Abstract

Skeletal muscle consists of bundles of myofibers containing millions of myofibrils, each of which is formed of longitudinally aligned sarcomere structures. Sarcomeres are the minimum contractile unit, which mainly consists of four components: Z‐bands, thin filaments, thick filaments, and connectin/titin. The size and shape of the sarcomere component is strictly controlled. Surprisingly, skeletal muscle cells not only synthesize a series of myofibrillar proteins but also regulate the assembly of those proteins into the sarcomere structures. However, authentic sarcomere structures cannot be reconstituted by combining purified myofibrillar proteins in vitro, therefore there must be an elaborate mechanism ensuring the correct formation of myofibril structure in skeletal muscle cells. This review discusses the role of myosin, a main component of the thick filament, in thick filament formation and the dynamics of myosin in skeletal muscle cells. Changes in the number of myofibrils in myofibers can cause muscle hypertrophy or atrophy. Therefore, it is important to understand the fundamental mechanisms by which myofibers control myofibril formation at the molecular level to develop approaches that effectively enhance muscle growth in animals.

Keywords: myofibril, myosin, sarcomere, skeletal muscle, thick filament

1. INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle is the largest tissue in the animal body, accounting for 40%–50% of body weight and playing an essential role in motion. One of the most distinctive features of skeletal muscle is its plasticity, as it can increase or decrease its mass (hypertrophy or atrophy, respectively) in response to environmental factors such as growth, aging, and exercise. Muscle remodeling is caused by increasing or decreasing the cross‐sectional area of muscle fibers (myofibers), as an increase or decrease in the number of myofibrils in myofibers directly leads to muscle hypertrophy or atrophy, respectively. The extracellular growth factors that induce muscle hypertrophy or atrophy, such as myostatin (growth differentiation factor‐8, GDF‐8; McPherron, Lawler, & Lee, 1997) and insulin‐like growth factor‐I (Barton‐Davis, Shoturma, Musaro, Rosenthal, & Sweeney, 1998) have received considerable attention. However, little attention has been paid to the mechanisms underlying the assembly and structural maintenance of myofibrils. In this review, to better understand these fundamental issues regarding hypertrophy and atrophy in skeletal muscle, we focus on the thick filament and its main component, myosin. First, we describe the structure of myofibrils in the skeletal muscle, then consider myosin and thick filament structure, and finally discuss myosin replacement and maintenance of thick filament structure in myofibrils.

1.1. Structure and components of the myofibril in skeletal muscles

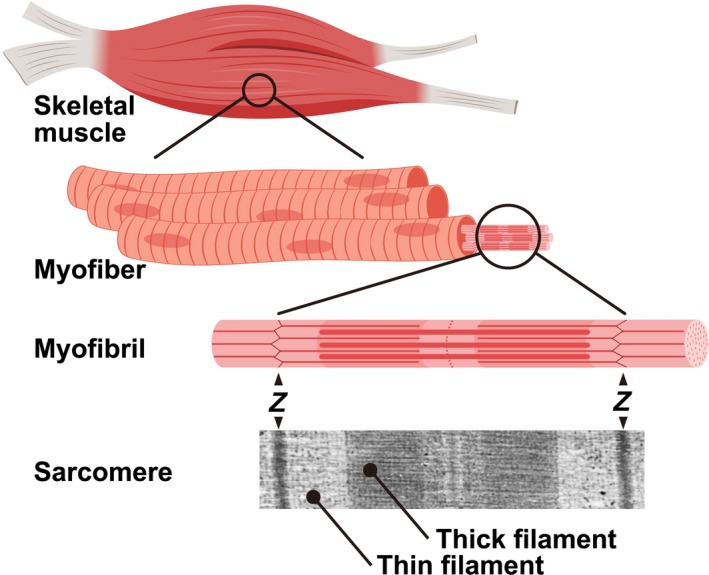

Skeletal muscle tissue is composed of bundles of myofibers packed by intramuscular connective tissues consisting of extracellular matrix molecules. Each myofiber is a single, long, multinucleated cell approximately 0.1 mm in diameter, which varies in length, and is filled with numerous myofibrils consisting of tandemly aligned sarcomeres. The sarcomere is the smallest basic contractile unit and is the most regular macromolecular protein complex (Figure 1). Thus, skeletal muscle fibers are entirely dedicated to generating force.

Figure 1.

Structure of myofibrils in the myofiber. Skeletal muscle tissue consists of bundles of myofibers. Each myofiber contains millions of myofibrils that are comprised of longitudinally aligned sarcomeres. The sarcomere is the minimum contractile unit, which consists of Z‐bands, thin filaments, thick filaments and connectin/titin. Z‐bands are indicated by “Z”. A transmission electron micrograph of the sarcomere structure is shown at the bottom of panel. Connectin/titin is omitted in a model of "Myofibril". The figure was created using BioRender

The sarcomere has a highly ordered semi‐crystal structure consisting of four main components: Z‐bands, thin filaments, thick filaments, and connectin/titin. The size of each sarcomere component is highly regulated, and each component is formed of a substantial number of myofibrillar proteins and their associated proteins (Henderson, Gomez, Novak, Mi‐Mi, & Gregorio, 2017; Sweeney & Hammers, 2018). The Z‐band is a complex protein network which coordinates the contraction generated by individual sarcomeres. Its major components are sarcomeric‐α‐actinin, (s‐α‐actinin), α‐actin, T‐cap, C‐terminus of nebulin, and N‐terminus of connectin/titin (Gregorio, Granzier, Sorimachi, & Labeit, 1999). The thickness of the Z‐band is 30–120 nm depending on the type of muscle fiber (Engel & Franzini‐Armstrong, 2004). The thin filament consists of α‐actin, tropomyosin, the troponin complex, tropomodulin, and nebulin. Although the length of the thin filament is known to vary depending on developmental stage (Ohtsuki, 1979), Gokhin et al. recently revealed that the thin filament is longer in slow type myofibers than in fast type myofibers (Gokhin et al., 2012). The bipolar thick filament is formed of approximately 300 myosin molecules and their associated proteins (Craig & Offer, 1976; Luther, Munro, & Squire, 1981). It has a strictly uniform dimension of 1.6 µm in length and 15 nm in diameter, which is independent of the type of muscle fiber (Huxley, 1963). The thick filament is located at the center of the sarcomere as the giant elastic protein connectin/titin spans half sarcomere along the thick filaments, linking the Z‐band and the M‐lines (Labeit & Kolmerer, 1995; Maruyama, 1976; Wang, McClure, & Tu, 1979). Connectin/titin provides the sarcomere not only with passive tension (Horowits, Kempner, Bisher, & Podolsky, 1986; Trombitas et al., 2000) but also acts as a scaffold for associated proteins, which are implicated in connectin/titin‐based signaling pathways (Miller et al., 2003; Ojima et al., 2010).

1.2. Myosin: One of the main myofibrillar proteins in skeletal muscles

Myosin is the most abundant myofibrillar protein, accounting for more than 40% of the myofibrillar proteins in skeletal muscle (Yates & Greaser, 1983). Myosins are a large superfamily of motor proteins which play key roles in the fundamental cellular functions of nonmuscle and muscle cells, such as locomotion, cytokinesis, and contraction (Engel & Franzini‐Armstrong, 2004; Sellers, 2000). The sarcomeric myosins specifically expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells to generate contractile force are categorized as either conventional myosins or class II myosins.

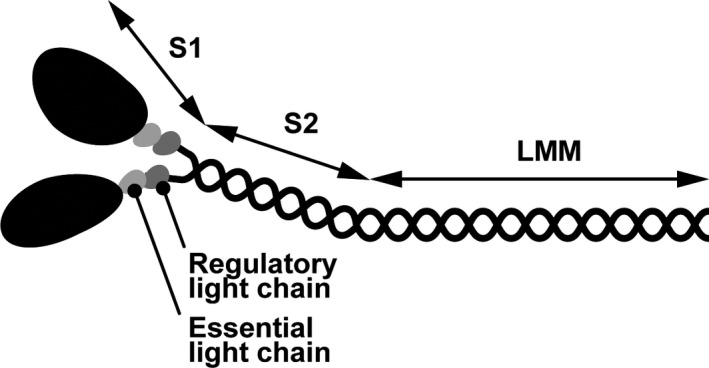

A single myosin molecule consists of two myosin heavy chains (MYHs), which interact with two pairs of myosin regulatory light chains and myosin essential light chains to form a hexamer (Weeds & Lowey, 1971). Sarcomeric myosin is generally divided into the head domain and the rod domain (Figure 2). The head domain [subfragment‐1 (S1)] is located at the N‐terminus of myosin and is the motor domain that generates force by ATP hydrolysis when myosin interacts with actin‐containing thin filaments. Thus, S1 determines the biochemical and physiological functions of myosin, such as ATPase activity and actin‐filament velocity (Resnicow, Deacon, Warrick, Spudich, & Leinwand, 2010). The rod domain is proteolytically cleaved into subfragment‐2 (S2) and light meromyosin (LMM). S2 has an α‐coiled‐coil structure, which links S1 and LMM. The remaining C‐terminal rod domain, LMM, mediates the dimerization of MYH to form myosin. A hinge region of MYH, which is a less stable coiled‐coil structure i.e., short random coil structure, links the S2 and LMM domains (Miller et al., 2009; Suggs et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Schematic model of sarcomeric myosin. Sarcomeric myosin is formed by a pair of myosin heavy chains, essential light chains, and regulatory light chains. The N‐terminus of myosin is S1, referred to as the head, which contains nucleotide and actin binding sites. The rest of myosin is the rod, which is further divided into two parts, S2 and LMM, which form an α‐helical coiled‐coil structure

1.3. Assembly of myosin into thick filaments

Sarcomeric myosin has the remarkable ability to form highly organized bipolar thick filaments in myofibrils. Extensive biochemical studies have demonstrated that thick filament formation is mediated by the distribution of charge along LMM (Atkinson & Stewart, 1991; Sohn et al., 1997). Myosin forms filaments in an antiparallel fashion at the center of the thick filament, while myosin forms filaments in a parallel way in the rest of the thick filament. Consequently, a bipolar thick filament is formed, leaving a central bare zone in the middle.

Which myosin domain is critical for forming the thick filament in skeletal muscle cells? To answer this, we evaluated whether the thick filament is formed by exogenously expressed‐MYH deletion variants in cultured skeletal muscle cells. S1 is dispensable for thick filament formation (Ojima, Oe, et al., 2015b), consistent with the findings of other studies which showed that the thick filament is formed without S1 in Drosophila melanogaster and cultured muscle cells (Cripps, Suggs, & Bernstein, 1999; Thompson, Buvoli, Buvoli, & Leinwand, 2012). S2‐LMM is perfectly incorporated into the entire thick filament, while the expression of S2 alone does not form any structure with S2 diffusing into the cytoplasm. Furthermore, LMM is incorporated into the restricted region of the thick filament, in the vicinity of the central bare zone. These results demonstrate that the LMM domain is not sufficient for thick filament formation in cultured muscle cells although it is essential for forming myosin filaments or paracrystals in vitro (Sohn et al., 1997). Interestingly, S2‐LMM with N‐terminal or C‐terminal deletions are assembled into the M‐line neighboring region but not into the entire thick filament. These results suggest that the S2 N‐terminus region and the LMM C‐terminus region (also known as the tail piece) are necessary for incorporation of myosin into the entire thick filament or for thick filament stabilization (Ojima, Oe, et al., 2015b). However, the molecular structure of the thick filament has not yet been completely determined in vertebrates (Irving, 2017).

In nonmuscle COS7 cells, exogenously expressed MYH forms a filamentous structure or aggregates (Moncman, Rindt, Robbins, & Winkelmann, 1993; Ojima, Oe, et al., 2015b; Vikstrom et al., 1997), however, the authentic thick filament does not form. Therefore, it is likely that the myogenic intracellular environment, including unknown myocytosolic factors and/or other myofibrillar proteins such as connectin/titin (Myhre, Hills, Prill, Wohlgemuth, & Pilgrim, 2014; Tonino et al., 2017) is required to generate properly assembled‐thick filaments.

1.4. Replacement of myosin in the thick filament

How often are myosin molecules exchanged in the thick filaments? To address this question, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), which determines the dynamics of fluorescently labeled‐molecules in living cells (Wang et al., 2005). FRAP experiments revealed that green fluorescence protein (GFP)‐tagged MYH molecules are actively and continuously substituted in the thick filaments of cultured myotubes (Ojima, Ichimura, Yasukawa, Wakamatsu, & Nishimura, 2015a). The simultaneous uptake and release of myosin was observed in myofibrils while the half‐life of GFP‐MYH replacing myosin in the thick filament was estimated to be 3–4 hr (Ojima, Ichimura, et al., 2015a). Given that the half‐life of myosin replacement is 3 hr, more than 90% of the myosin molecules in a single thick filament will be replaced within 12 hr. Myosin exchange is maintained in every myofibril of every myotube as long as myotubes are alive since the pioneering works using radioactive isotopes demonstrated that the half‐life of the MYH protein turnover rate, i.e., from synthesis to degradation, is approximately 6 days in vivo and in vitro (McManus & Mueller, 1966; Zak, Martin, Prior, & Rabinowitz, 1977; Rubinstein, Chi, & Holtzer, 1976).

The exchange rate of myofibrillar proteins in other sarcomere components has also been determined by other research groups. The half‐lives of thin filament components (α‐actin and tropomyosin) and Z‐band components (s‐α‐actinin) have been reported as minutes (Littlefield, Almenar‐Queralt, & Fowler, 2001; Wang, Fan, Dube, Sanger, & Sanger, 2014; Wang et al., 2005), whereas the half‐life of the giant molecule connectin/titin is approximately 2 hr (da Silva Lopes, Pietas, Radke, & Gotthardt, 2011). Likewise, the half‐lives of thick filament associated‐proteins, such as myosin binding protein C1 and myomesin, are approximately 2 hr (Ojima, Ichimura, et al., 2015a). The different exchange rates of each myofibrillar protein may, in part, reflect their molecular size, since the rate of protein diffusion is dependent on molecular mass (Papadopoulos, Jurgens, & Gros, 2000). In fact, connectin/titin (~3 MDa) and myosin (~500 KDa) are relatively large molecules compared to α‐actin (~42 KDa), tropomyosin dimers (~66 KDa), and s‐α‐actinin dimers (~200 KDa). Besides molecular size, the structural complexity of the thick filament may account for the slow myosin exchange rate in skeletal muscle cells. In nonmuscle cells, approximately 30 nonmuscle myosin molecules form a bipolar filament. FRAP experiments revealed that the half‐life of nonmuscle myosin exchange is less than one minute, indicating that myosin substitution is more rapid in nonmuscle myosin filaments than in the thick filaments of myofibrils (Hu et al., 2017). The molecular masses of these two distinct myosins (nonmuscle and sarcomeric myosins) are almost identical, however, the number of myosin molecules is 10 times higher in a single thick filament than in a single nonmuscle filament. Furthermore, thick filaments contain myosin‐associated proteins including myosin binding protein C, myomesin, and connectin/titin, which help to pack the filament together. Therefore, the thick filament in striated muscles is larger, more complicated and has a higher‐order structure than the nonmuscle bipolar myosin filaments (Dasbiswas, Hu, Schnorrer, Safran, & Bershadsky, 2018). The intricate structure of thick filaments may reduce the exchange rate of myosin molecules in skeletal muscle cells.

1.5. Sources of myosin for replacement in the thick filament

As myosin molecules are continuously replaced in the thick filament of myofibrils, what are the sources of these replacement myosin molecules? The primary source is de novo synthesized myosin molecules, since newly synthesized myosin molecules are immediately incorporated into thick filaments (Isaacs & Fulton, 1987). In fact, blocking myosin biosynthesis using a translation inhibitor significantly slows the substitution rate of myosin in myofibrils (Ojima, Ichimura, et al., 2015a). The secondary source is cytosolic myosin that is not incorporated into the thick filament. Reducing the level of cytosolic myosin using Streptolysin‐O, which perforates the plasma membrane to release cytosolic components such as myosin, leads to a lower myosin exchange rate (Ojima et al., 2017). These results also demonstrate that myosin allocated for replacement is present in the myocytosol, although myosin forms aggregates or filaments in physiological ionic conditions in vitro (Perry, 1955). In other words, the myosin exchange rate in thick filaments declines when myosin supply sources, including de novo synthesized myosin and pooled cytosolic myosin, are depleted.

1.6. Modulation of the myosin replacement rate by myosin chaperones

Heat shock proteins (HSP) are a family of molecular chaperones which assist in protein folding and remodeling, and are rapidly upregulated in response to cellular stressors. HSP90 is strongly implicated in thick filament organization (Smith, Carland, Guo, & Bernstein, 2014), with mutations or disrupted chaperone activity causing the disassembly of thick filaments in myofibrils (Du, Li, Bian, & Zhong, 2008; He, Liu, Tian, & Du, 2015). We investigated the effects of HSP90 on myosin substitution in thick filaments. HSP90 overexpression increased the rate of myosin replacement, while inhibiting its chaperone activity reduced myosin substitution in myofibrils, indicating that HSP90 chaperone activity is closely associated with myosin replacement (Ojima et al., 2018). As HSP90 was originally found to function as a chaperone to ensure the correct folding and conformational structure of myosin S1 (Srikakulam, Liu, & Winkelmann, 2008; Srikakulam & Winkelmann, 2004), its overexpression may increase the rate of myosin folding following translation, increasing the amount of myosin available for exchange. Upregulated MYH gene expression is also observed in myotubes overexpressing HSP90, alongside an increase in myosin content, however, the molecular mechanisms underlying the upregulation of MYH expression by HSP90 remain unclear.

What are the conditions in muscle cells overexpressing HSP90? The induction of HSP expression is an important response of skeletal muscle cells to physical exercise‐induced stress (Harris, Mitchell, Sood, Webb, & Venema, 2008; Locke, Noble, & Atkinson, 1990). Myofibrillar protein synthesis is also elevated in exercised skeletal muscle, supplying newly synthesized myofibrillar proteins to replace those damaged by exercise‐induced stress and to build new myofibrils in hypertrophy (Camera et al., 2015; Di Donato et al., 2014). Considering these findings, HSP90 overexpression may partly mimic the intracellular environment of exercised muscle, leading to the upregulation of myosin transcription, translation, and content in muscle cells. As a result, the myosin replacement rate may increase rapidly in myotubes overexpressing HSP90.

Uncoordinated mutant number 45 (UNC45) also functions as a chaperone for myosin (Barral, Hutagalung, Brinker, Hartl, & Epstein, 2002; Lee, Melkani, & Bernstein, 2014; Liu, Srikakulam, & Winkelmann, 2008; Srikakulam et al., 2008). UNC‐45 chain formation provides multiple HSP90 and myosin binding sites, with the correct spacing for myosin heads on thick filaments (Gazda et al., 2013). Although myofibril organization is impaired in Caenorhabditis elegans when UNC45 is overexpressed or knocked down (Landsverk et al., 2007), the myosin replacement rate is not affected in myotubes overexpressing UNC45b (Ojima et al., 2018).

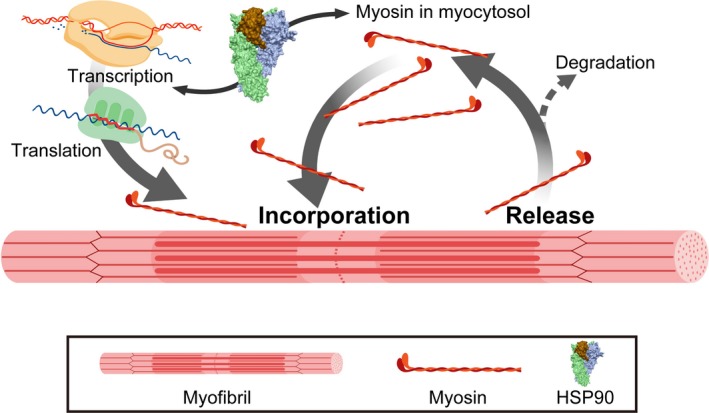

1.7. Proposed schematic model of myosin dynamics

Our proposed model of myosin dynamics in myofibers is illustrated in Figure 3. Newly synthesized myosin is immediately incorporated into the thick filament following translation (Isaacs & Fulton, 1987) while myosin is simultaneously released from the thick filament (Ojima, Ichimura, et al., 2015a). Myosin is pooled in the myocytosol, providing another source of replacement myosin. Although myosin forms aggregate under physiological ionic conditions in vitro (Perry, 1955), myosin is protected from aggregate formation in the myocytosol by an unknown mechanism. HSP90 induces the expression of MYH and subsequently increases the myosin content of the myocytosol, leading to rapid myosin replacement in thick filaments. Although damaged myosin is degraded by the ubiquitin‐proteasome system (Cohen et al., 2009; Fielitz et al., 2007), it is not yet known how and where damaged myosin is selected. The mechanisms of the myosin degradation system in this model should be investigated in future studies.

Figure 3.

Proposed myosin replacement model in myofibrils. Myosin in the thick filament is replaced by de novo synthesized and cytosolic myosin. In myosin exchange, the myosin released from the thick filament is retained in the myocytosol as recycled myosin, ready to be incorporated into the thick filament. Myosin shuttles between the thick filament and the myocytosol. HSP90 chaperone activity modulates the myosin substitution rate by upregulating MYH gene expression and increasing myosin content in the myocytosol. Future studies should highlight myosin degradation pathways. The figure was created using BioRender

2. CONCLUSION

Based on our current and previous experiments, we have described the role and the dynamics of myosin in the formation and maintenance of thick filament structure. Despite the collection of skeletal muscle data by multiple researchers, the dynamic control of myofibrillar proteins such as myosin is still poorly understood. How are hundreds of myofibrillar and myofibrillar‐associated proteins assembled into the highly ordered sarcomere structure? How do myofibers regulate, maintain, and degrade the myofibril structure at the molecular level? Importantly, these processes proceed without impeding muscle contraction. While sarcomeres appear to have a hard, rigid structure when observed using electron microscopy, each myofibrillar protein is continuously replaced. This is a crucial field for future research in animal science and life science in order to understand the fundamental regulation of plasticity and remodeling in the skeletal muscle of animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for the valuable support and fruitful discussions provided by Dr. Susumu Muroya, Dr. Mika Oe, Ms. Miho Ichimura, Ms. Chiho Shindo (National Institute of Livestock and Grass Sciences, NARO), and Prof. Takanori Nishimura (Hokkaido University). I thank Prof. emeritus Akihito Hattori (Hokkaido University) who provided the opportunity to collaborate in the early stages of the Myosin project. The author's research program was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS.KAKENHI. no. 22580301 and 16K08079) and the Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Ojima K. Myosin: Formation and maintenance of thick filaments. Anim Sci J. 2019;90:801–807. 10.1111/asj.13226

REFERENCES

- Atkinson, S. J. , & Stewart, M. (1991). Expression in Escherichia coli of fragments of the coiled‐coil rod domain of rabbit myosin: Influence of different regions of the molecule on aggregation and paracrystal formation. Journal of Cell Science, 99(Pt 4), 823–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral, J. M. , Hutagalung, A. H. , Brinker, A. , Hartl, F. U. , & Epstein, H. F. (2002). Role of the myosin assembly protein UNC‐45 as a molecular chaperone for myosin. Science, 295, 669–671. 10.1126/science.1066648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton‐Davis, E. R. , Shoturma, D. I. , Musaro, A. , Rosenthal, N. , & Sweeney, H. L. (1998). Viral mediated expression of insulin‐like growth factor I blocks the aging‐related loss of skeletal muscle function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 95, 15603–15607. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camera, D. M. , West, D. W. D. , Phillips, S. M. , Rerecich, T. , Stellingwerff, T. , Hawley, J. A. , & Coffey, V. G. (2015). Protein ingestion increases myofibrillar protein synthesis after concurrent exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47, 82–91. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , Brault, J. J. , Gygi, S. P. , Glass, D. J. , Valenzuela, D. M. , Gartner, C. , … Goldberg, A. L. (2009). During muscle atrophy, thick, but not thin, filament components are degraded by MuRF1‐dependent ubiquitylation. Journal of Cell Biology, 185, 1083–1095. 10.1083/jcb.200901052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R. , & Offer, G. (1976). Axial arrangement of crossbridges in thick filaments of vertebrate skeletal muscle. Journal of Molecular Biology, 102, 325–332. 10.1016/S0022-2836(76)80057-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps, R. M. , Suggs, J. A. , & Bernstein, S. I. (1999). Assembly of thick filaments and myofibrils occurs in the absence of the myosin head. EMBO Journal, 18, 1793–1804. 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Lopes, K. , Pietas, A. , Radke, M. H. , & Gotthardt, M. (2011). Titin visualization in real time reveals an unexpected level of mobility within and between sarcomeres. Journal of Cell Biology, 193, 785–798. 10.1083/jcb.201010099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasbiswas, K. , Hu, S. , Schnorrer, F. , Safran, S. A. , & Bershadsky, A. D. (2018). Ordering of myosin II filaments driven by mechanical forces: Experiments and theory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1747), 20170114– 10.1098/rstb.2017.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato, D. M. , West, D. W. , Churchward‐Venne, T. A. , Breen, L. , Baker, S. K. , & Phillips, S. M. (2014). Influence of aerobic exercise intensity on myofibrillar and mitochondrial protein synthesis in young men during early and late postexercise recovery. American Journal of Physiology‐Endocrinology and Metabolism, 306, E1025–1032. 10.1152/ajpendo.00487.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, S. J. , Li, H. , Bian, Y. , & Zhong, Y. (2008). Heat‐shock protein 90alpha1 is required for organized myofibril assembly in skeletal muscles of zebrafish embryos. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 105, 554–559. 10.1073/pnas.0707330105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A. G. , & Franzini‐Armstrong, C. (2004). Myology. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Fielitz, J. , Kim, M.‐S. , Shelton, J. M. , Latif, S. , Spencer, J. A. , Glass, D. J. , … Olson, E. N. (2007). Myosin accumulation and striated muscle myopathy result from the loss of muscle RING finger 1 and 3. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 117, 2486–2495. 10.1172/JCI32827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, L. , Pokrzywa, W. , Hellerschmied, D. , Lowe, T. , Forne, I. , Mueller‐Planitz, F. , … Clausen, T. (2013). The myosin chaperone UNC‐45 is organized in tandem modules to support myofilament formation in C. elegans . Cell, 152, 183–195. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokhin, D. S. , Kim, N. E. , Lewis, S. A. , Hoenecke, H. R. , D'Lima, D. D. , & Fowler, V. M. (2012). Thin‐filament length correlates with fiber type in human skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology, 302, C555–C565. 10.1152/ajpcell.00299.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio, C. C. , Granzier, H. , Sorimachi, H. , & Labeit, S. (1999). Muscle assembly: A titanic achievement? Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 11, 18–25. 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. B. , Mitchell, B. M. , Sood, S. G. , Webb, R. C. , & Venema, R. C. (2008). Increased nitric oxide synthase activity and Hsp90 association in skeletal muscle following chronic exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 104, 795–802. 10.1007/s00421-008-0833-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Q. , Liu, K. , Tian, Z. , & Du, S. J. (2015). The effects of Hsp90alpha1 mutations on myosin thick filament organization. PLoS ONE, 10, e0142573 10.1371/journal.pone.0142573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, C. A. , Gomez, C. G. , Novak, S. M. , Mi‐Mi, L. , & Gregorio, C. C. (2017). Overview of the muscle cytoskeleton. Comprehensive Physiology, 7, 891–944. 10.1002/cphy.c160033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowits, R. , Kempner, E. S. , Bisher, M. E. , & Podolsky, R. J. (1986). A physiological role for titin and nebulin in skeletal muscle. Nature, 323, 160–164. 10.1038/323160a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S. , Dasbiswas, K. , Guo, Z. , Tee, Y.‐H. , Thiagarajan, V. , Hersen, P. , … Bershadsky, A. D. (2017). Long‐range self‐organization of cytoskeletal myosin II filament stacks. Nature Cell Biology, 19, 133–141. 10.1038/ncb3466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, H. E. (1963). Electron microscope studies on the structure of natural and synthetic protein filaments from striated muscle. Journal of Molecular Biology, 7, 281–308. 10.1016/S0022-2836(63)80008-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving, M. (2017). Regulation of contraction by the thick filaments in skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal, 113, 2579–2594. 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, W. B. , & Fulton, A. B. (1987). Cotranslational assembly of myosin heavy chain in developing cultured skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 84, 6174–6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit, S. , & Kolmerer, B. (1995). Titins: Giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity. Science, 270, 293–296. 10.1126/science.270.5234.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk, M. L. , Li, S. , Hutagalung, A. H. , Najafov, A. , Hoppe, T. , Barral, J. M. , & … H. F. (2007). The UNC‐45 chaperone mediates sarcomere assembly through myosin degradation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Cell Biology, 177, 205–210. 10.1083/jcb.200607084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. F. , Melkani, G. C. , & Bernstein, S. I. (2014). The UNC‐45 myosin chaperone: From worms to flies to vertebrates. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology, 313, 103–144. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800177-6.00004-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield, R. , Almenar‐Queralt, A. , & Fowler, V. M. (2001). Actin dynamics at pointed ends regulates thin filament length in striated muscle. Nature Cell Biology, 3, 544–551. 10.1038/35078517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. , Srikakulam, R. , & Winkelmann, D. A. (2008). Unc45 activates Hsp90‐dependent folding of the myosin motor domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283, 13185–13193. 10.1074/jbc.M800757200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke, M. , Noble, E. G. , & Atkinson, B. G. (1990). Exercising mammals synthesize stress proteins. American Journal of Physiology, 258, C723–729. 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.4.C723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther, P. K. , Munro, P. M. , & Squire, J. M. (1981). Three‐dimensional structure of the vertebrate muscle A‐band. III. M‐region structure and myosin filament symmetry. Journal of Molecular Biology, 151, 703–730. 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90430-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, K. (1976). Connectin, an elastic protein from myofibrils. Journal of Biochemistry, 80, 405–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, I. R. , & Mueller, H. (1966). The metabolism of myosin and the meromyosins from rabbit skeletal muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 241, 5967–5973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron, A. C. , Lawler, A. M. , & Lee, S. J. (1997). Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF‐beta superfamily member. Nature, 387, 83–90. 10.1038/387083a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. K. , Bang, M.‐L. , Witt, C. C. , Labeit, D. , Trombitas, C. , Watanabe, K. , … Labeit, S. (2003). The muscle ankyrin repeat proteins: CARP, ankrd2/Arpp and DARP as a family of titin filament‐based stress response molecules. Journal of Molecular Biology, 333, 951–964. 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. S. , Dambacher, C. M. , Knowles, A. F. , Braddock, J. M. , Farman, G. P. , Irving, T. C. , … Maughan, D. W. (2009). Alternative S2 hinge regions of the myosin rod affect myofibrillar structure and myosin kinetics. Biophysical Journal, 96, 4132–4143. 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncman, C. L. , Rindt, H. , Robbins, J. , & Winkelmann, D. A. (1993). Segregated assembly of muscle myosin expressed in nonmuscle cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4, 1051–1067. 10.1091/mbc.4.10.1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhre, J. L. , Hills, J. A. , Prill, K. , Wohlgemuth, S. L. , & Pilgrim, D. B. (2014). The titin A‐band rod domain is dispensable for initial thick filament assembly in zebrafish. Developmental Biology, 387, 93–108. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki, I. (1979). Number of anti‐troponin striations along the thin filament of chick embryonic breast muscle. Journal of Biochemistry, 85, 1377–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, K. , Ichimura, E. , Suzuki, T. , Oe, M. , Muroya, S. , & Nishimura, T. (2018). HSP90 modulates the myosin replacement rate in myofibrils. American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology, 315, C104–114. 10.1152/ajpcell.00245.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, K. , Ichimura, E. , Yasukawa, Y. , Oe, M. , Muroya, S. , Suzuki, T. , … Nishimura, T. (2017). Myosin substitution rate is affected by the amount of cytosolic myosin in cultured muscle cells. Animal Science Journal, 88, 1788–1793. 10.1111/asj.12826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, K. , Ichimura, E. , Yasukawa, Y. , Wakamatsu, J. , & Nishimura, T. (2015a). Dynamics of myosin replacement in skeletal muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology, 309, C669–679. 10.1152/ajpcell.00170.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, K. , Kawabata, Y. , Nakao, H. , Nakao, K. , Doi, N. , Kitamura, F. , … Sorimachi, H. (2010). Dynamic distribution of muscle‐specific calpain in mice has a key role in physical‐stress adaptation and is impaired in muscular dystrophy. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 120, 2672–2683 10.1172/JCI40658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, K. , Oe, M. , Nakajima, I. , Shibata, M. , Muroya, S. , Chikuni, K. , … Nishimura, T. (2015b). The importance of subfragment 2 and C‐terminus of myosin heavy chain for thick filament assembly in skeletal muscle cells. Animal Science Journal, 86, 459–467. 10.1111/asj.12310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, S. , Jurgens, K. D. , & Gros, G. (2000). Protein diffusion in living skeletal muscle fibers: Dependence on protein size, fiber type, and contraction. Biophysical Journal, 79, 2084–2094. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76456-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, S. V. (1955). Myosin adenosinetriphosphatase. Methods in Enzymology, 2, 582–588. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow, D. I. , Deacon, J. C. , Warrick, H. M. , Spudich, J. A. , & Leinwand, L. A. (2010). Functional diversity among a family of human skeletal muscle myosin motors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 107, 1053–1058. 10.1073/pnas.0913527107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, N. , Chi, J. , & Holtzer, H. (1976). Coordinated synthesis and degradation of actin and myosin in a variety of myogenic and non‐myogenic cells. Experimental Cell Research, 97, 387–393. 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90630-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, J. R. (2000). Myosins: A diverse superfamily. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1496, 3–22. 10.1016/S0167-4889(00)00005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. A. , Carland, C. R. , Guo, Y. , & Bernstein, S. I. (2014). Getting folded: Chaperone proteins in muscle development, maintenance and disease. Anatomical Record, 297, 1637–1649. 10.1002/ar.22980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, R. L. , Vikstrom, K. L. , Strauss, M. , Cohen, C. , Szent‐Gyorgyi, A. G. , & Leinwand, L. A. (1997). A 29 residue region of the sarcomeric myosin rod is necessary for filament formation. Journal of Molecular Biology, 266, 317–330. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikakulam, R. , Liu, L. , & Winkelmann, D. A. (2008). Unc45b forms a cytosolic complex with Hsp90 and targets the unfolded myosin motor domain. PLoS ONE, 3, e2137 10.1371/journal.pone.0002137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikakulam, R. , & Winkelmann, D. A. (2004). Chaperone‐mediated folding and assembly of myosin in striated muscle. Journal of Cell Science, 117, 641–652. 10.1242/jcs.00899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suggs, J. A. , Cammarato, A. , Kronert, W. A. , Nikkhoy, M. , Dambacher, C. M. , Megighian, A. , & Bernstein, S. I. (2007). Alternative S2 hinge regions of the myosin rod differentially affect muscle function, myofibril dimensions and myosin tail length. Journal of Molecular Biology, 367, 1312–1329. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, H. L. , & Hammers, D. W. (2018). Muscle Contraction. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 10 10.1101/cshperspect.a023200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. C. , Buvoli, M. , Buvoli, A. , & Leinwand, L. A. (2012). Myosin filament assembly requires a cluster of four positive residues located in the rod domain. FEBS Letters, 586, 3008–3012. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonino, P. , Kiss, B. , Strom, J. , Methawasin, M. , Smith, J. E. , Kolb, J. , … Granzier, H. (2017). The giant protein titin regulates the length of the striated muscle thick filament. Nature Communications, 8, 1041 10.1038/s41467-017-01144-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombitas, K. , Redkar, A. , Centner, T. , Wu, Y. , Labeit, S. , & Granzier, H. (2000). Extensibility of isoforms of cardiac titin: Variation in contour length of molecular subsegments provides a basis for cellular passive stiffness diversity. Biophysical Journal, 79, 3226–3234. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76555-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikstrom, K. L. , Seller, S. H. , Sohn, R. L. , Strauss, M. , Weiss, A. , Welikson, R. E. , & Leinwand, L. A. (1997). The vertebrate myosin heavy chain: Genetics and assembly properties. Cell Structure and Function, 22, 123–129. 10.1247/csf.22.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Fan, Y. , Dube, D. K. , Sanger, J. M. , & Sanger, J. W. (2014). Jasplakinolide reduces actin and tropomyosin dynamics during myofibrillogenesis. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken), 71, 513–529. 10.1002/cm.21189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Shaner, N. , Mittal, B. , Zhou, Q. , Chen, J. U. , Sanger, J. M. , & Sanger, J. W. (2005). Dynamics of Z‐band based proteins in developing skeletal muscle cells. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton, 61, 34–48. 10.1002/cm.20063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. , McClure, J. , & Tu, A. (1979). Titin: Major myofibrillar components of striated muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 76, 3698–3702. 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeds, A. G. , & Lowey, S. (1971). Substructure of the myosin molecule. II. The light chains of myosin. Journal of Molecular Biology, 61, 701–725. 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates, L. D. , & Greaser, M. L. (1983). Quantitative determination of myosin and actin in rabbit skeletal muscle. Journal of Molecular Biology, 168, 123–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak, R. , Martin, A. F. , Prior, G. , & Rabinowitz, M. (1977). Comparison of turnover of several myofibrillar proteins and critical evaluation of double isotope method. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 252, 3430–3435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]