 |

| Auditory abnormality (%) | 3 (21) |

| Hearing loss | 2 |

| Tinnitus | 2 |

| Male infertility (%) | 1 (50) |

| Consanguineous parents (%) | 7 (50) |

Table 2.

CLCN2 mutations of the reported patients with CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy

| Case | Exon | DNA | Protein | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | c.61dup | p.Leu21ProfsTer27 | Homozygous |

| 2 | – | c.1412G > A | p.Arg471His | Homozygous |

| 3 | – | – | p.Glu475LysfsTer79 | Homozygous |

| 4 | – | – | p.Leu435ArgfsTer7 | Compound heterozygous |

| 5 | 16 | c.1769A > C | p.His590Pro | Homozygous |

| 6 | – | c.1113delinsACTGCTCAT | p.Ser375CysfsX6 | Homozygous |

| 7 | – | c.1507G > A | p.Gly503Arg | Homozygous |

| 8 | 15 | c.709G > A | p.Trp570X | Homozygous |

| 9 | 15 | c.1709G > A | p.Trp570X | Homozygous |

| 10 | 4 | c.430_435del | p.Leu144_Ile145del | Homozygous |

| 11 | 11; 2 to part of 6 | c.1143delT; c.64–1107_639del | p.Gly382AlafsX34; p.Met22LeufsX5 | Heterozygous; heterozygous |

| 12 | 14 | c.1499C > T | p.Ala500Val | Homozygous |

| 13 | 8 | c.828dupG | p.Arg277AlafsX23 | Homozygous |

| 14 | 20 | c.2257C > T | p.Arg753Ter | Homozygous |

1. Hoshi et al. [2018]

2–4. Zeydan et al. [2017]

5. Giorgio et al. [2017]

6. Hanagasi et al. [2015]

7. Di Bella et al. [2014]

8–13. Depienne et al. [2013]

14. The case of our study

Cerebellar ataxia is a predominant finding and is the most common initial symptom of this disease. The presentation of cerebellar ataxia presents varied, including gait ataxia, intention tremor (commonly in the hands), nystagmus, dysmetria and dysarthria. The neurologic deficits are mild, lack specific manifestations, and are stable or have a slowly progressive course, possibly leading to a delay in diagnosis. However, as specific clinical patterns of this disease, retinopathy and male infertility may be diagnostic clues that prompt, to a certain extent, a clinical suspicion of CC2L. The diagnosis relies on confirmatory genetic testing. Generally, CC2L has a favourable prognosis, and no disease-related blindness, permanent mobility impairment or deaths have been reported to our knowledge. To date, there is no specific treatment for CC2L, and only supportive care is available [2].

Conventional MRI techniques

The brain abnormalities showed confluent, symmetric T2-weighted hyperintensities along the fiber tracts, without contrast enhancement. The major criteria are the involvement of the posterior limbs of the internal capsules, cerebral peduncles, and middle cerebellar peduncles. In addition, the supportive criteria include involvement of the following: the pyramidal tracts in the pons, the central tegmental tracts in the brainstem, the superior cerebellar peduncles, decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles, corpus callosum, dentate nucleus, and other white matter of the cerebrum and cerebella [2]. The periventricular white matter is relatively unaffected. Two subclinical patients with CC2L with incidentally found leukoencephalopathies have been reported, including a 42-year-old Italian man with the onset of azoospermia [13], and a 52-year-old Moroccan woman presenting with optic atrophy [9]. This finding suggested that the brain MRI abnormalities of CC2L might precede the neurologic symptoms. CC2L has a quite distinct MRI phenotype that may facilitate early genetic testing and diagnosis. This disease can be identified from the inherited vasculopathies with white matter involvement, inflammatory demyelinating diseases or certain leukodystrophies that show multifocal white matter changes or contrast-enhancing lesions.

Advanced MRI techniques

DWI shows hyperintensity in the pathological areas, with restricted diffusion in the ADC maps of some patients [1, 14–16] and with no restricted diffusion in others [9, 13], including in the patient in the current study. This discrepancy may be explained in part by the differences in the free water content, which could be influenced by the size of the myelin vacuoles and extracellular space in the lesions [1, 13]. In the ClC-2 KO brain, the vacuole size slowly increased with the age of the mice [3]. The longitudinal data describing the radiological course of CC2L are limited. In a 42-year-old man with a homozygous missense CLCN2 mutation, the leukodystrophic pattern was unchanged over a 2-year follow-up [13]. However, in a 22-month-old female with a homozygous frameshift CLCN2 mutation, abnormal signals had spread at a 4-month follow-up DWI, and some of those abnormalities had disappeared at a 10-month follow-up [16].

Decreased diffusion anisotropy was detected in various brain regions on the FA map of the patient, which was more widespread than the WMHI on the conventional MRI. Interestingly, some of the abnormal regions highly overlapped with the constituents of the inputs and outputs of the red nucleus [17–19], namely, dentate-rubro-thalamo-cortical tracts (DRT) and corticorubrospinal tracts (CRST) respectively. Patients suffering from lesions involving the aforementioned tracts could present with ataxia and tremor [20–22]. Therefore we speculated that there may be a link between the cerebellar ataxia of the patient and the involvement of red nucleus connectivity. This hypothesis needs to be confirmed with further studies based on a larger number of cases. Additionally, our results suggested that the FA map was able to demonstrate the subtle changes of CC2L that may be missed with conventional MRI. This could be a valuable tool for the early diagnosis of subclinical patients.

DTT showed that the cerebral peduncle and middle cerebellar peduncle of the patient were obviously thinner than those of the controls, and the FN values decreased. This observation raises the question of whether axonal degeneration or damage exists in pathological tracts. However, further investigation of the directional diffusivities of these structures revealed increased RD and unchanged AD. Increased RD and decreased AD are markers of myelin and axonal injury, respectively [23–25]. Therefore, our results suggest that there was damaged myelin integrity and unaffected axons, supporting the observations in ClC-2 KO mouse [3, 26]. A possible explanation for the thinned pathological tracts on DTT is that the markedly affected tracts were incapable of being tracked under the present processing threshold (FA > 0.20, fiber angulation < 70°) due the pressure of the prominent vacuoles. The relative preservation of axons could partly explain the mild neurologic symptoms of the patient despite significant white matter involvement. However, we could not rule out the possibility of accompanying mild axonal damage. Human neuropathology should be performed to verify our findings.

In contrast, decreased AD and FN but unchanged RD were observed in the optic nerves of the patient, suggesting optic atrophy and the preservation of myelin. In addition, pigment epithelium atrophy and choroidal capillary atrophy was observed on FFA of the patient, as well as macular atrophy on OCT. These results are in line with those of previous studies, which suggest that Clcn2 mutations could lead to pigment epithelium cells dysfunction and cause a severe early-onset retinal degeneration, and no vacuole was observed in the optic nerves [3, 26, 27]. The vacuolation of the optic nerve of Cx47/32 double-KO mice could be suppressed by inhibiting optic nerve activity [3]. Therefore, it was suggested that the absence of vacuolation in the optic nerves of ClC-2 KO mice was the result of the severe retinal degeneration and the simultaneous reduction of optic nervous electric activity [3]. Furthermore, the macular atrophy and choroidal capillary atrophy of the patient, which have not been previously reported, may be kinds of disuse atrophy secondary to the retinal degeneration.

We are aware of some limitations of this study. DTI analysis was performed in only one CC2L case and on a deficient number of controls, which limits the strength of the study. The region of interest (ROI)-based method is commonly used in case studies, but it is hypothesis-driven and cannot be used for whole-brain analysis.

In conclusion, CC2L is a rare condition characterized by diffuse edema involving specific fiber tracts passing through the brainstem. The distinct MRI patterns could be a strong indication for CLCN2 gene analysis. The findings of our study may facilitate the understanding of the pathophysiology and clinical symptoms of the disease.

Additional file

Table S1. describe results of fractional anisotropy measurement, and Table S2 describe results of fiber number, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity measurement. (docx 21 kb) (DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient’s family for their participation and help.

Abbreviations

- AD

Axial diffusivity

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- CBS

Cystathionine beta-synthase

- CC2L

CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy

- CRST

Corticorubrospinal tracts

- CST

Corticospinal tract

- DRT

Dentate-rubro-thalamo-cortical tracts

- DSCP

Decussation of superior cerebellar peduncle

- DTI

Diffusion tensor imaging

- dTPF

Dorsal transverse pontine fiber

- DTT

Diffusion tensor tractography

- DWI

Diffusion weighted imaging

- FA

Fractional anisotropy

- FN

Fiber number

- KO

Knocked out

- LKPAT

Leukoencephalopathy with ataxia

- MCP

Middle cerebellar peduncle

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RD

Radial diffusivity

- ROI

Region of interest

- vTPF

Ventral transverse pontine fiber

- WMHI

White matter hyperintensity

Authors’ contributions

TL, WQ, FP, JL and ZL contributed to the obtaining and interpreting of the clinical information. SC, ZG and TL reviewed the MRI. ZG processed and measured the DTI data. HC analysed the ophthalmologic examination. LP managed the gene sequencing and interpreted the results. ZG and TL prepared the manuscript. WQ, SC and ZL reviewed the whole paper, figure and legend and supplemental materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701172).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. The funding body did not participate in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report has been approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Third Affiliated hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her family for genetic analysis and publication of this case.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhuoxin Guo and Tingting Lu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhuoxin Guo, Email: guo_z_x@163.com.

Tingting Lu, Email: lutingting_sysu@163.com.

Lisheng Peng, Email: lisheng79peng@163.com.

Huanhuan Cheng, Email: cheng544657716@163.com.

Fuhua Peng, Email: pengfuhua93@163.com.

Jin Li, Email: lijin8102@163.com.

Zhengqi Lu, Email: lzq1828@protonmail.com.

Shaoqiong Chen, Email: csq_q@yahoo.com.

Wei Qiu, Email: qiuwei120@vip.163.com.

References

- 1.Depienne C, Bugiani M, Dupuits C, Galanaud D, Touitou V, Postma N, et al. Brain white matter oedema due to ClC-2 chloride channel deficiency: an observational analytical study. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12:659–668. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Knaap MS, Depienne C, Sedel F, Abbink TEM. CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2015. [PubMed]

- 3.Blanz J, Schweizer M, Auberson M, Maier H, Muenscher A, Hubner CA, et al. Leukoencephalopathy upon disruption of the chloride channel ClC-2. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6581–6589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0338-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Xu M, Kong Q, Sun P, Yan F, Tian W, et al. Molecular medicine reports. 2017. Research and progress on ClC2 (review) pp. 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poroca DR, Pelis RM, Chappe VM. ClC channels and transporters: structure, physiological functions, and implications in human chloride Channelopathies. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:151. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jentsch TJ, Pusch M. CLC chloride channels and transporters: structure, function, physiology, and disease. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1493–1590. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholl UI, Stolting G, Schewe J, Thiel A, Tan H, Nelson-Williams C, et al. CLCN2 chloride channel mutations in familial hyperaldosteronism type II. Nat Genet. 2018;50:349–354. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaitan-Penas H, Apaja PM, Arnedo T, Castellanos A, Elorza-Vidal X, Soto D, et al. Leukoencephalopathy-causing CLCN2 mutations are associated with impaired cl(−) channel function and trafficking. J Physiol. 2017;595:6993–7008. doi: 10.1113/JP275087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giorgio Elisa, Vaula Giovanna, Benna Paolo, Lo Buono Nicola, Eandi Chiara Maria, Dino Daniele, Mancini Cecilia, Cavalieri Simona, Di Gregorio Eleonora, Pozzi Elisa, Ferrero Marta, Giordana Maria Teresa, Depienne Christel, Brusco Alfredo. A novel homozygous change ofCLCN2(p.His590Pro) is associated with a subclinical form of leukoencephalopathy with ataxia (LKPAT) Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2017;88(10):894–896. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoegg-Beiler MB, Sirisi S, Orozco IJ, Ferrer I, Hohensee S, Auberson M, et al. Disrupting MLC1 and GlialCAM and ClC-2 interactions in leukodystrophy entails glial chloride channel dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3475. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirisi S, Elorza-Vidal X, Arnedo T, Armand-Ugon M, Callejo G, Capdevila-Nortes X, et al. Depolarization causes the formation of a ternary complex between GlialCAM, MLC1 and ClC-2 in astrocytes: implications in megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:2436–2450. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capdevila-Nortes X, Jeworutzki E, Elorza-Vidal X, Barrallo-Gimeno A, Pusch M, Estevez R. Structural determinants of interaction, trafficking and function in the ClC-2/MLC1 subunit GlialCAM involved in leukodystrophy. J Physiol. 2015;593:4165–4180. doi: 10.1113/JP270467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Bella D, Pareyson D, Savoiardo M, Farina L, Ciano C, Caldarazzo S, et al. Subclinical leukodystrophy and infertility in a man with a novel homozygous CLCN2 mutation. Neurology. 2014;83:1217–1218. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanagasi HA, Bilgic B, Abbink TE, Hanagasi F, Tufekcioglu Z, Gurvit H, et al. Secondary paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia associated with CLCN2 gene mutation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21:544–546. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeydan B, Uygunoglu U, Altintas A, Saip S, Siva A, Abbink TEM, et al. Identification of 3 novel patients with CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy due to CLCN2 mutations. Eur Neurol. 2017;78:125–127. doi: 10.1159/000478089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshi M, Koshimizu E, Miyatake S, Matsumoto N, Imamura A. A novel homozygous mutation of CLCN2 in a patient with characteristic brain MRI images - a first case of CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy in Japan. Brain Dev. 2019;41:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palesi F, Tournier JD, Calamante F, Muhlert N, Castellazzi G, Chard D, et al. Contralateral cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways with prominent involvement of associative areas in humans in vivo. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:3369–3384. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0861-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milardi D, Cacciola A, Cutroneo G, Marino S, Irrera M, Cacciola G, et al. Red nucleus connectivity as revealed by constrained spherical deconvolution tractography. Neurosci Lett. 2016;626:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benagiano V, Rizzi A, Lorusso L, Flace P, Saccia M, Cagiano R, et al. The functional anatomy of the cerebrocerebellar circuit: a review and new concepts. J Comp Neurol. 2018;526:769–789. doi: 10.1002/cne.24361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang Sung Ho, Kwon Hyeok Gyu. Change of Neural Connectivity of the Red Nucleus in Patients with Striatocapsular Hemorrhage: A Diffusion Tensor Tractography Study. Neural Plasticity. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/679815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marek M, Paus S, Allert N, Madler B, Klockgether T, Urbach H, et al. Ataxia and tremor due to lesions involving cerebellar projection pathways: a DTI tractographic study in six patients. J Neurol. 2015;262:54–58. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez LI, Bronstein AM, Gresty MA, Boulay EPGD, Rudge P. Clinical and MRI correlates in 27 patients with acquired pendular nystagmus. Brain A Journal of Neurology. 1996;119:465. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budde Matthew D., Kim Joong Hee, Liang Hsiao-Fang, Schmidt Robert E., Russell John H., Cross Anne H., Song Sheng-Kwei. Toward accurate diagnosis of white matter pathology using diffusion tensor imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;57(4):688–695. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song SK, Sun SW, Ju WK, Lin SJ, Cross AH, Neufeld AH. Diffusion tensor imaging detects and differentiates axon and myelin degeneration in mouse optic nerve after retinal ischemia. NeuroImage. 2003;20:1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song S-K, Sun S-W, Ramsbottom MJ, Chang C, Russell J, Cross AH. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. NeuroImage. 2002;17:1429–1436. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards MM, Marin de Evsikova C, Collin GB, Gifford E, Wu J, Hicks WL, et al. Photoreceptor degeneration, azoospermia, leukoencephalopathy, and abnormal RPE cell function in mice expressing an early stop mutation in CLCN2. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2010;51:3264–3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bosl MR, Stein V, Hubner C, Zdebik AA, Jordt SE, Mukhopadhyay AK, et al. Male germ cells and photoreceptors, both dependent on close cell-cell interactions, degenerate upon ClC-2 cl(−) channel disruption. EMBO J. 2001;20:1289–1299. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. describe results of fractional anisotropy measurement, and Table S2 describe results of fiber number, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity measurement. (docx 21 kb) (DOCX 20 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. The funding body did not participate in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.