Abstract

Introduction

Our aim was to investigate the accuracy of postmortem fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compared with fetal autopsy in second trimester pregnancies terminated due to fetal anomalies. A secondary aim was to compare the MRI evaluations of two senior radiologists.

Material and methods

This was a prospective study including 34 fetuses from pregnancies terminated in the second trimester due to fetal anomalies. All women accepted a postmortem MRI and an autopsy of the fetus. Two senior radiologists performed independent evaluations of the MRI images. A senior pathologist performed the fetal autopsies. The degree of concordance between the MRI evaluations and the autopsy reports was estimated as well as the consensus between the radiologists.

Results

Thirty‐four fetuses were evaluated. Sixteen cases were associated with the central nervous system (CNS), five were musculoskeletal, one cardiovascular, one was associated with the urinary tract, and 11 cases had miscellaneous anomalies such as chromosomal aberrations, infections and syndromes. In the 16 cases related to the CNS, both radiologists reported all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in 15 (94%; CI 70%‐100%) cases. In the 18 non‐CNS cases, both radiologists reported all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in six (33%; CI 5%‐85%) cases. In 21 cases (62%; CI 44%‐78%), both radiologists held opinions that were consistent with the autopsy reports. The degree of agreement between the radiologists was high, with a Cohen's Kappa of 0.87.

Conclusions

Postmortem fetal MRI can replace autopsy for second trimester fetuses with CNS anomalies. For non‐CNS anomalies, the concordance is lower but postmortem MRI can still be of value when autopsy is not an option.

Keywords: fetal anomalies, fetal diagnosis, postmortem fetal MRI, prenatal diagnosis, prospective study, second trimester

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

Key message.

Postmortem fetal magnetic resonance imaging can replace conventional autopsy for second trimester fetuses with central nervous system anomalies.

1. INTRODUCTION

In Sweden, all pregnant women are offered a fetal ultrasound examination around gestational week 18.1 Severe fetal anomalies can be detected during this examination and subsequently lead to a termination of the pregnancy.

Thereafter, an autopsy of the fetus is recommended to verify the diagnosis and reveal other anomalies of importance when counseling the couple concerning forthcoming pregnancies, including the risk of recurrence. Moreover, the autopsy can serve as a quality control of the prenatal ultrasound.2

This recommendation, however, is not always in line with the wishes of the pregnant woman and her partner. Despite the increase in pregnancy terminations, a reduction in fetal autopsies has been recognized in the last few decades. A main reason is that couples decline fetal autopsies.3, 4

Therefore, non‐invasive postmortem fetal investigations using ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and minimal invasive endoscopy or biopsy have been suggested as replacements or complements to the conventional autopsy.5, 6, 7

However, postmortem MRI is still not implemented in routine clinical work due to limited knowledge.6 Existing reports are often small and concern a mixture of cases including infants, stillbirths, as well as fetuses from spontaneous abortions and terminated pregnancies, often with non‐specific gestational ages. Many are also specified to the central nervous system (CNS), and often only one radiologist analyzed the MRI images.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 The largest study published comprises 185 fetuses from the second trimester.12 That study, however, contains a mixture of fetuses from spontaneous and induced abortions, and early pregnancy cases are defined as at or below 24 weeks.

Our aim was to investigate the accuracy of postmortem fetal MRI compared with fetal autopsy as gold standard in second trimester pregnancies terminated due to fetal anomalies.

A secondary aim was to compare the MRI evaluations of two senior radiologists.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Women who came to the Fetal Medicine unit at Uppsala University hospital for termination of pregnancy in the second trimester due to fetal anomalies, were informed verbally about the study and asked if they would be willing to participate. All anomalies were diagnosed by ultrasound and assessed as either not being compatible with life or leading to serious morbidity. In 10 cases, the prenatal diagnosis was confirmed by MRI. Gestational age was estimated by ultrasound or in a few cases by last menstrual period. A prerequisite for participation was that the woman accepted both an autopsy and a postmortem MRI of the fetus.

All participants were prospectively recruited between 2006 and 2013 and signed an informed consent. Non‐participants were not registered. Most MRI examinations were performed outside of office hours in order not to disturb the clinical routines. We decided arbitrarily to include at least 30 cases that we thought would result in a diversity of anomalies and not risk making the data collection period too unwieldly.

All fetuses were kept in a refrigerator from termination of pregnancy to time of autopsy.

A senior pathologist at the Department of Pathology at Uppsala University hospital performed the fetal autopsies. MRI examinations were performed at Uppsala University Hospital on a 1.5 T scanner (first Gyroscan ACS Intera, later upgraded to Gyroscan Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) using a knee coil. T2‐weighted images were acquired in the three main planes of the fetus (sagittal, coronal and axial) using a turbo spin echo sequence with a repetition time of 1586 ms, echo time 100 ms, slice thickness 2 mm and in‐plane resolution 0.6 × 0.6 mm. In addition, a 3D T1‐weighted magnetization prepared gradient echo sequence was performed in the sagittal plane, with a repetition time of 12 ms, echo time 6 ms, flip angle 8 degrees, slice thickness 1 mm and in‐plane resolution of 0.6 × 0.9 mm. Axial and coronal images were also reconstructed from this sequence. The total examination time was approximately 1 hour. Two senior radiologists, subspecialists in neuroradiology and pediatric radiology, respectively, evaluated the MRI images independently. The radiologists and the pathologist were aware of the prenatal ultrasound findings but were blinded to each other's reports.

The findings of the fetal autopsy reports were compared with the MRI evaluations and classified in consensus between four of the authors (A.H, A.M.L, J.W. and O.A.).

The cases were allocated into four categories:

All major anomalies detected by MRI.

Some major anomalies detected by MRI, including the most clinically significant.

Some major anomalies detected by MRI, but not the most clinically significant.

None of the major anomalies detected by MRI.

A major anomaly was defined as an anomaly that could have led to fetal or infant death or resulted in severe morbidity of an infant.8 The reports from the radiologists were compared regarding the unanimity in the categorization. Changes normally observed in postmortem MRI examinations were not regarded as pathological findings. This included fluid accumulations in the pleura, pericardial sac and peritoneum; gas accumulations; minimal amounts of intraventricular blood; head molding; skin maceration.13

2.1. Statistical analyses

The method described by Clopper and Pearson14 was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the percentages in the result section. The degree of agreement between the radiologists was estimated by Cohen's Kappa.

2.2. Ethical approval

The regional ethics committee in Uppsala approved the study (dnr 2005:194, 31 October 2005).

3. RESULTS

All MRI images were of such quality that an evaluation was possible. The gestational ages, at termination of pregnancy, varied from 15 weeks 4 days to 22 weeks 5 days (Tables 1 and 2). The median was 18 weeks 3 days.

Table 1.

CNS cases. Diagnoses according to fetal autopsy and MRI reports by two senior radiologists including a comparison, gestational age at termination of pregnancy and days between termination and postmortem MRI and autopsy

| Case number | Diagnosis according to fetal autopsy | Most clinically significant major anomaly | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 1 | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 2 | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 1 vs fetal autopsyc | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 2 vs fetal autopsyc | Gestational age at termination of pregnancy (d) | Days from termination of pregnancy to MRI (d) | Days from termination of pregnancy to autopsy (d) | Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Schizencephalya | Schizencephaly Bowel atresia |

Schizencephaly | Schizencephaly | 1 | 1 | 22+5 | 0 | 3 | Hydrocephalus |

| 2 | Hydrocephalus Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Hydrocephalus Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Closure defect at lumbosacral spine Moderate widening of the ventricles supratentorially Cerebellar herniation |

1 | 1 | 18+1 | 0 | 3 | Myelomeningocele |

| 6 | Malignant teratoma | Malignant teratoma | Multicystic orbitotemporal tumor Exophthalmus |

Temporal tumor with mixed cystic and solid parts Dislocation of adjacent brain and orbit |

1 | 1 | 20+3 | 1 | 2 | Intracranial process |

| 7 | Cerebellar herniation Skull base defect Lumbar myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Hydrocephalus Myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Hydrocephalus Closure defect lumbar spine |

1 | 1 | 17+2 | 0 | 5 | Myelomeningocele |

| 10 | Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Corpus callosum agenesis Lumbar myelomeningocele |

Cerebellar herniation Closure defect lumbar spine |

1 | 1 | 15+4 | 0 | 2 | Myelomeningocele |

| 13 | Cortical migration disturbanceb

Cyst in the posterior fossa (Dandy‐Walker) |

Cyst in the posterior fossa (Dandy‐Walker) | Corpus callosum agenesis Hydrocephalus Cerebellar malformation, lower wall of 4th ventricle |

Enlarged ventricles supratentorially Cerebellar hypoplasia |

1 | 1 | 20+4 | 2 | 6 | Dilated ventricles |

| 15 | Hydrocephalus Corpus callosum agenesis Severe brainstem malformation |

Severe brainstem malformation | Corpus callosum agenesis Hydrocephalus |

Enlarged ventricles of the brain Fluid between frontal lobes Suspected corpus callosum agenesis |

3 | 3 | 21+3 | 3 | 4 | Dilated ventricles |

| 16 | Syndrome with multiple malformations Corpus callosum agenesis |

Multiple malformations Corpus callosum agenesis |

Corpus callosum agenesis Cerebellar malformation Defect of wall of 4th ventricle |

Corpus callosum agenesis Cerebellar malformation Defect of wall of the 4th ventricle Skull deformity |

2 | 2 | 16+3 | 4 | 5 | Suspicion of Meckel‐Gruber syndrome |

| 17 | Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele Arthrogryphosis‐like deformities of hip, knee, ankle Corpus callosum agenesis |

Cerebellar herniation Myelomeningocele |

Corpus callosum agenesis Cerebellar herniation |

Cerebellar herniation Closure defect lumbar spine Corpus callosum agenesis |

1 | 1 | 18+6 | 1 | 2 | Myelomeningocele |

| 20 | Acrania | Acrania | Anencephaly | Acrania | 1 | 1 | 19+4 | 1 | 5 | Acrania |

| 21 | Occipital bone defect Meningocele |

Occipital meningocele | Occipital encephalocele | Occipital bone defect with encephalocele | 2 | 2 | 17+6 | 1 | 5 | Encephalocele |

| 22 | Hydrocephalus Fluid/blood in the CNS Lissencephalya |

Intraventricular bleeding | Choroid plexus hemorrhage Hydrocephalus Hemosiderin at surface of cerebellum |

Enlarged supratentorial ventricles Normal 4th ventricle Intraventricular hemorrhage Choroid plexus hemorrhage Subarachnoidal hemorrhage |

1 | 1 | 21+6 | 4 | 5 | Hydrocephalus |

| 23 | Cortical migration disturbanceaGerminal matrix hemorrhage | Germinal matrix hemorrhage | Intraventricular hemorrhage | Enlarged lateral ventricles Normal 4th ventricle Intraventricular hemorrhage Small subarachnoidal hemorrhage |

1 | 1 | 21+3 | 3 | 4 | CNS anomaly |

| 24 | Holoprosencephaly Proboscis Hypotelorism |

Holoprosencephaly | Alobar holoprosencephaly | Alobar holoprosencephaly | 1 | 1 | 20+1 | 2 | 3 | Holoprosencephaly |

| 25 | Acrania | Acrania | Acrania | Acrania | 1 | 1 | 17+2 | 1 | 4 | Acrania |

| 31 | Hydrocephalus Corpus callosum agenesis No olfactory organ |

Corpus callosum agenesis Hydrocephalus |

Corpus callosum agenesis Hydrocephalus |

Corpus callosum agenesis | 1 | 1 | 20+5 | 5 | 5 | Corpus callosum agenesis Hydrocephalus |

At the first autopsy the CNS was assessed as normal, but after pre‐ and postnatal MR imaging provided additional information, a neuroautopsy was performed which verified schizencephaly.

Microscopic diagnosis at autopsy.

1: All major anomalies detected by MRI. 2: Some major anomalies detected by MRI, including the most clinically significant. 3: Some major anomalies detected by MRI, but not the most clinically significant. 4: None of the major anomalies detected by MRI.

Table 2.

Non‐CNS cases. Diagnoses according to fetal autopsy and MRI reports by two senior radiologists including a comparison, gestational age at termination of pregnancy, and days between termination and postmortem MRI and autopsy

| Case number | Diagnosis according to fetal autopsy | Most clinically significant major anomaly | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 1 | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 2 | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 1 vs fetal autopsy a | MRI diagnosis by radiologist 2 vs fetal autopsy a | Gestational age at termination of pregnancy (d) | Days from termination of pregnancy to MRI (d) | Days from termination of pregnancy to autopsy (d) | Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Single umbilical artery Heart pathology: Double inlet left ventricle Transposistion of the great arteries Aortic coarctation |

Double inlet left ventricle Transposistion of the great arteries |

Single cardiac ventricle | No pathological findings Heart difficult to examine |

3 | 4 | 18+1 | 1 | 4 | Heart anomaly |

| 4 | Did not go through autopsy | Excluded | Bilateral renal agenesis No urinary bladder |

Not assessed | Excluded | Excluded | 19+0 | 0 | 0 | No information |

| 5 | Heart pathology: VSD Single AV‐valve Omphalocele Dysmorphic features |

Heart malformation: VSD Omphalocele |

Corpus callosum agenesis Omphalocele Urinary bladder wall thickening |

Omphalocele Urinary bladder wall thickening |

3 | 3 | 19+0 | 0 | 2 | Multiple anomalies |

| 8 | VACTERL syndrome: Limb malformation Vertebral malformation Esophageal atresia Renal agenesis Pulmonary cysts |

Esophageal atresia Anal atresia Renal agenesis |

Bowel enlargement with high protein content Congenitial cystic adenomatoid malformation Vertebral malformation Corpus callosum agenesis Renal agenesis, no urinary bladder |

Bowel duplication Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation Renal agenesis No urinary bladder |

2 | 2 | 20+1 | 2 | 3 | Renal and urinary bladder agenesis |

| 9 | Multicystic dysplastic kidney | Multicystic dysplastic kidney | Multicystic right kidney Missing left kidney Urinary bladder seen |

Multicystic right kidney Missing left kidney No urinary bladder Cysts in the pelvic area |

2 | 2 | 18+1 | 0 | 4 | Multicystic right kidney Anhydramnion |

| 11 | Omphalocele Scoliosis Spina bifida OEIS‐complex: Omphalocele, extrophy of the cloaca, imperforate anus, spinal defects |

Omphalocele | Abdominal wall defect Scoliosis Myelomeningocele Cyst right flank |

Vertebral deformation Scoliosis Kyphosis Right lateral cyst next to spinal canal Myelomeningocele Cyst abdominal wall |

1 | 3 | 17+2 | 0 | 6 | Omphalocele Scoliosis |

| 12 | Cysts in the tentorium Bilateral diaphragmatic hernia Left ventricle hypoplasia Hydronephrosis and hydroureter Pulmonary hypoplasia |

Bilateral diaphragmatic hernia | Corpus callosum agenesis Congenitial brain malformation Bilateral diaphragmatic hernia Single heart ventricle |

Vermis deformity Congenital brain malformation Corpus callosum agenesis Normal ventricles of the brain Single heart ventricle Diaphragmatic hernia |

1 | 1 | 18+5 | 1 | 3 | Multiple anomalies Left ventricle hypoplasia |

| 14 | Thanatophoric dysplasia | Skeletal dysplasia | Short long bones | Short long bones | 3 | 3 | 18+1 | 5 | 7 | Skeletal dysplasia |

| 18 | Discrepancy between size of head and extremities Corpus callosum agenesis Syndrome? |

Immature brain Skeletal dysplasia | Normal CNS | Normal CNS | 4 | 4 | 20+3 | 5 | 6 | Discrepancy between size of head and extremities |

| 19 | Arthrogryphosis | Arthrogryphosis | Skull deformity Normal brain tissue Extremities not examined |

Extracranial fluid Skull deformity Short extremities |

4 | 4 | 17+5 | 7 | 7 | Arthrogryposis |

| 26 | Cytomegalovirus infection (prenatally diagnosed) Slightly dilated ventricles Misaligned hands and feet Micrognathia Pulmonary hypoplasia Dilated ventricles of the heart Hepatosplenomegaly |

Multiple organ anomalies | Intraventricular hemorrhage Hemosiderin in ventricular walls |

Intraventricular hemorrhage | 3 | 3 | 19+5 | 1 | 3 | Multiple anomalies |

| 27 | Trisomy 13 Proboscis Cyclopia Truncus arteriosus Holoprosencephaly Bowel malrotation |

Heart malformation Bowel malrotation Holoprosencephaly |

Alobar holoprosencephaly | Holoprosencephaly | 2 | 2 | 17+5 | 1 | 2 | Heart anomaly |

| 28 | Amniotic band syndrome | Bandlike marks of fetal hands and feet | Skull deformity, difficult to examine Bilateral club feet |

Severely deformed Bilateral club feet Severe varus deformity |

3 | 3 | 19+6 | 6 | 11 | Bilateral club feet |

| 29 | Pentalogy of Cantrell: Short umbilical cord Omphalocele Sternal defect Ectopic abdominal and thoracic organs Ectopic heart with ventricle septal defect Scolios Hypoplastic pelvis Missing left diaphragm |

Abdominal wall defect | Abdominal wall defect/hernia Kidneys and urinary bladder cannot be seen Heart partly in the hernia |

Kidneys and urinary bladder normal Abdominal wall normal Dilated bowel centrally |

1 | 4 | 16+5 | 1 | 4 | Pentalogy of Cantrell |

| 30 | Multiple malformations: CNS: Corpus callosum agenesis Hydrocephalus Atrophy of the cerebellum Occipital encephalocele Cerebellar herniation Renal cysts |

Cerebellar herniation Occipital encephalocele |

Deformed skull Corpus callosum agenesis |

Corpus callosum agenesis | 3 | 3 | 17+4 | 3 | 4 | CNS anomaly Hydrocephalus |

| 32 | Trisomy 18 (prenatally diagnosed) Intrauterine growth retardation Dysmorphic features Hypertelorism Low set ears Broad flat nose Clinodactyly of the 5th finger bilaterally Horseshoe kidney Misalignment of the heart |

Multiple organ anomalies | Corpus callosum agenesis Autolysis? |

Difficult to assess | 4 | 4 | 15+6 | 2 | 3 | IUGR |

| 33 | Arthrogryphosis Club foot right side Neck edema |

Arthrogryphosis | Hyperextension left knee Varus deformity right ankle |

Club foot right side | 3 | 3 | 21+5 | 2 | 3 | Arthrogryposis |

| 34 | Thanatophoric dysplasia Intrauterine asymmetric growth retardation |

Skeletal dysplasia | Corpus callosum agenesis Short long bones |

Suspected corpus callosum agenesis Short long bones |

2 | 2 | 17+6 | 1 | 2 | Skeletal dysplasia |

| 35 | Thanatophoric dysplasia Intrauterine asymmetric growth retardation |

Skeletal dysplasia | Corpus callosum agenesis Short limbs Suspected subarachnoidal hemorrhage Suspected pericardial hemorrhage |

Intraventricular hemorrhage Subarachnoidal hemorrhage Short limbs |

2 | 2 | 18+0 | 1 | 7 | Skeletal dysplasia |

1: All major anomalies detected by MRI. 2: Some major anomalies detected by MRI, including the most clinically significant. 3: Some major anomalies detected by MRI, but not the most clinically significant. 4: None of the major anomalies detected by MRI.

The time from termination of pregnancy to the postmortem MRI examination ranged from 0 to 7 days. The median was 1 day (Tables 1 and 2). The time from termination of pregnancy to autopsy ranged from 2 to 11 days. The median was 4 days (Tables 1 and 2).

Of 35 participants, 34 had a complete fetal autopsy and reports from the two radiologists. One case was excluded due to a missing autopsy report and a missing report from one of the radiologists (Tables 1 and 2).

Sixteen cases belonged to the CNS (examples are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4), five to the musculoskeletal, one to the cardiovascular, one to the urinary tract, and 11 cases had miscellaneous diagnoses (an example is shown in Figure 5) including complex anomalies, syndromes, cytomegalovirus infection and chromosomal aberrations. In the 16 cases related to the CNS, both radiologists reported all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies (categories one and two), in 15 (94%; CI 70%‐100%) cases. The one case not correctly diagnosed had severe brainstem malformation as the most clinically significant anomaly, which neither of the radiologists identified. The other anomalies, corpus callosum agenesis and hydrocephalus, however, were reported by both radiologists.

Figure 1.

Case 6. Transverse image of fetal brain with a mixed cystic and solid extra‐axial lesion in the right temporal region, which turned out to be a teratoma

Figure 2.

Case 22. Transverse image of brain showing intraventricular bleeding (black) originating from left germinal matrix (arrow)

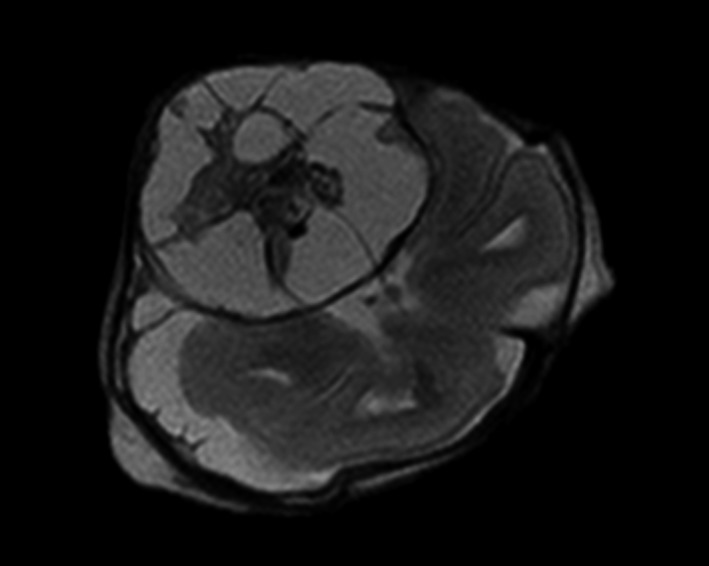

Figure 3.

Case 27. Coronal image showing alobar holoprosencephaly with a large monoventricle surrounded by a thin parenchyma (arrow)

Figure 4.

Case 31. Fetus with enlarged ventricles and signs of agenesis of the corpus callosum (arrow), which was confirmed by autopsy

Figure 5.

Case 8. Coronal image showing fetus with Vacterl syndrome. MRI revealed absent kidneys (white arrows point to adrenal glands), vertebral deformities (arrow head) and lung lesions (black arrow) but did not show the associated esophageal and anal atresia

In the 18 non‐CNS cases, both radiologists reported all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in six (33%; CI 13%‐59%) cases.

Of the five cases with musculoskeletal anomalies, the radiologists could see some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in two (40%; CI 5%‐85%) cases.

In the case with a cardiovascular diagnosis, none of the radiologists could see the major anomaly. In the case with the urinary tract anomaly, both radiologists could see some, including the most clinically significant anomalies.

Of the 11 cases with miscellaneous diagnoses, both radiologists reported all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in three (27%; CI 6%‐61%) cases. Radiologist number one detected all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in five (45%; CI 32%‐77%) cases, and radiologist number two detected anomalies in three (27%; CI 6%‐61%) cases.

In total, radiologist number one reported all or some, including the most clinically significant anomalies in 23 (68%; CI 49%‐83%) cases and radiologist number two in 21 (62%; CI 44%‐78%) cases.

In 21 (62%; CI 44%‐78%) cases, both radiologists held opinions that were consistent with the autopsy result (categories one and two). In 13 (38%; CI 22%‐66%) cases, at least one of the radiologists did not report all or some anomalies, including the most clinically significant. The gestational ages in those 13 cases varied from 15 weeks 6 days to 21 weeks 5 days.

In 31 (91%; CI 76%‐98%) cases, the radiologists had concordant opinions, meaning that the evaluations fell into the same category. Cohen's Kappa for the degree of agreement was 0.87. In three cases (numbers 3, 11 and 29) the reports from the radiologists differed (Table 2). The time interval from termination of pregnancy to MRI was 0‐1 day in these three cases.

Both radiologists found case number 32 with trisomy 18 and several anomalies difficult to assess. In this case, the time from termination of pregnancy to MRI was 2 days.

Corpus callosum agenesis was detected at autopsy in five cases, and both reviewers confirmed this by MRI in four cases. In addition, corpus callosum agenesis was diagnosed at MRI but not at autopsy in eight cases for radiologist number one, and in two cases for radiologist number two.

4. DISCUSSION

In contrast to most previous studies, all our cases involved fetuses from the second trimester, which makes our study unique. Both radiologists presented correct (categories one and two) reports compared with autopsy in 21/34 (62%) of all cases. The corresponding figure for the CNS cases was 94%. The radiologists held discordant opinions in only three cases. All of these were non‐CNS cases. This was not due to a longer interval between the termination and the MRI examination. Thus, the CNS anomalies were correctly assessed by the radiologists to a high degree, which confirms the results from previous studies.8, 15, 16 These studies, however, mostly included fetuses of higher gestational ages and infants.

We have shown that these satisfactory results also hold true for second trimester fetuses at about 18 weeks, where diagnoses are more difficult due to smaller fetal sizes.17 Our finding is of special importance in countries where there is a gestational age limit for pregnancy termination. Non‐CNS anomalies were too few to allow for a conclusion for separate organ systems. Previous reports have found a lower accuracy of postmortem MRI concerning non‐CNS cases, which is well in line with our results.15

In our study, we only had access to a 1.5 T scanner. It has been reported that a 3 T equipment improves the accuracy of postmortem MRI examinations of fetuses less than 20 gestational weeks.18 Such a difference could not be detected concerning the CNS but was evident for the thorax, heart and abdomen. Thus, our results for the non‐CNS anomalies would most probably have been improved if a 3 T scanner had been used. Even 9.4 T MRI equipment has previously been tested with excellent results.9 Such advanced machines, however, are not in clinical use in Sweden today, but may well be a valuable tool in the future. Another method, postmortem microfocus computed tomography, has recently been reported as an alternative to MRI for postmortem imaging of fetuses.19

One of the strengths of our study is the short time interval between the pregnancy terminations and the MRI examinations, with a median of just 1 day. Another strength is that two radiologists interpreted the MR images, enabling an assessment of the inter‐reviewer agreement. The high concordance between the radiologists supports that our results are generalizable. Moreover, the radiologists and the pathologist were blinded to each other's findings but not to the prenatal ultrasound findings. By having such an arrangement, we imitated the clinical situation where information from prenatal investigations is available for pathologists and radiologists performing postmortem examinations. Our choice of not using minimally invasive postmortem investigations12, 15 implies that there should be as few hesitations from women and partners concerning postmortem examinations as possible.

The rather small sample size can be seen as a limitation. However, compared with most previous studies concerning fetuses from early second trimester, our sample size is relatively large.7, 9 The long study period is also a limitation. It was due to practical problems such as the availability of an MR scanner and requiring women to accept that the fetus would undergo both an autopsy and an MR examination. Our hope to include a diversity of anomalies was not achieved. It is highly probable that colleagues who were responsible for the clinical care prioritized the CNS cases. A reason for this could be that a previous study from our department concerning prenatal MRI showed that fetal CNS anomalies were well diagnosed by MRI;20 thus, a selection bias is most probable.

MRI cannot reveal histological abnormalities, which is a weakness. Moreover, as evident from Table 1, histological examinations can provide valuable information in some cases. However, histological brain abnormalities are unlikely in cases with a normal MRI19 and major brain anomalies are well diagnosed by an MRI examination.11 Previous studies have shown that MRI can provide additional information in some cases, especially where a diagnosis is difficult using conventional autopsy due to autolysis.11 Corpus callosum agenesis was detected at MRI but not at autopsy in eight cases by radiologist number one and in two cases by radiologist number two. This can be compared with Thayyil et al,12 who reported on cases with corpus callosum agenesis identified by MRI but not seen at autopsy. It can only be speculated whether our cases represent false MRI diagnoses or examples of higher diagnostic capacity with MRI.

Studies on postmortem fetal MRI have been carried out for decades, but there is still no consensus regarding its place in clinical practice. To date, many smaller centers have to refer to regional hospitals, but modern techniques make it possible to send only the images for evaluation, since the problem is not the MRI equipment but the presence of a radiologist with special competence. Such new options make our results useful also for minor centers, although our study is performed at a single tertiary unit.

5. CONCLUSION

Postmortem fetal MRI can replace conventional autopsy for second trimester fetuses with CNS anomalies. For non‐CNS anomalies, the accuracy is lower; however, a postmortem MRI can still be of value when autopsy is not an option.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nicklas Pihlström at The Research and Development Center, Sörmland, for statistical support.

Hellkvist A, Wikström J, Mulic‐Lutvica, A . Postmortem magnetic resonance imaging vs autopsy of second trimester fetuses terminated due to anomalies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:865‐876. 10.1111/aogs.13548

REFERENCES

- 1. SBU . The Swedish Council on Technology assessment in Health Care. Routine ultrasound under pregnancy, report. Stockholm: ISBU, 1998.

- 2. Amini H, Antonsson P, Papadogiannakis N, et al. Comparison of ultrasound and autopsy findings in pregnancies terminated due to fetal anomalies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(10):1208‐1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyd PA, Tondi F, Hicks NR, Chamberlain PF. Autopsy after termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328(7432):137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dickinson JE, Prime DK, Charles AK. The role of autopsy following pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(6):445‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang X, Shelmerdine SC, Hurtado I, et al. Postmortem examination of human fetuses: a comparison of 2‐dimensional ultrasound with invasive autopsy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53:229‐238. 10.1002/uog.18828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thayyil S, Chandrasekaran M, Chitty LS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of post‐mortem magnetic resonance imaging in fetuses, children and adults: a systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75(1):e142‐e148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sebire NJ, Weber MA, Thayyil S, Mushtaq I, Taylor A, Chitty LS. Minimally invasive perinatal autopsies using magnetic resonance imaging and endoscopic postmortem examination (“keyhole autopsy”): feasibility and initial experience. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(5):513‐518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Harris DP, et al. Postmortem fetal MR imaging: comparison with findings at autopsy. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168(1):41‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thayyil S, Cleary JO, Sebire NJ, et al. Post‐mortem examination of human fetuses: a comparison of whole‐body high‐field MRI at 9.4 T with conventional MRI and invasive autopsy. Lancet. 2009;374(9688):467‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cannie M, Votino C, Moerman P, et al. Acceptance, reliability and confidence of diagnosis of fetal and neonatal virtuopsy compared with conventional autopsy: a prospective study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39(6):659‐665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffiths PD, Variend D, Evans M, et al. Postmortem MR imaging of the fetal and stillborn central nervous system. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(1):22‐27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thayyil S, Sebire NJ, Chitty LS, et al. Post‐mortem MRI versus conventional autopsy in fetuses and children: a prospective validation study. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):223‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arthurs OJ, Barber JL, Taylor AM, Sebire NJ. Normal perinatal and paediatric postmortem magnetic resonance imaging appearances. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45(4):527‐535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clopper C, Pearson S. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404‐413. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Breeze ACG, Jessop FA, Set PAK, et al. Minimally‐invasive fetal autopsy using magnetic resonance imaging and percutaneous organ biopsies: clinical value and comparison to conventional autopsy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(3):317‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vullo A, Panebianco V, Cannavale G, et al. Post‐mortem magnetic resonance foetal imaging: a study of morphological correlation with conventional autopsy and histopathological findings. Radiol Med. 2016;121(11):847‐856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jawad N, Sebire NJ, Wade A, Taylor AM, Chitty LS, Arthurs OJ. Body weight lower limits of fetal postmortem MRI at 1.5 T. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(1):92‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kang X, Cannie MM, Arthurs OJ, et al. Post‐mortem whole‐body magnetic resonance imaging of human fetuses: a comparison of 3‐T vs 1.5‐T MR imaging with classical autopsy. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(8):3542‐3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hutchinson JC, Kang X, Shelmerdine SC, et al. Postmortem microfocus computed tomography for early gestation fetuses: a validation study against conventional autopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(4):445.e1‐445.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amini H, Axelsson O, Raiend M, Wikström J. The clinical impact of fetal magnetic resonance imaging on management of CNS anomalies in the second trimester of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(12):1571‐1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]