Abstract

All‐trans‐retinoic acid (at RA) downregulates cytochrome P450 (CYP)2D6 in several model systems. The aim of this study was to determine whether all active retinoids downregulate CYP2D6 and whether in vitro downregulation translates to in vivo drug–drug interactions (DDIs). The retinoids at RA, 13cis RA, and 4‐oxo‐13cis RA all decreased CYP2D6 mRNA in human hepatocytes in a concentration‐dependent manner. The in vitro data predicted ~ 50% decrease in CYP2D6 activity in humans after dosing with 13cis RA. However, the geometric mean area under plasma concentration‐time curve (AUC) ratio for dextromethorphan between treatment and control was 0.822, indicating a weak induction of dextromethorphan clearance following 13cis RA treatment. Similarly, in mice treatment with 4‐oxo‐13cis RA–induced mRNA expression of multiple mouse Cyp2d genes. In comparison, a weak induction of CYP3A4 in human hepatocytes translated to a weak in vivo induction of CYP3A4. These data suggest that in vitro CYP downregulation may not translate to in vivo DDIs, and better understanding of the mechanisms of CYP downregulation is needed.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ Downregulation of cytochrome P450 (CYP) mRNA is commonly observed during the conduct of CYP induction studies in human hepatocytes, but the importance of these in vitro findings to in vivo drug–drug interaction (DDI) prediction is unclear.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ This study aimed to determine whether in vitro CYP downregulation translates to a clinical DDI using 13cis RA and its metabolites all‐trans‐retinoic acid (at RA), and 4‐oxo‐13cis RA as model compounds.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

☑ This study showed that CYP2D6 downregulation observed in human hepatocytes by 13cis RA and its metabolites did not translate to decreased clinical CYP2D6 activity in vivo even when distinct retinoid pharmacological effects were observed in all the volunteers.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

☑ Clinical DDIs cannot be reliably predicted from observations of CYP downregulation in vitro. Further studies are needed to characterize mechanisms of CYP downregulation in vitro and how these mechanisms translate to in vivo.

Drug–drug interaction (DDI) screening is an obligate part of drug‐development programs, and methods to predict potential DDIs involving inhibition or induction of enzymes and transporters are well developed.1, 2, 3 Guidance from the European Medicines Agency recommends investigation of possible DDIs resulting from transcriptional downregulation of enzymes in hepatocytes, but the in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) of cytochrome P450 (CYP) downregulation has not been established. The clinical significance of CYP downregulation was recently demonstrated in the development of obeticholic acid.4 In vitro evaluation in human hepatocytes showed downregulation of CYP1A2 mRNA, and in vivo a 42% increase in plasma area under concentration‐time curve (AUC) of caffeine was observed after dosing with obeticholic acid.4 The Induction Working Group of the IQ Consortium recently reported that mRNA downregulation is relatively frequently observed in hepatocyte studies, (16 of 17 companies surveyed had observed downregulation in routine induction studies), and in cases when downregulation was observed, the maximal decrease was commonly > 50%.5 However, the clinical translation of these findings is not known.

All‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA), the active metabolite of vitamin A, has been shown to downregulate the expression of CYP2D6 in vitro in cell models and in vivo in mice,6, 7, 8, 9 and decreased atRA‐mediated suppression of CYP2D6 transcription has been proposed to regulate CYP2D6 induction during pregnancy.6 The proposed mechanism is via atRA‐mediated induction of the transcriptional corepressor small heterodimer partner (SHP), which suppresses hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α‐mediated transcription of CYP2D6.6 However, whether CYP2D6 downregulation by retinoids occurs in vivo in humans is unknown. As atRA and its metabolites are not inhibitors of CYP2D6, they present an intriguing opportunity to study DDIs resulting solely from transcriptional downregulation. The isomer of atRA, 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (13cisRA), is an attractive model compound to elucidate the translation of CYP downregulation, as 13cisRA has a much longer half‐life (~ 20 hours) than atRA (~ 1 hour) resulting in little fluctuation in precipitant concentrations. In humans, 13cisRA isomerizes to atRA10, 11 and is metabolized to 4‐oxo‐13cisRA.12, 13 Therefore, the DDIs observed after treatment with 13cisRA may be precipitated by 13cisRA, atRA, 4‐oxo‐13cisRA, or a combination of the three.

The aim of this study was to characterize the effects of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on the expression of CYP2D6 in human hepatocytes and to determine whether the in vitro findings translate to predictable clinical DDIs. Due to prior reports of atRA being an inducer of CYP3A4 in vitro,14, 15 CYP3A4 induction was also evaluated.

Methods

Hepatocyte culture and assessment of CYP mRNA and activity

Cryopreserved human hepatocytes were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), (Hu1558, donor 1: 84‐year‐old white man and Hu1765, donor 2: 37‐year‐old white woman) and BioreaclamationIVT (Baltimore, MD) (FOS, donor 3: 34‐year‐old Arabic man). All donors were CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers. All experiments were conducted in triplicate unless otherwise noted. In all experiments, cell viability was assessed using the lactate dehydrogenase assay, as described previously,16 and cell morphology was monitored with the IncuCyte Zoom System from Essen BioScience (Ann Arbor, MI). The cells were plated and cultured and mRNA, activity, and retinoids analyzed, as described in Supplementary Methods . Twenty‐four hours after plating, cells were treated with rifampin (0.1, 1, 10, and 25 μM), GW4064 (0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM), 13cisRA, atRA, 4‐oxo‐13cisRA (0.005, 0.01, 0.04, 0.12, 0.37, 1.11, 3.33, 10, and 30 μM), or vehicle control (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide). Plates were incubated for 2 or 48 hours (replaced with fresh dosing medium after 24 hours) at 37°C in 5% CO2 prior to assessment of SHP mRNA (2 hours) and CYP mRNA and activity (48 hours). Maximum responses in SHP mRNA occurred at 1–2 hours of treatment and, therefore, changes in SHP mRNA were assessed after 2 hours and changes in CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 were measured at 48 hours. To determine retinoid concentrations in media at 2 and 48 hours, 25 μL of media were transferred to a 96‐well plate, quenched with 50 μL of acetonitrile, and stored at −80°C until analysis by liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry, as described in Supplementary Methods . The average retinoid concentrations measured between 2 and 48 hours at each treatment were used for concentration‐response data analysis.

Simulation of in vitro CYP2D6 mRNA and protein degradation

To explore the difference in the time‐course of change in CYP2D6 mRNA and activity (as a surrogate for CYP2D6 protein levels), the changes in CYP2D6 mRNA and activity as a function of time observed in donor 1 after treatment with 1 μM atRA for 1, 2, 24, and 48 hours were analyzed. A model was constructed in MATLAB and SimBiology Toolbox Release 2018b (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) to simulate the decline of CYP2D6 mRNA and protein with differing inhibition of mRNA synthesis (100, 75, 50, and 25% inhibition). The rate of mRNA synthesis was assumed to be zero‐order and set at 0.04 pmol/hour as the input for the mRNA species. The first‐order rate constant for mRNA degradation (k = 0.04 hour−1) was set as the input into the protein species, and the first‐order degradation rate constant for CYP2D6 (k = 0.015 hour−1) was applied to the protein species (see Supplementary Methods for calculation of rate constants). The simulation was run until all species reached steady state, then the rate of mRNA synthesis was decreased by 25, 50, 75, or 100%, and the decline in mRNA or protein species as a function of time was followed.

Prediction of DDIs

For DDI prediction, the unbound fraction of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA in human plasma and hepatocyte media was determined by rapid equilibrium dialysis, as described in Supplementary Methods , and the fraction unbound (f u) for each retinoid was calculated. To quantify the concentration‐effect relationship of 13cisRA, atRA, or 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on CYP2D6 in human hepatocytes, estimates of the minimum fraction of expression or activity remaining relative to control (minimum effect (Emin)) and the retinoid concentration at 50% of the maximum effect (EC50) were determined by fitting the observed concentration‐effect data with three‐parameter nonlinear regression (Eq. (1))

| (1) |

in GraphPad Prism version 5.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The retinoid concentrations used were corrected for retinoid depletion as described above. The Emin and EC50 values are presented as the mean (90% confidence interval) for each donor. For use in predictions, unbound EC50 was calculated as f u,media × EC50.

The change in CYP2D6 expression in vivo following 13cisRA dosing was predicted based on the magnitude of CYP2D6 mRNA downregulation in human hepatocytes and average unbound concentrations (f u,plasma × average plasma concentration (Cavg)) of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA. For predictions, the average steady‐state plasma concentrations measured previously by us17 were used. The overall effect of the three compounds on CYP expression in vivo was predicted assuming that all three precipitants (13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA) bind to the same receptor to result in altered CYP expression via a competitive mechanism, as described previously.18 The prediction for the change in exposure of the sensitive CYP2D6 probe substrate dextromethorphan following dosing of 13cisRA to steady state was performed as previously described19 with an adaptation to account for the presence of m number of retinoids k each competing for binding to the receptor of interest:

| (2) |

AUC is the area under plasma concentration‐time curve, Cl is clearance, and f m is the fraction of substrate metabolized by the CYP of interest. For dextromethorphan, the f m by CYP2D6 in CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers was set to 0.98.20

Clinical study protocol

This study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board, and signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation in any study activities. The study was designed to have 80% power to detect a 50% change in dextromethorphan exposure with an α of 0.05. Due to teratogenicity of retinoids, only healthy male volunteers were enrolled in the study. The mean (± SD) age of the eight study subjects was 33 ± 10 years old, with height of 177 ± 7.53 cm, and weight of 79.1 ± 11.0 kg. Five subjects were white (four non‐Hispanic and one Hispanic) and three Asian. All subjects had normal hepatic and renal function and no history of allergy to study medications. Tobacco users or subjects with a pregnant partner were excluded from the study. Subjects agreed to abstain from over‐the‐counter and prescription medications and dietary supplements for the duration of the study. Subjects were administered a Patients Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) questionnaire at the beginning and end of the study to monitor for symptoms of depression, and no subject with a history of severe mental health problems was enrolled in the study. Subjects were genotyped for CYP2D6,21 and subjects with a CYP2D6 copy number other than 2 or CYP2D6*3 or CYP2D6*4 single‐nucleotide polymorphisms were not enrolled in the study.

On study day 1, subjects were administered a 30 mg dose of dextromethorphan and blood samples were collected prior to and 30 minutes and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 hours after drug administration. Urine was collected from 0–8 and 8–24 hours. On study day 2, subjects were given 13cisRA to be taken as 40 mg b.i.d. with food for 13 days (study days 2–14). The 13cisRA capsules were purchased (as Isotretinoin) by the University of Washington Investigational Pharmacy, which dispensed all study medications. On study day 15, subjects returned to the clinic and had a blood draw taken before administration of another 30 mg dose of dextromethorphan and a final 40 mg dose of 13cisRA. Blood samples were collected prior to and 30 minutes, and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 hours after drug administration. Urine was collected from 0–8 and 8–24 hours. Blood samples were collected in foil‐wrapped serum separator tubes, allowed to clot for a minimum of 30 minutes, and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 minutes. Serum was collected for storage in −80°C. Serum sample handling was conducted under yellow light to protect light‐sensitive retinoids from degradation. The 13cisRA and its metabolites atRA and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA were measured in all serum samples, dextromethorphan and its metabolites in all serum and urine samples, and cortisol and 6β‐hydroxycortisol in all serum and urine samples using validated liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry methods described in Supplementary Methods .

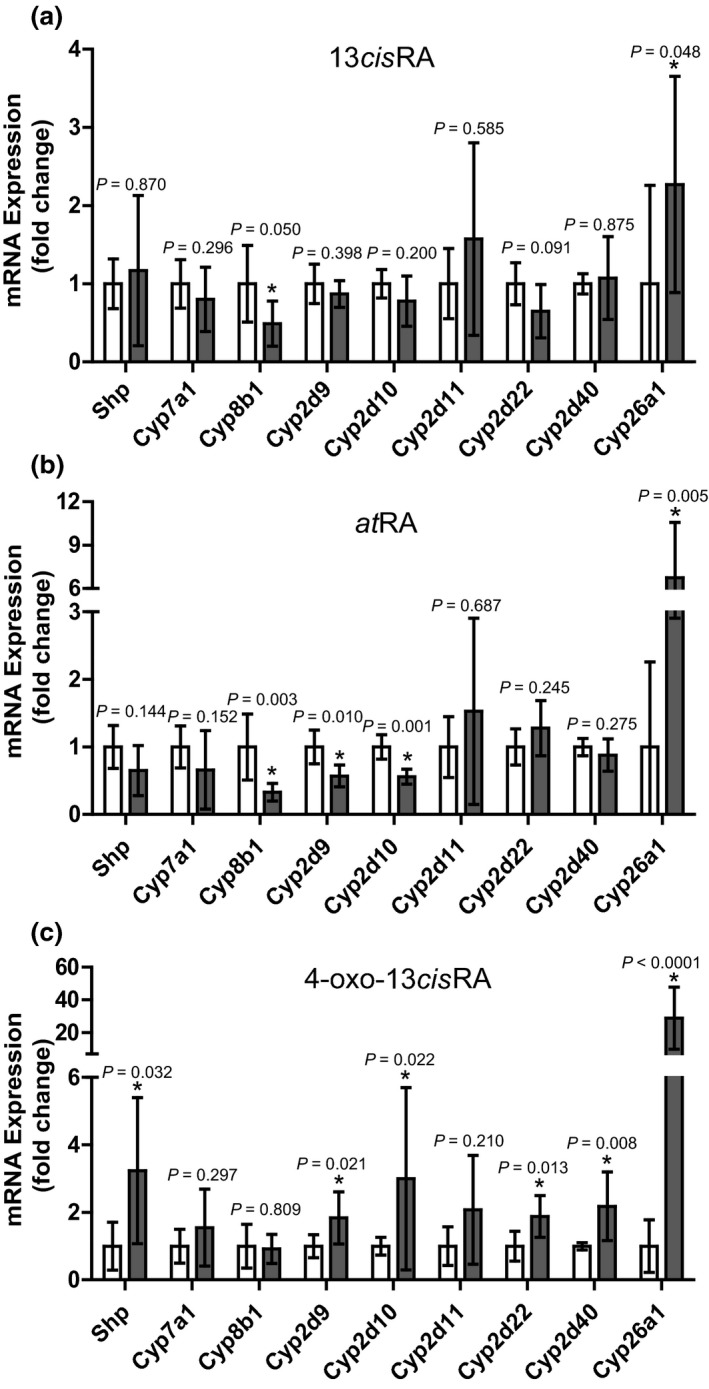

Determination of regulation of mouse CYP2D enzymes by retinoids

Experiments in mice were approved by the Washington State University Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult (~90 days old) male C57BL/6X129 mice were housed in a temperature‐controlled and humidity‐controlled environment, and food and water were available ad libitum. In two separate studies, mice were treated once daily for 3 days with i.p. injection of 5 mg/kg 13cisRA (n = 6), 5 mg/kg atRA (n = 6) or vehicle (10% dimethyl sulfoxide with 90% sesame oil; n = 5), or with 5 mg/kg 4‐oxo‐13cisRA (n = 6) or vehicle control (n = 6) i.p. On the evening of the third day, mice were fasted overnight (12 hours), and then food was reintroduced in the morning of the fourth day, and a final dose of retinoid or vehicle was administered. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation 4 hours following the last dose, and livers were collected for mRNA analysis. All samples were collected in a light‐protected environment and stored at −80°C until use. Changes in mRNA expression were analyzed by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) for Shp, Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, Cyp2d9, Cyp2d10, Cyp2d11, Cyp2d22, Cyp2d40, Cyp26a1, and Gapdh, as described in Supplemental Materials .

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using standard noncompartmental analysis in Phoenix WinNonlin v6.3 (Pharsight, St. Louis, MO), as described in Supplementary Methods . The formation clearance (Clf) of dextrorphan, 3‐methoxymorphinan, and 6β‐hydroxycortisol were each determined by dividing the sum of the molar equivalents of each compound and its downstream metabolites recovered in urine by the plasma AUC of each compound's respective parent, as described in Supplementary Methods . Statistical analyses were performed in Prism version 5.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The geometric mean and percentage of coefficient of variation (%CV) are reported for all pharmacokinetic parameters. A D'Agostino‐Pearson omnibus normality test was used to determine whether pharmacokinetic parameters had Gaussian distributions, and a Grubbs’ test was used to identify any outliers in the data. Differences in pharmacokinetic parameters on study day 15 compared with study day 1 were assessed by comparing the geometric mean ratio (GMR) and the 90% confidence interval to bioequivalence bounds of 0.8–1.25 according to US Food and Drug Administration guidance on DDI studies.2 Differences in mRNA levels between vehicle control and retinoid‐treated mice were assessed on log‐transformed qRT‐PCR data by analysis of variance for the first study dosing 13cisRA, atRA, or vehicle control or by t‐tests for the second study dosing 4‐oxo‐13cisRA and vehicle control. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

CYP2D6 and SHP regulation by retinoids in human hepatocytes

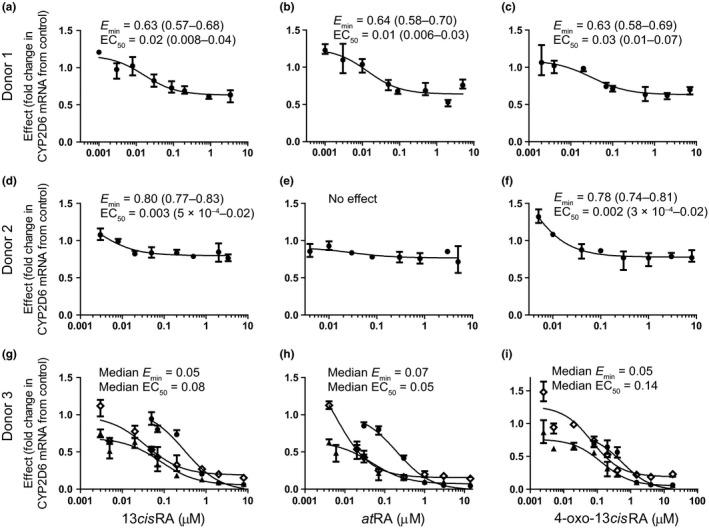

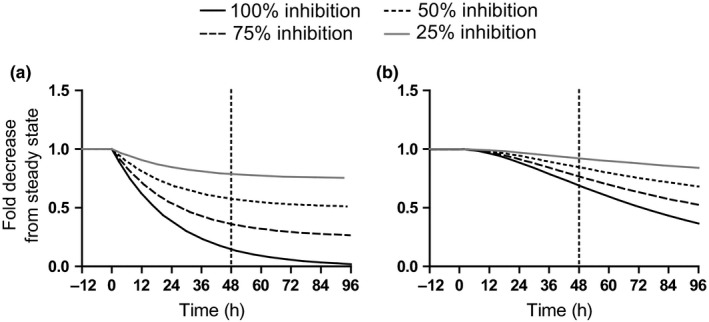

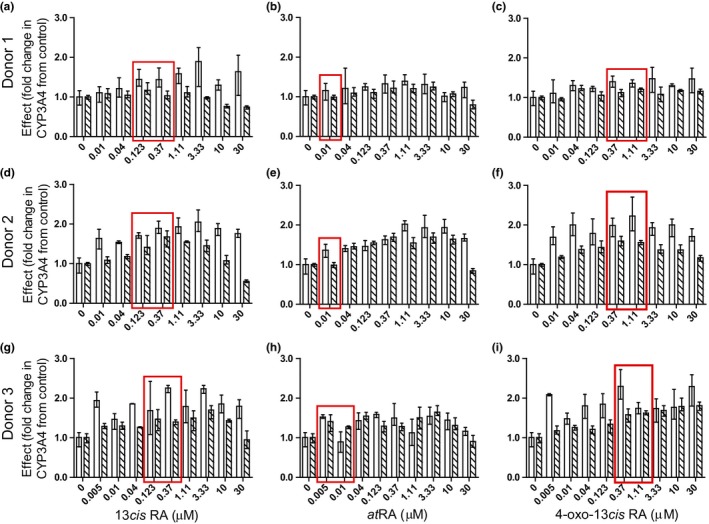

In retinoid‐treated hepatocytes, no cytotoxicity was observed at concentrations up to 100 μM, as determined by both assessment of morphology and lactate dehydrogenase leakage. Concentration‐dependent decreases in CYP2D6 mRNA were observed in all three donors treated with 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA, but there was large interindividual variability between the three donors (Figure 1 ). The Emin ranged from almost complete downregulation (95% decrease) to modest impact (20% decrease). SHP mRNA was induced in a dose‐dependent manner up to threefold by all three retinoids (Figure S1 ), and the SHP induction did not correlate with the magnitude of CYP2D6 mRNA suppression. The changes in CYP2D6 activity were concentration‐dependent but variable between donors with one donor having a 1.5‐fold increase and another an ~ 40% decrease. These changes did not directly correlate with changes in mRNA (Figure S2 ). The possible reasons for the discrepancy between changes in the CYP2D6 mRNA and activity in vitro were addressed via simulation (see Methods). The simulation suggests a substantial time lag for changes in CYP2D6 protein expression due to the long half‐life of CYP2D6 protein (Figure 2 ) and predicts discrepancy between mRNA and protein results. In contrast to the CYP2D6 suppression findings, retinoid treatment–induced CYP3A4 approximately twofold in two donors (Figure 3 and Figure S3 ). Increases in CYP3A4 activity were concentration‐dependent, and CYP3A4 induction was likely pregnane X receptor (PXR)‐mediated as all three retinoids were found to activate PXR in a reporter gene assay (Figure S4 ).

Figure 1.

Dose‐dependent downregulation of CYP2D6 mRNA by all‐trans‐retinoic acid (at RA), 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (13cis RA), and 4‐oxo‐13cis RA in three human hepatocyte donors. Panels (a,b,c) show donor 1, panels (d,e,f) show donor 2, and panels (g,h,i) show donor 3. The treatments shown are 13cis RA in panels a, d, and g, at RA in panels b, e, and h, and 4‐oxo‐13cis RA in panels c, f and i. The data are presented as mean and range of independent mRNA measurements (n = 3) in comparison to vehicle control. For donor 3, three separate experiments done on independent days are also shown. The minimum effect (Emin) and half‐maximal effective concentration (EC50; μM) shown were fit as described in the methods and are presented as mean and 90% confidence interval for donor 1 and donor 2. For donor 3, the median values from three replicate experiments are shown and the Emin and EC50 for each replicate experiment are provided in Table S1 . Inconsistent changes in CYP2D6 mRNA were observed in response to the small heterodimer partner inducer control, GW4064, at 1 μM (average 1.0‐fold, 1.2‐fold, and 0.3‐fold change in donors 1, 2, and 3, respectively).

Figure 2.

Simulations of the predicted time course of CYP2D6 mRNA (a) and protein (b) in human hepatocytes assuming a zero‐order mRNA synthesis rate of 0.04 pmol/hour and mRNA and protein elimination rate constants of 0.04 hour−1 and 0.015 hour−1, respectively. Simulations were conducted as described in the Methods section with 100% (solid black line), 75% (dashed line), 50% (dotted line), or 25% (solid gray line) inhibition of mRNA synthesis rate.

Figure 3.

The effects of 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (13cis RA), all‐trans‐retinoic acid (at RA), and 4‐oxo‐13cis RA on CYP3A4 mRNA and activity. Data for CYP3A4 mRNA (white bars) and activity (hashed bars) in donor 1 (a,b,c), donor 2 (d,e,f), and one replicate experiment in donor 3 (g,h,i) hepatocytes are presented as mean and range of the measured effect (n = 3 replicates per donor). The data from other two replicate experiments in donor 3 are shown in Figure S3 . The control rifampicin (25 μM) increased CYP3A4 mRNA by an average 38‐fold, 17‐fold, and 176‐fold and CYP3A4 activity by an average 3.0‐fold, 2.8‐fold, and 16‐fold in donors 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The concentrations listed on the x‐axis are the nominal concentrations added to the hepatocytes. The red boxes indicate the nominal concentrations that mimic clinically relevant circulating unbound concentrations.

The effects of each retinoid on the target genes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 were similar within a donor but had considerable between donor variability. To explore potential reasons for the donor‐to‐donor differences, the retinoid concentrations and the responsiveness of each donor to retinoids based on changes in two retinoic acid receptor (RAR) target genes, CYP26A1, and RARβ were measured. Significant depletion of the retinoids was observed in all donors (Figure S5 ), and the resulting concentration was similar between donors. The calculated retinoid average concentration (Cavg) was 7–23%, 11–50%, and 17–77% of nominal in donors 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Despite the similar retinoid concentrations, the three donors responded very differently to retinoid treatments. RARβ induction varied from 2‐fold to 7‐fold (donor 2) to 20‐fold to 40‐fold (donor 3) (Figure S6 ). CYP26A1 was robustly expressed in vehicle‐treated cells from donor 2 (cycle threshold (CT) of ~ 31) and induced about 60‐fold to 100‐fold. In comparison, in donor 3, the induction of CYP26A1 was much greater (1,000‐fold to 10,000‐fold) based on induction from undetectable (CT 38–40) to robust expression (CT 22–25) after treatment with 13cisRA, atRA, or 4‐oxo‐13cisRA.

Prediction of CYP2D6 downregulation and clinical DDIs

In vivo DDIs following treatment with 13cisRA were quantitatively predicted using Eq. (2), the in vitro hepatocyte data, and known circulating concentrations of the retinoids. The protein binding of the retinoids in hepatocyte media and in plasma and their average concentration during hepatocyte treatments were measured and used to determine unbound EC50 values for CYP2D6 mRNA downregulation. All the retinoids were extensively bound in the media and in plasma (Table 1 ). Using reported average plasma concentrations of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA after treatment with 13cisRA,17 the decrease in CYP2D6 expression following 13cisRA treatment was predicted based on each retinoid exposure alone and in combination (Table 1 ). An up to 77% decrease in CYP2D6 expression was predicted after 13cisRA dosing. Although 13cisRA alone was predicted to decrease CYP2D6 expression by 22% and atRA was not predicted to have any impact on CYP2D6 expression, exposure to 4‐oxo‐13cisRA as a 13cisRA metabolite was predicted to decrease CYP2D6 expression by 35–77%. Overall the 4‐oxo‐13cisRA metabolite was predicted to be the main in vivo precipitant of a predicted DDI. A 1.5‐fold to 4.0‐fold increase in dextromethorphan AUC was predicted based on the combined effect of all retinoids on CYP2D6 expression in hepatocytes. In contrast, following treatment at clinically relevant concentrations of 13cisRA (0.123–0.37 μM nominal) and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA (0.37–1.11 μM nominal), an increase in CYP3A4 activity was observed in hepatocytes (Figure 3 ) suggesting that 13cisRA is an in vivo CYP3A4 inducer. However, the wide confidence interval of the dose–response curves prevented quantitative predictions of CYP3A4 induction in vivo.

Table 1.

Plasma and media unbound fractions for the studied retinoids, in vitro EC50,u values, and predicted magnitude of in vivo change in CYP2D6 based on clinical 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA exposures

| End point | Precipitant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13cisRA | atRA | 4‐oxo‐13cisRA | Combined parent and metabolitesa | |

| f u,plasma b | 0.0004 (0.0001) | 0.0002 (5 × 10−5) | 0.012 (0.004) | |

| f u,media b | 0.011 (0) | 0.027 (0.008) | 0.121 (0.013) | |

| Cavg c (μM) | 0.69 | 0.01 | 5.4 | |

| Donor 1 d | ||||

| Emin | 0.63 (0.57–0.68) | 0.64 (0.58–0.70) | 0.63 (0.58–0.69) | |

| EC50,u (nM) | 0.18 (0.09–0.44) | 0.37 (0.16–0.81) | 3.8 (1.2–8.5) | |

| Predicted % CYP2D6 remaining | 0.78 | 1.0 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Donor 3 e | ||||

| Emin | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | |

| EC50,u (nM) | 0.91 | 1.3 | 17 | |

| Predicted % CYP2D6 remaining | 0.78 | 1.0 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

Donor 2 was excluded from quantitative predictions due to the wide confidence intervals of the determined EC50 values of retinoids on CYP2D6 mRNA in this donor (Figure 1 ).

atRA, all‐trans‐RA; Cavg, average concentration; CYP, cytochrome P450; EC50,u, unbound half‐maximal effective concentration; Emin, minimum concentration; fu,plasma, fraction unbound in plasma; fu,media, fraction unbound in media; NA, not applicable; RA, retinoic acid.

aThe combined effect of 13cisRA and its metabolites on CYP2D6 expression in vivo was predicted using Eq. (2). bBinding experiments were conducted in triplicate and data are presented as mean (SD). cCavg following administration of 20 mg b.i.d. 13cisRA reported in Amory et al.17 dThe concentration‐dependent effects of retinoids in donor 1 hepatocytes are presented as mean (90% confidence interval). eThe concentration‐dependent effects of retinoids in donor 3 hepatocytes were assessed in three replicate experiments, and the median value from the three experiments is reported.

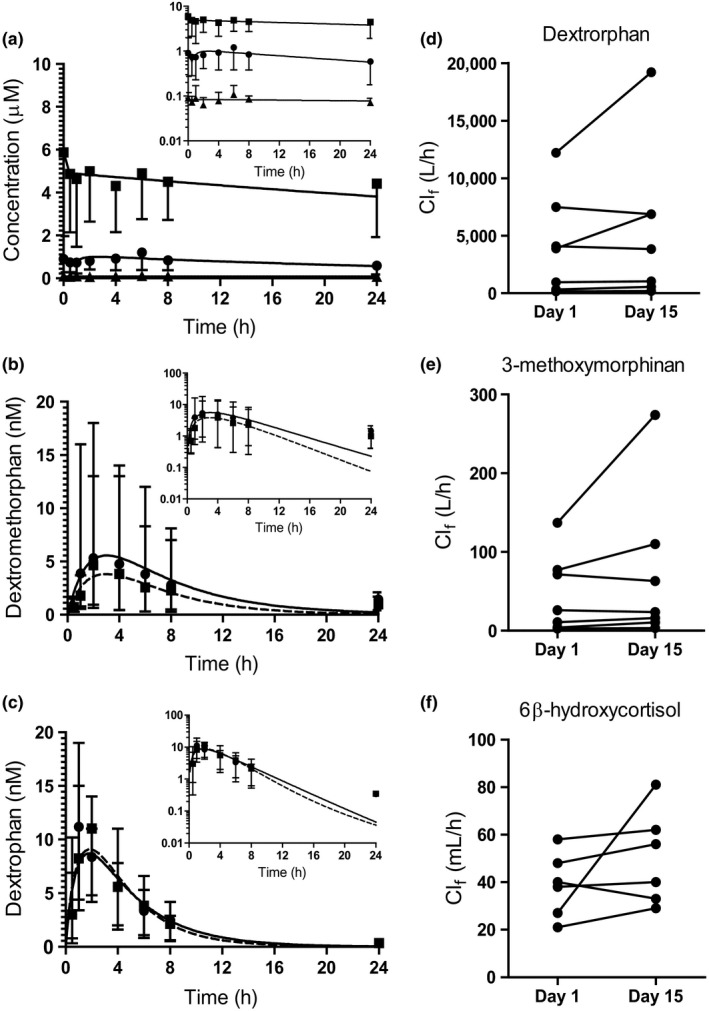

Clinical study of 13cisRA–CYP2D6 interaction

To test whether 13cisRA results in a decrease in CYP2D6 activity in the clinic, a DDI study was conducted using dextromethorphan as a probe. Compliance with 13cisRA dosing was 95% on average determined by self‐reported drug logs and counts of returned 13cisRA capsules. All subjects complained of anticipated adverse events related to 13cisRA dosing, including chapped lips and dry skin around the mouth, confirming RAR engagement in target tissues. The mean (%CV) steady‐state concentration (Cavg,ss) values for 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA in the study subjects were 0.88 μM (46%), 0.069 μM (22%), and 4.2 μM (59%), respectively (Figure 4 ). These concentrations were in close agreement with the concentrations measured in previous studies17 and used in the DDI predictions. No increase in dextromethorphan or dextrorphan area under the concentration‐time curve from zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) was observed after retinoid treatment in comparison with control (Figure 4 and Table 2 ). In contrast, the 90% confidence interval of the GMR for dextromethorphan maximum concentration (Cmax) and AUC0–∞ showed a decrease of dextromethorphan exposure following 13cisRA dosing (Table 2 ). The urinary dextrorphan to dextromethorphan ratio and the dextrorphan/dextromethorphan AUC ratio increased after 13cisRA treatment (GMR 1.25 treatment/control), and the mean dextrorphan formation clearance (Clf) increased from 1,840 L/hour to 2,360 L/hour after 13cisRA dosing (Figure 4 and Table 2 ). Taken together, these results suggest 13cisRA is potentially a weak CYP2D6 inducer. The data also suggest that 13cisRA is a weak CYP3A4 inducer. The CYP3A4 mediated Clf of 3‐methoxymorphinan increased from 22 to 31 L/hour, and the mean Clf of 6β‐hydroxycortisol, an endogenous CYP3A4 probe, increased from 36 to 53 mL/hour after 13cisRA dosing (Table 2 and Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

Serum concentration‐time profiles of the study drugs and the pharmacokinetic measures of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity markers. Panel (a) shows the serum concentration vs. time profiles for 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (13cis RA) (circles) and its metabolites 4‐oxo‐13cis RA (squares), and all‐trans‐retinoic acid (at RA) (triangles) following the final 40 mg dose of 13cis RA on study day 15. Panels (b,c) show the serum concentrations of dextromethorphan (b) and dextrorphan (c) on study days 1 (prior to 13cis RA dosing, circle with solid line) and 15 (after 13cis RA dosing, square with dashed line). Concentration data are presented as mean and range of individual values (n = 8). Insets are data presented on semilog scale. The calculated formation clearances (Clf) of dextromethorphan metabolites dextrorphan (d) and 3‐methoxymorphinan (e) on the two study days are shown for seven subjects. One subject was identified as an outlier and removed from all analyses involving urine data. Panel (f) shows 6β‐hydroxycortisol Clf on the two study days in six subjects. One subject had no measurable 6β‐hydroxycortisol in urine collected from study day 15 and was excluded.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for dextromethorphan and dextrorphan and formation clearance of the two CYP3A4 markers 3‐methoxymorphinan and 6β‐hydroxycortisol before (control) and after 13 cis RA dosing (treatment)

| Control mean (%CV) | Treatment mean (%CV) | Treatment/control GMR (90% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dextromethorphan | |||

| Cmax (nM) | 3.59 (109) | 3.00 (104) | 0.829 (0.698–0.985) |

| AUC0–∞ (hour × nM) | 28.4 (127) | 23.3 (119) | 0.822 (0.677–0.998) |

| Cl/f (L/hour) | 3,870 (94) | 4,750 (102) | 1.23 (1.02–1.48) |

| t1/2 (hour) | 5.07 (30) | 5.03 (34) | 0.991 (0.831–1.18) |

| Dextrorphan | |||

| Cmax (nM) | 11.1 (44) | 10.8 (29) | 0.971 (0.747–1.26) |

| AUC0–∞ (hour × nM) | 51.3 (43) | 52.9 (29) | 1.03 (0.851–1.25) |

| Clf (L/hour)a | 1,840 (106) | 2,360 (121) | 1.29 (1.05–1.58) |

| AUCm/AUCp | 1.81 (78) | 2.28 (69) | 1.25 (0.998–1.57) |

| Um/Up a | 153 (70) | 173 (72) | 1.13 (0.817–1.56) |

| 3‐methoxymorphinan | |||

| Clf (L/hour)a | 22.1 (107) | 30.7 (135) | 1.39 (1.05–1.84) |

| 6β‐hydroxycortisol | |||

| Clf (mL/hour)a | 35.6 (48) | 52.8 (29) | 1.49 (0.993–2.24) |

AUC0−∞, area under the concentration‐time curve from zero to infinity; AUCm, the area under concentration curve of the metabolite; AUCp, the area under concentration curve of parent drug; %CV, percentage of coefficient of variation; CI, confidence interval; Clf, formation clearance; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; CYP, cytochrome P450; GMR, geometric mean ratio; RA, retinoic acid; t1/2, terminal half‐life; Um, amount of metabolite excreted into urine; Up, amount of parent drug excreted into urine.

n = 7. The urinary recovery of two analytes from one subject in the 0–8 hour collection on study day 1 were determined to be outliers by the Grubb's test, and all data from this subject based on urinary measures were excluded from analysis.

All pharmacokinetic parameters are shown as geometric means with a %CV.

Changes in mRNA in mouse liver

The hypothesis of this study was based on prior data in CYP2D6 humanized mice in which atRA treatment alone resulted in CYP2D6 downregulation and Shp induction.6 Therefore, to delineate the effects of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA, their effects on Shp and mouse Cyp2d mRNAs were measured in vivo in mice in addition to the retinoid target genes, which were included as positive controls (Figure 5 ). The RAR target gene Cyp26a1 was significantly induced after treatment with all three retinoids, and 13cisRA and atRA dosing also resulted in a decrease in the Shp target gene Cyp8b1 but not Cyp7a1, a weaker Shp target (Figure 5 ). Surprisingly, 13cisRA had no effect on mouse Cyp2d mRNAs and atRA only decreased Cyp2d9 and Cyp2d10 mRNA (Figure 5 ). In contrast, 4‐oxo‐13cisRA resulted in induction of nearly all Cyp2d isoforms and Shp (Figure 5 ), demonstrating clear retinoid‐dependent effects in mice and a disconnect between Shp induction and Cyp2d downregulation.

Figure 5.

Effects of 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (13cis RA), all‐trans‐retinoic acid (at RA), or 4‐oxo‐13cis RA on cytochrome P450 (CYP) mRNA expression in mouse livers following treatment with each study retinoid. The mice (n = 6 for each treatment) were treated for 4 days with each retinoid at 5 mg/kg i.p. as described in the Methods section and the fold change in small heterodimer partner (Shp) and Cyp mRNA expression (black bars) was evaluated in comparison to vehicle controls (white bars). The panels show mRNA data after treatment with 13cis RA (a), at RA (b), or 4‐oxo‐13cis RA (c), and the insets provide P values calculated for each gene compared to control as described in methods. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Recent studies have suggested that in vitro CYP downregulation by small molecules translates to clinical DDIs,4, 18, 22 but the data on IVIVE of CYP downregulation are controversial. The data obtained here show that concurrent downregulation of CYP2D6 mRNA and induction of CYP3A4 in human hepatocytes in the absence of cytotoxicity does not unequivocally translate to in vivo DDIs. This is important as retinoids do not inhibit CYP2D6 or CYP3A4, and therefore, they provide a model system to evaluate IVIVE of downregulation. The data collected show a clear disconnect in IVIVE with in vitro CYP2D6 downregulation translating to induction of CYP2D6 in the clinic. These data are similar to previous findings in dogs,23 in which an investigational drug was shown to downregulate CYP1A mRNA in beagle hepatocytes yet in vivo studies showed CYP1A induction. In contrast, transcriptional downregulation and increased proteasomal degradation of CYPs in response to increased proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)‐6 and IL‐1β24, 25, 26 corresponds to in vivo suppression of CYPs. After treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with anti‐IL‐6 antibodies, the exposure of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 substrates decreased.27, 28 However, existing information5, 23 coupled with the data collected in this study, suggests that unlike cytokine‐mediated CYP downregulation, small molecule–mediated CYP downregulation in vitro does not necessarily translate to in vivo decreases in enzyme activity.

It is likely that the lack of translation of in vitro downregulation to in vivo DDI is dependent on the mechanism of regulation of enzyme expression, and more studies are needed to identify mechanisms of CYP downregulation. The existing data suggest that the mechanisms that result in CYP3A4 induction, CYP2D6 downregulation and RAR, and CYP26A1 induction after retinoid exposure are distinct and independent of each other. Induction of CYP3A4 by retinoids in hepatocytes seems to be mediated by PXR activation, and this PXR activation translated to weak CYP3A4 induction in vivo (1.4‐fold increase in the Clf of 3‐methoxymorphinan, and 6β‐hydroxycortisol). Similarly, all study subjects showed side effects related to RAR activation, and retinoids are well known to induce the expression of the CYP26 enzymes in vivo, as also shown here, in human hepatocytes and in mice. In contrast, based on the CYP2D6 mRNA downregulation in the same human hepatocytes, and the clinical data collected in parallel for CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity, the in vitro data could not predict the weak CYP2D6 induction following 13cisRA treatment. It is noteworthy that the PXR‐mediated CYP3A4 induction was predictable, yet the CYP2D6 regulation was not. One possible contributing factor for the discrepant predictability could be in vitro and/or clinical variability. Large intrahepatocyte and interhepatocyte donor variability for CYP3A4 mRNA induction by rifampin and other prototypical CYP3A4 inducers were recently reported.29 Similar variability was observed in this study, but the responsiveness to retinoid treatments was defined by the donor and replicate rather than the target enzyme or mechanism. The downregulation of CYP2D6 by atRA has been suggested to be a result of induction of the transcriptional corepressor SHP. Consistent with previous mouse and in vitro studies,7, 8, 9, 30 atRA, as well as 13cisRA and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA, induced SHP in human hepatocytes in this study. As previously reported,9, 30 Shp induction and Cyp8b1 downregulation were also observed in vivo in mice, but mouse Cyp2ds were not decreased with Shp induction. This is in agreement with previous work in which knockout of Shp in a CYP2D6 humanized mouse model had inconsistent effects on basal CYP2D6 expression.6, 31 Overall, our data failed to demonstrate a correlation between SHP induction and CYP2D6 downregulation. Together with the literature results, our findings suggest that the effects of retinoids on CYPs are complex and involve multiple nuclear receptors.8, 32, 33 It is possible that endogenous regulators of these pathways in vivo, such as bile acids, and stellate cell and Kupffer cell–derived factors, are not well represented in vitro resulting in IVIVE disconnect. Induction of Cyp2d in mice and CYP2D6 in the clinical study is in agreement with the observed increase in Cyp2d11, Cyp2d22, Cyp2d26, and Cyp2d40 mRNA and activity in mice during pregnancy and corresponding increase in RA signaling in the maternal liver during pregnancy.34 Yet, this could be a mouse‐specific finding as a retinoic acid response element has been identified in the Cyp2d40 promoter.34

The data shown here also illustrate the relevance of testing the effects of major circulating metabolites on CYP expression. All the data shown suggest that the major circulating and active metabolite, 4‐oxo‐13cisRA, would be the main contributor to the retinoid‐CYP2D6 and retinoid‐CYP3A4 interactions. In addition, in mice 4‐oxo‐13cisRA had the greatest effect on Cyp26a1, an RAR target gene. The 4‐oxo‐13cisRA–induced mouse Cyp2d isoform expression and in human hepatocytes 4‐oxo‐13cisRA caused the greatest CYP3A4 induction. The 4‐oxo‐13cisRA also had the highest unbound circulating concentrations following 13cisRA dosing making it the likely main precipitant of DDIs.

In conclusion, the findings presented here demonstrate suppression of CYP2D6 and induction of CYP3A4 in human hepatocytes. However, 13cisRA, likely via the activity of its major circulating metabolite 4‐oxo‐13cisRA, is a weak inducer of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 clinically. This induction may be clinically relevant when 13cisRA is coadministered with CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 substrates with narrow therapeutic indexes. These data demonstrate the difficulty in translating observations of enzyme downregulation to clinical DDIs and show that further work is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms of downregulation observed in preclinical studies.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants T32 GM007750 (F.S.) and TL1 TR000422 (F.S.), P01 DA032507 (N.I.), a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant K24 HD082231 (J.K.A.), and an American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education Pre‐Doctoral Award in Pharmaceutical Sciences (F.S.).

Conflict of Interest

As an Associate Editor for Clinical and Translational Science, N.I. was not involved in the review or decision process for this paper.

Author Contributions

F.S., M.K., J.R.K., S.W., C.H., and N.I. wrote the manuscript. F.S., M.K., J.R.K., S.W., C.H., J.K.A., and N.I. designed the research. F.S., M.K., S.W., C.H., and J.K.A. performed the research. F.S. and M.K. analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Supplementary Methods and Figures

Figure S1. The effects of treatment with 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on SHP mRNA in donor 1 (a,b,c), donor 2 (d,e,f), and in three replicate experiments in donor 3 (g–o) hepatocytes.

Figure S2. The effects of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on CYP2D6 activity in donor 1 (a,b,c), donor 2 (d,e,f), and in three replicate experiments in donor 3 (g–o) hepatocytes.

Figure S3. The effects of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on CYP3A4 mRNA (white bars) and activity (hashed bars) in two replicate experiments in donor 3.

Figure S4. Activation of PXR by 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA in PXR reporter assay.

Figure S5. Concentrations vs. time curves of the retinoids in human hepatocytes following treatment with 1 μM 13cisRA, atRA, or 4‐oxo‐13cisRA.

Figure S6. Change in expression of RARβ mRNA in human hepatocytes following treatment with vehicle control (open bars), 13cisRA (black bars), atRA (horizontal striped bars), or 4‐oxo‐13cisRA (vertical striped bars).

Table S1. The fitted values for indivudal experiment CYP2D6 downregulation in donor 3 in figure 1.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Iris Nelson for her assistance in study coordination.

References

- 1. European Medicines Agency (EMA) . Guideline on the investigation of drug interactions. <https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-investigation-drug-interactions_en.pdf> 2012).

- 2. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . Clinical Drug Interaction Studies – Study Design, Data Analysis, and Clinical Implications Guidance for Industry. <https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm292362.pdf> (2017).

- 3. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . In Vitro Metabolism‐ and Transporter‐Mediated Drug‐Drug Interaction Studies Guidance for Industry. <https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM581965.pdf> (2017).

- 4. Intercept Pharmaceuticals Inc. OCALIVA (obeticholic acid) package insert. NDA number 207999. <https://ocalivahcp.com/> (2016).

- 5. Hariparsad, N. et al Considerations from the IQ Induction Working Group in Response to Drug‐Drug Interaction Guidance from Regulatory Agencies: focus on downregulation, CYP2C induction, and CYP2B6 positive control. Drug Metab. Dispos. 45, 1049–1059 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koh, K.H. et al Altered expression of small heterodimer partner governs cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 induction during pregnancy in CYP2D6‐humanized mice. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 3105–3113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mamoon, A. , Ventura‐Holman, T. , Maher, J.F. & Subauste, J.S. Retinoic acid responsive genes in the murine hepatocyte cell line AML 12. Gene 408, 95–103 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai, S.‐Y. , He, H. , Nguyen, T. , Mennone, A. & Boyer, J.L. Retinoic acid represses CYP7A1 expression in human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells by FXR/RXR‐dependent and independent mechanisms. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2265–2274 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang, F. et al All‐trans retinoic acid regulates hepatic bile acid homeostasis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 91, 483–489 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sass, J.O. , Forster, A. , Bock, K.W. & Nau, H. Glucuronidation and isomerization of all‐trans‐ and 13‐CIS‐retinoic acid by liver microsomes of phenobarbital‐ or 3‐methylcholanthrene‐treated rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47, 485–492 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen, H. & Juchau, M.R. Glutathione S‐transferases act as isomerases in isomerization of 13‐cis‐retinoic acid to all‐trans‐retinoic acid in vitro. Biochem. J. 327, 721–726 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baron, J.M. et al Retinoic acid and its 4‐oxo metabolites are functionally active in human skin cells in vitro. J. Invest. Dermatol. 125, 143–153 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sonawane, P. et al Metabolic characteristics of 13‐cis‐retinoic acid (isotretinoin) and anti‐tumour activity of the 13‐cis‐retinoic acid metabolite 4‐oxo‐13‐cis‐retinoic acid in neuroblastoma. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 5330–5344 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang, K. , Chen, S. , Xie, W. & Wan, Y.‐J.Y. Retinoids induce cytochrome P450 3A4 through RXR/VDR‐mediated pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 75, 2204–2213 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen, S. , Wang, K. & Wan, Y.‐J.Y. Retinoids activate RXR/CAR‐mediated pathway and induce CYP3A. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79, 270–276 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halladay, J.S. , Wong, S. , Khojasteh, S.C. & Grepper, S. An ‘all‐inclusive’ 96‐well cytochrome P450 induction method: measuring enzyme activity, mRNA levels, protein levels, and cytotoxicity from one well using cryopreserved human hepatocytes. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 66, 270–275 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amory, J.K.K. et al Isotretinoin administration improves sperm production in men with infertility from oligoasthenozoospermia: a pilot study. Andrology 5, 1115–1123 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sager, J.E. et al In vitro to in vivo extrapolation of the complex drug‐drug interaction of bupropion and its metabolites with CYP2D6; simultaneous reversible inhibition and CYP2D6 downregulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 123, 85–96 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fahmi, O.A. et al A combined model for predicting CYP3A4 clinical net drug‐drug interaction based on CYP3a4 inhibition, inactivation, and induction determined in vitro. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36, 1698–1708 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lutz, J.D. & Isoherranen, N. Prediction of relative in vivo metabolite exposure from in vitro data using two model drugs: dextromethorphan and omeprazole. Drug Metab. Dispos. 40, 159–168 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Templeton, I. et al Accurate prediction of dose‐dependent CYP3A4 inhibition by itraconazole and its metabolites from in vitro inhibition data. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 88, 499–505 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zamek‐Gliszczynski, M.J. , Mohutsky, M.A. , Rehmel, J.L.F. & Ke, A.B. Investigational small‐molecule drug selectively suppresses constitutive CYP2B6 activity at the gene transcription level: physiologically based pharmacokinetic model assessment of clinical drug interaction risk. Drug Metab. Dispos. 42, 1008–1015 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibson, C.R. et al Induction of CYP1A in the beagle dog by an inhibitor of kinase insert domain‐containing receptor: differential effects in vitro and in vivo on mRNA and functional activity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 33, 1044–1051 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dickmann, L.J. , Patel, S.K. , Rock, D.A. , Wienkers, L.C. & Slatter, J.G. Effects of interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and an anti‐IL‐6 monoclonal antibody on drug‐metabolizing enzymes in human hepatocyte culture. Drug Metab. Dispos. 39, 1415–1422 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee, C.M. , Pohl, J. & Morgan, E.T. Dual mechanisms of CYP3A protein regulation by proinflammatory cytokine stimulation in primary hepatocyte cultures. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37, 865–872 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dickmann, L.J , Patel, S.K. , Wienkers, L C. & Slatter, J.G. Effects of interleukin 1β (IL‐1β) and IL‐1β/interleukin 6 (IL‐6) combinations on drug metabolizing enzymes in human hepatocyte culture. Curr. Drug Metab. 13, 930–937 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schmitt, C. , Kuhn, B. , Zhang, X. , Kivitz, A. & Grange, S. Disease‐drug‐drug interaction involving tocilizumab and simvastatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 89, 735–740 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhuang, Y. et al Evaluation of disease‐mediated therapeutic protein‐drug interactions between an anti‐interleukin‐6 monoclonal antibody (sirukumab) and cytochrome P450 activities in a phase 1 study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using a cocktail approach. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 55, 1386–1394 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kenny, J.R. et al Considerations from the IQ Induction Working Group in Response to Drug‐Drug Interaction Guidances from Regulatory Agencies: focus on CYP3A4 mRNA in vitro response thresholds, variability, and clinical relevance. Drug Metab. Dispos. 46, 1285–1303 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mamoon, A. , Subauste, A. , Subauste, M.C. & Subauste, J. Retinoic acid regulates several genes in bile acid and lipid metabolism via upregulation of small heterodimer partner in hepatocytes. Gene 550, 165–170 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pan, X. , Lee, Y.‐K. & Jeong, H. Farnesoid X receptor angonist represses cytochrome P450 2D6 expression by upregulating small heterodimer partner. Drug Metab. Dispos. 43, 1002–1007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pan, X. & Jeong, H. Estrogen‐induced cholestasis leads to repressed CYP2D6 expression in CYP2D6‐humanized mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 88, 106–112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pan, X. , Kent, R. , Won, K.‐J. & Jeong, H. Cholic acid feeding leads to increased CYP2D6 expression in CYP2D6‐humanized mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 45, 346–352 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Topletz, A.R. et al Hepatic Cyp2d and Cyp26a1 mRNAs and activities are increased during mouse pregnancy. Drug Metab. Dispos. 41, 312–319 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods and Figures

Figure S1. The effects of treatment with 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on SHP mRNA in donor 1 (a,b,c), donor 2 (d,e,f), and in three replicate experiments in donor 3 (g–o) hepatocytes.

Figure S2. The effects of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on CYP2D6 activity in donor 1 (a,b,c), donor 2 (d,e,f), and in three replicate experiments in donor 3 (g–o) hepatocytes.

Figure S3. The effects of 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA on CYP3A4 mRNA (white bars) and activity (hashed bars) in two replicate experiments in donor 3.

Figure S4. Activation of PXR by 13cisRA, atRA, and 4‐oxo‐13cisRA in PXR reporter assay.

Figure S5. Concentrations vs. time curves of the retinoids in human hepatocytes following treatment with 1 μM 13cisRA, atRA, or 4‐oxo‐13cisRA.

Figure S6. Change in expression of RARβ mRNA in human hepatocytes following treatment with vehicle control (open bars), 13cisRA (black bars), atRA (horizontal striped bars), or 4‐oxo‐13cisRA (vertical striped bars).

Table S1. The fitted values for indivudal experiment CYP2D6 downregulation in donor 3 in figure 1.