Abstract

Aim

We report tofacitinib efficacy and safety in Asia‐Pacific patients who participated in the rheumatoid arthritis (RA) clinical development program.

Method

This post‐hoc analysis included pooled data from patients with RA in the Asia‐Pacific region treated with tofacitinib with/without conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs in Phase (P)1, 2, 3, and long‐term extension (LTE) studies (one LTE ongoing; January 2016 data‐cut). Efficacy was assessed over 24 months in patients who received tofacitinib 5 (N = 397) or 10 (N = 382) mg twice daily or placebo (N = 243) in three P2 and five P3 studies. Endpoints included American College of Rheumatology (ACR)20/50/70 responses, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28‐4[ESR]) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) remission rates, and change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire‐Disability Index (∆HAQ‐DI). Safety data pooled over 92 months from one P1, four P2, six P3, and two LTE studies for all tofacitinib doses (N = 1464) included incidence rates (IRs) (patients with events/100 patient‐years) for adverse events (AEs) of special interest.

Results

At month 3, patients receiving tofacitinib 5/10 mg twice daily improved vs placebo in ACR20 (69.2%/77.9% vs 27.5%), ACR50 (36.9%/44.4% vs 9.5%), and ACR70 (15.1%/22.4% vs 2.7%) responses, remission rates for DAS28‐4(ESR) (8.5%/18.5% vs 2.6%) and CDAI (6.1%/12.3% vs 0.5%), and ∆HAQ‐DI (−0.5/–0.6 vs −0.1); improvements were sustained through 24 months. IRs (95% CI) were 9.4 (8.5, 10.3) for serious AEs, 9.1 (8.3, 10.1) for discontinuations due to AEs, 3.7 (3.2, 4.3) for serious infections, 5.9 (5.2, 6.7) for herpes zoster, and 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) for malignancies (excluding non‐melanoma skin cancer).

Conclusion

In Asia‐Pacific patients, tofacitinib improved signs/symptoms over 24 months. Safety over 92 months was generally consistent with global tofacitinib studies; however, infection IRs were higher in Asia‐Pacific patients.

Keywords: clinical aspects, drug treatment, rheumatoid arthritis

1. INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic and debilitating autoimmune disease characterized by systemic inflammation, persistent synovitis, and joint destruction, with a global prevalence of approximately 0.24%.1 Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of RA. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, as monotherapy or with conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), mainly methotrexate, in patients with moderately to severely active RA, have been demonstrated in global Phase 2,2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Phase 3,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and Phase 3b/413 studies of up to 24 months duration, and in long‐term extension (LTE) studies with up to 114 months of observation.14, 15, 16

The European League Against Rheumatism and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommend tofacitinib as a treatment option after inadequate response to csDMARDs.17, 18 Guidelines from the Asia‐Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology support the use of tofacitinib in patients who have an inadequate response to biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs).19 However, understanding of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with RA from the Asia‐Pacific region is largely based on post‐hoc analyses of data from patients enrolled in individual countries within the global LTE studies, including sub‐populations from Korea,20 Japan,16 and China.21 These studies indicated that tofacitinib had a stable safety profile and sustained efficacy within each Asia‐Pacific country, although an increased risk of herpes zoster (HZ) was observed in Japan and Korea vs global studies. It is of particular interest to assess RA therapies within the Asia‐Pacific region, given the demographic differences between Asia‐Pacific and Western patients with RA that may affect efficacy, and the increased background prevalence of certain infections (eg tuberculosis and hepatitis B and C) and malignancies (eg T‐cell and natural killer‐cell lymphomas) within the Asia‐Pacific region vs Western countries.19

In this post‐hoc analysis, we report tofacitinib efficacy and safety in patients with RA from the Asia‐Pacific region as a combined group within the global clinical studies. This pooled analysis included a larger number of patients than country‐specific sub‐populations to yield more precise estimates of efficacy and safety.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patients

This post‐hoc analysis included data from patients with RA enrolled in global clinical studies of tofacitinib from eight Asia‐Pacific countries: China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published.3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 22, 23 Briefly, patients were aged ≥18, or ≥20 years in Japan, with an active RA diagnosis based on the ACR 1987 Revised Criteria. Key exclusion criteria included serious chronic or recurring infections, active or inadequately treated infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a history of recurrent HZ, disseminated HZ, or disseminated herpes simplex, or a history of malignancy, except adequately treated squamous cell or basal cell skin cancers or cervical carcinoma in situ.

2.2. Study designs

Patients from the Asia‐Pacific region participated in 13 studies of tofacitinib in RA: one Phase 1 study (NCT01484561); four Phase 2 studies (NCT00550446, NCT00603512, NCT00687193, NCT01059864); six Phase 3 studies (ORAL Solo, NCT00814307; ORAL Scan, NCT00847613; ORAL Sync, NCT00856544; ORAL Standard, NCT00853385; ORAL Step, NCT00960440; ORAL Start, NCT01039688); and two LTE studies (ORAL Sequel, NCT00413699, January 2016 data‐cut; NCT00661661).

For contextualization of safety data, global data (including data from the Asia‐Pacific region) at the same data‐cut (January 2016) are presented alongside the corresponding data from the Asia‐Pacific region. In addition to the 13 global studies that included patients with RA from the Asia‐Pacific region, seven additional global studies were included: one Phase 1 (NCT01262118) and six Phase 2 (NCT00147498, NCT00413660, NCT00976599, NCT01164579, NCT01359150, NCT02147587).

Details of the individual study designs have been previously published and are summarized in Appendix S1.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards and/or Independent Ethics Committee at each study center. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.3. Efficacy endpoints

Efficacy data were pooled from three Phase 2 (NCT00550446, NCT00603512, NCT00687193) and five Phase 3 (ORAL Solo, ORAL Scan, ORAL Sync, ORAL Standard, ORAL Step) randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind studies which included patients with a prior inadequate response to DMARDs (hereafter termed the “P2/3 population”). To assess efficacy in a more homogenous patient population, the Phase 2 study NCT01059864 and the Phase 3 ORAL Start study were excluded, as patients did not have a prior inadequate response to DMARDs. To allow comparison between randomized dose groups including a placebo control, efficacy analyses did not include LTE data. Efficacy outcomes were reported through to month 24 (only patients from ORAL Scan contributed data beyond month 12) and included the proportions of patients achieving 20%, 50%, and 70% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 responses, respectively); mean Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28‐4[ESR]); the proportion of patients achieving clinical remission and low disease activity (LDA) defined according to DAS28‐4(ESR) (scores ≤2.6 and ≤3.2, respectively) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI; scores ≤2.8 and ≤10, respectively); and mean score and mean change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire‐Disability Index (HAQ‐DI), Patient Global Assessment of Arthritis (PtGA), and Physician Global Assessment of Arthritis (PGA).

2.4. Safety endpoints

Safety data were pooled from all 13 Phase 1, Phase 2, Phase 3, and LTE studies of tofacitinib which included patients with RA from the Asia‐Pacific region and included up to 92 months of tofacitinib exposure (hereafter termed the “P123LTE population”). Safety was assessed based on adverse events (AEs), physical examination, vital signs, and confirmed laboratory parameters. AEs of special interest included: serious AEs (SAEs); discontinuation due to AEs; serious infections; opportunistic infections (excluding tuberculosis); HZ (serious and non‐serious); tuberculosis; lymphoma; malignancies (excluding non‐melanoma skin cancer [NMSC]); NMSC; breast and lung cancer; major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE); gastrointestinal perforations; and deaths. Malignancy, opportunistic infection, tuberculosis, and gastrointestinal perforation events were adjudicated by separate blinded independent adjudication committees. MACE after February 2009 were adjudicated by committees of independent external experts in the fields of cardiovascular and/or neurovascular disease.

Confirmed (two sequential observations) changes in laboratory safety parameters are reported for hemoglobin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), absolute lymphocyte counts, absolute neutrophil counts, and serum creatinine. Descriptive data over time are reported for mean low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐c), high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐c), total cholesterol, and creatine kinase.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Efficacy analyses were based on the full analysis set of each study, which included all patients who were randomized and received ≥1 dose of study medication. Seven patients from the Philippines enrolled in ORAL Standard were excluded from efficacy analyses due to Good Clinical Practice compliance issues. Data are presented based on randomized treatment group (tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily, or placebo) up to month 3; beyond month 3, data are presented based on treatment sequence (tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily, placebo advancing to 5 mg twice daily, or placebo advancing to 10 mg twice daily), as patients advanced to tofacitinib from placebo at month 3 or month 6. Due to the small sample size in some groups, all analyses are descriptive in nature and general trends are described. No statistical significance was calculated and no imputation was applied for missing data.

The safety analysis set included all patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication. Data are presented based on the average tofacitinib dose (5 or 10 mg twice daily) and pooled across all tofacitinib doses. For the most common AEs, exposure‐adjusted event rates (EAERs) were derived based on the first time occurrence of each AE divided by the total number of days exposure to the study treatment. For AEs of special interest, incidence rates (IRs) were obtained based on the number of first time occurrences of each event over a given time interval, divided by the total duration of study treatment exposure censored at time of event, death, or discontinuation from the study time interval. An exact Poisson 95% confidence interval (CI) adjusted for exposure time was calculated for each IR Both EAERs and IRs are presented per 100 patient‐years of tofacitinib exposure.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

The P123LTE population included 1464 patients from the Asia‐Pacific region. Of these, 790 received an average total daily dose (TDD) of 5 mg twice daily and 674 received an average TDD of tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. The largest number of patients were enrolled from Japan (n = 556), followed by Korea (n = 291), China (n = 213), India (n = 197), Thailand (n = 64), the Philippines (n = 61), Malaysia (n = 46), and Taiwan (n = 36).

Across all tofacitinib doses at baseline, mean age was 50.5 years, 86.9% of patients were female, mean disease duration was 7.1 years, mean tender and swollen joint counts were 21.3 and 13.8, respectively, and most patients (72.1%) were receiving concomitant corticosteroid treatment. Baseline demographics and characteristics were generally similar between patients treated with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, with the exception that mean ESR (54.5 vs 64.0 mm/h, respectively) was lower in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics (P123LTE population)

| Asia‐Pacific population | Global population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tofacitinib 5 mg BID N = 790[Link] |

Tofacitinib 10 mg BID N = 674[Link] |

All tofacitinib doses N = 1464[Link] |

All tofacitinib doses N = 6301[Link] |

|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 51.6 (11.9) | 49.2 (11.6) | 50.5 (11.8) | 52.3 (11.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 679 (85.9) | 593 (88.0) | 1272 (86.9) | 5200 (82.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 22.4 (3.7) | 22.8 (4.0) | 22.6 (3.8) | 27.0 (6.4) |

| Disease duration, y, mean (range) | 7.5 (0.0‐41.0) | 6.5 (0.0‐45.0) | 7.1 (0.0‐45.0) | 8.0 (0.0‐65.0) |

| Tender joint count, mean (SD) | 19.3 (13.1) | 23.6 (16.1) | 21.3 (14.7) | 24.7 (14.6) |

| Swollen joint count, mean (SD) | 13.5 (8.9) | 14.2 (9.5) | 13.8 (9.1) | 15.3 (9.1) |

| HAQ‐DI score, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) |

| DAS28‐4(ESR) score, mean (SD) | 6.2 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.2) | 6.3 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.0) |

| ESR, mm/h, mean (SD) | 54.5 (27.9) | 64.0 (30.8) | 58.8 (29.7) | 49.2 (26.5) |

| CRP, mg/L, mean (SD) | 23.2 (25.9) | 21.1 (24.8) | 22.2 (25.4) | 18.6 (23.5) |

| RF positive, n (%) | 426 (76.9) | 445 (75.7) | 871 (76.3) | 4079 (73.2) |

| Anti‐CCP positive, n (%) | 346 (84.6) | 478 (83.4) | 824 (83.9) | 3246 (51.5) |

| Concomitant corticosteroid use at baseline, n (%) | 557 (70.5) | 498 (73.9) | 1055 (72.1) | 4202 (66.7) |

| Corticosteroid dose at baseline, mg/d, mean (SD) | 3.4 (3.3) | 4.4 (8.8) | 3.9 (6.4) | 4.0 (4.9) |

| Concomitant MTX use at baseline, n (%) | 425 (53.8) | 359 (53.3) | 784 (53.6) | 3363 (53.4) |

| Concomitant MTX dose at baseline | ||||

| <15 mg/wk | 325 (76.5) | 160 (44.6) | 485 (61.9) | 988 (29.5) |

| ≥15 mg/wk | 100 (23.5) | 199 (55.4) | 299 (38.1) | 2362 (70.5) |

| Concomitant csDMARD use at baseline, n (%) | 539 (68.2) | 506 (75.1) | 1045 (71.4) | 3825 (60.7) |

| History of medication use, n (%) | ||||

| MTX | 671 (84.9) | 548 (81.3) | 1219 (83.3) | 4998 (79.3) |

| Non‐bDMARD other than MTX | 490 (62.0) | 467 (69.3) | 957 (65.4) | 3354 (53.2) |

| bDMARD | 89 (11.3) | 91 (13.5) | 180 (12.3) | 1233 (19.6) |

| TNFi | 70 (8.9) | 83 (12.3) | 153 (10.5) | 1094 (17.4) |

| Non‐TNFi bDMARD | 24 (3.0) | 15 (2.2) | 39 (2.7) | 322 (5.1) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | ||||

| Never smoked | 618 (78.2) | 584 (86.6) | 1202 (82.1) | 3900 (61.9) |

| Smoker | 100 (12.7) | 50 (7.4) | 150 (10.2) | 1095 (17.4) |

| Ex‐smoker | 72 (9.1) | 40 (5.9) | 112 (7.7) | 1092 (17.3) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 60 (7.6) | 41 (6.1) | 101 (6.9) | 489 (7.8) |

| Hypertension | 189 (23.9) | 144 (21.4) | 333 (22.7) | 2204 (35.0) |

BID, twice daily; bDMARD, biologic DMARD; BMI, body mass index; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CRP, C‐reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic DMARD; DAS28‐4, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; DMARD, disease–modifying antirheumatic drug; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ‐DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire‐Disability Index; LTE, long‐term extension; MTX, methotrexate; P, Phase; RF, rheumatoid factor; SD, standard deviation; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

The average total daily dose (TDD) of tofacitinib was calculated: patients were assigned to the 5 mg BID group if the TDD was <15 mg/d and to the 10 mg BID group if it was ≥15 mg/d.

The P123LTE population (Asia‐Pacific) included patients from one Phase 1 study, four Phase 2 studies, six Phase 3 studies, and two LTE studies.

The global population (Asia‐Pacific and all other study locations) included patients from two Phase 1 studies, 10 Phase 2 studies, six Phase 3 studies, and two LTE studies.

The number of patients with baseline data available was variable across characteristics.

3.2. Efficacy

Efficacy data are reported for the 1022 patients in the P2/3 population, of whom 397 were randomized to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, 382 to tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, and 243 to placebo.

At month 3, greater response rates were observed for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily vs placebo, respectively, for ACR20 (69.2% [95% CI: 64.3, 73.9] and 77.9% [73.3, 82.1] vs 27.5% [21.7, 33.9]), ACR50 (36.9% [32.0, 42.0] and 44.4% [39.2, 49.7] vs 9.5% [6.0, 14.1]), and ACR70 (15.1% [11.7, 19.4] and 22.4% [18.1, 27.0] vs 2.7% [1.0, 5.8]) (Figure 1). ACR response rates were maintained through month 24 for patients who were randomized to receive tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily (Figure 1); greater response rates were observed with tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg twice daily. By month 9, patients who advanced to tofacitinib from placebo at month 3 or month 6 achieved similar ACR responses to those randomized to tofacitinib from baseline.

Figure 1.

American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response rates through Month 24. (A) ACR20, (B) ACR50, and (C) ACR70 response rates through to month 24 by treatment sequence (P2/3 population). ACR20/50/70, 20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology criteria; BID, twice daily; P, Phase; SE, standard error. Full analysis set, no imputation. The P2/3 population included patients from three Phase 2 studies and five Phase 3 studies. Patients randomized to placebo advanced to tofacitinib at month 3 or month 6; beyond month 6 all patients were receiving tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID

At baseline, mean DAS28‐4(ESR) scores were similar for patients randomized to receive tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily and placebo (6.4, 6.3, and 6.1, respectively). At month 3, lower mean DAS28‐4(ESR) scores were observed for patients who received tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily vs placebo (4.4 [95% CI: 4.3, 4.6] and 3.9 [3.8, 4.1] vs 5.6 [5.4, 5.8], respectively; Figure 2A). Observed reductions in DAS28‐4(ESR) scores were maintained through to month 24.

Figure 2.

Mean DAS28‐4(ESR) score and rates of DAS28‐4(ESR)‐defined and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)–defined remission and LDA through to month 24. (A) Mean DAS28‐4(ESR) score, (B) proportion of patients achieving DAS28‐4(ESR) remission (score ≤2.6), (C) proportion of patients achieving DAS28‐4(ESR) LDA (score ≤3.2), (D) proportion of patients achieving CDAI remission (score ≤2.8), and (E) proportion of patients achieving CDAI LDA (score ≤10) through to month 24 by treatment sequence (P2/3 population). BID, twice daily; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28‐4(ESR), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LDA, low disease activity; P, Phase; SE, standard error. Full analysis set, no imputation. The P2/3 population included patients from three Phase 2 studies and five Phase 3 studies. Patients randomized to placebo advanced to tofacitinib at month 3 or month 6; beyond month 6 all patients were receiving tofacitinib 5 mg or 10 mg BID

At month 3, DAS28‐4(ESR)‐defined remission and LDA were achieved by a greater proportion of patients who received tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (8.5% [95% CI: 5.7, 12.2] and 18.0% [14.0, 22.7], respectively) and 10 mg twice daily (18.5% [14.3, 23.4] and 31.7% [26.4, 37.3], respectively) vs placebo (2.6% [0.8, 5.9] and 6.7% [3.6, 11.2], respectively; Figure 2B,C). DAS28‐4(ESR) remission and LDA rates continued to improve through to month 24; higher rates were observed with tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg twice daily.

At month 3, CDAI‐defined remission and LDA were achieved by a greater proportion of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (6.1% [95% CI: 3.9, 9.1] and 34.1.% [95% CI: 29.3, 39.2], respectively) and 10 mg twice daily (12.3% [9.1, 16.2] and 45.5% [40.3, 50.9], respectively) vs placebo (0.5% [0.0, 2.5] and 13.1% [8.9, 18.2], respectively; Figure 2D,E). Rates of CDAI remission and LDA continued to improve to month 24; higher rates were observed with tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg twice daily.

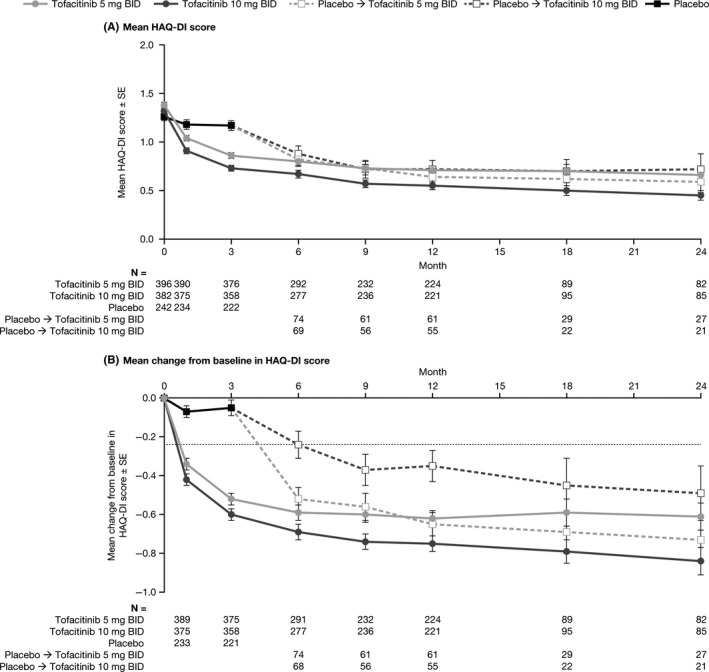

At baseline, mean HAQ‐DI scores were similar for patients randomized to receive tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily and placebo (1.4, 1.3, and 1.3, respectively). At month 3, mean HAQ‐DI scores were lower for patients who received tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily vs placebo (0.9 [95% CI: 0.8, 0.9] and 0.7 [0.7, 0.8] vs 1.2 [1.1, 1.3], respectively; Figure 3A) and changes from baseline in HAQ‐DI were greater (−0.5 [−0.6, −0.5] and −0.6 [−0.7, −0.5] vs −0.1 [−0.1, 0.0], respectively; Figure 3B). Mean improvements from baseline in HAQ‐DI surpassed the minimum clinically important difference (≥0.22 points) by month 3 for patients initially randomized to tofacitinib. Improvements from baseline in HAQ‐DI score were maintained to month 24, with greater improvements observed for tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg twice daily.

Figure 3.

Mean HAQ‐DI score and mean change from baseline in HAQ‐DI score through to month 24. (A) Mean HAQ‐DI score and (B) mean change from baseline in HAQ‐DI score through to month 24 by treatment sequence (P2/3 population). BID, twice daily; HAQ‐DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire‐Disability Index; P, Phase; SE, standard error. Full analysis set, no imputation. The dotted line in panel B indicates the minimum clinically important difference for HAQ‐DI (improvement ≥0.22). The P2/3 population includes patients from three Phase 2 studies and five Phase 3 studies. Patients randomized to placebo advanced to tofacitinib at month 3 or month 6; beyond month 6 all patients were receiving tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg BID

Mean PtGA and PGA scores were similar at baseline for patients randomized to receive tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily and placebo (PtGA: 62.0, 60.0, and 58.2, respectively; PGA: 61.8, 62.1, and 60.0, respectively). Lower mean PtGA and PGA scores were observed at month 3 for patients who received tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily vs placebo (PtGA: 35.1 [95% CI: 32.9, 37.3] and 29.6 [27.4, 31.8] vs 52.5 [49.3, 55.7], respectively; PGA: 29.7 [27.7, 31.6] and 25.4 [23.5, 27.2] vs 45.2 [42.2, 48.1], respectively). Patients who received tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily also experienced greater changes from baseline in PtGA and PGA scores vs placebo (PtGA: −27.0 [−29.7, −24.3] and −30.6 [−33.6, −27.7] vs −4.65 [−8.0, −1.3], respectively; PGA: −32.0 [−34.1, −29.9] and −37.0 [−39.4, −34.7] vs −14.0 [−17.0, −11.0], respectively). Observed reductions in PtGA and PGA scores were maintained through to month 24 (Figure S1 and Figure S2); generally, reductions were greater with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily than 5 mg twice daily.

3.3. Safety

Safety data are reported for 1464 patients from the Asia‐Pacific region in the P123LTE population. Across all tofacitinib doses, the mean treatment duration was 1191 days (39.1 months; range: 2–2802 days [0.1–92.1 months]) and included a total of 4773 patient‐years of tofacitinib exposure. AE types were generally similar up to month 3, from month 3 to month 6, and post‐month 6 (Table S1). Across all doses, the most common AEs, by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred term, were nasopharyngitis (EAER: up to month 3: 23.5; month 3 to month 6: 24.9; post‐month 6: 9.9), upper respiratory tract infection (EAER up to month 3: 17.8; month 3 to month 6: 13.1; post‐month 6: 5.3) and HZ (EAER: up to month 3: 7.7; month 3 to month 6: 7.9; post‐month 6: 4.8).

Over 92 months, SAEs occurred in 413 patients (IR per 100 patient‐years: 9.4 [95% CI: 8.5, 10.3]) and discontinuations due to AEs in 429 patients (IR: 9.1 [8.3, 10.1]). The SAE IR was numerically higher with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily vs 5 mg twice daily, although 95% CI overlapped between doses (Table 2). Overall, seven deaths were reported in patients receiving tofacitinib, or within 30 days of their last tofacitinib dose (IR: 0.1 [0.1, 0.3]). Table S2 lists cause and day of death and additional background information.

Table 2.

Incidence rates (patients with event/100 patient‐years) for AEs of special interest (P123LTE population)

| n (%) IR [95% CI] | Asia‐Pacific population | Global population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tofacitinib 5 mg BID N = 790 PY =2491 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg BID N = 674 PY = 2283 |

All tofacitinib doses N = 1464 PY = 4773 |

All tofacitinib doses N = 6301 PY = 21 199 |

|

| SAEs |

208 (26.3) 9.0 [7.9, 10.4] |

205 (30.4) 9.7 [8.4, 11.2] |

413 (28.2) 9.4 [8.5, 10.3] |

1766 (28.0) 9.4 [8.9, 9.8] |

| Discontinuations due to AEs |

232 (29.4) 9.5 [8.3, 10.8] |

197 (29.2) 8.8 [7.6, 10.1] |

429 (29.3) 9.1 [8.3, 10.1] |

1528 (24.3) 7.2 [6.9, 7.6] |

| Deaths[Link] |

3 (0.4) 0.1 [0.03, 0.4] |

4 (0.6) 0.2 [0.1, 0.5] |

7 (0.5) 0.1 [0.1, 0.3] |

107 (1.7) 0.5 [0.4, 0.6] |

| Serious infections[Link] |

84 (10.6) 3.4 [2.7, 4.2] |

90 (13.4) 4.0 [3.2, 4.9] |

174 (11.9) 3.7 [3.2, 4.3] |

554 (8.8) 2.6 [2.4, 2.9] |

| Herpes zoster (all cases) |

128 (16.2) 5.7 [4.8, 6.8] |

122 (18.1) 6.1 [5.1, 7.3] |

250 (17.1) 5.9 [5.2, 6.7] |

740 (11.7) 3.8 [3.5, 4.1] |

| Herpes zoster (serious)[Link] |

18 (2.3) 0.7 [0.4, 1.1] |

15 (2.2) 0.7 [0.4, 1.1] |

33 (2.3) 0.7 [0.5, 1.0] |

56 (0.9) 0.3 [0.2, 0.3] |

| Opportunistic infections excluding tuberculosis |

16 (2.0) 0.7 [0.4, 1.1] |

15 (2.2) 0.7 [0.4, 1.1] |

31 (2.1) 0.7 [0.4, 0.9] |

68 (1.1) 0.3 [0.3, 0.4] |

| Tuberculosis |

6 (0.8) 0.2 [0.1, 0.5] |

22 (3.3) 1.0 [0.6, 1.5] |

28 (1.9) 0.6 [0.4, 0.9] |

36 (0.6) 0.2 [0.1, 0.2] |

| Malignancy (excluding NMSC) |

21 (2.7) 0.8 [0.5, 1.3] |

19 (2.8) 0.8 [0.5, 1.3] |

40 (2.7) 0.8 [0.6, 1.1] |

179 (2.8) 0.8 [0.7, 1.0] |

| NMSC |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.1] |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.2] |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.1] |

117 (1.9) 0.6 [0.5, 0.7] |

| Breast cancer[Link] |

3 (0.4) 0.1 [0.03, 0.4] |

2 (0.3) 0.1 [0.01, 0.4] |

5 (0.4) 0.1 [0.04, 0.3] |

27 (0.5) 0.2 [0.1, 0.2] |

| Lung cancer |

4 (0.5) 0.2 [0.04, 0.4] |

2 (0.3) 0.1 [0.01, 0.3] |

6 (0.4) 0.1 [0.1, 0.3] |

32 (0.5) 0.2 [0.1, 0.2] |

| Gastric cancer |

3 (0.4) 0.1 [0.03, 0.4] |

2 (0.3) 0.1 [0.01, 0.3] |

5 (0.3) 0.1 [0.03, 0.2] |

5 (0.1) 0.02 [0.01, 0.1] |

| Lymphoma |

1 (0.1) 0.04 [0.0, 0.2] |

1 (0.2) 0.04 [0.0, 0.2] |

2 (0.1) 0.04 [0.0, 0.2] |

19 (0.3) 0.1 [0.1, 0.1] |

| MACEe |

6 (0.8) 0.3 [0.1, 0.6] |

10 (1.5) 0.4 [0.2, 0.8] |

16 (1.1) 0.3 [0.2, 0.6] |

84 (1.4) 0.4 [0.3, 0.5] |

| Gastrointestinal perforation |

1 (0.1) 0.04 [0.0, 0.2] |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.2] |

1 (0.1) 0.02 [0.0, 0.1] |

27 (0.4) 0.1 [0.1, 0.2] |

AE, adverse event; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; IR, incidence rate; LTE, long‐term extension; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; NMSC, non‐melanoma skin cancer; P, Phase; PY, patient‐years; SAE, serious adverse event.

The average total daily dose (TDD) of tofacitinib was calculated: patients were assigned to the 5 mg BID group if the TDD was <15 mg/d and to the 10 mg BID group if it was ≥15 mg/d.

The P123LTE population (Asia‐Pacific) included patients from one Phase 1 study, four Phase 2 studies, six Phase 3 studies, and two LTE studies.

The global population (Asia‐Pacific and all other study locations) included patients from two Phase 1 studies, 10 Phase 2 studies, six Phase 3 studies, and two LTE studies.

Within 30 days of last study drug dose.

Infection requiring hospitalization or parenteral antibiotic treatment.

Female patients only; PY of tofacitinib exposure for all tofacitinib doses was 4139 for the Asia‐Pacific population and 17 538 for the global population.

MACE were adjudicated from February 2009; PY of tofacitinib exposure for all tofacitinib doses was 4669 for the Asia‐Pacific population and 20 262 for the global population.

Serious infections were reported in 174 patients (IR: 3.7 [3.2, 4.3]). The most common serious infections were serious HZ (n = 32), pneumonia (n = 32), and tuberculosis (n = 24). In total, 250 cases of HZ (both serious and non‐serious) were reported (IR: 5.9 [5.2, 6.7]). Of these, most involved a single dermatome (n = 232; 92.8%), four cases involved two adjacent dermatomes, two were disseminated cases, and 12 were multidermatomal (non‐adjacent dermatomes or >2 adjacent dermatomes). Opportunistic infections (excluding tuberculosis) and tuberculosis were reported in 31 and 28 patients, respectively. Malignancies (excluding NMSC) were reported in 40 patients (IR: 0.8 [0.6, 1.1]) and included five cases of breast cancer, six cases of lung cancer, two cases of lymphoma, and five cases of gastric cancer. MACE were reported in 16 patients (IR: 0.3 [0.2, 0.6]). One gastrointestinal perforation event was reported. IRs were numerically higher for patients treated with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily vs 5 mg twice daily for serious infections and HZ (all cases); however, 95% CI overlapped between doses (Table 2). The tuberculosis IR was greater for patients treated with 10 mg twice daily (1.0 [0.6, 1.5]) vs 5 mg twice daily (0.2 [0.1, 0.5]).

Confirmed lymphopenia (lymphocyte count <0.5 × 103/mm3) was reported in 27 patients overall (IR: 0.6 [0.4, 0.8]) and confirmed decreases in hemoglobin (decrease ≥3 mg/dL or level ≤7 mg/dL) occurred in nine patients (IR: 0.2 [0.1, 0.4]); no cases of clinically significant neutropenia (neutrophil count <0.5 × 103/mm3) were reported (Table 3). ALT and AST increases >3 × the upper limit of normal were reported in 34 (IR: 0.7 [0.5, 1.0]) and 11 (IR: 0.2 [0.1, 0.4]) patients, respectively. No dose‐response was observed for changes in laboratory parameters (Table 3). Across all tofacitinib doses, initial mean increases from baseline in LDL‐c (16.6%), HDL‐c (19.9%), total cholesterol (16.7%), and creatine kinase (53.3 IU/L) were observed at month 3; levels were then generally stable over time, although fluctuations were observed at later time points (>60 months) for LDL‐c and HDL‐c when fewer patients remained in the analysis. Similar changes from baseline were observed with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily.

Table 3.

Incidence rates (patients with event/100 patient‐years) for confirmed changes in laboratory parameters (P123LTE population)

| n (%) IR [95% CI] | Asia‐Pacific population | Global population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tofacitinib 5 mg BID N = 790 PY = 2491 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg BID N = 674 PY = 2283 |

All tofacitinib doses N = 1464 PY = 4773 |

All tofacitinib doses N = 6301 PY = 21 199 |

|

| Lymphocyte count <0.5 × 103/mm3 |

12 (1.5) 0.5 [0.3, 0.9] |

15 (2.2) 0.7 [0.4, 1.1] |

27 (1.8) 0.6 [0.4, 0.8] |

72 (1.1) 0.3 [0.3, 0.4] |

| Neutrophil count <0.5 × 103/mm3 |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.2] |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.2] |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.1] |

0 (0.0) 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| Decrease in hemoglobin ≥3 g/dL or hemoglobin level ≤7 g/dL |

5 (0.6) 0.2 [0.1, 0.5] |

4 (0.6) 0.2 [0.1, 0.5] |

9 (0.6) 0.2 [0.1, 0.4] |

90 (1.4) 0.4 [0.3, 0.5] |

| ALT increase >3 × ULN |

18 (2.3) 0.7 [0.4, 1.2] |

16 (2.4) 0.7 [0.4, 1.2] |

34 (2.3) 0.7 [0.5, 1.0] |

141 (2.2) 0.7 [0.6, 0.8] |

| AST increase >3 × ULN |

6 (0.8) 0.2 [0.1, 0.5] |

5 (0.7) 0.2 [0.1, 0.5] |

11 (0.8) 0.2 [0.1, 0.4] |

58 (0.9) 0.3 [0.2, 0.4] |

| Serum creatinine increase ≥50% from baseline |

35 (4.4) 1.4 [1.0, 2.0] |

26 (3.9) 1.2 [0.8, 1.7] |

61 (4.2) 1.3 [1.0, 1.7] |

319 (5.1) 1.6 [1.4, 1.7] |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; LTE, long‐term extension; P, Phase; PY, patient‐years; ULN, upper limit of normal.

The average total daily dose (TDD) of tofacitinib was calculated: patients were assigned to the 5 mg BID group if the TDD was <15 mg/d and to the 10 mg BID group if it was ≥15 mg/d.

The P123LTE population (Asia‐Pacific) included patients from one Phase 1 study, four Phase 2 studies, six Phase 3 studies, and two LTE studies.

The global population (Asia‐Pacific and all other study locations) included patients from two Phase 1 studies, 10 Phase 2 studies, six Phase 3 studies, and two LTE studies.

4. DISCUSSION

This post‐hoc analysis of pooled data from Phase 1, Phase 2, Phase 3, and LTE studies in the tofacitinib clinical development program demonstrated the efficacy (P2/3 only) and safety of tofacitinib in patients with RA from the Asia‐Pacific region.

In Asia‐Pacific patients with prior inadequate response to DMARDs, tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily provided greater improvements in RA signs and symptoms and physical function vs placebo at month 3, with improvements sustained through 24 months. Improvements in efficacy endpoints in this pooled analysis were similar or even slightly higher than the range reported across the global Phase 3 studies up to 24 months.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 For example, ACR20 response rates (placebo‐adjusted) with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily were 41.7% and 50.4%, respectively, at month 3 in the P2/3 Asia‐Pacific population, vs 19.1%–35.5% and 25.7%–42.6%, respectively, at month 3 across global Phase 3 studies (data on file). These differences in efficacy between populations may be explained by differences in patient characteristics, such as the lower proportion of Asia‐Pacific patients who had previously received bDMARDs (12%) vs the global population (20%). Similarly, higher responses to several bDMARDs (including infliximab, etanercept, and tocilizumab) have been shown in Japanese vs Western patients with RA.29 To allow dose comparisons in a randomized study setting, efficacy data from the Asia‐Pacific sub‐population in the LTE studies were not included in this analysis, as the LTE studies had an open‐label design and dose adjustments were allowed. However, sustained efficacy of tofacitinib up to 96 months has been reported in the global population.14, 15, 16

Safety data have been reported up to 114 months in the global studies;14 however, the maximum exposure in patients from the Asia‐Pacific region in this analysis was 92 months. Safety data in the global population up to 92 months of exposure were therefore presented alongside the Asia‐Pacific population for context.

Increased risk of HZ has previously been identified in patients from Japan and Korea vs other countries,30 and this finding was confirmed in this analysis of patients from the Asia‐Pacific region. The higher HZ IR in patients from the Asia‐Pacific region (5.9 [5.2, 6.7]) vs the global population (3.8 [3.5, 4.1]) is consistent with previous analyses that identified Asian race as a risk factor for HZ in tofacitinib‐treated patients.30 This previous analysis, which included data pooled from 4789 patients across global Phase 2, Phase 3, and LTE studies, found that while HZ IRs were substantially higher in patients from Japan and Korea (9.2 [7.5, 11.4]) vs the global population, IRs in patients from China and Taiwan (4.6 [2.5, 8.2]) and Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines (2.2 [0.7, 6.8]) were more similar to the global population.30 Similarly, an increased risk of HZ in patients from Japan vs the global population has also been reported with the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib.31 The reported background incidence of HZ in the general population of Japan32 is similar to the global population,33, 34 but is higher in Japanese patients with RA.35 Higher background incidence of HZ in the general population has been reported in a study in Korea36 vs the global population.33, 34 A genome‐wide association study identified a single nucleotide polymorphism near IL‐17RB associated with a faster rate of HZ onset and which was more common in East Asian (~17%) vs Caucasian (<0.2%) populations, which may explain some of these observed differences.37 However, the reasons for these country‐specific differences in HZ incidence following tofacitinib treatment require further investigation. Other factors, such as the proportion of patients who were vaccinated against HZ prior to the studies, may play a role in the regional differences observed in the incidence of HZ.

The SAE IR for all tofacitinib doses in the Asia‐Pacific sub‐population (9.4 [95% CI: 8.5, 10.3]) was the same as that in the global population (9.4 [8.9, 9.8]), while the IR for discontinuations due to AEs was higher in Asia‐Pacific patients (9.1 [8.3, 10.1]) vs the global population (7.2 [6.9, 7.6]). IRs for malignancy events (excluding NMSC) in Asia‐Pacific patients were similar to those reported in the global population. Although all five reported gastric cancer events were in Asia‐Pacific patients, prevalence of gastric cancer is known to be higher in Asia than the rest of the world.38

The serious infections IR was higher in the Asia‐Pacific population (3.7 [3.2, 4.3]) vs the global population (2.6 [2.4, 2.9]). This difference may be explained partly by the higher proportion of Asia‐Pacific patients receiving concomitant corticosteroids vs the global tofacitinib population (72.1% vs 66.7%), as corticosteroid treatment has been identified as an independent risk factor for serious infections39, 40, 41 and HZ42 in tofacitinib‐treated patients. There are also differences in infection management between regions, and physicians in Asia may treat infections more aggressively and be more likely to recommend parenteral treatment or hospitalization vs other regions, resulting in these infections being considered serious. The difference in incidence of serious infection events between Asia‐Pacific and global patients may underlie the observed difference in incidence of discontinuations due to AEs, as ~40% of AEs leading to discontinuation were infections.

The tuberculosis IR reported in tofacitinib‐treated patients from the Asia‐Pacific region (0.6 [0.4, 0.9]) was higher than that in the global population (0.2 [0.1, 0.2]). However, a higher tuberculosis IR in the Asia‐Pacific region was expected, considering that among the eight Asia‐Pacific countries included in this analysis, all but one (Japan) are classified as high tuberculosis‐burden countries based on National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (>40 cases per 100 000 people per year).43, 44 Similar to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors,45 the tofacitinib prescribing information states that patients should be tested for latent tuberculosis prior to starting treatment and monitored for active tuberculosis during treatment.46

A limitation was that the LTE study population included in this post‐hoc analysis enrolled patients who had successfully completed qualifying Phase 1, 2, and 3 studies, a population in which tofacitinib was efficacious and well tolerated,14 and may not reflect the wider population with RA in clinical practice. Furthermore, this sub‐analysis was not designed for direct comparison of results between the Asia‐Pacific and global study populations, and the Asia‐Pacific population is smaller than the global study population; therefore, any comparisons should be treated with caution. In addition, no comparison was made between patients from the different Asia‐Pacific regions, who may show heterogeneity in responses to tofacitinib. Previous sub‐population analyses of LTE studies have been conducted in patients from Korea,20 Japan,16 and China,21 and showed consistent results with the data presented here; however, analyses have not previously been conducted on patient sub‐populations from the other five countries included in this analysis.

As tofacitinib is now approved for the treatment of RA in several countries worldwide, including those in the Asia‐Pacific region, an increasing number of studies reporting real‐world data for tofacitinib are being conducted,47, 48 and support the efficacy and safety observations from clinical studies. Regional analyses of real‐world data are of particular importance as they reflect the clinical treatment of patients, which may differ between regions, and provide larger study populations compared with clinical studies that are likely to enroll only relatively small numbers of patients from each region. Additional analyses based on real‐world data of tofacitinib treatment in patients from the Asia‐Pacific region will be of interest to confirm the results presented here based on clinical study data.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily provided improvement in RA signs and symptoms over 24 months in patients from the Asia‐Pacific region. While the frequency of AEs and SAEs in the Asia‐Pacific patient population over 92 months was generally consistent with that reported in global studies, higher rates of infection events, including serious infections, HZ and tuberculosis were reported.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

EBL is a consultant for Pfizer Inc, and received a research grant from Green Cross Co, Republic of Korea. YL has nothing to disclose. W‐CT has received speaking or consultant fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Janssen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Pfizer Inc and Roche. HY has received research grants from AbbVie, Astellas, Ayumi, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Kaken, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Nippon Shinyaku, Ono, Pfizer Inc, Takeda, Teijin, Torii and UCB; and has received lecturing or consulting fees from Astellas, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Nippon Kayaku, Pfizer Inc, Takeda, Teijin and YL Biologics. CC, KK, LJL, YL, NS, LW and H‐JY are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. YT has received consulting and speaking fees from Astellas, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi, UCB and YL Biologics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

EBL, CC, KK, H‐JY, LJL, LW, YL, and NS contributed to the study conception and design, and acquisition and analysis of data. All authors were involved in the interpretation of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, have given final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de‐identified participant data from Pfizer‐sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (a) for indications that have been approved in the USA and/or EU or (b) in programs that have been terminated (ie development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de‐identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Alice MacLachlan, PhD, of CMC CONNECT, a division of McCann Health Medical Communications Ltd, Glasgow, UK and funded by Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163: 461‐464).

Lee EB, Yamanaka H, Liu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients from the Asia‐Pacific region: Post‐hoc analyses of pooled clinical study data. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1094–1106. 10.1111/1756-185X.13516

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01484561 (registered December 2011), NCT01262118 (registered December 2010), NCT00147498 (retrospectively registered September 2005), NCT00413660 (registered December 2006), NCT00550446 (retrospectively registered October 2007), NCT00603512 (registered January 2008), NCT00687193 (registered May 2008), NCT00976599 (registered September 2009), NCT01059864 (registered February 2010), NCT01164579 (registered July 2010), NCT01359150 (registered May 2011), NCT02147587 (registered May 2014), NCT00814307 (registered December 2008), NCT00847613 (registered February 2009), NCT00856544 (registered March 2009), NCT00853385 (registered March 2009), NCT00960440 (registered August 2009), NCT01039688 (registered December 2009), NCT00413699 (registered December 2006), NCT00661661 (registered April 2008).

Funding information

The studies included in this analysis were funded by Pfizer Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1316‐1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kremer JM, Bloom BJ, Breedveld FC, et al. The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP‐690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):1895‐1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanaka Y, Suzuki M, Nakamura H, Toyoizumi S, Zwillich SH; Tofacitinib Study Investigators . Phase II study of tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) combined with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(8):1150‐1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleischmann R, Cutolo M, Genovese MC, et al. Phase IIb dose‐ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) or adalimumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):617‐629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kremer JM, Cohen S, Wilkinson BE, et al. A phase IIb dose‐ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) versus placebo in combination with background methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(4):970‐981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Nakamura H, Toyoizumi S, Zwillich S. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib as monotherapy in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a 12‐week, randomized, phase 2 study. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(4):514‐521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles‐Schoeman C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9865):451‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo‐controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):495‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kremer J, Li Z‐G, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(4):253‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(25):2377‐2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van der Heijde D, Tanaka Y, Fleischmann R, et al. Tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve‐month data from a twenty‐four‐month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(3):559‐570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):508‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Hall S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy, tofacitinib with methotrexate, and adalimumab with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ORAL Strategy): a phase 3b/4, double‐blind, head‐to‐head, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):457‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open‐label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(5):837‐852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: safety and efficacy in open‐label, long‐term extension studies over 9 years. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(Suppl 10):683‐684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamanaka H, Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, as monotherapy or with background methotrexate, in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an open‐label, long‐term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1094‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960‐977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lau CS, Chia F, Harrison A, et al. APLAR rheumatoid arthritis treatment recommendations. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(7):685‐713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee H, Chen C, Chapman D, Dasic G, Wang L, Llamado LJ. Safety, tolerability for tofacitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor in open‐label, long‐term extension up to 6.5 years, in Korean rheumatoid arthritis patients. Int J Rheum Dis 2016;19(Suppl 2):192 (abstract APL16‐1326).24612527 [Google Scholar]

- 21. An Y, Zhanguo L, Guiye L, Wang L, Wu Q, Wang L. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for the treatment of Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis in open‐label, long‐term extension study. Int J Rheum Dis 2016;19(Suppl 2):197 (abstract APL16‐1006). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kremer JM, Kivitz AJ, Simon‐Campos JA, et al. Evaluation of the effect of tofacitinib on measured glomerular filtration rate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomised controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McInnes IB, Kim H‐Y, Lee S‐H, et al. Open‐label tofacitinib and double‐blind atorvastatin in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):124‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyle DL, Soma K, Hodge J, et al. The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib suppresses synovial JAK1‐STAT signalling in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1311‐1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Charles‐Schoeman C, Fleischmann R, Davignon J, et al. Potential mechanisms leading to the abnormal lipid profile in patients with rheumatoid arthritis versus healthy volunteers and reversal by tofacitinib. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(3):616‐625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Conaghan PG, Østergaard M, Bowes MA, et al. Comparing the effects of tofacitinib, methotrexate and the combination, on bone marrow oedema, synovitis and bone erosion in methotrexate‐naive, early active rheumatoid arthritis: results of an exploratory randomised MRI study incorporating semiquantitative and quantitative techniques. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1024‐1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Winthrop KL, Silverfield J, Racewicz A, et al. The effect of tofacitinib on pneumococcal and influenza vaccine responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(4):687‐695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winthrop KL, Wouters AG, Choy EH, et al. The safety and immunogenicity of live zoster vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis before starting tofacitinib: a randomized Phase II trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(10):1969‐1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takeuchi T, Kameda H. The Japanese experience with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(11):644‐652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winthrop KL, Yamanaka H, Valdez H, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(Suppl 10):2675‐2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tanaka Y, Atsumi T, Amano K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: subgroup analyses of four multinational phase 3 randomized trials. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;14:1094‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toyama N, Shiraki K. Epidemiology of herpes zoster and its relationship to varicella in Japan: a 10‐year survey of 48,388 herpes zoster cases in Miyazaki prefecture. J Med Virol. 2009;81(12):2053‐2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yawn BP, Gilden D. The global epidemiology of herpes zoster. Neurology. 2013;81(10):928‐930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e004833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakajima A, Urano W, Inoue E, Taniguchi A, Momohara S, Yamanaka H. Incidence of herpes zoster in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis from 2005 to 2010. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(4):558‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim YJ, Lee CN, Lim CY, Jeon WS, Park YM. Population‐based study of the epidemiology of herpes zoster in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(12):1706‐1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bing N, Zhou H, Zhang B, et al. Genome‐wide trans‐ancestry meta‐analysis of herpes zoster in RA and Pso patients treated with tofacitinib. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(Suppl 10):799‐800 (abstract 566). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah JA. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(16):4483‐4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Strangfeld A, Eveslage M, Schneider M, et al. Treatment benefit or survival of the fittest: what drives the time‐dependent decrease in serious infection rates under TNF inhibition and what does this imply for the individual patient? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1914‐1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grijalva CG, Kaltenbach L, Arbogast PG, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. Initiation of rheumatoid arthritis treatments and the risk of serious infections. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(1):82‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, et al. Long‐term safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis up to 8.5 years: integrated analysis of data from the global clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(7):1253‐1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winthrop KL, Curtis JR, Lindsey S, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib: clinical outcomes and the risk of concomitant therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(10):1960‐1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis report 2017. 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed March 14, 2018.

- 44. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Tuberculosis. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng33/resources/tuberculosis-pdf-1837390683589. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- 45. Chen YH, de Carvalho HM, Kalyoncu U, et al. Tuberculosis and viral hepatitis infection in Eastern Europe, Asia, and Latin America: impact of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha inhibitors in clinical practice. Biologics. 2018;12:1094‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pfizer Inc . XELJANZ prescribing information. 2018. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?xml:id=959. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- 47. Kavanaugh AF, Geier J, Bingham C III, et al. Real world results from a post‐approval safety surveillance of tofacitinib (Xeljanz): over 3 year results from an ongoing US‐based rheumatoid arthritis registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10):3504‐3506. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mimori T, Harigai M, Atsumi T, et al. Post‐marketing surveillance of tofacitinib in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an interim report of safety data. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(Suppl 10):531‐532. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de‐identified participant data from Pfizer‐sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (a) for indications that have been approved in the USA and/or EU or (b) in programs that have been terminated (ie development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de‐identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.