Abstract

We developed the Quality of Contraceptive Counseling (QCC) Scale to improve measurement of client experiences with providers in the era of rights‐based service delivery. We generated scale items drawing on the previously published QCC Framework and qualitative research on women's preferences for counseling in Mexico, and refined them through cognitive interviews (n = 29) in two Mexican states. The item pool was reduced from 35 to 22 items after pilot testing using exit interviews in San Luis Potosí (n = 257). Exploratory Factor Analysis revealed three underlying dimensions (Information Exchange, Interpersonal Relationship, Disrespect and Abuse); this dimensionality was reproduced in Mexico City (n = 242) using Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Item Response Theory analyses confirmed acceptable item properties in both states, and correlation analyses established convergent, predictive, and divergent validity. The QCC Scale and subscales fill a gap in measurement tools for ensuring high quality of care and fulfillment of human rights in contraceptive services, and should be evaluated and adapted in other contexts.

The international family planning field has had a strong focus on quality of care in contraceptive services since the early 1990s (Bruce 1990; Jain, Bruce, and Kumar 1992). Quality of care has been widely measured and monitored using tools derived from the seminal quality framework published by Judith Bruce (Bruce 1990; Miller et al. 1997; Sullivan and Bertrand 2001; RamaRao and Mohanam 2003).This prioritization of quality has historically been motivated by a recognition that positive client experiences are essential to acceptance and use of contraceptive methods (Jain, Bruce, and Kumar 1992; Jain, Bruce, and Mensch 1992; Lei et al. 1996; Mensch, Arends‐Kuenning, and Jain 1996; Koenig, Hossain, and Whittaker 1997; Mroz et al. 1999; Canto De Cetina, Canto, and Ordonez Luna 2001; Blanc, Curtis, and Croft 2002; Koenig, Ahmed, and Hossain 2003; RamaRao, Lacuesta, Costello et al. 2003; Arends‐Kuenning and Kessy 2007; Abdel‐Tawab and RamaRao 2010; Jain et al. 2012). Positive experiences are also increasingly recognized as critical to promoting confidence in the health care system (Kruk et al. 2018), and as an important end goal in and of themselves, as has been underscored by the recent articulation of human rights frameworks for family planning service delivery (Hardee et al. 2013; WHO 2014) and an update to the Bruce quality framework that explicitly engages with rights principles (Jain and Hardee 2018).

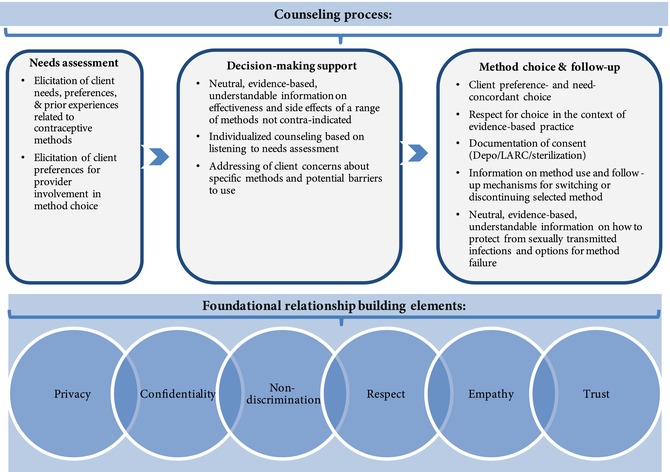

The “heart” of high quality contraceptive service delivery is the communication between the client and provider. This interaction is important both in terms of the information exchanged and the interpersonal relationship (Bruce 1990; Jain and Hardee 2018). Members of our team recently synthesized best practices in contraceptive counseling, the health communication literature, and human rights guidelines to define a new Quality in Contraceptive Counseling (QCC) Framework (Figure 1) (Holt, Dehlendorf, and Langer 2017). This framework displays at a more granular level than general quality of care frameworks what an ideal interaction between a client and a provider entails. The steps for high‐quality counseling are depicted in the QCC Framework as occurring on the building blocks of several human rights principles selected as being relevant for client‐provider interactions (privacy, confidentiality, nondiscrimination) (WHO 2014), as well as concepts from the health communication literature fundamental for interpersonal quality of care (respect, empathy, trust).

Figure 1.

Quality in contraceptive counseling

Reprinted from Contraception 96(3), Kelsey Holt, Christine Dehlendorf, Ana Langer, “Defining quality in contraceptive counseling to improve measurement of individuals' experiences and enable service delivery improvement,” page 5, copyright 2017, with permission from Elsevier.

Despite the importance of contraceptive counseling, existing quality measurement tools are insufficient for measuring perceptions of all dimensions of the counseling interaction as detailed in the QCC Framework. First, widely used questions tend to focus on receipt of information and are limited in their ability to measure the interpersonal aspects of care such as trust or decision‐support. Second, questions about client experience are typically framed positively, without any direct probes for whether mistreatment or coercion of women occurred. Directly probing for negative experiences—as is now being done widely in the maternal health field (Harris, Reichenbach, and Hardee 2016; Holt, Caglia, Peca et al. 2017; Sando et al. 2017)—would help align measurement tools with the new focus on rights‐based service delivery. Finally, existing measurement tools have not been assessed psychometrically for reliability and validity across settings (i.e., the extent to which they provide precise, unbiased measurement of clients’ experiences with counseling in different settings is unknown).

We sought to contribute to efforts to improve measurement of women's experiences with contraceptive services in this new era of rights‐based service delivery by creating the Quality of Contraceptive Counseling (QCC) Scale based on the QCC Framework (Holt, Dehlendorf, and Langer 2017). To ensure the scale's relevance in Mexico, the setting for development and validation, item composition was based on prior research into women's expressed preferences for contraceptive care conducted for these purposes (Holt et al. 2018). Dissemination of such a tool shows particular promise for improving quality of care in Mexico as the current strategic plan of the national family planning program includes a focus on quality of care (Programa Sectoral de Salud 2014). A recent study highlighted the need for quality improvement efforts in Mexico by identifying deficiencies in individuals’ experiences, particularly among adolescents (Darney et al. 2016).

In this article, we describe the process of developing and validating the QCC Scale through a series of activities over a two‐year period (2016–18). These activities were conducted with the specific purpose of constructing the QCC Scale as a new measure of client experience communicating with contraception providers.

METHODS

Overview

The process of developing and validating the QCC Scale involved: 1) generating an initial pool of items for testing; 2) modifying items based on cognitive interviews with contraception clients in San Luis Potosí and Mexico City; 3) piloting the scale with contraception clients in San Luis Potosí to quantitatively assess item distributions and properties, and how items relate to each other such that they appear to be coherently measuring the same underlying construct, using both Classical Test Theory (CTT) and Item Response Theory (IRT) techniques; 4) triangulating findings to make a final decision about which items to retain; 5) piloting the scale in Mexico City to see if it produced consistent quantitative results; and 6) examining the degree to which scale scores correlated with other measures in both cities, suggesting it is measuring the intended construct. We describe each of these steps in detail.

Development of Quality of Contraceptive Counseling Scale Item Pool

Item Generation

We aimed to generate at least one item to represent each component of the QCC Framework (Holt, Dehlendorf, and Langer 2017), thereby ensuring content validity by covering the entire construct. The first three authors (all native or fluent Spanish speakers) met repeatedly to compose an initial pool of 37 items in Spanish. Items were composed to reflect specific language used by contraception clients when discussing their preferences for communicating with providers in a formative focus group study conducted specifically for the purpose of developing the QCC Scale (Holt et al. 2018). The scale is designed to be applicable to all scenarios in which women discuss contraception with providers (e.g., dedicated family planning visits for new or returning users, prenatal visits, post‐abortion counseling), and to produce comparable composite scores regardless of whether women received any information at all or chose to use a method.

Cognitive Interviews

Sample

We conducted interviews with 29 women recruited in a convenience sample of primary health care clinics in two states1 in Mexico: Mexico City and San Luis Potosí. These two entities were selected to ensure participation of a wide range of women: those from the mostly progressive capital city of Mexico City (an urban area with almost 9 million inhabitants) (n = 20), and those from a more conservative state (San Luis Potosí) with a smaller population of 3 million inhabitants and both urban and rural municipalities (n = 9). San Luis Potosí and Mexico City differ on numerous socio‐demographic indicators, including percentage of the population that is Catholic (89 percent versus 82 percent, respectively), indigenous (23 percent versus 9 percent), with internet access (27 percent versus 58 percent), and economically active (47 percent versus 56 percent) (INEGI 2013 and 2016). The extent to which San Luis Potosí is a more conservative state than Mexico City, particularly related to reproductive health, is evidenced by the fact that first‐trimester abortion is considered a punishable crime (with the exception of when the woman's life is in danger or the pregnancy is a result of rape) compared to Mexico City where first‐trimester abortion is legal (Código Penal Distrito Federal 2017; Código Penal San Luis Potosí 2018).

The majority of participants (n = 25) were recruited from four clinics under the jurisdiction of the Health Secretariat in Mexico, which provides services across the country to the population not employed in the formal sector. In this system, family planning policy ensures availability of a full range of contraceptive methods (including pills, injectables, IUDs, implant, patch, sterilization, emergency contraception, and condoms) without cost. We recruited the remaining four participants from three private clinics affiliated with the nonprofit organization Mexfam. A similar mix of methods is available at low cost to patients within this system which targets a middle‐class population.

Eligibility criteria included being female and having spoken with a provider about contraception on the day of recruitment. The Harvard Chan School Institutional Review Board approved of plans for cognitive interviews and the exit interview study described below. Additionally, a local advisory board, consisting of three individuals not involved in the proposed research, was assembled to review and provide feedback on study plans and materials from the perspective of women seeking contraception.

Data Collection

Recruitment for cognitive interviews took place in waiting rooms of study sites between September 2016 and February 2017. On recruitment days, interviewers (members of the Mexfam research and evaluation team trained by the investigators in how to conduct cognitive interviews) approached all women who appeared to be of reproductive age to invite them to participate in an exit interview about their experiences that day with contraceptive counseling. Receptionists also gave flyers to patients and directed them to interviewers. After participants gave their consent, interviews were conducted in private areas of study sites. Interviews consisted of administering the scale to participants and pausing after each question to ask participants to describe how and why they arrived at their answer, and whether the item was confusing or difficult to respond to. Cognitive interviews lasted 30–45 minutes.

Analysis

Detailed, handwritten notes were recorded by interviewers and later entered into Excel. Notes for each participant were categorized into four themes per item: 1) how participants arrived at their answer, 2) any inconsistencies noted by interviewers in how participants responded to similar items (a potential indication that items were not being interpreted as intended), 3) participants’ indications of how salient the item was to their own definition of a good experience with counseling, and 4) how easy the question was to answer. Through a series of multiple, multi‐hour phone meetings, the first three authors and two additional interviewers collectively reviewed the findings under these four headings, going item by item to make decisions about necessary item deletion or rewording. Item changes were made to ensure consistent interpretation of items and clarity. The item pool was refined and reduced to 35 items through this process.

QCC Scale Testing and Item Reduction

Sample

Because client report of quality of counseling can be expected to be clustered by provider, we encouraged variability in patient experience within our sample and greater generalizability within the Health Secretariat system in the two states by recruiting in a convenience sample of eight public clinics in each city and two public hospitals in San Luis Potosí, for a total of 18 sites. In San Luis Potosí, both rural and urban sites were included. In line with standard recommendations for sample size to conduct factor analysis (DeVellis 2011), our planned sample size was 250 structured client exit interviews in each state (500 in total) to allow for separate analyses by state.

Data Collection

Exit interview recruitment took place between February and July 2017 using the same procedures and eligibility criteria described above for cognitive interviews. Exit interviews were administered in private areas of clinics/hospitals by study staff not affiliated with the clinic/hospital and took 30 minutes on average. Follow‐up telephone interviews (5 minutes) were designed to take place between 30–60 days post‐visit to assess short‐term contraceptive use, satisfaction, and needs for participants who provided their contact information at baseline.

Measures

The baseline exit interview instrument included the 35‐item QCC Scale, overall experience rating questions used to assess scale validity, and participant and visit background characteristics. Follow‐up telephone interviews included assessment of contraceptive use and satisfaction, and informational needs.

Scale Items

The 35 items comprising the QCC Scale were each administered with a four‐point response scale. Response categories for positively worded items were “completely agree/totalmente de acuerdo,” “agree/de acuerdo,” “disagree/en desacuerdo,” and “completely disagree/totalmente en desacuerdo.” Response categories for negatively worded items were “yes/sí,” “yes with doubts/sí con dudas,” “no with doubts/no con dudas,” and “no/no.”

Overall Experience Ratings

We assessed overall perception of the interaction with the provider by asking a general question about the experience with the provider, with response options on a four‐point scale ranging from very good to very bad. For divergent validity purposes, we assessed participants’ perception of the waiting room (response options also ranged from very good to very bad).

Contraceptive Use and Reproductive Intentions

We asked women whether they would like to prevent a pregnancy (Yes, Unsure, No, Currently Pregnant), and whether they planned to use the method they selected that day, or continue the method they were already using (Yes, Unsure, No).

Participant and Visit Background Characteristics

We collected information on women's age, education status, occupation, number of children, sexual orientation and gender identity, and marital status. We also asked about the type of provider a participant spoke to about contraception on the day of the interview, the sex of the provider, and the reason for their visit.

Follow‐up Interviews

In the follow‐up telephone interview, we asked women whether they were currently using a method (Yes, No); if so, whether they were satisfied with that method (Very Satisfied, Somewhat Satisfied, Somewhat Unsatisfied, Very Unsatisfied); and if they needed more information about contraceptive methods at that point in time (Yes, No).

Analysis

The factor structure of the scale was assessed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Individual item properties were examined using both CTT and IRT. These analyses were used in an iterative manner, and findings from each were triangulated to reduce the item pool and construct the final 22‐item QCC Scale. Considerations of content validity, drawing upon the measurement framework (Holt, Dehlendorf, and Langer 2017) to make sure the full range of the QCC construct was covered, were prioritized when deciding whether an item would ultimately be removed after examining statistical analyses. Construction of the scale was performed on data from San Luis Potosí. We then conducted confirmatory analyses to assess whether the items and scale performed consistently in Mexico City, using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and IRT. Finally, convergent, divergent, and predictive validity were examined through analyses of the correlation of QCC Scale scores with other variables collected at baseline and follow‐up. We ran complete case analyses for all models.

Factor Analysis

Because dimensions of the QCC construct are conceived of as highly interrelated and expected to be correlated, oblique rotation of factors was used for the EFA. A scree test was used to examine the number of factors identified by the “elbow” on the plot (Cattell 1966). Items not loading at least 0.5 on their dominant factor—or loading more than 0.3 on secondary factors—were considered for removal unless there was a strong justification from a content validity perspective to retain them. We examined correlations between subscale scores using Pearson correlation coefficients to assess the degree to which there was evidence for a unifying underlying QCC construct. We conducted CFA to determine the extent to which the factor structure identified in San Luis Potosí was compatible with Mexico City data.

Classical Test Theory

Descriptive statistics calculated for each item included category frequencies, means, and standard deviations. Inter‐item correlations and item‐rest correlations were examined to characterize the relationship between items. Internal consistency reliability was calculated using Cronbach's alpha, with the goal of reaching a 0.7 or greater for the final scale and subscales. During item selection, excluded item alphas were assessed to see if removal of a given item changed the Cronbach's alpha score notably (more than 0.2).

Item Response Theory

Using a 2‐parameter graded response model for a categorical outcome, we examined performance of individual items in terms of “difficulty” and “discrimination” parameters. Difficulty parameters—estimated for each response boundary of a categorical variable (e.g., the boundary between Agree and Strongly Agree)—provide a relative measure of how positive an experience would have to be for a member of this population to rate their experience as one step higher on the scale of 1–4 (e.g., to choose Strongly Agree over Agree). Items with very low or very high relative difficulty parameters, or items where difficulty parameters for the category boundaries are very close (indicating not much difference in underlying quality between category boundaries) were considered for removal. Discrimination parameters are calculated for each item overall (i.e., not specific to the category boundary as is the case with difficulty parameters) and give a sense of the amount of information about the underlying experience of quality a particular item provides for a population. In other words, discrimination parameters provide a measure of how well individual items differentiate between individuals experiencing different underlying levels of quality. Items with relatively low discrimination compared to the set were considered for removal. Typical difficulty parameters range from –3 to 3, and discrimination values for multiple‐choice items are typically under 2 (Harris 1989).

This IRT model assumes a unidimensional latent trait—i.e., that scale items are measuring a single underlying construct (quality of counseling) (Harris 1989). Because we anticipated using the QCC Scale to produce composite scores for quality monitoring purposes, we considered this IRT assumption appropriate even though we were simultaneously using factor analysis to identify any subconstructs. However, before running IRT models (and finalizing recommendations for construction of composite scores), we made sure factor analysis results yielded subscales inter‐correlated by Pearson r ≥ .3 as this would indicate sufficient connections between any identified subscales.

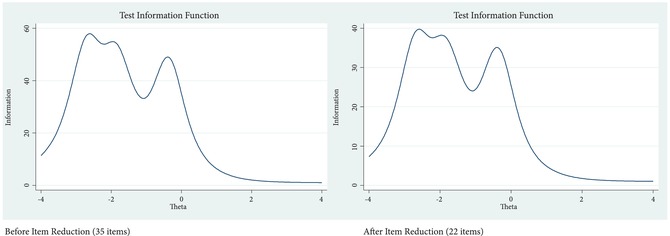

Test Information Functions were used to compare the level of information provided at different levels of reported quality between the full and reduced versions of the scale to ensure there was not a loss of information around the most common participant QCC score range.

Score Construction

We examined descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skew, kurtosis) for composite QCC scores and subscores. Composite scores were calculated using a simple mean of all relevant item responses on the 4‐point response scale. Sum scores were used rather than the “theta” scores generated by the IRT model that take into account the fact that intervals between response options are not equal. Though theta scores are superior, because they are based on IRT models that model this variability in intervals between response options, they are not practical for use in health‐care settings where data analysis leveraging IRT models is not always feasible. In instances where use of IRT models to calculate scores may be possible—for example, in research contexts—use of IRT to generate theta scores from the QCC Scale may be desirable.

Correlation Analysis

Convergent validity—or the degree to which QCC Scale scores correlate with other similar measures as we expect they should if they are measuring the intended underlying construct—was assessed using the overall measure of patient experience with the provider and the measure of whether they planned to use/continue using the selected contraceptive method (among those who reported selecting or already having a method on the day of the interview).

Divergent validity—or the degree to which QCC Scale scores do not correlate with unrelated measures as we expect they shouldn't if they are measuring the intended construct—was assessed using the variable measuring patients’ perception of the waiting room. This variable was chosen a priori because we believed that a person's assessment of waiting room quality should be largely unrelated to their assessment of interpersonal quality of care if the QCC Scale has been well designed to isolate measurement of counseling experience.

Predictive validity—or the degree to which QCC Scale scores are correlated with variables measured at a later point in time—was assessed using the questions from the follow‐up interview related to whether an individual was using a contraceptive method and whether they reported their needs for information about contraceptive methods were currently met. We chose these variables to assess predictive validity because we expected them to correlate with higher QCC scores at baseline if QCC scores were successfully measuring the intended construct. For the analysis of contraceptive use at follow‐up, only participants who had indicated at baseline that they desired pregnancy prevention, or who were not currently pregnant, were included.

These analyses were conducted using bivariate regression models. Robust standard errors were calculated to account for clustering by provider.

RESULTS

Item Development

The pool of 35 items finalized after cognitive interviews is displayed in Table 1. One major change made after cognitive interviews was to the response options for negatively worded items. Early cognitive interview participants found the “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree” response scale difficult to interpret and we iteratively tested alternative options. Ultimately, the “Yes,” “Yes with doubts,” “No with doubts,” “No,” response scale was determined to be easiest to interpret. More information about the adjustments made to items based on cognitive interview findings is available upon request.

Table 1.

Item descriptive statistics, Quality of Contraceptive Counseling (QCC) Scale, San Luis Potosí and Mexico Citya (N=499)

| Mean(SD) | |

|---|---|

| Information exchange subscale | |

| 1. Durante la consulta sobre métodos anticonceptivos, pude opinar sobre mis necesidades. During the contraception consultation, I was able to give my opinion about what I needed. |

3.5(0.6) |

| 2. Recibí información completa sobre mis opciones para el uso de métodos anticonceptivos. I received complete information about my options for contraceptive methods. |

3.5(0.7) |

| 3. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud supo explicar claramente los métodos anticonceptivos. The provider knew how to explain contraception clearly. |

3.4(0.7) |

| 4. Tuve la oportunidad de participar en la elección de un método anticonceptivo. I had the opportunity to participate in the selection of a method. |

3.6(0.6) |

| 5. Recibí información sobre cómo protegerme de una infección de transmisión sexual. I received information about how to protect myself from sexually transmitted infections. |

3.3(0.9) |

| 6. Me dijeron qué hacer si falla un método anticonceptivo (e.j., condón roto, olvido de pastilla, sentir el DIU mal colocado). I received information about what to do if a method fails (e.g., broken condom, forget a pill, feel an IUD is poorly placed). |

2.9(0.9) |

| 7. Pude entender las reacciones que podría tener mi cuerpo al usar un método anticonceptivo. I could understand how my body might react to using contraception. |

3.3(0.8) |

| 8. Pude entender cómo usar el método o los métodos anticonceptivos de los que hablamos. I could understand how to use the method(s) we talked about during the consultation. |

3.4(0.7) |

| 9. Recibí información sobre qué hacer si quisiera dejar de usar un método anticonceptivo. I received information about what to do if I wanted to stop using a method. |

3.2(0.8) |

| 10. Me explicaron qué hacer si tenía una reacción al método anticonceptivo (e.j., alergia, nauseas, cólicos, alteraciones en la menstruación).b

The provider explained to me what to do if I had a reaction to a method (e.g., allergies, nausea, pains, menstrual changes). |

3.1(0.9) |

| Interpersonal relationship subscale | |

| 11. Sentí que la información que proporcioné iba a quedar entre el/la prestadora de servicios de salud y yo. I felt the information I shared with the provider was going to stay between us. |

3.6(0.6) |

| 12. Sentí que el/la prestadora de servicios de salud me daba el tiempo necesario para explorar mis opciones sobre métodos anticonceptivos. The provider gave me the time I needed to consider the contraceptive options we discussed. |

3.5(0.6) |

| 13. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me brindó un trato amable durante la consulta sobre métodos anticonceptivos. The provider was friendly during the contraception consultation. |

3.7(0.6) |

| 14. Sentí que el/la prestadora de servicios de salud tenía conocimiento sobre los métodos anticonceptivos. I felt the health care provider had sufficient knowledge about contraceptive methods. |

3.7(0.5) |

| 15. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud se interesó por mi salud al platicar sobre métodos anticonceptivos. The provider showed interest in my health while we talked about contraception. |

3.5(0.6) |

| 16. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud se interesó por lo que yo opiné. The provider was interested in my opinions. |

3.5(0.6) |

| 17. Me sentí escuchada por el/la prestadora de servicios de salud. I felt listened to by the provider. |

3.6(0.6) |

| Disrespect and abuse subscale | |

| 18. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me insistió para usar el método anticonceptivo que él/ella quería. The provider pressured me to use the method they wanted me to use. |

3.9(0.6) |

| 19. Sentí que el/la prestadora de servicios de salud me atendió mal debido a que suele juzgar a las personas. I felt the provider treated me poorly because they tend to judge people. |

3.9(0.4) |

| 20. Sentí que me regañaban por mi edad. I felt scolded because of my age. |

3.9(0.6) |

| 21. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me hizo sentir incómoda por mi vida sexual (e.j., inicio de vida sexual, preferencia sexual, número de parejas, número de hijos). The provider made me feel uncomfortable because of my sex life (e.g., when I started having sex, my sexual preferences, the number of partners I have, the number of children I have). |

3.9(0.6) |

| 22. El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me observó o me tocó de una forma que me hizo sentir incómoda. The provider looked at me or touched me in a way that made me feel uncomfortable. |

4.0(0.3) |

| Items not retained in final scale c | |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me preguntó qué tipo de método quería usar. The health care provider asked me what type of method I would like to use. |

3.5(0.6) |

| Recibí información completa sobre los efectos que podrían tener en mi cuerpo los métodos anticonceptivos. I received complete information about effects that contraceptive methods could have on my body. |

3.3(0.8) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud y yo platicamos de acuerdo a mis necesidades lo bueno y lo malo de los métodos que revisamos. The provider and I considered the good and the bad of the methods we discussed, according to my needs. |

3.3(0.8) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud mostró interés por entenderme. The provider showed interest in understanding me. |

3.6(0.6) |

| Sentí que el/la prestadora de servicios de salud estaba dispuesto a contestar cualquier pregunta que yo le hiciera. I felt the health care provider was willing to answer any questions I might have had. |

3.6(0.6) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud consideró mi estado de salud. The health care provider considered my health status. |

3.6(0.6) |

| Sentí que estaba en un espacio donde otras personas no iban a escuchar la conversación con el/la prestadora de servicios de salud. I felt I was in a space where other people would not hear my conversation with the provider. |

3.4(0.8) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud ignoró lo que yo quería sobre los métodos anticonceptivos. The provider ignored what I wanted related to contraception. |

3.7(0.7) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me presionó a usar un método anticonceptivo para que no me embarazara. The provider pressured me to use a method so that I wouldn't get pregnant. |

3.9(0.5) |

| Hubo interrupciones de otras personas durante la consulta sobre métodos anticonceptivos. There were interruptions from another person during the contraception consultation. |

3.7(0.8) |

| Dentro de la unidad de salud, alguna persona que yo no quería que se enterara supo que solicité un método anticonceptivo. Someone I didn't want to know that I was talking about contraception found out while I was at the health care center. |

3.9(0.5) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud hizo comentarios inadecuados acerca de mí o de lo que yo dije. The provider made inappropriate comments about me or something I said. |

4.0(0.3) |

| El/la prestadora de servicios de salud me hizo sentir avergonzada durante la consulta sobre métodos anticonceptivos. The provider made me feel embarrassed during the consultation about contraception. |

3.9(0.4) |

Original Spanish wording given, followed by English translation. Items retained in final scale are numbered, and ordered by the factors identified in factor analysis (see Table 3). Higher scores equate with higher reported quality. Response categories for positively worded items were “completely agree/totalmente de acuerdo” (4), “agree/de acuerdo” (3), “disagree/en desacuerdo” (2), and “completely disagree/totalmente en desacuerdo” (1). Response categories for negatively worded items were “yes/sí” (1), “yes with doubts/sí con dudas” (2), “no with doubts/no con dudas” (3), and “no/no” (4). Missing data ranges from 0–6 cases per item, with the exception of item 4 (missing 47 cases), which had a “not applicable” option.

All items retained original wording from validation study, except this item where the word “abnormal” was removed before “reaction” for clarity's sake.

See Appendix for description of rationale for removing these items.

SD = Standard Deviation.

Scale Validation and Item Reduction

Response Rate

We conducted 242 exit interviews in Mexico City and 257 in San Luis Potosí (N = 499). We reached 60 percent (n = 207) of the 70 percent (n = 347) of women who agreed to be reached for phone follow‐up. The average number of days between baseline and follow‐up was 52 days (range=31–113 days; median=49 days); 74 percent were reached within the planned 30–60 day timeframe and 99 percent were reached within 90 days.

Participant and Visit Characteristics

Participant and visit characteristics, stratified by city, are displayed in Table 2. The average age was 26 years, and 63 percent dedicated themselves to housework or other unpaid work. There were significant differences between cities in terms of education status, with 48 percent in Mexico City compared to 34 percent in San Luis Potosí having more than a secondary school education. Women in Mexico City also had significantly fewer children on average, were less likely to be married, and were more likely to identify as LGBTTTIQ.2

Table 2.

Participant and visit characteristics, by state (N=499)

| Characteristic | Mexico City (n=242) | San Luis Potosí (n=257) | Combined | p‐valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD, range) | 26(8, 15–51) | 26(8, 15–50) | 26(8, 15–51) | 0.78 |

| Occupation, n(%) | ||||

| Household or other unpaid work | 150(62%) | 163(65%) | 313(63%) | 0.34 |

| Paid work | 63(26%) | 52(21%) | 115(23%) | |

| Student | 29(12%) | 36(14%) | 65(13%) | |

| Education status, n(%) | ||||

| More than secondary school | 116(48%) | 86(34%) | 202(41%) | 0.003 |

| Secondary school | 103(43%) | 127(50%) | 230(47%) | |

| Primary school or less | 22(9%) | 39(15%) | 61(12%) | |

| Number of children, mean (SD, range) | 1(1, 0–5) | 2(1, 0–5) | 1(1, 0–5) | 0.0002 |

| Marital status, n(%) | ||||

| In union | 123(51%) | 104(41%) | 227(46%) | <0.0001 |

| Single | 72(30%) | 52(21%) | 124(25%) | |

| Married | 9(16%) | 83(33%) | 122(25%) | |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 8(3%) | 12(5%) | 20(4%) | |

| Identifies as LGBTTTIQ, n(%) | 34(14%) | 7(3%) | 41(8%) | <0.0001 |

| Reason for visit, n(%) | ||||

| Request a contraceptive method | 65(27%) | 39(15%) | 104(21%) | <0.0001 |

| Ask for contraceptive information | 52(22%) | 22(9%) | 74(15%) | |

| Method follow‐up | 27(11%) | 69(27%) | 96(19%) | |

| Prenatal care | 35(15%) | 34(13%) | 69(14%) | |

| Method removal | 25(10%) | 18(7%) | 43(9%) | |

| Postpartum care | 20(8%) | 25(10%) | 45(9%) | |

| Otherb | 17(7%) | 48(19%) | 65(13%) | |

| Provider type, n(%) | ||||

| Doctor | 220(91%) | 138(54%) | 358(72%) | <0.0001 |

| Nurse | 13(5%) | 113(44%) | 126(25%) | |

| Otherc | 8(3%) | 5(2%) | 13(3%) | |

| Provider sex, n(%) | ||||

| Female | 160(66%) | 202(79%) | 362(73%) | 0.002 |

| Male | 81(34%) | 54(21%) | 135(27%) | |

| Clinical setting, n(%) | ||||

| Public clinic | 242(100%) | 232(90%) | 474(95%) | <0.0001 |

| Public hospital | 0(0%) | 25(10%) | 25(5%) | |

Continuous variables compared with two‐sided t‐tests; categorical variables compared with Pearson chi‐square tests. Missing data ranged from 0–8 cases per variable.

Other visit category includes primarily preventive checkups, as well as post‐abortion care or other specialty care in which contraception was discussed.

Other provider type category includes social workers, psychologists, and health promoters.

LGBTTTIQ = Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, transsexual, two‐spirited, intersexed, queer.

Around one‐third (36 percent) of participants had come seeking contraceptive information or new methods, 28 percent were consulting about or requesting removal of a method they were already using, and the remainder (36 percent) interacted with the provider about contraception in the context of prenatal, postpartum, preventive, or specialty care (Table 2). Almost three‐quarters were seen by a doctor (72 percent) and by a female provider (73 percent); 95 percent were seen in a public clinic setting versus a public hospital (5 percent). Significantly more participants in Mexico City than San Luis Potosí had come specifically seeking contraceptive information or new methods, were seen by a doctor, and were seen by a male provider. All of the participants recruited from hospitals were in San Luis Potosí.

Those reached for follow‐up calls did not differ significantly from those not reached by city or on any of the personal or provider characteristics displayed in Table 2 (data not shown).

Item Response Frequencies

Table 1 displays mean response on a scale of 1–4 (4 representing the highest quality experience) for each item in the original item pool, with both cities combined (averages between cities did not differ more than 0.2 for any item). Responses were skewed toward reporting higher‐quality counseling, with all but one item having a mean above 3.

Factor Analysis

The scree plot from the EFA for San Luis Potosí yielded three factors. We labeled the factors: 1) Information Exchange, 2) Interpersonal Relationship, and 3) Disrespect and Abuse. The Information Exchange factor includes items capturing the needs assessment and information provision aspects of the QCC Framework (e.g., soliciting client preferences and providing information about methods and how to manage side effects); the Interpersonal Relationship factor includes items that capture the relationship‐building elements of the QCC Framework—including privacy, confidentiality, trust, respect, empathy, and nondiscrimination; and the Disrespect and Abuse factor includes items probing for coercion or mistreatment by providers (Holt, Dehlendorf, and Langer 2017). The naming of the factors purposely builds on other frameworks in the international reproductive health field; namely, “Information Exchange” is the phrasing used in the updated framework for quality in family planning services (Jain and Hardee 2018), and “Disrespect and Abuse” comes from human rights frameworks to promote respectful care in childbirth (White Ribbon Alliance 2011). The specific wording of items in each factor was based on women's expressed preferences from the formative focus group study in Mexico (Holt et al. 2018).

Items and their dominant factor loading for the final scale are displayed in Table 3. All factor loadings from the initial EFA with the entire 35‐item pool are available in the Appendix.3 The large majority of items in the final scale loaded at least 0.50 on their dominant factor. Two items in the Information Exchange factor were retained despite lower loadings; both are critical from a content validity perspective because they are the two items that cover the aspect of information exchange that concerns patients having the opportunity to insert their own opinions and preferences into the discussion (Q1: “During the contraception consultation, I was able to give my opinion about what I needed,” and Q4: “I had the opportunity to participate in the selection of a method”) whereas the rest of the items in this factor cover information provided by providers. No items in the final scale loaded more than 0.3 on their nondominant factor (data not shown).

Table 3.

Final Quality of Contraceptive Counseling (QCC) Scale with results from factor analysis and Item Response Theory (IRT) Models, San Luis Potosí (SLP) and Mexico City (DF) (N=499)a

| SLP IRT parameters | DF IRT parameters | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLP EFAb factor loading | DF CFAb factor loading | Discrim‐ination | Difficulty, 2 of 4 score | Difficulty, 3 of 4 score | Difficulty, 4 of 4 score | Discrim‐ination | Difficulty, 2 of 4 score | Difficulty, 3 of 4 score | Difficulty, 4 of 4 score | |

| Information exchange factor alpha=0.89 (same in both states) | ||||||||||

| 1. During the contraception consultation, I was able to give my opinion about what I needed. | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.7 | −3.9 | −2.0 | −0.2 | 2.0 | −3.6 | −1.9 | −0.3 |

| 2. I received complete information about my options for contraceptive methods. | 0.6 | 0.7 | 2.3 | −3.4 | −1.7 | −0.4 | 2.8 | −2.6 | −1.3 | −0.3 |

| 3. The provider knew how to explain contraception clearly. | 0.6 | 0.8 | 2.9 | −2.9 | −1.5 | −0.3 | 2.5 | −2.3 | −1.5 | −0.1 |

| 4. I had the opportunity to participate in the selection of a method. | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.8 | −3.7 | −2.2 | −0.6 | 2.0 | −3.4 | −1.8 | −0.3 |

| 5. I received information about how to protect myself from sexually transmitted infections. | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.7 | −2.7 | −1.3 | −0.3 | 1.3 | −3.0 | −1.2 | 0.1 |

| 6. I received information about what to do if a method fails (e.g., broken condom, forget a pill, feel an IUD is poorly placed). | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.3 | −3.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | −2.2 | −0.6 | 0.5 |

| 7. I could understand how my body might react to using contraception. | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.7 | −3.0 | −1.5 | −0.1 | 2.5 | −2.5 | −1.1 | −0.1 |

| 8. I could understand how to use the method(s) we talked about during the consultation. | 0.6 | 0.8 | 2.8 | −2.8 | −1.5 | −0.3 | 2.6 | −2.5 | −1.5 | −0.1 |

| 9. I received information about what to do if I wanted to stop using a method. | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.8 | −2.7 | −1.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 | −2.7 | −1.1 | 0.3 |

| 10. The provider explained to me what to do if I had a reaction to a method (e.g., allergies, nausea, pains, menstrual changes).c | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.8 | −2.9 | −0.9 | 0.2 | 2.2 | −2.3 | −0.8 | 0.1 |

| Interpersonal relationship factor alpha=0.91 (0.92 in SLP, 0.91 in DF) | ||||||||||

| 11. I felt the information I shared with the provider was going to stay between us. | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | d | −2.7 | −0.6 | 1.5 | −4.3 | −2.8 | −0.5 |

| 12. The provider gave me the time I needed to consider the contraceptive options we discussed. | 0.5 | 0.8 | 3.9 | −2.7 | −1.4 | −0.3 | 3.8 | −2.3 | −1.7 | −0.3 |

| 13. The provider was friendly during the contraception consultation. | 0.8 | 0.8 | 3.7 | −2.5 | −2.2 | −0.6 | 3.8 | −2.7 | −2.0 | −0.6 |

| 14. I felt the health care provider had sufficient knowledge about contraceptive methods. | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.7 | −2.8 | −2.1 | −0.6 | 3.8 | −2.7 | −1.9 | −0.5 |

| 15. The provider showed interest in my health while we talked about contraception. | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.7 | −2.9 | −1.8 | −0.4 | 3.3 | −2.6 | −1.6 | −0.3 |

| 16. The provider was interested in my opinions. | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.8 | −2.9 | −1.9 | −0.3 | 4.1 | −2.4 | −1.9 | −0.3 |

| 17. I felt listened to by the provider. | 0.7 | 0.8 | 3.9 | −2.7 | −1.9 | −0.4 | 3.6 | d | −1.9 | −0.4 |

| Disrespect and abuse factor alpha=0.76 (0.76 in SLP, 0.75 in DF) | ||||||||||

| 18. The provider pressured me to use the method they wanted me to use. | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | −4.6 | −4.1 | −3.8 | 1.6 | −3.4 | −2.6 | −2.3 |

| 19. I felt the provider treated me poorly because they tend to judge people. | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.6 | −3.7 | −3.1 | −2.5 | 3.2 | −2.4 | −2.2 | −1.9 |

| 20. I felt scolded because of my age. | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | −4.6 | −4.3 | −3.6 | 1.0 | −3.6 | −3.3 | −3.1 |

| 21. The provider made me feel uncomfortable because of my sex life (e.g., when I started having sex, my sexual preferences, the number of partners I have, the number of children I have). | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.6 | −2.9 | −2.7 | −2.4 | 3.3 | −2.0 | −1.8 | −1.7 |

| 22. The provider looked at me or touched me in a way that made me feel uncomfortable. | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.1 | −3.3 | −2.9 | −2.6 | 1.8 | −3.4 | −3.1 | −2.9 |

| Overall alpha=0.92 (same in both states). | ||||||||||

| Overall correlation between subscores: Information x Relationship = 0.7; Information x Disrespect = 0.3; Relationship x Disrespect = 0.4. | ||||||||||

Higher scores equate with higher reported quality. Response categories for positively worded items were “completely agree/totalmente de acuerdo” (4), “agree/de acuerdo” (3), “disagree/en desacuerdo” (2), and “completely disagree/totalmente en desacuerdo” (1). Response categories for negatively worded items were “yes/sí” (1), “yes with doubts/sí con dudas” (2), “no with doubts/no con dudas” (3), and “no/no” (4). Amount of nonresponse ranged from 1−6 per item for all but item 4 in which individuals were given a “not applicable” option and 47 individuals did not respond. Original Spanish wording is in Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) performed with SLP data; confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) performed on DF data after reduction of item pool.

All items retained original wording from validation study, except this item where the word “abnormal” was removed before “reaction” for clarity's sake.

IRT model unable to produce difficulty parameter for this category boundary.

CFA revealed that the data from Mexico City fit well with the factor structure identified in San Luis Potosí, with all but one item loading at least 0.5 onto its assigned factor (Table 3). The item that loaded at 0.3 on the Disrespect and Abuse scale in Mexico City was: “The provider looked at me or touched me in a way that made me feel uncomfortable.” This suggests that in Mexico City, experience of being looked at or touched inappropriately did not co‐occur with other forms of disrespect and abuse to the degree to which it had in San Luis Potosí where the factor loading for this item was higher (0.8). The lack of consistency in how the item performed between geographies for this item is tolerable from the standpoint of content validity; in other words, capturing any instances of disrespect and abuse (particularly this one which the formative focus group study indicated was a common concern among contraception clients [Holt et al. 2018] and cognitive interviews confirmed was salient and understandable) is critical to measuring client experience regardless of whether different forms co‐occur in the same way in different geographies. The factor loading of 0.3 in Mexico City indicated some degree of consistency, if lower than the threshold we aimed for.

Correlations between computed subscale scores were acceptable for considering the latent construct unidimensional for purposes of IRT analyses and composite score construction. Information Exchange and Interpersonal Relationship subscales (representing 17 of 22 items) were highly correlated (Pearson coefficient=0.7) in analyses combining data from the two states (Table 3). The Disrespect and Abuse subscale correlated 0.3 with Information Exchange and 0.4 with Interpersonal Relationship.

Item Response Theory

The 2‐parameter graded response model yielded the difficulty and discrimination parameters displayed in Table 3 (results from the initial analysis with the full item pool are in the Appendix). Difficulty parameters (a relative measure of how positive an experience would have to be for an individual to rate their experience on an item as one step higher on the scale of 1–4) were very low overall, ranging from –4.6 to 0.7, given the overall high levels of quality reported by participants. Difficulty parameters showed the least spread for items in the Disrespect and Abuse factor, given the higher average item responses in that set. Discrimination parameters were high overall, indicating items are able to distinguish well between different latent quality levels. Several, particularly within the Interpersonal Relationship factor, exceeded the typical range of zero to two (Harris 1989), reaching values over four.

Item Reduction

Taken together, the results of the EFA and IRT, combined with considerations of content validity, led us to remove the 13 items shown at the bottom of Table 1. A description of the rationale for removing each of these items is in the Appendix.

Test Information Functions generated from combined‐state IRT models run on full versus reduced item pools (data not shown) demonstrate that, despite the expected decrease in precision that is standard when reducing the number of items in a scale, the pattern of information provided along the full spectrum of underlying quality levels (“thetas” in IRT) is similar (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Test Information Functions from Item Response Theory models before and after item reduction

Reliability

Cronbach's alpha for the entire 22‐item QCC Scale was 0.92 in both states (Table 3). Alphas for Information Exchange and Interpersonal Relationship factors were similar (0.89 and 0.91, respectively) while alpha for Disrespect and Abuse was lower though still acceptable, particularly for a short five‐item subscale (0.76).

Scale Scores

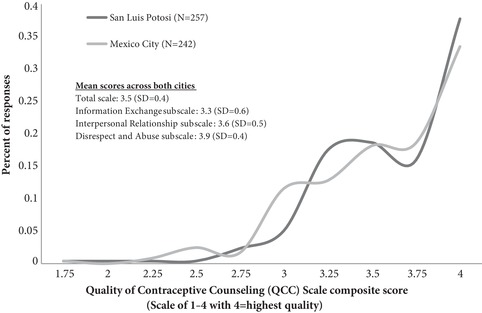

The distribution of QCC Scale scores by state (calculated as a mean score across the 22 items), and mean subscale scores, are presented in Figure 3. Skew of QCC total scores was acceptable (–1.2 in SLP and –1.1 in Mexico City) indicating the appropriateness of retaining the 4‐point response scale for composite scores. The Disrespect and Abuse subscale was highly skewed (–4.1), suggesting that as a standalone measure of disrespect and abuse in family planning care, responses should be dichotomized to report of anything less than the highest score versus all other responses.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Quality of Contraceptive Counseling Scale composite and subscale scores, Mexico City and San Luis Potosí (N=499)

Correlational Validity

QCC total scale scores were highly correlated with the binary overall measure of patient experience, collapsed from four categories due to low number of negative responses (OR=22.6, 95% CI: 10.9–46.8) (Table 4). Among participants who had selected a method after their interaction with a provider about contraception, there was also high correlation between QCC Scale scores and their reported intention to initiate use of the method (OR=4.2, 95% CI: 2.2–7.9). Subscale scores were also significantly correlated with both of these convergent validity variables.

Table 4.

Correlational validity by Quality of Contraceptive Counseling (QCC) Scale domain: Results from logistic regression analysis, Mexico City and San Luis Potosía

| External variable | n(%) | Information Score OR (95% CI) p‐value | Relationship Score OR (95% CI) p‐value | Disrespect Scoreb OR (95% CI) p‐value | Total Score OR (95% CI) p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convergent validity variables | |||||

| Highest rating of overall experience with provider (n=496)c | 250(50.4) | 5.7(3.6–8.8) p<0.0001 |

10.8(6.3–18.5) p<0.0001 |

1.4(1.3–1.7) p<0.0001 |

22.6(10.9–46.8) p<0.0001 |

| Intention to use method selected at baseline (n=395)d | 361(91.4) | 2.6(1.5–4.4) p=0.001 |

2.6(1.5–4.6) p=0.001 |

1.3(1.0–1.6) p=0.03 |

4.2(2.2–7.9) <p=0.0001 |

| Predictive validity variables | |||||

| Use of contraception at 1–3 months follow‐up (n=169)e | 135(79.9) | 1.8(0.8–4.0) p=0.1 |

3.2(1.1–9.4) p=0.03 |

1.0(0.7–1.4) p=0.9 |

2.6(0.9–7.5) p=0.07 |

| Informational needs met at 1–3 months follow‐up (n=205)c | 148(72.2) | 2.6(1.4–4.9) p=0.003 |

3.9(2.1–7.4) p<0.0001 |

1.1(0.9–1.3) p=0.5 |

4.7(2.0–10.8) p<0.0001 |

| Divergent validity variable | |||||

| Highest rating of waiting room (n=494)c | 392(79.4) | 0.9(0.6–1.4) p=0.7 |

0.8(0.5–1.5) p=0.6 |

0.9(0.8–1.1) p=0.4 |

0.9(0.5–1.6) p=0.6 |

Odds ratios are from bivariate logistic regression models estimating the odds of each dichotomous external variable associated with a one‐unit increase in QCC Scale Scores, accounting for clustering by provider through use of robust standard errors in complete case analysis. We conducted sensitivity analyses without use of robust standard errors to allow for inclusion of 41 additional cases where the provider was not known; these analyses revealed similar findings, with the exception of the relationship between the disrespect score and intention to use the selected method which had a similar OR but was no longer significant (p=0.08) (data not shown). In models for predictive validity variables, we ran sensitivity analyses controlling for amount of time since follow‐up and results were unchanged (data not shown).

Disrespect and Abuse score dichotomized into highest score (higher=better quality) versus all else, due to high skew.

Missing data ranged from 2–5 cases for these variables.

This variable was assessed only among participants reporting they selected a method (94 participants indicated not having selected a method at baseline); an additional 10 cases were missing.

Seven participants who reported not wanting to prevent pregnancy and 30 who reported being pregnant at baseline were dropped from this analysis; one additional case was missing data.

QCC total scale scores were significantly associated with reporting informational needs being met at 1–3 months follow‐up (OR=4.7, 95% CI: 2.0–10.8), and use of contraception, with borderline statistical significance (OR=2.6, 95% CI: 0.9–7.5) (Table 4). Subscale scores for Information Exchange and Interpersonal Relationship domains, but not Disrespect and Abuse, followed a similar pattern of significant or borderline significant associations with these predictive validity variables (Table 4). Those reached for follow‐up calls did not differ significantly from those not reached on overall scores or subscores (data not shown).

QCC total scale scores were not associated with a dichotomous measure of patients’ perceptions of the waiting room (OR=0.9, 95% CI: 0.5–1.6) and nor were subscale scores (Table 4), providing support for divergent validity.

In analyses by city, the above trends held with a similar pattern of results, though did not always reach statistical significance likely due to relatively smaller sample size (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The QCC Scale, constructed with data from San Luis Potosí, Mexico includes 22 items and consists of three underlying dimensions: Information Exchange, Interpersonal Relationship, and Disrespect and Abuse. These dimensions were reproduced in analyses of how items related to each other in the separate sample from Mexico City. The original pool of 35 items was reduced by triangulating findings from quantitative analyses examining item distributions and properties and how items related to each other, while ultimately prioritizing content validity (i.e., making sure the full range of the QCC construct was covered).

The Information Exchange dimension includes information provided to women about contraceptive method options and follow‐up, as well as the information they share with providers about preferences and needs. The Interpersonal Relationship dimension encompasses items related to privacy, confidentiality, respect, trust, and empathy. The Disrespect and Abuse dimension includes extreme negative treatment of women by providers in the form of coercion to use a contraceptive method, discrimination, and physical abuse. These dimensions align with the QCC measurement framework, which includes both specific elements of the counseling process as well as foundational relationship‐building elements drawn from the health communication and human rights literatures (Holt, Dehlendorf, and Langer 2017). The dimensions were sufficiently correlated with each other to allow for creating an overall score comprising the average of all 22 items. Each subscale score can also stand alone as a measure of the separate subconstructs of Information Exchange, Interpersonal Relationships, or Disrespect and Abuse (as discussed, we recommend Disrespect and Abuse scores be dichotomized when used as stand‐alone measures due to high skew).

The robust measurement of client experience afforded by the QCC Scale can be used to guide systemic quality improvement efforts in health care systems and facilities. Composite scores allow for a comprehensive look at women's experiences with contraception providers and examination of trends over time or between groups (e.g., by age or between returning versus new users). Subscale scores and individual item scores allow for homing in on specific dimensions of women's experiences to identify actionable areas for improvement. In particular, the Disrespect and Abuse subscale may be useful as an accountability mechanism to ensure voluntarism and lack of abuse in settings where there is buy‐in for monitoring for negative experiences. Calls have been made for more measurement of negative experiences and protection of voluntarism in family planning programs in general (Harris, Reichenbach, and Hardee 2016), and specifically in performance‐based incentive programs due to the potential for perverse incentives affecting provider behavior (Eichler et al. 2010; Askew and Brady 2013). The QCC Scale can contribute to helping programs proactively identify and address poor quality of care and rights violations. Approaching such efforts in a nonpunitive fashion may best promote buy‐in from providers and administrators who may be sensitive to possible implications of their clients reporting negative experiences (Harris, Reichenbach, and Hardee 2016). Though the QCC Scale was designed primarily to be a tool for facilities and systems to internally monitor quality through exit interviews with clients, its potential as a tool for social accountability or mystery client studies could also be assessed.

QCC scores can also be used for research purposes to investigate, on the one hand, the determinants of positive client experiences with contraceptive care and, on the other hand, the impact of positive experiences on health, well‐being, and health‐care seeking. More longitudinal research is needed to better understand contraceptive use dynamics as well as the impacts of high‐quality counseling, and the QCC Scale provides a tool to facilitate such research. We found that better quality, as measured by the QCC Scale, was correlated with women's ability to identify and use methods that would meet their needs.

Two other new measures, both developed in other countries during time periods overlapping that of the QCC Scale, have recently been published. This speaks to the many current global efforts underway to improve measurement of quality in family planning services. The 11‐item Interpersonal Quality of Family Planning (IQFP) Scale was developed in the United States among women in the San Francisco Bay Area (Dehlendorf et al. 2018). Though there is some overlap in the construct the IQFP Scale was designed to measure (patient‐centeredness in contraceptive counseling), the IQFP Scale does not include questions related to human rights constructs of privacy, confidentiality, or nondiscrimination, and does not include questions probing for negative experiences such as coercion or sexual harassment. The QCC Scale in its current form is twice as long as the IQFP Scale, which has advantages in terms of covering the full range of the construct and disadvantages in terms of administration time. Another new scale developed concurrently with the QCC Scale in India (22 items) and Kenya (20 items) was recently published: the Person‐Centered Family Planning (PCFP) Scale (Sudhinaraset et al. 2018). This measure captures a broader construct than the IQFP and QCC Scales, as it is focused not only on patient‐provider communication, but other aspects of the health facility environment relevant to patient centeredness. It also differs from the IQFP and QCC Scales in that items were generated based on a desk review of existing measures rather than focus groups or interviews with local contraception clients.

The development of the QCC Scale in Mexico should be considered in light of several limitations. First, the Test Information Functions from the IRT models suggest that the QCC Scale provides the most information for individuals with lower levels of quality than reported on average in this study (interquartile range of average thetas was –0.7 to 0.7 [data not shown] whereas the Test Information Functions in Figure 2 mostly cover a range of scores lower than this). This is not surprising, given that experience scores are known to suffer commonly from skew toward higher quality, due in part to social desirability bias as well as expectations for care that are sometimes low. Further, due to loss to follow‐up, our analyses of the correlation between QCC Scale scores and contraceptive use and informational needs at follow‐up were underpowered to detect potentially meaningful differences. Additionally, a quarter of those who participated in the follow‐up interview were reached outside of the planned 60‐day timeframe (although the responses of those reached for follow‐up within the target 60‐day time period did not differ from the responses of those reached outside the planned time period in terms of reported use of contraception or informational needs being met in Chi Square analyses (data not shown), suggesting this did not have an impact on our ability to capture the association between QCC Scale scores and these short‐term outcomes). Future work should be undertaken to examine the impact of experience with contraceptive counseling on women's health, health‐care seeking, and lives.

A strength of this study is that the QCC Scale validation results from San Luis Potosí were reproduced in Mexico City, where participants represented a less conservative and more educated population, with a lower fertility rate. This suggests that the scale was effectively designed to be applicable to diverse populations. In terms of the generalizability of our findings, it is worth noting some important limitations: 1) our recruitment strategy did not reach women living in remote areas or indigenous women unable to speak Spanish and therefore the extent to which the findings are generalizable to these populations within Mexico is unknown and should be further investigated; 2) although 5 percent of our overall sample was recruited in hospitals, the sample size was not large enough to examine differences in scale performance between postpartum and other women; and 3) the extent to which the QCC Scale would be valid in other countries is not clear. We intend to test versions of the QCC Scale adapted for other settings, and to identify a short form valid for use in cross‐country comparisons.

CONCLUSIONS

The QCC Scale was found to be valid and reliable for use in measuring women's experiences with contraceptive counseling in Mexico. The three related dimensions of the scale—Information Exchange, Interpersonal Relationship, and Disrespect and Abuse—cover a broader construct than is typically captured in survey instruments capturing client experience with contraceptive care; thus, the scale provides a useful tool for more comprehensively measuring quality and rights in women's interactions with providers of contraception. QCC total scores and subscale scores can be used to bolster contraceptive counseling improvement efforts in Mexico, and their validity for use in other countries should be assessed.

Supporting information

Appendix

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Ana Gabriela Torres Canseco and Doroteo Mendoza Victorino for providing input on the study design, and María Luisa Ledesma Ibarra in providing technical support for data collection. We would also like to thank all of the individuals who contributed to data collection: Anabel López San Martin, Ana Lilia Espericueta Hernández, Edalit Alcántara Pérez, Estefani Ernestina Herrera Aguirre, Miriam Estefanía Alemán Sifuentes, Teresa Guadalupe Navarro Menchaca, Xóchitl Guzmán Delgado, Patricia Cala Barranco, Maria Solemn Dominguez Resendis, and Karla Ivone Ramírez Martínez. Finally, we would like to express deep gratitude to the women who participated in the study, and the health system leadership and clinic and hospital directors who gave us permission to recruit their patients for this study. This project was supported by a grant from the David & Lucile Packard Foundation.

Kelsey Holt is Assistant Professor and Danielle Hessler is Associate Professor, University of California, San Francisco, 1001 Potrero Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94110. Email: Kelsey.Holt@ucsf.edu. Icela Zavala is Evaluation Manager and Ximena Quintero is Research Assistant, Mexican Family Planning Association, Mexico City, Mexico. Ana Langer is Professor, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Footnotes

We refer to Mexico City and San Luis Potosí as states for ease of language, but Mexico City is a federal entity and San Luis Potosí is a state.

LGBTTTIQ stands for “Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, transsexual, two‐spirited, intersexed, queer.” Original Spanish wording for this question was: “¿Se identifica como parte de la comunidad de la diversidad sexual (LGBTTTIQ)?”

The Appendix is available at the supporting information tab at wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/sfp.

REFERENCES

- Abdel‐Tawab, Nahla and RamaRao Saumya. 2010. “Do improvements in client‐provider interaction increase contraceptive continuation? Unraveling the puzzle,” Patient Education and Counseling 81(3): 381–387. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends‐Kuenning, Mary and Kessy Flora L.. 2007. “The impact of demand factors, quality of care and access to facilities on contraceptive use in Tanzania,” Journal of Biosocial Sciences 39(1): 1–26. 10.1017/s0021932005001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew, Ian and Brady Martha. 2013. Reviewing the evidence and identifying gaps in family planning research: The unfinished agenda to meet FP2020 goals. In background document for the Family Planning Research Donor Meeting, Washington, DC, 3–4 December 2012. New York: Population Council. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, Ann K. , Curtis Siân L., and Croft Trevor N.. 2002. “Monitoring contraceptive continuation: Links to fertility outcomes and quality of care,” Studies in Family Planning 33 (2): 127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Judith . 1990. “Fundamental elements of the quality of care: A simple framework,” Studies in Family Planning 21(2): 61–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto De Cetina, Thelma E. , Canto Patricia, and Ordonez Luna Manuel. 2001. “Effect of counseling to improve compliance in Mexican women receiving depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate,” Contraception 63(3): 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, Raymond B. 1966. “The scree test for the number of factors,” Multivariate Behavioral Research 1(2): 245–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Código Penal para el Distrito Federal . 2017. Federal District Official Gazette (Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal) . Updated: 22 December 2017.

- Código Penal del Estado de San Luis Potosí . 2018. Official Newspaper (Periódico Oficial) . Updated: 27 July 2018.

- Darney, Blair G. , Saavedra‐Avendano Biani, Sosa‐Rubi Sandra G., Lozano Rafael, and Rodriguez Maria I.. 2016. “Comparison of family‐planning service quality reported by adolescents and young adult women in Mexico,” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 134(1): 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlendorf, Christine , Henderson Jillian T., Vittinghoff Eric, Steinauer Jody, and Hessler Danielle. 2018. “Development of a patient‐reported measure of the interpersonal quality of family planning care,” Contraception 97(1): 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, Robert F. 2011. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Vol. 26 Los Angeles, California: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, Rena , Seligman Barbara, Beith Alix, and Wright Jenna. 2010. “Performance‐Based Incentives: Ensuring Voluntarism in Family Planning Initiatives.” Report. Bethesda, MD: Health Systems 20/20 project, Abt Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Hardee, Karen , Newman Karen, Bakamjian Lynn, Kumar Jan, Harris Shannon, Rodríguez Mariela, and Willson Kay. 2013. Voluntary Family Planning Programs That Respect, Protect, and Fulfill Human Rights: A Conceptual Framework Washington, DC: Futures Group. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Deborah . 1989. “Comparison of 1‐, 2‐, and 3‐Parameter IRT Models,” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 8(1): 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Shannon , Reichenbach Laura, and Hardee Karen. 2016. “Measuring and monitoring quality of care in family planning: Are we ignoring negative experiences?" Open Access Journal of Contraception 7: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Kelsey , Caglia Jacquelyn M., Peca Emily, Sherry James M., and Langer Ana. 2017. “A call for collaboration on respectful, person‐centered health care in family planning and maternal health,” Reproductive Health 14(1): 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Kelsey , Dehlendorf Christine, and Langer Ana. 2017b. “Defining quality in contraceptive counseling to improve measurement of individuals' experiences and enable service delivery improvement,” Contraception 96(3): 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Kelsey , Zavala Icela, Quintero Ximena, et al. 2018. “Women's preferences for contraceptive counseling in Mexico: Results from a focus group study,” Reproductive Health 15(1): 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) . 2013. Getting to Know the Federal District/Getting to Know San Luis Potosí (Conociendo el Distrito Federal/Conociendo San Luis Potosí). México: INEGI. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) . 2016. Encuesta Intercensal 2015. Sociodemographic Panorama of Mexico City/ San Luis Potosí (Panorama Sociodemográficos de Ciudad de México/San Luis Potosí). México: INEGI. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Anrudh , Bruce Judith, and Kumar Sushil. 1992. “Quality of services programme efforts and fertility reduction,” in Phillips James F. and Ross John A. (eds.), Family Planning Programmes and Fertility. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, pp. 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Anrudh , Bruce Judith, and Mensch Barbara. 1992. “Setting standards of quality in family planning programs,” Studies in Family Planning 23(6): 392–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Anrudh K. and Hardee Karen. 2018. “Revising the FP Quality of Care Framework in the context of rights‐based family planning,” Studies in Family Planning 49(2): 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Anrudh K. , RamaRao Saumya, Kim Jacqueline, and Costello Marilou. 2012. “Evaluation of an intervention to improve quality of care in family planning programme in the Philippines,” Journal of Biosocial Science 44(1): 27–41. 10.1017/s0021932011000460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Michael A. , Hossain Mian Bazle, and Whittaker Maxine. 1997. “The influence of quality of care upon contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh,” Studies in Family Planning 28(4): 278–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Michael Alan , Ahmed Saifuddin, and Hossain Mian Bazle. 2003. The impact of quality of care on contraceptive use: Evidence from longitudinal data from rural Bangladesh. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, Population Council.

- Kruk, Margaret E. , Gage Anna D., Arsenault Catherine, et al. 2018. “High‐quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution,” The Lancet Global Health Commission 6(11): e1196–e1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Zhen‐Wu , Wu Shang Chun, Garceau Roger J., et al. 1996. “Effect of pretreatment counseling on discontinuation rates in Chinese women given depo‐medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception,” Contraception 53(6): 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch, Barbara , Arends‐Kuenning Mary, and Jain Anrudh. 1996. “The impact of the quality of family planning services on contraceptive use in Peru,” Studies in Family Planning 27(2): 59–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Robert , Fisher Andrew, Miller Kate, et al. 1997. “The situation analysis approach to assessing family planning and reproductive health services: A handbook." Africa Operations Research and Technical Assistance Project II: Population Council.

- Mroz, Thomas A. , Bollen Kenneth A., Speizer Ilene S., and Mancini Dominic J.. 1999. “Quality, accessibility, and contraceptive use in rural Tanzania,” Demography 36(1): 23–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Programa Sectoral de Salud . 2014. Specific Plan of Action: Family Planning and Contraception (Programa de Acción Específico: Planificación Familiar y Anticoncepción) 2013–2018.

- RamaRao, Saumya , Lacuesta Marlina, Costello Marilou, Pangolibay Blesilda, and Jones Heidi. 2003. “The link between quality of care and contraceptive use,” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 29(2): 76–83. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.076.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RamaRao, Saumya and Mohanam Raji. 2003. “The quality of family planning programs: Concepts, measurements, interventions, and effects,” Studies in Family Planning 34(4): 227–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sando, David , Abuya Timothy, Asefa Anteneh, et al. 2017. “Methods used in prevalence studies of disrespect and abuse during facility based childbirth: Lessons learned,” Reproductive Health 14(1): 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhinaraset, May , Afulani Patience A., Diamond‐Smith Nadia, Golub Ginger, and Srivastava Aradhana. 2018. “Development of a Person‐Centered Family Planning Scale in India and Kenya,” Studies in Family Planning 49(3): 237–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Tara and Bertrand Jane. 2001. Monitoring quality of care in family planning programs by the quick investigation of quality (QIQ): Country reports. MEASURE Evaluation Technical Report. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center. [Google Scholar]

- White Ribbon Alliance . 2011. “Respectful maternity care: The universal rights of childbearing women." Washington, DC: White Ribbon Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . 2014. “Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations.” Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix