ABSTRACT

Introduction: Eculizumab is effective and well tolerated in patients with antiacetylcholine receptor antibody‐positive refractory generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG; REGAIN; NCT01997229). We report an interim analysis of an open‐label extension of REGAIN, evaluating eculizumab's long‐term safety and efficacy. Methods: Eculizumab (1,200 mg every 2 weeks for 22.7 months [median]) was administered to 117 patients. Results: The safety profile of eculizumab was consistent with REGAIN; no cases of meningococcal infection were reported during the interim analysis period. Myasthenia gravis exacerbation rate was reduced by 75% from the year before REGAIN (P < 0.0001). Improvements with eculizumab in activities of daily living, muscle strength, functional ability, and quality of life in REGAIN were maintained through 3 years; 56% of patients achieved minimal manifestations or pharmacological remission. Patients who had received placebo during REGAIN experienced rapid and sustained improvements during open‐label eculizumab (P < 0.0001). Discussion: These findings provide evidence for the long‐term safety and sustained efficacy of eculizumab for refractory gMG. Muscle Nerve 2019

Keywords: eculizumab, MG‐ADL, MGC, MG‐QOL15, myasthenia gravis, QMG

Short abstract

Abbreviations

- AChR+

antiacetylcholine receptor antibody‐positive

- aHUS

atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome

- CI

confidence interval

- gMG

generalized myasthenia gravis

- IST

immunosuppressive therapy

- IVIg

intravenous immunoglobulin

- MG

myasthenia gravis

- MG‐ADL

Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living

- MGC

Myasthenia Gravis Composite scale

- MGFA

Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America

- MG‐QOL15

Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15

- PNH

paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- QMG

Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale

Generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) is a chronic, rare autoimmune disorder that is characterized by severe muscle weakness.1 Autoantibodies to the acetylcholine receptor are present in 73%–88% of patients with gMG.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 These autoantibodies initiate accelerated endocytosis and degradation of acetylcholine receptors and complement‐mediated destruction of the neuromuscular junction, resulting in further reductions in acetylcholine and sodium channel receptors.1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The complement‐mediated pathological membrane changes reduce the efficiency of neurotransmission at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in the characteristic muscle weakness and fatigability that are observed in patients with MG.1, 14

Some patients (10%–15%) with MG do not respond adequately to long‐term treatment with corticosteroids or multiple steroid‐sparing immunosuppressive therapies (IST), experience intolerable side effects, or require ongoing treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange.1, 15, 16, 17, 18 Persistent myasthenic symptoms14, 15, 16, 18, 19 can adversely affect activities of daily living, including breathing, talking, swallowing, walking, and functional muscle strength as well as quality of life.15 Patients also have increased risks of myasthenic exacerbations and crises; an increased requirement for rescue therapies; and more frequent inpatient hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and emergency room visits.20, 21

Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically binds with high affinity to human terminal complement protein C5. This inhibits enzymatic cleavage of C5 to C5a and C5b, thereby preventing C5a‐induced chemotaxis of proinflammatory cells and formation of the C5b‐induced membrane attack complex.22 Eculizumab was shown to have efficacy and was well tolerated in the 6‐month randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled REGAIN study (NCT01997229), producing clinically meaningful improvements in activities of daily living, muscle strength, functional ability and quality of life in patients with antiacetylcholine receptor antibody‐positive (AChR+) refractory gMG.14 Eculizumab is approved for the treatment of adults with AChR+ gMG, in addition to paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

The open‐label extension study of the phase 3 REGAIN (NCT02301624) was designed to evaluate the long‐term safety and efficacy of eculizumab in patients with AChR+ refractory gMG. Here we report data from a preplanned interim analysis that was based on a median duration of almost 2 years of eculizumab treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Participants who completed the 6‐month, double‐blind REGAIN study could enter this extension study. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria for the REGAIN study have been published previously.14 In brief, adults (aged ≥18 years) with the following were eligible for REGAIN: confirmed gMG with positive serology for acetylcholine receptor antibodies, an MG Activities of Daily Living (MG‐ADL) total score of 6 or higher, and failed treatment with 2 or more ISTs or at least 1 IST with requirement for chronic IVIg or plasma exchange therapy over the preceding 12 months. Patients were excluded if they had a history of thymoma or other thymic neoplasm, had undergone thymectomy in the 12 months before screening, experienced ocular‐only MG symptoms (Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America [MGFA] class I) or myasthenic crisis (MGFA class V) at screening, or required treatment with IVIg or plasma exchange within the 4 weeks before randomization.14

Eligible patients who elected to continue into the open‐label extension were required to enter it within 2 weeks of completing REGAIN. The first patient was enrolled on November 12, 2014, and the last patient was enrolled on March 4, 2016. Participants received open‐label eculizumab until it was otherwise available to them, up to a maximum of 4 years in the extension study. The study was completed in January 2019.

All patients provided written, informed consent. Written approval for the study protocol and all study amendments was obtained from independent ethics committees or institutional review boards at all participating sites. All human studies were approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standard laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Dosing and Administration

Patients who received eculizumab in REGAIN continued to receive eculizumab during the open‐label study (eculizumab/eculizumab group). Those who received placebo in REGAIN started eculizumab treatment when they entered the open‐label study (placebo/eculizumab group).

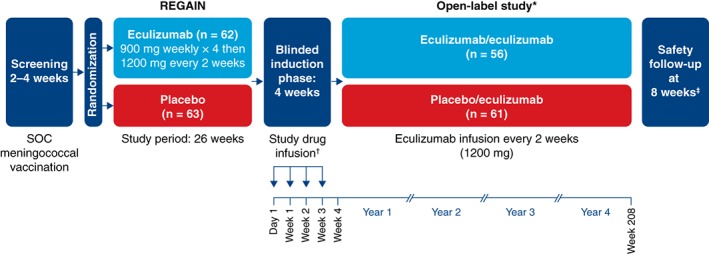

To preserve the blinded nature of REGAIN, patients who entered the open‐label study first underwent a 4‐week blinded induction phase during which investigators, patients, and study personnel remained blinded to all treatment assignments (Fig. 1). During this phase, patients who had been assigned to eculizumab in REGAIN received eculizumab 1,200 mg (4 vials) on day 1 and week 2 and placebo (4 vials) at weeks 1 and 3. Patients who had been assigned to placebo in REGAIN received eculizumab (900 mg, 3 vials) and placebo (one vial) on day 1 and at weeks 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 1). In the open‐label maintenance phase, which started at week 4, all patients received open‐label eculizumab (1,200 mg) every 2 weeks.

Figure 1.

Study design. *Interim data are reported from the December 31, 2017 data cutoff point. †During the blinded induction phase of the open‐label study, patients received eculizumab (1,200 mg; 4 vials) at day 1 and week 2 and received placebo (4 vials) at weeks 1 and 3 (eculizumab/eculizumab group) or placebo (1 vial) plus eculizumab (900 mg; 3 vials) each week (placebo/eculizumab group). ‡Patients who withdrew or discontinued after receiving any amount of eculizumab were required to complete a safety follow‐up visit 8 weeks after their last eculizumab dose. SOC, standard of care.

Procedures

To mitigate the increased risk of meningococcal infection associated with terminal inhibition of the complement system,23 all patients in REGAIN were required to receive Neisseria meningitidis vaccination according to local guidelines at least 2 weeks before starting blinded study treatment; if they were not vaccinated at the appropriate time, patients received prophylactic antibiotics until 2 weeks after vaccination. In the open‐label study, patients were revaccinated according to local guidelines, which recommend revaccinating patients after 2–5 years to maintain active coverage.

Patients who entered the open‐label study were on a stable regimen of concomitant MG therapies, including ISTs that could include but were not limited to corticosteroids, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide. Adjustment of concomitant MG therapies, including ISTs, was permitted at the discretion of the study investigator but was not required by the study protocol. Rescue therapy (e.g., high‐dose intravenous corticosteroids, IVIg, or plasma exchange) was available at the discretion of the study investigator for patients who experienced disease exacerbation.

Validated MG assessments of activities of daily living, muscle strength, functional ability, and quality of life were used to evaluate the long‐term efficacy of eculizumab. These assessments consisted of the MG‐ADL scale,24 the Quantitative MG scale (QMG),25 the MG Composite scale (MGC),26 and the 15‐item MG Quality of Life questionnaire (MG‐QOL15).27 MG‐ADL, QMG, MGC, and MG‐QOL15 assessments were performed on day 1. MG‐ADL, QMG, and MGC assessments were performed weekly from week 1 through week 3. MG‐ADL, QMG, MGC, and MG‐QOL15 assessments were then performed at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 26, 40, and 52 in year 1, every 6 months thereafter, and at each patient's end of study visit. These same 4 efficacy measures were used in the REGAIN study.14

Outcomes

We report an interim analysis of safety and efficacy data, including the occurrence of adverse events, and changes in activities of daily living, muscle strength, functional ability, and quality of life over time using 4 MG‐specific disease measures (data cutoff December 31, 2017).

The primary objective of this open‐label study was to evaluate the long‐term safety of eculizumab. Safety was assessed by incidences of adverse events, serious adverse events, study discontinuations due to adverse events, exacerbations, hospital admissions, and rescue therapy administrations. Adverse events were coded by preferred term by using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Version 20.1. The number of patients who experienced an adverse event of special interest (meningococcal infections, aspergillus infections, sepsis, any serious infections, infusion‐related reactions, serious cutaneous reactions, cardiac disorders, or angioedema) during each 3‐month study period was determined. For this study, a clinical deterioration/exacerbation was defined as 1 of the following: MG crisis, substantial symptomatic worsening (to a score of 3 or a 2‐point worsening on any 1 of the individual MG‐ADL items, excluding ocular items), or health in jeopardy if rescue therapy was not given, as determined by the treating physician. The exacerbation and hospitalization event rates were compared with rates during the year before entering REGAIN (collected at REGAIN baseline assessment); the rescue therapy event rate was compared with the rate in the placebo group during REGAIN.

The primary efficacy endpoint was change in mean MG‐ADL total score from baseline over time. Changes from REGAIN and open‐label baselines were evaluated. Secondary efficacy endpoints included changes from baseline in mean QMG, MGC, and MG‐QOL15 total scores over time and the proportions of patients achieving clinically meaningful responses to eculizumab, prospectively defined as improvements from baseline of at least 3 points in MG‐ADL total score or at least 5 points in QMG total score.28, 29, 30 Other efficacy endpoints included MGFA postinterventional status, a disease‐specific outcome measure that captures the physician's global assessment of the patient's clinical status after initiation of MG treatment.31 The same neurologist skilled in evaluating patients with MG assessed the MGFA postinterventional status throughout the study (at weeks 26 and 40 and then every 26 weeks until end of study/early termination) according to the following categories relative to baseline: improved (a substantial decrease in clinical manifestations or in MG medications), unchanged (no substantial change in clinical manifestations or reduction in MG medications), or worse (a substantial increase in clinical manifestations or MG medications).31 Patients who had improved were also evaluated for minimal manifestation and pharmacological remission status.31

Statistical Analysis

Safety analyses were performed for all patients who received at least 1 dose of eculizumab in the open‐label study (safety set). Efficacy analyses were conducted by using the full analysis set, which comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of eculizumab in the open‐label study and had at least 1 postdose efficacy assessment.

For exacerbations, hospitalizations, and rescue therapy use, model‐based event rates per 100 patient‐years were calculated. This was based on a generalized estimating equation Poisson regression repeated‐measures model with the number of events as the dependent variable, the logarithm of patient‐years as the offset variable, and the study phase indicator (prestudy, placebo, or eculizumab) as the factor assuming a compound symmetry correlation structure.

Two baselines were used for the efficacy analyses, REGAIN baseline, defined as assessment at day 1 in the REGAIN study; and open‐label baseline, defined as the last available assessment before first eculizumab infusion (this was typically the day‐1 assessment in the open‐label study; when the day‐1 data were missing, the most recent assessment from REGAIN was used as the open‐label baseline). Changes from baseline in MG‐ADL, QMG, MGC, and MG‐QOL15 total scores at a particular visit were based on repeated‐measures models. Separate repeated‐measures models were used for the eculizumab/eculizumab and placebo/eculizumab groups because patients in the eculizumab/eculizumab group had already received 6 months of eculizumab in REGAIN. Assessing the change from the open‐label baseline allowed for evaluation of the eculizumab treatment effect in the placebo/eculizumab arm and the effect of continued, long‐term treatment in the eculizumab/eculizumab arm. The change from REGAIN baseline allowed for an assessment of all changes from time of entry to REGAIN. Missing efficacy endpoint assessments were not imputed.

The responder analyses measured the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful improvements from REGAIN baseline. The proportions of patients experiencing this improvement with and without prior on‐study rescue therapy were determined at each visit for both groups. Exact (Clopper–Pearson) 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the true proportions are presented.

Data are presented as least‐squares means (changes from open‐label baseline) and 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). This study did not have a data monitoring committee.

RESULTS

In this interim analysis, 117 of the 118 patients who completed REGAIN enrolled in the open‐label study (eculizumab/eculizumab, 56; placebo/eculizumab, 61) and were included in the safety analysis, and 116 patients were included in the efficacy analysis (eculizumab/eculizumab, 56; placebo/eculizumab, 60); approval for the inclusion of 1 patient in the interim efficacy analyses was not given by their national health authority.

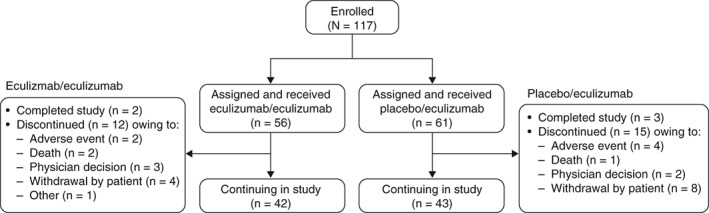

At the time of data cutoff, study participation was ongoing for 73% of patients. Five patients (eculizumab/eculizumab, 2; placebo/eculizumab, 3) had completed the study. Among the 27 patients who discontinued the study, 6 patients discontinued because of 1 or more adverse events, and 3 patients died. In addition, study investigators withdrew 5 patients, 12 patients withdrew consent, and 1 patient discontinued for a reason described as “other” (Fig. 2) after a median period of eculizumab therapy of 379 days because of various factors including ongoing comorbidities, perceived lack of clinical benefit, and logistical problems with clinic attendance (Supp. Info. Table 1).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition through December 31, 2017. In total, 117 patients enrolled in the open‐label study, of whom 56 had received eculizumab and 61 had received placebo during REGAIN. As of December 31, 2017, twenty‐seven patients had discontinued, 5 patients had completed the study, and 85 patients were continuing in the study.

Patient demographics for the study population were reported for REGAIN.14 Patient characteristics were similar between the eculizumab/eculizumab and placebo/eculizumab groups (Table 1). In total, 38 patients required revaccination against N meningitidis (eculizumab/eculizumab, 20; placebo/eculizumab, 18).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients entering the open‐label study by treatment group (safety set)

| Variable | Eculizumab/ eculizumab, n = 56 | Placebo/ eculizumab, n = 61 |

All patients, N = 117 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), y* | 47.2 (15.5) | 47.5 (17.9) | 47.4 (16.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 18 (32.1) | 20 (32.8) | 38 (32.5) |

| Women | 38 (67.9) | 41 (67.2) | 79 (67.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 3 (5.4) | 16 (26.2) | 19 (16.2) |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (1.7) |

| White | 47 (83.9) | 41 (67.2) | 88 (75.2) |

| Multiple | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 4 (7.1) | 2 (3.3) | 6 (5.1) |

| MG duration, mean (SD), y† | 10.7 (7.9) | 9.8 (8.5) | 10.2 (8.2) |

MG, myasthenia gravis; SD, standard deviation.

On day 1 of the open‐label extension study.

Time from MG diagnosis to first dose date in the open‐label extension study.

The median duration of eculizumab treatment for all 117 patients during the open‐label study was 22.7 months (range, 1 day to 37.3 months). Reported data are based on 227 patient‐years of open‐label eculizumab exposure at the time of data cutoff.

The most common adverse events were headache and nasopharyngitis, which were experienced by 37.6% and 31.6% of patients, respectively (Table 2). The most common serious adverse event was MG worsening, which occurred in 12.8% of patients (Table 2). Three patients experienced a serious adverse event of MG crisis, which resulted in study discontinuation for 2 of them. Six patients withdrew from the study because of a serious adverse event. All serious adverse events are listed in Supporting Information Table 2.

Table 2.

Safety outcomes in all patients during the open‐label study

| Event | Events, n | Patients experiencing an event, n (%) | Events per 100 PY* |

|---|---|---|---|

| All adverse events | 1,816 | 113 (96.6) | 800.0 |

| Most common adverse events† , ‡, >10% of all patients, N = 117 | |||

| Headache | 71 | 44 (37.6) | 31.3 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 76 | 37 (31.6) | 33.5 |

| Diarrhea | 40 | 27 (23.1) | 17.6 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 55 | 27 (23.1) | 24.2 |

| Myasthenia gravis§ | 40 | 23 (19.7) | 17.6 |

| Arthralgia | 29 | 22 (18.8) | 12.8 |

| Nausea | 26 | 21 (17.9) | 11.5 |

| Pain in extremity | 21 | 18 (15.4) | 9.3 |

| Cough | 21 | 17 (14.5) | 9.3 |

| Fatigue | 21 | 17 (14.5) | 9.3 |

| Urinary tract infection | 32 | 17 (14.5) | 14.1 |

| Influenza | 24 | 16 (13.7) | 10.6 |

| Gastroenteritis | 15 | 14 (12.0) | 6.6 |

| Bronchitis | 22 | 13 (11.1) | 9.7 |

| Pyrexia | 17 | 13 (11.1) | 7.5 |

| Fall | 24 | 12 (10.3) | 10.6 |

| All serious adverse events | 147 | 52 (44.4) | 64.8 |

| Most common (≥2 patients) MG‐ and infection‐related serious adverse events† , ‡ , ‖ | |||

| Myasthenia gravis§ | 28 | 15 (12.8) | 12.3 |

| Death | 3 | 3 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Myasthenia gravis crisis | 3 | 3 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Pyrexia | 3 | 3 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Gastroenteritis | 3 | 3 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Pneumonia | 3 | 3 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Sepsis | 3 | 3 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Bronchitis | 3 | 2 (1.7) | 1.3 |

| Influenza | 2 | 2 (1.7) | 0.9 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 | 2 (1.7) | 0.9 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 | 2 (1.7) | 1.3 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 2 | 2 (1.7) | 0.9 |

MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; MG, myasthenia gravis; PY, patient year.

Patient‐years is the sum of all years for all patients and observed event rate is the number of events per PY multiplied by 100.

When a patient had more than 1 adverse event for a particular preferred term, that patient was counted only once for that preferred term.

MedDRA preferred term.

Worsening (increased frequency and/or intensity) of a preexisting condition, including myasthenia gravis, is considered to be an adverse event.

Serious adverse events are adverse events that are life‐threatening or result in death, hospitalization, or persistent or significant disability or incapacity, are congenital anomalies or birth defects, or are important medical events. All serious adverse events in the open‐label study are listed in Supporting Information Table 1.

At the time of this interim analysis, 3 deaths had occurred. The death of 1 patient who was concomitantly receiving azathioprine was attributed to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with cytomegalovirus infection of the liver resulting in multiple organ failure. The second death was attributed to end‐stage liver disease in a patient with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis and a medical history of fatty liver, and the third death was due to pulmonary embolism that occurred in a patient who was in the hospital recovering from cardiogenic shock secondary to sepsis complicated by deep vein thrombosis.

During the open‐label study, 22 (18.8%) patients experienced an infectious event of special interest, including 5 cases of sepsis, septic shock, or pseudomonas sepsis and 1 case each of aspergillus, cytomegalovirus, and pseudomonas infection (Supp. Info. Table 3). The proportion of patients experiencing these infections or other adverse events of special interest (infusion‐related reactions, serious cutaneous reactions [urticaria], and cardiac disorders) was in line with that observed during REGAIN. Similar proportions of patients in the eculizumab/eculizumab and placebo/eculizumab groups experienced these adverse events, and rates did not change over time in the open‐label study (Supp. Info. Table 4). There were no cases of meningococcal infection at the interim data cutoff date; 1 case, which was resolved with antibiotic treatment, occurred after this date.

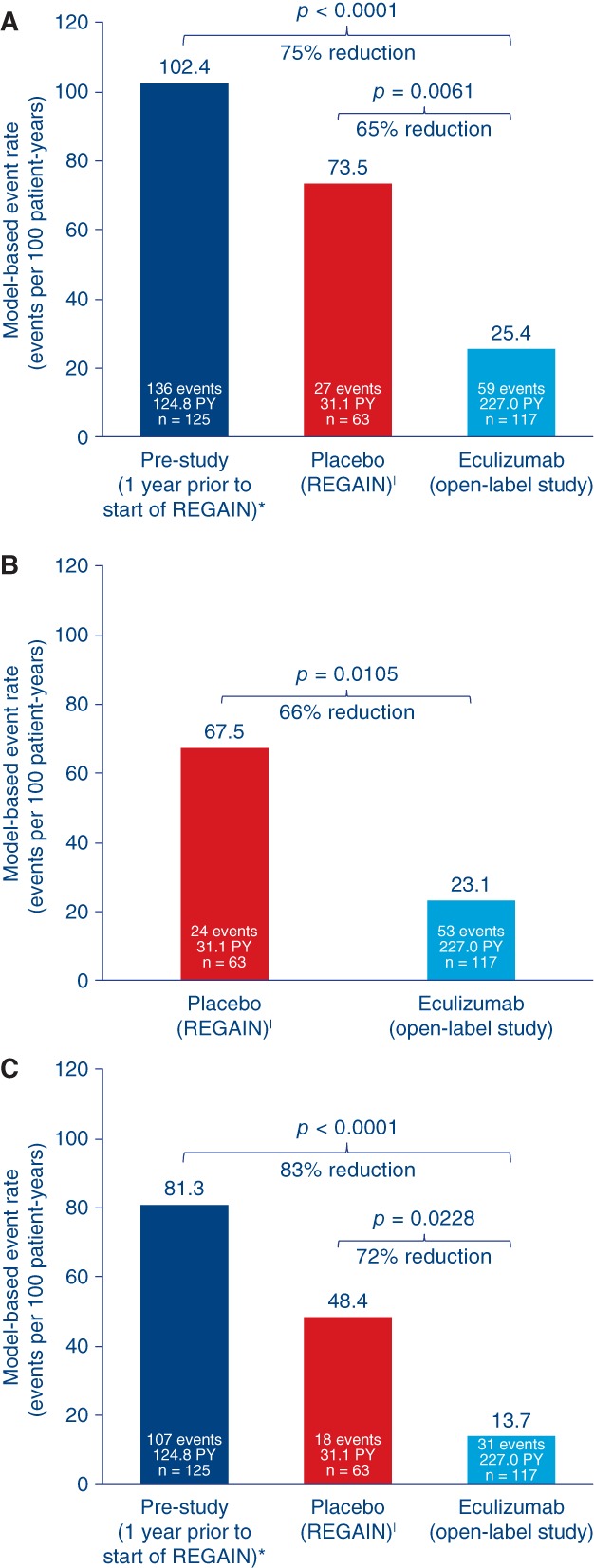

In total, 59 MG exacerbations (including MG crises, substantial symptomatic worsening, and health in jeopardy if rescue therapy was not given) were experienced by 29 patients during the open‐label study before data cutoff. Compared with the year before REGAIN start, the exacerbation rate was reduced by 75.2% (prestudy, 102.4 exacerbations per 100 patient‐years; open‐label study, 25.4 exacerbations per 100 patient‐years; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). The exacerbation rate was also significantly lower than in the REGAIN placebo group (73.5 exacerbations per 100 patient‐years; P = 0.0061). The rate of rescue therapy use was 23.1 events per 100 patient‐years in the open‐label study, compared with 67.5 events per 100 patient‐years in patients receiving placebo during REGAIN (P = 0.0105; Fig. 3). The rate of MG‐related hospitalizations was reduced by over 80% compared with the year before REGAIN start (prestudy, 81.3 hospitalizations per 100 patient‐years; open‐label study, 13.7 hospitalizations per 100 patient‐years; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). It was also lower than in the REGAIN placebo group (48.4 hospitalizations per 100 patient‐years; P = 0.0228; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment effects on event rates for all reported exacerbations (A), rescue therapy administration (exacerbation events requiring rescue therapy (B), and MG‐related hospitalization (exacerbation events requiring rescue therapy (C). Model‐based event rate per 100 patient‐years is based on a generalized estimating equation Poisson regression repeated‐measures model with the number of events as the dependent variable, the logarithm of patient‐years as the offset variable, and the study phase indicator (prestudy, placebo, or eculizumab) as the factors assuming a compound symmetry correlation structure. *Patient‐year for prestudy accounted for a maximum of 365 days for each patient prior to screening. |Changes in event rates in this group reflect the response to placebo that was observed during REGAIN. PY, patient‐year.

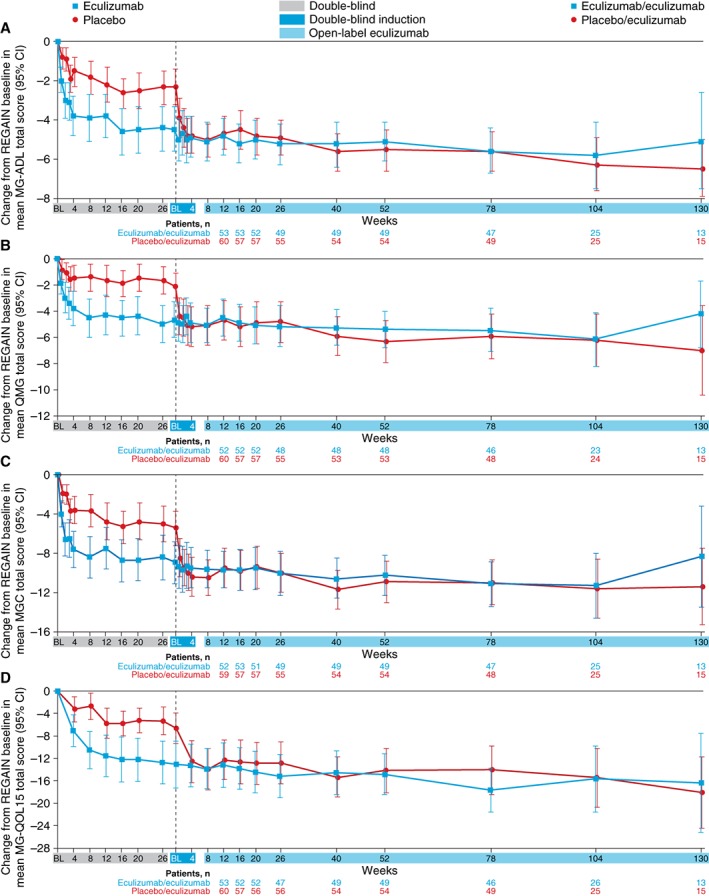

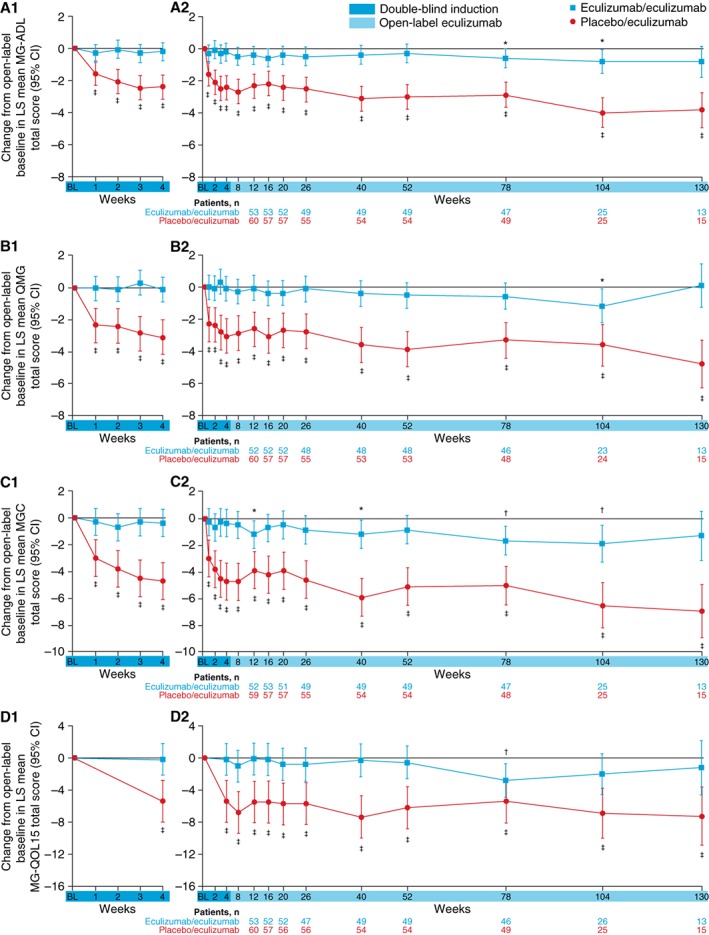

Improvements that had been demonstrated for patients during 6 months of blinded eculizumab in REGAIN were sustained during the open‐label study for a total maximum eculizumab treatment duration of 3 years (eculizumab/eculizumab group; Fig. 4). The mean MG‐ADL total score from open‐label baseline did not change significantly in this group at each assessment (−0.8 change from baseline to week 130 [n = 13]; P = 0.0990; Fig. 5A2). This sustained treatment effect was also supported by similar findings with mean total scores for QMG (0.1 change from baseline to week 130 [n = 13]; P = 0.8949; Fig. 5B2), MGC (−1.3 change from baseline to week 130 [n = 13]; P = 0.1531; Fig. 5C2), and MG‐QOL15 (−1.2 change from baseline to week 130 [n = 13]; P = 0.4756; Fig. 5D2).

Figure 4.

Change from REGAIN baseline to week 130 in the open‐label extension study in MG‐ADL (A), QMG (B), MGC (C), and MG‐QOL15 (D) total scores (mean [95% CI]) by treatment arm over time (full analysis set). Patient numbers were not the same for each assessment. BL, baseline; CI, confidence interval; MG‐ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; MGC, Myasthenia Gravis Composite scale; MG‐QOL15, Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale.

Figure 5.

Change from open‐label baseline in MG‐ADL to week 4 (double‐blind induction phase only; A1), MG‐ADL to week 130 (A2), QMG to week 4 (B1), QMG to week 130 (B2), MGC to week 4 (C1), MGC to week 130 (C2), MG‐QOL15 to week 4 (D1), and MG‐QOL15 to week 130 (D2); total scores (LS mean [95% CI]) by treatment group over time (full analysis set). Patient numbers were not the same for each assessment. The stability of scores during the open‐label study in the eculizumab/eculizumab group is evidence of the maintenance of improvements achieved during eculizumab treatment in REGAIN in these patients. The rapid and significant improvements in the placebo/eculizumab group are evidence of these patients’ response to commencing eculizumab at the start of the open‐label study, including during the initial 4‐week blinded induction phase. *P ≤ 0.05, † P ≤ 0.01, ‡ P ≤ 0.0001 compared with open‐label baseline, repeated‐measures analysis. BL, baseline; CI, confidence interval; LS, least‐squares; MG‐ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; MGC, Myasthenia Gravis Composite scale; MG‐QOL15, Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis scale.

Patients who had received placebo during REGAIN experienced a rapid and significant improvement when they commenced eculizumab at the start of the open‐label extension (Fig. 5A1, B1, C1, D1). Improvements from open‐label baseline in mean MG‐ADL total score as well as QMG, MGC, and MG‐QOL15 total scores were of similar magnitude to those experienced by eculizumab‐treated patients in REGAIN. The mean change from open‐label baseline was statistically significant as early as the first visit after eculizumab administration (assessed at week 1 for MG‐ADL [−1.6 from baseline], QMG [−2.3 from baseline], and MGC [−3.0 from baseline] and at week 4 for MG‐QOL15 [−5.4 from baseline]; all P < 0.0001; Fig. 5A1, B1, C1, D1), with over half of the improvement occurring in the first 3 months. These improvements were sustained over 30 months (mean change in MG‐ADL total score from open‐label baseline to month 30, −3.8; P < 0.0001; n = 15).

At the last assessment for this interim analysis, 55.2% of patients in the open‐label study demonstrated a clinically meaningful response in activities of daily living (at least a 3‐point improvement from REGAIN baseline in MG‐ADL total score without use of rescue therapy). When analysis was performed regardless of rescue therapy, 71.6% of patients experienced this improvement. Over one‐third (39.7%) of patients experienced a clinically meaningful response in muscle strength (at least a 5‐point improvement from REGAIN baseline in QMG total score without rescue therapy use), and 48.3% experienced this improvement regardless of rescue therapy use.

At the final MGFA postinterventional status evaluation before this data cutoff, 74.1% (86/116) of patients were reported by their investigator to have clinically improved compared with REGAIN baseline. In addition, most (65/116 [56.0%]) patients were deemed to have achieved minimal manifestations of MG or pharmacological remission.

DISCUSSION

Inhibition of terminal complement activity with eculizumab is a biologically rational approach to prevent damage at the neuromuscular junction in patients with AChR+ refractory gMG.22 Eculizumab has been reported to produce rapid and clinically meaningful improvements in activities of daily living, muscle strength, functional ability, and quality of life and is well tolerated in these patients.14 This interim analysis of the open‐label extension study provides evidence that the safety and efficacy of eculizumab in this patient population are sustained with long‐term treatment.

The safety data for eculizumab in this study are in line with the current safety profile in patients with refractory gMG and with its well‐characterized safety profile (on the basis of >10 years of postmarketing experience) in the other approved indications, PNH and aHUS.14, 32, 33, 34 Consistent with the mode of action of eculizumab, infections were the most commonly reported events among the adverse events of special interest. The prevalence of infections and other events of special interest did not change with continued eculizumab exposure. To mitigate the risk of meningococcal infection, patients were required to receive meningococcal vaccination as described in Materials and Methods. There were no occurrences of meningococcal infection by data cutoff; 1 nonfatal case after this date has been reported. Three fatal events were reported in patients with important comorbidities that likely contributed to the clinical outcome.

The rapid response to eculizumab across multiple disease‐specific measures in patients who had previously received placebo confirms the effect of eculizumab recorded in REGAIN and exceeded the response to placebo that was observed during REGAIN. The maintenance of this effect in patients who received eculizumab for up to 3 years provides evidence of its durability. The open‐label study not only supports and extends the body of evidence for the treatment effect of eculizumab but also provides new data regarding its positive impact on clinical burden in patients who experience persistent MG symptoms despite having a history of using multiple ISTs. Among such patients, rates of potentially life‐threatening exacerbations,35 with consequent hospitalizations and rescue therapy use, are typically high.20 We have demonstrated that eculizumab treatment significantly reduces the rates of MG exacerbations and MG‐related hospitalizations in comparison with the last complete year before entering the study and the rate of rescue therapy requirement compared with placebo‐treated patients in REGAIN. In addition, most patients were reported by their physicians to have shown global clinical improvements during the open‐label study, and over half achieved minimal manifestations status or pharmacological remission according to MGFA postinterventional status evaluation. These interim results add to the findings of REGAIN in providing evidence of the range of clinical benefits provided by eculizumab and the impact it has on alleviating the burden of disease in patients with previously refractory gMG.

These results add to the evidence that complement protein C5 inhibition is a relevant therapeutic target in AChR+ refractory gMG and provide evidence of the long‐term benefits of complement inhibition by eculizumab for patients with this disease. Additional investigations into the structural and functional changes at the neuromuscular junction in response to eculizumab that correlate with clinical improvement in patients with MG may help to build on the current preclinical evidence,36, 37, 38 fully characterize the pathophysiology of MG including the role of complement inhibition, and elucidate the mechanism underlying the rapid response to eculizumab.

The main limitation of this study is the open‐label design, which could yield unconscious bias in reporting, particularly of adverse events. The blinded induction phase was designed to preserve the blinded nature of REGAIN during the period of potential initial response. Although the lack of a control group may also be considered a limitation, comparisons can be made with the placebo group in REGAIN and with pre‐REGAIN data for the overall study population. Because over 90% of REGAIN participants enrolled in the open‐label extension study, selection bias based on inclusion in the open‐label study population is unlikely.

Future analyses of long‐term eculizumab data, including changes in IST and corticosteroid use during eculizumab therapy; the time course of clinical improvements; and achievement of minimal manifestations will be important for understanding the role of eculizumab in the treatment of individuals with refractory gMG.

In conclusion, results of this interim analysis confirm the rapid and robust response to eculizumab that was observed during REGAIN and support the long‐term clinical effectiveness and safety of eculizumab in patients with AChR+ refractory gMG who previously experienced persistent symptoms and significant morbidities despite concomitant IST. Improvements in activities of daily living, muscle strength, functional ability, and quality of life were maintained through 3 years in patients receiving eculizumab. This study also provides new evidence for other clinical benefits of eculizumab in these patients, including reducing the frequency of disease exacerbations. The completion of this open‐label extension study will provide additional opportunities to continue studying and understanding the long‐term benefits of eculizumab in patients with gMG.

The authors thank the patients who took part in REGAIN and the open‐label extension study as well as their families; all of the investigators and collaborators for their contributions to the completion of the study; Angela Kaya, PhD, and Gus Khursigara, PhD, (formerly of Alexion Pharmaceuticals) and Róisín Armstrong, PhD, Diaa Diab, MBBS, and Kelley Capocelli, MD, (Alexion Pharmaceuticals) for critical review of the manuscript, and Cindy Lane, MS, (Alexion Pharmaceuticals) for clinical study oversight. We acknowledge Vicky Sanders, PhD, and Ruth Gandolfo, PhD (Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK), who provided medical writing support in the production of this manuscript (funded by Alexion Pharmaceuticals). All members of the REGAIN study group are listed in the Supporting Information materials.

Ethical Publication Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1 Patients who discontinued from open‐label extension study.

Supplementary Table S2 All serious adverse events.

Supplementary Table S3 Infectious events of special interest.

Supplementary Table S4 Number of patients experiencing adverse events of special interest after starting eculizumab therapy.

Funding: This work was funded by Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Conflicts of Interest: S. Muppidi has served as a paid consultant for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and Alexion Pharmaceuticals. K. Utsugisawa has served as a paid consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals. M. Benatar has received support from Eli Lilly and Company and has served as a paid consultant for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Ra Pharmaceuticals, Voyager Therapeutics, UCB Pharma, Denali Therapeutics, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Biogen, and Avexis and as a site investigator for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Cytokinetics, Neuraltus Pharmaceuticals, and Orphazyme. H. Murai has served as a paid consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals and has received speaker honoraria from Japan Blood Products Organization. R. J. Barohn has served as a consultant for NuFactor and Momenta Pharmaceuticals and receives research support from PTC Therapeutics, Ra Pharma, Orphazyme, and Sanofi Genzyme. I. Illa has served as a paid consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals and UCB Pharma. S. Jacob has served as a paid consultant for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and Alexion Pharmaceuticals. J. Vissing has received support from and/or served as a paid consultant for Sanofi/Genzyme and Santhera Pharmaceuticals and has served as a paid consultant for Sarepta Therapeutics, Audentes Therapeutics, NOVO Nordisk, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and Stealth Biotherapeutics. T. M. Burns has served as a paid consultant for Argenx and CSL Behring. J. T. Kissel has received support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, aTyr Pharma, Cytokinetics Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, BioMarin, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and AveXis. R. J. Nowak has received support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Grifols, and Ra Pharmaceuticals and has served as a paid consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Momenta, Ra Pharmaceuticals, Shire, and Grifols. H. Andersen has received research and travel support and speaker honoraria and has served as consultant for Octapharma, CSL Behring, NMD Pharma, Pfizer, Eisai, Sanofi Genzyme and UCB Pharma. C. Casasnovas has served as a paid consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Pharmanext, and CSL Behring. J. L. De Bleecker has served on the scientific advisory boards of Sanofi Genzyme and Pfizer and has received travel funding/speaker honoraria from Sanofi Genzyme and limited research funding from CSL Behring and CAF Belgium. T. H. Vu serves as a site principal investigator and on speaker bureaus for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, on speaker bureaus for CSL Behring, Allergan, and MT Pharma, and is the site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Ra Pharmaceuticals, Argenx, and UCB Pharmaceuticals. R. Mantegazza has received support from Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Bayer and BioMarin and has served as a paid consultant for BioMarin, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and Argenx BVBA. F. L. O'Brien and K. P. Fujita are employees of and own stock in Alexion Pharmaceuticals. J. J. Wang is a former employee of and owns stock in Alexion Pharmaceuticals. J. F. Howard Jr reports research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals; grants from Alexion Pharmaceuticals and UCB Pharma; honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals; and nonfinancial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Argenx, Ra Pharmaceuticals, and Toleranzia.

Contributor Information

Srikanth Muppidi, Email: muppidis@stanford.edu.

for the Regain Study Group:

Claudio Gabriel Mazia, Miguel Wilken, Fabio Barroso, Juliet Saba, Marcelo Rugiero, Mariela Bettini, Marcelo Chaves, Gonzalo Vidal, Alejandra Dalila Garcia, Guy Van den Abeele, Kathy de Koning, Katrien De Mey, Rudy Mercelis, Délphine Mahieu, Linda Wagemaekers, Philip Van Damme, Annelies Depreitere, Caroline Schotte, Charlotte Smetcoren, Olivier Stevens, Sien Van Daele, Nicolas Vandenbussche, Annelies Vanhee, Sarah Verjans, Jan Vynckier, Ann D'Hondt, Petra Tilkin, Alzira Alves de Siqueira Carvalho, Igor Dias Brockhausen, David Feder, Daniel Ambrosio, Pamela César, Ana Paula Melo, Renata Martins Ribeiro, Rosana Rocha, Bruno Bezerra Rosa, Thabata Veiga, Luiz Augusto da Silva, Murilo Santos Engel, Jordana Gonçalves Geraldo, Maria da Penha Ananias Morita, Erica Nogueira Coelho, Gabriel Paiva, Marina Pozo, Natalia Prando, Debora Dada Martineli Torres, Cristiani Fernanda Butinhao, Gustavo Duran, Tamires Cristina Gomes da Silva, Luiz Otavio Maia Gonçalves, Lucas Eduardo Pazetto, Tomás Augusto Suriane Fialho, Luciana Renata Cubas Volpe, Luciana Souza Duca, Maurício André Gheller Friedrich, Alexandre Guerreiro, Henrique Mohr, Maurer Pereira Martins, Daiane da Cruz Pacheco, Luciana Ferreira, Ana Paula Macagnan, Graziela Pinto, Aline de Cassia Santos, Acary Souza Bulle Oliveira, Ana Carolina Amaral Andrade, Marcelo Annes, Liene Duarte Silva, Valeria Cavalcante Lino, Wladimir Pinto, Natália Assis, Fernanda Carrara, Carolina Miranda, Iandra Souza, Patricia Fernandes, Zaeem Siddiqi, Cecile Phan, Jeffrey Narayan, Derrick Blackmore, Ashley Mallon, Rikki Roderus, Elizabeth Watt, Stanislav Vohanka, Josef Bednarik, Magda Chmelikova, Marek Cierny, Stanislava Toncrova, Jana Junkerova, Barbora Kurkova, Katarina Reguliova, Olga Zapletalova, Jiri Pitha, Iveta Novakova, Michaela Tyblova, Ivana Jurajdova, Marcela Wolfova, Thomas Harbo, Lotte Vinge, Susanne Krogh, Anita Mogensen, Joan Højgaard, Nanna Witting, Anne Ostergaard Autzen, Jane Pedersen, Juha-Pekka Eralinna, Mikko Laaksonen, Olli Oksaranta, Tuula Harrison, Jaana Eriksson, Csilla Rozsa, Melinda Horvath, Gabor Lovas, Judit Matolcsi, Gyorgyi Szabo, Gedeonne Jakab, Brigitta Szabadosne, Laszlo Vecsei, Livia Dezsi, Edina Varga, Monika Konyane, Giovanni Antonini, Antonella Di Pasquale, Matteo Garibaldi, Stefania Morino, Fernanda Troili, Laura Fionda, Allessandro Filla, Teresa Costabile, Enrico Marano, Francesco Saccà, Angiola Fasanaro, Angela Marsili, Giorgia Puorro, Carlo Antozzi, Silvia Bonanno, Giorgia Camera, Alberta Locatelli, Lorenzo Maggi, Maria Pasanisi, Angela Campanella, Amelia Evoli, Paolo Emilio Alboini, Valentina D'Amato, Raffaele Iorio, Maurizio Inghilleri, Laura Fionda, Vittorio Frasca, Elena Giacomelli, Maria Gori, Diego Lopergolo, Emanuela Onesti, Vittorio Frasca, Maria Gabriele, Akiyuki Uzawa, Tetsuya Kanai, Naoki Kawaguchi, Masahiro Mori, Yoko Kaneko, Akiko Kanzaki, Eri Kobayashi, Katsuhisa Masaki, Dai Matsuse, Takuya Matsushita, Taira Uehara, Misa Shimpo, Maki Jingu, Keiko Kikutake, Yumiko Nakamura, Yoshiko Sano, Yuriko Nagane, Ikuko Kamegamori, Tomoko Tsuda, Yuko Fujii, Kazumi Futono, Yukiko Ozawa, Aya Mizugami, Yuka Saito, Hidekazu Suzuki, Miyuki Morikawa, Makoto Samukawa, Sachiko Kamakura, Eriko Miyawaki, Hirokazu Shiraishi, Teiichiro Mitazaki, Masakatsu Motomura, Akihiro Mukaino, Shunsuke Yoshimura, Shizuka Asada, Seiko Yoshida, Shoko Amamoto, Tomomi Kobashikawa, Megumi Koga, Yasuko Maeda, Kazumi Takada, Mihoko Takada, Masako Tsurumaru, Yumi Yamashita, Yasushi Suzuki, Tetsuya Akiyama, Koichi Narikawa, Ohito Tano, Kenichi Tsukita, Rikako Kurihara, Fumie Meguro, Yusuke Fukuda, Miwako Sato, Meinoshin Okumura, Soichiro Funaka, Tomohiro Kawamura, Masayuki Makamori, Masanori Takahashi, Namie Taichi, Tomoya Hasuike, Eriko Higuchi, Hisako Kobayashi, Kaori Osakada, Tomihiro Imai, Emiko Tsuda, Shun Shimohama, Takashi Hayashi, Shin Hisahara, Jun Kawamata, Takashi Murahara, Masaki Saitoh, Shuichiro Suzuki, Daisuke Yamamoto, Yoko Ishiyama, Naoko Ishiyama, Mayuko Noshiro, Rumi Takeyama, Kaori Uwasa, Ikuko Yasuda, Anneke van der Kooi, Marianne de Visser, Tamar Gibson, Byung-Jo Kim, Chang Nyoung Lee, Yong Seo Koo, Hung Youl Seok, Hoo Nam Kang, HyeJin Ra, Byoung Joon Kim, Eun Bin Cho, MiSong Choi, HyeLim Lee, Ju-Hong Min, Jinmyoung Seok, JiEun Lee, Da Yoon Koh, JuYoung Kwon, SangAe Park, Eun Hwa Choi, Yoon-Ho Hong, So-Hyun Ahn, Dae Lim Koo, Jae-Sung Lim, Chae Won Shin, Ji Ye Hwang, Miri Kim, Seung Min Kim, Ha-Neul Jeong, JinWoo Jung, Yool-hee Kim, Hyung Seok Lee, Ha Young Shin, Eun Bi Hwang, Miju Shin, Maria Antonia Alberti Aguilo, Christian Homedes-Pedret, Natalia Julia Palacios, Laura Diez Porras, Valentina Velez Santamaria, Ana Lazaro, Exuperio Diez Tejedor, Pilar Gomez Salcedo, Mireya Fernandez-Fournier, Pedro Lopez Ruiz, Francisco Javier Rodriguez de Rivera, Maria Sastre, Josep Gamez, Pilar Sune, Maria Salvado, Gisela Gili, Gonzalo Mazuela, Elena Cortes Vicente, Jordi Diaz-Manera, Luis Antonio Querol Gutierrez, Ricardo Rojas Garcia, Nuria Vidal, Elisabet Arribas-Ibar, Fredrik Piehl, Albert Hietala, Lena Bjarbo, Ihsan Sengun, Arzu Meherremova, Pinar Ozcelik, Bengu Balkan, Celal Tuga, Muzeyyen Ugur, Sevim Erdem-Ozdamar, Can Ebru Bekircan‐Kurt, Nazire Pinar Acar, Ezgi Yilmaz, Yagmur Caliskan, Gulsah Orsel, Husnu Efendi, Seda Aydinlik, Hakan Cavus, Ayse Kutlu, Gulsar Becerikli, Cansu Semiz, Ozlem Tun, Murat Terzi, Baki Dogan, Musa Kazim Onar, Sedat Sen, Tugce Kirbas Cavdar, Adife Veske, Fiona Norwood, Aikaterini Dimitriou, Jakit Gollogly, Mohamed Mahdi-Rogers, Arshira Seddigh, Giannis Sokratous, Gal Maier, Faisal Sohail, Girija Sadalage, Pravin Torane, Claire Brown, Amna Shah, Sivakumar Sathasivam, Heike Arndt, Debbie Davies, Dave Watling, Anthony Amato, Thomas Cochrane, Mohammed Salajegheh, Kristen Roe, Katherine Amato, Shirli Toska, Gil Wolfe, Nicholas Silvestri, Kara Patrick, Karen Zakalik, Jonathan Katz, Robert Miller, Marguerite Engel, Dallas Forshew, Elena Bravver, Benjamin Brooks, Sarah Plevka, Maryanne Burdette, Scott Cunningham, Mohammad Sanjak, Megan Kramer, Joanne Nemeth, Clara Schommer, Scott Tierney, Vern Juel, Jeffrey Guptill, Lisa Hobson-Webb, Janice Massey, Kate Beck, Donna Carnes, John Loor, Amanda Anderson, Robert Pascuzzi, Cynthia Bodkin, John Kincaid, Riley Snook, Sandra Guingrich, Angela Micheels, Vinay Chaudhry, Andrea Corse, Betsy Mosmiller, Andrea Kelley, Doreen Ho, Jayashri Srinivasan, Michal Vytopil, Jordan Jara, Nicholas Ventura, Stephanie Scala, Cynthia Carter, Craig Donahue, Carol Herbert, Elaine Weiner, Sharmeen Alam, Jonathan McKinnon, Laura Haar, Naya McKinnon, Karan Alcon, Kaitlyn McKenna, Nadia Sattar, Kevin Daniels, Dennis Jeffery, Miriam Freimer, Joseph Chad Hoyle, Julie Agriesti, Sharon Chelnick, Louisa Mezache, Colleen Pineda, Filiz Muharrem, Chafic Karam, Julie Khoury, Tessa Marburger, Harpreet Kaur, Diana Dimitrova, James Gilchrist, Brajesh Agrawal, Mona Elsayed, Stephanie Kohlrus, Angela Andoin, Taylor Darnell, Laura Golden, Barbara Lokaitis, Jenna Seelback, Neelam Goyal, Sarada Sakamuri, Yuen T. So, Shirley Paulose, Sabrina Pol, Lesly Welsh, Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, Alejandro Tobon Gonzales, Lorraine Dishman, Floyd Jones, Anna Gonzalez, Patricia Padilla, Amy Saklad, Marcela Silva, Sharon Nations, Jaya Trivedi, Steve Hopkins, Mohamed Kazamel, Mohammad Alsharabati, Liang Lu, Kenkichi Nozaki, Sandi Mumfrey-Thomas, Amy Woodall, Tahseen Mozaffar, Tiyonnoh Cash, Namita Goyal, Gulmohor Roy, Veena Mathew, Fatima Maqsood, Brian Minton, H. James Jones, Jeffrey Rosenfeld, Rebekah Garcia, Laura Echevarria, Sonia Garcia, Michael Pulley, Shachie Aranke, Alan Ross Berger, Jaimin Shah, Yasmeen Shabbir, Lisa Smith, Mary Varghese, Laurie Gutmann, Ludwig Gutmann, Nivedita Jerath, Christopher Nance, Andrea Swenson, Heena Olalde, Nicole Kressin, Jeri Sieren, Mazen Dimachkie, Melanie Glenn, April McVey, Mamatha Pasnoor, Jeffery Statland, Yunxia Wang, Tina Liu, Kelley Emmons, Nicole Jenci, Jerry Locheke, Alex Fondaw, Kathryn Johns, Gabrielle Rico, Maureen Walsh, Laura Herbelin, Charlene Hafer-Macko, Justin Kwan, Lindsay Zilliox, Karen Callison, Valerie Young, Beth DiSanzo, Kerry Naunton, Martin Bilsker, Khema Sharma, Anne Cooley, Eliana Reyes, Sara-Claude Michon, Danielle Sheldon, Julie Steele, Chafic Karam, Manisha Chopra, Rebecca Traub, Lara Katzin, Terry McClain, Brittany Harvey, Adam Hart, Kristin Huynh, Said Beydoun, Amaiak Chilingaryan, Victor Doan, Brian Droker, Hui Gong, Sanaz Karimi, Frank Lin, Terry McClain, Krishna Pokala, Akshay Shah, Anh Tran, Salma Akhter, Ali Malekniazi, Rup Tandan, Michael Hehir, Waqar Waheed, Shannon Lucy, Michael Weiss, Jane Distad, Susan Strom, Sharon Downing, Bryan Kim, Tulio Bertorini, Thomas Arnold, Kendrick Hendersen, Rekha Pillai, Ye Liu, Lauren Wheeler, Jasmine Hewlett, Mollie Vanderhook, Daniel Dicapua, Benison Keung, Aditya Kumar, Huned Patwa, Kimberly Robeson, Irene Yang, Joan Nye, and Hong Vu

REFERENCES

- 1. Conti‐Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ. Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest 2006;116:2843–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Whittingham S, Duane DD. Antibody to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and diagnostic value. Neurology 1976;26:1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mantegazza R, Pareyson D, Baggi F, Romagnoli P, Peluchetti D, Sghirlanzoni A, et al Anti‐AChR antibody: relevance to diagnosis and clinical aspects of myasthenia gravis. Ital J Neurol Sci 1988;9:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vincent A, McConville J, Farrugia ME, Bowen J, Plested P, Tang T, et al Antibodies in myasthenia gravis and related disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;998:324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vincent A, Newsom‐Davis J. Acetylcholine receptor antibody as a diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis: results in 153 validated cases and 2967 diagnostic assays. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:1246–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oh SJ, Kim DE, Kuruoglu R, Bradley RJ, Dwyer D. Diagnostic sensitivity of the laboratory tests in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 1992;15:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Somnier FE. Clinical implementation of anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993;56:496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biesecker G, Gomez CM. Inhibition of acute passive transfer experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis with Fab antibody to complement C6. J Immunol 1989;142:2654–2659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christadoss P. C5 gene influences the development of murine myasthenia gravis. J Immunol 1988;140:2589–2592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karachunski PI, Ostlie NS, Monfardini C, Conti‐Fine BM. Absence of IFN‐γ or IL‐12 has different effects on experimental myasthenia gravis in C57BL/6 mice. J Immunol 2000;164:5236–5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piddlesden SJ, Jiang S, Levin JL, Vincent A, Morgan BP. Soluble complement receptor 1 (sCR1) protects against experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol 1996;71:173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fumagalli G, Engel AG, Lindstrom J. Ultrastructural aspects of acetylcholine receptor turnover at the normal end‐plate and in autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1982;41:567–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conti‐Tronconi B, Tzartos S, Lindstrom J. Monoclonal antibodies as probes of acetylcholine receptor structure. 2. Binding to native receptor. Biochemistry 1981;20:2181–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howard JF Jr., Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, Murai H, Barohn RJ, Illa I, et al Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody‐positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:976–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suh J, Goldstein JM, Nowak RJ. Clinical characteristics of refractory myasthenia gravis patients. Yale J Biol Med 2013;86:255–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buzzard KA, Meyer NJ, Hardy TA, Riminton DS, Reddel SW. Induction intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by maintenance oral immunosuppression in refractory myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2015;52:204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Silvestri NJ, Wolfe GI. Treatment‐refractory myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014;15:167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, Evoli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I, et al International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology 2016;87:419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howard JF Jr. Myasthenia gravis: the role of complement at the neuromuscular junction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018;1412:113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Engel‐Nitz NM, Boscoe AN, Wolbeck R, Johnson J, Silvestri NJ. Burden of illness in patients with treatment refractory myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2018;58:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jani‐Acsadi A, Lisak RP. Myasthenic crisis: guidelines for prevention and treatment. J Neurol Sci 2007;261:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rother RP, Rollins SA, Mojcik CF, Brodsky RA, Bell L. Discovery and development of the complement inhibitor eculizumab for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Nat Biotechnol 2007;25:1256–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, Hariri S, Fox L, MacNeil JR. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. Am J Transplant 2017;17:2481–2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, Foster B, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ. Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology 1999;52:1487–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barohn RJ, McIntire D, Herbelin L, Wolfe GI, Nations S, Bryan WW. Reliability testing of the quantitative myasthenia gravis score. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998;841:769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burns TM, Conaway M, Sanders DB; MG‐Qol Study Group . The MG Composite: a valid and reliable outcome measure for myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2010;74:1434–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burns TM, Grouse CK, Conaway MR, Sanders DB; MG‐QOL15 Study Group. Construct and concurrent validation of the MG‐QOL15 in the practice setting. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muppidi S. The myasthenia gravis–specific activities of daily living profile. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1274:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katzberg HD, Barnett C, Merkies IS, Bril V. Minimal clinically important difference in myasthenia gravis: outcomes from a randomized trial. Muscle Nerve 2014;49:661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muppidi S, Wolfe GI, Conaway M, Burns TM, the MG Composite and MG‐QOL15 Study Group. MG‐ADL: still a relevant outcome measure. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:727–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jaretzki A 3rd, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM, Kaminski HJ, Keesey JC, Penn AS, et al Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology 2000;55:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, Brodsky RA, Socie G, Muus P, et al The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1233–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zuber J, Fakhouri F, Roumenina LT, Loirat C, Fremeaux‐Bacchi V, French Study Group for a HCG . Use of eculizumab for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathies. Nat Rev Nephrol 2012;8:643–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zuber J, Le Quintrec M, Krid S, Bertoye C, Gueutin V, Lahoche A, et al Eculizumab for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome recurrence in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 2012;12:3337–3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gajdos P, Tranchant C, Clair B, Bolgert F, Eymard B, Stojkovic T, et al Treatment of myasthenia gravis exacerbation with intravenous immunoglobulin: a randomized double‐blind clinical trial. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1689–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou Y, Gong B, Lin F, Rother RP, Medof ME, Kaminski HJ. Anti‐C5 antibody treatment ameliorates weakness in experimentally acquired myasthenia gravis. J Immunol 2007;179:8562–8567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kusner LL, Satija N, Cheng G, Kaminski HJ. Targeting therapy to the neuromuscular junction: proof of concept. Muscle Nerve 2014;49:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huda R, Tuzun E, Christadoss P. Complement C2 siRNA mediated therapy of myasthenia gravis in mice. J Autoimmun 2013;42:94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1 Patients who discontinued from open‐label extension study.

Supplementary Table S2 All serious adverse events.

Supplementary Table S3 Infectious events of special interest.

Supplementary Table S4 Number of patients experiencing adverse events of special interest after starting eculizumab therapy.