Abstract

Invertebrate studies have highlighted a role for EH and SH3 domain Intersectin (Itsn) proteins in synaptic vesicle recycling and morphology. Mammals have two Itsn genes (Itsn1 and Itsn2), both of which can undergo alternative splicing to include DBL/PH and C2 domains not present in invertebrate Itsn proteins. To probe for specific and redundant functions of vertebrate Itsn genes, we generated Itsn1, Itsn2, and double mutant mice. While invertebrate mutants showed severe synaptic abnormalities, basal synaptic transmission and plasticity were unaffected at Schaffer CA1 synapses in mutant mice. Surprisingly, intercortical tracts—corpus callosum, ventral hippocampal, and anterior commissures—failed to cross the midline in mice lacking Itsn1, but not Itsn2. In contrast, tracts extending within hemispheres and those that decussate to more caudal brain segments appeared normal. Itsn1 mutant mice showed severe deficits in Morris water maze and contextual fear memory tasks, whereas mice lacking Itsn2 showed normal learning and memory. Thus, coincident with the acquisition of additional signaling domains, vertebrate Itsn1 has been functionally repurposed to also facilitate interhemispheric connectivity essential for high order cognitive functions.

Introduction

The evolutionarily conserved Intersectins (Itsns) contain multiple protein-protein interacting surfaces—two Eps15 homologous (EH) domains, a coiled-coil domain and five SH3 domains—as well as vertebrate-specific DBL/PH and C2 domains. Invertebrates have one Itsn gene while mammals have two, Itsn1 and Itsn2. Each mammalian Itsn gene is expressed as short (Itsn1S, Itsn2S) or long (Itsn1L, Itsn2L) variants through alternative splicing (Guipponi et al., 1998; Yamabhai et al., 1998; Sengar et al., 1999) (Fig. 1A). Itsn1S, Itsn2S, and Itsn2L proteins are widely expressed throughout the body, whereas Itsn1L expression is restricted to the nervous system (Guipponi et al., 1998; Sengar et al., 1999; Pucharcos et al., 2001).

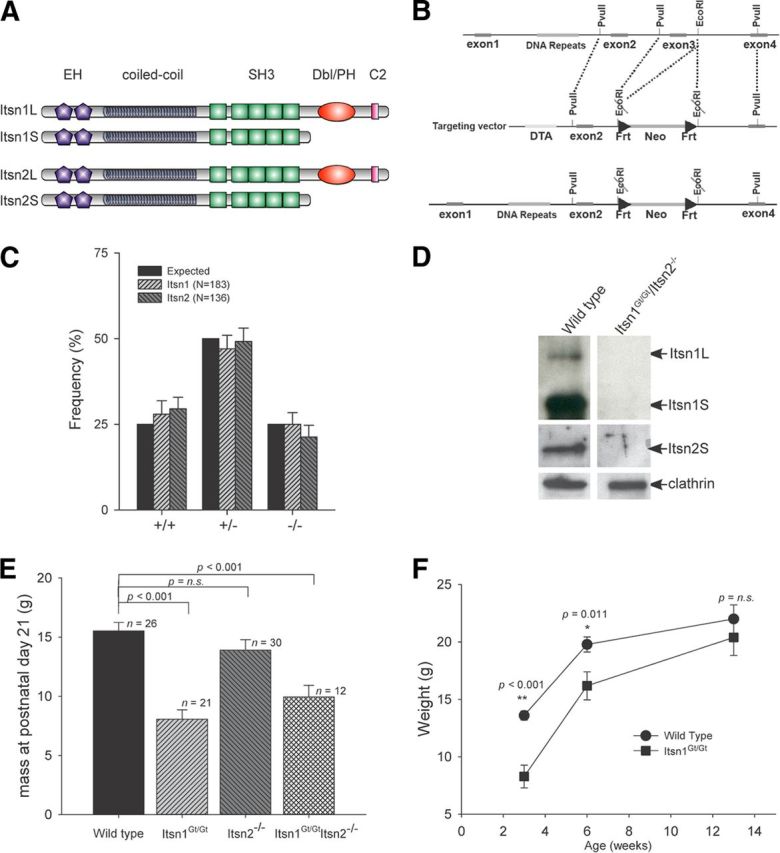

Figure 1.

Gross phenotypic characteristics of Itsn mutations. A, Schematic representation of protein domains in major Itsn1 and Itsn2 isoforms. Each gene produces two proteins. Two EH, a coiled coil, and five SH3 domains are common to each. A Cdc42 GEF and C2 domain are specific to each long form. B, Targeting strategy for generation of Itsn2−/− mice. Exon3 was deleted resulting in a frame shift mutation. C, Offspring from breeding heterozygous mutant pairs were born at the expected Mendelian frequency. D, Western blots of whole brain lysates from double mutant mice were compared with wild-type littermates. Double mutant mice lacked expression of Itsn isoforms in the brain. E, Body mass at time of weaning (3 weeks of age). Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− mice had significantly lower body mass versus WT littermates. Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− mice were not significantly different from each other (p = 0.201). F, Itsn1Gt/Gt mice have comparable body mass to WT littermates by 13 weeks of age. p values were determined using one-way ANOVA (Holm–Sidak method).

Itsns have been studied in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans. In Drosophila, Itsn mutants show reduced accumulation of endocytic proteins Eps15, AP180, and Dynamin, as well as impaired synaptic vesicle recycling at the neuromuscular junction (Koh et al., 2004; Marie et al., 2004; O'Connor-Giles et al., 2008; Rodal et al., 2008). The loss of D-Itsn ultimately results in catastrophic synaptic overgrowth and lethality in third instar larvae. C. elegans Itsn also functions to facilitate efficient synaptic vesicle recycling (Rose et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Despite significant homology between worm and fly proteins, C. elegans mutants are viable (Glodowski et al., 2007; Rose et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008).

Itsn gene function is less defined in vertebrates. A number of in vitro and ex vivo studies have revealed functions for mammalian Itsns. For example, in cell culture, Itsn proteins have been implicated in endocytosis, exocytosis, dendritic spine maturation, neurite extension, apoptosis, as well as regulation of cell polarity, actin remodeling, and mitogenic signaling (for review, see Pechstein et al., 2010; Sengar et al., 2012). Recently, Yu et al. (2008) have generated and studied Itsn1 mutant mice. Most of these were grossly normal but exocytic and endocytic defects were observed in ex vivo cultures. Itsn2 mutant mice have yet to be described. Here we report on genetic analysis of the mammalian Itsn gene family and identify an essential and novel role for Itsn1 in axonal growth at the cortical midline as well as in spatial learning.

Materials and Methods

Intersectin mice.

Itsn1+/Gt ES cells were purchased from the German Gene Trap Consortium (GGTC) (Wiles et al., 2000). Itsn2+/− ES cells were generated by homologous recombination (Fig. 1B). Both ES cell lines were implanted into recipient surrogate mice using aggregation techniques and backcrossed to 129Sv mice for 10 generations. Note: Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn2−/− mice represent complete loss-of-function mutants. For Itsn1Gt/Gt, this is based on deletion of the last four SH3 domains, deletion of Itsn1L-specific exons, and loss of Itsn1 expression on Western blots (Fig. 1D). For Itsn2−/−, this is based on deletion of exon3 resulting in a frameshift mutation early in the coding sequence, as well as lack of Itsn2 protein by Western blot (Fig. 1D). Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− double mutants were generated by interbreeding Itsn1+/GtItsn2−/− males and females. Alleles were identified by PCR using the following primer sets: Itsn1Gt/+, ATCACACTCAGTCTTCGCTAGCTG, CCCTACTTGCCTTGGTCTTTGCTT, and CGCCTTATCCGGTAACTATCGTCT; Itsn2+/−, TGCTGGAGTTAAGTCAGCAC, and AGCAAGGAAAGGGATAGCAC. Animals of both sexes were used for these experiments.

For behavioral experiments, mice were individually handled (2 min) for each of 10 d before testing. Mice had ad libitum access to rodent chow and water in a 12 h dark/light cycle room. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with requirements of the Province of Ontario Animals for Research Act, 1971 and the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC 1984, 1995).

Growth cone fluorescent cytochemistry.

Primary hippocampal neurons were prepared from fetal Wistar rats (embryonic day 17–19). These were plated on poly-d-lysine treated glass coverslips (as previously described) (Salter and Hicks, 1994). At 3 DIV, cells were fixed with 4% PFA and blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100/5% donkey serum in PBS for 60 min. Cells were incubated with anti-Itsn1 mAb (BD Biosciences; 1:100) in 0.05% Triton X-100/1% donkey serum in PBS overnight at 4°C. After three washes with PBS, Cy3-phalloidin (Invitrogen) and Cy5-anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunology; 1:500) in 0.05% Triton X-100/1% donkey serum were added for 60 min followed by three washes with PBS before mounting on slides. Images were taken using spinning disk confocal microscopy. Relative fluorescent intensity was measured and normalized to phalloidin-stained regions within boxed regions as a function of the square area.

Magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging.

Initially, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and intracardially perfused with 30 ml of 0.1 m PBS containing 10 U/ml heparin (Sigma) and 2 mm ProHance (a Gadolinium contrast agent) followed by 30 ml of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) containing 2 mm ProHance (Spring et al., 2007). Perfusions were performed with a Pharmacia minipump at a rate of ∼100 ml/h. After perfusion, mice were decapitated and the skin, lower jaw, ears, and cartilaginous nose tip were removed. The brain and remaining skull structures were incubated in 4% PFA + 2 mm ProHance overnight at 4°C and then transferred to 0.1 m PBS containing 2 mm ProHance and 0.02% sodium azide for at least 7 d before MRI scanning.

A multi-channel 7.0 tesla MRI scanner (Varian) with a 6 cm inner bore diameter insert gradient set (max gradient strength 100 G/cm, rise time = 150 μs) was used for all images of brains within skulls. Three custom-built solenoid coils were used to image three brains in parallel (Bock et al., 2005).

For volume changes, conventional MRI scan parameters were used: a T2-weighted, 3-D fast spin-echo sequence, with a TR of 325 ms, and TEs of 10 ms per echo for 6 echoes, four averages, field-of-view of 14 × 14 × 25 mm3, and matrix size = 432 × 432 × 780 giving an image with 0.032 mm isotropic voxels. Total imaging time was ∼11 h (Lerch et al., 2011).

For diffusion experiments, a 3-D diffusion weighted fast spin-echo sequence with an echo train length of 6 was used with a TR of 325 ms, first TE of 30 ms, and a TE of 6 ms for the remaining 5 echos, 10 averages, field-of-view 14 × 14 × 25 mm3, and a matrix size of 120 × 120 × 214 yielding an image with 0.117 mm isotropic voxels. One b = 0 s/mm2 image (with minimal diffusion weighting) and six high b-value images (b = 1956 s/mm2) in six different directions [(1,1,0),(1,0,1),(0,1,1),(−1,1,0),(−1,0,1),(0,1,−1)] (Gx,Gy,Gz) were acquired. Total imaging time was ∼16 h.

To visualize and compare any changes, mouse brain images were linearly (6 parameter followed by a 12 parameter) and nonlinearly registered toward a pre-existing atlas and transform was created for each mouse (Dorr et al., 2008). All scans were then resampled with the appropriate transform and averaged to create a population atlas representing the average anatomy of the study sample. All registrations were performed using mni_autoreg tools (Collins et al., 1994). The result of registration was to have all scans deformed into exact alignment with each other in an unbiased fashion. This allowed for analysis of deformations needed to take each individual mouse's anatomy into this final atlas space, the goal being to model how deformation fields related to genotype (Nieman et al., 2006; Lerch et al., 2008). Determinants of deformation fields were then calculated as measures of volume at each voxel. Significant volume and shape changes could then be calculated by warping a pre-existing classified MRI atlas onto the population atlas (Dorr et al., 2008), which allowed for a volume of 62 segmented structures encompassing cortical lobes, large white matter structures (i.e., corpus callosum), ventricles, cerebellum, brain stem, and olfactory bulbs (Dorr et al., 2008) to be assessed in each brain. Multiple comparisons were controlled for by using false discovery rate (FDR) (Genovese et al., 2002).

Fiber tractography was performed on images using DTI studio (DTI studio software, H. Jiang and S. Mori, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Fiber tracking was initiated in bilateral regions of interest and was terminated if the fractional anisotropy (FA) dropped below 0.35 or the tract turning angle was larger than 70°.

Open field.

For the open field test, each mouse was placed in the center of an empty white plastic chamber (46 × 46 × 20 cm) and observed for 30 min. Mouse location was tracked by a camera located above the open field, and total distance traveled as well as time spent in three different zones (outer, middle, inner) measured by camera linked to a computer system using LimeLight software (Coulbourn Instruments).

Cued-MWM.

Mice were trained to swim to a cued platform in a pool of opaque water for 5 d. A red cylindrical object was placed 7 cm above the 5 cm radius platform, which was submerged 1 cm below the water surface. A total of six trials were performed on each training day. At the start of training, a mouse was placed on the platform for 15 s and then dropped into the pool with its nose facing the wall at various quadrants of the pool (north, east, south, west). The mouse was then given 1 min to swim to the cued platform. Once it had reached the platform, it remained there for 15 s before the start of the next trial. On the probe test day (day 6), the mouse was placed on the platform for 15 s after which the platform and cue were removed from the pool and the mouse given 1 min to locate the platform. Performance during the probe test was analyzed by comparing the percentage of time spent in the area of the pool that previously contained the cued platform (target zone; 20 cm radius around the platform area) as compared with the opposite or all other zones. The distance traveled, time to platform, and swim speed during training days were measured using ActiMetrics WaterMaze software.

Fear conditioning.

Mice were trained to associate a mild foot shock with the context where training was conducted. During the 3.5 min training session, each mouse was placed in a chamber and given 2 min to habituate to the environment. A mild foot shock of 0.7 mA intensity was delivered and the mouse was taken out of the chamber 1 min later. Successful delivery of a foot shock was assessed via video observation of each mouse. Twenty-four hours after training, mice were returned into the training context and the percentage of time spent freezing was assessed over a 5 min period. Shock was delivered via the MED-PC IV program and ActiMetrics Freeze Frame, a video motion detection tracking system used to detect minute movements during training and testing sessions.

Fine motor test.

The grid test assesses the fine motor ability of mice to maneuver on a 2 cm × 2 cm grid. The mouse was placed at the center of a grid 20 cm above a table and given 5 min to move around. Each session was video recorded and then watched in slow motion to count the number of times a forepaw or hindpaw slipped through the grid. If two paws slipped at the same time, it was scored as two slips. Two scorers, blind to mouse genotype, observed motor testing.

Electrophysiology.

Hippocampal slices (300 μm) were prepared from adult mice using conventional techniques. Before recording, slices were incubated in a holding chamber for >1 h in oxygenated artificial CSF (ACSF) containing 132 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 2 mm MgCl2, 11 mm d-glucose, 24 mm NaHCO3, and 2 mm CaCl2. A single slice was then transferred to the recording chamber and superfused with ACSF supplemented with 5 μm 1(S),9(R)-(-)-Bicuculline methylbromide at 2 ml/min. When indicated, 100 μm d(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid was also added in perfusion. fEPSPs from the CA1 stratum radiatum region were recorded with glass micropipettes filled with ACSF and evoked by stimulating Schaffer collateral afferents using bipolar concentric tungsten electrodes. The afferent fibers were stimulated at 0.05 Hz with single pulses at an intensity that produced 30–35% of maximum synaptic response. LTP was induced by theta-burst stimulation (TBS) consisting of 15 bursts of 4 pulses at 100 Hz with an interburst interval of 200 ms or titanic stimulation consisting of 2 trains of 100 Hz pulses lasting for 500 ms with an intertrain interval of 20 s. In some experiments, 10 repeated stimuli at different frequency (5, 10, 20, or 50 Hz) were delivered to examine the presynaptic release efficiency with 100 μm d(-)-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid in perfusion to prevent any NMDA receptor-dependent postsynaptic plasticity. fEPSP slope was calculated as the slope of 10–60% of the rising phase of the peak. Raw data were acquired with a MultiClamp 700A amplifier and a Digidata 1322A acquisition system (Molecular Devices) sampled at 10 Hz. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate statistical significance.

Results

Itsn1 and/or Itsn2 mutant mice are viable

To define nonredundant functions of Itsns (Fig. 1A), we generated Itsn1 mutant mice from a gene-trap (referred herein as Gt) embryonic stem cell line (Wiles et al., 2000) and Itsn2 mice through targeted deletion of exon 3 (Fig. 1B). Itsn1+/Gt × Itsn1+/Gt and Itsn2+/− × Itsn2+/− heterozygous crosses produced homozygous Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn2−/− offspring at the expected frequency (Fig. 1C). Double mutant mice produced by intercrossing single mutants were also viable. Brain homogenates from Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− lacked Itsn protein expression (Fig. 1D). At 3 weeks of age, Itsn1Gt/Gt mice were noticeably smaller than their wild-type (WT) littermates (Fig. 1E) and ∼10% of Itsn1Gt/Gt mice failed to thrive. The average weight of Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− mice was indistinguishable from Itsn1Gt/Gt mice (Fig. 1E). Although Itsn1 mutants were smaller at weaning, their weight recovered by 3 months of age (Fig. 1F). This is consistent with results from Yu et al. (2008), who reported that a small fraction of Itsn1−/− (Itsn1-TK) mice died before weaning. Indeed, the viability and slow growth phenotype observed in both cases confirms the status of Itsn1Gt/Gt as a complete loss of function allele. Brains of Itsn1Gt/Gt mice were smaller as a percentage of body mass than those of WT mice (1.72 ± 0.08%, n = 7, versus 1.95 ± 0.09%, n = 6, respectively). Itsn2−/− mutant brains were not different than WT mouse brains (1.96 ± 0.11%, n = 7). Thus, neither Itsn1 nor Itsn2 is required for survival, but in the case of Itsn1 mutant mice, early weight gain and overall brain size were affected.

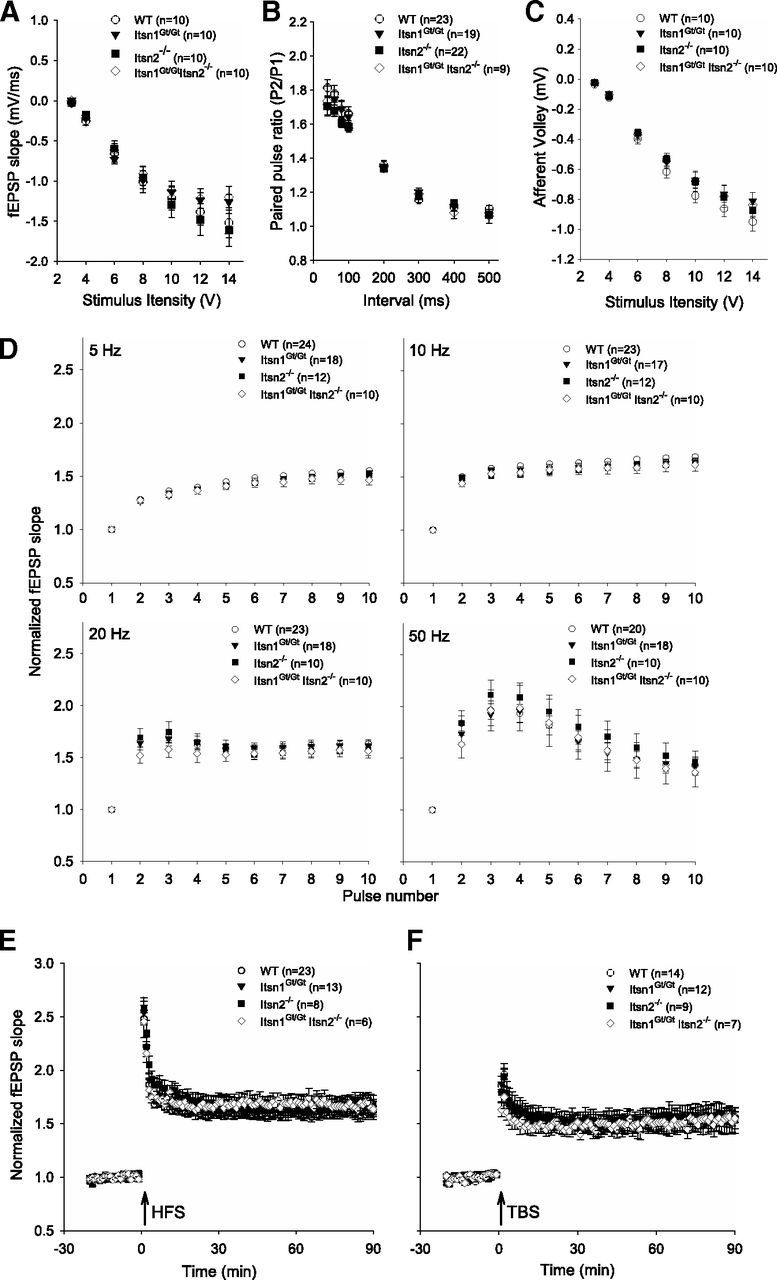

Itsn1 mutants show normal hippocampal synaptic transmission and plasticity

Mutation of Itsn in invertebrates results in altered synaptic transmission (Koh et al., 2004; Marie et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008). To assess whether this is the case in mice, we examined synaptic transmission and plasticity in the CA1 hippocampus. We recorded field EPSPs (fEPSPs) at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses in acute hippocampal slices from adult mice of each genotype. Across a series of stimulation intensities, average fEPSP slopes in ItsnGt/Gt, Itsn2−/−, and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− slices were not different from those in WT slices (Fig. 2A). Likewise, there were no differences in afferent volley (Fig. 2B), which together with the lack of difference in input–output relationship indicate that basal synaptic transmission was unaffected by loss of Itsn1 and/or Itsn2. Paired-pulse facilitation was also comparable in slices from each genotype (Fig. 2C) indicative of normal presynaptic function. To examine the fidelity of synaptic transmission across a range of stimulation frequencies, we measured fEPSP slope at frequencies of 5, 10, 20, or 50 Hz. We found no differences in response at any frequency in WT, ItsnGt/Gt, Itsn2−/−, or Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− mice (Fig. 2D). Finally, we investigated long-term potentiation (LTP) induced by either tetanic or theta burst stimulation protocols. Robust LTP was induced by either protocol with no differences in magnitude across genotypes (Fig. 2E,F). Thus, disruption of Itsn1 and/or Itsn2 does not affect basal synaptic transmission, or short- or long-term plasticity at Schaffer collateral synapses in the hippocampus.

Figure 2.

Basal synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation at SC-CA1 synapses are normal in Itsn mutants. A–C, Measurements of fEPSPs, afferent volleys, and paired pulse ratios in all genotypes revealed no significant differences in hippocampal basal synaptic physiology. D, Normalized fEPSPs during increasing stimulation frequency were indistinguishable between genotypes. E, F, Induction of LTP using HFS and TBS stimulation of SC-CA1 synapses were indistinguishable between genotypes.

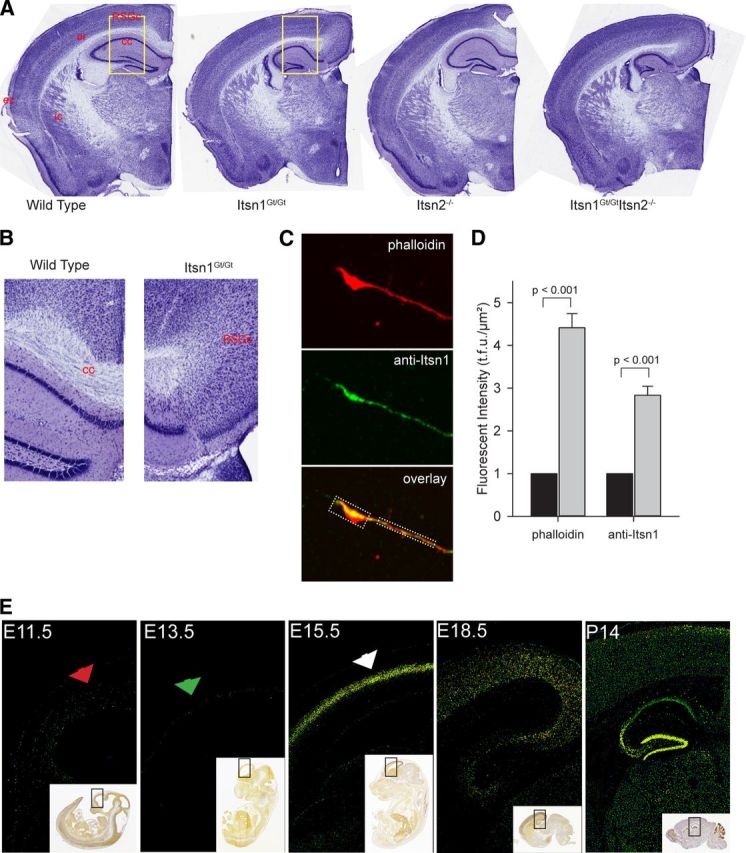

Lack of midline corpus callosum in Itsn1Gt/Gt mice

As synaptic transmission appeared normal in Itsn mutant mice, we next tested for abnormalities in brain structure. Indeed, the midline corpus callosum, a neocortical structure easily seen in coronal sections, was absent in mice lacking Itsn1 (Fig. 3A). External capsule fibers of Itsn1 mutant mice were bundled together and present across the oriens of the dorsal hippocampus. However, at the point where they should meet the corpus callosum, commissural fiber tracts failed to cross the medial longitudinal fissure (Fig. 3A). Rather, the white matter tract ended ipsilaterally at the level of the cortical gray matter (retrosplenial granule cortex c), which was extended beyond its normal boundary (Fig. 3B). In mice lacking Itsn2 alone, the corpus callosum was indistinguishable from the same structure in WT mice. As in Itsn1Gt/Gt mice, the midline corpus callosum was absent in Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− double mutants. Since callosal axons were primarily affected by loss of Itsn1 gene function, we asked if Itsn1 was present in axonal growth cones. Indeed, greater accumulation of Itsn1 was apparent in growth cones than axons of cultured neurons (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Disruption of Itsn1 results in corpus callosal agenesis. A, Cresyl violet staining of coronal sections of right-side brain hemispheres from representative WT and Itsn mutant mice (ec, external capsule; ic, internal capsule; or, oriens; cc, corpus callosum; RSGc, retrosplenial granule cortex c). B, Increased magnification of insets shown in yellow boxes in A. The corpus callosum ends in a probst-like bundle. C, Representative confocal image of growth cone from 3 DIV neuronal cultures. Phalloidin labels actin and dotted box regions indicate measured growth cone and axonal regions. D, A total of 29 cultured cells were imaged and both phalloidin and anti-Itsn1 fluorescent units were quantified in growth cones (gray bars) and normalized respectively to axonal levels (black bars). E, Embryonic expression of Itsn1 in cortical plate is detected at E15.5. Comparison of Itsn1 expression in cortical sections of the E11.5, E13.5, E15.5, E18.5, and P14 mouse brain. Fluorescent in situ hybridization using an Itsn1-specific probe revealed no detectable Itsn1 expression at E11.5 and E13.5. Itsn1 expression is detectable by E15.5 and remains on at E18.5. Postnatal brain shows strong Itsn1 expression in the hippocampus. Area surround by a black box in the inset shows region used in magnification. All sections and expression data were provided by the Allen Institute for Brain Science.

The hippocampus and corpus callosum share a common origin from developing cortical plate neurons in the subventricular zone (Aboitiz and Montiel, 2003; Mihrshahi, 2006). Itsn1 mRNA is highly and selectively expressed in the developing cortical plate at E15.5 but not at E11.5 or E13.5 (Fig. 1E; data from Allen Brain Atlas). Itsn1 expression remains on during subsequent embryonic and postnatal development (Fig. 3E). Axons of the corpus callosum extend to the midline at approximately embryonic day 16 in the mouse (Ozaki and Wahlsten, 1992). Thus, expression of Itsn1 is precisely timed to switch on when corpus callosal axons approach the midline.

Itsn1 mutants show a fiber tract deficiency in regions that cross the medial longitudinal fissure

The absence of a corpus callosum in Itsn1 mutants prompted us to ask whether development of other brain structures might require Itsn1 and/or Itsn2. We therefore performed an unbiased search of 30 distinct brain regions using high resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to look for structural differences among all four genotypes. By comparing brain region volumes, we found differences from WT only in mice mutant for Itsn1. Itsn2−/− brains were indistinguishable from those in WT animals (Table 1). In Itsn1Gt/Gt mice, 12 regions were small. Half of these were composed of subcortical gray matter while the remaining half were white matter.

Table 1.

Volume changes

| Region | Absolute volume (mean ±SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (n = 10) | Itsn1Gt/Gt (n = 14) | Itsn2−/− (n = 15) | Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− (n = 3) | |

| Amygdala | 12.70 ± 1.13 | 12.90 ± 0.57 | 12.64 ± 1.42 | 11.72 ± 0.47 |

| Anterior commissure—Pars anterior | 1.64 ± 0.25 | 1.19 ± 0.14** | 1.67 ± 0.16 | 0.99 ± 0.03** |

| Anterior commissure—Pars posterior | 0.51 ± 0.09 | 0.35 ± 0.06** | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.02** |

| Arbor vita of the cerebellum | 13.25 ± 0.94 | 12.82 ± 1.56 | 12.66 ± 1.35 | 12.51 ± 0.93 |

| Cerebellar cortex | 53.04 ± 4.18 | 53.59 ± 3.32 | 50.90 ± 6.19 | 50.07 ± 2.89 |

| Cerebellar peduncle—Inferior | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.16 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.87 ± 0.17 |

| Cerebellar peduncle—Middle | 1.45 ± 0.11 | 1.47 ± 0.19 | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 1.38 ± 0.10 |

| Cerebellar peduncle—Superior | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 0.99 ± 0.10 | 0.94 ± 0.07 |

| Cerebral cortex—Entorhinal cortex | 7.84 ± 0.81 | 7.76 ± 0.38 | 7.34 ± 1.06 | 6.92 ± 0.58 |

| Cerebral cortex—Frontal lobe | 38.30 ± 5.92 | 39.18 ± 1.95 | 38.36 ± 3.70 | 35.83 ± 2.11 |

| Cerebral cortex—Occipital lobe | 4.89 ± 0.56 | 4.99 ± 0.34 | 4.66 ± 0.55 | 4.73 ± 0.25 |

| Cerebral cortex—Parietotemporal lobe | 67.05 ± 7.51 | 65.01 ± 2.29 | 66.13 ± 6.45 | 59.42 ± 3.09 |

| Cerebral peduncle | 2.37 ± 0.17 | 1.97 ± 0.22 * | 2.38 ± 0.23 | 1.96 ± 0.19 * |

| Colliculus—Inferior | 5.18 ± 0.32 | 4.37 ± 0.35 ** | 5.18 ± 0.43 | 3.89 ± 0.26 ** |

| Colliculus—Superior | 8.04 ± 0.98 | 6.62 ± 0.50 ** | 7.90 ± 0.77 | 5.99 ± 0.22 ** |

| Corpus callosum | 18.84 ± 2.42 | 15.96 ± 1.24 ** | 19.56 ± 1.84 | 14.46 ± 0.95 ** |

| Fimbria | 3.35 ± 0.62 | 2.57 ± 0.20 ** | 3.43 ± 0.38 | 2.42 ± 0.17 ** |

| Fornix | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 0.92 ± 0.12 |

| Globus pallidus | 2.60 ± 0.39 | 2.14 ± 0.19 * | 2.64 ± 0.24 | 2.02 ± 0.15 * |

| Hippocampus | 19.59 ± 2.35 | 18.31 ± 0.90 | 18.75 ± 1.64 | 16.86 ± 0.72 * |

| Hypothalamus | 9.56 ± 0.85 | 9.97 ± 0.59 | 9.52 ± 0.98 | 9.32 ± 0.39 |

| Internal capsule | 2.98 ± 0.42 | 2.64 ± 0.31 | 3.04 ± 0.30 | 2.44 ± 0.12 * |

| Medulla | 25.71 ± 1.77 | 24.63 ± 2.34 | 23.95 ± 2.84 | 24.44 ± 2.95 |

| Midbrain | 13.15 ± 1.07 | 11.41 ± 0.80 ** | 12.97 ± 1.10 | 10.65 ± 0.29 ** |

| Olfactory bulbs | 26.13 ± 2.75 | 22.78 ± 1.66 ** | 25.90 ± 2.47 | 19.60 ± 0.38 ** |

| Optic tract | 1.78 ± 0.17 | 1.54 ± 0.18 * | 1.75 ± 0.17 | 1.44 ± 0.13 * |

| Pons | 16.99 ± 1.06 | 16.16 ± 1.27 | 16.49 ± 1.43 | 15.53 ± 0.45 |

| Posterior commissure | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| Striatum | 18.82 ± 3.42 | 16.28 ± 0.75 * | 19.26 ± 1.92 | 13.67 ± 0.30 ** |

| Thalamus | 15.34 ± 2.23 | 14.44 ± 0.47 | 15.75 ± 1.32 | 12.82 ± 0.34 * |

The absolute volume measurements in mm3 for each region of interest.

* indicates significance based on an FDR of <0.05 or ** <0.01 with respect to wild type.

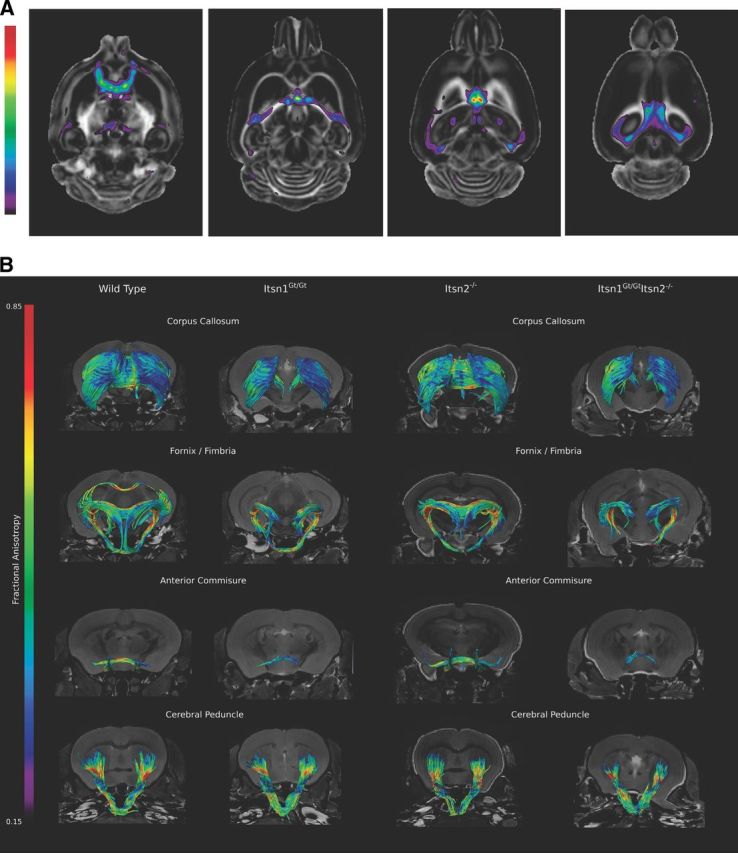

The observed defects in corpus callosum and volume reductions in other white matter regions raise the possibility that Itsn1 may play a role in connectivity within the brain. To search for such abnormalities we used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (Basser et al., 1994), which maps FA. FA reports the degree of restriction on diffusion of water in an underlying microstructure (termed anisotropy). For example, a high FA means a tissue is highly oriented (white matter) such that water molecules can only move along a restricted path as in an axon. Alternatively, a low FA means a tissue has no specific orientation (gray matter). Thus, a decrease in FA within a white matter tract typically indicates a loss of fiber bundle integrity. Comparison of FA maps by genotype revealed that Itsn1 mutant-specific differences located primarily near or at the midline (Fig. 4A). The largest FA differences between Itsn1Gt/Gt and WT brains were found in the corpus callosum, anterior commissure, fornix/fimbria, habenular commissure and, to a lesser degree, the superior cerebellar peduncle (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Cortical axonal tracts are disrupted in brains of Itsn1 mutants. A, FA analysis of Itsn1Gt/Gt brain. Differences in FA between WT and Itsn1Gt/Gt are localized to midline crossing structures. These differences are highlighted when overlapped onto the WT FA map. A higher t-statistic (closer to red) means a greater difference between WT and Itsn1Gt/Gt FA values for a given voxel. Shown are representative transverse sections from dorsal to ventral brain (left to right). The highest statistical differences are observed along tracts that approach the longitudinal medial fissure. B, Representative white matter tracts from each genotype show loss of tract structure around the midline in crossing fibers from mutants of Itsn1. Significant loss of order can be seen in Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− corpus callosum, ventral hippocampal commissure (white arrowhead) in the fornix/fimbria, and anterior commissures. Cerebral peduncles are indistinguishable between genotypes. Since tractography maps are calculated within established constants (see Materials and Methods), in some cases adjacent neuroanatomical tracts are visualized. For example, a piece of the corpus callosum is visible in the WT image of the fornix/fimbria as are tracts extending to the brain stem ventral and caudal to the fornix.

Table 2.

FA changes

| White matter regions | Fractional anisotropy |

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type (n = 8) | Itsn1Gt/Gt (n = 10) | |

| Anterior commissure—Pars anterior | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.03** |

| Anterior commissure—Pars posterior | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.03** |

| Arbor vita of the cerebellum | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.03 |

| Cerebellar peduncle—Inferior | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.03 |

| Cerebellar peduncle—Middle | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.88 ± 0.05 |

| Cerebellar peduncle—Superior | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.02** |

| Cerebral peduncle | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.03 |

| Corpus callosum | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.02** |

| Cortical spinal tract | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 0.66 ± 0.03 |

| Fasciculus retroflexus | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.02* |

| Fimbria | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.72 ± 0.02** |

| Fornix | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.03** |

| Habenular commissure | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.03** |

| Internal capsule | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.79 ± 0.02* |

| Lateral olfactory tract | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 0.59 ± 0.04 |

| Mammilothalamic tract | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.02 |

| Medical lemniscus/Medial longitudinal fasciculus | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.02 |

| Optic tract | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.75 ± 0.03* |

| Posterior commissure | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.02 |

The mean FA values for each region of interest.

* indicates significance based on an FDR of <0.05 or ** <0.01 with respect to wild type.

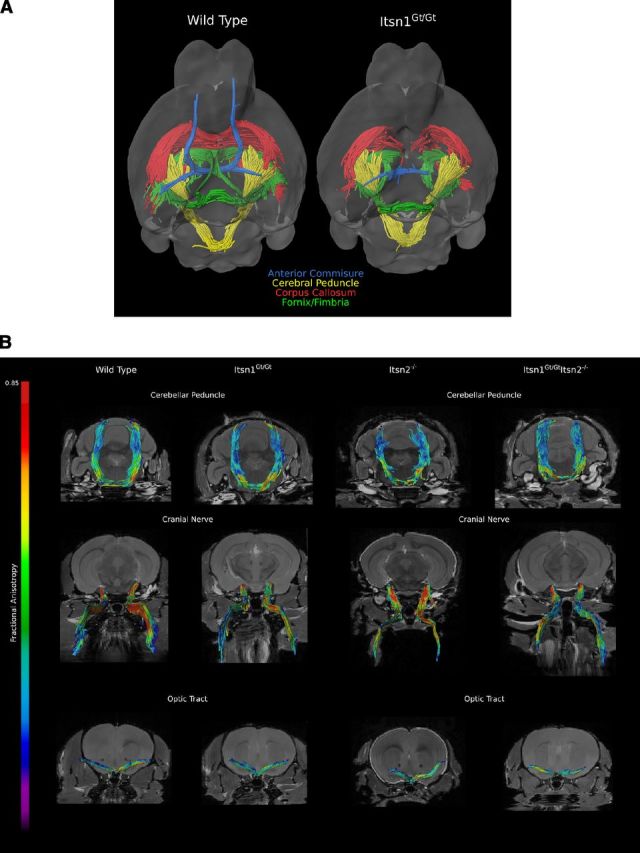

Next, using DTI data, we generated tractography maps to visualize the corpus callosum, fornix/fimbria, anterior commissure, cerebral peduncle, cerebellar peduncle, fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal), and optic tracts. We found that white matter connecting cortical hemispheres—the corpus callosum, ventral hippocampal commissure, and anterior commissure—showed a dramatic loss of tracts in Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− double mutant mice compared with the same structure in brains of WT or Itsn2−/− animals (Figs. 4B, 5A). In Itsn1Gt/Gt mice, tractography revealed that the midline crossing anterior portion of the anterior commissure (ACa) was not detectable (Fig. 4B). The posterior portion (ACp), which does not cross the midline, was present but greatly reduced. For the fornix/fimbria, interhemispheric crossing of the ventral hippocampal commissure was absent at the medial longitudinal fissure (Fig. 4B).

Figure 5.

A, Overlay of the white matter tracts from Figure 4B summarizes the loss of midline structure as viewed from below in WT vs Itsn1Gt/Gt brains. B, Representative white matter tracts, from each genotype, of cerebellar peduncle, fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal), and optic tracts were found to be similar between all genotypes suggesting normal development and guidance of these axonal tracts.

In contrast to the striking loss of interhemispheric connectivity along the medial longitudinal fissure, the cerebral peduncle, a cortical-originating tract that crosses the midline within the brainstem, was unaffected (Fig. 5B). Likewise, Itsn1 mutants did not differ from WT or Itsn2−/− animals in any of the noncortical tracts examined: cerebellar peduncle, trigeminal cranial nerve, and optic tract (Fig. 5B). Thus, Itsn1 is required for formation of cortically originating tracts along the medial longitudinal fissure, but dispensable for tracts crossing outside the cortex, regardless of whether fibers originate from noncortical or cortical regions.

Mutation of Itsn1 results in impaired learning and memory

A lack of midline corpus callosum could well affect neuronal function. To begin to analyze CNS function, we tested for bimanual motor coordination using the grid test—a task requiring a high degree of left-right proficiency (Tillerson and Miller, 2003; Mueller et al., 2009). Homozygous Itsn1 mutant mice (Itsn1Gt/Gt or Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− genotypes) displayed a significantly higher number of paw slips compared with WT mice in the grid test, indicating impaired bimanual motor coordination (Fig. 6A). Although Itsn2−/− performed no differently from WT, Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− mice performed significantly worse than Itsn1Gt/Gt animals (Fig. 6A). Thus, Itsn1 is required for formation of the midline corpus callosum. Although Itsn2 is not required for proper development of the corpus callosum, absence of Itsn2 does lead to decreased bimanual coordination, when combined with lack of Itsn1.

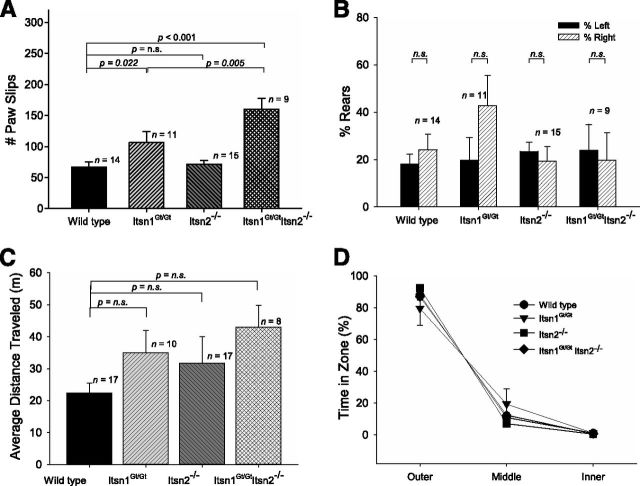

Figure 6.

Comparisons of motor, exploratory, and open field behaviors. A, Motor coordination task was measured by assessing the number of paw slips on a grid test. Itsn1 mutants (Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− mice) showed impaired motor coordination (F(3,45), = 11.91, p < 0.05). One-way ANOVA statistical tests were used to calculate individual p values. B, Exploratory coordination behavior was measured as forearm usage when standing on rear feet inside a vertical tube. There was no difference in the total number of rears in this cylinder test (F(3,45) = 1.94, p > 0.05). C, Average distance traveled during open field task. No statistical differences were observed. D, Anxiety test was measured as time spent in open field zones. The results of an ANOVA with between-group factor Genotype and within-group factor Zone (outer, middle, and inner) revealed no significant interaction between Genotype and Zone (F(6,96) = 1.40, p > 0.05). One-way ANOVA statistical tests were used to calculate individual p values.

Since incomplete callosal agenesis is strongly associated with cognitive impairment in humans (Raybaud and Girard, 2005), we tested whether the same was true for Itsn mutant mice. First, we observed general behavioral characteristics of the mice. While not quantified, home cage behaviors including feeding, grooming, breeding, and nursing, of mice from each genotype, appeared indistinguishable. Exploratory behavior was similar among Itsn1Gt/Gt, Itsn2−/−, Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/−, and WT mice (as assessed by quantifying right vs left rearing behavior in the cylinder test; Fig. 6B), as was average distance traveled over time in an open field (Fig. 6C). No preference for outer, middle, or inner zones of an open field was observed for any of the genotypes, indicating a lack of anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 6D). Thus, loss of Itsn1, Itsn2, or both genes did not affect gross behavioral traits.

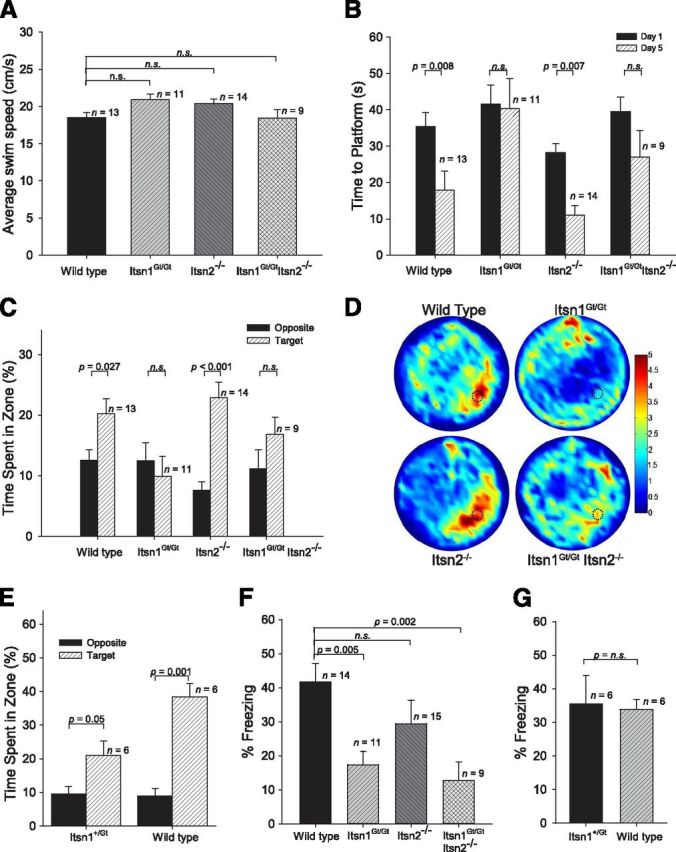

To specifically test for cognition, we analyzed Itsn mutants using hippocampal-dependent tests for spatial learning and memory: the hidden platform version of the Morris water maze and contextual fear conditioning (Fanselow, 1980; Morris et al., 1982). In water-maze testing, all genotypes had similar swimming speeds indicating that swimming motor control was not affected by loss of either gene (Fig. 7A). Over the five day period, WT and Itsn2−/− mice required progressively shorter times to find the platform (Fig. 7B), indicating that mice of these genotypes had learned the platform location. In contrast, the time spent finding the platform by Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− mice remained unchanged after five days of training, and thus, mice lacking Itsn1 failed to learn its location. Moreover, in probe tests with the escape platform removed, Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− mice spent an equal amount of time in all zones, whereas WT and Itsn2−/− mice showed a strong spatial bias for the zone where the platform was located during training (Fig. 7C,D). Heterozygous Itsn1+/Gt mice also showed a strong bias for this zone indicating that one copy of Itsn1 was sufficient for the test (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

Spatial memory deficits in Itsn mutants. A, Morris water maze. Average swimming speeds of all genotypes were indistinguishable (F(3,43) = 2.79, p > 0.05). B, Summary of training days in the water maze revealed Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− mice did not learn the platform location after 5 d. The results of a Genotype (Itsn1Gt/Gt, Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/−, Itsn2−/−, WT) × Day (1–5) ANOVA shows a significant effect of Genotype (F(3,43) = 6.21, p < 0.05) and Day (F(4,172) = 15.25, p < 0.001). C, During probe tests, Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− mutants were unable to find the target platform. An ANOVA with the between-subjects variable Genotype and within-subjects variable Zone (Target, Others) revealed a significant interaction (F(3,43) = 2.77, p = 0.05) as well as significant main effects of Genotype (F(3,43) = 4.94, p < 0.05) and Zone (F(1,43) = 15.49, p < 0.001). D, Heat map summary of Morris water maze where target zone is indicated by dotted circle. Increasing color intensity (arbitrary scale) represents increased time spent. E, During Morris water-maze probe tests, Itsn1+/Gt were able to find the target platform as well as WT. F, Performance in contextual fear conditioning task. Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− mice froze significantly less than Itsn2−/− and WT mice, which did not differ. Mice with a mutation in Itsn1 showed impaired contextual fear memory (F(3,44) = 6.04, p < 0.05). G, Itsn1+/Gt mice froze to the same degree as WT mice in the contextual fear conditioning task. One-way ANOVA statistical tests were used to calculate all individual p values.

In the contextual fear memory test, mice were placed in a conditioning chamber and given a footshock. When they were returned to the same conditioning chamber one day later, Itsn1Gt/Gt and Itsn1Gt/Gt Itsn2−/− mice froze much less frequently than did Itsn2−/− and WT mice, which did not differ from each other (Fig. 7F). Moreover, Itsn1+/Gt mice froze to a similar degree as WT mice in the contextual fear task (Fig. 7G). Thus, Itsn1 disruption results in major deficits in spatial learning and memory, while Itsn2 mutation had no observable effect. Double mutants were indistinguishable from Itsn1 mutants in this regard.

Discussion

Studies in invertebrate models revealed a conserved role for Itsn in synaptic transmission (Koh et al., 2004; Marie et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008). In Drosophila, mutation of Itsn results in lethality, whereas C. elegans lacking Itsn are viable (Koh et al., 2004; Marie et al., 2004; Rose et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Examination of fly larvae revealed abnormal neuromuscular junction synaptic bouton morphology and reduced synaptic vesicle number. Drosophila Itsn mutants also showed smaller EPSP amplitudes over time upon repeated strong stimulation compared with wild-type flies (Koh et al., 2004). This effect on amplitude was reversed by subsequent repeated stimulation at large intervals suggesting that decreased EPSP amplitude could be the result of membrane recycling deficits (Koh et al., 2004). Indeed, in D-Itsn mutants, several proteins that regulate endocytosis show reduced accumulation (Koh et al., 2004; Marie et al., 2004; O'Connor-Giles et al., 2008; Rodal et al., 2008). Loss of Itsn in C. elegans also resulted in decreased frequency of miniature postsynaptic current and a reduction of the number of active zone vesicles (Wang et al., 2008). We therefore examined synaptic physiology at Schaffer collateral–CA1 synapses from Itsn mutant brain slices. Surprisingly, synaptic deficits were not observed. Basal synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation of Itsn mutants were indistinguishable from WT littermates. Given the abnormalities in flies and worms, we expected that severe impairment of spatial learning in mice lacking Itsn1 would be associated with alteration in synaptic transmission or plasticity in the CA1 hippocampus. However, no such physiological abnormality was observed suggesting that Itsn function in vertebrates could be different from what is seen in invertebrates. Alternatively, underlying synaptic deficits are not sufficient to affect synaptic transmission under the conditions tested. Even Itsn double mutants showed no sign of abnormalities like those seen in the fly or worm. Another potential explanation for this difference might be that we measured synaptic activity at central synapses in contrast to the neuromuscular junctions, a peripheral synapse, which was studied in Drosophila and C. elegans. However, gross motor function appeared unaffected in Itsn mutant mice. Indeed, Itsn1 functions primarily to control axonal patterning in the rostral CNS.

After finding that callosal fibers failed to cross the midline in sections from Itsn1Gt/Gt mutant brains, we used MRI and DTI to characterize brain matter at high resolution. Our results revealed a novel and essential role for Itsn1 in formation of midline crossing tracts of the cortex. While Itsn1 mutants show some tract volume and integrity loss in other regions of the brain, impaired development of the corpus callosum, ventral hippocampal, and anterior commissures are the most striking white matter abnormalities. These deficits involved tracts along the medial longitudinal fissure, greatly reducing or eliminating intercortical connectivity between hemispheres. In contrast, white matter tracts not derived from the cortical plate are unaffected by loss of Itsn1. Given the learning and memory deficits in Itsn1Gt/Gt mice, it is noteworthy that cortical gray matter regions were not significantly different from WT mice. While each hemisphere can independently control simple tasks, information sharing via commissures permits more complex processing (Richards et al., 2004; Schmidt, 2008; O'Donnell et al., 2009; Evans and Bashaw, 2010). Indeed, in Itsn1 mutant mice, simple motor behaviors are intact while complex learning and bimanual functions are impaired. Interestingly, following surgical transection of hippocampal commissures, WT rats fail to navigate a radial arm maze (Olton et al., 1982). Also, animals with a unilateral lesion in the fornix and contralateral lesion in the entorhinal cortex performed as well as surgically manipulated control rats, highlighting an essential requirement for interhemispheric communication in spatial memory formation (Olton et al., 1982).

Itsn1 expression is turned on in the cortical plate at mouse embryonic stage E15.5. This is coincident with the time at which callosal axons cross the midline (Ozaki and Wahlsten, 1992), and axons originating from the cortical plate cannot form midline structures without Itsn1. As the corpus callosum is required for spatial memory formation, including fear conditioning (MacPherson et al., 2008), defective midline connectivity is the most parsimonious explanation for why Itsn1 mutants show learning impairment. Loss of Itsn1 can affect vesicular trafficking (Yu et al., 2008), therefore, Itsn1 may regulate trafficking of and/or signaling from guidance cues at the cortical midline. Indeed, many cell surface proteins, including Eph/Ephrin, Robo/Slit, DCC/Netrin, and FGFR-1 are known to regulate callosal midline crossing (Quinn et al., 2003; Lindwall et al., 2007; O'Donnell et al., 2009; Bashaw and Klein, 2010). And, Itsn proteins have already been implicated in EphB and ephrin-B1 pathways (Irie and Yamaguchi, 2002; Nishimura et al., 2006; Jørgensen et al., 2009). However, detailed genetic and physiological analysis of Itsn1 function at the cortical midline will be necessary to firmly delineate the molecular pathways affected in Itsn1 mutant mice.

In this study, we also found very little evidence for Itsn1/2 redundancy. Based on their shared sequence homology and overlapping tissue expression, this result was unexpected. It is possible, however, that Itsn2 does play a role related to Itsn1, which is not easily detected using the experimental approaches described herein. Indeed, while not statistically significant, Itsn2−/− mice did trend toward reduced freezing in the contextual fear task. And while Itsn1Gt/GtItsn2−/− double mutants are no worse than Itsn1 single mutants, this could simply reflect complete or near complete learning impairment in Itsn1 mutants already. As well, it is important to note that Itsn2 on its own does not appear to contribute meaningfully to CNS patterning; however, as the Itsn1 single mutants have a profound effect on white matter connectivity, it may not be possible for double mutant effects to be any worse.

Itsn1 function in commissural development has implications for human health. Ninety percent of humans born with complete callosal agenesis also lack hippocampal commissural midline crossing and half of these have anterior commissural malformation (Raybaud and Girard, 2005). Malformation of commissural midline trajectory is associated with behavioral problems in humans, such as communication disorders as well as learning and memory deficits (Richards et al., 2004; Paul et al., 2007). Thus, reduced expression or function of Itsn1 could have clinical implications. Indeed, humans with chromosomal deletions that include the ITSN1 locus exhibit severe cognitive impairment (Lindstrand et al., 2010).

Itsn1 disruption causes gross deficiency of learning and memory, indicative of its role in facilitating integration of higher order cognition in mammals. In Itsn1 mutants, axons that form the corpus callosum, ventral hippocampal, and anterior commissures do not link cortical hemispheres. Itsn1, therefore, is essential for cortical midline connectivity, a phenomenon involved in higher learning and cognitive processing. A recent comparison of conserved genes in two strains of yeast has shown that functional repurposing is often associated with acquisition of novel domains (Frost et al., 2012). Indeed, this appears to be the case with Itsn1, which has acquired novel biological role(s) in axonal guidance at the midline coincident with inclusion of C-terminal DBL/PH and C2 domains in a vertebrate and neural-specific isoform, Itsn1L.

Footnotes

This work was supported by funds from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI) to S.E.E., the CIHR to M.W.S., Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the CIHR to R.M.H., and the CIHR to S.A.J. M.W.S. is an International Research Scholar at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier I) in Neuroplasticity and Pain. R.M.H. holds a Canada Research Chair in Imaging. J.P.L. is supported by the CIHR. A.S.S. acknowledges funding from CCSRI. The Mouse Imaging Centre (MICe) acknowledges funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the Ontario Innovation Trust for providing facilities along with The Hospital for Sick Children. We thank D. Bosch, S. Spring, and C. Laliberte for their technical assistance. We thank L.-Y. Wang for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Aboitiz F, Montiel J. One hundred million years of interhemispheric communication: the history of the corpus callosum. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:409–420. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashaw GJ, Klein R. Signaling from axon guidance receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001941. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66:259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock NA, Nieman BJ, Bishop JB, Mark Henkelman R. In vivo multiple-mouse MRI at 7tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1311–1316. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr AE, Lerch JP, Spring S, Kabani N, Henkelman RM. High resolution three-dimensional brain atlas using an average magnetic resonance image of 40 adult C57Bl/6J mice. Neuroimage. 2008;42:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans TA, Bashaw GJ. Axon guidance at the midline: of mice and flies. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS. Conditioned and unconditional components of post-shock freezing. Pavlov J Biol Sci. 1980;15:177–182. doi: 10.1007/BF03001163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost A, Elgort MG, Brandman O, Ives C, Collins SR, Miller-Vedam L, Weibezahn J, Hein MY, Poser I, Mann M, Hyman AA, Weissman JS. Functional repurposing revealed by comparing S. pombe and S. cerevisiae genetic interactions. Cell. 2012;149:1339–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glodowski DR, Chen CC, Schaefer H, Grant BD, Rongo C. RAB-10 regulates glutamate receptor recycling in a cholesterol-dependent endocytosis pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4387–4396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guipponi M, Scott HS, Chen H, Schebesta A, Rossier C, Antonarakis SE. Two isoforms of a human intersectin (ITSN) protein are produced by brain-specific alternative splicing in a stop codon. Genomics. 1998;53:369–376. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie F, Yamaguchi Y. EphB receptors regulate dendritic spine development via intersectin, Cdc42 and N-WASP. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1117–1118. doi: 10.1038/nn964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen C, Sherman A, Chen GI, Pasculescu A, Poliakov A, Hsiung M, Larsen B, Wilkinson DG, Linding R, Pawson T. Cell-specific information processing in segregating populations of Eph receptor ephrin-expressing cells. Science. 2009;326:1502–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.1176615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh TW, Verstreken P, Bellen HJ. Dap160/intersectin acts as a stabilizing scaffold required for synaptic development and vesicle endocytosis. Neuron. 2004;43:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch JP, Carroll JB, Spring S, Bertram LN, Schwab C, Hayden MR, Henkelman RM. Automated deformation analysis in the YAC128 Huntington disease mouse model. Neuroimage. 2008;39:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch JP, Sled JG, Henkelman RM. MRI phenotyping of genetically altered mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;711:349–361. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-992-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrand A, Malmgren H, Sahlén S, Schoumans J, Nordgren A, Ergander U, Holm E, Anderlid BM, Blennow E. Detailed molecular and clinical characterization of three patients with 21q deletions. Clin Genet. 2010;77:145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindwall C, Fothergill T, Richards LJ. Commissure formation in the mammalian forebrain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson P, McGaffigan R, Wahlsten D, Nguyen PV. Impaired fear memory, altered object memory and modified hippocampal synaptic plasticity in split-brain mice. Brain Res. 2008;1210:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie B, Sweeney ST, Poskanzer KE, Roos J, Kelly RB, Davis GW. Dap160/intersectin scaffolds the periactive zone to achieve high-fidelity endocytosis and normal synaptic growth. Neuron. 2004;43:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihrshahi R. The corpus callosum as an evolutionary innovation. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2006;306:8–17. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O'Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297:681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller KL, Marion SD, Paul LK, Brown WS. Bimanual motor coordination in agenesis of the corpus callosum. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:1000–1011. doi: 10.1037/a0016868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman BJ, Flenniken AM, Adamson SL, Henkelman RM, Sled JG. Anatomical phenotyping in the brain and skull of a mutant mouse by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography. Physiol Genomics. 2006;24:154–162. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00217.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Yamaguchi T, Tokunaga A, Hara A, Hamaguchi T, Kato K, Iwamatsu A, Okano H, Kaibuchi K. Role of numb in dendritic spine development with a Cdc42 GEF intersectin and EphB2. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1273–1285. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor-Giles KM, Ho LL, Ganetzky B. Nervous wreck interacts with thickveins and the endocytic machinery to attenuate retrograde BMP signaling during synaptic growth. Neuron. 2008;58:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell M, Chance RK, Bashaw GJ. Axon growth and guidance: receptor regulation and signal transduction. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:383–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton DS, Walker JA, Wolf WA. A disconnection analysis of hippocampal function. Brain Res. 1982;233:241–253. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki HS, Wahlsten D. Prenatal formation of the normal mouse corpus callosum: a quantitative study with carbocyanine dyes. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:81–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul LK, Brown WS, Adolphs R, Tyszka JM, Richards LJ, Mukherjee P, Sherr EH. Agenesis of the corpus callosum: genetic, developmental and functional aspects of connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrn2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechstein A, Shupliakov O, Haucke V. Intersectin 1: a versatile actor in the synaptic vesicle cycle. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:181–186. doi: 10.1042/BST0380181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucharcos C, Casas C, Nadal M, Estivill X, de la Luna S. The human intersectin genes and their spliced variants are differentially expressed. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1521:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn CC, Chen E, Kinjo TG, Kelly G, Bell AW, Elliott RC, McPherson PS, Hockfield S. TUC-4b, a novel TUC family variant, regulates neurite outgrowth and associates with vesicles in the growth cone. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2815–2823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02815.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybaud C, Girard N. Malformations of the telencephalic commissures. In: Tortori-Donati P, Rossi A, editors. Pediatric neuroradiology. Berlin: Springer; 2005. pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- Richards LJ, Plachez C, Ren T. Mechanisms regulating the development of the corpus callosum and its agenesis in mouse and human. Clin Genet. 2004;66:276–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodal AA, Motola-Barnes RN, Littleton JT. Nervous wreck and Cdc42 cooperate to regulate endocytic actin assembly during synaptic growth. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8316–8325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2304-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S, Malabarba MG, Krag C, Schultz A, Tsushima H, Di Fiore PP, Salcini AE. Caenorhabditis elegans Intersectin: a synaptic protein regulating neurotransmission. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:5091–5099. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Hicks JL. ATP-evoked increases in intracellular calcium in neurons and glia from the dorsal spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1563–1575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01563.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MF. Using both sides of your brain: the case for rapid interhemispheric switching. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengar AS, Wang W, Bishay J, Cohen S, Egan SE. The EH and SH3 domain Ese proteins regulate endocytosis by linking to dynamin and Eps15. EMBO J. 1999;18:1159–1171. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengar AS, Salter MW, Egan SE. ITSN. In: Choi S, editor. Encyclopedia of signaling molecules. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 990–997. [Google Scholar]

- Spring S, Lerch JP, Henkelman RM. Sexual dimorphism revealed in the structure of the mouse brain using three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2007;35:1424–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Miller GW. Grid performance test to measure behavioral impairment in the MPTP-treated-mouse model of parkinsonism. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;123:189–200. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Bouhours M, Gracheva EO, Liao EH, Xu K, Sengar AS, Xin X, Roder J, Boone C, Richmond JE, Zhen M, Egan SE. ITSN-1 controls vesicle recycling at the neuromuscular junction and functions in parallel with DAB-1. Traffic. 2008;9:742–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles MV, Vauti F, Otte J, Füchtbauer EM, Ruiz P, Füchtbauer A, Arnold HH, Lehrach H, Metz T, von Melchner H, Wurst W. Establishment of a gene-trap sequence tag library to generate mutant mice from embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:13–14. doi: 10.1038/71622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamabhai M, Hoffman NG, Hardison NL, McPherson PS, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G, Kay BK. Intersectin, a novel adaptor protein with two Eps15 homology and five Src homology 3 domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31401–31407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Chu PY, Bowser DN, Keating DJ, Dubach D, Harper I, Tkalcevic J, Finkelstein DI, Pritchard MA. Mice deficient for the chromosome 21 ortholog Itsn1 exhibit vesicle-trafficking abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3281–3290. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]