Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this study is to explore the community's perceptions and knowledge of and attitudes toward Primary Healthcare Centers (PHCs) and Primary Healthcare Providers (PHPs) and the PHCs’ services in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, and to discover some of the reasons behind not attending the PHCs as the first choice to address a medical issue.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was done in Dammam and Al-Khobar cities, Saudi Arabia. 382 Saudi subjects were surveyed. Data was collected via a digital mobile-based survey and entered by the data collectors. SPSS version 25 was used to analyze the data.

Results:

Only 54% of the study population agreed to attend the PHCs as their first choice to address a medical issue. 72.3% of the respondents deemed the Emergency Department (ED) as a more important healthcare provider than a PHC.

Conclusion:

Acceptable perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes about PHCs and its services were noticed among the Saudi community in general. Public awareness campaigns are recommended to optimize full utilization of the PHCs’ services.

Keywords: Family medicine, family physicians, general practitioners, healthcare providers, primary, primary healthcare centers

Introduction

Family medicine is the medical specialty that can actually fulfill the goal of the primary healthcare system, which, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), is ‘better health for all’.[1] The American Academy of Family Physicians defines family medicine as ‘the medical specialty which provides continuing, comprehensive healthcare for the individual and family. It is a specialty in breadth that integrates the biological, clinical and behavioral sciences. The scope of family medicine encompasses all ages, both sexes, each organ system and every disease entity.’[2]

In February 1969, family medicine was first recognized as a primary medical specialty in America.[3] Primary healthcare centers (PHC) are the cornerstone of the healthcare system, as they were first introduced internationally in 1978, when the Declaration of Alma-Ata was issued by global healthcare leaders.

In most countries, primary healthcare physicians (PHP) compose the infrastructure for the healthcare system by serving as gatekeepers, connecting specialties, and offering continuous care for patients and their families. Research indicates that primary care is the most cost-effective.[4,5,6]

Today, America's Family Physicians (FPs) deliver the majority of healthcare to both rural and urban communities. Actually, Family Physicians are more widely spread throughout USA than practitioners of any other medical specialty.[7]

About 80% of Canadians have designated Family Physicians as their first healthcare providers to approach when declaring their medical problems.[8] More than 66% of them are convinced that family medicine is the most significant medical profession they seek.[9]

In 2004, a study was conducted in Pakistan documenting the perceptions of family medicine among patients visiting specialist physicians for treatment; more than half of the patients indicated that PHPs are fundamental to the healthcare system, and 80% of them believed that the healthcare system would not function well without specialist physicians.[10]

In 2009, a systematic review of the prevalence of inappropriate emergency services utilization by adults and accompanying factors was carried out. This study revealed a prevalence that varied from 20-40%, in which age and financial status were the main associates. It has been found that factors such as females with no primary diseases, patients with no regular follow-ups with a certain physician, and patients with no specific healthcare source are the ones that contribute the most to inappropriate utilization of the ED. Moreover, there were other difficulties concerning making appointments, longer waiting time, and short working hours at the PHC.[11]

As in other nations, here in Saudi Arabia, inappropriate utilization of the ED is a huge issue. Most of the patients in a military hospital ED presented with minor self-limiting complaints like respiratory tract infection, mild conjunctivitis, allergic rash, medication refill, minor burns, and gastrointestinal tract problems. The rush hour was mostly during the night.[12]

A study was conducted in Jeddah assessing emergency services utilization at three large governmental hospitals. The study indicated a significant proportion of non-urgent cases, with the following associated factors: young, non-married, and low-income. A very high proportion of patients visited the ED three to four times per year and not fewer than six times in a year for non-urgent cases. A large proportion of patients did not attempt to visit an outpatient clinic before presenting to the ED. Most patients attributed their attitude to the difficulty of setting appointments with a specialist due to overcrowding. Also, most patients have good knowledge about the services of PHCs. They however do not seek their help because of the negative perception they have of them. Inappropriate utilization of the ED led to congestion and increased waiting times of almost 3 hours.[13]

On the other hand, private specialist clinics also play a tremendous role in providing primary care here in Saudi Arabia, as they receive a significant proportion of patients. According to Al-Ghanim, the closeness of PHCs did not really matter to patients who preferred the private outpatient clinics, in comparison to those who attended public PHCs.[14] When Saeed explored the factors influencing the patients’ choice of healthcare provider, he found that patients preferred to have an experienced physician who was Arabic-speaking and Muslim as their primary care provider. The study showed that free services with a nearby PHC location were also an important factor.[15] This shows that there is a part of the population who would rather travel longer so as to satisfy their demands.[14]

In 2015, a study was conducted by Tariq Ali M Alzaied and Abdurrahman Alshammari in Riyadh for the evaluation of the current status of PHCs in the eyes of the Saudi community living there. More than 70% stated that their visits were good, but unfortunately, and as presumed, the majority of the population would not select a PHC as their first-line healthcare provider. Only 25.52% would select it as their first choice.[16] However, in 1993, Ali and Mahmoud found completely the opposite results, showing that 60% were satisfied with the services provided by the PHC, among whom 74.7% stated that it was their first choice. Those who were unsatisfied with the services also gave the same response.[17]

The 2 main reasons behind the poor utilization of the PHCs were: (a) lack of variety of specialties, and (b) doubting and mistrusting the physicians’ services. Another reason were medication prescription errors. Notably, a PHC's office hours and location did not make a difference to the population studied.[16]

Saudi Arabia is a developing country that makes significant efforts to promote health in its community. Also, it sets primary healthcare as one of its important areas to continuously develop.[18] Healthcare services in Saudi Arabia are provided via 3 providers: the Ministry of Health (MOH), other governmental healthcare providers, and the private sector.

The MOH is the main provider, with a significant number of healthcare institutions spread all over the country.[19] According to the Health Statistics Annual Book, in 2012, there were 2,259 PHCs throughout Saudi Arabia.[20] PHPs are either General Practitioners (GPs) or Family Physicians, with a total number of 243 and 334, respectively, in the Eastern Province.[21] In Saudi Arabia, GPs are those who hold a 7 year medicine and surgery bachelor degree. The Saudi Board of Family medicine was launched by the Saudi commission of Health Specialties in the year of 1995.

The objective of the current study is to determine the Saudi community's perceptions and knowledge of and attitudes toward PHCs as a first line healthcare provider in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This study is a quantitative cross-sectional survey that was conducted on the community of the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. The research was carried out between the months of November 2017 and May 2018. A convenient sample was used, and participants were all Saudis and at least 18 years of age.

In the months of February and March 2018, the Ministry of Health – General Directorate of Health Affairs ran 2 public health campaigns in 2 different shopping malls of the same region, Al-Rashed mall in Al-Khobar city, and Al-Othaim mall in Dammam city. The data was collected through these campaigns after getting permission from the head of the Directorate of Health Affairs.

The study questionnaire was a digital mobile-based survey and was filled by trained data collectors. It included an invitation letter that was introduced to the campaign's visitors. They were recruited and asked to read it prior to answering the questions. Another visit was to the employees of the Ministry of Health – Educational Supervision Office, who were also introduced to the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was generated after reviewing the articles of both Huda et al.[10] and Alzaied et al.[16] It was written in English first, then translated to Arabic through an accredited translation office (TransOrient). The Arabic version was then used to conduct this study, post which it was translated back into English. Both versions were validated by 3 family consultants.

After that, the questionnaire was piloted with the help of the head biostatistician in King Fahad Specialist Hospital-Dammam (KFSH-D). The questionnaire was given to 20 participants to assess their understanding, the questionnaire's feasibility, and the time needed for completion. Then, the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at KFSH-D.

The sample size was calculated using the RAOSOFT website; the margin of error is 5%, and the confidence interval is 95%. Considering a total population of 20,000+, an estimated sample size of 377 was needed.

The data were transferred to SPSS software version 25. In this study, the frequency tables are drawn in a manner that explores the findings as percentages and as measures of central tendencies and dispersion. Cross-tabulation ANOVA tables were made. The cut-off point of significance in all statistical tests is a P value of 0.05.

Results

This study was conducted with a total of 382 Saudi participants who lived in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. The participants were asked to share their impressions of previous visits to PHCs, compared to hospital doctors of other specialties. The study participants were 80.6% females and 19.3% males, with a mean age of 36 years. Almost 60% of the participants held a bachelor's degree, whereas 28% had a secondary school certificate, 6.8% had higher education, and 5.5% had other degrees. As for the respondents’ occupations, 23.3% worked in the education system, 22.3% were housewives, 12.6% were students, 11.5% worked in the private sector, and 7.3% were unemployed.

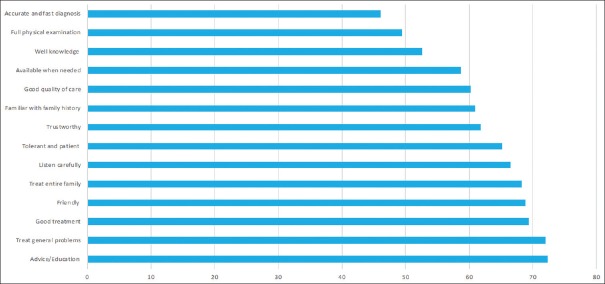

In the survey, the respondents were asked about the characteristics of the PHPs they had met before; most of the respondents agreed that PHPs were friendly, trustworthy, and knowledgeable. Also, the respondents agreed that PHPs listened carefully to their complaints, were more familiar with their family history, and were available when needed; they could treat general problems, were able to treat the whole family, and were tolerant and patient [see Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The Public's Perception about the characteristics of the PHPs

51% of the female respondents agreed that PHPs performed full physical examinations, unlike 43.2% of male participants, who disagreed. Only 49% of females and 33.8% of males agreed that PHPs could make accurate and fast diagnoses. According to 74.7% of the female respondents and 62% of males, PHPs provided advice and education. Only 62% of females and 52.7% of males agreed that PHPs provided an overall good quality of care.

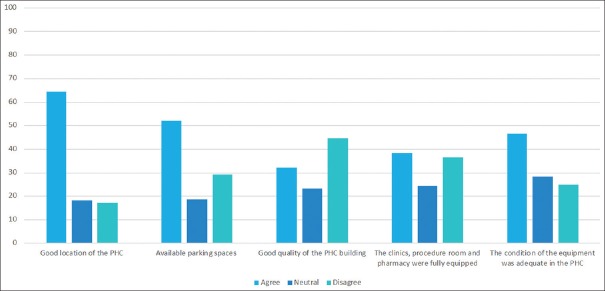

When asked about their impressions of previous visits to the PHCs, 2/3rd of the respondents agreed that the primary healthcare centers had good locations. Only 38.2% of the respondents agreed that the clinics’ procedure rooms and pharmacies were fully equipped, whereas 36.4% disagreed and 25.4% were neutral. It is also worth noting that 2/3rd of the respondents were not content with the condition of the equipment. Only 52% of the respondents thought that PHCs had available parking. As for the quality of the PHC buildings, almost 46% of females and almost 40% of males were not pleased [see Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The Public's Perception about the PHCs’ characteristics

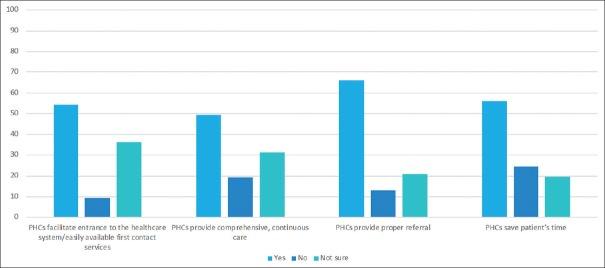

Respondents were then asked about their knowledge of the PHCs’ roles and the provided services in comparison to the ED and other specialist clinics. 54.5% of the respondents stated that the PHCs facilitated access to the healthcare system and indeed were easily available as first contact services, and 36.4% were not sure. Another 49.5% of the participants believed that the PHCs provided comprehensive, life long, continuous care. 66.2% of the participants trusted that the PHCs provided them with the proper referral to the needed specialty. Also, 56% of the participants assumed that the PHCs saved their time, while 24% of them did not. Almost 52% of the female respondents affirmed that PHCs provided lifelong care, unlike 60% of the males, who denied that [see Figure 3].

Figure 3.

The Public's knowledge about the PHC's roles and the services in comparison to the ED and other specialist clinics

To examine the respondents’ attitudes toward family medicine, they were asked about their preference of specialty (ED, PHC, or another specialist clinic) for the following scenarios or complaints: If they had painful urination, 50%, 30.9%, and 19.1% of the respondents would consult specialist clinics, the ED, and a PHC, respectively. 37.4% of the respondents would consider a PHC when having a severe headache, and 34.6% would consult a specialist clinic. 42.1% of the respondents would go to the ED for chest pain, whereas 35.6% would prefer specialist clinics. Meanwhile, only 22% of the respondents had the confidence to go to a PHC for chest pain. If they were having an asthma attack, 59.9% of the respondents stated that they would go to the ED, and 26% of them would attend a PHC. As for the antenatal clinic, postpartum follow-ups, and contraception counseling, 60.7% would go to specialist clinics, whereas 34.6% would consult a PHPs. In the case of fever, body ache, and cough, 64.1% would go to PHPs. For counseling on chronic diseases like HTN, 59.2% of the participants would prefer to go to PHPs, whereas 31.2% would go to specialist clinics. Moreover, the respondents fortunately chose to go to PHPs for scenarios such as a baby with diaper rash, vertigo, lightheadedness, and daily wound dressing. For a case like body rash with puffy lips and shortness of breath, 62.3% of the respondents stated that they would go to the ED, among whom 64% are females. If complaining about flank pain, 35.6% of the respondents would go to the ED, whereas 32.7% would visit a PHC, and 31.7% preferred specialist clinics.

When having a painful single-leg swelling, 41.1% of the respondents would go to the ED, 36.4% would prefer specialist clinics, and 22.5% would choose a PHC. Almost all the respondents luckily preferred going to the ED in scenarios such as RTA, full hand burn with blisters, a dog bite on the hand, and smoke inhalation after a house fire. 47.1% of the respondents would consult specialist clinics if having anxiety and lack of sleep, while 45% would go to a PHC in such case. In the scenario of having diarrhea and vomiting for 2 days, 43.2% of the participants would go to the ED, while 40% would prefer going to a PHC. If their two-week-old baby was jaundiced, 40% of the respondents would consult specialist clinics, whereas 31% would go to the ED, and 28.5% preferred a PHC [see Table 1].

Table 1.

Frequencies of the public’s attitude toward (ED, PHC, or specialist clinic)

| What is the preferred specialty department for the following scenarios/complaints | PHC | ED | Specialist clinics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Painful urination | 19.1% | 30.9% | 50% |

| Severe headache | 37.4% | 28% | 34.6% |

| Chest pain | 22.3% | 42.1% | 35.6% |

| Body rash with buffy lips and SOB | 15.2% | 62.3% | 22.5% |

| Flank pain | 32.7% | 35.6% | 31.7% |

| Asthma attack | 25% | 59.9% | 14.4% |

| Road traffic accident | 5.2% | 91.1% | 3.4% |

| ANC/contraception | 34.6% | 4.7% | 60.7% |

| Fever, body aches, sore throat and cough | 64.1% | 20.2% | 15.7% |

| Painful one leg swelling | 22.5% | 41.1% | 36.4% |

| Full Hand burn with blisters | 10.7% | 72.8 % | 16.5% |

| Counselling on chronic diseases (i.e. HTN) | 59.2% | 9.7% | 31.2% |

| Baby with diaper rash | 70.2% | 9.2% | 20.7% |

| Vertigo and lightheadedness | 56.5% | 24.1% | 19.4% |

| A dog bite on the hand | 12.6% | 79.6% | 7.9% |

| Anxiety and insomnia | 45% | 7.9% | 47.1% |

| Smoke inhalation after a house fire | 8.4% | 83.2% | 8.4% |

| Diarrhea and vomiting for 2 days | 36.9% | 43.2% | 19.9% |

| A two weeks old baby with jaundice | 28.5% | 31.2% | 40.3% |

| Daily wound dressing | 69.9% | 24.6% | 5.5% |

66.8% of the respondents preferred a PHC as their first choice to address a medical issue. However, the reasons that the other respondents would not go to a PHC as their first choice are as follows: 53 respondents out of 177 mentioned a long waiting time to see the physician, another 53 said the PHCs had unsuitable working hours, and 52 respondents believed that the physicians were untrustworthy. 11 of the respondents stated that it was because the PHCs were too far from their residences. Surprisingly, 72.3% stated that the ED is more important in general than PHCs.

Discussion

This study was conducted to study the reasons behind unnecessary visits to the ED or other private specialist clinics and hospitals.

One of the survey scenarios was about the participants’ first choice when having chest pain, in which 42.1% of the respondents stated that they would visit the ED, 35.6% of the respondents preferred to visit the specialist clinics, and the remaining participants would visit the PHC. Chest pain could have several benign, simple causes, all of which could be ruled out at a PHC. Unfortunately, there were also other health condition scenarios where the ED was the respondents’ first choice, even though it could be perfectly handled at a PHC, such as a case of an asthma exacerbation and gastroenteritis for 2 days.

A very high percentage of the study population believed the ED has a more important role in the healthcare system than the family medicine department.

Thus, it is necessary to improve the population's attitude toward the utilization of the ED versus the PHCs and to raise the awareness of the consequences of attending the ED for non-urgent complaints.[11] A notable proportion of the population actually thought that the ED was the first place to attend to address their problems.[13]

On the other hand, there are scenarios where the ED is chosen correctly, like having an RTA, a dog bite, a hypersensitivity skin reaction with shortness of breath and angioedema, a painfully swollen single leg, and inhaling smoke after a house fire. This denotes that obvious emergency conditions are clear enough to most of the study population.

A very important finding is that when the study population was asked about making the PHC their first choice to address a medical issue, 53.7% of the population answered ‘yes’, while 33.2% of the study population replied ‘no’. However, the remaining 13.1% replied with ‘yes’ but still added reasons for being unsatisfied with the provided services. These numbers indicate that most of the population would choose the PHC but are however not satisfied with the services provided to them. These results are similar to those of Ali and Mahmoud from 1993[16] and different than those of Alzaied's study,[17] in which only 25.52% stated that the PHC would be their first choice.

The participants’ reasons for not choosing the PHC as their first choice in this study are stated from the highest frequency to the lowest as follows: there is a long waiting time to see the physician, the physicians are untrustworthy, working hours are unsuitable, and the PHC is far from their residences. Then, the respondents provided other open individual reasons, some of which are misconceptions, such as that an appointment must be taken in advance. Other open individual reasons are as follows: poor medical equipment and building condition; lack of pharmacy supplies; having to pay for transportation; unavailability of laboratories, making results take a long time; no given advice or education on prevention, which is always better than cure; and issues like the PHC's staff being slow, disorganized, and sometimes lacking professionalism. All the previous reasons of the respondents are interestingly nearly compatible and sensible compared to the other results of this study [see Table 2]:

Table 2.

Reasons behind not attending the PHCs as a first healthcare provider

| Reasons | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Working hours are unsuitable. | 53 | 30 |

| It has a longer waiting time. | 53 | 30 |

| The physicians are untrustworthy. | 52 | 29 |

| Far from the house | 11 | 6.2 |

| Too much chatting and side talk between staff | 1 | 0.6 |

| An appointment must be made in advance. | 1 | 0.6 |

| No advice was given, though prevention is better than cure. | 1 | 0.6 |

| Poor patient management and lack of drug supplies and poor building | 1 | 0.6 |

| Lack of other medical specialties | 1 | 0.6 |

| Unavailable labs and proper medical equipment and common drugs | 1 | 0.6 |

| Poor building and equipment condition | 1 | 0.6 |

| Not providing money for transportation | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 177 | 100.0 |

65% of the respondents stated that the PHCs had good locations, as in the Alzaied's study that was conducted in Riyadh.[16] However, a significant proportion of the study population agreed that the facilities did not have enough parking spaces. They also agreed that the PHCs’ buildings are of extremely poor quality, and that their clinics, procedure rooms, and pharmacies are not fully equipped. The condition of the equipment was not adequate. These are facts that emphasize the importance and need of improving the centers to suit our country's new vision and mission.

Almost 70% of the community have deemed PHPs as friendly, able to treat general problems, able to treat the entire family, and able to provide advice and good treatment.

This explains the participants’ preference of the PHCs’ services for the following scenarios: common cold or flu, follow-up on chronic diseases like HTN, diaper rash, vertigo and lightheadedness, and daily wound dressing. However, slightly more than half of the study population stated that PHPs are knowledgeable, careful listeners, tolerant and patient, more familiar with family history, and trustworthy. This would indicate that a significant proportion of the respondents were not satisfied with PHPs care, which caused most of the respondents to choose to go to the specialist clinics instead of the PHC for the following simple conditions: painful urination, antenatal clinic and women's health issues like contraception, anxiety, and lack of sleep. In other examples, such as severe headache and flank pain, participants’ views were divided almost equally among ED, PHC, and specialist clinics. Some of the respondents mentioned after filling out the survey that they had guessed most of their answers, as they did not firmly know where to address certain medical issues. This clearly indicates their poor knowledge on the PHC's role in the healthcare system and the resources available. Therefore, it consequently shows a healthcare system delivery failure, as all of the previous medical complaints could be perfectly handled by PHPs. This shows that a significant proportion of the study population had higher esteem for the services of the specialist clinics than for those of the PHCs.

Approximately 60% of the respondents agreed that PHPs provided quality care in general, whereas the rest of the participants were either neutral or unsatisfied with the quality. This suggests that a significant proportion of the study population do not feel fulfilled at the end of the visit. Moreover, this is related to the fact that more than half of the study population did not agree that PHPs perform full physical examinations, can make accurate and fast diagnoses, and are unavailable when needed. Another plausible reason could be the fact that 40% of PHCs have no laboratories, and 65% have no x-ray services. This also might be because some of the physicians working in PHCs in SA lack expertise and qualification, as PHPs only constitute 10% of the total count of PHCs’ physicians.[22] This is due to the doctor/patient ratio, which is still low, as issued from the statistical report of the Ministry of Health.[23]

Only 54.5% of the respondents confirmed that the PHC provided them with an easy access to the healthcare system through first-contact services, and 56% of the participants stated that attending PHCs saved their time in comparison to the ED and specialist clinics, which implies that a significant proportion of the population may not be utilizing the PHCs properly and are not benefitting from the services. It can be inferred that this is why only 13.1% of the study population (55 respondents) stated that their reason for not going to PHCs is the long waiting time. Also, 66% of the respondents indicated that their PHC visits ended up with proper referrals. However, since this is from the respondents’ perspective, it is not clear whether they were really proper referrals or not. Merely 49.5% of the respondents agreed that PHC visits provided comprehensive, continuous care. The other half of the population either were hesitant or disagreed. This suggests that physicians are not emphasizing the importance of following up on medical issues or are not conducting enough age-appropriate screenings and medical counseling.

Conclusion

It was observed that around 1/3rd of the population replied that they would not visit the PHC as their first choice for several reasons. Also, most of the population was generally dissatisfied with the services they were offered there.

Unfortunately, most of the population chose the ED over the PHC as more important and essential in healthcare system delivery. There were several misconceptions about when to visit the ED and the private specialist clinics versus the PHC. Only 60% of the population agreed that the PHCs generally provided good-quality care in general.

Ultimately, this clearly enlightens us about the importance of raising awareness and giving recommendations for stakeholders and decision makers to:

The PHCs buildings and infrastructure need to be improved to fulfill its services and work flow. It has to be unified all over the country to serve its best utilization. The PHC building and landscape design have to be well studied to suit the requirements needed for attracting patients to revisit the facility. This also will create a better work environment which will improve staff productivity for the long run

An adequate expanding of staffing is very important to attain an acceptable amount of patients with minimum waiting hours and to provide proper and deserved session time for each patient; This will optimally avoid crowdedness. Proper staffing also maintains staff well-being. An accessible, coordinated and comprehensive care must be offered, in order to deliver a patient centered medical care. This can be achieved through the presence of a complete primary healthcare team

Resources and medical equipment must be provided on a monthly basis for each facility

Motivating the PHCs’ staff through conferences and workshops that spreads the significance of updating their knowledge, improving their communication skills, working in harmony, elevating their time management skills, and elevating the overall quality assurance by the use of customer feedback surveys

Promoting educational awareness campaigns and targeting the community in order to utilize family practice to its optimal potential. This can be achieved through programs that raise awareness of family medicine and highlight the significance of exploring its various aspects, as family medicine provides a wide range of health services for the whole community. This will ensure a cost-effective healthcare system that meets the expectations of our 2030 vision here in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, it is recommended that more future studies be done to improve and measure the success and progress of the PHCs’ services.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Health topics: Primary healthcare. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/primary_health_care/en/

- 2.American Academy of Family Physicians: About: Definition of family medicine. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/family-medicine-definition.html .

- 3.American Academy of Family Medicine: History of the Specialty. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.theabfm.org/about/history.aspx .

- 4.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:w184–97. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Care Now More Than Ever. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Family Physicians: About: Family medicine specialty. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.aafp.org/about/the-aafp/family-medicine-specialty.html .

- 8.Statistics Canada. Access to Health Care Services Survey. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decima public poll (CFPC, Oct 2003) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huda SA, Samani ZAA, Qidwai W. Perception about PHPs: Results of a survey of patients visiting specialist clinics for treatment. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:589–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carret MLV, Fassa AG, Domingues MR. Inappropriate use of emergency services: A systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:7–28. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui S, Ogbeide DO. Utilization of emergency services in a community hospital. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawoud SO, Ahmad AMK, Alsharqi OZ, Al-Raddadi RM. Utilization of the emergency department and predicting factors associated with its use at the Saudi Ministry of Health general hospitals. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8:90–106. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Ghanim SA. Factors influencing the utilisation of public and private primary health care services in Riyadh city. JKAU: Econ Adm. 2004;19:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeed AA, Mohamed BA. Patients’ perspective on factors affecting utilization of primary healthcare centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:1237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali M El-S, Mahmoud ME. A study of patient satisfaction with primary healthcare services in Saudi Arabia. J Community Health. 1993;18:49–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01321520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alzaied TAM, Alshammari A. An evaluation of primary healthcare centers (PHC) services: The views of users. Health Sci J. 2016;10:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Ahmadi H, Roland M. Quality of primary healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A comprehensive review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:331–46. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jannadi B, Alshammari H, Khan A, Hussain R. Current structure and future challenges for the healthcare system in Saudi Arabia. Asia Pacific J Health Manag. 2008;3:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Health. Statistical Report. Riyadh: 2006. p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Health. Statistical Year Book. Riyadh: 2015. p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Khaldi YM, Al-Ghamdi EA, Al-Mogbil TI, Al-Khashan HI. Family medicine practice in Saudi Arabia: The current situation and proposed strategic directions plan 2020. J Fam Community Med. 2017;24:156–63. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_41_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Health. Statistical Report. Riyadh: 2015. pp. 37–9. [Google Scholar]