Abstract

This economic evaluation examines whether pharmaceutical industry payments to gastroenterologists are associated with how often they prescribe the pharmaceuticals’ drugs for inflammatory bowel disease.

Biologic medications account for the majority of outpatient treatment expenditures for inflammatory bowel disease.1 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie Inc) for Crohn disease (CD) in 2007 and ulcerative colitis (UC) in 2012 and approved certolizumab (Cimzia, Union Chimique Belge) for CD in 2006.

For Medicare beneficiaries, adalimumab and certolizumab are the biologic agents prescribed by the largest number of gastroenterologists. These gastroenterologists frequently receive payments from the manufacturers of high-revenue medications.2,3 We investigated the association between payments from the manufacturers of these drugs to gastroenterologists and Medicare spending on these drugs.

Methods

We linked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Part D Prescriber Database4 and the CMS Open Payments Database5 from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016. Data were analyzed from June 5, 2018, to February 21, 2019.

We included the biologic medications with FDA approval for CD or UC that were prescribed by more than 100 gastroenterologists to Medicare beneficiaries from 2014 to 2016. We included only gastroenterologists based on clinician type as listed by CMS. Among the approximately 14 000 active US-based gastroenterologists, those with more than 11 filled prescriptions per year for at least 1 of these biologic medications were included.

Payments were considered to be relevant if a gastroenterologist received them from a drug manufacturer in the year that the medication was prescribed. Thus, we considered a payment from AbbVie as relevant if it was made in 2014 to a gastroenterologist prescribing adalimumab in 2014. We classified payments as: (1) for education; (2) for food, travel, and lodging expenses; and (3) for speaking and consulting.5 Research payments were excluded. The St Michael’s Hospital Ethics Board exempted this study from ethics review.

In a linear regression, we used the dollar value of payments from drug manufacturers to physicians as the exposure, and Medicare spending on biologic prescriptions as the outcome. We repeated the analysis for (1) physicians receiving less than $5000 over the 3 years; (2) physicians with more than 100 prescriptions over the 3 years; and (3) each payment type separately.

Results

From 2014 to 2016, the Open Payments database included $10 906 177 in payments to gastroenterologists prescribing adalimumab or certolizumab. For adalimumab, payments were $13 034 for education, $4 953 998 for food, travel, and lodging expenses, and $5 580 947 for speaking and consulting. For certolizumab, payments were $60 369, $117 554, and $180 285, respectively (Table). There were 3737 prescribing gastroenterologists and $621 091 139 in Medicare expenditures for adalimumab, and 621 gastroenterologists and $55 883 266 in Medicare expenditures for certolizumab.

Table. Industry Payment Classifications for Adalimumab and Certolizumab.

| Payment Type | Prescribers, No. (%) | Payment, $ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Value | Median (IQR) | ||

| Adalimumab (3737 Total Prescribing Gastroenterologists; $621 091 139 in Associated Medicare Spending)a,b | |||

| Total | 2822 (76) | 10 547 978 | 183 (28-517) |

| Education | 332 (9) | 13 034 | 0 |

| Food, travel, and lodging | 2813 (75) | 4 953 998 | 154 (11-459) |

| Speaking and consulting | 240 (6) | 5 580 947 | 0 |

| Certolizumab (621 Total Prescribing Gastroenterologists; $55 883 266 in Associated Medicare Spending)b,c | |||

| Total | 332 (53) | 358 199 | 25 (0-90) |

| Education | 13 (2) | 60 369 | 0 |

| Food, travel, and lodging | 327 (53) | 117 544 | 13 (0-69) |

| Speaking and consulting | 30 (5) | 180 285 | 0 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Reported percentages are of total number of gastroenterologists who prescribed adalimumab from 2014 to 2016.

Medicare expenditure for filling prescriptions of adalimumab and certolizumab prescribed by gastroenterologists from 2014 to 2016.

Reported percentages are of total number of gastroenterologists who prescribed certolizumab from 2014 to 2016.

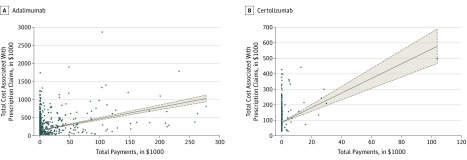

We found a significant association between industry payments and Medicare spending (Figure). For every $1 in payments, there was a $3.16 increase in spending for adalimumab (95% CI, $2.84-$3.48; P < .001), and a $4.72 increase for certolizumab (95% CI, $3.65-$5.80; P < .001). Additional analyses showed similar trends when restricted to gastroenterologists receiving less than $5000 for adalimumab (n = 3532) and certolizumab (n = 607) and with more than 100 prescriptions for adalimumab (n = 233) (data not shown). Because only 3 gastroenterologists had more than 100 prescriptions for certolizumab, their data were not analyzed.

Figure. Associations of Industry Payments With Prescriptions for Biologic Medications.

Total payments received by each physician are plotted on the horizontal axis, while total cost associated with prescriptions written by each physician is plotted on the vertical axis. A, Association of industry payments with prescription numbers for 3737 physicians prescribing adalimumab. B, Association of industry payments with prescription numbers for 621 physicians prescribing certolizumab.

We found that every $1 in education payments was associated with a $232.65 increase (95% CI, $88.41-$376.88; P = .002) in Medicare spending for adalimumab and a $5.83 increase in spending for certolizumab, which was not significant (95% CI, −$19.26 to $30.91; P = .62). For food, travel, and lodging payments, every $1 was associated with a $6.13 increase (95% CI; $5.40-$6.86; P < .001) in spending for adalimumab and an increase of $10.48 (95% CI, $7.53-$13.43; P < .001) for certolizumab. For consulting and speaking payments, every $1 was associated with a $3.55 increase (95% CI, $2.14-$4.97; P < .001) in spending for adalimumab and a $6.82 increase (95% CI, $3.36-$10.28; P < .001) for certolizumab.

Limitations include potential errors in CMS data6 and lack of adjustment for confounders, such as age and practice location. Additionally, our data indicate an association and not causation.

Conclusions

From 2014 to 2016, we found an association between payments from the manufacturers of adalimumab and certolizumab to gastroenterologists and Medicare spending on these drugs. These findings persisted with smaller payments, higher-volume prescribers, and different payment types.

References

- 1.Yu H, MacIsaac D, Wong JJ, et al. Market share and costs of biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel disease in the USA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(3):364-370. doi: 10.1111/apt.14430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan R, Scaffidi MA, Rumman A, Grindal AW, Plener IS, Grover SC. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among authors of clinical guidelines related to high-revenue medications. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1712-1715. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the Open Payments program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(1):84-96. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data Part D Prescriber. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Part-D-Prescriber.html. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- 5.Open Payments Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2015. https://www.cms.gov/openpayments/. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- 6.Santhakumar S, Adashi EY. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act: testing the value of transparency. JAMA. 2015;313(1):23-24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]