Abstract

Axonal injury generates growth inert retraction bulbs with dynamic cytoskeletal properties that are severely compromised. Conversion of “frozen” retraction bulbs into actively progressing growth cones is a major aim in axon regeneration. Here we report that murine serum response factor (SRF), a gene regulator linked to the actin cytoskeleton, modulates growth cone actin dynamics during axon regeneration. In regeneration-competent facial motoneurons, Srf deletion inhibited axonal regeneration. In wild-type mice after nerve injury, SRF translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, suggesting a cytoplasmic SRF function in axonal regeneration. Indeed, adenoviral overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF (SRF-ΔNLS-GFP) stimulated axonal sprouting and facial nerve regeneration in vivo. In primary central and peripheral neurons, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP stimulated neurite outgrowth, branch formation, and growth cone morphology. Furthermore, we uncovered a link between SRF and the actin-severing factor cofilin during axonal regeneration in vivo. Facial nerve axotomy increased the total cofilin abundance and also nuclear localization of phosphorylated cofilin in a subpopulation of lesioned motoneurons. This cytoplasmic-to-nucleus translocation of P-cofilin upon axotomy was reduced in motoneurons expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP. Finally, we demonstrate that cytoplasmic SRF and cofilin formed a reciprocal regulatory unit. Overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF reduced cofilin phosphorylation and vice versa: overexpression of cofilin inhibited SRF phosphorylation. Therefore, a regulatory loop consisting of SRF and cofilin might take part in reactivating actin dynamics in growth-inert retraction bulbs and facilitating axon regeneration.

Introduction

Growth cone cytoskeletal dynamics are severely impaired in axonal injury, resulting in growth inert axon termini named retraction bulbs. Switching on actin growth cone dynamics in injured axon tips, thereby inducing de novo axon growth, is a current research effort in axon regeneration (Bradke et al., 2012). The transcription factor serum response factor (SRF) modulates physiological growth cone actin dynamics (Knöll and Nordheim, 2009). Upon Srf deletion, axon growth, branch formation, growth cone shape, and axon guidance are compromised in peripheral and central neurons (Alberti et al., 2005; Knöll et al., 2006; Wickramasinghe et al., 2008; Knöll and Nordheim, 2009; Stritt and Knöll, 2010; Lu and Ramanan, 2011; Meier et al., 2011). Growth cones derived from SRF-deficient neurons lack filopodia (Knöll et al., 2006; Stern et al., 2009; Meier et al.), thus resembling “frozen” retraction bulbs of transected CNS axons (Ertürk et al., 2007).

SRF exerts neuronal functions through interaction with the F-actin-severing factor cofilin. In SRF-deficient neurons, phosphorylated (i.e., inactive) cofilin is upregulated, suggesting that in wild-type cells, SRF is involved in cofilin activation (Alberti et al., 2005; Beck et al., 2012). SRF adjusts cofilin activity and responds to changes in the actin equilibrium by interacting with the cofactors myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTFs; Mokalled et al., 2010; Olson and Nordheim, 2010). Polymerization of G-actin to F-actin activates the MRTF-SRF circuit and enhances mRNA abundance of actin isoforms (Acta, Actc) and actin-binding proteins (e.g., actinin and calponin). SRF activity is regulated in part via phosphorylation at serine 103. In neurons, SRF phosphorylation and DNA binding is enhanced through cocaine administration (Vialou et al., 2012). Given its gene regulatory function, SRF localization was mainly considered to be nucleus restricted with a few exceptions (Stringer et al., 2002). This suggested the existence of thus far unidentified extranuclear SRF functions, which we addressed in this study.

Given its impact on neuronal motility, we investigated SRF's role during regrowth of injured axons. We used facial nerve axotomy (Fig. 1A), a well established model system of PNS axon regeneration (Moran and Graeber, 2004). In mice, facial motoneurons are localized in either of two brainstem nuclei. These motoneurons give rise to axons controlling, for example, whisker and eyelid muscle movement (Moran and Graeber, 2004; Raivich et al., 2004; Raivich, 2008). Neurons of transected PNS axons have a higher regeneration potential than CNS axons. This difference is in part due to the potential of PNS neurons to initiate robust axonal sprout formation. In axon sprouting, growth inert retraction bulbs are converted into dynamic, growth-competent growth cones. During facial nerve regeneration, extensive production of galanin-positive sprouts was reported after nerve injury (Makwana et al., 2010). Such molecules reactivating growth cone dynamics and axonal sprouting identified in PNS model systems as envisaged in this study might likewise stimulate CNS axon sprouting.

Figure 1.

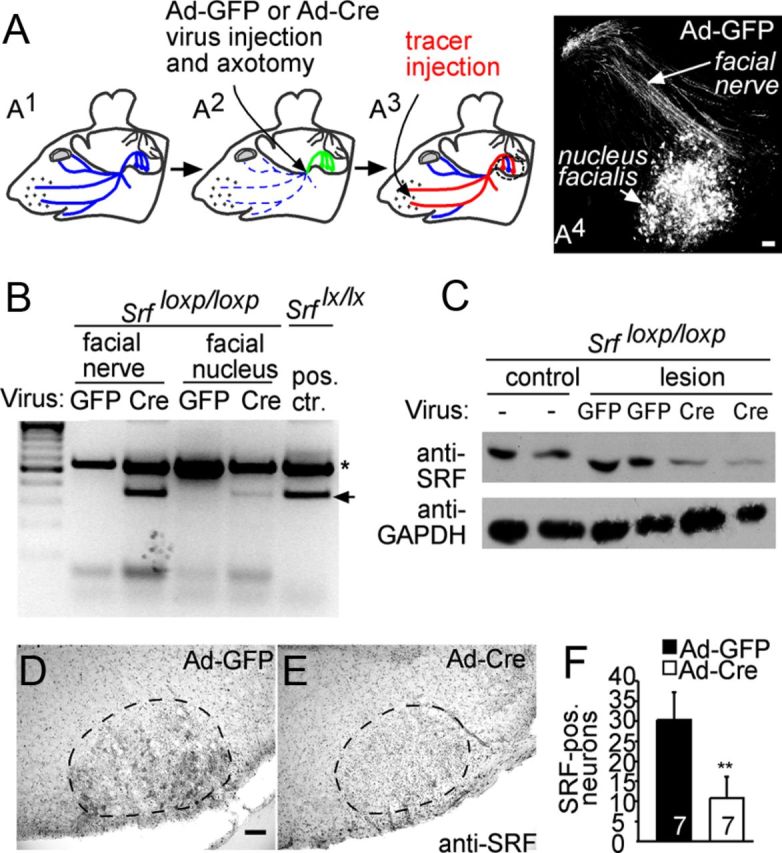

Virally delivered Cre recombinase depletes SRF in the facial nerve lesion model. A, A1, Scheme of the facial nerve outlined in blue. A2, Position of virus injection and axotomy is depicted by an arrow. Viral particles are retrogradely transported (green). A3, Tracer (red) is injected in the whisker pad and retrogradely transported to the cell bodies if nerve trajectories have regenerated or formed sprouts. A4, Efficiency of virus transduction in the nucleus facialis and facial nerve of an Ad-GFP-infected animal visualized with an anti-GFP antibody. B, Viral particles expressing either GFP (Ad-GFP) or Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre) were injected into the facial nerve of mice carrying two loxP-flanked Srf alleles. Two days later, genomic DNA of the facial nerve and facial nucleus was subjected to PCR. The recombined Srf locus is indicated by the arrow. The asterisk indicates un-recombined loci. Ad-Cre virus, but not Ad-GFP infection, resulted in Srf recombination in the facial nerve that was weaker in the facial nucleus. The positive control depicts Srf recombination driven by a Camk2α-iCre mouse strain. C, Western blot using an anti-SRF antiserum and lysates of facial nerves infected with the indicated viral particles and harvested 7 d after infection. In both Cre-infected animals, SRF levels are reduced compared with GFP controls. D–F, Sections through the disconnected facial nucleus of SrfloxP/loxP animals infected with Ad-GFP (D) and Ad-Cre (E) and stained for SRF expression. Ad-Cre (E) results in strong downregulation of SRF-positive facial motoneurons compared with Ad-GFP (D). F, Quantification revealed a 3-fold reduction of SRF-positive neurons in Ad-Cre compared with Ad-GFP animals. Numbers (n) of animals are indicated in figure bars. Scale bars: D, E, 100 μm.

Materials and Methods

Facial nerve transection.

Facial nerve transection was performed as described previously (Raivich et al., 2004). Adult mice of either sex (>2 months of age) were anesthetized, a skin incision was made behind the left ear, and the facial nerve was exposed. Then, 1 μl of Ad-vector (see below) was injected before lesion into the facial nerve using a Hamilton syringe (34 g). Afterward, the nerve was transected with microscissors ∼2 mm posterior to the foramen stylomastoideum and another 1 μl of Ad-vector was injected into the proximal nerve stump. Absence of eye lid closure and whisker movement proved successful nerve transection. Regeneration of the facial nerve was quantified by retrograde axonal tracing with Choleratoxin B-conjugated Alexa Fluor 555 (Ctx-Alexa 555; Invitrogen) or Fluorogold (FG; fluorochrome). For this, 4 × 1 μl of Ctx-Alexa 555 (0.03% in PBS) or FG (4% in H2O) was injected with a Hamilton syringe at multiple positions in each whisker pad. After 4 d, brains were dissected. Ctx- or FG-positive neurons of all sections of both facial nuclei per each animal were evaluated before immunohistological staining. All experiments are in accordance with institutional regulations by the local animal ethical committee (Regierungspräsidium Tübingen).

Histology.

Brains or facial nerves were fixed in 4% PFA or FA followed by preparation of 60 μm Vibratome or 5 μm paraffin microtome slices. Immunohistochemistry was performed using Biotin (1:500; Vector Laboratories)- or Alexa Fluor (1:500; Invitrogen)-conjugated secondary antibodies and peroxidase-based detection systems using the ABC complex (Vector Laboratories) and DAB as substrate. Primary antibodies included anti-SRF (rabbit, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-P-SRF (serine 103, rabbit, 1:500; Bioss), anti-MRTF-A (rabbit, 1:500; a kind gift from R. Treisman, Cancer Research Institute, London), anti-GFP (rabbit, 1:2500, Invitrogen), anti-P-cofilin (rabbit, 1:500, catalog #sc-21867; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-galanin (rabbit; 1:1500, Bachem), anti-cofilin (rabbit; 1:500, catalog #5175; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-FG (rabbit, 1:5000, catalog #AB153; Millipore).

Cell biology.

Primary postnatal day 1 (P1) mouse hippocampal, embryonic day 17.5 (E17.5) cortical, P3–5 mouse cerebellar, E16.5 rat, or adult mouse dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons of wild-type or SRF-deficient mice (Wiebel et al., 2002; Alberti et al., 2005) were prepared as described previously (Knöll et al., 2006). Neurons were electroporated with 3 μg of the plasmids using Mirus mouse neuron nucleofector solution. Cofilin-S3E-GFP was a kind gift from Kevin Flynn (DZNE, Bonn, Germany). Alternatively, neurons were infected with viral particles 3 h after plating at a final concentration of 107 particles/μl. After 24–48 h in the incubator, immunocytochemistry was performed.

Neurons were stained with antibodies recognizing βIII tubulin (mouse, 1:1000; Covance) and anti-GFP (rabbit, 1:2500; Invitrogen) using Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1500; Invitrogen). F-actin was labeled with Texas Red phalloidin (1:100; Molecular Probes).

Molecular biology.

SRF-GFP and SRF-ΔNLS-GFP expression vectors were kindly provided by J. Solway (Camoretti-Mercado et al., 2000). Cofilin constructs were used as described previously (Beck et al., 2012). The following Ad-vectors were used: Ad-Cre (1.5 × 1010 PFU/ml, catalog #1045; Vector Laboratories) and Ad-GFP (1 × 1010 PFU/ml, catalog #1060; Vector Laboratories), propagated, and CsCl purified. Production of an Ad-SRF-ΔNLS expressing Ad-vector was based on the SRF-ΔNLS-GFP plasmid received from J. Solway. The resulting ΔE1 Ad vector was amplified, purified by step and continuous CsCl gradients, and particle titers (1012/ml) and infectious titers (7.410/ml) were determined. A ΔE1 Ad vector only expressing EGFP from the hCMV promoter served as a control.

qPCR.

Facial nuclei were dissected from 300 μm brainstem sections prepared with a tissue chopper using tungsten needles. Facial nuclei of 4 mice for each condition were pooled and resulted on average in 0.5–0.75 μg of RNA. Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed with 0.5–0.75 μg of RNA using reverse transcriptase (Promega) and random hexamers. qPCR was performed on ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector with the Power PCR SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Expression was determined in relation to Gapdh RNA levels. Primer sequences will be provided upon request.

Biochemistry.

Cerebellar neurons plated in 10 cm dishes were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP 3 h after plating at a final concentration of 107 particles/μl. Alternatively, HEK293 cells plated in 10 cm dishes were transfected with constructs indicated using lipofectamine (Life Technologies). Twenty-four hours later, protein lysates were prepared as described previously (Stern et al., 2009).

Actin fractionation was performed essentially as described previously (Posern et al., 2002). Medium was removed and cells were collected in 1.5 ml of actin lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and complete protease inhibitors from Roche); 0.5 ml samples of medium were removed for input samples. Remaining lysates were centrifuged for 2 h at 4 degrees at 100,000 × g. Supernatants were transferred to a new tube (the G-actin fraction). The pellet (the F-actin fraction) was resuspended in 1 ml of actin lysis buffer and sonified (Branson sonifier; 5 × 10 s, duty cycle constant, output control 3). Samples were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE. Western blotting involved the following antibodies: mouse anti-GFP (1:1000; see above), rabbit anti-MRTF-A (1:500; a kind gift from R. Treisman, London), mouse anti-actin (1:1000, catalog # LCK9001; Linaris), rabbit anti-cofilin, rabbit anti P-cofilin, and rabbit anti P-SRF Ser-103 (all at 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology).

Statistical analysis.

Numbers (n) of independent cell cultures or animals are indicated in figure bars or text. For cell culture experiments, at least three independent experiments were performed and at least 30 neurons were analyzed in each experiment. Statistical significance was calculated using two tailed t tests with *, **, and *** indicating p ≤ 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively. SD is provided if not mentioned otherwise.

Results

SRF deletion reduces facial nerve regeneration in vivo

Reactivation of neuronal motility is a central aim in improving axon regeneration. Therefore, we investigated whether SRF's well documented impact on neurite and growth cone motility contributes to axon regeneration in vivo.

To address a potential role of SRF in axon regeneration, we performed SRF loss-of-function experiments after facial nerve transection (Figs. 1, 2). SRF depletion from facial motoneurons was achieved with adenoviral-mediated delivery of Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre) into mice harboring loxP flanked Srf alleles (Wiebel et al., 2002; Alberti et al., 2005). Virally delivered Ad-Cre resulted in recombination of the Srf (flex1-neo) allele (Fig. 1B) and reduction of SRF protein levels in the facial nerve and nucleus (Fig. 1C–F). As a control, adenoviruses expressing GFP (Ad-GFP) were used (Fig. 1B–F). The facial nerve was unilaterally lesioned, followed by virus injection into the lesioned nerve stump (Fig. 1A2). The unlesioned contralateral facial nerve served as control and was not infected because virus injection per se induces a lesion. Ad-Cre and Ad-GFP viral particles infected facial nerve axons (Fig. 1A4) and surrounding cells such as Schwann and supporting cells (data not shown). Importantly, viral particles were retrogradely transported along the facial nerve to the facial nucleus, resulting in transduction of 40–70% of all motoneurons (Fig. 1A4). Viral protein expression commenced 1 d after transduction and persisted for up to 30 d (data not shown).

Figure 2.

SRF depletion reduces facial nerve regeneration. A–D, The facial nerve of Srfflex1/flex1 animals was unilaterally lesioned. Seventeen days after axotomy, a fluorescently labeled tracer (Ctx Alexa 555) was injected and allowed to retrogradely label facial motoneurons for 4 d. After a total of 21 d, tracer-positive facial motoneurons were quantified in unlesioned (A, B) and lesioned (C, D) facial nuclei. On the unlesioned side, numbers of facial motoneurons in Ad-GFP- (A) and Ad-Cre (B)-injected animals were similar. On the lesioned side of control animals injected with Ad-GFP, robust axon regeneration was observed (C). In contrast, SRF ablation upon Ad-Cre injection decreased numbers of Ctx-positive neurons on the lesioned side (D). E, F, Galanin was found on the lesioned side of Ad-GFP (E), but only sparsely in Ad-Cre (F)-infected animals. G, Quantification of average Ctx-positive neuron number/section for the unlesioned and lesioned facial nucleus. The number of tracer-positive neurons on the lesioned side was ∼3-fold reduced upon Ad-Cre injection compared with Ad-GFP. H, The percentage of regenerating neurons is depicted by the ratio of neurons present on lesioned and control side. In Ad-GFP-injected animals, 50% of neurons regenerated. In contrast, only 15% of SRF-deleted neurons incorporated the tracer. Individual squares reflect independent animals analyzed. Facial nuclei are delineated by dashed lines. Scale bars in A–F, 100 μm.

To quantify the regeneration outcome, a fluorescent tracer was injected in both whisker pads 17 d after nerve injury (Fig. 1A3). Axons successfully reconnected to whisker muscles allow for retrograde tracer transport to the motoneuron cell bodies, which were then counted (Fig. 1A3). These tracer signals in the motoneuron cell bodies might reflect canonical axon regeneration (i.e., new axon extension occurring at the tip of a transected axon in the lesion site). In addition, the formation of new axon sprouts (i.e., branches originating at axon regions that are more remote from the injury site) may contribute to tracer incorporation in facial motoneuron cell bodies.

Having established SRF depletion with this experimental system (Fig. 1), we assessed numbers of tracer-positive facial motoneurons 21 d after injury (n = 8 animals each condition; Fig. 2). The total number of facial motoneurons present on the unlesioned control side of Ad-GFP- (Fig. 2A) or Ad-Cre (Fig. 2B)-infected animals was expectedly similar (quantified in Fig. 2G). For the quantification (Fig. 2G,H), all animals tested were depicted by individual squares to reflect the variation of regeneration outcome between different animals. Variations in the regeneration success in these in vivo surgery experiments were caused by susceptibility to anesthesia, removal of tissue surrounding the facial nerve, time of recovery after surgery, and freehand application of the retrograde tracer. Next, we quantified tracer-positive motoneurons in the axotomized facial nucleus of Ad-GFP- (Fig. 2C) and Ad-Cre (Fig. 2D)-infected animals. The number of motoneurons present on the uninjured side was set to 100%. In Ad-GFP injected control animals, 50% (± 10%) of motoneurons were tracer positive after axotomy (Fig. 2C; quantified in G,H). In contrast, upon SRF depletion in motoneurons, axon regeneration was reduced (Fig. 2D). Now, only ∼15% of all motoneurons regenerated (Fig. 2D; quantified in G,H). In addition to tracer incorporation, we quantified galanin expression, a marker of successful axonal sprout formation (Raivich et al., 2004). On the lesioned side of Ad-GFP injected animals, galanin-positive motoneurons and protrusions were observed (Fig. 2E). However, inspection of lesioned motoneurons of SRF-depleted facial nuclei revealed a reduction of galanin-positive axon sprout formation (Fig. 2F). This suggests that formation of axonal sprouts is impaired by SRF deficiency. In contrast to axonal sprouting (Fig. 2E,F), apoptosis and immune cell responses (T cells and microglia) were not altered upon SRF depletion (data not shown).

In sum, SRF ablation in facial motoneurons significantly impaired axonal regeneration.

Axon injury modulates SRF, P-SRF and MRTF-A expression and localization

To investigate mechanisms by which SRF modulates axon regeneration, we analyzed whether SRF, P-SRF and MRTF-A expressions were modulated by axon injury (Fig. 3). For this, SRF, P-SRF and MRTF-A expression was monitored in motoneurons 1, seven and twenty-one days post facial nerve lesion (; n ≥ 4 mice for each time-point; Fig. 3 and data not shown).

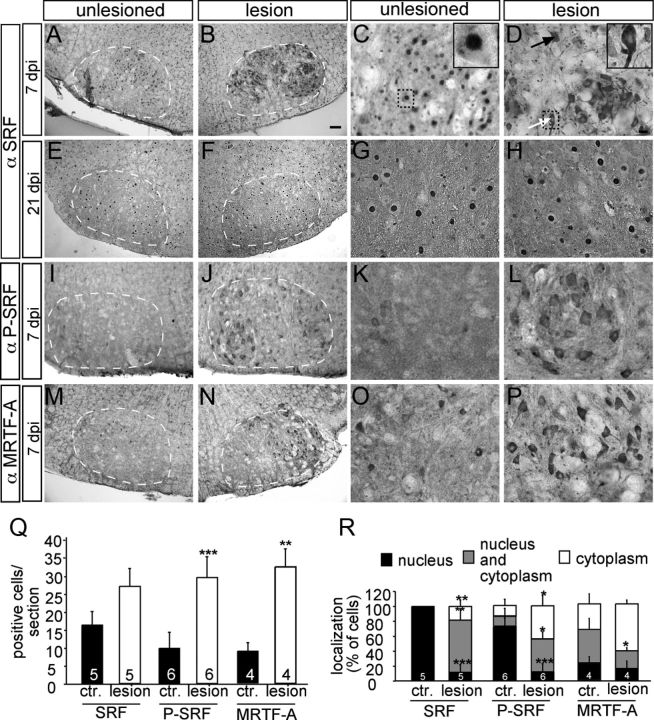

Figure 3.

Neuronal injury induces cytoplasmic SRF and P-SRF accumulation and MRTF-A upregulation. Seven (A–D and I–P) and 21 (E–H) days after lesion, control and lesioned facial nuclei were analyzed for SRF (A–H), P-SRF (I–L), or MRTF-A (M–P) expression. A–D, SRF was confined to nuclei of unlesioned motoneurons (A, C). In contrast, SRF was redistributed on the lesioned (B, D) facial nucleus compared with the control side at 7 d after facial nerve injury (A, C). Now, SRF localized to the cytoplasm of cell bodies and neurites (B and see arrows in D). Inserts in C and D are higher magnifications of individual motoneurons labeled by dotted areas. Black arrow depicts a neuron with nuclear and cytoplasmic staining; white arrow shows a neuron with cytoplasmic staining. E–H, At 21 d after injury, SRF was localized to the nucleus of motoneurons of both the control (E, G) and lesioned (F, H) side. I–L, P-SRF was upregulated in lesioned (J, L) compared with unlesioned (I, K) motoneurons. P-SRF was mainly found in the cytoplasm. M–P, Numbers of MRTF-A-positive cells were strongly increased upon facial nerve axotomy (N, P) compared with control (M, O). MRTF-A was confined to the cytoplasm on both sides. Q, Quantification of cells/section staining positive for SRF, P-SRF, or MRTF-A. R, Quantification of subcellular localization of SRF, P-SRF, or MRTF-A in percentage of cells, as indicated by the label. Scale bars: A, B, E, F, I, J, M, N, 100 μm; C, D, G, H, K, L, O, P, 20 μm.

In noninjured motoneurons, SRF was confined to the cell nucleus at all time-points (Fig. 3A,C,E,G; quantified in Fig. 3R). In contrast, when analyzing lesioned motoneurons, a nuclear-to-cytoplasmic SRF relocalization was observed (Fig. 3B,D,R). This cytoplasmic SRF localization commenced already 1 d after injury (data not shown). At 7 d post injury, SRF was present in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm in the majority (70 ± 10%) of cells (Fig. 3D, arrows; quantified in Fig. 3R). SRF even entered neurites of lesioned motoneurons pointing at a novel cytoplasmic SRF function (Fig. 3D). Therefore, in addition to nuclear SRF, a cytoplasmic resident SRF protein might be involved in axon regeneration (Fig. 4). This cytoplasmic SRF localization was reverted to a primarily nuclear position 21 d after axotomy (Fig. 3F,H). The number of SRF-positive motoneurons was slightly upregulated upon injury (Fig. 3Q). Our observation differs from another study where SRF relocalization was not observed using a different anti-SRF antiserum (Herdegen et al., 1997). We used a second SRF-specific antiserum to corroborate our findings (data not shown). Also, cytoplasmic transcription factor localization is not a general mechanism inflicted by motoneuron injury as c-Jun and ATF3 remained nuclear upon facial nerve injury (Raivich et al., 2004).

Figure 4.

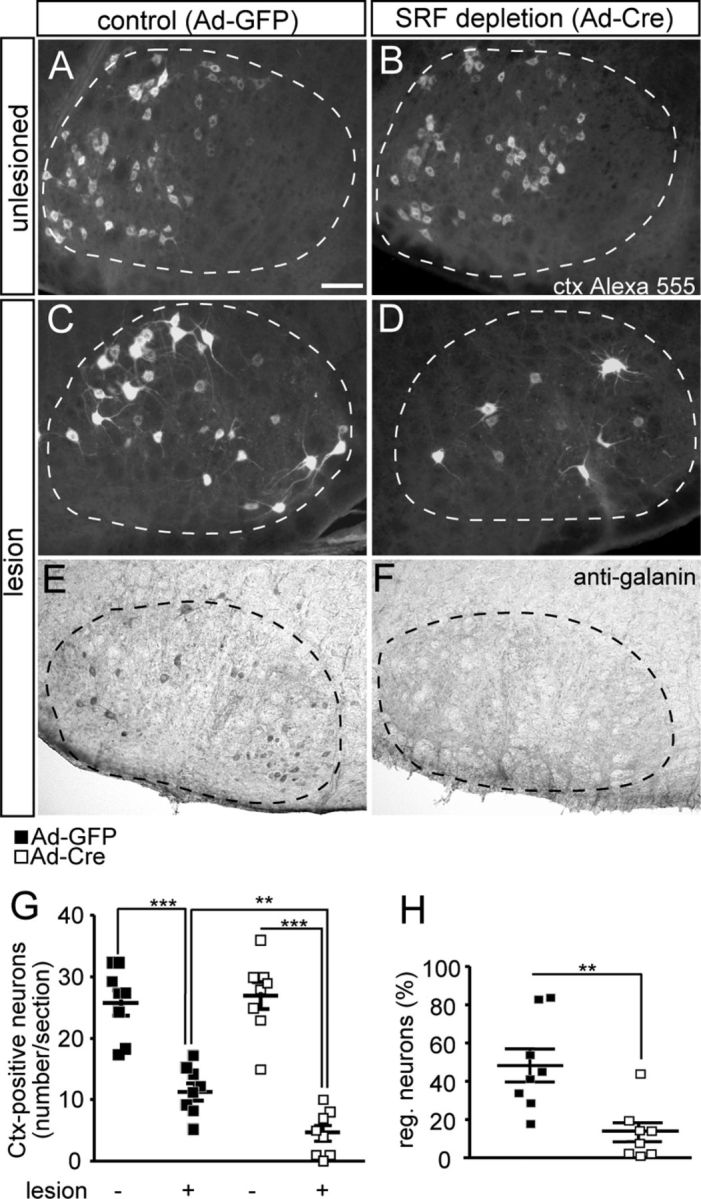

Cytoplasmic SRF facilitates facial nerve regeneration in vivo. A, A1, The facial nerve is outlined in blue. A2, Ad-GFP or Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP virus (green) was injected. The injection and axotomy position is depicted by an arrow. A3, Tracer (FG, red) is injected in the whisker pad and retrogradely transported to cell bodies of regeneration or sprout forming neurons. A4, Lesioned facial nucleus of an Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP-injected animal. Overexpression of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP resulted in cytoplasmic SRF localization. A5, Higher magnification of neuron labeled by asterisk in A4. B–E, Inspection of axon regeneration of GFP expressing neurons only. The number of FG-positive neurons on the unlesioned side was comparable between both virus types (B, D). In Ad-GFP-infected animals, ∼30% of all neurons expressing GFP were also tracer positive (labeled with an arrow in C). In contrast, >70% of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP-expressing motoneurons were positive for the regeneration, indicating tracer (labeled with arrows in E). F–I, Visualization of the total population of FG-positive motoneurons in control (F, H) or lesioned (G, I) facial nuclei of GFP- (F, G) or SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (H, I)-expressing animals. SRF-ΔNLS-GFP enhanced the number of tracer-positive neurons in lesioned facial nucleus (I) compared with GFP (G). J–M, Nissl staining labels all facial motoneurons. In Ad-GFP-infected animals, the number of motoneurons was decreased upon lesion (J, K). In contrast, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP prevented motoneuron loss upon facial nerve injury (L, M). N–Q, In Ad-GFP-expressing facial nuclei, galanin-positive neurons were downregulated upon lesion (N, O). In contrast, more galanin-positive neurons were present upon lesion in animals expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (P, Q). R, Quantification of axonal regeneration counting all FG tracer-positive cells (each square depicts one animal). The average number of FG-positive neurons/section upon lesion is increased by SRF-ΔNLS-GFP. S, Percentage of tracer-positive neurons in the total motoneuron population depicted by the ratio of neurons present on the control and lesioned side. T, U, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP increased the number of Nissl- (T) and galanin-positive (U) neurons upon facial nerve injury. Scale bars: A4, F–Q, 100 μm; B–E, 10 μm; A5, = 5 μm.

SRF phosphorylation is enhanced by neuronal activation (Vialou et al., 2012). Therefore, we inspected whether SRF phosphorylation is also induced during axonal injury (Fig. 3I–L). For this, we used a Phospho-SRF (P-SRF) specific antiserum recognizing serine 103 phosphorylated SRF. P-SRF was barely present in intact motoneurons (Fig. 3I,K). In contrast, P-SRF was upregulated in lesioned motoneurons (Fig. 3J,L,Q). Moreover, similar to total SRF (Fig. 3D), P-SRF was mainly confined to the cytoplasm and only weakly observed in the nucleus (Fig. 3L,R). Therefore, phosphorylated SRF was present in the cytoplasm of motoneurons during an early phase of axon regeneration in vivo.

In addition to SRF, we inspected the SRF cofactor MRTF-A (Fig. 3M–P). The number of cells expressing MRTF-A increased at 1 d (data not shown) and 7 d post injury (Fig. 3N,P; quantified in Fig. 3Q). MRTF-A localization was mainly restricted to the cytoplasm of control and lesioned neurons (Fig. 3P,R).

Together, we here report a nuclear-to-cytoplasmic redistribution of SRF induced by physical (i.e., nerve transection) cellular insult.

Cytoplasmic SRF enhances facial nerve regeneration

SRF accumulated in the cytoplasm upon axotomy of facial motoneurons (Fig. 3) suggesting SRF's potential to modulate facial nerve regeneration by a novel cytoplasmic function. To address this possibility in vivo, we overexpressed a cytoplasmically localized SRF mutant protein (SRF-ΔNLS-GFP) in facial motoneurons (Fig. 4). SRF-ΔNLS-GFP harbors mutations in the nuclear localization signal thereby localizing to the cytoplasm (Camoretti-Mercado et al., 2006). Overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF was accomplished by unilateral facial nerve infection of animals with adenoviral particles driving SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP) expression. Indeed, overexpression of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP resulted in cytoplasmic SRF localization in axotomized motoneurons (Fig. 4A4,A5) and thus appears suitable to address functional consequences of cytoplasmic SRF localization. As control, we unilaterally overexpressed GFP by Ad-GFP infection (n = 10 animals each virus; Fig. 4A). After 17 d of regeneration, a fluorescent tracer (Fluorogold, FG) was injected in both whisker pads followed by histological analysis 4 d later (Fig. 4A3). In these gain-of-function experiments, regeneration of transected facial motoneurons was quantified by focusing on GFP-positive neurons (Fig. 4B–E) or all motoneurons regardless of GFP expression (Fig. 4F–I,R,S).

First of all, regeneration was quantified by comparing GFP versus SRF-ΔNLS-GFP expressing neurons (Fig. 4B–E). The number of tracer-positive neurons on the noninfected and unlesioned control side was expectedly comparable between Ad-GFP (Fig. 4B,F) and Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 4D,H) animals (quantified in Fig. 4R,S). To quantify the regeneration on the lesioned facial nucleus, the ratio of GFP and FG tracer double-positive neurons in relation to the total number of GFP-positive neurons was quantified. Of the motoneurons expressing GFP only (Fig. 4C, arrow), ∼30% were double-positive indicating their successful regeneration (30 ± 16%). In contrast, >70% (71 ± 15%; p = 0.00031) of motoneurons expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP were also tracer-positive (Fig. 4E, arrows). Therefore, cytoplasmic SRF enhanced facial nerve regeneration more than twofold (Fig. 4R,S).

SRF affects neighboring cells via paracrine mechanisms (Stritt et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2010). Hence, we quantified the total number of tracer-positive motoneurons regardless of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP expression (Fig. 4F–I,R,S). The number of FG-positive motoneurons on the uninjured sides was comparable between both virus transductions (compare Fig. 4F,H; quantified in Fig. 4R). On the lesioned side of Ad-GFP expressing animals, ∼40% of all motoneurons regenerated (Fig. 4G,R,S). In contrast, transduction with Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in the number of all regenerating neurons (Fig. 4I,R,S). This suggests that SRF-ΔNLS-GFP enhanced the regeneration capacity of neighboring GFP-negative cells.

Upon facial nerve injury, neuron loss is well documented (Moran and Graeber, 2004). We also noted loss of Nissl-positive motoneurons at 21 d after lesion comparing uninjured (Fig. 4J) with lesioned (Fig. 4K; quantified in Fig. 4T) facial nuclei of Ad-GFP infected animals. This motoneuron loss was not as pronounced when inspecting animals injected with Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 4L,M,T).

Next we analyzed axonal sprouting, which was decreased in SRF depleted facial motoneurons (Fig. 2). In line with a putative sprout inducing potential of cytoplasmic SRF, we observed more galanin-positive axonal sprouts in Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 4Q) compared with Ad-GFP (Fig. 4O; quantified in Fig. 4U)-infected animals.

In addition, we investigated apoptosis, infiltration of the nucleus facialis by immune cells (microglia) and proliferation and did not observe major changes between Ad-GFP and Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP infected animals (data not shown).

In summary, our results reveal an increase of facial nerve regeneration upon expression of cytoplasmic SRF.

Mechanisms of cytoplasmic SRF function in primary neurons and in vivo

Data obtained so far revealed that SRF loss-of-function (Figs. 1, 2) impaired axon regeneration. Conversely, overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF enhanced facial nerve regeneration (Fig. 4), indicating the importance of SRF's cytoplasmic localization in the regeneration response. In a next step, molecular and cellular mechanisms stimulated by cytoplasmic SRF including gene transcription (Fig. 5) and neuronal motility (Fig. 6) were investigated.

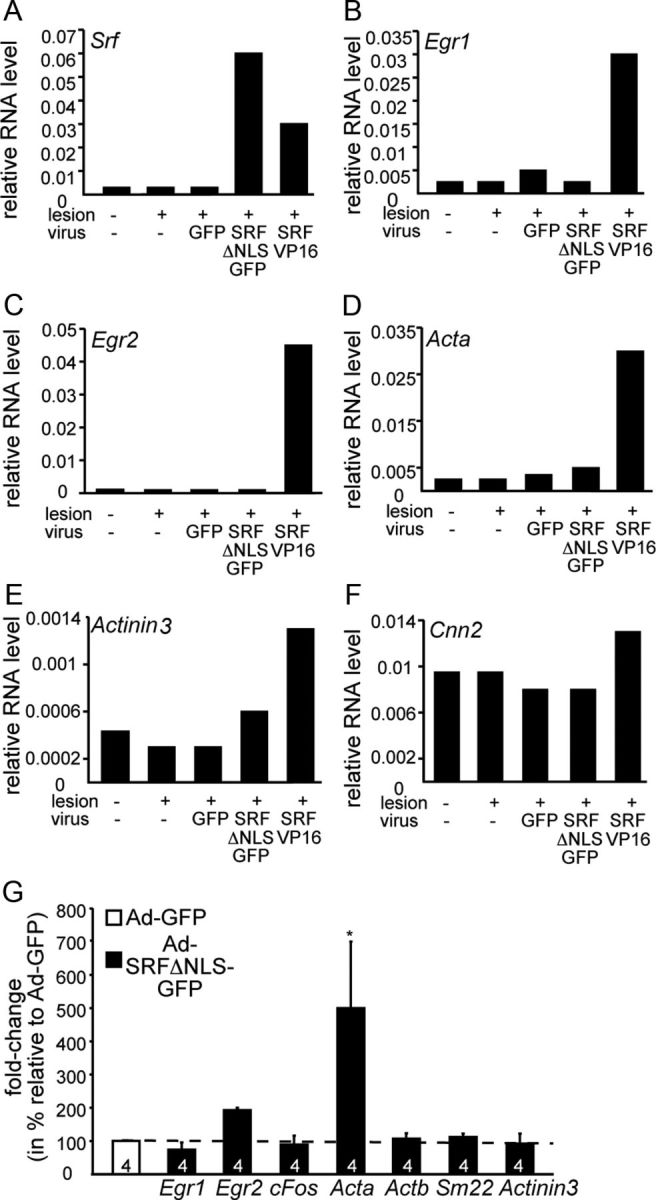

Figure 5.

Impact of cytoplasmic SRF on gene expression. A–F, Facial motoneurons were-infected with Ad-GFP, Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP, or Ad-SRF-VP16. Three days later, cDNA of the unlesioned and lesioned sides was subjected to qPCR; primer pairs are indicated. SRF-VP16 induced mRNA levels of Egr1 (B), Egr2 (C), Acta (D), Actinin 3 (E), and Cnn2 (F). In contrast, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP had almost no effect on mRNA abundance of genes depicted. G, Cortical neurons were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP. Three days later, mRNAs were isolated and cDNA was subjected to qPCR; primer pairs are indicated. SRF-ΔNLS-GFP only affected mRNA abundance of Egr2 and Acta and had almost no effect on mRNA abundance of all other genes depicted.

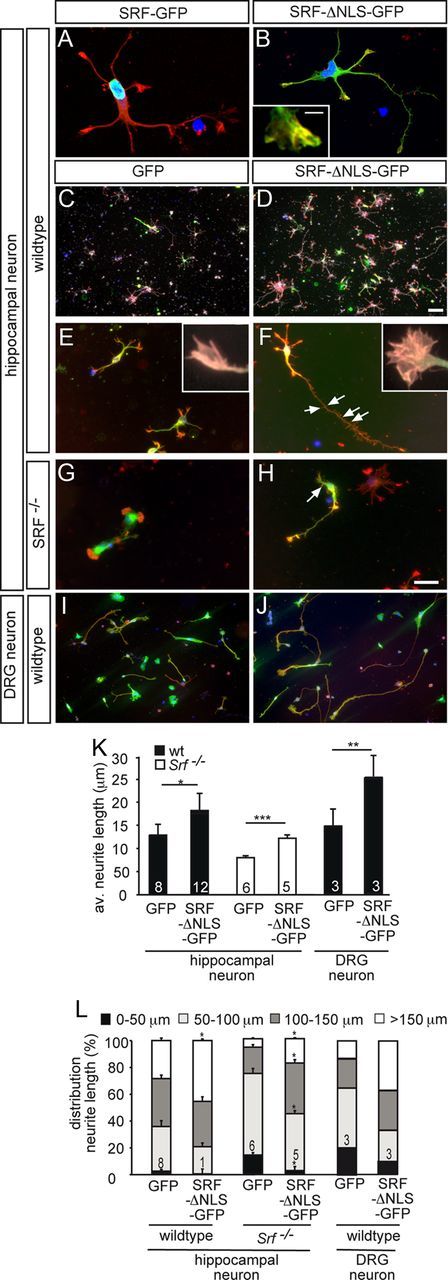

Figure 6.

Cytoplasmic SRF stimulates neuronal motility in vitro. Hippocampal (A–H) or DRG (I, J) neurons grown for 2 d in culture were stained for GFP (green), F-actin (red), βIII tubulin (white in C, D), and DAPI (blue). A, B, A fusion protein consisting of full-length SRF and GFP (SRF-GFP) localized to the nucleus (A). SRF-ΔNLS-GFP was mainly found in the cytoplasm and also entered neurites and growth cones (B). Cytoplasmic SRF colocalized with F-actin in growth cones (see insert in B). C, D, In wild-type neurons, overexpression of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (D), in contrast to GFP (C), resulted in increased numbers of βIII tubulin-positive neurons. E–H, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (F, H) enhanced growth cone area, filopodia number, neurite length, and overall F-actin content in wild-type (F) and SRF-deficient (H) neurons compared with GFP (E, G). Inserts in E and F show individual growth cones. Number of secondary branches (arrows in F, H) was also increased by SRF-ΔNLS-GFP. I, J, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (J) enhanced neurite length in DRG neurons compared with control (I). K, L, Quantification of the average neurite length (K) and distribution of neurite length ranging from 0 to >150 μm (L). Scale bars: A, B, E–J, 10 μm; C, D, 100 μm; inserts in B, E, F, 1 μm.

The cytoplasmic localization of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP suggests that this SRF protein modulates gene expression not directly and perhaps only via nuclear SRF interaction. To address this, we analyzed cytoplasmic SRF's impact on target gene expression in vivo (Fig. 5A–F) and in vitro (Fig. 5G).

In vivo, facial motoneurons were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 5A–F). Three days later, mRNA was subjected to qPCR analysis (n = 4 animals pooled). Data obtained were compared with animals infected with Ad-SRF-VP16, a potent inducer of SRF target genes including immediate early (IEG; c-Fos, Egr1, Egr2, Arc) and actin cytoskeleton related genes (Stritt et al., 2009). SRF-VP16 upregulated mRNA levels of the SRF target genes Egr1 (Fig. 5B), Egr2 (Fig. 5C), Acta (Fig. 5D), actinin (Actn3; Fig. 5E) and calponin (Cnn2; Fig. 5F). In contrast to SRF-VP16, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP achieved no or only mild induction of these SRF target genes (Fig. 5B–F).

Similarly, cytoplasmic SRF had only little impact on gene expression in primary cortical neurons (n = 4 cultures; Fig. 5G) with one exception. Acta was induced by SRF-ΔNLS-GFP in primary neurons (Fig. 5G), however not in motoneurons in vivo (Fig. 5D).

In summary, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP had negligible influence on SRF target gene expression.

Next, we turned toward potential functional consequences of cytoplasmic SRF expression on neuronal motility (Fig. 6). For this, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP overexpression in primary CNS (i.e., hippocampal; Fig. 6A–H) and peripheral (i.e., DRG; Fig. 6I,J) neurons was used.

Similar to previous in vivo experiments (Fig. 4), SRF-ΔNLS-GFP was predominantly localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 6B). Closer inspection revealed that SRF-ΔNLS-GFP localized to neurites and growth cones (Fig. 6B). In growth cones, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP partially colocalized with F-actin-positive filopodia (insert, Fig. 6B). In opposite to SRF-ΔNLS-GFP, wild-type SRF-GFP resided in the nucleus (Fig. 6A).

To start with, we investigated the impact of cytoplasmic SRF on overall abundance of βIII tubulin-positive neurons in this mixed primary culture system (n ≥ 5 cultures/condition; Fig. 6C,D). SRF-ΔNLS-GFP expression (Fig. 6D) doubled the abundance of βIII tubulin-positive neurons in culture compared with GFP alone (GFP: 17 ± 6 neurons/area; SRF-ΔNLS-GFP: 35 ± 7 neurons/area; p = 0.00035; Fig. 6C). This implies a-positive influence of cytoplasmic SRF on neuronal differentiation in general. Comparing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP expressing cultures (Fig. 6D) with GFP control cultures (Fig. 6C), we noted an increase in F-actin staining suggesting an impact of cytoplasmic SRF on F-actin rich growth cones. Indeed, quantification of individual growth cones revealed an increase of F-actin rich structures such as growth cone area (GFP: 26 ± 5 μm2; SRF-ΔNLS-GFP: 40 ± 7 μm2; p = 0.01) and filopodia number (GFP: 5.6 ± 0.9; SRF-ΔNLS-GFP: 8 ± 1.6; p = 0.017) in wild-type neurons expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 6E,F, inserts).

We further analyzed the influence of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP on neurite growth of wild-type neurons (Fig. 6E,F). SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 6F) increased primary neurite length in wild-type neurons by ∼30% compared with GFP expressing neurons (Fig. 6E; quantified in Fig. 6K,L). To exclude that cytoplasmic SRF stimulated neurite outgrowth by interacting with endogenous nuclear SRF, we used SRF-deficient neurons (Fig. 6G, H). Indeed, compared with GFP alone (Fig. 6G), SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 6H) increased neurite length in SRF-deficient neurons on average by 40% and doubled the percentage of neurons bearing longest neurites (i.e., > 100 and 150 μm; Fig. 6K,L). Therefore, similar to wild-type SRF-GFP (Beck et al., 2012), SRF-ΔNLS-GFP rescued neurite growth inhibition inflicted by SRF deficiency.

Further, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP enhanced secondary neurite branching in wild-type (GFP: 1.5 ± 0.3 branches; SRF-ΔNLS-GFP: 2.5 ± 0.6 branches; p < 0.01) and SRF-deficient (GFP: 1.1 ± 0.2 branches; SRF-ΔNLS-GFP: 1.6 ± 0.3 branches; p < 0.1) neurons (arrows in Fig. 6F,H). Induction of secondary neurite formation in vitro may reflect a molecule's potential to increase axon sprouting during regeneration in vivo. Therefore, cytoplasmic SRF might stimulate sprout protrusion of transected neurons in vivo (Fig. 4).

We also investigated embryonic (Fig. 6I,J) and adult DRG neurons (data not shown) reflecting more closely regeneration models of PNS lesion. In line with results on CNS neurons (Fig. 6C–H), SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 6J) increased neurite growth also of embryonic (Fig. 6I; quantified in Fig. 6K,L) and adult (data not shown) DRG neurons compared with GFP control.

Therefore, cytoplasmic SRF stimulated neuron number, neurite growth, neurite branching, F-actin abundance and affected growth cone shape of CNS and PNS neurons. These in vitro findings suggest that cytoplasmic SRF may contribute to nerve fiber regrowth during axon regeneration by modulation of neuronal motility and morphology.

Modulation of cofilin abundance and subcellular localization during axon regeneration in vivo

Cytoplasmic SRF modulates neuronal motility and the structure of F-actin-rich growth cones (Fig. 6) indicating that cytoplasmic SRF might interact with the actin cytoskeleton. In SRF-deficient neurons, cofilin phosphorylation but not total cofilin expression levels are upregulated. (Alberti et al., 2005). Notably, cofilin is targeted by myelin-associated regeneration inhibitors in vitro (Hsieh et al., 2006). However so far, cofilin expression and phosphorylation was to the best of our knowledge not analyzed after axon injury in vivo. Herein, we analyzed whether cytoplasmic SRF might modulate cofilin's phosphorylation, expression and localization upon facial nerve injury (Fig. 7). For this, we performed immunohistochemistry of cofilin and inactivated phosphorylated cofilin (P-cofilin) three days after injury in both Ad-GFP and Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP infected animals (n ≥ 4 animals/condition; Fig. 7).

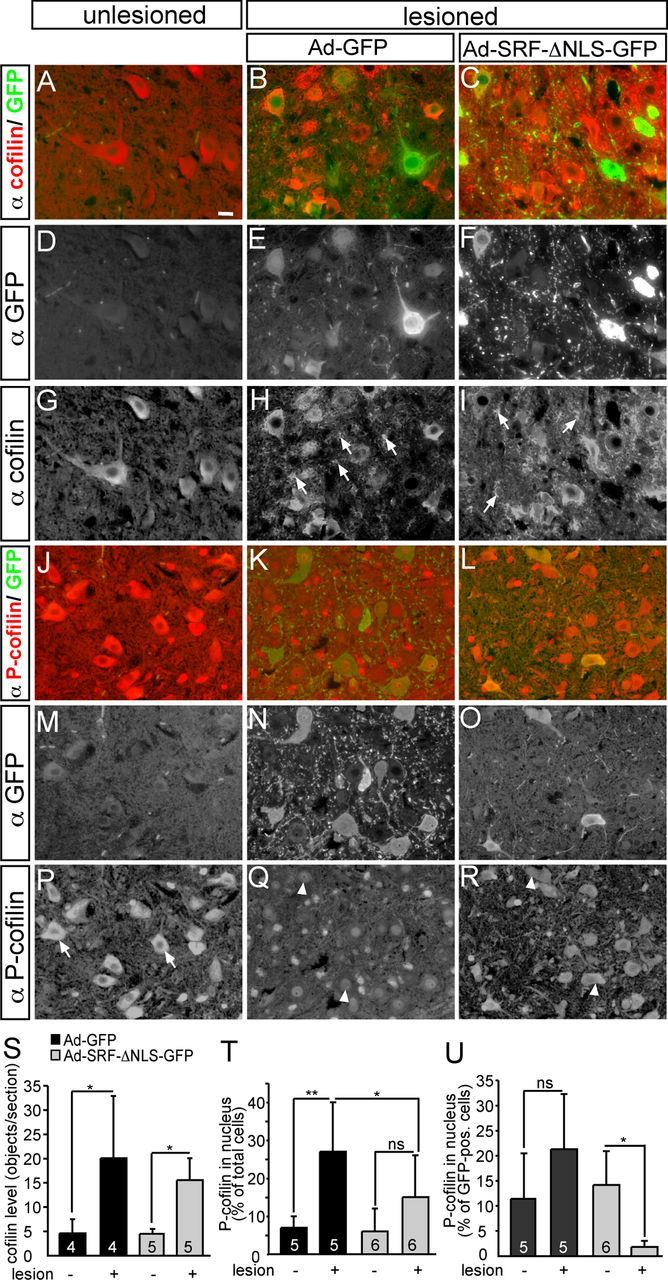

Figure 7.

Expression of cofilin and P-cofilin upon facial nerve injury. A–I, Unlesioned (A, D, G) and lesioned (B, C, E, F, H, I) facial motoneurons were stained for cofilin expression 3 d after facial nerve injury and infection with either Ad-GFP (B, E, H) or Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (C, F, I). In unlesioned motoneurons, cofilin (A, G) was mainly localized to the cell bodies and proximal nerve fibers. Upon facial nerve injury, cofilin was localized between cell bodies in structures reminiscent of axonal sprouts (H, I, arrows). No difference in this cofilin staining was observed when virus types were compared. J–R, In control motoneurons (J, M, P), P-cofilin was mainly associated with cell bodies (P, arrows). Upon lesion in Ad-GFP-infected animals (K, N, Q), P-cofilin was found in the nuclei in a subpopulation of motoneurons (Q, arrowheads, and see quantification in T, U). In contrast, this nuclear P-cofilin staining was reduced in motoneuronsexpressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (L, O, R). S, Quantification of cofilin signals in the region in between cell bodies in the different conditions. T, U, Quantification of nuclear P-cofilin localization in all (T) or GFP-positive (U) cells only. Scale bars: A–R, 10 μm.

First of all, we analyzed expression and localization of total cofilin (Fig. 7A–I,S). In unlesioned facial motoneurons, cofilin was predominantly found in cell bodies and proximal nerve fibers regardless of virus type (Fig. 7A,G). Notably, facial nerve injury induced strong cofilin signals in areas between motoneuron cell bodies, occupied by nerve fibers. This suggests a potential cofilin staining on axonal sprouts (Fig. 7H,I, arrows; quantified in Fig. 7S). This cofilin expression pattern upon facial nerve lesion was comparable between Ad-GFP- (Fig. 7B,H) and Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 7C,I)-infected animals (see also Fig. 7S). In these stainings, we could not discern whether total cofilin levels were rising after facial nerve injury or if a constant cofilin abundance was relocalized from cell bodies to the periphery after lesion. However, cofilin immunoblotting of facial nucleus protein lysates or cofilin staining in the facial nerve (see below and note; Fig. 8) supports induction of cofilin upon lesion.

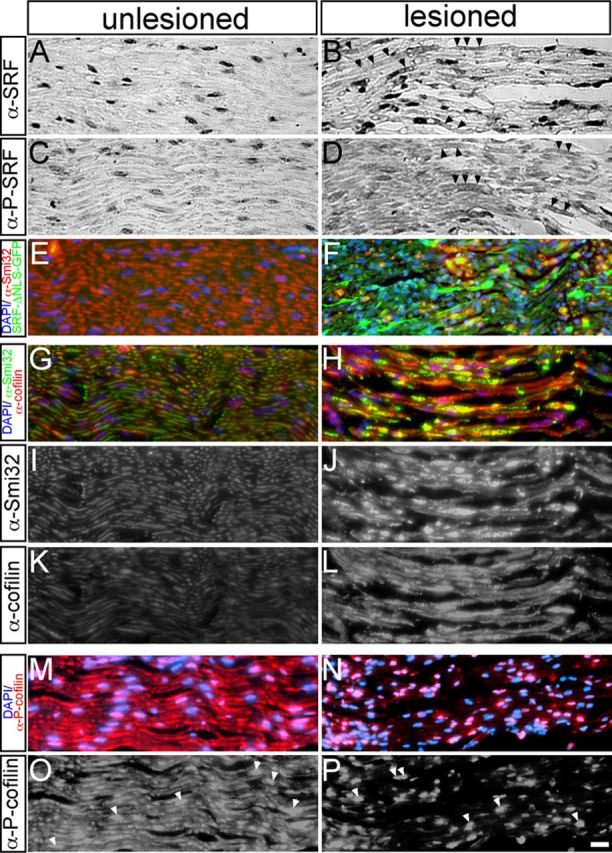

Figure 8.

Analysis of SRF and cofilin expression in the axotomized facial nerve. Facial nerves were analyzed 1 d (A–D, G–P) or 4 d (E–F) after axotomy of uninfected animals (A–D, G–P) or of animals infected with Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (E, F). A–D, SRF (A, B) or P-SRF (C, D) were restricted to nuclei of cells surrounding the unlesioned facial nerve (A, C). Upon axotomy, SRF (B) and P-SRF (D) were also present in the facial nerve (see arrowheads in B, D). E, F, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP labeled via its GFP tag in green was present in the infected and axotomized facial nerve (F), but not in the unlesioned control nerve (E). G–L, Upon lesion, Smi32 (J) and cofilin (L) abundance in facial nerve axons was upregulated compared with intact nerves (I, K). G and H are merged images of of I–L. M–P, P-cofilin was present in unlesioned facial nerve axons and nuclei of surrounding cells (M and arrowheads in O). Upon axotomy, P-cofilin was reduced in the nerve, whereas P-cofilin abundance in nuclei persisted (N, P). Scale bars: A–P, 20 μm.

Next, we inspected P-cofilin (phosphorylated at Ser-3) abundance upon facial nerve injury (Fig. 7J–R,T,U). In unlesioned facial motoneurons (Fig. 7J,P), P-cofilin was found in the cytoplasm regardless of virus type (Fig. 7P, arrows). Upon lesion, P-cofilin entered the nucleus of a subpopulation of Ad-GFP-infected motoneurons (Fig. 7K and Fig. 7Q, arrowheads). This cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation of P-cofilin was reduced in motoneurons expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 7L,O,R), as well as in the total motoneuron population (quantified in Fig. 7T,U). Therefore, P-cofilin was retained in the cytoplasm of many motoneurons of Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-GFP-infected animals (Fig. 7R, arrowheads). In addition to P-cofilin subcellular localization, we also tried to investigate differences in P-cofilin expression levels between GFP- and SRF-ΔNLS-GFP-expressing neurons. However, in part due to the subcellular P-cofilin relocalization, it was difficult to quantify changes in P-cofilin levels by immunofluorescence (but see Figs. 8, 9).

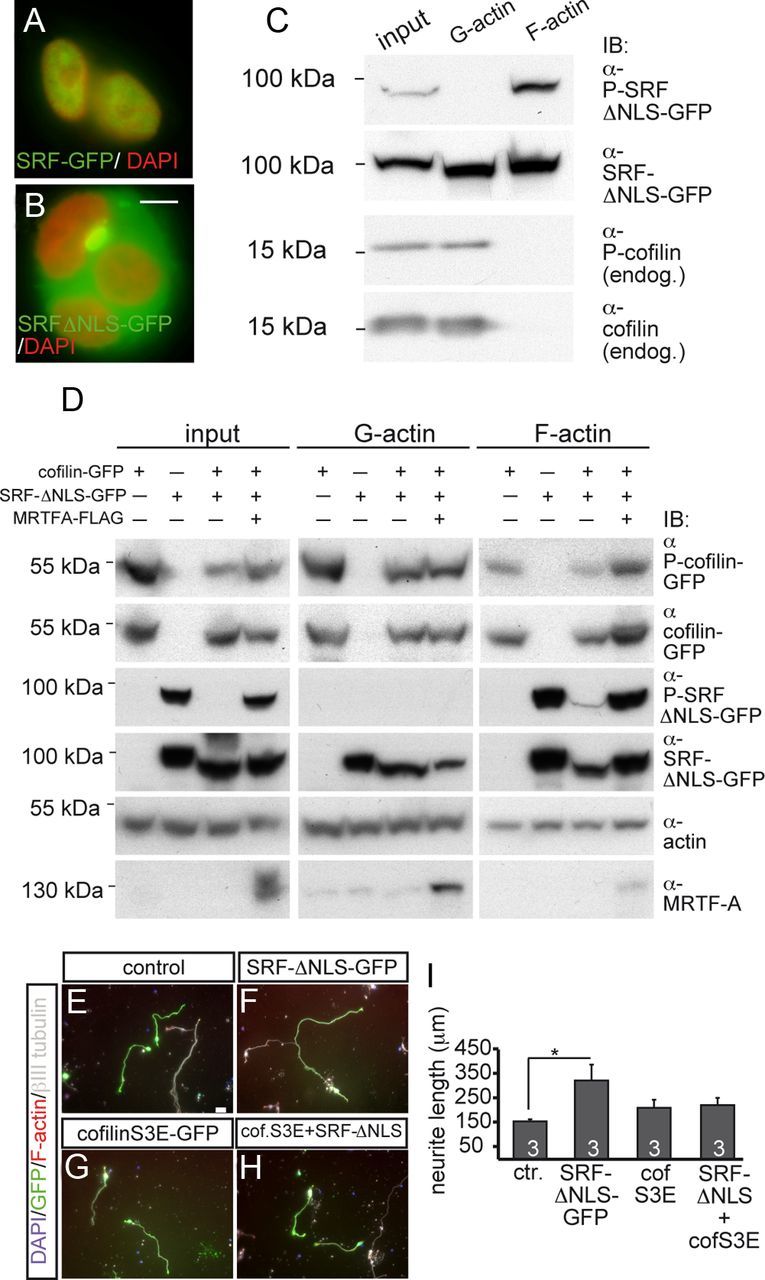

Figure 9.

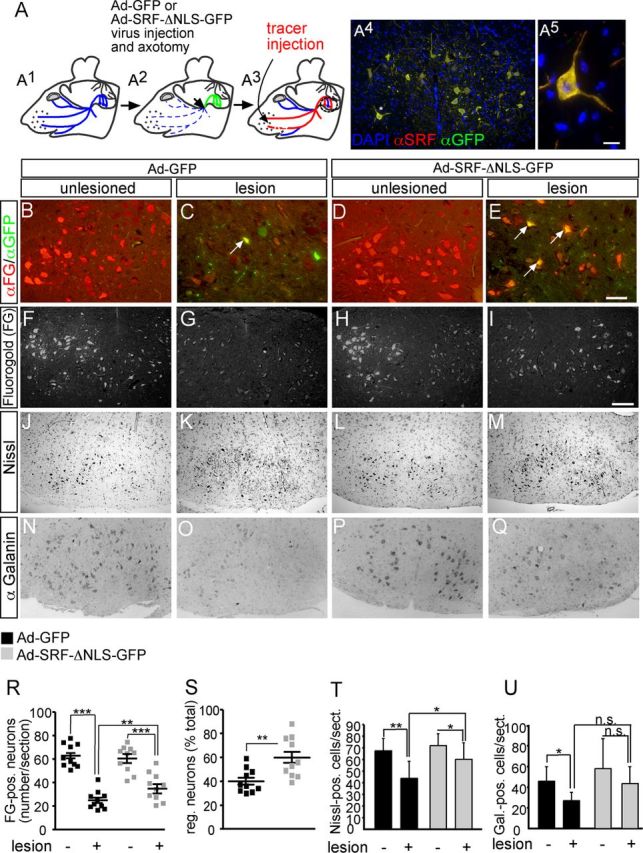

Cytoplasmic SRF and cofilin mutually regulate their phosphorylation and interact in neurite growth in vitro. A, B, In HEK293 cells, SRF-GFP (A) was nucleus restricted, whereas SRF-ΔNLS-GFP showed cytoplasmic localization (B). C, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP was localized to G-actin and F-actin in HEK293 cells. However, serine 103 phosphorylation of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (P-SRF) was only found in F-actin. Endogenous cofilin and P-cofilin were restricted to the G-actin fraction. D, HEK293 cells overexpressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP, wild-type cofilin-GFP, or MRTF-A individually or in combination were subjected to fractionation into G-actin and F-actin. Coexpression of cofilin and SRF-ΔNLS-GFP reduced P-cofilin levels in input, G-actin, and F-actin samples compared with P-cofilin levels in samples expressing cofilin alone. MRTF-A counteracted the reduction of P-cofilin levels induced by cytoplasmic SRF. P-SRF is only present in input and the F-actin samples, but not the G-actin fraction. Cofilin reduced P-SRF levels compared with P-SRF levels in samples expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP alone. MRTF-A elevated P-SRF levels suppressed by cofilin. Total actin levels served as a loading control. E–H, In primary neurons, SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (F) increased neurite length compared with control (E). Coexpression of cofilinS3E-GFP with SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (H) reduced neurite length to control levels. CofilinS3E-GFP (G) alone did not obviously alter neurite length. (I) Quantification of neurite length in the different conditions. Scale bars: A, B, 5 μm; E–H, 20 μm.

In summary, we observed strong cofilin presence in areas occupied by nerve fibers upon facial nerve injury. Further, we demonstrate nuclear entry of P-cofilin upon nerve lesion, a process reduced upon expression of cytoplasmic SRF.

Analysis of SRF and cofilin in the axotomized facial nerve

Above we observed SRF, P-SRF, and cofilin localization in the cytoplasm of transected motoneurons in the facial nucleus (Figs. 3, 7). These findings suggest the presence of SRF, P-SRF, and cofilin also in the facial nerve. To determine to what extent these molecules might enter the facial nerve upon axotomy, we performed staining of longitudinal facial nerve sections at 1 d (Fig. 8A–D,G–P) or 4 d (Fig. 8E,F) after lesion (n = 5 animals).

In unlesioned facial nerves, SRF (Fig. 8A) or P-SRF (Fig. 8C) was restricted to nuclei of cells surrounding the facial nerve (e.g., Schwann cells). Upon facial nerve axotomy, SRF (Fig. 8B) and P-SRF (Fig. 8D) were also found in stretches of the facial nerve (labeled by arrowheads). Therefore, SRF and P-SRF were also present in the lesioned facial nerve, although expression levels in the nerve appeared overall weaker than in the facial nucleus (Fig. 3).

In addition to endogenous SRF, we confirmed the presence of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP in the lesioned (Fig. 8F, green), but not intact (Fig. 8E), facial nerve of an Ad-SRF-ΔNLS-infected animal.

In the facial nucleus, we observed a potential cofilin signal on axonal sprouts after axotomy (Fig. 7H,I). Inspection of the facial nerve revealed upregulation of cofilin in Smi32-positive facial nerves upon lesion (Fig. 8H,J,L) compared with unlesioned nerves (Fig. 8G,I,K). Interestingly, a corresponding P-cofilin staining showed reduction of P-cofilin levels in the facial nerve upon axotomy (Fig. 8N,P) compared with unlesioned nerves (Fig. 8M,O). Similar to observations made in facial motoneurons (Fig. 7), P-cofilin was also present in the nuclei of cells surrounding the facial nerve axons (Fig. 8O,P, arrowheads).

In summary, these findings suggest upregulation of cofilin—most likely in its unphosphorylated active form—in the axotomized facial nerve.

Cytoplasmic SRF reciprocally interacts with cofilin

Thus far, we had observed modulation of P-cofilin subcellular localization by cytoplasmic SRF (Fig. 7). Because regulation of cofilin phosphorylation is impaired in SRF-deficient mice (Alberti et al., 2005), we addressed whether a cytoplasmic SRF localization might contribute to cofilin phosphorylation. To test this possibility, HEK293 cells were subjected to biochemical analysis (n = 4 experiments; Fig. 9). Similar to neurons (Fig. 6), SRF-ΔNLS-GFP was confined to the cytoplasm of HEK293 cells (Fig. 9B). Because cofilin associates with the actin cytoskeleton, we performed actin fractionation into G- and F-actin. We investigated both endogenous cofilin (Fig. 9C) and overexpressed cofilin-GFP (Fig. 9D). Endogenous cofilin and P-cofilin were mainly present in the G-actin fraction and were barely detectable in the F-actin fraction of HEK293 cells (Fig. 9C) and primary neurons (data not shown). Due to this absence of endogenous cofilin and P-cofilin from F-actin (Fig. 9C), we performed overexpression of wild-type cofilin-GFP (Fig. 9D). Now, cofilin and P-cofilin were detectable in the F-actin fraction, albeit still at a lower level than in the G-actin fraction (Fig. 9D). Next, the impact of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP overexpression on cofilin phosphorylation was analyzed. In samples coexpressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP along with cofilin-GFP, cytoplasmic SRF decreased P-cofilin levels (representing inactive cofilin) in the input, G-actin, and F-actin fractions compared with samples expressing cofilin-GFP alone (Fig. 9D). This suggests that overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF activates cofilin. Coexpression of the SRF cofactor MRTF-A counteracted downregulation of P-cofilin levels by cytoplasmic SRF. Now, P-cofilin levels in input and F-actin samples, but not so much in the G-actin sample, were increased (Fig. 9D).

In contrast to the preferential localization of cofilin with G-actin (Fig. 9C,D), total SRF levels were reproducibly elevated in the F-actin fraction of HEK293 cells (Fig. 9C,D) and primary neurons (data not shown). This result corresponds with the colocalization of cytoplasmic SRF and F-actin in growth cones (Fig. 6).

Nuclear SRF is phosphorylated at Ser-103 (Janknecht et al., 1992; Rivera et al., 1993; Heidenreich et al., 1999), whereas phosphorylation of cytoplasmic SRF has not been reported so far. We now provide the first data also showing phosphorylation of cytoplasmic SRF (Fig. 9C,D). Interestingly, in both HEK293 cells (Fig. 9C,D) and primary neurons (data not shown), cytoplasmic SRF was phosphorylated, but only when present in the F-actin, not in the G-actin, fraction. Therefore, cofilin and P-SRF were largely complementarily localized to G-actin and F-actin, respectively (Fig. 9C). This indicates that mainly dephosphorylated SRF, but not P-SRF, has access to cofilin regulation in the G-actin fraction (see summary in Fig. 10B).

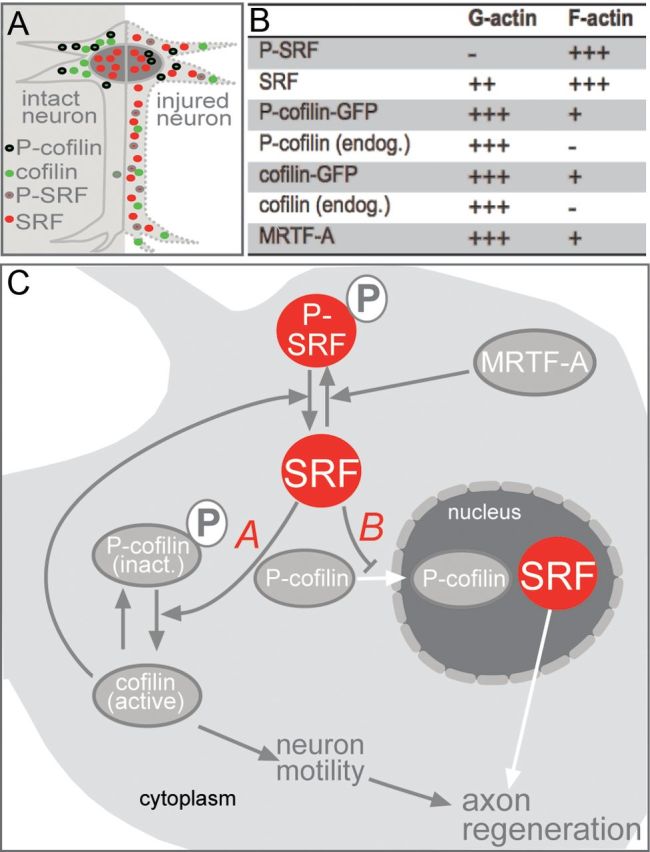

Figure 10.

Summary of the role of SRF in axon regeneration. A, In intact neurons (left), SRF is present in the nucleus, whereas cofilin and P-cofilin are found in the cytoplasm. Upon neuronal injury (right), SRF is present in the nucleus and cytoplasm. P-SRF is mainly localized to the cytoplasm. Cofilin localizes to distal neurite parts, suggesting its presence in axonal sprouts. P-cofilin enters the nucleus of a subpopulation of injured motoneurons. B, Table depicting localization of SRF, cofilin, and MRTF-A in G-actin versus F-actin fractions of HEK293 cells. +++, strongest localization levels; +, weaker localization levels; -, complete absence. C, Mechanisms for the impact of cytoplasmic SRF on axon regeneration. For mechanism A, cytoplasmic SRF is involved in dephosphorylation and thereby activation of cofilin. This subsequently alters actin dynamics and thereby neuronal motility processes relevant for stimulating axon regeneration. Cofilin in turn also adjusts the SRF phosphorylation status. MRTF-A enhances P-SRF levels. For mechanism B, cytoplasmic SRF reduces cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation of P-cofilin.

Above, we observed suppression of P-cofilin by cytoplasmic SRF (Fig. 9D). The reverse scenario, regulation of P-SRF levels by cofilin, also holds true. In samples expressing cofilin-GFP together with SRF-ΔNLS-GFP, P-SRF levels in the input and F-actin fraction were strongly reduced compared with samples expressing SRF-ΔNLS-GFP alone (Fig. 9D). This downregulation of cytoplasmic P-SRF by cofilin was prevented upon coexpression of MRTF-A (Fig. 9D). This result suggests that cofilin and MRTF-A modulate the phosphorylation status and perhaps thereby the function of cytoplasmic SRF. For this, cytoplasmic SRF might form a complex with MRTF-A, actin, and cofilin to fulfill its functions. Indeed, such complex formation appeared possible because MRTF-A, actin, and cofilin were present in immunoprecipitates directed against cytoplasmic SRF (data not shown).

Finally, we analyzed whether this biochemical interaction of cytoplasmic SRF with cofilin affects cell function (Fig. 9E–I). Cytoplasmic SRF suppressed cofilin phosphorylation, likely resulting in cofilin activation (Fig. 9D). To address whether such potential activation of cofilin by cytoplasmic SRF has an impact on neurite growth, we investigated whether cytoplasmic SRF stimulates neurite outgrowth in the presence of a phosphomimetic inactive cofilin mutant, cofilinS3E-GFP (Beck et al., 2012). As before (Fig. 6), SRF-ΔNLS-GFP (Fig. 9F) stimulated neurite length of primary cerebellar neurons compared with control (Fig. 9E) or cofilin-S3E-GFP-expressing neurons (Fig. 9G; quantified in Fig. 9I). Coexpression of SRF-ΔNLS-GFP with cofilinS3E-GFP (Fig. 9H) decreased neurite outgrowth to control levels.

This result suggests the formation of a functional unit consisting of cytoplasmic SRF and cofilin relevant to neurite growth in vitro.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered impaired axon regeneration upon SRF ablation from facial motoneurons (Figs. 1, 2). In addition, in wild-type mice, our histological analysis revealed both nuclear and cytoplasmic SRF localization in the majority of injured motoneurons (Fig. 3) and the facial nerve (Fig. 8 and see summary in Fig. 10A). Therefore, SRF might contribute to axon regeneration via both nuclear gene expression and a novel cytoplasmic function. So far, SRF has primarily been considered to be a nucleus-resident gene regulator. However, consistent with our findings here, a few studies already indicated extranuclear SRF localizations in neurons (Stringer et al., 2002) and other cells (Gauthier-Rouvière et al., 1995; Camoretti-Mercado et al., 2000; Phiel et al., 2001; Beqaj et al., 2002; Kaplan-Albuquerque et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2003; Sarkar et al., 2011).

What is the contribution of such cytoplasmic SRF in relation to nuclear SRF in axon regeneration? Previously, we reported that nucleus-restricted, constitutively active SRF enhanced motoneuron survival but not axon regeneration (Stern et al., 2012). This suggests that nuclear SRF is not sufficient as sole regeneration stimulating factor. In contrast, the current results favor an important role of cytoplasmic SRF in axon regeneration. This is supported by overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF enhancing facial nerve regeneration in vivo (Fig. 4). Cytoplasmic SRF had comparably little influence on SRF target gene abundance (Fig. 5), arguing against cytoplasmic SRF-stimulating axon regeneration by a transcriptional control mechanism. Instead, our data favor a mechanism by which cytoplasmic SRF can directly impinge on cytoskeletal dynamics related to neuronal motility. Using primary neurons, we observed stimulation of various parameters of neuronal morphology and motility by cytoplasmic SRF, including neurite growth and growth cone dynamics (Fig. 6). In addition, cytoplasmic SRF rescued neurite growth inhibition inflicted by SRF deficiency, as also reported previously for wild-type SRF-GFP (Beck et al., 2012). Mechanistically, both nuclear and cytoplasmic SRF appear to modulate cofilin activity to modulate neurite outgrowth. For this, nuclear SRF exerts a transcriptional mechanism to adjust cofilin activity via regulation of CDK5-PAK-Lim kinase signaling (Mokalled et al., 2010). In contrast, as suggested by our data, cytoplasmic SRF might adjust cofilin phosphorylation by complex formation with cofilin in the cytoplasm. However, the complete mechanism of cytoplasmic SRF's interaction with cofilin remains to be further elucidated.

Cytoplasmic SRF's potential to increase branch formation (Fig. 6), an actin dynamics-controlled process connected to axonal sprouting, might immediately apply to facial nerve regeneration in vivo. So far, an interaction of SRF with actin dynamics in the cytoplasm has not been reported, whereas this is well documented in the nucleus (Vartiainen et al., 2007). In this study, we have started to elucidate two mechanisms by which cytoplasmic SRF might impinge on cytoskeletal dynamics (see mechanism A and B summary in Fig. 10C).

Mechanism A relates to the downregulation of P-cofilin levels by cytoplasmic SRF (Fig. 9D). Cofilin is essential for neuronal actin dynamics, as uncovered recently in cofilin mouse mutants suffering from neuronal motility and morphology defects (Flynn et al., 2012). Therefore, cytoplasmic SRF might stimulate cofilin dephosphorylation (and thereby activation) and enhance cofilin-mediated actin severing in growth cones. Therefore, remodeling of microfilaments in growth cones, particularly filopodia, might be stimulated and the cellular growth machinery for axon elongation and branching might be reinstalled. Such successful stimulation of neuronal motility processes, including axon elongation and sprout formation, might facilitate axon regeneration (Fig. 10C). Consistent with this model, here we provide in vitro data demonstrating that cytoplasmic SRF's potential to stimulate neuronal motility depends on cofilin (Fig. 9E–I).

Mechanism B encompasses the finding that cytoplasmic SRF adjusts cofilin function by regulation of cofilin's subcellular localization (Fig. 10C). Cofilin is involved in a stress response including cytoplasm to nuclear relocalization during neurodegeneration (Bamburg et al., 2010; Munsie et al., 2011; Munsie et al., 2012). Consistent with these findings, we observed a nuclear entry of P-cofilin in injured motoneurons prone to degeneration to some extent (Moran and Graeber, 2004; Fig. 7). Overexpression of cytoplasmic SRF reduced the number of motoneurons with nuclear P-cofilin abundance and might thereby counteract such a nuclear cofilin stress response associated with neurodegeneration. Consistent with such a scenario is the finding that cytoplasmic SRF also prevented loss of facial motoneurons upon injury (Fig. 4). In addition to P-cofilin, we observed induction of total cofilin protein abundance in axonal sprouts of axotomized facial motoneurons (Fig. 7) and in the lesioned facial nerve (Fig. 8). Because this cofilin abundance was not phosphorylated (Figs. 7, 8), it is tempting to speculate that this cofilin is present in an active form in axonal sprouts during facial nerve regeneration. Such activated cofilin present in the facial nerve (Fig. 8) might enhance actin dynamics through its severing activity and thereby modulate F-actin turnover during facial nerve regeneration.

Finally, in this study, we uncovered a novel aspect of SRF's interaction with cofilin. Previous research had focused on the impact of SRF on cofilin function. Now, we present data arguing that the reverse scenario, cofilin modulating SRF function, also holds true. Overexpression of wild-type cofilin (Fig. 9), but not an inactive cofilin mutant (cofilin S3E; data not shown), suppressed SRF phosphorylation. SRF phosphorylation was so far almost exclusively associated with nuclear SRF, for example, by regulating SRF's DNA affinity (Janknecht et al., 1992; Rivera et al., 1993; Heidenreich et al., 1999). However, our data suggest further functions of SRF phosphorylation taking place in the cytoplasm, including modulation of cofilin activity. Notably, reduction of cofilin phosphorylation induced by cytoplasmic SRF corresponded with an almost complete absence of SRF phosphorylation (Fig. 9D). This suggests that dephosphoylated SRF might be a main regulator of cofilin phosphorylation (Figs. 9, 10). Overall, cytoplasmic SRF and cofilin appear to build a mutual regulatory unit. The activity of this SRF-cofilin regulatory loop is further modulated by MRTF-A, the expression of which is altered by axon injury in vivo (Fig. 3).

In summary, we provide data ascribing to SRF an axon-protective and pro-regenerative function upon entering the cytoplasm. It will be interesting to explore whether such cytoplasmic SRF is not only beneficial for PNS but also for CNS regeneration.

Notes

Supplemental material for this article is available at https://www.uni-ulm.de/fileadmin/website_uni_ulm/med.inst.100/website/AGKnoell/Supp_material_Stern_et_al.pdf. The supplement includes immunoblotting data from isolated control and lesioned facial nuclei infected with Ad-GFP or infected with Ad-SRF-?NLS-GFP. This biochemical analysis confirms upregulation of total cofilin levels upon lesion. This material has not been peer reviewed.

Footnotes

B.K. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and through grants from the Schram, Gottschalk, and Gemeinnützige Hertie Foundation. The doctoral thesis of S.S. is supported in part by the Gottschalk Foundation. A.N. acknowledges support by the DFG (Grant 120/12-4). We thank Erika Schmidt and Ulrike Sebert for helping with the production of viral particles and protein biochemistry.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alberti S, Krause SM, Kretz O, Philippar U, Lemberger T, Casanova E, Wiebel FF, Schwarz H, Frotscher M, Schütz G, Nordheim A. Neuronal migration in the murine rostral migratory stream requires serum response factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6148–6153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501191102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamburg JR, Bernstein BW, Davis RC, Flynn KC, Goldsbury C, Jensen JR, Maloney MT, Marsden IT, Minamide LS, Pak CW, Shaw AE, Whiteman I, Wiggan O. ADF/Cofilin-actin rods in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:241–250. doi: 10.2174/156720510791050902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H, Flynn K, Lindenberg KS, Schwarz H, Bradke F, Di Giovanni S, Knöll B. Serum Response Factor (SRF)-cofilin-actin signaling axis modulates mitochondrial dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2523–2532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208141109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beqaj S, Jakkaraju S, Mattingly RR, Pan D, Schuger L. High RhoA activity maintains the undifferentiated mesenchymal cell phenotype, whereas RhoA down-regulation by laminin-2 induces smooth muscle myogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradke F, Fawcett JW, Spira ME. Assembly of a new growth cone after axotomy: the precursor to axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoretti-Mercado B, Liu HW, Halayko AJ, Forsythe SM, Kyle JW, Li B, Fu Y, McConville J, Kogut P, Vieira JE, Patel NM, Hershenson MB, Fuchs E, Sinha S, Miano JM, Parmacek MS, Burkhardt JK, Solway J. Physiological control of smooth muscle-specific gene expression through regulated nuclear translocation of serum response factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30387–30393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoretti-Mercado B, Fernandes DJ, Dewundara S, Churchill J, Ma L, Kogut PC, McConville JF, Parmacek MS, Solway J. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta-enhanced serum response factor-dependent transcription by SMAD7. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20383–20392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk A, Hellal F, Enes J, Bradke F. Disorganized microtubules underlie the formation of retraction bulbs and the failure of axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9169–9180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0612-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn KC, Hellal F, Neukirchen D, Jacob S, Tahirovic S, Dupraz S, Stern S, Garvalov BK, Gurniak C, Shaw AE, Meyn L, Wedlich-Soldner R, Bamburg JR, Small JV, Witke W, Bradke F. ADF/cofilin-mediated actin retrograde flow directs neurite formation in the developing brain. Neuron. 2012;76:1091–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier-Rouvière C, Vandromme M, Lautredou N, Cai QQ, Girard F, Fernandez A, Lamb N. The serum response factor nuclear localization signal: general implications for cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase activity in control of nuclear translocation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:433–444. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich O, Neininger A, Schratt G, Zinck R, Cahill MA, Engel K, Kotlyarov A, Kraft R, Kostka S, Gaestel M, Nordheim A. MAPKAP kinase 2 phosphorylates serum response factor in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14434–14443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T, Blume A, Buschmann T, Georgakopoulos E, Winter C, Schmid W, Hsieh TF, Zimmermann M, Gass P. Expression of activating transcription factor-2, serum response factor and cAMP/Ca response element binding protein in the adult rat brain following generalized seizures, nerve fibre lesion and ultraviolet irradiation. Neuroscience. 1997;81:199–212. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00170-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh SH, Ferraro GB, Fournier AE. Myelin-associated inhibitors regulate cofilin phosphorylation and neuronal inhibition through LIM kinase and Slingshot phosphatase. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1006–1015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2806-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janknecht R, Hipskind RA, Houthaeve T, Nordheim A, Stunnenberg HG. Identification of multiple SRF N-terminal phosphorylation sites affecting DNA binding properties. EMBO J. 1992;11:1045–1054. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan-Albuquerque N, Garat C, Desseva C, Jones PL, Nemenoff RA. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB-mediated activation of Akt suppresses smooth muscle-specific gene expression through inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase and redistribution of serum response factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39830–39838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöll B, Nordheim A. Functional versatility of transcription factors in the nervous system: the SRF paradigm. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöll B, Kretz O, Fiedler C, Alberti S, Schütz G, Frotscher M, Nordheim A. Serum response factor controls neuronal circuit assembly in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:195–204. doi: 10.1038/nn1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HW, Halayko AJ, Fernandes DJ, Harmon GS, McCauley JA, Kocieniewski P, McConville J, Fu Y, Forsythe SM, Kogut P, Bellam S, Dowell M, Churchill J, Lesso H, Kassiri K, Mitchell RW, Hershenson MB, Camoretti-Mercado B, Solway J. The RhoA/Rho kinase pathway regulates nuclear localization of serum response factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:39–47. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0206OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PP, Ramanan N. Serum response factor is required for cortical axon growth but is dispensable for neurogenesis and neocortical lamination. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16651–16664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3015-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makwana M, Werner A, Acosta-Saltos A, Gonitel R, Pararajasingham A, Ruff C, Rumajogee P, Cuthill D, Galiano M, Bohatschek M, Wallace AS, Anderson PN, Mayer U, Behrens A, Raivich G. Peripheral facial nerve axotomy in mice causes sprouting of motor axons into perineuronal central white matter: time course and molecular characterization. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:699–721. doi: 10.1002/cne.22240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier C, Anastasiadou S, Knöll B. Ephrin-A5 suppresses neurotrophin evoked neuronal motility, ERK activation and gene expression. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokalled MH, Johnson A, Kim Y, Oh J, Olson EN. Myocardin-related transcription factors regulate the Cdk5/Pctaire1 kinase cascade to control neurite outgrowth, neuronal migration and brain development. Development. 2010;137:2365–2374. doi: 10.1242/dev.047605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LB, Graeber MB. The facial nerve axotomy model. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;44:154–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsie LN, Desmond CR, Truant R. Cofilin nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling affects cofilin-actin rod formation during stress. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3977–3988. doi: 10.1242/jcs.097667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsie L, Caron N, Atwal RS, Marsden I, Wild EJ, Bamburg JR, Tabrizi SJ, Truant R. Mutant huntingtin causes defective actin remodeling during stress: defining a new role for transglutaminase 2 in neurodegenerative disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1937–1951. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN, Nordheim A. Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:353–365. doi: 10.1038/nrm2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AP, Pohl-Guimaraes F, Krahe TE, Filgueiras CC, Lantz CL, Colello RJ, Wang W, Medina AE. Overexpression of serum response factor restores ocular dominance plasticity in a model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2513–2520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5840-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiel CJ, Gabbeta V, Parsons LM, Rothblat D, Harvey RP, McHugh KM. Differential binding of an SRF/NK-2/MEF2 transcription factor complex in normal versus neoplastic smooth muscle tissues. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34637–34650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posern G, Sotiropoulos A, Treisman R. Mutant actins demonstrate a role for unpolymerized actin in control of transcription by serum response factor. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4167–4178. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-05-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G. c-Jun expression, activation and function in neural cell death, inflammation and repair. J Neurochem. 2008;107:898–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Bohatschek M, Da Costa C, Iwata O, Galiano M, Hristova M, Nateri AS, Makwana M, Riera-Sans L, Wolfer DP, Lipp HP, Aguzzi A, Wagner EF, Behrens A. The AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun is required for efficient axonal regeneration. Neuron. 2004;43:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera VM, Miranti CK, Misra RP, Ginty DD, Chen RH, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. A growth factor-induced kinase phosphorylates the serum response factor at a site that regulates its DNA-binding activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6260–6273. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Zhang M, Liu SH, Sarkar S, Brunicardi FC, Berger DH, Belaguli NS. Serum response factor expression is enriched in pancreatic beta cells and regulates insulin gene expression. FASEB J. 2011;25:2592–2603. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern S, Debre E, Stritt C, Berger J, Posern G, Knöll B. A nuclear actin function regulates neuronal motility by serum response factor-dependent gene transcription. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4512–4518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern S, Sinske D, Knöll B. Serum response factor modulates neuron survival during peripheral axon injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:78. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer JL, Belaguli NS, Iyer D, Schwartz RJ, Balasubramanyam A. Developmental expression of serum response factor in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:81–86. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritt C, Knöll B. Serum response factor regulates hippocampal lamination and dendrite development and is connected with reelin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1828–1837. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01434-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritt C, Stern S, Harting K, Manke T, Sinske D, Schwarz H, Vingron M, Nordheim A, Knöll B. Paracrine control of oligodendrocyte differentiation by SRF-directed neuronal gene expression. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:418–427. doi: 10.1038/nn.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen MK, Guettler S, Larijani B, Treisman R. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science. 2007;316:1749–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1141084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialou V, Feng J, Robison AJ, Ku SM, Ferguson D, Scobie KN, Mazei-Robison MS, Mouzon E, Nestler EJ. Serum response factor and cAMP response element binding protein are both required for cocaine induction of DeltaFosB. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7577–7584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1381-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe SR, Alvania RS, Ramanan N, Wood JN, Mandai K, Ginty DD. Serum Response Factor Mediates NGF-Dependent Target Innervation by Embryonic DRG Sensory Neurons. Neuron. 2008;58:532–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebel FF, Rennekampff V, Vintersten K, Nordheim A. Generation of mice carrying conditional knockout alleles for the transcription factor SRF. Genesis. 2002;32:124–126. doi: 10.1002/gene.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhe X, Phan SH, Ullenbruch M, Schuger L. Involvement of serum response factor isoforms in myofibroblast differentiation during bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:583–590. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0315OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]