Abstract

Objective

Intrathecal baclofen treatment is used for the treatment of dystonia in patients with severe dyskinetic cerebral palsy; however, the current level of evidence for the effect is low. The primary aim of this study was to provide evidence for the effect of intrathecal baclofen treatment on individual goals in patients with severe dyskinetic cerebral palsy.

Methods

This multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial was performed at 2 university medical centers in the Netherlands. Patients with severe dyskinetic cerebral palsy (Gross Motor Functioning Classification System level IV–V) aged 4 to 24 years who were eligible for intrathecal baclofen were included. Patients were assigned by block randomization (2:2) for treatment with intrathecal baclofen or placebo for 3 months via an implanted microinfusion pump. The primary outcome was goal attainment scaling of individual treatment goals (GAS T score). A linear regression model was used for statistical analysis with study site as a covariate. Safety analyses were done for number and type of (serious) adverse events.

Results

Thirty‐six patients were recruited from January 1, 2013, to March 31, 2018. Data for final analysis were available for 17 patients in the intrathecal baclofen group and 16 in the placebo group. Mean (standard deviation) GAS T score at 3 months was 38.9 (13.2) for intrathecal baclofen and 21.0 (4.6) for placebo (regression coefficient = 17.8, 95% confidence interval = 10.4‐25.0, p < 0.001). Number and types of (serious) adverse events were similar between groups.

Interpretation

Intrathecal baclofen treatment is superior to placebo in achieving treatment goals in patients with severe dyskinetic cerebral palsy. ANN NEUROL 2019

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as a group of developmental disorders of movement and posture attributed to nonprogressive disturbances that have occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain. Motor impairments are often accompanied by nonmotor symptoms such as epilepsy, secondary musculoskeletal problems, and disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication, and/or behavior.1 The reported prevalence is 2.11 per 1,000 live births (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.98–2.25) in high‐income countries, and 2.9 to 3.7 per 1,000 live births in low‐income countries.2, 3, 4 CP is classified into 3 types based on the predominant motor disorder: spastic, dyskinetic, and ataxic. After spastic CP (80%), dyskinetic CP is the second most common type of CP.1

Dyskinesia is the predominant motor disorder in 9 to 15% of CP patients.2, 4 It is characterized by involuntary, uncontrolled, recurring, occasionally stereotyped movements with fluctuating muscle tone.5 Dyskinesia is subdivided into dystonia and choreoathetosis. Dystonia is characterized by slow involuntary movements, distorted voluntary movements, and abnormal postures due to sustained or intermittent muscle contractions. Tone is fluctuating but easily increased (hypertonia).5 Choreoathetosis is featured by fast hyperkinetic movements and tone fluctuation (mainly hypotonia).5

The majority of dyskinetic CP patients are severely affected and classified in Gross Motor Functioning Classification System (GMFCS) levels IV and V. These GMFCS levels correspond with having no walking ability.6 Dystonia and choreoathetosis are frequently present simultaneously in dyskinetic CP, but dystonia is usually more prominent.6 Most treatment options for dyskinetic CP are aimed at decreasing dystonia.6

When efficacy of oral medication is insufficient, options requiring neurosurgical intervention such as intrathecal baclofen (ITB) treatment or deep brain stimulation (DBS) are the next step in treatment of dyskinetic CP.6, 7 DBS is effective in primary dystonia, but results in dyskinetic CP have been conflicting.6, 7 Although there is some evidence for the effectiveness of ITB in reducing spasticity in CP, mainly from short‐term single‐bolus trial studies, to date there are only low‐quality, noncontrolled studies, producing low‐level evidence for ITB in the reduction of dystonia.7, 8 Most dyskinetic CP patients for whom ITB is considered aim to gain improvement of dressing, positioning, transfers, pain, and comfort.9 There is currently inadequate evidence for the effect of ITB in dyskinetic CP on achievement of individual goals related to quality of life, activities of daily life, and participation.7

The primary aim of this study is to provide evidence for the effect of ITB on individual treatment goals in patients with severe dyskinetic CP. Secondary aims are to address the effect on dystonia, spasticity, range of motion (ROM), pain, comfort, and treatment‐related complications.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, located at Free University Amsterdam University Medical Center (VUMC), Amsterdam, and the Maastricht University Medical Center (MUMC), Maastricht, the Netherlands. The study was approved by institutional review boards at both sites and by the Medical Ethical Review Committee (MERC) of Free University Amsterdam. The study protocol was previously published and provides additional information about the methods employed.10 This trial is registered with the Dutch Trial Register, number NTR3642.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the pediatric rehabilitation and/or child neurology outpatient clinic at both sites. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. Patients and/or parents or legal guardians gave written informed consent. Measurements were discontinued at signs of discomfort due to the measurements.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

GMFCS = gross motor functioning classification system; ITB = intrathecal baclofen treatment; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

At the start of the study in January 2013, participation in the study was with the result that not all eligible patients were included in the trial, although they received ITB treatment. The Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) advised the MERC that the study involved an experimental pharmaceutical therapy because the effect of ITB in dyskinetic CP patients was not conclusively established. The MERC decided that from December 2014, ITB treatment for dyskinetic CP patients could only be provided in the study context, by which all eligible patients were automatically included in the trial, and ITB was not offered as regular treatment.

Randomization and Masking

Patients were assigned by block randomization (2:2) to receive either ITB or intrathecal placebo via an implanted microinfusion pump (Synchromed II; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). Randomization was stratified by study site. The last 4 patients combined from both sites were randomized in 1 block to assure even groups. All but the pharmacist preparing the study medication were masked for group allocation. A list of group allocation was stored at the pharmacy. Closed envelopes were provided for the study staff to be used for unmasking in case of emergency and after final measurements. Outcome assessors remained masked until after statistical analysis was completed.

Procedures

The pump was implanted in a subfascial or subcutaneous pocket in the lower abdomen depending on local routines and patient characteristics (mostly nutritional status). Considering previous clinical observations suggesting that the site of action for ITB in dyskinetic CP is intracranial,11 the catheter tip was aimed to be placed at the midcervical level (C4). Best‐practice surgical techniques were applied, including techniques to minimize complications such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage (48 hours of horizontal bed rest, pressure bandage postsurgery) and infection (preoperative washing with antibacterial soap [until 2017] and from 2018 impregnation/bathing of pump, catheter, and pocket with vancomycin, combined with 24 hours intravenous cefazolin starting 30 minutes before first skin incision).12, 13

During the 3 months after pump implantation, the placebo group received sodium chloride (0.9%) and the ITB group received baclofen in the intrathecal pump system. Patients were instructed to continue taking their regular oral medication influencing muscle tone, such as baclofen or trihexyphenidyl, at the preoperative dose during the whole study.

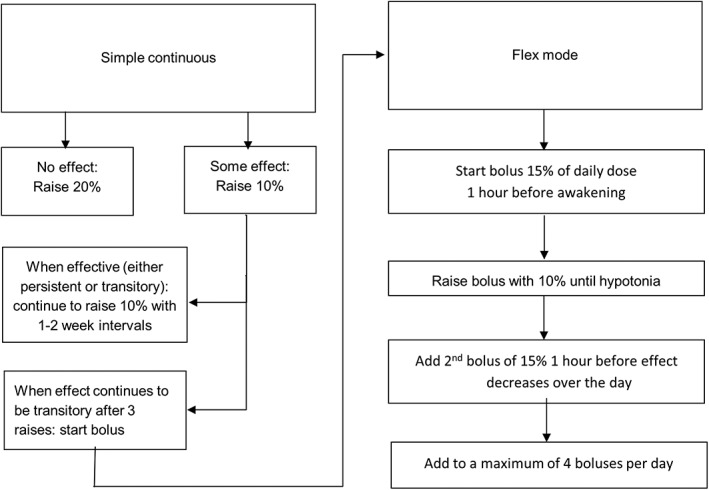

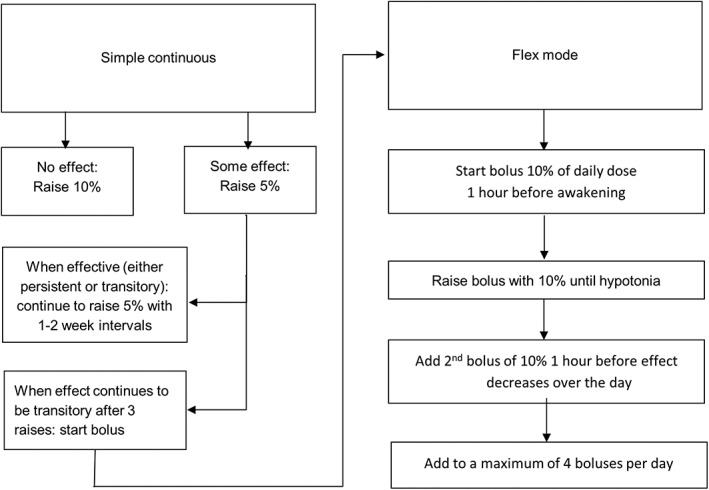

The starting dose of intrathecal treatment was 50μg per 24 hours for all patients. Dose increments were applied by the treating physicians, who were not study assessors, guided by a dosing schedule developed for the study and based on clinical experience (Table 2; Figs 1 and 2). Dose was increased at least 10 times, except if the effect was deemed satisfactory earlier and personal goals were achieved at a fewer number of increments.

Table 2.

IDYS Trial Dosing Schedule for ITB in Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy

| Phase of Dose Finding | Aged 8 yr and Older (Fig 3) | Aged 7 yr and Younger (Fig 4) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Start treatment at simple continuous mode at 50μg/day |

|

|

| 2. Starting to notice effect |

|

|

| 3. Bolus added |

|

|

ITB = intrathecal baclofen treatment.

Figure 1.

Dosing Schedule for age 8 years and older.

Figure 2.

Dosing schedule for age 7 years and younger.

Measurements were performed prior to pump implantation and 3 months after. Unmasking was done by the treating physician right after finalization of the 3‐month measurements.

Outcomes

The following patient characteristics were registered: age, sex, GMFCS level, Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) level, level of comprehension of spoken language (determined with the Computer‐Based Instrument for Low motor Language Testing (C‐BiLLT),14 and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) classification.10 Treatment characteristics registered were catheter tip position and dosage after 3 months.

The primary outcome measure, achievement of individual goals, was assessed with goal attainment scaling (GAS).10 Before pump implantation, individual goals were identified by questioning parents and patients. The current situation and the desired outcome for 2 to 3 goals were determined and used to extrapolate all other possible outcomes on the GAS scale. An example of a GAS scale is given in Table 3. At follow‐up after 3 months, goal attainment was assessed by the same blinded assessor who questioned parents and patients about the current situation of the previously set goals. The outcome was scored for each separate goal. From these separate scores, a single aggregated T score was produced using a standardized mathematic formula.10 Subjects who attain a GAS T score of ≥50 achieved their goals.10 Furthermore, the number of achieved and partially achieved goals was assessed. Clinical relevance was defined as achievement of at least 1 goal.4

Table 3.

Goal Attainment Scaling: Typical Example of an Individual Goal

| Assignment | How Comfortably Can Your Child Sit in His Own Wheelchair? | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal attainment level | ||

| −3 | Deterioration | He is always uncomfortable when sitting in wheelchair (VAS for discomfort = 9–10) |

| −2 | Equal to start | He is uncomfortable when sitting in wheelchair (VAS = 7–8) |

| −1 | Goal partially achieved | Sometimes he is comfortable and sometimes not (VAS = 5–6) |

| 0 | Desired outcome: goal achieved | He is usually fairly comfortable when sitting in wheelchair (VAS = 3–4) |

| 1 | Somewhat better than desired outcome | He is usually comfortable when sitting in wheelchair (VAS = 2) |

| 2 | Much better than desired outcome | He is always comfortable when sitting in wheelchair (VAS = 1) |

VAS = visual analog scale.

Treatment goals were classified in the domains defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health—Children and Youth version (ICF‐CY), developed by the World Health Organization: body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors.15

Secondary outcome measures were assessed both at baseline and at 3 months after pump implantation.

Dyskinesia was measured using the Barry–Albright dystonia scale (BADS) and Dyskinesia Impairment Scale (DIS). The BADS measures dystonia in different body regions and provides a total dystonia score (range = 0–32). A difference of ≥25% compared to baseline values has been described to be clinically significant.10 The DIS measures both dystonia and choreoathetosis during rest and activities. A total DIS score and subscores for dystonia and choreoathetosis (total, rest, action) can be computed (range = 0–100%).16 It is not known what the clinically significant cutoff values for the DIS (sub)scores are. There are no test‐retest reliability studies or data on responsiveness for either measure.17 All of our assessors were trained to distinguish dystonia and choreoathetosis. Studies show moderate interrater reliability.17 Surface electromyography was initially performed with the aim to quantify dystonia by recording activation of individual muscles10 but was discontinued after interim evaluation. Technical issues made reliable assessment difficult, and measurements appeared to be stressful for patients.

Spasticity was assessed clinically and electrophysiologically. The spasticity test (SPAT) was used to assess spasticity clinically in hip adductors, knee flexors and extensors, ankle plantar flexors, and elbow extensors and flexors.10 With the SPAT, spasticity is elicited by a passive stretch of the muscle with fast velocity and is scored present when a catch is felt by the examiner. The ratio of the soleus Hoffmann reflex (H reflex) to M wave was determined, representing the spinal cord neuronal response to an afferent electric stimulus.10, 18

The degrees of passive ROM were measured for hip abduction, knee flexion, popliteal angle, ankle dorsiflexion (with flexed and extended knee), elbow flexion, and elbow extension.10

Pain and comfort were scored by parents, using a visual analog scale with scores ranging from 0 to 10. For pain, a score of 0 corresponded with “no pain” and 10 with “unsustainable pain.” For comfort, a score of 0 corresponded with “very uncomfortable” and 10 with “no discomfort.” If possible, children scored their level of comfort using a faces pain scale corresponding with scores from 0 to 6.10

The Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI) questionnaire was used to assess skills in mobility, self‐care, and social function.10, 19

Participants were asked about their thoughts about group allocation after the measurements, right before unmasking (ITB/placebo/don't know).

All adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were assessed. SAEs were submitted to an online research database (http://www.toetsingonline.nl), automatically informing the MERC. We furthermore evaluated the change in symptoms related to sleep‐related breathing disorders (SRBD) using a specific subscale of the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire.10, 20

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was calculated on the basis of the primary outcome measure: the difference in GAS T score between the placebo and ITB group after 3 months.10 It was hypothesized that the ITB group would attain a GAS T score of 50, whereas the score for the placebo group would not differ from baseline (GAS T score = 22.7). To guarantee a statistical power of 90% at a significance level of 5%, a total of 13 patients per group was needed. Because several complications occurred during the study, inclusion was expanded to 18 patients per group to prevent the study from becoming underpowered.

Baseline data were described with summary statistics. For normally distributed outcome data, linear regression methods were used to compare groups. Baseline values (only applicable for secondary outcome measures) and study site were included as covariates. Where normal distribution was not found, nonparametric methods (Mann–Whitney U test) were used. Safety analyses for number and type of (S)AEs were performed with Pearson χ2 test or Mann–Whitney U test. All statistical analyses were performed before group allocation was revealed. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22. GAS T scores and (S)AEs were regularly monitored during the study by an independent DSMB.

Results

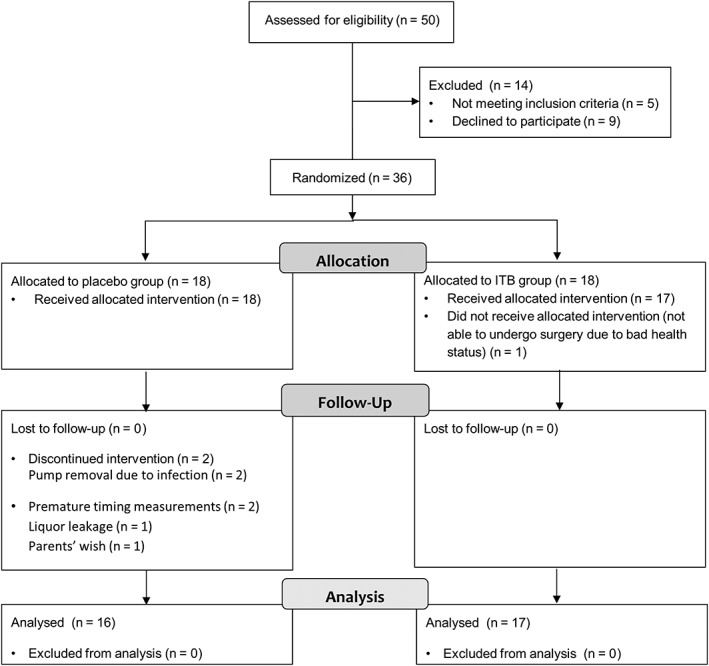

From January 1, 2013, to March 31, 2018, a total of 36 patients (30 in Amsterdam University Medical Center, 6 in MUMC) were randomized over the 2 groups, providing 18 patients per group. The trial profile is presented in Figure 3. One patient was unmasked before the end of the study period during presentation at the emergency room because of swelling over the pump, possibly due to liquor leakage, 10 days postimplantation. Because knowledge on group allocation could influence outcome, scores for GAS, pain, and comfort were not rated for this patient and therefore were not included in the final analysis. For this patient, all other outcome measures were assessed by a still‐masked assessor and used for analysis. Brain MRI was available for all patients at the time of inclusion, but for 2 patients imaging was not available for scoring due to technical problems. Two patients (1 in each group) did not tolerate the H reflex, and this measurement was not repeated at their follow‐up. The catheter tip was placed at a lower level than the aimed C4 due to technical surgical issues in 2 patients in the ITB group and in 4 patients in the placebo group.

Figure 3.

Trial profile. ITB = intrathecal baclofen.

Patient characteristics were similar across groups (Table 4). Treatment characteristics were similar across groups, except for a significant difference between groups in usage of bolus dosing (p = 0.02). Bolus dosing was more frequently applied in ITB (59%) compared to placebo (6%). Mean dosage after 3 months was 179μg per 24 hours (standard deviation [SD] = 206, range = 80–966μg) for ITB compared to 170μg per 24 hours (SD = 70, range = 55–300μg) for placebo (p = 0.24).

Table 4.

Baseline Characteristics of the Intrathecal Baclofen Treatment and Placebo Groups

| Characteristic | ITB, n = 18 | Placebo, n = 18 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13 (72%) | 12 (67%) |

| Female | 5 (28%) | 6 (33%) |

| Age, yr | 13.8 (4.3) | 14.7 (4.3) |

| GMFCS | ||

| IV | 8 (44%) | 5 (28%) |

| V | 10 (56%) | 13 (72%) |

| MACS | ||

| III | 2 (11%) | 1(5%) |

| IV | 4 (22%) | 5 (28%) |

| V | 12 (67%) | 12 (67%) |

| C‐BiLLTa | 65 (16)b | 64 (25)c |

| Catheter tipd | ||

| Th3 or higher | 15 (88%) | 13 (72%) |

| Th4 or lower | 2 (12%) | 5 (28%) |

| MRI patterna | ||

| Basal ganglia/thalamic lesions | 12 (70%) | 10 (59%) |

| Kernicterus/globus pallidus | 2 (12%) | 2 (12%) |

| Multicystic encephalomalacia | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | 3 (18%) | 4 (23%) |

Data are presented as n (%) or as mean (standard deviation).

Data not available for all randomized patients.

Age equivalent of 53 to 55 months.

Age equivalent of 50 to 52 months.

Data available for all implanted pumps.

C‐BiLLT = Computer Based Instrument for Low motor Language Testing; GMFCS = Gross Motor Functioning Classification System; ITB = intrathecal baclofen; MACS = Manual Ability Classification System; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; Th = thorecal.

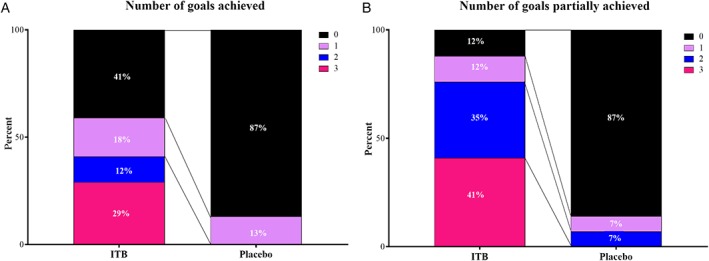

GAS T scores at 3 months were significantly different between groups in favor of ITB (regression coefficient [RC] = 17.8, 95% CI = 10.4–25.0, effect size [β] = 0.672, p < 0.001) (Table 5). Significant differences were found between groups for percentages of numbers of goals achieved (Fig 4A, p = 0.005) and partially achieved (Fig 4B, p < 0.001). In the ITB group, 59% achieved at least 1 goal, which was considered clinically relevant, compared to 13% in the placebo group. Number needed to treat to achieve at least 1 goal was 2.2. Age and sex as confounders did not influence the effect. The type of treatment goals was similar in both groups (Table 6).

Table 5.

Differences in Outcomes between Intrathecal Baclofen Treatment and Placebo Groups

| Outcomes | ITB, n = 17 | Placebo, n = 16 | RC (95% CI) | Effect Size (β) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 mo | Baseline | 3 mo | ||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| GAS T scorea | NA | 38.9 (13.2) | NA | 21.0 (4.6) | 17.8 (10.4–25.0) | 0.672 | 0.00b |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| DIS | |||||||

| Total | 43% (9%) | 40% (10%) | 41% (13%) | 45% (11%) | −6% (−12% to 0%) | −0.28 | 0.045b |

| Dystonia | |||||||

| Total | 67% (11%) | 64% (15%) | 66% (18%) | 72% (11%) | −8% (−14% to −2%) | −0.29 | 0.017b |

| Rest | 58% (16%) | 55% (23%) | 59% (22%) | 68% (12%) | −12% (−22% to −2%) | −0.32 | 0.013b |

| Activity | 73% (12%) | 70% (14%) | 72% (15%) | 75% (12%) | −5% (−13% to 3%) | −0.20 | 0.19b |

| Choreoathetosis | 19% (15%) | 15% (13%) | 15% (17%) | 17% (20%) | — | — | 0.83c |

| BADS | 20.6 (8.9) | 19.1 (5.9) | 19.9 (7.5) | 20.4 (4.4) | −1.50 (−4.9 to 1.9) | −0.146 | 0.38b |

Data are presented as mean (SD). Not all patients were able to perform all items of the DIS standardized video protocol. When at one measurement moment an item could not be scored, this item was excluded from analysis.

Data not available for all patients.

Linear regression analysis.

Mann–Whitney U test.

BADS = Barry–Albright Dystonia Scale; CI = confidence interval; DIS = Dyskinesia Impairment Scale; GAS = goal attainment scaling; ITB = intrathecal baclofen; NA = not applicable; RC = regression coefficient.

Figure 4.

(A) Differences in percentage of goal attainment scaling (GAS) goals achieved. (B) Differences in percentage of GAS goals partially achieved for intrathecal baclofen treatment (ITB) and placebo group. ITB = intrathecal baclofen. Fig. 4A, p = 0.005. Fig. 4B, p < 0.001. The percentage of patients (partially) achieving 0, 1, 2, or 3 goals is shown for the ITB and placebo group.

Table 6.

Treatment Goals

| ICF‐CY Level Goal | Total | ITB, n = 18 | Placebo, n = 18 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total/Evaluated NR of Goals | Total/Evaluated NR of Goals | NR [partially] Achieved Goals, n (%) | Total/Evaluated NR of Goals | NR [partially] Achieved Goals, n (%) | ||

| Body functions and structures | 16/14 | 6/6 | 5 (83) | 10/8 | 1 (13) | 0.01a |

| Sleep | 5/5 | 1/1 | 1 (100) | 4/4 | 1 (25) | |

| Pain/ comfort | 7/6 | 4/4 | 3 (75) | 3/2 | 0 (0) | |

| Alertness | 2/1 | 0 | NA | 2/1 | 0 (0) | |

| Weight | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1 (100) | 0 | NA | |

| Wearing AFO | 1/1 | 0 | NA | 1/1 | 0 (0) | |

| Activities and participation | ||||||

| Communication | 6/6 | 2/2 | 0 (0) | 4/4 | 1 (25) | NA |

| Using communication device | 6/6 | 2/2 | 0 (0) | 4/4 | 1 (25) | |

| Mobility | 36/32 | 18/18 | 12 (67) | 18/14 | 1 (7) | 0.001a |

| Changing position | 5/5 | 3/3 | 2 (67) | 2/2 | 0 (0) | |

| Sitting | 8/5 | 3/3 | 3 (100) | 5/2 | 0 (0) | |

| Moving around | 11/11 | 7/7 | 5 (71) | 4/4 | 0 (0) | |

| Hand and arm use | 12/11 | 5/5 | 2 (40) | 7/6 | 1 (17) | |

| Environmental factors | ||||||

| Caregiving by others | 46/41 | 26/23 | 18 (78) | 20/18 | 0 (0) | <0.001a |

| Dressing | 28/25 | 14/12 | 9 (75) | 14/13 | 0 (0) | |

| General caregiving | 1/0 | 0 | NA | 1/0 | NA | |

| Washing | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3 (75) | 0 | NA | |

| Hygienic care | 13/12 | 8/7 | 6 (86) | 5/5 | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 104/93 | 52/49 | 35 (71) | 52/44 | 3 (7) | |

Comparison of number of partially achieved goals between groups with Mann–Whitney U test.

AFO = ankle foot orthosis; ICF‐CY = International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—Children and Youth version; ITB = intrathecal baclofen; NA = not applicable; NR = number.

Table 5 shows the results for DIS and BADS (sub)scores. At 3 months, no significant difference between groups was seen for the BADS. The total DIS (RC = −6%, ES = −0.28, p = 0.045), DIS dystonia subscale (RC = −8%, ES = −0.29, p = 0.017), and dystonia during rest subscale (RC = −12%, ES = −0.32, p = 0.013) were significantly more favorable with ITB.

There was no significant correlation between DIS (sub)score(s) and GAS T scores or between changes (pre/post) in DIS (sub)score(s) and GAS T scores.

There were no significant differences between groups for any of the other secondary outcome measures, either in the domain of body functions and structures (spasticity, pain, comfort) or in the domain of activities and participation (PEDI). Parents’ thoughts on group allocation were correct for most patients in both groups (ITB = 76%, placebo = 87%).

There were a total of 23 AEs and 6 SAEs in 22 patients. There was no significant difference between groups for total number or type of (S)AEs (Table 7). There was also no significant difference between groups for the change in parent‐reported symptoms related to SRBD.

Table 7.

Adverse Events

| Adverse Events | ITB | Placebo | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | |||

| Total | 16 | 13 | 1.00a |

| AE | 14 | 9 | 1.00 a |

| SAE | 2 | 4 | 1.00 a |

| Type, AE/SAE | 0.84b/0.29b | ||

| Surgery/pump implantation related | |||

| Liquor leakage | 6/1 | 5/1 | |

| Pump infection | 0 | 0/2 | |

| Catheter related | 0 | 0/1 | |

| Possibly adverse drug effects | |||

| Nausea or vomiting | 2 | 1 | |

| Obstipation | 0/1 | 0 | |

| Otherc | 6 | 3 | |

Mann–Whitney U test.

Pearson χ2 test.

Other complications mainly involved infections (eg, urinary tract infection, gastrointestinal infection).

AE = adverse event; ITB = intrathecal baclofen; SAE = serious adverse event.

Discussion

We report the results of the first multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial that we are aware of on continuous ITB treatment in dyskinetic CP. Compared to placebo, ITB shows a superior effect on attainment of individual treatment goals. Furthermore, outcome for dystonia, as measured with the DIS, is slightly more favorable with ITB compared to placebo.

Individual goals are achieved significantly more often with ITB compared to placebo. Our study population involves severely affected dyskinetic CP patients with little to no motor skills (GFMCS IV and V). Treatment goals for these patients are mostly to increase comfort, decrease pain, ease caregiving, and facilitate mobility (eg, transfers and positioning).9 Standardized questionnaires on quality of life or activities and participation, which were available at the time of the study, do not adequately capture the individual problems in daily life of these patients; attainment of individual goals is therefore the most useful and meaningful way to determine treatment effects. When looking at the different categories of set goals, we saw a difference between groups in (partial) achievement of goals on the ICF‐CY level of body functions and structures, activities and participation (mobility), and environmental factors (caregiving by others). The findings from our study are in line with previous case control and case series studies and add significantly to the level of evidence for the use of ITB to improve goals in these domains.6, 7

There were significant differences between ITB and placebo for the DIS total dystonia subscale and the DIS dystonia rest subscale in favor of ITB. However, we were not able to confirm results of previous studies, which found a decrease in BADS scores with ITB.12, 21, 22, 23 Previous studies had a lower level of evidence because of the nonrandomized nonblinded study designs. We used standardized videos, and assessors were masked for both treatment allocation and timing of measurements (baseline or follow‐up). The reason for finding a difference in dystonia measured by DIS and BADS might be that the situation of measurement in the DIS is better defined than the BADS, which hypothetically can lead to better reliability and less variation in scores. However, there are no test‐retest reliability studies for either the BADS or the DIS. Considering the fluctuation of dystonia in individual patients, test‐retest reliability and sensitivity to change could be problematic for both scales.17, 21

A significant difference between groups was found for the dystonia during rest subscale, but not for the dystonia during activity subscale. This may be explained by dystonia being subject to fluctuation and aggravated by nonspecific stimuli such as emotion, stress, and intentional movement.6, 22 It is likely that, despite treatment, dystonia is still aggravated during periods of activity and possibly also stress and emotions. The exact clinical implications of the small differences within and between groups are unclear.

Choreoathetosis scores were similar between groups. We found mean choreoathetosis scores to be lower than mean dystonia scores, which is accordance with previously published findings.22, 24

DIS (sub)score(s) at 3 months and changes in DIS (sub)score(s) were not correlated with GAS T scores. A previous study by Monbaliu et al showed lower functional abilities for children with higher levels of dystonia as well as poorer scores on participation and quality of life questionnaires.24 Our hypothesis was that the effect on goal attainment would be caused by a reduction of dystonia, but this was not confirmed in our study. Fluctuation of dystonia and reliability of currently available instruments, as discussed previously, might influence this finding.

Both clinical and electrophysiological spasticity measures were not significantly different between groups. In many patients with a predominant dyskinetic movement disorder, spasticity is also present.1 In patients with spastic CP, the H reflex is found to be a feasible and objective measure to identify spinal cord neuronal response to ITB.18 Considering the findings of previous studies, spasticity was expected to decrease with ITB.18 In our patients, however, spasticity was often difficult to assess reliably because both measures used are subjective to the degree of relaxation of the patient.23 Relaxation was very difficult for most due to involuntary muscle contractions and movements that characterize dyskinesia, and therefore spasticity measures might be less reliable in this group.

Changes in ROM were similar between groups, which corresponds with previous studies.25 This is not surprising because when contractures occur, due to changes in bony structures or to muscle shortening, these problems will not improve in the short term with a decrease of muscle tone established by ITB. In the long term, however, contractures might be less progressive or stabilized with ITB, preventing worsening of contracture‐related problems in daily life.

Pain and comfort scores at 3 months were similar between groups. As most patients in our study did not report pain or comfort as a problem, improvement was not expected for these patients. However, 3 out of 4 patients on ITB who did report pain or discomfort as treatment goals partially achieved this goal compared to none in the placebo group. These last results correspond with previously published studies.25, 26, 27, 28

Most parents were correct about group allocation, which shows that changes due to ITB are indeed favorable and significantly noticeable. Parents’ thoughts on group allocation might bias outcome for GAS. We limited this effect by asking parents to describe the current situation without telling them how the baseline situation was.

Baclofen did not have an additional adverse effect on the known serious complications of pump implantation because AE and SAE were similar between groups in types and number. The frequency of adverse drug effects such as constipation and nausea or vomiting were low in our study in comparison with previous studies,.29 The majority of severely affected CP patients already experienced constipation before pump implantation. Bedrest after surgery can increase this problem further. In our study, constipation worsened in 1 of the patients on ITB requiring prolonged hospital admission. Nausea and vomiting occurred in 3 patients (2 ITB, 1 placebo). Anesthesia, surgery, the period of bedrest after surgery in patients prone to reflux might all elicit nausea and vomiting in addition to the possible adverse drug effect of baclofen. Several surgery‐related complications were seen, with symptomatic CSF leak and infection being the most frequent. We found a higher occurrence of CSF leak compared to literature and a lower incidence for infection.6 We observed 1 catheter‐related problem. Comparison with previous studies is not possible because catheter‐related problems often occur after a longer follow‐up time.

No difference was found between ITB and placebo in parent‐reported symptoms related to risk of sleep‐related breathing disorders. Apnea or hypopnea during sleep is increased with ITB in adult patients with spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis.10 Children with CP already have a higher risk of sleep‐related disorders than typically developing children.10 Hypothetically, this risk might increase even more by placing the catheter at the midcervical level, close to the breathing center. To be able to fully reject this hypothesis, studies using polysomnography are needed.

Total dosage was similar between groups. This was to be expected as both groups were required to have at least 10 dose increments during the study. More patients in the ITB group were on a bolus schedule. This can be explained by the dosing schedule we used (see Table 1; see Figs 1 and 2). If no effect is noticed, the daily dose is increased in the simple continuous mode, providing a fixed infusion rate throughout the day. Only when effect is noticed, but the effect decreases over time, will a bolus be added. Consequently, some of the patients on ITB were on the simple continuous mode, and others were on a “flex mode” in which a bolus can be included.

The study has several limitations. First, the study was powered on the primary outcome measure resulting in a relatively low number of patients needed. This limits the possibility for subgroup analysis on effect‐modifying factors. It was not possible to place the catheter tip at the aimed C4 level in some patients due to technical surgical issues. Considering the hypothesis that ITB in dyskinetic patients works intracranially, the effect in these patients might be less than when placed on a higher level. Another limitation is the short follow‐up period of 3 months. In our clinical experience, it takes several weeks to several months to find the right dosage for the individual patient. We aimed to approach the optimum dosage by requiring at least 10 increments. Still, some patients might not be on the most adequate dosage yet and others only for a short time. However, we did find a clear difference for our primary outcome measure. Furthermore, a longer period of placebo was felt to be unethical. We will perform an additional 9‐month open‐label follow‐up period for all patients. Last, assessors were blinded for treatment allocation, but we did not test whether this was successful (ie, whether they personally had an idea about treatment allocation that could have influenced their judgement). Retrospectively we asked assessors to recall whether they had thoughts on group allocation. They responded that they had no opinion on group allocation during measurements, including scoring of the GAS. During scoring of the videos, which were provided coded and in random order (mixing patients and measuring moments), they also had no idea on group allocation.

Future studies should assess long‐term effects and complications using a prospective longitudinal cohort study design. An international register, like the Australian ITB audit, could provide a good basis for such a study, ensuring sufficient patient numbers and harmonization of outcome measures.30 The achievement of individual treatment goals should be the primary focus. With a larger sample size, patient and treatment characteristics and factors on the level of body functions and structures influencing goal attainment can hopefully be identified. Furthermore, it might provide us with additional insights in optimal dosage and provide evidence for the usefulness of our dosing schedule designed for patients with dyskinetic CP, which is now based on clinical observation.

Considering the described problems in reliable measurement of dystonia, test‐retest reliability studies of the DIS and BADS are needed; furthermore, it would be useful to examine whether a shortened version of the DIS, perhaps limited to the most responsive and clinically relevant items, makes the DIS more feasible for severely affected patients with dyskinetic CP in both research and clinical practice. In addition, other measurement methods of dystonia should be explored, such as instrumented measures, which are not dependent on assessors and which can easily be applied at home or at day‐care/school to decrease provocation of stress and ensure correspondence with the daily situation.

In conclusion, we were able to provide level II evidence for the effect of ITB in pediatric and adolescent patients with severe dyskinetic CP (GMFCS IV and V) on the achievement of individual treatment goals. ITB should be considered as a treatment option in patients with severe dyskinetic CP in whom oral medication is insufficient. Treatment goals should focus on body functions and structures (such as pain or discomfort), activities and participation for mobility (such as transfers and sitting), and/or environmental factors (caregiving by others). Future studies should address the long‐term effects of ITB and factors influencing outcome, and reliable measurement of dystonia in severe dyskinetic CP.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the Phelps Stichting voor Spastici (project numbers2011037 and 99.047), het Revalidatiefonds (project number R2011032/), Kinderrevalidatie Fonds de Adriaanstichting (project number 11.02.17‐2011/0035), and het Johanna KinderFonds (project number 2011/0035‐357).

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the article. The corresponding author had full access to all study data, and all main authors (L.B., J.B., J.S.H.V., R.J.V., A.B.) had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

We thank Dr S. van der Vossen for her help in conducting measurements during the absence of L.A.B.; T. van Ams and S. de Vries for taking care of the logistics regarding study medication, appointments, and pump fillings; and H. Haberfehlner for her enthusiastic and innovative ideas.

L.B., J.B., J.S.H.V., and R.J.V. contributed to the conception and design of the study; L.B., J.B., R.J.V., and A.B. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; L.B., J.B., J.S.H.V., R.J.V., and A.B. contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures.

IDYS study group members are, from the Amsterdam University Medical Center, Free University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Laura A. Bonouvrié, MD, Jules G. Becher, MD, Annemieke I. Buizer, MD, Karin Boeschoten, Johanna J. M. Geytenbeek, PhD, Vincent de Groot, MD (Rehabilitation Medicine), Laura A. van de Pol, MD (Child Neurology), Willem J. R. van Ouwerkerk, MD, K. M. Slot, MD, S. M. Peerdeman, MD (Neurosurgery), Rob L. M. Strijers, MD (Clinical Neurophysiology), Elisabeth M. J. Foncke, MD (Neurology), Jos W. R. Twisk, PhD, Peter van de Ven, PhD (Epidemiology and Biostatistics); and from Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands: R. Jeroen Vermeulen, MD, Johan S. H. Vles, MD, Dan Soudant, MANP, Sabine Fleuren (Neurology), and Onno P. Teernstra, MD (Neurosurgery).

References

- 1. Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;109(suppl):8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oskoui M, Coutinho F, Dykeman J, et al. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55:509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murthy GV, Mactaggart I, Mohammad M, et al. Assessing the prevalence of sensory and motor impairments in childhood in Bangladesh using key informants. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:1103–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kakooza‐Mwesige A, Andrews C, Peterson S, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy in Uganda: a population‐based study. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1275–e1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krägeloh‐Mann I, Petruch U, Weber PM. SCPE reference and training manual (R&TM). Grenoble, France: Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe, 2005. Available at: http://www.scpenetwork.eu/en/r-and-t-manual/. Accessed August 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Monbaliu E, Himmelman K, Lin JP, et al. Clinical presentation and management of dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fehlings D, Brown L, Harvey A, et al. Pharmacological and neurosurgical interventions for managing dystonia in cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60:356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buizer AI, Martens BHM, Grandbois van Ravenhorst C, et al. Effect of continuous intrathecal baclofen therapy in children: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liew PY, Stewart K, Khan D, et al. Intrathecal baclofen therapy in children: an analysis of individualized goals. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonouvrié LA, Becher JG, Vles JSH, et al. Intrathecal baclofen treatment in dystonic cerebral palsy: a randomized clinical trial: the IDYS trial. BMC Pediatrics 2013;131:175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Albright AL, Barry MJ, Shagron DH, Ferson SS. Intrathecal baclofen for generalized dystonia. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43:652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Albright AL, Turner M, Pattisapu JV. Best‐practice surgical techniques for intrathecal baclofen therapy. J Neurosurg 2006;104:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konstantelias AA, Vardakas KZ, Polyzos KA, et al. Antimicrobial‐impregnated and ‐coated shunt catheters for prevention of infections in patients with hydrocephalus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Neurosurg 2015;122:1096–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geytenbeek JJ, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al. Reliability and validity of the C‐BiLLT: a new instrument to assess comprehension of spoken language in your children with cerebral palsy and complex communication needs. Augment Altern Commun 2014;30:252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . International classification of functioning, disability and health: children & youth version: ICF‐CY. 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/. Accessed August 7, 2018.

- 16. Monbaliu E, Ortibus E, Prinzie P, et al. Can the Dyskinesia Impairment Scale be used by inexperienced rater? A reliability study. Eur J Neurol 2012;17:238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stewart K, Harvey A, Johnston LM. A systematic review of scales to measure dystonia and choreoathetosis in children with dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:786–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoving MA, van Kranen‐Mastenbroek VHJM, van Raak EPM, et al. Placebo controlled utility and feasibility study of the H‐reflex and flexor reflex in spastic children treated with intrathecal baclofen. Clin Neurophysiol 2006;117:1508–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feldman AB, Haley SM, Coryell J. Concurrent and construct validity of the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. Phys Ther 1990;70:602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chervin RD, Weatherly RA, Garetz SL, et al. Pediatric sleep questionnaire: prediction of sleep apnea and outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;133:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gimeno H, Tustin K, Lumsden D, et al. Evaluation of functional goal outcomes using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) following Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) in childhood dystonia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2014;18:308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Monbaliu E, de Cock P, Ortibus E, et al. Clinical patterns of dystonia and choreoathetosis in participants with dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2016;58:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen YS, Zhou S, Cartwright C, et al. Test‐retest reliability of the soleus H‐reflex is affected by joint positions and muscle force levels. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2010;20:980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Monbaliu E, De Cock P, Mailleux L, et al. The relationship of dystonia and choreoathetosis with activity, participation and quality of life in children and youth with dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2017;21:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eek MN, Olsson K, Lindh K, et al. Intrathecal baclofen in dyskinetic cerebral palsy: effects on function and activity. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bonouvrie L, Becher J, Soudant D, et al. The effect of intrathecal baclofen treatment on activities of daily life in children and young adults with cerebral palsy and progressive neurological disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2016;20:538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bonouvrié LA, van Schie PEM, Becher JG, et al. Effects of intratheal baclofen on daily care in children with secondary generalized dystonia: a pilot study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2011;15:539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Motta F, Stignani C, Antonello CE. Effects of intrathecal baclofen on dystonia in children with cerebral palsy and the use of functional scales. J Pediatr Orthop 2008;28:213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ward A, Hayden S, Dexter M, Scheinberg A. Continuous intrathecal baclofen for children with spasticity and/or dystonia: goal attainment and complications associated with treatment. J Paediatr Child Health 2009;45:720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart K, Hutana G, Kentish M. Intrathecal baclofen therapy in paediatrics: a study protocol for an Australian multicentre, 10‐year prospective audit. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]