Abstract

This cross-sectional study uses Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data to evaluate the association between industry payments to physicians who prescribe gabapentinoids and gabapentinoid prescribing behavior.

Gabapentin and pregabalin are γ-aminobutyric acid analogues.1 Gabapentin (Neurontin; Pfizer) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1993 for seizure disorders and postherpetic neuralgia; it became available as a generic in 2004. Two extended-release versions are marketed as brand-name products: Gralise (Assertio Therapeutics) and Horizant (Arbor Pharmaceuticals). Pregabalin (Lyrica; Pfizer) was approved in 2004 for seizure disorders, postherpetic neuralgia, neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia; a generic formulation is not available. Patient use of gabapentinoids has increased from 1.2% of US adults in 2002 to 3.9% in 2015,2 raising concerns about appropriate use.3 We examined associations between industry payments to physicians associated with gabapentinoids and physicians’ prescribing.

Methods

We used Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2014 to 2016 Part D prescribing data linked to 2014 to 2016 Open Payments data.4,5 With Open Payments data, we identified general payments from industry to physicians associated with gabapentinoids, all of which were for the 3 brand-name products. We excluded research payments and payments associated with ownership and licensing fees because they are less likely to be associated with drug promotion. With Part D Prescriber data, we identified all gabapentinoid prescriptions. We linked the data sets at the physician level and categorized physicians as generalists (family medicine, general practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology), pain medication specialists (anesthesiology, neuromusculoskeletal medicine, pain medicine, psychiatry and neurology, and pain-related physical medicine and rehabilitation), or other.

We estimated physician prescribing as the physician's proportion of prescription days filled for the 3 brand-name gabapentinoids in aggregate of all gabapentinoid prescription days filled. To account for the distribution of the data, we used Poisson regression models to examine the association between industry payments and physician prescribing. We conducted subgroup analyses by physician specialty and payment type, which were categorized as (1) food and beverages, gifts, and educational materials, or (2) speaker fees, consulting fees, honoraria, travel and lodging, or non-research grants. All analyses were conducted with Stata, version 15.1 MP/6-Core (StataCorp) and ArcMap, version 10.4.1. (Esri), and statistical significance was set as 2-sided P < .05. Because this study used publicly available data, the Yale University School of Medicine institutional review board exempted the study from review.

Results

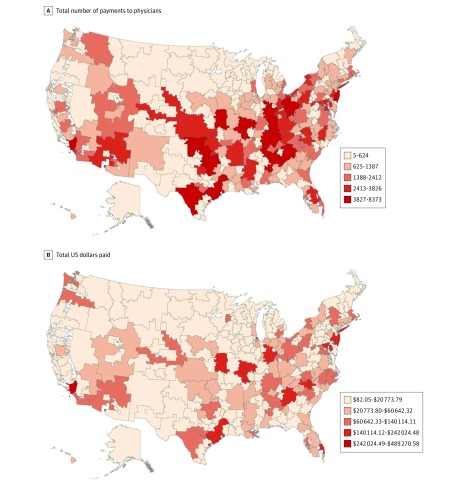

Between 2014 and 2016, the manufacturers of the 3 brand-name gabapentinoids made 509 874 general payments ($11.5 million) to 51 005 physicians; these physicians represented 14.4% of physicians who prescribed any gabapentinoid product under Part D during these years. The payments were most commonly made to physicians in the southern and eastern regions of the United States (Figure). Generalist physicians received 316 372 (62.0%) payments ($3.7 million), pain medication specialists 148 119 (29.1%) payments ($6.6 million), and other physicians 45 383 (8.9%) payments ($1.2 million). Of the payments, 486 322 (95.4%) were for food and beverages, gifts, or educational materials ($5.3 million) (Table).

Figure. Geographic Variation of Industry Payments for Gabapentinoids From 2014 to 2016.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments data, 2014-2016.4

Table. Industry Payments to Physicians and Prescribing of Brand-Name Gabapentinoids, 2014-2016.

| Variable | Payments Associated With Brand-Name Gabapentinoidsa | Likelihood of Prescribing Brand-Name Gabapentinoids | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.(%) | Total Amount $, (%) | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| General payments | 509 874 (100) | 11 453 810.87 (100) | 1.91 (1.87-1.96) | <.001 |

| Payment by physician typeb | ||||

| Generalists | 316 372 (62.0) | 3 733 357.02 (32.6) | 1.70 (1.64-1.76) | <.001 |

| Pain medication specialists | 148 119 (29.1) | 6 564 296.51 (57.3) | 2.76 (2.60-2.92) | <.001 |

| Other | 45 383 (8.9) | 1 156 157.34 (10.1) | 2.41 (2.27-2.56) | <.001 |

| Payment type | ||||

| Food and beverages, gifts, or educational materials | 486 322 (95.4) | 5 312 708.99 (46.4) | 1.91 (1.87-1.96) | <.001 |

| Speaker fees, consulting fees, honoraria, travel costs, or non-research grants | 23 552 (4.6) | 6 150 192.22 (53.7) | 1.30 (1.25-1.36) | <.001 |

Lyrica (pregabalin; Pfizer), Gralise (gabapentin; Assertio Therapeutics), and Horizant (gabapentin; Arbor Pharmaceuticals).

Types are categorized as generalists (family medicine, general practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology), pain medication specialists (anesthesiology, neuromusculoskeletal medicine, pain medicine, psychiatry and neurology, and pain-related physical medicine and rehabilitation), and other.

Among physicians who prescribed any gabapentinoid, generic gabapentin (87.4%) and pregabalin (Lyrica, 12.4%) were most commonly prescribed. Physicians receiving payments from industry were more likely to prescribe the 3 brand-name gabapentinoids than generic gabapentin (incidence rate ratio, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.87-1.96; P < .001). Incidence rate ratios consistently demonstrated that physicians receiving payments from industry were more likely to prescribe brand-name gabapentinoids (ranging from 1.30 for pain medication specialists; 95% CI, 1.25-1.36; P < .001, to 2.76 for speaker fee payment type; 95% CI, 2.60-2.92; P < .001) (Table).

Discussion

Among physicians who prescribed gabapentinoids, receipt of payments from industry was associated with a higher likelihood of prescribing brand-name products than generic gabapentin. Such prescribing increases spending for Medicare and beneficiaries because brand-name gabapentinoids typically cost several hundred dollars for a 1-month supply and accounted for nearly $2500 in mean Medicare spending per beneficiary in 2016 compared with less than $20 for a 1-month supply of gabapentin, or $89 in mean Medicare spending per beneficiary.6

Limitations of this study should be noted. The study was cross-sectional and thus cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship between payment and prescribing. Also, we did not assess other potential factors in prescribing patterns, such as direct-to-consumer advertising, or prescription appropriateness. Nonetheless, our findings raise concerns about the reasons some physicians prescribe brand-name gabapentinoids and not less-expensive generic alternatives.

References

- 1.Wallach JD, Ross JS. Gabapentin Approvals, Off-Label Use, and Lessons for Postmarketing Evaluation Efforts. JAMA. 2018;319(8):776-778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansen ME. Gabapentinoid Use in the United States 2002 Through 2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):292-294. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR. Abuse and Misuse of Pregabalin and Gabapentin. Drugs. 2017;77(4):403-426. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0700-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open payments. https://www.cms.gov/openpayments/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Part D Prescriber. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Part-D-Prescriber.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medicare Part D Drug Spending Dashboard. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD.html. Accessed March 13, 2019.