Abstract

Background

Since the early ‘80s, the pulsed dye laser has been the standard treatment tool for non‐invasive port wine stain (PWS) removal. In the last three decades, a considerable amount of research has been conducted to improve clinical outcomes, given that a fraction of PWS patients proved recalcitrant to laser treatment. Whether this research actually led to increased therapeutic efficacy has not been systematically investigated.

Objective

To analyse therapeutic efficacy in PWS patients globally from 1986 to date.

Methods

PubMed was searched for all available PWS trials. Studies with a quartile percentage improvement scale were included, analysed and plotted chronologically. Treatment and patient characteristics were extracted. A mean clearance per study was calculated and plotted. A 5‐study simple moving average was co‐plotted to portray the trend in mean clearance over time. The data were separately analysed for multiple treatment sessions in previously untreated patients.

Results

Sixty‐five studies were included (24.3% of eligible studies) comprising 6207 PWS patients. Of all patients, 21% achieved 75–100% clearance. Although a few studies reported remarkably good outcomes in a subset of carefully selected patients, there was no upward trend over time in mean clearance.

Conclusion

The efficacy of PWS therapy has not improved in the past decades, despite numerous technical innovations and pharmacological interventions. With an unwavering patient demand for better outcomes, the need for development and implementation of novel therapeutic strategies to clear all PWS is as valid today as it was 30 years ago.

Introduction

The introduction of the pulsed dye laser (PDL) in the early ‘80s revolutionized the treatment of port wine stains (PWS) in terms of safety and efficacy. Subsequent clinical trials, however, revealed that the underlying principle of PDL therapy – selective photothermolysis (SP) – was itself selective for patients with a certain dermal vascular phenotype. As a result, a substantial fraction of the PWS population still suffered from suboptimal therapeutic outcomes. The years of intense research that followed to further improve SP and clinical outcomes yielded new PDL systems with longer wavelengths (585 and 595 nm), longer pulse durations, epidermal cooling modalities, different SP light sources and novel approaches altogether such as photodynamic therapy (PDT), pharmacological interventions and combination treatments.1, 2

In 2012, we published a comprehensive summary of clinical results, which spawned the narrative that therapeutic efficacy had not improved despite the multitude of innovations in the field.1 In this article, we revisited that narrative and reanalysed the clinical outcomes obtained to date in greater detail, also including trial results achieved with more modern modalities. The overall conclusion has not changed in the last 6 years: the efficacy of clinically offered PWS treatment modalities has not improved and approximately half of all PWS patients bear lesions that are recalcitrant to the different forms of treatment. This is disconcerting given the fact that research into novel therapeutic avenues has abated, in part driven by a shift to different, commercially more lucrative applications of biomedical lasers, while the patients’ need for more effective interventions has not.3

Methods

Advances in therapeutic efficacy were studied by comparing the results of published clinical trials in a chronological context. PubMed was searched for full‐text PWS intervention studies from 1986 (when the first clinical studies with PDL for PWS appeared) to date. No restrictions were applied on the types of studies and, where possible, non‐English studies were translated. To enable comparative analysis, only studies that employed the most common physician/investigator‐reported outcome scoring system were included, that is, those that classified results in quartiles of percentage lightening (i.e. 0–24%, 25–49%, 50–74% and 75–100%). Studies that reported an exact percentage clearance per patient (0–100%) or used other classes of percentage clearance that could be converted to the aforementioned quartiles were also included. Many other studies classified outcomes into ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’ and ‘excellent’, but the exact definitions for these classes vary widely and studies using non‐compliant scoring systems were excluded.4 Studies and treatment arms with less than five PWS patients were excluded. ‘Treatment arm’ refers to a patient cohort where one particular treatment modality was used. For example, a study comparing 577‐nm PDL to 585‐nm PDL comprised two treatment arms. In studies that compared different settings (e.g. pulse duration, fluence) within one laser system, only the treatment arm with the highest efficacy was included. Information on the study population, type of intervention(s) and lesion characteristics was extracted. Different treatment arms within one study were analysed separately.

In the first analysis, all included studies were clustered to paint a complete picture of PWS treatment outcomes over time. Inasmuch as the first analysis revealed no improvement in treatment outcomes over time, a second analysis was performed where studies were filtered based on prospective vs. retrospective trials, single vs. multiple treatment sessions and history of previous treatment vs. untreated PWS. The second analysis was performed to assess treatment outcome progress in better‐matched patient cohorts, thereby eliminating the possibility that clinical variables potentially responsible for deterring improvement in treatment outcomes would statistically affect those variables that did not, and thus falsely skew progress data. Studies in which less than 10% of patients had received previous treatment were sorted into the ‘untreated’ group for purposes of simplifying the analysis. In the group of ‘multiple treatment’ studies, patients were offered more than one treatment session.

In addition to analysing the stratified outcomes of individual treatment arms, the overall result per outcome category of all studies was calculated (i.e. for all included patients per category). To this end, a mean score that represents the result of the entire study population (H) was calculated per outcome category using Eqn (1),

| (1) |

where j is the number of subjects in the selected (quartile) category (extracted from all studies), and k is the total number of subjects in all studies. The stratified outcomes of individual treatment arms, filtered treatment arms and overall result per outcome category of all studies were plotted in bar charts.

To graphically monitor and compare overall study outcomes in chronological order, a mean clearance score per study or treatment arm () was calculated in the third analysis using Eqn (2),

| (2) |

where d, e, f and g represent the percentage of patients with 0–24%, 25–49%, 50–74% and 75–100% clearance, respectively. The values for d, e, f and g were extracted (or calculated if possible where not reported) from the included studies. Note that, as a corollary of this mathematical method, the minimum and maximum values for are 12.5% and 87.5%, respectively.

Finally, it was hypothesized that all the compounding research would lead to a gradual, non‐incidental improvement in clinical outcomes over time, and that this would be reflected by an increasing with the number of studies published. Accordingly, a five‐study/treatment arm simple moving average for clearance () was calculated in the fourth analysis by averaging the of a study in the chronological sequence of studies (n) and the mean clearance scores of its four preceding studies (n‐1, n‐2, n‐3, n‐4), according to Eqn (3).

| (3) |

The principle of the simple moving average was borrowed from the technical analysis of financial markets, where simple moving averages are employed to gauge trends in stock prices by filtering out the noise in momentary price fluctuations.5 The number of studies/treatment arms included in the moving average was set to five as this number was determined to be sufficiently high to offset volatility due to incidental outliers but not too high to obscure actual treatment improvement trends. The and were plotted in a line graph.

All plotted variables were evaluated for trends using visual inspection first. If an upward trend was asserted, regression analysis (Theil‐Sen estimator for non‐parametric data) and Spearman correlation analysis were performed.

Results

The global clinical reality in the face of 30 years of technological innovations

Our search resulted in 931 PubMed records published since 1986. After screening, studies were excluded because of the use of non‐compliant outcome scoring systems (N = 132), insufficient reporting of the data (when a compliant outcome scoring system was used; N = 32), unavailability of full text (N = 27), paper could not be translated (N = 11) or because less than five patients were included (N = 42). Additional studies were excluded (N = 622) because of other reasons, mainly including the study did not involve PWS patients, no or unclear intervention and no assessment of treatment efficacy. A total of 65 full‐text studies (i.e. 24.3% of eligible studies) comprising 6207 patients and 73 treatment arms met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The data encompass prospective and retrospective studies, different types of lasers and laser settings, various patient populations (with differences in age, skin phototypes, etc.), various lesions (hypertrophic or flat, pink or purple, etc.), untreated patients and previously treated or even therapy‐resistant patients, and single and multiple treatment sessions (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| All studies (N = 65 publications) | |

|---|---|

| Country where study was performed, N (%) | China 15 (23.1), USA 10 (15.4), UK 9 (13.8), Japan 3 (4.6), Germany 7 (10.8), Korea 4 (6.2), Turkey 3 (4.6), Switzerland 2 (3.1), Iraq 2 (3.1), Denmark 2 (3.1), India 2 (3.1), Singapore 1 (1.5), Slovenia 1 (1.5), Poland 1 (1.5), Spain 1 (1.5), Italy 1 (1.5), Taiwan 1 (1.5) |

| Treatment centres, N | 59 |

| Therapy, N (% of treatment arms, N = 73 a) | |

| PDL | |

| 577 nm | 1 (1.4) |

| 585 nm | 17 (23.3) |

| 595 nm | 16 (21.9) |

| 577 nm or 585 nm | 1 (1.4) |

| 585 nm or 595 nm | 1 (1.4) |

| 585 nm and/or 595 nm | 1 (1.4) |

| Nd:YAG | |

| 532 nm | 11 (15.1) |

| 1064 nm | 5 (6.9) |

| PDL (585 nm) and/or Nd:YAG (532 nm) | 1 (1.4) |

| Alexandrite (755 nm) | 2 (2.7) |

| IPL (various wavelengths) | 8 (11.0) |

| CVL (511 + 578 nm) | 1 (1.4) |

| PDT | |

| HMME (510.6 nm + 578.2 nm) | 2 (2.7) |

| Combinatorial modalities | |

| Nd:YAG (1064 nm + 532 nm) | 1 (1.4) |

| DL (800 nm) + PDL (585 nm) | 1 (1.4) |

| PDL (595 nm) + Nd:YAG (1064 nm) | 3 (4.1) |

| ICG + DL (800 nm) | 1 (1.4) |

| Age category, N (%) | |

| <18 years only | 6 (9.2) |

| >18 years only | 13 (20.0) |

| All ages | 46 (70.8) |

| Previous treatment, N (%) | |

| Yes | 19 (29.2) |

| No | 27 (41.5) |

| Applied in <10% of patients | 4 (6.2) |

| NL | 15 (23.1) |

| PWS localization, N (%) | |

| Face and neck only | 10 (15.4) |

| Face only | 13 (20.0) |

| Extremities | 2 (3.1) |

| Various | 37 (56.9) |

| NL | 3 (4.6) |

| PWS types, N (%) | |

| Flat lesions only | 25 (38.5) |

| Therapy‐resistant only | 5 (7.7) |

| Hypertrophic only | 2 (3.1) |

| Hypertrophic or therapy‐resistant | 2 (3.1) |

| Various | 11 (16.9) |

| NL | 20 (30.7) |

| Cooling, N (% of laser applications, N = 80 a) | |

| Contact cooling | 15 (18.8) |

| Cryogen spray cooling | 30 (37.5) |

| Air cooling | 7 (8.8) |

| No cooling | 28 (35.0) |

| Study design, N (%) | |

| Prospective | 46 (70.7) |

| Retrospective | 19 (29.2) |

| Number of treatments, N (%) | |

| Multiple treatment sessions | 53 (81.5) |

| Single treatment | 11 (16.9) |

| NL | 1 (1.5) |

Discrepancy between the number of treatment arms (73), the total number of studies (65) and the number of laser applications (80) stems from the fact that some studies encompassed multiple therapies and dual light source applications.

CVL, copper vapour laser; DL, diode laser; HMME, hematoporphyrin monomethyl ether; ICG, indocyanine green; IPL, intense pulsed light; N, sample size; Nd:YAG, neodymium‐doped yttrium aluminium garnet; NL, not listed; PDL, pulsed dye laser; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PWS, port wine stain.

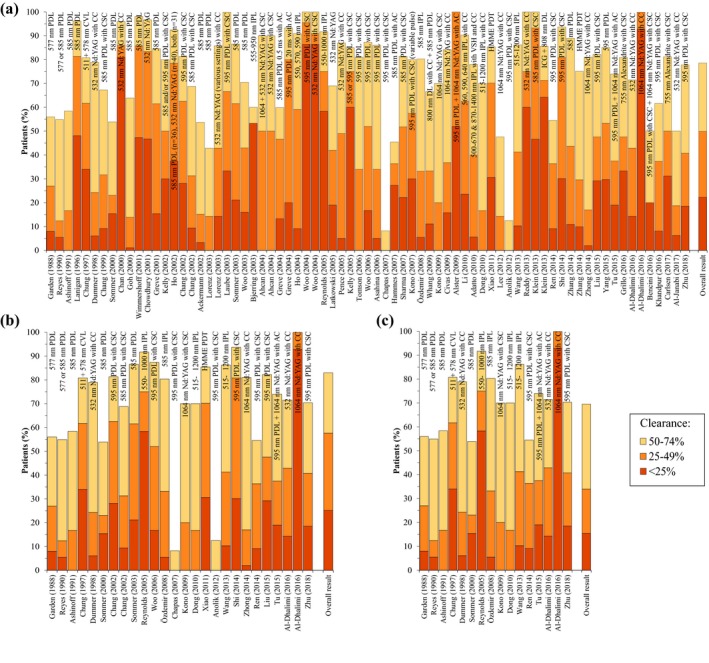

In the first analysis, the data were unclustered to reflect the clinical reality in its broadest sense (Fig. 1a).6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 In terms of interventions, a rapid switch from the 577‐nm PDL to longer‐wavelength (585 and 595 nm) PDLs is noted. Concurrently, the copper vapour laser was abandoned. Around the year 2000, a diversification in light sources occurred as the 532‐nm Nd:YAG/potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser and intense pulsed light (IPL) were introduced in the experimental clinical setting. Around the same time, cryogen spray cooling technology was implemented. In the last decade, almost all laser therapies have been performed in conjunction with some form of epidermal cooling. During the last 15 years, various combinatorial treatments, such as the concomitant use of the PDL and Nd:YAG laser, have been studied. Also, hematoporphyrin monomethyl ether and other photodrugs have been explored as photosensitizers in PDT‐based PWS treatment.

Figure 1.

Clearance rates reported in port wine stain studies published since 1986. Panel (a) shows all studies. Panel (b) includes only studies in which previously untreated patients were given multiple treatments. In panel (c) retrospective studies were excluded from the panel (b) data set. The clearance rates are stratified in quartiles according to the legend (bottom) and presented in chronological order. Every bar represents one study or one treatment arm. The respective year of publication and first author are referenced below the bar. The treatment specifics are listed in or above the bar. The proportion of patients is plotted on the y‐axis, with 100% representing all the patients in the study or treatment arm. Note that the white area above each column represents the fraction of patients in the 75–100% clearance category. The column on the far right comprises the overall result per outcome category based on the overall study population. AC, air cooling; CC, contact cooling; CSC, cryogen spray cooling; CVL, copper vapour laser; DL, diode laser; HMME, hematoporphyrin monomethyl ether; IPL, intense pulsed light; Nd:YAG, neodymium‐doped yttrium aluminium garnet; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PDL, pulsed dye laser; VSH, vascular‐specific handpiece.

With respect to clearance rates, the most striking result is that the data do not reveal a general improvement in treatment outcomes upon visual inspection (hence no further trend analysis with statistical methods was performed). This is mainly evidenced by the visually narrowing white area in time (Fig. 1a), indicating that the fraction of patients with 75–100% clearance is not getting larger towards present day while new technologies enter the clinical setting and mature. One would expect a visually broadening impression of the white region from left to right if the introduction of novel technologies had actually translated to improved treatment efficacy, having resulted in a gradually larger fraction of patients exhibiting the highest level of clearance. A concurrent tapered pattern over time would also be expected in the other (coloured) categories, but such an effect is absent. The two studies from Anolik et al. and Chapas et al. stand out because of their superior results.33, 48 This is likely a result of highly specific patient selection inasmuch as these studies focused exclusively on facial PWS in children ≤16 weeks or ≤6 months of age, which is an age category and lesion location typically associated with good treatment efficacy.57, 71

Innovations in PWS treatment modalities also get lost in translation in more case‐matched analysis

To make a more valid comparison of treatment results in time, trials were analysed in which previously untreated patients received multiple treatments (Fig. 1b) and where retrospective studies were excluded from the trials where previously untreated patients received multiple treatments (Fig. 1c). The overall scores included in all panels (which weigh data based on cohort size) show that the best results were achieved in the prospective studies with previously untreated patients, with 30.5% of all included patients having 75–100% clearance (vs. 21.4% and 17.0% for Fig. 1 panel a and b, respectively). Nevertheless, no improvement in treatment efficacy over time is noted in either analysis when the data are interpreted in chronological context as explained above (section The global clinical reality in the face of 30 years of technological innovations).

As in the clustered data set (Fig. 1a), the proportion of patients in the more case‐matched studies that achieved the desired outcome (75–100% clearance) and suboptimal outcomes (25–49% and 50–74% clearance) has not notably changed over the last three decades (Fig. 1b,c). In fact, only a handful of studies report a greater proportion of 75–100% clearance than the studies performed in 1988–1991. The proportion of patients with the worst outcome (0–24% clearance) is 0% in a few studies, but remains substantial in most (Fig. 1a–c). These observations are further echoed by the fact that most of the outcome category bars in individual studies/treatment arms are larger than the respective bar of the overall result per outcome category of all studies (most right bar in Fig. 1a–c), reflecting a worse outcome than the mean.

Trend analysis affirms the absence of treatment efficacy improvement over time

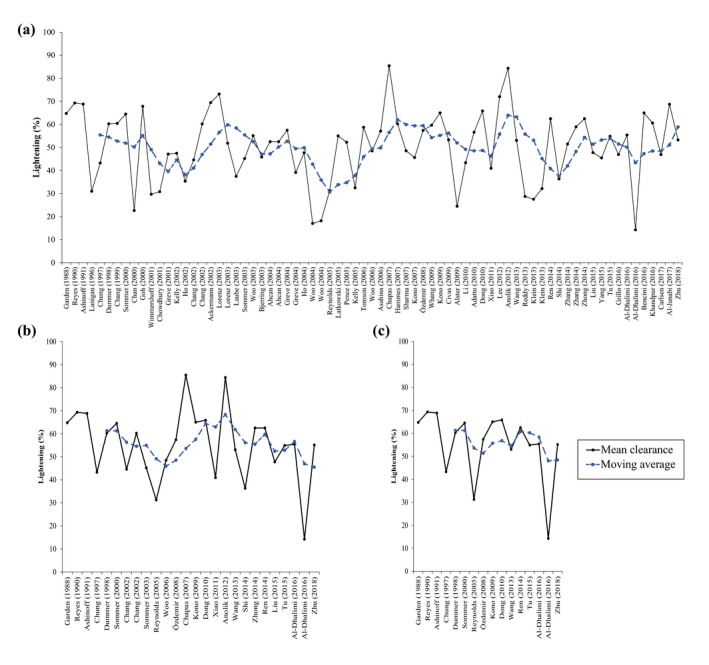

To put the data in better perspective, the outcomes of all included studies were converted into an average clearance score per study () and plotted as a function of time. Additionally, a five‐study/treatment arm simple moving average () was calculated for each of the subsets from Fig. 1 (average time span: 2.5, 5.5 and 9.3 years for Fig. 2a–c, respectively) to ameliorate the effect of incidental outliers on the mean treatment outcomes. What becomes evident from Fig. 2a–c is that, although the moving averages resemble a sinusoidal waveform, neither trace exhibits a long‐term upward trend, yielding credence to the previous conclusions.

Figure 2.

The mean clearance score per study or treatment arm (; black line) and the five‐study/treatment arm simple moving average for clearance (; blue dotted line) are plotted in chronological order. The panels (a–c) correspond to the panels and data subsets in Fig. 1.

It could be argued that some studies may have achieved relatively poor outcomes as a result of study design, for example, by inclusion of patients with difficult‐to‐treat dark skin or hypertrophic PWS. When studies with the highest average clearance scores only are considered, however, nothing changes in the trend and therefore this argument does not hold.

In summary, only few studies in the past 20+ years have been able to match or exceed the results obtained with the 577‐ and 585‐nm PDL in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. None of the technological innovations seem to have materialized clinically in a beneficial manner for patients in terms of PWS clearance.

Discussion

The selective destruction of superficial hyperdilated dermal vasculature has been subject to much research since the inception of SP by Anderson and Parrish in 1983.72 A large portion of the research that drove the technological and conceptual innovations to optimize SP was based on fundamental principles related to the optical and thermal responses of laser‐irradiated dermal tissue. Mathematical modelling of these responses brought about a shift to longer wavelengths, longer pulse durations and larger spot sizes, which ultimately had to be accommodated by epidermal cooling to counter thermal skin damage. Unfortunately, the (patho)biology in the skin heeded little attention to the vast number of photophysical and thermodynamic elaborations, leaving the field with little or no improvement in PWS clearance in over three decades and the patients with unresolved medical issues. This is especially disappointing considering the long‐term risk of PWS redarkening and tissue hypertrophy.73 Moreover, our analysis unveiled that SP and current treatments modalities are intrinsically limited in their capacity to clear all PWS,74 leaving a substantial proportion of patients with no alternative treatment options. All the while, patient demand for improved therapies has not abated, which is hardly surprising considering the reduced quality of life that PWS patients experience.3, 75, 76

It is therefore vital that new therapeutic strategies are adopted using different approaches, where emphasis is placed on the underlying (patho)biology rather than photophysics per se. In light of this, the recent discovery that PWS vasculature is characterized by differentiation‐impaired endothelial cells that co‐express the arterial and venous markers ephrin receptor B1 and ephrin B2 (probably as a result of sporadic somatic mutations in the GNAQ gene)77, 78 may lead to pharmacological modulators that stimulate the normal differentiation of PWS endothelial progenitor cells.79 In the future, these could potentially be used to ensure normal development of dermal vascular plexi post‐treatment and improve treatment outcomes. In addition, site‐specific pharmaco‐laser therapy may constitute a promising treatment modality designed to target therapy‐resistant blood vessels by augmenting laser‐induced thrombosis and complete lumenal occlusion of PWS vasculature. Laser‐induced thrombosis is a biological response to SP in incompletely photocoagulated blood vessels,80 while the complete occlusion of target vessels is considered a clinical end point for complete PWS clearance.81

Lastly, there are some limitations to the study that warrant contextualization of the conclusions. First, the data are incomplete as studies that used other outcome scoring systems were excluded (because of this, for example, no studies with pharmacological interventions could be included). Second, trial results do not directly represent non‐trial clinical results insofar as better outcomes may be achieved in individual patients with the use of varying lasers and laser settings. The physicians’ experience‐based improvisations are not accounted for in the rigorous design of clinical trials. Third, the study outcomes do not take into consideration other important therapy aspects, such as patient discomfort or adverse effects.

In conclusion, the efficacy of PWS therapy in clinical trials has not improved in the past decades and remains limited, despite technical innovations. With an unwavering patient demand for better solutions, the need for development and implementation of novel therapeutic strategies is as valid today as it was 30 years ago.

Conflict of interest

MH owns intellectual property rights to site‐specific pharmaco‐laser therapy (SSPLT). There are no other financial arrangements or potential conflicts of interest related to this article.

Funding sources

MH was financially supported by a preseed grant from the Academic Medical Center SKE Fund (Technostarter # 20090812) and a valorization grant from Stichting Technologische Wetenschap (STW, project # 12064).

References

- 1. Chen JK, Ghasri P, Aguilar G et al An overview of clinical and experimental treatment modalities for port wine stains. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 289–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aguilar G, Choi B, Broekgaarden M et al An overview of three promising mechanical, optical, and biochemical engineering approaches to improve selective photothermolysis of refractory port wine stains. Ann Biomed Eng 2012; 40: 486–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Raath MI, Bambach CA, Dijksman LM, Wolkerstorfer A, Heger M. Prospective analysis of the port‐wine stain patient population in the Netherlands in light of novel treatment modalities. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2018; 20: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Raath MI, Chohan S, van der Horst CM, Wolkerstorfer A, Limpens J, Heger M. A systematic review of clinical outcome scoring systems used in prospective studies of port wine stains. [Manuscript submitted]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Murphy JJ, editor. Moving averages In: Technical Analysis of the Financial Markets: A Comprehensive Guide to Trading Methods and Applications, 2nd ed New York Institute of Finance, Paramus, NJ, 1999: 195–223. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garden JM, Polla LL, Tan OT. The treatment of port‐wine stains by the pulsed dye laser. Analysis of pulse duration and long‐term therapy. Arch Dermatol 1988; 124: 889–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reyes BA, Geronemus R. Treatment of port‐wine stains during childhood with the flashlamp‐pumped pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 23(6 Pt 1): 1142–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chowdhury MMU, Harris S, Lanigan SW. Potassium titanyl phosphate laser treatment of resistant port‐wine stains. Br J Dermatol 2001; 144: 814–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Greve B, Hammes S, Raulin C. The effect of cold air cooling on 585 nm pulsed dye laser treatment of port‐wine stains. Dermatol Surg 2001; 27: 633–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wimmershoff MB, Wenig M, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Die behandlung von feuermalen mit dem blitzlampengepumpten gepulsten farbstofflaser. Ergebnisse aus 5 jahren klinischer Erfahrung. Hautarzt 2001; 52: 1011–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kelly KM, Nanda VS, Nelson JS. Treatment of port‐wine stain birthmarks using the 1.5‐msec pulsed dye laser at high fluences in conjunction with cryogen spray cooling. Dermatol Surg 2002; 28: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ho WS, Chan HH, Ying SY, Chan PC. Laser treatment of congenital facial port‐wine stains: long‐term efficacy and complication in Chinese patients. Lasers Surg Med 2002; 30: 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang C‐J, Kelly KM, Van Gemert MJC, Nelson JS. Comparing the effectiveness of 585‐nm vs 595‐nm wavelength pulsed dye laser treatment of port wine stains in conjunction with cryogen spray cooling. Lasers Surg Med 2002; 31: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ackermann G, Hartmann M, Scherer K et al Correlations between light penetration into skin and the therapeutic outcome following laser therapy of port‐wine stains. Lasers Med Sci 2002; 17: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lorenz S, Scherer K, Wimmershoff MB, Landthaler M, Hohenleutner U. Variable pulse frequency‐doubled Nd:YAG laser versus flashlamp‐pumped pulsed dye laser in the treatment of port wine stains. Acta Derm Venereol 2003; 83: 210–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laube S, Taibjee S, Lanigan SW. Treatment of resistant port wine stains with the v beam pulsed dye laser. Lasers Surg Med 2003; 33: 282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bjerring P, Christiansen K, Troilius A. Intense pulsed light source for treatment of dye laser resistant port‐wine stains. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2003; 5: 7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ashinoff R, Geronemus RG. Flashlamp‐pumped pulsed dye laser for port‐wine stains in infancy: earlier versus later treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24: 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Woo WK, Handley JM. Does fluence matter in the laser treatment of port‐wine stains? Clin Exp Dermatol 2003; 28: 556–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sommer S, Seukeran DC, Sheehan‐Dare RA. Efficacy of pulsed dye laser treatment of port wine stain malformations of the lower limb. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149: 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahcan U, Zorman P, Recek D, Ralca S, Majaron B. Port wine stain treatment with a dual‐wavelength Nd:Yag laser and cryogen spray cooling: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med 2004; 34: 164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greve B, Raulin C. Prospective study of port wine stain treatment with dye laser: comparison of two wavelengths (585 nm vs. 595 nm) and two pulse durations (0.5 milliseconds vs. 20 milliseconds). Lasers Surg Med 2004; 34: 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ho WS, Ying SY, Chan PC, Chan HH. Treatment of port wine stains with intense pulsed light: a prospective study. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30: 887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woo WK, Jasim ZF, Handley JM. Evaluating the efficacy of treatment of resistant port‐wine stains with variable‐pulse 595‐nm pulsed dye and 532‐nm Nd:YAG lasers. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reynolds N, Exley J, Hills S, Falder S, Duff C, Kenealy J. The role of the Lumina intense pulsed light system in the treatment of port wine stains–a case controlled study. Br J Plast Surg 2005; 58: 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Latkowski IT, Wysocki MS, Siewiera IP. [Own clinical experience in treatment of port‐wine stain with KTP 532 nm laser]. Wiad Lek 2005; 58: 391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pençe B, Aybey B, Ergenekon G, Pence B, Aybey B, Ergenekon G. Outcomes of 532 nm frequency‐doubled Nd:YAG laser use in the treatment of port‐wine stains. Dermatol Surg 2005; 31: 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kelly KM, Choi B, McFarlane S et al Description and analysis of treatments for port‐wine stain birthmarks. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2005; 7: 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lanigan SW. Port wine stains on the lower limb: response to pulsed dye laser therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21: 88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tomson N, Lim SP, Abdullah A, Lanigan SW. The treatment of port‐wine stains with the pulsed‐dye laser at 2‐week and 6‐week intervals: a comparative study. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154: 676–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Woo S‐H, Ahn H‐H, Kim S‐N, Kye Y‐C. Treatment of vascular skin lesions with the variable pulse 595 nm pulsed dye laser. Dermatol Surg 2006; 32: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Asahina A, Watanabe T, Kishi A et al Evaluation of the treatment of port‐wine stains with the 595‐nm long pulsed dye laser: a large prospective study in adult Japanese patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54: 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chapas AM, Eickhorst K, Geronemus RG. Efficacy of early treatment of facial port wine stains in newborns: a review of 49 cases. Lasers Surg Med 2007; 39: 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hammes S, Roos S, Raulin C, Ockenfels HM, Greve B. Does dye laser treatment with higher fluences in combination with cold air cooling improve the results of port‐wine stains? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 1229–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Efficacy of pulsed dye laser in facial port‐wine stains in Indian patients. Dermatol Surg 2007; 33: 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kono T, Sakurai H, Takeuchi M et al Treatment of resistant port‐wine stains with a variable‐pulse pulsed dye laser. Dermatol Surg 2007; 33: 951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Özdemir M, Engin B, Mevlitoglu I. Treatment of facial port‐wine stains with intense pulsed light: a prospective study. J Cosmet Dermatol 2008; 7: 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whang KK, Byun JY, Kim SH. A dual‐wavelength approach with 585‐nm pulsed‐dye laser and 800‐nm diode laser for treatment‐resistant port‐wine stains. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009; 34: 436–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kono T, Frederick GW, Chan HH, Sakurai H, Yamaki T. Long‐pulsed neodymium:yttrium‐aluminum‐garnet laser treatment for hypertrophic port‐wine stains on the lips. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2009; 11: 11–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chung JH, Koh WS, Lee DY, Lee YS, Eun HC, Youn J Il. Copper vapour laser treatment of port‐wine stains in brown skin. Australas J Dermatol 1997; 38: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Civas E, Koc E, Aksoy B, Aksoy HM. Clinical experience in the treatment of different vascular lesions using a neodymium‐doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. Dermatol Surg 2009; 35: 1933–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alster TS, Tanzi EL. Combined 595‐nm and 1,064‐nm laser irradiation of recalcitrant and hypertrophic port‐wine stains in children and adults. Dermatol Surg 2009; 35: 914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li G, Lin T, Wu Q, Zhou Z, Gold MH. Clinical analysis of port wine stains treated by intense pulsed light. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2010; 12: 2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adatto MA, Luc‐Levy J, Mordon S. Efficacy of a novel intense pulsed light system for the treatment of port wine stains. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2010; 12: 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dong X, Yu Q, Ding J, Lin J. Treatment of facial port‐wine stains with a new intense pulsed light source in Chinese patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2010; 12: 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xiao Q, Li Q, Yuan KH, Cheng B. Photodynamic therapy of port‐wine stains: long‐term efficacy and complication in Chinese patients. J Dermatol 2011; 38: 1146–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee HR, Han TY, Kim Y‐G, Lee JH. Clinical experience in the treatment of port‐wine stains with blebs. Ann Dermatol 2012; 24: 306–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anolik R, Newlove T, Weiss ET et al Investigation into optimal treatment intervals of facial port‐wine stains using the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang B, Wu Y, Zhu X et al Treatment of neck port‐wine stain with intense pulsed light in Chinese population. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2013; 15: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reddy KK, Brauer JA, Idriss MH et al Treatment of port‐wine stains with a short pulse width 532‐nm Nd:YAG laser. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12: 66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dummer R, Graf P, Greif C, Burg G. Treatment of vascular lesions using the VersaPulse variable pulse width frequency doubled neodymium:YAG laser. Dermatology 1998; 197: 158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klein A, Baumler W, Buschmann M, Landthaler M, Babilas P. A randomized controlled trial to optimize indocyanine green‐augmented diode laser therapy of capillary malformations. Lasers Surg Med 2013; 45: 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ren J, Qian H, Xiang L et al The assessment of pulsed dye laser treatment of port‐wine stains with reflectance confocal microscopy. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2014; 16: 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shi W, Wang J, Lin Y et al Treatment of port wine stains with pulsed dye laser: a retrospective study of 848 cases in Shandong Province, People's Republic of China. Drug Des Devel Ther 2014; 8: 2531–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang B, Zhang T‐HH, Huang Z, Li Q, Yuan K‐HH, Hu Z‐QQ. Comparison of pulsed dye laser (PDL) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for treatment of facial port‐wine stain (PWS) birthmarks in pediatric patients. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2014; 11: 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhong SX, Liu YY, Yao L et al Clinical analysis of port‐wine stain in 130 Chinese patients treated by long‐pulsed 1064‐nm Nd: YAG laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2014; 16: 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu X, Fan Y, Huang J et al Can we predict the outcome of 595‐nm wavelength pulsed dye laser therapy on capillary vascular malformations from the first beginning: a pilot study of efficacy co‐related factors in 686 Chinese patients. Lasers Med Sci 2015; 30: 1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang B, Li L, Zhang L, Sun Y, Ma L. Clinical characteristics and treatment options of infantile vascular anomalies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tu H, Li Y, Xie H et al A split‐face study of dual‐wavelength laser on neck and facial port‐wine stains in Chinese patients. J Drugs Dermatol 2015; 14: 1336–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Grillo E, González‐Muñoz P, Boixeda P, Cuevas A, Vañó S, Jaén P. Alexandrite laser for the treatment of resistant and hypertrophic port wine stains: a clinical, histological and histochemical Study. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2016; 107: 591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Al‐Dhalimi MA, Al‐Janabi MH. Split lesion randomized comparative study between long pulsed Nd:YAG laser 532 and 1,064 nm in treatment of facial port‐wine stain. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48: 852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chang CJ, Nelson JS. Cryogen spray cooling and higher fluence pulsed dye laser treatment improve port‐wine stain clearance while minimizing epidermal damage. Dermatol Surg 1999; 25: 767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bencini PL, Tourlaki A, Tretti Clementoni M, Naldi L, Galimberti M. Double phase treatment with flashlamp‐pumped pulsed‐dye laser and long pulsed Nd:YAG laser for resistant port wine stains in adults. Preliminary reports. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2016; 151: 281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Khandpur S, Sharma VK. Assessment of efficacy of the 595‐nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of facial port‐wine stains in Indian patients. Dermatol Surg 2016; 42: 717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Carlsen BC, Wenande E, Erlendsson AM, Faurschou A, Dierickx C, Haedersdal M. A randomized side‐by‐side study comparing alexandrite laser at different pulse durations for port wine stains. Lasers Surg Med 2017; 49: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Al‐janabi MH, Ismaeel Ali NT, Mohamed Al‐Sabti KD, Al‐Dhalimi MA, Abdul Wahid SN. A new imaging technique for assessment of the effectiveness of long pulse Nd:YAG 532 nm laser in treatment of facial port wine stain. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2017; 19: 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhu J, Yu W, Wang T et al Less is more: similar efficacy in three sessions and seven sessions of pulsed dye laser treatment in infantile port‐wine stain patients. Lasers Med Sci 2018; 33: 1707–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sommer S, Sheehan‐Dare RA. Pulsed dye laser treatment of port‐wine stains in pigmented skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42: 667–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chan HH, Chan E, Kono T, Ying SY, Ho WS. The use of variable pulse width frequency doubled Nd:YAG 532 nm laser in the treatment of port‐wine stain in Chinese patients. Dermatol Surg 2000; 26: 657–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Goh CL. Flashlamp‐pumped pulsed dye laser (585 nm) for the treatment of portwine stains–a study of treatment outcome in 94 Asian patients in Singapore. Singapore Med J 2000; 41: 24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Morelli JG, Weston WL, Huff JC, Yohn JJ. Initial lesion size as a predictive factor in determining the response of port‐wine stains in children treated with the pulsed dye laser. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995; 149: 1142–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis : precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science 1983; 220: 524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Huikeshoven M, Koster PH, de Borgie CA, Beek JF, van Gemert MJ, van der Horst CM. Redarkening of port‐wine stains 10 years after pulsed‐dye‐laser treatment. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Heger M, Beek J, Moldovan N, van der Horst C, van Gemert M. Towards optimization of selective photothermolysis: prothrombotic pharmaceutical agents as potential adjuvants in laser treatment of port wine stains. A theoretical study. Thromb Haemost 2005; 93: 242–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hagen SL, Grey KR, Korta DZ, Kelly KM. Quality of life in adults with facial port‐wine stains. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schiffner R, Brunnberg S, Hohenleutner U, Stolz W, Landthaler M. Willingness to pay and time trade‐off: useful utility indicators for the assessment of quality of life and patient satisfaction in patients with port wine stains. Br J Dermatol 2002; 146: 440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tan W, Nadora DM, Gao L, Wang G, Mihm MC, Nelson JS. The somatic GNAQ mutation (R183Q) is primarily located within the blood vessels of port wine stains. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 380–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ et al Sturge‐Weber syndrome and port‐wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1971–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tan W, Wang J, Zhou F et al Coexistence of Eph receptor B1 and ephrin B2 in port‐wine stain endothelial progenitor cells contributes to clinicopathological vasculature dilatation. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 1601–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Heger M, Salles II, Bezemer R et al Laser‐induced primary and secondary hemostasis dynamics and mechanisms in relation to selective photothermolysis of port wine stains. J Dermatol Sci 2011; 63: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hohenleutner U, Hilbert M, Wlotzke U, Landthaler M. Epidermal damage and limited coagulation depth with the flashlamp‐pumped pulsed dye laser: a histochemical study. J Invest Dermatol 1995; 104: 798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]