Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence and/or incidence of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting conditions?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of anxiety in 19 studies was 19.1%, with significant differences in prevalence according to the type of assessment tool used; in a meta-analysis of 36 studies, depression prevalence was 14.3% and was associated with increasing age. No studies included information on incidence of anxiety or depression.

Meaning

The high prevalence of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting conditions highlights the need for improved services to address their psychological needs.

This systematic review and meta-analysis estimates the prevalence of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting conditions.

Abstract

Importance

Children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting conditions experience various challenges that may make them more vulnerable to mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression. However, the prevalence and incidence of anxiety and depression among this population appears to be unknown.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence and/or incidence of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting conditions.

Data Sources

Searches of MEDLINE (PubMed), PsycInfo, and Embase were conducted to identify studies published between January 2000 and January 2018.

Study Selection

Studies were eligible for this review if they provided primary data of anxiety or depression prevalence and/or incidence, included participants aged 5 to 25 years with a life-limiting condition, were conducted in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country, and were available in English.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Random-effects meta-analyses were generated to provide anxiety and depression prevalence estimates. Meta-regression was conducted to analyze associations between study characteristics and each prevalence estimate.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalence of anxiety and depression.

Results

A total of 14 866 nonduplicate articles were screened, of which 37 were included in the review. Of these, 19 studies reported anxiety prevalence, and 36 studies reported depression prevalence. The mean (range) age of participants was 15.4 (6-25) years. The meta-analysis of anxiety prevalence (n = 4547 participants) generated a pooled prevalence estimate of 19.1% (95% CI, 14.1%-24.6%). Meta-regression analysis found statistically significant differences in anxiety prevalence by assessment tool; diagnostic interviews were associated with higher anxiety prevalence (28.5% [95% CI, 13.2%-46.8%]) than self-reported or parent-reported measures (14.9% [95% CI, 10.9%-19.4%]). The depression meta-analysis (n = 5934 participants) found a pooled prevalence estimate of 14.3% (95% CI, 10.5%-18.6%). Meta-regression analysis revealed statistically significant differences in depression prevalence by the mean age of the sample (β = 0.02 [95% CI, 0.01-0.03]; P = .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of anxiety and depression among children, adolescents, and young adults with life-limiting conditions was high, highlighting the need for increased psychological assessment and monitoring. Further research is required to determine the prevalence and incidence of anxiety and depression in a larger sample of children, adolescents, and young adults with a broader range of life-limiting conditions.

Introduction

Mental health problems among young people are a growing public health concern, affecting between 10% and 20% of children and adolescents worldwide.1 National surveys in the United States have found that 3% of children and adolescents have a diagnosis of anxiety, while depression prevalence ranged from 2.1% to 8.1%.2 Furthermore, for three-quarters of adults with long-term mental health problems, onset occurred before age 24 years.3

Growing research of children, adolescents, and young adults suggests a strong link between chronic physical illness and mental health problems.4,5,6 Some chronic conditions are life limiting. These include conditions for which there is no cure that cause death, either directly (eg, Batten disease, Duchenne muscular dystrophy) or through secondary health difficulties associated with the condition (eg, severe cerebral palsy), and those for which curative treatment is possible but may result in failure (eg, cancer, organ failure).7 After diagnosis of a life-limiting condition (LLC), children, adolescents, and young adults may encounter multiple disease-associated challenges, which, coupled with the stressors associated with the period of adolescence, such as puberty and the desire to become independent from one’s parents, makes navigating daily life a potentially challenging endeavor.8,9 For example, regular clinic appointments and hospitalizations can result in children and young people missing school, therefore potentially disrupting both their education and peer relationships.10 These challenges can be exacerbated by physical symptoms resulting from the LLC itself or associated treatment regimens, either through adverse effects, such as fatigue caused by medication, or direct biochemical changes, which have been proposed to be linked to the onset of depression in some patients.11,12 Children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs may also have fears surrounding the unpredictability of their future, including the fear of death, which often make patients unsure if they will be able to achieve future hopes and aspirations.13

The prevalence of LLCs in England rose from 25 per 10 000 in 2000 and 2001 to 32 per 10 000 in 2009 and 2010, with the largest increase in prevalence occurring in young people aged between 16 and 19 years, which likely represents an increase in survival.14 Because chronic physical illness has been found to be associated with an increased risk of mental health problems, the increased prevalence of LLCs among children and young people necessitates the development of services aimed at caring for their psychological needs. This has been recognized in England and Wales by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016 guidelines regarding end-of-life care for infants, children, and young people with LLCs, which highlight the need for research into the range, severity, and context of psychological difficulties among children and young people with LLCs for the subsequent design of effective interventions.15 Therefore, it is crucial that research analyzing the epidemiology of anxiety and depression is systematically reviewed to guide future research and clinical guidance. Consequently, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to estimate the prevalence and incidence of anxiety and depression in children and young people (aged 5-25 years) with a range of LLCs.

Methods

Search Strategy

The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to a review protocol registered on PROSPERO prior to review initiation (identifier: CRD42018088795). Embase, MEDLINE (PubMed), and PsycInfo were searched on January 15, 2018, to identify articles published from January 1, 2000, onward. The search was conducted using both subject headings and free text with the various combinations of the terms children, adolescents, young adults, anxiety, depression, and terms for specific life-limiting conditions, including a full list of all LLC diagnoses (eTable 1 in the Supplement for MEDLINE search strategy).16 Reference lists of identified systematic reviews and all included articles were searched for additional eligible papers. The gray literature was reviewed using an advanced Google search, with the first 50 PDFs obtained screened for eligibility.

Studies were included if (1) they provided primary data of anxiety or depression prevalence or incidence measured using validated assessment tools or coded medical report data, (2) participants were between the ages of 5 and 25 years, (3) participants had been diagnosed with a LLC, (4) the study was published in English or subsequently translated into English, and (5) the study was conducted in a country within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The following types of study designs were excluded: (1) case studies, case series, intervention studies, qualitative studies, systematic reviews, and abstracts; (2) studies that included non-LLC diagnoses and did not report data of non-LLC and LLC subgroups separately; and (3) studies of participants successfully treated for cancer.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts of all studies were screened by the primary reviewer (M.M.B.), with 20% also independently screened by a second reviewer (a nonauthor). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Full texts of all studies deemed potentially eligible were retrieved and reviewed for eligibility by the first reviewer (M.M.B.), with the second reviewer also independently reviewing 20%. For articles in which key data were missing, study authors were contacted. In the case that authors did not reply to this request, the article was not included. Studies investigating the prevalence of anxiety or depression among children and young people with DiGeorge syndrome were excluded at this stage because mental health problems are a component of this condition.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by 1 reviewer (M.M.B.), using an extraction form piloted on 3 eligible studies. Key study characteristics including country of study, study design, recruitment and eligibility criteria, anxiety and depression assessment tool(s), age, and sex were extracted. The number of participants identified by the study as being anxious or depressed was recorded along with the study sample size for the calculation of prevalence. For the calculation of incidence, the number of new cases identified and the person-time used was extracted.

Risk of Bias Assessment

In response to the fact that included studies only reported prevalence, the protocol was amended to use a tool specifically designed to assess bias in prevalence studies.17 The chosen tool consists of 10 questions, which are scored positively or negatively, and according to the total score, each study was characterized as being at low, moderate, or high risk of bias. Any studies deemed to be at high risk of bias were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp) was used to generate meta-analyses for anxiety and depression prevalence. Random-effects meta-analyses were used owing to the high expected heterogeneity between studies. To stabilize variances, study data were first transformed using the double arcsine transformation.18 Study-specific 95% CIs were generated using the exact method. Heterogeneity was analyzed using the I2 statistic. Heterogeneity was first explored through subgroup analysis, using the following categorical study characteristics: (1) LLC diagnostic group (cancer, cystic fibrosis, HIV, thalassemia, neurological conditions, or chronic kidney disease); (2) study location (Europe or the United States); (3) assessment tool (self-report or parent-report questionnaire or diagnostic interview); and (4) risk of bias (low or moderate). Univariate meta-regression models were then conducted to assess the association between study characteristics and the pooled prevalence estimate. Models were generated for each of the aforementioned categorical study characteristics, in addition to the following quantitative study characteristics: sample size, mean age, and percentage of female participants in the sample.

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and the Egger test of bias. A significance level of P < .05 was used throughout.

Results

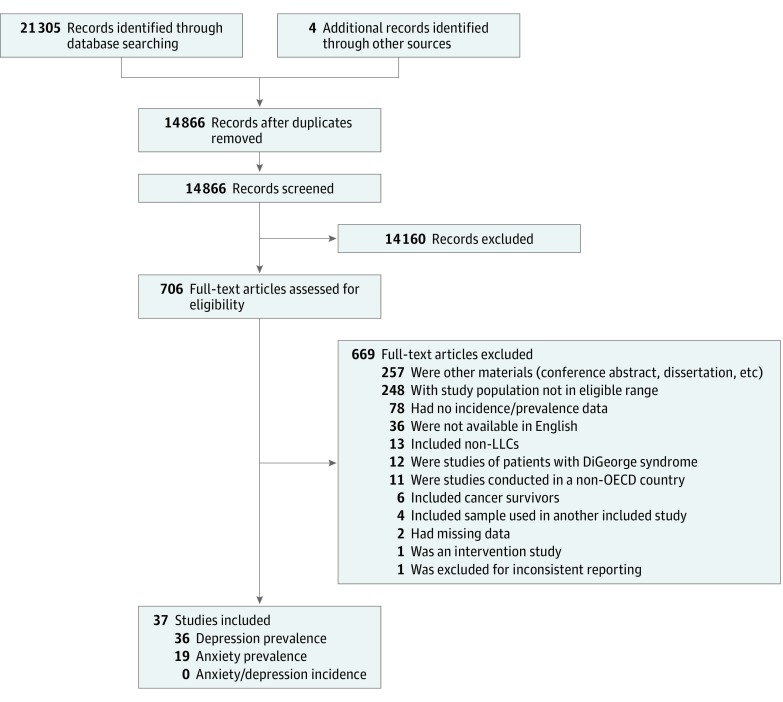

The electronic search identified 14 866 nonduplicate articles, as shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram (Figure 1). The full texts of 709 articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility, resulting in the inclusion of 37 studies.11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 Of the included articles, 19 studies11,19,22,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,36,39,41,42,43,44,45,48,54 reported anxiety prevalence, and 36 studies11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,52,53,54 reported depression prevalence. None reported the incidence of anxiety or depression.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram.

The flow diagram adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses standard. LLC indicates life-limiting conditions; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Study Characteristics

The key characteristics of the 37 included studies are summarized in the Table. In total, 6042 participants were included. Study sample sizes ranged from 20 to 2032 participants, with a median of 50 (interquartile range [IQR], 38-96) participants. The age range of participants was reported in 30 studies,11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,28,31,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,51,52,53 and these ranged from 6 to 25 years overall. The mean (SD) participant age from the 24 studies providing this information was 15.4 (3.2) years. The proportion of female participants in the study sample was reported in 32 studies,11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,40,41,43,44,45,46,47,49,51,52,53,54 with a total of 2432 female participants among 5403 participants (a mean of 45.0%).

Table. Key Characteristics of the 37 Included Studies.

| Source | Location | Total Participants | Age, Mean (SD) [Range], y | No. of Female Participants/No. of Total Participants (%) | Year of Data Collection | Anxiety Prevalence Reported | Depression Prevalence Reported | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | ||||||||

| Hedström et al,11 2005 | Sweden | 56 | NR (NR) [13-19] | 24/56 (43) | 1999-2003 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Matziou et al,21 2008 | Greece | 80 | 11.2 (NR) [6-16] | 35/80 (44) | 2002-2005 | No | Yes | Low |

| Kersun et al,22 2009 | United States | 41 | 15.2 (2.2) [12-19] | 18/41 (44) | NR | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Durualp and Altay,23 2012 | Turkey | 20 | NR (NR) [6-12] | 10/20 (50) | 2010-2011 | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Bemis et al,24 2015 | United States | 151 | 13.5 (2.4) [10-17] | 77/151 (51) | NR | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Rivas-Molina et al,25 2015 | Mexico | 46 | NR (NR) [7-15] | 14/46 (30) | 2012 | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Cystic Fibrosis | ||||||||

| Casier et al,26 2008 | Belgium | 34 | 17.3 (3.1) [NR] | 18/34 (53) | NR | Yes | Yes | Low |

| White et al,27 2009 | United States | 53 | 12.4 (2.6) [9-17] | 31/53 (58) | 1995-1996 | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Smith et al,28 2010 | United States | 39 | 12.0 (3.1) [7-17] | 20/39 (51) | NR | No | Yes | Low |

| Casier et al,29 2011 | Belgium | 40 | 18.4 (2.9) [NR] | 17/40 (43) | NR | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Modi et al,30 2011 | United States | 59 | 15.8 (2.5) [NR] | 27/59 (46) | 2006-2008 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Oliver et al,31 2014 | United States | 72 | 19.1 (3.3) [14-25] | 36/72 (50) | 2010-2011 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Quittner et al,32 2014 | Multinational (Europe and United States) | 1286 | 14.8 (1.7) [NR] | 669/1286 (52) | NR | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Askew et al,33 2017 | United Kingdom | 45 | 20.7 (NR) [17-24] | 18/45 (40) | NR | Yes | Yes | Low |

| HIV | ||||||||

| Pao et al,34 2000 | United States | 34 | 18.5 (NR) [16-21] | 27/34 (79) | NR | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Murphy et al,35 2001 | United States | 213 | NR (NR) [12-18] | NR | 1999-2000 | No | Yes | Low |

| Elliott-DeSorbo et al,36 2009 | United States | 55 | 12.9 (NR) [8-17] | 25/55 (45) | 2001-2005 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Mellins et al,54 2009 | United States | 206 | 12.3 (2.2) [NR] | 105/206 (51) | NR | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Andrinopoulos et al,37 2011 | United States | 166 | NR (NR) [15-24] | 166/166 (100) | 2003-2005 | No | Yes | Low |

| Martinez et al,38 2012 | United States | 60 | 20.6 (2.0) [15-24] | 60/60 (100) | 2003-2005 | No | Yes | Low |

| Nachman et al,39 2012 | United States | 313 | NR (NR) [6-17] | NR | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Salama et al,40 2013 | United States | 59 | 18.8 (NR) [14-23] | 36/59 (61) | 2002-2003 | No | Yes | Low |

| Brown et al,41 2015 | United States | 2032 | 20.3 (NR) (2.1) | 662/2032 (33) | 2009-2012 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Thalassemia | ||||||||

| Clemente et al,42 2002 | Multinational (Europe) | 38 | NR (NR) [6-18] | NR | 1994-1996 | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Aydinok et al,43 2005 | Turkey | 38 | 12.2 (3.3) [6-18] | 20/38 (53) | NR | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Cakaloz et al,44 2009 | Turkey | 20 | 11.1 (3.0) [7-18] | 13/20 (65) | NR | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Adanir et al,45 2017 | Turkey | 24 | 13.6 (2.1) [12-18] | 11/24 (46) | NR | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Neurological Conditions | ||||||||

| Laufersweiler-Plass et al,19 2003 | Germany | 96 | 11.2 (NR) [6-18] | 49/96 (51) | NR | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Bäckman et al,46 2005 | Finland | 27 | NR (NR) [9-21] | 14/27 (52) | NR | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Amato et al,47 2008 | Italy | 63 | 15.3 (2.5) [8-17] | 33/63 (52) | NR | No | Yes | Low |

| Amato et al,48 2010 | Italy | 39 | NR (NR) [12-20] | NR | NR | Yes | No | Low |

| Till et al,20 2012 | Canada | 31 | 16.1 (NR) [12-19] | 23/31 (74) | NR | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Elsenbruch et al,49 2013 | Germany | 50 | 15.4 (0.6) [8-23] | 0/50 | 2009-2011 | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Parrish et al,50 2013 | United States | 36 | NR (NR) [NR] | NR | NR | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | ||||||||

| Kogon et al,51 2013 | United States | 44 | NR (NR) [7-18] | 13/44 (30) | 2011-2012 | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Kogon et al,52 2016 | United States | 344 | NR (NR) [6-17] | 142/344 (41) | 2005-2008 | No | Yes | Low |

| Kilicoglu et al,53 2016 | Turkey | 32 | NR (NR) [8-18] | 19/32 (59) | 2014 | No | Yes | Low |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

A total of 18 studies22,24,27,28,30,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,50,51,52,54 (49%) were from the United States, and 15 studies11,19,21,23,26,29,33,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,53 (41%) were from Europe. In addition, 1 study20 was from Canada, 1 study25 was from Mexico, and 2 studies (5%) were multinational (1 in European countries and the United States32 and 1 in European countries only42).

Of the 37 included studies, 6 studies11,21,22,23,24,25 (16%) assessed children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer (n = 394), 8 studies26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 (22%) included children, adolescents, and young adults with cystic fibrosis (n = 1628), and a further 9 studies34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,54 (24%) assessed children, adolescents, and young adults with HIV (n = 3138). Children, adolescents, and young adults with thalassemia were included in 4 studies42,43,44,45 (11%; n = 120), while 7 studies19,20,46,47,48,49,50 (19%; n = 342) assessed children, adolescents, and young adults with neurological conditions, and 3 studies51,52,53 (8%; n = 420) included children, adolescents, and young adults with chronic kidney disease.

Risk of Bias Assessment

No studies were deemed to be at high risk of bias, 14 studies19,20,23,24,25,27,34,43,44,45,46,49,50,51 (38%) were at moderate risk of bias, and 23 studies11,21,22,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,47,48,52,53,54 (62%) were at low risk of bias. Only 1 study11 scored positively on the question regarding minimizing the likelihood of nonresponse bias (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Anxiety and Depression Assessment Tools

A total of 10 different assessment tools were used to measure the prevalence of anxiety, while 15 different assessment tools were used to assess depression prevalence (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The most common assessment tool for measuring anxiety was the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, which was used in 7 studies11,26,29,30,31,32,33 of the 19 studies in this group (37%), whereas the Children’s Depression Inventory was the most common depression assessment tool, having been used in 9 studies21,23,25,28,46,47,51,52,53 of the 36 in this group (25%). Parent-report measures were used in 3 studies.19,20,54

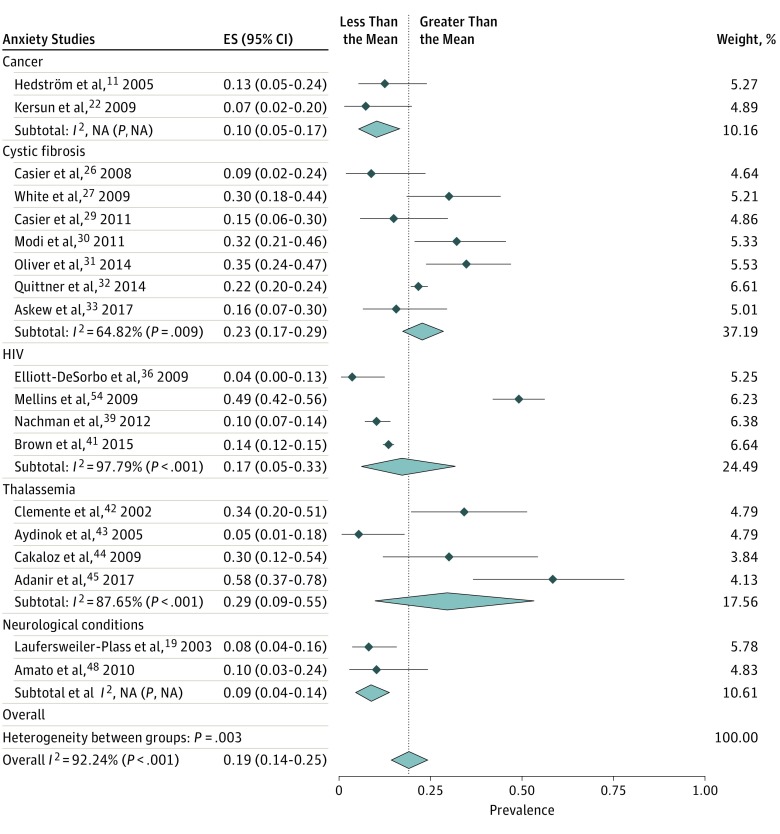

Prevalence of Anxiety

The prevalence of anxiety was reported in 19 studies,11,19,22,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,36,39,41,42,43,44,45,48,54 with a total of 4547 participants. Anxiety prevalence ranged from 3.6% (95% CI, 0.4%-12.5%) to 58.3% (95% CI, 36.6%-77.9%). The pooled anxiety prevalence estimate from the random-effects meta-analysis was 19.1% (95% CI, 14.1%-24.6%). The level of heterogeneity in the analysis was high (I2 = 92.2%; P < .001) (Figure 2). Although visual inspection of the funnel plot asymmetry suggests the presence of publication bias, with fewer small studies reporting high anxiety prevalence, this was not found to be significant by the Egger test of bias (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Pooled Anxiety Prevalence, Grouped by Life-Limiting Condition Diagnostic Group.

Forest plot of 19 studies included in the meta-analysis of anxiety prevalence. The pooled anxiety prevalence from the meta-analysis was 19.1% (95% CI, 14.1%-24.6%). ES indicates effect size (prevalence).

Subgroup analysis revealed differences in anxiety prevalence by diagnostic group (Figure 2). Children, adolescents, and young adults with thalassemia were reported to have the highest pooled anxiety prevalence estimate (29.4% [95% CI, 8.8%-55.3%]), followed by children, adolescents, and young adults with cystic fibrosis (22.8% [95% CI, 17.1%-29.1%]). The lowest pooled anxiety prevalence estimate was found for children, adolescents, and young adults with neurological conditions (8.7% [95% CI, 4.4%-14.3%]). Pooled anxiety prevalence was also found to differ by study location; studies conducted in the United States were found to report a higher prevalence (20.8% [95% CI, 11.3%-32.1%]) than studies conducted in Europe (17.2% [95% CI, 9.9%-26.0%]). Differences in pooled anxiety prevalence were also found by assessment tool, with a lower prevalence reported from studies using self-report or parent-report questionnaires (14.9% [95% CI, 10.9%-19.4%]) compared with studies using diagnostic interviews (28.5% [95% CI, 13.2%-46.8%]). Finally, prevalence varied by the risk of bias; studies at moderate risk of bias reported a higher prevalence (23.1% [95% CI, 7.8%-43.0%]) compared with studies at low risk of bias (18.2% [95% CI, 12.8%-24.3%]) (eTable 4 in the Supplement). However, meta-regression analysis showed that only the differences by assessment tool were statistically significant (β = 0.15 [95% CI, 0.01-0.30]; P = 0.04). Prevalence was not significantly associated with sample size, mean age, or percentage of females in the sample (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

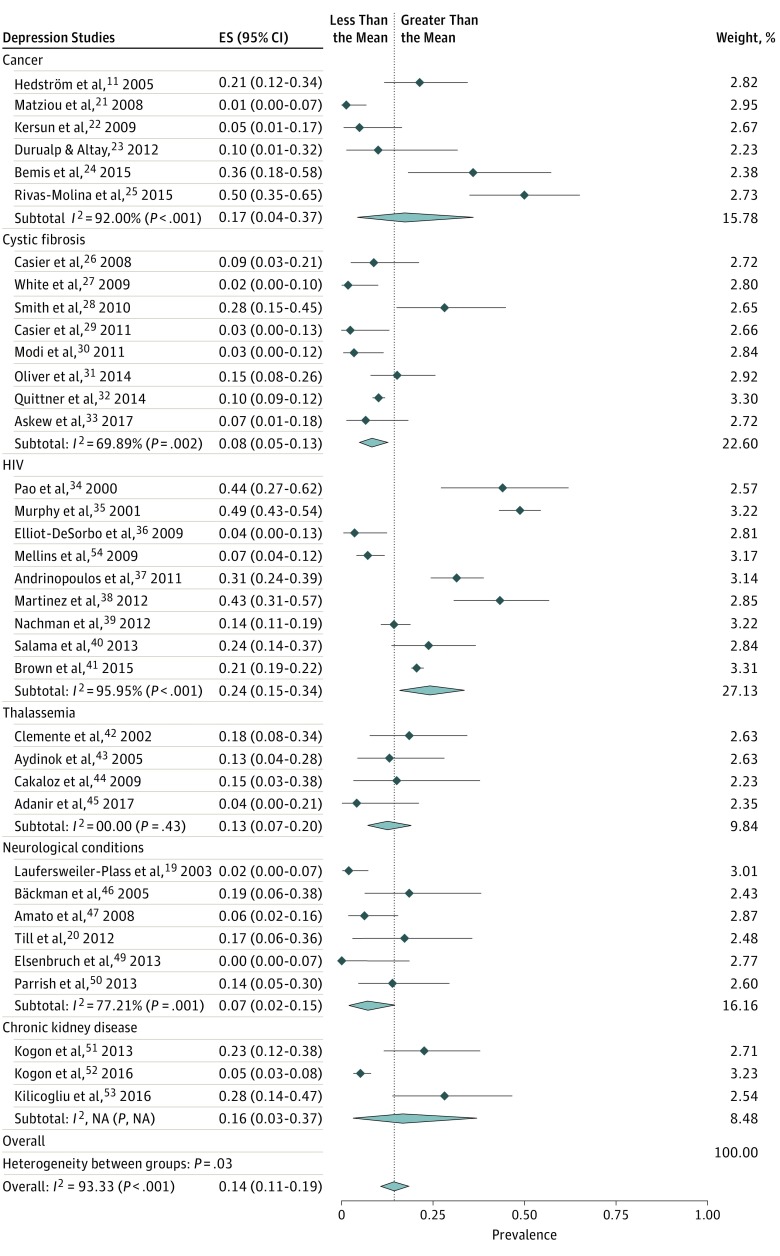

Prevalence of Depression

The prevalence of depression was reported in 36 studies,11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,52,53,54 with a total of 5934 participants. Depression prevalence ranged from 0.0% (95% CI, 0.0%-0.7%) to 50.0% (95% CI, 34.9%-65.1%). The pooled depression prevalence estimate from the random-effects meta-analysis was 14.3% (95% CI, 10.5%-18.6%). Substantial heterogeneity was found in the analysis (I2 = 93.3%; P < .001) (Figure 2). Although visual inspection of the funnel plot for the depression meta-analysis suggested some publication bias owing to a lack of published studies with large standard errors that report high depression prevalence, this was not found to be statistically significant by the Egger test of bias (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Subgroup analysis found that the pooled prevalence of depression differed by diagnostic group. Children, adolescents, and young adults with HIV reported the highest pooled depression prevalence (24.2% [95% CI, 15.4%-34.2%]), while those with neurological conditions had the lowest prevalence (7.0% [95% CI, 1.7%-15.0%]). Studies in the United States reported higher depression prevalence (18.8% [95% CI, 12.6%-25.8%]) compared with studies in Europe (9.5% [95% CI, 5.0%-15.1%]) (Figure 3). Differences in pooled depression prevalence were also found by assessment tool; studies that used self-reported or parent-reported measures had a higher pooled prevalence (15.4% [95% CI, 11.0%-20.4%]) than studies using diagnostic interviews (10.5% [95% CI, 4.0%-19.3%]). Variations in depression prevalence according to the risk of bias assigned to the study were very small; studies at moderate risk of bias reported a slightly higher prevalence (14.8% [95% CI, 6.7%-25.0%]) than studies at low risk of bias (14.2% [95% CI, 9.7%-19.4%]) (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Meta-regression analysis found only the mean age of the sample population (β = 0.02 [95% CI, 0.01-0.03]; P = .001) to be significantly associated with pooled depression prevalence (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Forest Plot of Pooled Depression Prevalence, Grouped by Life-Limiting Condition Diagnostic Group.

Forest plot of the 36 studies included in the meta-analysis of depression prevalence. The pooled depression prevalence from the meta-analysis was 14.3% (95% CI, 10.5%-18.6%). ES indicates effect size (prevalence).

Discussion

Key Findings

When compared with available data from the general population, this meta-analysis of 37 studies indicates a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs compared with the general population. The pooled anxiety prevalence estimate of 19.1% observed in this analysis is more than 6 times higher than the prevalence of anxiety among the general population of young people in the United States, 3%, and more than double the anxiety prevalence of children and young people in the United Kingdom, 7.2%.2,55 The observed prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs was 14.3%, which was also higher than the range of depression prevalence estimates found for young people in the United States and the United Kingdom (2.1%-8.1%).2,55

Interestingly, the prevalence of anxiety and depression was found to vary by LLC diagnostic group. The highest pooled anxiety prevalence estimate (29.4%) was found for children, adolescents, and young adults with thalassemia, whereas those with HIV reported the highest pooled prevalence of depression (24.2%). Overall, these findings support the literature describing the challenges of living with a LLC and highlight the fact that recognition of and provision for psychological needs should be a core aspect of the care and support offered to this population.8,56

It was also observed that anxiety and depression prevalence estimates were modified by the type of assessment tool used, with diagnostic interviews resulting in higher anxiety prevalence. Differences in anxiety prevalence by the type of assessment tool used have been shown in previous studies—for example, a systematic review of anxiety prevalence in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders.57 Conversely, higher depression prevalence was associated with the use of self-report or parent-report questionnaires, a finding previously reported by a systematic review of the prevalence of depression among adults with chronic kidney disease.58 These findings may be partially accounted for by the diagnostic groups studied. For example, more than half of the studies using diagnostic interviews concerned children, adolescents, and young adults with thalassemia, and the pooled anxiety prevalence for this group was very high, whereas in the case of depression, the highest pooled prevalence was found for HIV studies, most of which used self-reported or parent-reported measures.

Finally, age was identified by the meta-regression analysis to be significantly associated with depression prevalence. This trend is consistent to that found among young people with anxiety or depression both in the United States and the United Kingdom.2,55 Although sex was not found to be associated with depression prevalence, and neither sex nor age were associated with anxiety prevalence, these findings should be treated with particular caution, given that many studies could not be included in the meta-regression model owing to lack of reporting of age and sex data.

Strengths

This review has a number of strengths. First, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of anxiety and depression prevalence among children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs to have been conducted. Given that there are increasing numbers of children, adolescents, and young adults living with LLCs, and recent calls have been made to recognize and address the mental health needs of this population, a comprehensive picture of existing evidence of the prevalence of depression and anxiety across this population is extremely valuable. Second, the comprehensive search strategy used in this review resulted in the inclusion of a total of 37 studies in the meta-analyses from more than 10 countries covering 5 LLC diagnostic groups. This improves the robustness of the pooled prevalence estimates, offering a more accurate description of the epidemiology of anxiety and depression in this patient group than is afforded by single studies.

Limitations

However, weaknesses in the review methodology must be noted. First, only studies written in English were eligible for inclusion, limiting the generalizability of the prevalence estimates. This review is also limited by the available data set. As such, the coverage of LLCs is far from exhaustive. Importantly, of the 6042 participants included in the review, only 342 (5.7%) had neurological conditions, yet more than 8% of children and adolescents with a LLC in England have a neurological diagnosis.14 Importantly, intellectual disability, which brings an increased risk of mental health problems, is a common comorbidity among this group.59 However, the identification of mental health problems or emotional distress in young people with intellectual disability can be complex owing to communication limitations.60 While greater efforts should be made to improve accessibility and suitability of self-reported or parent-reported measures, for some individuals, the detection of emotional distress will rely on methods such as the interpretation of nonverbal behaviors, utterances, and physiological responses.60

There are also some broader limitations in terms of the characteristics of the included studies. First, many studies had very small sample sizes. When combined with the relatively narrow range of LLCs represented, this limits the ability of any analysis to produce results that are representative of the population. Additionally, this makes it more difficult to compare results with general population data. Second, there was poor reporting of key study data, such as the age and sex of study participants. For example, only 15 of the included studies (79%) reporting anxiety prevalence and 24 of the studies (67%) reporting depression prevalence provided the mean age of the sample. This greatly reduced the number of studies that could be included in the meta-regression models. Finally, because no studies reported longitudinal data, the incidence of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs could not be assessed.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the findings have a number of key implications. Importantly, they support the argument for routine screening for mental health problems as part of the development of psychosocial standards of care.61 This would both assist the systematic identification of patients at risk of mental health problems and the instigation of preventive steps and identify those needing support and treatment. Data from routine screening would also be valuable evidence for those making the case for increasing the resources available for mental health and psychosocial care provision within their services.

There has already been some progress on this issue. For example, annual screening for mental health problems in patients with cystic fibrosis was recommended in the European consensus on standards of care.62 However, for this to be performed effectively, screening tools must first be validated in children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs, because currently most of the anxiety and depression measurement tools have only been validated in the general population.63

In addition to work on the psychometric properties of screening instruments, 2 further areas of research are required. First, more large-scale studies are needed, including on a broader range of LLCs, to consolidate existing evidence and further understand differences in the prevalence of mental health problems between different LLCs. For the effects of age and sex to be adequately assessed in future studies, results should be reported by sex and age group. Second, longitudinal studies are required to develop the understanding of the temporal associations between the diagnosis of a LLC, its trajectory, and the onset of mental health problems, while also allowing for an exploration of factors which increase the risk of anxiety or depression onset.

Anxiety and depression are common mental health problems among children, adolescents, and young adults with LLCs, calling for the implementation of routine screening to identify both those at risk of mental health problems and those requiring treatment. However, to further understand the epidemiology of anxiety and depression in this patient population, larger longitudinal studies must be conducted in a wider range of LLCs, including on children with neurological conditions and cognitive impairment.

eTable 1. Medline Search Strategy

eTable 2. Risk of Bias Assessment

eTable 3. Anxiety & Depression Assessment Tools

eTable 4. Sub-group analysis of pooled anxiety prevalence

eTable 5. Meta-regression analysis of pooled anxiety prevalence

eTable 6. Sub-group analysis of pooled depression prevalence

eTable 7. Meta-regression analysis of pooled depression prevalence

eFigure 1. Funnel plot for anxiety meta-analysis, with pseudo 95% confidence limits

eFigure 2. Funnel plot for depression meta-analysis, with pseudo 95% confidence limits

References

- 1.Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515-1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005-2011. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(2):1-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [published correction appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):768]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(9):1003-1016. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic physical illnesses: a meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(8):1069-1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(4):375-384. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Together for Short Lives Children’s palliative care definitions. https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/get-support/supporting-you/family-resources/childrens-palliative-care-definitions/. Published 2017. Accessed December 30, 2017.

- 8.Barlow JH, Ellard DR. The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: an overview of the research evidence base. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32(1):19-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00591.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christie D, Viner R. Adolescent development. BMJ. 2005;330(7486):301-304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadeau L, Tessier R. Social adjustment of children with cerebral palsy in mainstream classes: peer perception. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(5):331-336. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedström M, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Perceptions of distress among adolescents recently diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(1):15-22. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000151803.72219.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celano CM, Freudenreich O, Fernandez-Robles C, Stern TA, Caro MA, Huffman JC. Depressogenic effects of medications: a review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):109-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higham L, Ahmed S, Ahmed M. Hoping to live a “normal” life whilst living with unpredictable health and fear of death: impact of cystic fibrosis on young adults. J Genet Couns. 2013;22(3):374-383. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9555-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e923-e929. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) End of life care for infants, children and young people with life-limiting conditions: planning and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng61/chapter/recommendations. Published 2016. Accessed December 11, 2017. [PubMed]

- 16.Fraser LK, Jarvis SW, Moran NE, Aldridge J, Parslow RC, Beresford BA Children in Scotland requiring palliative care: identifying numbers and needs (the CHISP study). https://www.york.ac.uk/media/spru/projectfiles/ProjectOutput_ChispReport.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 17.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934-939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974-978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laufersweiler-Plass C, Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Zerres K, Backes M, Lehmkuhl G, von Gontard A. Behavioural problems in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy and their siblings. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45(1):44-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2003.tb00858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Till C, Udler E, Ghassemi R, Narayanan S, Arnold DL, Banwell BL. Factors associated with emotional and behavioral outcomes in adolescents with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18(8):1170-1180. doi: 10.1177/1352458511433918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matziou V, Perdikaris P, Galanis P, Dousis E, Tzoumakas K. Evaluating depression in a sample of children and adolescents with cancer in Greece. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;55(3):314-319. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kersun LS, Rourke MT, Mickley M, Kazak AE. Screening for depression and anxiety in adolescent cancer patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(11):835-839. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181b8704c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durualp E, Altay N. A comparison of emotional indicators and depressive symptom levels of school-age children with and without cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29(4):232-239. doi: 10.1177/1043454212446616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bemis H, Yarboi J, Gerhardt CA, et al. Childhood cancer in context: sociodemographic factors, stress, and psychological distress among mothers and children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(8):733-743. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivas-Molina NS, Mireles-Pérez EO, Soto-Padilla JM, González-Reyes NA, Barajas-Serrano TL, Barrera de León JC. Depresión en escolares y adolescentes portadores de leucemia aguda en fase de tratamiento. Gac Med Mex. 2015;151(2):186-191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casier A, Goubert L, Huse D, et al. The role of acceptance in psychological functioning in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: a preliminary study. Psychol Health. 2008;23(5):629-638. doi: 10.1080/08870440802040269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White T, Miller J, Smith GL, McMahon WM. Adherence and psychopathology in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(2):96-104. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0709-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith BA, Modi AC, Quittner AL, Wood BL. Depressive symptoms in children with cystic fibrosis and parents and its effects on adherence to airway clearance. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(8):756-763. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casier A, Goubert L, Theunis M, et al. Acceptance and well-being in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis: a prospective study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(4):476-487. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modi AC, Driscoll KA, Montag-Leifling K, Acton JD. Screening for symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46(2):153-159. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliver KN, Free ML, Bok C, McCoy KS, Lemanek KL, Emery CF. Stigma and optimism in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(6):737-744. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quittner AL, Goldbeck L, Abbott J, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: results of the International Depression Epidemiological Study across nine countries. Thorax. 2014;69(12):1090-1097. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Askew K, Bamford J, Hudson N, et al. Current characteristics, challenges and coping strategies of young people with cystic fibrosis as they transition to adulthood. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(2):121-125. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-2-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pao M, Lyon M, D’Angelo LJ, Schuman WB, Tipnis T, Mrazek DA. Psychiatric diagnoses in adolescents seropositive for the human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(3):240-244. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy DA, Durako SJ, Moscicki AB, et al. ; Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network . No change in health risk behaviors over time among HIV infected adolescents in care: role of psychological distress. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3)(Suppl):57-63. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00287-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elliott-DeSorbo DK, Martin S, Wolters PL. Stressful life events and their relationship to psychological and medical functioning in children and adolescents with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(3):364-370. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b73568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrinopoulos K, Clum G, Murphy DA, et al. ; Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions . Health related quality of life and psychosocial correlates among HIV-infected adolescent and young adult women in the US. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(4):367-381. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez J, Harper G, Carleton RA, et al. ; Adolescent Medicine Trials Network . The impact of stigma on medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescent and young adult females and the moderating effects of coping and satisfaction with health care [published correction appears in AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(10):565]. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(2):108-115. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nachman S, Chernoff M, Williams P, Hodge J, Heston J, Gadow KD. Human immunodeficiency virus disease severity, psychiatric symptoms, and functional outcomes in perinatally infected youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):528-535. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salama C, Morris M, Armistead L, et al. Depressive and conduct disorder symptoms in youth living with HIV: the independent and interactive roles of coping and neuropsychological functioning. AIDS Care. 2013;25(2):160-168. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown LK, Whiteley L, Harper GW, Nichols S, Nieves A; ATN 086 Protocol Team for The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions . Psychological symptoms among 2032 youth living with HIV: a multisite study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(4):212-219. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clemente C, Tsiantis J, Sadowski H, et al. Psychopathology in children from families with blood disorders: a cross-national study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11(4):151-161. doi: 10.1007/s00787-002-0257-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aydinok Y, Erermis S, Bukusoglu N, Yilmaz D, Solak U. Psychosocial implications of thalassemia major. Pediatr Int. 2005;47(1):84-89. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.02009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cakaloz B, Cakaloz I, Polat A, Inan M, Oguzhanoglu NK. Psychopathology in thalassemia major. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(6):825-828. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02865.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adanır AS, Taskıran G, Fettahoglu EC, Ozatalay E. Psychopathology and family functioning in adolescents with beta thalassemia. Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):4-12. doi: 10.2174/2210676606666161115143217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bäckman ML, Santavuori PR, Aberg LE, Aronen ET. Psychiatric symptoms of children and adolescents with juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49(pt 1):25-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amato MP, Goretti B, Ghezzi A, et al. ; Multiple Sclerosis Study Group of the Italian Neurological Society . Cognitive and psychosocial features of childhood and juvenile MS. Neurology. 2008;70(20):1891-1897. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312276.23177.fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amato MP, Goretti B, Ghezzi A, et al. ; Multiple Sclerosis Study Group of the Italian Neurological Society . Cognitive and psychosocial features in childhood and juvenile MS: two-year follow-up. Neurology. 2010;75(13):1134-1140. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elsenbruch S, Schmid J, Lutz S, Geers B, Schara U. Self-reported quality of life and depressive symptoms in children, adolescents, and adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a cross-sectional survey study. Neuropediatrics. 2013;44(5):257-264. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1347935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parrish JB, Weinstock-Guttman B, Smerbeck A, Benedict RH, Yeh EA. Fatigue and depression in children with demyelinating disorders. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(6):713-718. doi: 10.1177/0883073812450750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kogon AJ, Vander Stoep A, Weiss NS, Smith J, Flynn JT, McCauley E. Depression and its associated factors in pediatric chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(9):1855-1861. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2497-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kogon AJ, Matheson MB, Flynn JT, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) Study Group; Chronic Kidney Disease in Children CKiD Study Group . Depressive symptoms in children with chronic kidney disease. J Pediatr. 2016;168:164-170. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kilicoglu AG, Bahali K, Canpolat N, et al. Impact of end-stage renal disease on psychological status and quality of life. Pediatr Int. 2016;58(12):1316-1321. doi: 10.1111/ped.13026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu C-S, et al. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1131-1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vizard T, Pearce N, Davis J, et al. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017: emotional disorders. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017. Published 2018. Accessed March 8, 2019.

- 56.Ferro MA, Boyle MH. The impact of chronic physical illness, maternal depressive symptoms, family functioning, and self-esteem on symptoms of anxiety and depression in children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43(1):177-187. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9893-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Steensel FJA, Bögels SM, Perrin S. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(3):302-317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84(1):179-191. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Einfeld SL, Ellis LA, Emerson E. Comorbidity of intellectual disability and mental disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;36(2):137-143. doi: 10.1080/13668250.2011.572548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vos P, De Cock P, Munde V, Petry K, Van Den Noortgate W, Maes B. The tell-tale: what do heart rate; skin temperature and skin conductance reveal about emotions of people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities? Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(4):1117-1127. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: an introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(suppl 5):S419-S424. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kerem E, Conway S, Elborn S, Heijerman H; Consensus Committee . Standards of care for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4(1):7-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thabrew H, McDowell H, Given K, Murrell K. Systematic review of screening instruments for psychosocial problems in children and adolescents with long-term physical conditions. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017;4:X17690314. doi: 10.1177/2333794X17690314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Medline Search Strategy

eTable 2. Risk of Bias Assessment

eTable 3. Anxiety & Depression Assessment Tools

eTable 4. Sub-group analysis of pooled anxiety prevalence

eTable 5. Meta-regression analysis of pooled anxiety prevalence

eTable 6. Sub-group analysis of pooled depression prevalence

eTable 7. Meta-regression analysis of pooled depression prevalence

eFigure 1. Funnel plot for anxiety meta-analysis, with pseudo 95% confidence limits

eFigure 2. Funnel plot for depression meta-analysis, with pseudo 95% confidence limits