Abstract

Introduction:

Individuals with diabetes are at particularly at high risk for many of the negative health consequences associated with influenza and pneumococcal infections. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination among a population of type 2 diabetic patients in Saudi Arabia and to determine the factors associated with vaccine uptake.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among patients with type 2 diabetes at Security Forces Hospital, Riyadh in Saudi Arabia. The survey asked basic demographic questions as well as questions about awareness, vaccination status, and beliefs about the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines.

Results:

From a total number of 422 responses, 360 participants were ultimately included in the final sample. The overall prevalence of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in this population were 47.8% and 2.8%, respectively. In general, there was a very low awareness of the pneumococcal vaccine. Older individuals, unmarried individuals, those with less education, and those living with certain chronic conditions were less likely to have gotten the influenza vaccine. Beliefs in the importance of vaccination for people with diabetes, the efficacy of the influenza vaccine, and not being worried about the side effect of the vaccine were strongly associated with having received the vaccine.

Conclusions:

Attention should be given to increasing awareness of the pneumococcal vaccine among people living with diabetes. Particular consideration should also be paid to increasing access and awareness to both vaccines among those groups that have the lowest prevalence of vaccination and may be at the highest risk for the negative consequences associated with these infections. Finally, education interventions should be used to increase the understanding of the safety and efficacy of the influenza vaccine.

Keywords: Adult, diabetes mellitus, influenza vaccine, pneumococcal vaccine

Introduction

Diabetic people are vulnerable to influenza and pneumonia. However, they can take vaccines to protect themselves from being affected even after being exposed to the viruses. It is, therefore, important to identify whether diabetic people in Saudi Arabia take advantages of these vaccines, especially during the most vulnerable seasons. Saudi Arabia has one of the highest prevalence of diabetes compared to other countries. Statistics reveal that 23.9% of the population is diabetic.[1,2] Records also show that the prevalence of morbidities related to diabetes among diabetics includes 82% with neuropathy, 32% with nephropathy, and 31% with retinopathy.[3]

Diabetic patients with pneumonia are at higher mortality risk than others.[4] There are no specific local records indicating mortality and morbidity rates for diabetic people with influenza or pneumonia. However, hospital and ICU mortality rates of community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia are 24.4% and 30.3%, respectively.[5] Additionally, other records show that influenza and pneumonia have a cumulative mortality rate of 44.89%.[6] Due to such susceptibility, the American Diabetes Association and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommend that diabetic people should receive influenza vaccines on an annual basis.[7,8] These are provided seasonally due to the ever-changing nature of influenza virus's antigens.[9] Additionally, the pneumococcal vaccine is recommended to be given at least once in a lifetime.[7,10]

Saudi Arabia is treated as a special case for vaccination due to the Hajj and Umrah seasons, which attract millions of people from across the globe, thus heightening the risk of acquiring influenza significantly.[11] The weak nature of diabetic patients increases their risk of acquiring influenza even higher as compared to a non-diabetic person or a person who does not have any chronic illness.

Studies show that the average vaccine uptake for a Saudi Arabian is 15%, which is lower than that of other Gulf countries such as Qatar, whose rate is 24%.[12] However, people who were at a higher risk of getting these diseases had a pneumococcal vaccine uptake of 25%.[12]

Diabetes is also widely ignored as an indicator for influenza and pneumococcal vaccines unless there is the presence of another indicator.[13] Lack of awareness about the vaccine was the main reason given by many patients for not having been immunized.[14,15,16] Low income has also been documented among those who were not immunized. Additionally, diabetic patients with access to proper finances are better placed to receive care from physicians and also benefit from the advice and recommendations from such specialists.[15] The majority of vaccinated individuals received advice from primary care physicians.[14,15,16,17]

There is a need to conduct this study to determine the prevalence of the uptake of these two vaccinations and the predictors of this uptake. Additionally, there is little information available about the uptake of vaccinations among vulnerable groups in the region, such as those with diabetes.

The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake in Saudi type 2 diabetic individuals who are attending a routine out-patient appointment at family medicine department. Additionally, this study seeks to determine the predictors that may influence the likelihood of vaccine uptake in Saudi type 2 diabetic individuals.

Materials and Methods

Sample size

The estimated prevalence of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake was reported in the literature as 64.5% and 22.0%. In order to detect these prevalences with a probability of type 2 error at 0.05 and a probability of type 1 error at 0.20, it was determined that 352 study subjects would be required. Anticipating 10% non-response, the study aimed to sample at least 387 individuals.

Population and data collection

The inclusion criteria for the study were being a Saudi males or female with type 2 diabetes who attended a routine out-patient appointment in the family medicine department at Security Forces Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between October and December 2018. Exclusion criteria for the study were having type 1 or had gestational diabetes, cognitive impairment, or splenectomy, reporting being allergic to vaccines, or having missing data for any of the variables included in the final analysis.

The participants filled in a written consent form to ensure that participation in the study was voluntary. The participants had the option to drop out from the study at any time. The purpose of the study and the estimated time it would take to complete the questionnaire was explained to each participant. Confidentiality was assured by assigning each patient a medical record number. The name and the email of the researcher was written on the first page of the questionnaire in case patients had any further questions about the survey.

The questionnaire included 3 sections. The first section aimed to gather demographic data about the population. The second and the third sections assessed the vaccines uptake status, and patients’ opinions and beliefs about the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines.

Statistical analysis

SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform all analysis. We generated frequencies and percentages for the demographic variables and variables related to the participants’ beliefs about the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. The prevalence rates of influenza vaccine uptake were calculated by these same demographic factors and beliefs about the influenza vaccine. We did so in order to determine whether any of these factors related to the probability of having received an influenza vaccine. Poisson regression with a log link was used to calculate the prevalence rate ratios of influenza vaccinations according to these demographic factors and beliefs about the vaccine. Univariate analysis was done for all variables. Among the demographic variables, an additional multivariate analysis was performed in which all demographic variables were modelled simultaneously. Prevalence rates were not calculated for pneumococcal vaccination according to demographic factors and beliefs because of the low prevalence of pneumococcal vaccination in this population.

Results

There were a total of 422 individuals who participated in the survey. Among these participants, 12 were excluded because they reported having allergies that made them unable to get vaccinated. An additional 54 participants were excluded because they were missing responses to at least one of the variables used in this analysis. This resulted in a final same of 360 participants who were not allergic to vaccines and had no missing data.

As shown in Table 1, most participants were 50 to 59 years old (122, 33.9%) or 60 or older (96, 26.7%). Fewer participants were younger than 50. There were only slightly more females (188, 52.2%) in the sample compared to males (172, 47.8%). Those who reported having a high school education or less (162, 45.0%) or being illiterate (126, 35.0%) made up the majority of the participants. The remainder had a college education. A large majority of the sample were married (288, 80.0%) with fewer reporting being single (32, 8.9%) or divorced or widowed (40, 11.1%). Most participants reporting having no chronic conditions other than diabetes (260, 72.2%). Among those with chronic conditions, the most frequently reported were chronic heart disease (58, 16.1%), chronic lung disease (26, 7.2%), and chronic kidney disease (8, 2.2%). Fewer participants reported chronic liver disease, sickle cell disease, or having a suppressed immune system. The majority of the respondents were not taking insulin (282, 78.3%).

Table 1.

Demographics, health behaviors, and health conditions of study populations, n=360

| Frequency (Percent) | |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 30-39 | 50 (13.9) |

| 40-49 | 92 (25.6) |

| 50-59 | 122 (33.9) |

| 60 or older | 96 (26.7) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 188 (52.2) |

| Male | 172 (47.8) |

| Level of education | |

| Illiterate | 126 (35.0) |

| High school or less | 162 (45.0) |

| College education | 72 (20.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 288 (80.0) |

| Single | 32 (8.9) |

| Divorced or widowed | 40 (11.1) |

| Smoking status | |

| Non-smoker | 274 (76.1) |

| Smoker | 56 (15.6) |

| Former smoker | 30 (8.3) |

| Chronic conditions | |

| Chronic heart disease | 58 (16.1) |

| Chronic lung disease | 26 (7.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (2.2) |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 (1.1) |

| Sickle cell disease | 2 (0.6) |

| Suppressed immune system | 2 (0.6) |

| None | 260 (72.2) |

| Insulin status | |

| Taking insulin | 74 (20.6) |

| Not taking insulin | 282 (78.3) |

| Doesn’t know if taking insulin | 4 (1.1) |

As shown in Table 2, most respondents were aware of the Influenza vaccine (236, 65.6%). The prevalence of influenza vaccination in this population was 47.8% with 172 participants being vaccinated. Half of the participants did not know whether it is important for those with diabetes to get the influenza vaccine (180, 50.0%). Among those with an opinion, most believed that it was important (136, 37.8%). Most participants either believed that the Influenza vaccine works in preventing the flu (164, 45.6%) or did not know (152, 42.2%). Most participants (274, 76.1%) reported that they had enough time to get the influenza vaccine. Only 6 (1.7%) participants reported not having enough time to get the Influenza vaccine. Most participants were not worried about the side effect of the Influenza vaccine (212, 58.9%), compared to only 44 (12.2%) participants who were worried about side effects. Most participants were not worried that the influenza vaccine would be painful (210, 58.3%), compared to only 56 (15.6%) participants who were worried that the vaccine would be painful.

Table 2.

Influenza vaccination status and beliefs about the vaccine, n=360

| Frequency (Percent) | |

|---|---|

| Are you aware of the influenza vaccine (i.e. the “flu jab”)? | |

| Yes | 236 (65.6) |

| No | 124 (34.4) |

| Have you ever had an influenza vaccination? | |

| Yes | 172 (47.8) |

| No | 186 (51.7) |

| Don’t know | 2 (0.6) |

| It is important for people with diabetes to get the influenza vaccine. | |

| Yes | 136 (37.8) |

| No | 44 (12.2) |

| Don’t know | 180 (50.0) |

| The influenza vaccine works in preventing the flu. | |

| Yes | 164 (45.6) |

| No | 44 (12.2) |

| Don’t know | 152 (42.2) |

| I don’t have enough time to get the influenza vaccine. | |

| Yes | 6 (1.7) |

| No | 274 (76.1) |

| Don’t know | 80 (22.2) |

| I am worried about side effects of the influenza vaccine. | |

| Yes | 44 (12.2) |

| No | 212 (58.9) |

| Don’t know | 104 (28.9) |

| I am worried that the influenza vaccine may be painful | |

| Yes | 56 (15.6) |

| No | 210 (58.3) |

| Don’t know | 94 (26.1) |

As shown in Table 3, there was very low awareness of the pneumococcal vaccine, with 336 (93.3%) participants reporting that they were not aware of it. Similarly, 338 (93.9%) of participants reported not receiving the pneumococcal vaccine. Therefore the uptake of the pneumococcal vaccine in this population was 2.8%. Most participants reported that they did not know if it was important for those with diabetes to get the pneumococcal vaccine (320, 88.9%). Among those with an opinion, 24 (6.7%) respondents thought it is important and 16 (4.4%) respondents thought that it is not important. A large majority of participants reported that they did not know if the pneumococcal vaccine worked in preventing pneumococcal infections (316, 87.8%). Among those with an opinion, 30 (8.3%) reported believing that the vaccine works in preventing pneumococcal infections and 14 (3.9%) report believing that it does not work. Most participants reported not having enough time to get the pneumococcal vaccine (248, 68.9%) or not knowing if they had enough time (108, 30.0%). A majority of participants reported not knowing if they were worried about side effects from the pneumococcal vaccine (246, 68.3%). Among those with an opinion, most reported that they were not worried (76, 21.1%). 38 (10.6%) participants reported that they were worried. Similarly, most respondents reported that they did not know if they were worried that the pneumococcal vaccine may be painful (264, 73.3%). Among those with an opinion, most reported that they were not worried (68, 18.9). 28 (7.8%) of respondents reported that they were worried about the vaccine being painful.

Table 3.

Pneumococcal vaccination status and beliefs about the vaccine, n=360

| Frequency (Percent) | |

|---|---|

| Are you aware of the pneumococcal vaccine (i.e. the vaccine against pneumonia and other illnesses)? | |

| Yes | 24 (6.7) |

| No | 336 (93.3) |

| Have you ever had a pneumococcal vaccine? | |

| Yes | 10 (2.8) |

| No | 338 (93.9) |

| Don’t know | 12 (3.3) |

| It is important for people with diabetes to get the pneumococcal. | |

| Yes | 24 (6.7) |

| No | 16 (4.4) |

| Don’t know | 320 (88.9) |

| The pneumococcal vaccine works in preventing the pneumococcal disease. | |

| Yes | 30 (8.3) |

| No | 14 (3.9) |

| Don’t know | 316 (87.8) |

| I don’t have enough time to get the pneumococcal vaccine. | |

| Yes | 4 (1.1) |

| No | 248 (68.9) |

| Don’t know | 108 (30.0) |

| I am worried about side effects of the pneumococcal vaccine. | |

| Yes | 38 (10.6) |

| No | 76 (21.1) |

| Don’t know | 246 (68.3) |

| I am worried that the pneumococcal vaccine may be painful. | |

| Yes | 28 (7.8) |

| No | 68 (18.9) |

| Don’t know | 264 (73.3) |

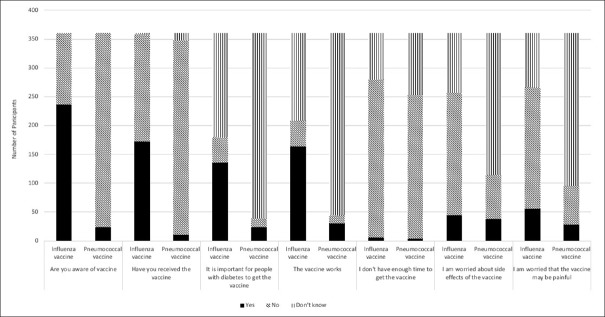

Figure 1 shows a comparison between the participants’ behaviors and beliefs about the influenza and the pneumococcal vaccines. Awareness and uptake of the vaccine were much higher for the influenza vaccine compared to the pneumococcal vaccine. For almost all of the belief questions, most respondents reported not knowing when responding to questions about the pneumococcal vaccine, while most respondents had opinions about the influenza vaccine.

Figure 1.

A comparison between the participants’ behaviors and beliefs about the influenza and the pneumococcal vaccines

As shown in Table 4, when the prevalence of influenza vaccine uptake was stratified by ten year age groups, the highest prevalence was among those in the 30-39 year age group (80.0, 95% CI: 55.2, 100.0). The prevalence of influenza vaccination showed an inverse relationship with age. Each age groups’ prevalence rate that was lower than that of the 30-39 year old age group with the lowest prevalence among those 60 or older (27.1, 95% CI: 16.7, 37.5). The prevalence rate ratios comparing the differences in prevalence rates between those in the 30 to 39 age group to the other age groups was statistically significant in the univariate model, but were not statistically significant in the multivariate model. Although females (50.0, 95% CI: 39.9, 60.1) had a higher prevalence rate compared to males (45.3, 95% CI: 35.3, 55.4), this difference was not statistically significant in both the univariate and multivariate models. The prevalence of influenza vaccination was highest among those with a college education (86.1, 95% CI: 64.7, 100.0). The prevalence of influenza vaccination among those with a high school education or less (42.0, 95% CI: 32.0, 52.0) and those who were illiterate (33.3, 95% CI: 23.3, 43.4) was lower than that among those with a college education. These differences were statistically significant in both the univariate and multivariate models. Married participants had the highest prevalence of influenza vaccination (54.2, 95%: 45.7, 62.7). Although the prevalence was lower among those who were single (37.5, 95% CI: 16.3, 58.7), this difference was not statistically significant in either the univariate or multivariate models. However, the difference in the prevalence between those who were divorced or widowed (10.0, 95% CI: 0.2, 19.8) and married was statistically significant in both the univariate and multivariate models.

Table 4.

Prevalence of influenza vaccination by demographics, health behaviors, and health conditions of study populations, n=360

| Number Reporting being vaccinated | Percentage vaccinated (95% Confidence Interval) | Univariate Prevalence Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)1 | P | Multivariate prevalence rate ratio (95% Confidence Interval)2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 172 | 47.8 (40.6, 54.9) | ||||

| Age group | ||||||

| 30-39 | 40 | 80.0 (55.2, 100.0) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 40-49 | 46 | 50.0 (35.6, 64.4) | 0.63 (0.41, 0.95) | 0.0297 | 0.70 (0.42) | 0.1779 |

| 50-59 | 60 | 49.2 (36.7, 61.6) | 0.61 (0.41, 0.92) | 0.0171 | 0.96 (0.55, 1.67) | 0.8726 |

| 60 or older | 26 | 27.1 (16.7, 37.5) | 0.34 (0.21, 0.55) | <0.0001 | 0.58 (0.30, 1.12) | 0.1046 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 94 | 50.0 (39.9, 60.1) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Male | 78 | 45.3 (35.3, 55.4) | 0.91 (0.67, 1.22) | 0.5238 | 0.97 (0.63, 1.48) | 0.8760 |

| Level of education | ||||||

| College education | 62 | 86.1 (64.7, 100.0) | 1 (ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| High school or less | 68 | 42.0 (32.0, 52.0) | 0.49 (0.35, 0.69) | <0.0001 | 0.52 (0.34, 0.81) | 0.0218 |

| Illiterate | 42 | 33.3 (23.3, 43.4) | 0.39 (0.26, 0.57) | <0.0001 | 0.53 (0.31, 0.91) | 0.0033 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 132 | 54.2 (45.7, 62.7) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Divorced or widowed | 36 | 10.0 (0.2, 19.8) | 0.18 (0.07, 0.50) | 0.0008 | 0.23 (0.08, 0.67) | 0.0068 |

| Single | 18 | 37.5 (16.3, 58.7) | 0.69 (0.38, 1.25) | 0.2196 | 0.62 (0.33, 1.18) | 0.1428 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Non-smoker | 130 | 51.8 (43.3, 60.3) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Smoker | 36 | 35.7 (20.1, 51.4) | 0.69 (0.43, 1.10) | 0.119 | 0.75 (0.42, 1.36) | 0.3446 |

| Former smoker | 20 | 33.3 (12.7, 54.0) | 0.64 (0.34, 1.22) | 0.1774 | 0.60 (0.29, 1.24) | 0.1719 |

| Chronic conditions | ||||||

| None | 122 | 52.3 (43.5, 61.1) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 40 | 31.0 (16.7, 45.4) | 0.59 (0.36, 0.97) | 0.0374 | 0.90 (0.53, 1.53) | 0.7004 |

| Chronic lung disease | 20 | 23.1 (4.6, 41.5) | 0.44 (0.19, 1.00) | 0.0498 | 0.45 (0.19, 1.04) | 0.0627 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 | 50.0 (1.0, 99.0) | 0.96 (0.35, 2.58) | 0.9291 | 1.62 (0.57, 4.56) | 0.3643 |

| Insulin status | ||||||

| Taking insulin | 30 | 59.5 (41.9, 77.0) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Not taking insulin | 154 | 44.7 (36.9, 52.5) | 0.75 (0.53, 1.06) | 0.1027 | 0.60 (0.41, 0.88) | 0.0099 |

| Doesn’t know if taking insulin | 2 | 50.0 (0.0, 100.0) | 0.84 (0.20, 3.47) | 0.8106 | 0.50 (0.12, 2.20) | 0.3616 |

1 - Each variable analyzed separately. 2 - Including all variables in table

Table 4 also shows that although both smokers (35.7, 95% CI: 20.1, 51.4) and former smokers (33.3, 95% CI: 12.7, 54.0) had lower prevalence rates of influenza vaccination compared to non-smokers (51.8, 95% CI: 43.3, 60.3), these differences were not statistically significant in either the univariate or multivariate models. Those without any chronic conditions had the highest prevalence of influenza vaccination (31.0, 95% CI: 16.7, 45.4), while those with chronic heart disease (31.0, 95% CI: 16.7, 45.4), chronic lung disease (23.1, 95% CI: 4.6, 41.5), and chronic kidney disease (50.0 95% CI: 1.0, 99.0) had lower rates. With respect to chronic heart disease and chronic lung disease, the difference was statistically significant in the univariate, but not the multivariate model. However, the P value for chronic lung disease was only slightly higher than 0.05 in the multivariate model. Those who were taking insulin (59.5, 95% CI: 41.9, 77.0) had a higher prevalence of influenza vaccination compared to those who were not (44.7, 95% CI: 36.9, 52.5) and those who did not know if they were taking insulin (50.0, 95% CI: 0.0, 100.0). The difference between those taking and not taking insulin was not statistically significant in the univariate model but was statistically significant in the multivariate model.

As shown in Table 5, the prevalence rate of influenza vaccination was substantially and significantly higher among those who believe that it is important for people with diabetes to get the influenza vaccine (83.8, 95% CI: 68.4, 99.2) compared to those who said that it is not important (18.6, 95% CI: 2.7, 24.5) or reported that they did not know (28.9, 95% CI: 21.0, 36.7). In a similar way, the prevalence of influenza vaccination was substantially and significantly higher among those who think that the influenza vaccine works in preventing the influenza (72.0, 95% CI: 59.0, 84.9) compared to those who said that it does not work (27.3 95% CI: 11.8, 42.7) or reported that they did not know (27.3, 95% CI: 19.3, 36.0). Nobody who reported not having enough time to get vaccinated had received the influenza vaccine. Those who reported that they did have a high enough time (49.6, 95% CI: 41.3, 58.0) or did not know if they had enough time (45.0, 95% CI: 30.3, 59.7) had a similar prevalence rate of influenza vaccination. Those who reported that they were worried about side effects from the influenza vaccine (18.2, 95% CI: 5.6, 30.8) were substantially and significantly less likely to be vaccinated compared to those who were not worried about side effects (61.3, 95% CI: 50.8, 71.9). Although those who did not know if they were worried had a higher prevalence (32.7, 95% CI: 21.7, 43.7), this difference was not statistically significant. Those who reported that they were worried that the influenza vaccine would be painful (43.9, 95% CI: 25.7, 60.0) had a lower rate of vaccination compared to those who were not worried (60.0, 95% CI: 49.5, 70.5), but this difference was not statistically significant. Those who reported not knowing if they were worried, had the lowest prevalence of vaccination (23.4, 95% CI: 13.6, 33.2) and this prevalence was statistically significantly lower than that for those who were worried about the vaccine being painful.

Table 5.

Prevalence of influenza vaccination by beliefs about the vaccine, n=360

| Number Reporting being vaccinated | Percentage vaccinated (95% Confidence Interval) | Univariate Prevalence Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)1 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 172 | 47.8 (40.6, 54.9) | ||

| It is important for people with diabetes to get the influenza vaccine. | ||||

| Yes | 114 | 83.8 (68.4, 99.2) | 1 (ref) | |

| No | 6 | 18.6 (2.7, 24.5) | 0.16 (0.07, 0.37) | <0.0001 |

| Don’t know | 52 | 28.9 (21.0, 36.7) | 0.34 (0.25, 0.48) | <0.0001 |

| The influenza vaccine works in preventing the flu. | ||||

| Yes | 118 | 72.0 (59.0, 84.9) | 1 (ref) | |

| No | 12 | 27.3 (11.8, 42.7) | 0.38 (0.21, 0.69) | 0.0014 |

| Don’t know | 42 | 27.3 (19.3, 36.0) | 0.38 (0.27, 0.55) | <0.0001 |

| I don’t have enough time to get the influenza vaccine. | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 2 | 2 |

| No | 136 | 49.6 (41.3, 58.0) | 2 | 2 |

| Don’t know | 36 | 45.0 (30.3, 59.7) | 2 | 2 |

| I am worried about side effects of the influenza vaccine. | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 18.2 (5.6, 30.8) | 1 (ref) | |

| No | 130 | 61.3 (50.8, 71.9) | 3.37 (1.65, 6.89 | 0.0008 |

| Don’t know | 34 | 32.7 (21.7, 43.7) | 1.80 (0.83, 3.88) | 0.1354 |

| I am worried that the pneumococcal vaccine may be painful. | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 43.9 (25.7, 60.0) | 1 (ref) | |

| No | 126 | 60.0 (49.5, 70.5) | 1.40 (0.90, 2.17) | 0.1309 |

| Don’t know | 22 | 23.4 (13.6, 33.2) | 0.55 (0.32, 0.97) | 0.0404 |

1 - Each variable analyzed separately. 2 - Insufficient sample size to calculate

Discussion

Among Saudis with Type 2 Diabetes who were attending a routine out-patient appointment in family medicine department, the prevalence of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination were 47.8% and 2.8%, respectively. These prevalence are lower than what was expected from the literature, which had shown influenza and pneumococcal vaccination prevalence rate of 64.5% and 22.0%, respectively. This is a concern because diabetics are at a higher risk of negative health outcomes if they have influenza or pneumococcal infections.[4]

These findings suggest that younger participants were more likely to be vaccinated compared to older participants. This result is not consistent with two other studies from the United States, which found that the both influenza and pneumococcal vaccination uptake was higher among participants 65 or older.[18,19] One study conducted in the United States found that those with chronic conditions were less likely to get vaccinated.[19] Another study conducted in multiple European countries found that in some countries those with certain chronic diseases were less likely to be vaccinated, but in other countries, they were more likely to be vaccinated.[20] The findings that older individuals and those with chronic conditions in this population were less likely to be vaccinated is concerning because they may be at a higher risk for negative health outcomes if they contract influenza.[21] Older individuals and those with chronic conditions may be concerned about their vulnerability to negative health outcomes associated with vaccination, which may reduce their probability of vaccination.

The fact that more educated participants had a higher prevalence of vaccination is consistent with at least one previous study.[22] There are at least 2 factors that may account for these differences. First, because education is often associated with employment and income, less educated individuals may have fewer resources to afford vaccination. It has been shown that access to proper finances is associated with a high probability of vaccination.[13] Additionally, less educated individuals may not be as informed about the benefits of vaccination compared to those with more education. The finding that married individuals were more likely to be vaccinated compared to those who were not married is consistent with at least one previous study, that found that married nurses were more likely to have had the influenza vaccine compared to unmarried nurses.[23] It may be the case that married individuals are more likely to be vaccinated because of concerns about infecting their spouse or being infected by their spouse. Additionally, it may be the case that spouses may compel each other to get medical care that they would not get if they were not married. For example, one study found that married men were more likely to have had at least one medical visit in the past year compared to unmarried men.[24]

Consistent with the Health Belief Model[25], the beliefs of patients about their susceptibility to influenza, its severity, and the harms and barriers associated with influenza and the influenza vaccine were strongly associated with the prevalence of vaccination. At least 2 previous studies have generated strong connections between beliefs about vaccination and vaccination uptake.[19,20]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted to calculate the vaccination rates for influenza and pneumococcal vaccines among type 2 diabetics in Saudi Arabia. The findings from this study can be useful as a benchmark for other efforts to understand vaccinations amount Saudi type 2 diabetics. Additionally, this study provides valuable evidence about demographic factors that may be used to identify individuals who are more likely to not have been vaccinated and the factors that may be influencing their decision not to be vaccinated.

At the same time, this study has some limitations. First, all of the data was coming from self-reports. Especially for reports about vaccination status, participants may inaccurately report their actual vaccination status. Some participants may simply be unable to recall when they were vaccinated or some may intentionally misreport. If the rate of over or underreporting was different for any of the sub-groups that we compared, this could result in over or underestimation of the prevalence rate ratios and, therefore, incorrect inferences about how these factors are impacting vaccination. Additionally, all of the findings in this study were cross-sectional.

Therefore, we cannot be sure about the causal direction between certain factors and vaccination. For example, believing that vaccination is important may not increase the probability of being vaccinated. Instead, it may be the case that following vaccination, individuals may be more likely to believe that vaccination is important. Finally, these findings may not be representative for the entire type 2 diabetic Saudi population. Because the data was collected from one hospital in one city, the characteristics of the patients attending this hospital may be different from the overall Saudi type 2 diabetic population and, therefore, impact how generalizable these findings are.

Recommendation

These findings suggest that efforts should be made to increase the uptake of both the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines among those with type 2 diabetes in Saudi Arabia. In particular, with respect to the pneumococcal vaccine, our findings suggest that there is extremely low awareness of the vaccine and information about the vaccine, which may be contributing to its low uptake. These findings suggest different methods for intervention to improve the prevalence of influenza vaccination. With respect to the demographic findings, particular efforts should be put into increasing influenza vaccination among older individuals, those with less than a college education, those who are not married, and those with certain chronic conditions. Effort should also be put into improving knowledge about the influenza vaccine, with particular attention paid to addressing the importance of vaccination for those with diabetes, the fact that the vaccine is effective at preventing influenza, and the low risk of side effects associated with the vaccine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our colleagues in Family medicine training program of Security forces hospital for their assistance in our study.

References

- 1.Naeem Z. Burden of diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci. 2015;9:5–6. doi: 10.12816/0024690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguiree F, Brown A, Cho NH, Dahlquist G, Dodd S, Dunning T, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Sixth Edition. 6th ed. Basel, Switzerland: International Diabetes Federation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Rubeaan K, Almashouq MK, Youssef AM, Al-Qumaidi H, Al DM, Ouizi S, et al. All-cause mortality among diabetic foot patients and related risk factors in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornum JB, Thomsen RW, Riis A, Lervang HH, Schønheyder HC, Sørensen HT. Type 2 diabetes and pneumonia outcomes: A population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2251–7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alotair HA, Elhoseny MA, Alzeer AH, Khan MF, Hussein MA. Severe pneumonia requiring ICU admission: Revisited. J Taibah Uni Medl Sci. 2015;10:293–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Rankings: Live Longer Live Better. Unites States: 2014. World Life Expectancy [Internet] Available from: http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/cause-of-death/influenza-pneumonia/by-country/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Bresee JS, Fry AM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices — United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66:1–20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6602a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster RG, Wright SM, Castrucci MR, Bean WJ, Kawaoka Y. Influenza--A model of an emerging virus disease. Intervirology. 1993;35:16–25. doi: 10.1159/000150292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, Almendares O, Moore MR, Whitney CG, et al. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:944–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6434a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeitouni MO, Al BAM, Al-Moamary MS, Alharbi NS, Idrees MM, Al SAA, et al. The Saudi Thoracic Society guidelines for influenza vaccinations. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:223–30. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.167065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alqahtani AS, Bondagji DM, Alshehari AA, Basyouni MH, Alhawassi TM, BinDhim NF, et al. Vaccinations against respiratory infections in Arabian Gulf countries: Barriers and motivators. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:212–21. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valdez R, Narayan KM, Geiss LS, Engelgau MM. Impact of diabetes mellitus on mortality associated with pneumonia and influenza among non-Hispanic black and white US adults. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1715–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wahid ST, Nag S, Bilous RW, Marshall SM, Robinson AC. Audit of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination uptake in diabetic patients attending secondary care in the Northern Region. Diabetic Med. 2001;18:599–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorska-Ciebiada M, Saryusz-Wolska M, Ciebiada M, Loba J. Pneumococcal and seasonal influenza vaccination among elderly patients with diabetes. Adv Hyg Exp Med (Online) 2015;69:1182–9. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1176772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotiropoulos A, Merkouris P, Gikas A, Skourtis S, Skliros E, Lanaras L, et al. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates among Greek diabetic patients in primary care. Diabet Med. 2005;22:110–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clancy U, Moran J, Tuthill A. Prevalence and predictors of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake in patients with diabetes. Ir Med J. 2012;105:298–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination coverage among persons aged>or=65 years and persons aged 18-64 years with diabetes or asthma--United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 53:1007–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson DR, Nichol KL, Lipczynski K. Barriers to adult immunization. Am J Med; 121;7(Suppl 2):S28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroneman M, van Essen GA, Paget WJ. Influenza vaccination coverage and reasons to refrain among high-risk persons in four European countries. Vaccine. 2006;24:622–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2018-19 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1–20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6703a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford ES, Mannino DM, Williams SG. Asthma and influenza vaccination: Findings from the 1999-2001 National Health Interview Surveys. Chest. 124:783–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahrabani S, Benzion U, Din GY. Factors affecting nurses’ decision to get the flu vaccine. Eur J Health Econ. 2009;10:227–31. doi: 10.1007/s10198-008-0124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumberg SJ, Vahratian A, Blumberg JH. Marriage, cohabitation, and men's use of preventive health care services. NCHS Data Brief. :1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:328–35. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]