Abstract

Objective

Based on eastern philosophy, mindfulness is becoming popular for human being’s mental health and well-being in western countries. In this study, we proposed to explore the effectiveness and potential pathway of mindfulness-based training (MBT) on Chinese Non-clinical higher education students’ cognition and emotion.

Methods

A paired control design was used. 48 higher education students (24 in MBT group, 24 in control group) were recruited in the study. The MBT group engaged in a 12-week MBT. A package of measurements, including sustained attention tasks (The Continuous Performance Test, CPT), executive function task (Stroop) for cognitive functions, the self-reported mindfulness levels (The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, MAAS) and emotion (The Profile of Mood States, POMS), were apply for all participants at baseline and every 4 weeks during next 12 weeks.

Results

There were no differences in baseline demographic variables between two groups. Over the 12-week training, participants assigned to MBT group had a significantly greater reduction in CPT reaction time (Cohen’s d 0.72), significantly greater improvement in positive emotion (Vigor-Activity, VA) (Cohen’s d 1.08) and in MAAS (Cohen’s d 0.49) than those assigned to control group. And, MAAS at 4th week could significantly predict the CPT RT and VA at 8th week in the MBT group. VA at 4th week could significantly predict the CPT RT at 8th week (B = 4.88, t = 2.21, p = 0.034, R2= 0.35).

Conclusion

This study shows the efficiency of 12-week MBT on Chinese Non-clinical students’ cognition and emotion. Mindfulness training may impact cognition and emotion through the improvement in mindfulness level, and may impact cognition through the improvement in positive emotion.

Keywords: mindfulness-based training, higher education students, non-clinical population, emotion, sustained attention, paired controlled design

Introduction

Mindfulness practice, which initially arose 2,500 years ago in eastern countries within the spiritual context of Buddhism (Kabatzinn, 2003), was systematically and scientifically examined by western scholars. Over the past decades, mindfulness practice has become quite popular in various research areas, such as psychology (Chambers et al., 2009; Chiesa et al., 2011), psychiatry (Chiesa and Serretti, 2011; Am et al., 2015), immunology (Chambers and Schauenstein, 2000), and neuroscience (Tang and Posner, 2015; Wheeler et al., 2017). The benefits of mindfulness-based trainings (MBTs) on physical, psychological and social functions have been well documented in western nations (Chiesa et al., 2011; Hülsheger et al., 2013). Mindfulness is commonly defined as “paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and Non-judgmentally” (Kabatzinn, 2003). To some extent, “paying attention on purpose” coincides with sustained attention, “in the present moment” coincides with executive function, and “Non-judgmentally” coincides with emotion regulation. Thus, the definition’s keywords point to cognitive and emotional capacity training.

A growing body of robust evidence from researches has demonstrated that MBTs are effective in improving a range of cognitive outcomes in comparison to control conditions, including sustained attention (Jha et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2007; Lutz et al., 2009; Schmertz et al., 2009; Zeidan et al., 2010) and executive functions (Diamond and Lee, 2011; Tang et al., 2012; Moynihan, 2013; Lyvers et al., 2014). And a systematic review of neuropsychological findings demonstrated the effect of MBT on cognitive abilities (Chiesa et al., 2011). In Chambers’ study, the MBT group’s overall reaction times (RTs) of the internal switching task significantly improved from T1 to T2, whereas the controls’ did not (Chambers et al., 2008).

Mindfulness have been shown to be effective in improving emotional well-being. In China, rapid urbanization and economic growth continue to negatively impact public mental health (Gong et al., 2012; Zhong et al., 2017). Meanwhile, both subjective self-reports and objective measurements of physiological indicators have indicated that MBT can decrease the intensity of emotional responses’ negativity (Arch and Craske, 2006) and increase emotional regulation ability (Chambers et al., 2015; Wheeler et al., 2017). Mindfulness significantly mediated the effects of MBTs on mental health outcomes, including anxiety, mood states, negative affect and depressive symptoms (z = 4.99, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001) in previous studies (Gu et al., 2015). Those results were even observed in patients with conditions such as Generalized Anxiety Disorder or depression (Goldin and Gross, 2010; Chambers et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015).

Although MBT has shown consistent efficacy for many physical and mental disorders in western country, less attention has been given to the possible benefits and feasibility that it may have in Non-clinical population, especially in China (Tang et al., 2007, 2009), the most populous eastern country in the world. Application of MBT might take effect in Non-clinical population as a tool for the reduction of stress, the improvement of quality of life and prevention of mental disorders. Continuous stress may lead to unproductive rumination that consumes energy and strengthens the experience of stress itself (Trapnell and Campbell, 1999), and too much stress can adversely affect emotion (Allen et al., 2014) and cognition (Liston et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2014). However, several reviews were found about MBT in Non-clinical population. In the review about Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for Non-clinical individuals in 2014 (Manoj and Rush, 2014), only 17 articles met the inclusion criteria and none of them focused on Chines. A meta-analysis in 2009 found only ten studies published before 2008 that focused on Non-clinical population (Chiesa and Serretti, 2009), and still none of these researches focused on Chinese volunteers.

Besides, mindfulness would be a more economical way to support young people’s health, while participation in higher education is growing among young people. 45.7% of young people now enter higher education in Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2018). Prevalence of mental illness in undergraduates becomes higher after first-year study (Macaskill, 2013). Thus, the higher education journey provides a golden opportunity for prevention of mental illness in young people.

In addition, although many research studies demonstrated in the west that mindfulness can reduce anxiety, depression (Hoge et al., 2013; Würtzen et al., 2013), insomnia (Ong et al., 2014), and relieve chronic diseases (Bohlmeijer et al., 2010), few studies have focused on the mechanisms of mindfulness and related studies only appeared in recent years (Bailey et al., 2016; Brake et al., 2016; Alsubaie et al., 2017; Lindsay and Creswell, 2017), and the underlying mechanism for mindfulness remains unclear.

Emotion and cognition improvements are commonly known as the outcomes of MBT; however, the roles they played during MBT were rarely explored. The relationship between emotion and cognition becomes a focus of research recently. In the spatial orienting tasks, where there is a faster response to targets appearing on the same side as an emotional cue (e.g., faces, spiders) and a slower response to those appearing on the opposite side (Mogg et al., 1997; Armony and Dolan, 2002). Anatomically, the amygdala (modulate the function of regions involved in early object perceptual processing) receives visual inputs from ventral visual pathways and sends feedback projections to all processing stages within this pathway (Eslinger, 1992). This finding may explain how pre-attentive processing of emotional events influences and enhances perception. Besides, Researches demonstrated that MBTs are effective in retrieval of specific autobiographical memories (Williams et al., 2000), a reliable cognitive marker of depression (Brittlebank et al., 1993). All these findings have shown that there might be a potential pathway of influencing cognition through emotion (Dolan, 2002).

In light of existing research literatures and current research needs, the present study attempted to: (a) determine the effectiveness of a 12-week MBT in Chinese Non-clinical population; (b) explore the potential pathway of mindfulness training through the relationship between the mindfulness level and cognition/emotion; (c) explore the potential pathway of mindfulness training through the relationship between the emotion and cognition.

We hypothesized that: (a) the 12-week MBT would affect Chinese Non-clinical higher education students’ cognition and emotion, resulting in a significant increase in sustained attention, executive function and positive emotion, as well as decrease in negative emotion; (b) mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition and emotion through the improvement in mindfulness level; (c) mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition through the improvement in emotion.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

A paired control trial was used in this study. The study was conducted aiming to investigate the effect of a MBT program compared with a control group. Participants were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) have no practice of any form of MBT; (2) over 18 years of age; (3) higher education student in Zhejiang university; (4) ability to communicate independently and understand tasks; (5) willing to participate in the research and give informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (1) severe neuropsychological impairment; (2) psychosis or dissociative disorders.

A total of 54 participants were recruited through a voluntary research participation of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China. All the 54 participants responded to the study announcement and all the participants interested by the study were included. Participants were matched by sex and age, after which the paired two participants were randomly assigned to mindfulness training group or control group. Randomization function in Excel 2016 was used and performed by the principal investigator prior to any contact with participants. Participants in MBT group were asked to complete 12-week MBT, and the participants in control group got brief poster about MBT. Follow-up assessments were scheduled with the participants and they were provided a reminder 1 week before. All participants completed the first assessment, and 48 of them completed the entire study (6 dropouts/11.1%). Six participants refused to participate in the follow-up study.

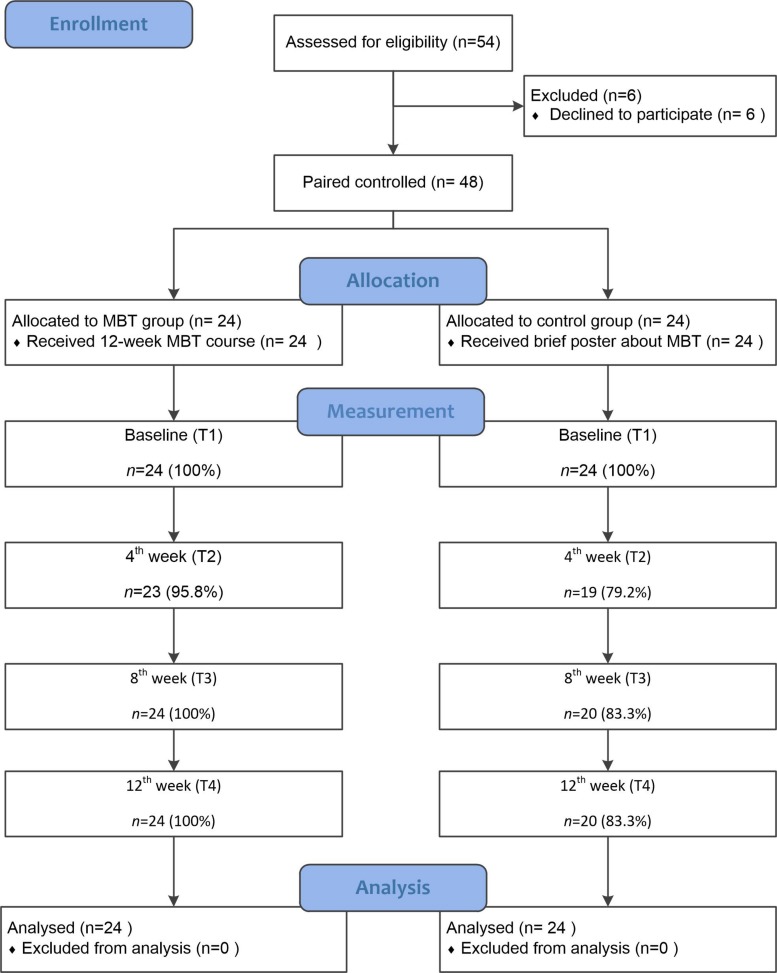

The training lasted 12 weeks. The MBT course followed the original MBSR structure. Demographic data, together with information about mindfulness, emotion, sustained attention and executive function were collected. Participants were assessed at the recruitment baseline (T1), after 4-week training (T2), after 8-week training (T3) and after 12-week training (T4) (see Figure 1). The attendances of MBTs and measurements were recorded, indicating that all the absences were due to unavailable of schedule. Recruitment and assessment procedures were conducted in the Zhejiang university. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang University. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

FIGURE 1.

Research procedures.

TZ enrolled participants and assigned participants to intervention, JX generated the allocation sequence.

Mindfulness Training

The MBT delivered to the training group was modeled on Jon Kabat-Zinn’s MBSR Curriculum, as described on the Palouse Mindfulness website of Dr. Dave Potter, Certified MBSR Teacher. The training’s content was rooted in an academic 12-week mindfulness course’s curriculum designed by a University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness-certified teacher. All mindfulness lessons were conducted by the third author (AM), who had 2 years of personal mindfulness practice and 6 months of experience in leading a mindfulness continuing practice group. The facilitator did not have a certification in mindfulness teaching, but this situation is similar to the one of many teachers delivering mindfulness training in schools or online (Napoli et al., 2005; Mendelson et al., 2010; Cavanagh et al., 2013).

Table A1 outlines the content of the training. Exercises included mindfulness meditation practice (body scan, breath meditation, emotion and thought meditation…) as well as mindfulness skills (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Non-identify (RAIN) technique…). Participants were encouraged to meditate at least 5 times a week between 10 and 20 min. The training group received MBT once a week and each session lasted about 1.5–2 h. Participation in sessions and out-of-class meditation was voluntary.

Measures

Mindfulness

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) was used as a dispositional measure of mindfulness. The MAAS is a 15-item scale assessing the frequency of mindful states in day-to-day life through the rating of both general and situation-specific statements. Higher scores indicated higher individual mindfulness level. The MAAS was shown to successfully report changes in mindfulness levels after MBT in several studies (Carlson and Brown, 2005; Shapiro et al., 2007). One previous study measured the MAAS’s Cronbach’s alpha level at 0.87 (Morone et al., 2016). The Chinese version revised by Chen also displays a high degree of validity with a Cronbach’s alpha level of 0.89 among Chinese participants (Chen et al., 2012). Cronbach’s alpha for MAAS in this study was 0.88.

Sustained Attention

The Continuous Performance Test (CPT) was used to assess sustained attention. CPT is a classical experimental paradigm for measuring sustained attention. The CPT has shown validity in different studies (Cornblatt et al., 1988; Berger and Cassuto, 2014; Junwon et al., 2015). In this task, participants were required to monitor a single letter of visual and to respond when a target stimulus occurred. The CPT was programmed in MATLAB utilizing a Lenovo LXM-L17AB computer. The task consisted of 11 letters (40 pt) flashing on the center of a video monitor (a 25.8 × 34.4 cm screen) for 130 ms at the rate of 600 ms between letters. The target was the letter X followed by the letter A. The task involved pressing the space key when the target appeared and avoiding responding to the other letter combinations (Klee and Garfinkel, 1983). CPT-AX task was chosen and included the capital letters A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, L, X as stimulus. The participant is asked to respond as quickly as possible when the letter ‘X’ is followed by the letter ‘A’. True positives, false alarms and reaction time are recorded as dependent measures. There is a total of 20 target sequences out of a total of 960 trials. Each block contained 240 stimuli, and there were 4 blocks in total. In addition, participants followed a practice program before entering the formal experiment. Omission errors were scored for each target missed, while commission errors were scored for a response made to a Non-target stimulus (Klee and Garfinkel, 1983). Each experiment lasted for about 30 min.

Executive Functions

The Stroop is a classical experimental paradigm for measuring executive function, which was programmed in E-prime utilizing a Lenovo LXM-L17AB e computer with 17-inch color display and resolution of 1024 × 768. The refresh rate was 75 Hz. The stimulus were Chinese characters “ ”, “

”, “ ”, “

”, “ ”, “

”, “ ” (meaning “red”, “yellow”, “blue”, “green,” respectively). The stimuli were written in red, yellow, blue, green, respectively in congruent situation, and they were written randomly in red, yellow, blue, green in incongruent situation. The experiment consists of 4 blocks. Each block had 16 trials. The task involved judging the color of the stimulus and press the corresponding key: F for “red,” G for “yellow,” H for “blue” and J for “green.” Participants were asked to respond accurately and quickly. Participants first gazed to a cross ‘+’ for 800 ms, then the stimulus appeared for 150 ms, and 1750 ms were left for the participant to respond. A two-block practice program was available before the participant entered the formal experiment. An accuracy rate above 90% only allowed participants to enter the formal experiment. The experimental design balances variables such as consistency, color, prospective memory stimuli, and so on. The distance between the subjects and the monitor was about 60 cm, and all stimuli were presented in the center of the display screen, on a black background. The experiment was carried out in a soundproofed room and lasted for about 5 min.

” (meaning “red”, “yellow”, “blue”, “green,” respectively). The stimuli were written in red, yellow, blue, green, respectively in congruent situation, and they were written randomly in red, yellow, blue, green in incongruent situation. The experiment consists of 4 blocks. Each block had 16 trials. The task involved judging the color of the stimulus and press the corresponding key: F for “red,” G for “yellow,” H for “blue” and J for “green.” Participants were asked to respond accurately and quickly. Participants first gazed to a cross ‘+’ for 800 ms, then the stimulus appeared for 150 ms, and 1750 ms were left for the participant to respond. A two-block practice program was available before the participant entered the formal experiment. An accuracy rate above 90% only allowed participants to enter the formal experiment. The experimental design balances variables such as consistency, color, prospective memory stimuli, and so on. The distance between the subjects and the monitor was about 60 cm, and all stimuli were presented in the center of the display screen, on a black background. The experiment was carried out in a soundproofed room and lasted for about 5 min.

Emotion

The Profile of Mood States -Short Form (POMS-SF) was used to measure emotion. The POMS-SF is a 30-item inventory measuring current mood state through statement ratings (e.g., I feel calm) on a Likert scale (0–4). The questionnaire consists of six subscales: “Tension-Anxiety (TA)”, “Depression-Dejection (DD)”, “Confusion-Bewilderment (CB)”, “Fatigue-Inertia (FI)”, “Anger-Hostility (AH)” and “Vigor-Activity (VA).” A total negative mood score was calculated by subtracting the vigor scale from the sum of the remaining subscales. The scale showed good validity in related studies (Tang et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2015). The Chinese version revised by Wang also displays a high degree of validity with a Cronbach’s alpha level of 0.7∼0.9 in subscales among Chinese participants (Wang and Lin, 2000). Cronbach’s alpha for POMS-SF in this study was 0.90.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses, t-test and Chi-square test were used to examine the group difference of basic characteristics. Linear mixed models were performed to account for the training effects. We fitted mixed-effects regression models for continuous variables (CPT RT, Stroop RT, VA, and so on; effect size reported in Cohen’s d) using baseline and 4th, 8th, and 12th week data. We tested the training effect between the two groups, controlling for sex, age and the baseline value of the outcome of interest. The mixed-effects models contain both fixed and random effects, with the fixed effects modeling treatment differences and random effects accounting for intra-subject variability. The regression models were conducted to explore the relationship between the outcome of mindfulness on emotion/cognition and between the outcome of emotion on cognition. Sex and baseline measure of each outcome measure were used as covariates in regression analyses. All analyses were implemented in SPSS.20.

Missing data were determined to be missing completely at random (MCAR) and suitable for using mixed-effects models analysis. We decided not to impute missing data to avoid introduction of extra bias to the model.

Results

Demographic and Functional Characteristics Between Two Groups

The MBT group (n = 24, age = 24.13 ± 5.11) consisted of 18 females (75%) and 6 males. The control group (n = 24, age = 24.25 ± 5.17) consisted of 16 females (66.7%) and 8 males. Demographic or baseline characteristics did not differ between the two groups [age (t = 0.08, p = 0.933), sex (χ2 = 0.40, p = 0.525), CPT hit rate baseline (t = 0.78, p = 0.970), CPT RT baseline (t = 0.04, p = 0.441), Stroop RT baseline (t = 0.44, p = 0.659), Stroop accuracy baseline (t = 1.41, p = 0.166), VA baseline (t = 0.26, p = 0.800), Negative emotion baseline (t = 0.63, p = 0.532), MAAS baseline (t = 1.17, p = 0.250) (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and functional characteristics between two groups.

| Baseline demographic characteristics | MBT group (N = 24) M ± SD | Control group (N = 24) M ± SD | t /χ2 | p |

| Female | 18 (75%) | 16 (66.7%) | 0.40 | 0.525 |

| Age | 24.13±5.11 | 24.25±5.17 | 0.08 | 0.933 |

| CPT hit rate baseline | 0.96±0.06 | 0.97±0.03 | 0.78 | 0.970 |

| CPT RT baseline | 421.05±79.17 | 420.27±65.81 | 0.04 | 0.441 |

| Stroop RT baseline | 971.41±355.63 | 1015.81±337.17 | 0.44 | 0.659 |

| Stroop accuracy baseline | 0.93±0.07 | 0.95±0.06 | 1.41 | 0.166 |

| VA baseline | 14.25±3.89 | 14.50±2.83 | 0.26 | 0.800 |

| Negative emotion baseline | 59.08±14.23 | 56.29±16.43 | 0.63 | 0.532 |

| MAAS baseline | 56.67±14.49 | 60.96±10.76 | 1.17 | 0.250 |

MBT, mindfulness-based training; CPT, the continuous performance test; VA, vigor-activity; MAAS, mindful attention awareness scale.

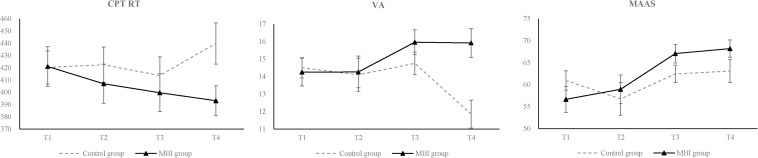

MBTs’ Effect on Cognition and Emotion

Table 2 presents results from the mixed models analyses. There were interactions between time and group in CPT RT [F(127.59) = 3.66, p = 0.014], VA [F(127.98) = 4.8, p = 0.003] and MAAS [F(127.68) = 3.08, p = 0.03], indicating that participants assigned to MBT group had a significantly greater reduction in CPT reaction time, significantly greater improvement in positive emotion and in MAAS than those assigned to control group (see Figure 2). Main effect of group for VA [F(43.54) = 5.3, p = 0.026] is significant, for CPT RT [F(44.24) = 3.86, p = 0.056] and MAAS [F(44.62) = 3.65, p = 0.063] were marginal significant (see Table 2). There were two main effects of time, for Stroop RT and MMAS.

TABLE 2.

Mixed model analyses with between-group effect sizes (N = 48).

| Outcome measures |

Treatment group |

Time |

Treatment group x time |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

|||||||||

| F | p | F | p | F | p | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | ES | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | ES | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | ES | ||||

| CPT_RT | F(44.24) = 3.86 | 0.056 | F(127.48) = 1.24 | 0.299 | F(127.59) = 3.66 | 0.014 | 9.42 | (−34.83, 53.68) | 0.22 | 10.88 | (−35.1, 56.85) | 0.2 | 46.78 | (5.45, 88.1) | 0.72 |

| CPT hit rate | F(40.27) = 0.5 | 0.484 | F(122.93) = 2.49 | 0.064 | F(123.03) = 0.41 | 0.745 | 0.02 | (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.42 | 0.01 | (−0.02, 0.04) | 0.2 | 0 | (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.09 |

| Stroop RT | F(43.2) = 0.38 | 0.541 | F(126.79) = 11.55 | <0.001 | F(126.89) = 0.25 | 0.86 | 39.44 | (−142.03, 220.91) | 0.14 | −21.7 | (−132.45, 89.05) | 0.12 | 83.93 | (−41.31, 209.17) | 0.42 |

| Stroop accuracy | F(44.26) = 0.79 | 0.38 | F(129.22) = 0.83 | 0.479 | F(129.38) = 1.89 | 0.134 | −0.03 | (−0.09, 0.03) | 0.31 | −0.02 | (−0.05, 0.01) | 0.36 | −0.03 | (−0.08, 0.01) | 0.48 |

| VA | F(43.54) = 5.3 | 0.026 | F(127.83) = 2.34 | 0.077 | F(127.98) = 4.8 | 0.003 | −0.16 | (−2.81, 2.49) | 0.04 | −1.21 | (−3.18, 0.77) | 0.38 | −4.07 | (−6.41, −1.72) | 1.08 |

| Negative emotion | F(43.86) = 0.56 | 0.458 | F(127.51) = 0.64 | 0.592 | F(127.7) = 0.78 | 0.506 | −1.65 | (−14.39, 11.1) | 0.08 | 2.05 | (−8.43, 12.53) | 0.12 | 4.23 | (−5.15, 13.6) | 0.28 |

| MAAS | F(44.62) = 3.65 | 0.063 | F(127.54) = 8.51 | <0.001 | F(127.68) = 3.08 | 0.03 | −2.21 | (−12.16, 7.75) | 0.14 | −4.63 | (−10.61, 1.34) | 0.48 | −5.11 | (−11.59, 1.37) | 0.49 |

ES, Between-group effect size (Cohen’s d); T2, 4th week; T3, 8th week; T4, 12th week; CPT RT, The continuous performance test reaction time; VA, vigor-activity.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of cognition, emotion and mindfulness level during 12 weeks for the MBT and control group. Significance was found in The Continuous Performance Test reaction time (CPT RT), Vigor-Activity (VA) and Mindful Attention Awareness Scale score (MAAS). Error bars indicate 1 SD.

The Effect of Mindfulness Level Predicted Change on Cognition and Emotion

Regression model 1 and 7 were conducted to explore the effect of group on cognition at T3 and T4. Regression model 2, 5, 8 11 were conducted to explore the effect of group on mindfulness level at T2 and T3. Regression model 3 and 9 were conducted to explore the effect of mindfulness level at Tn and Group in predicting cognition at Tn+1 (1 < n ≤ 3). Regression model 4 and 10 were conducted to explore the effect of group on positive emotion at T3 and T4. Regression model 6 and 12 were conducted to explore the effect of mindfulness level at Tn and Group in predicting positive emotion at Tn+1 (1 < n ≤ 3).

Regression model 1 was designed to estimate the effect of Group in predicting CPT RT T3. The regression coefficient of group in this model was −11.44, p = 0.541, F(3) = 7.60, R2= 0.33, p < 0.001 (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Regression analysis showing the extent to MAAS predicted change on the outcome measures.

| Model | Dependent variable | Independent variable | B | SE | t | p1 | F | df | R2 | p2 |

| Model 1 | CPT RT T3 | Group | –11.44 | 18.54 | –0.62 | 0.541 | 7.60 | 3 | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 165.73 | 53.63 | 3.09 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Model 2 | MAAS T2 | Group | 3.00 | 4.74 | 0.63 | 0.530 | 2.22 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.101 |

| Constant | 40.23 | 11.78 | 3.41 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Model 3 | CPT RT T3 | MAAS T2 | 1.33 | 0.57 | 2.31 | 0.027 | 6.99 | 4 | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| Group | –16.92 | 17.73 | –0.95 | 0.346 | ||||||

| Constant | 85.96 | 65.02 | 1.32 | 0.195 | ||||||

| Model 4 | VA T3 | Group | 1.23 | 0.97 | 1.27 | 0.210 | 1.63 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.198 |

| Constant | 11.20 | 2.14 | 5.24 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Model 5 | MAAS T2 | Group | 3.00 | 4.74 | 0.63 | 0.530 | 2.22 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.101 |

| Constant | 40.23 | 11.78 | 3.41 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Model 6 | VA T3 | MAAS T2 | –0.08 | 0.03 | –2.77 | 0.009 | 3.41 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.018 |

| Group | 1.54 | 0.90 | 1.71 | 0.095 | ||||||

| Constant | 16.80 | 2.80 | 6.01 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Model 7 | CPT RT T4 | Group | –46.87 | 17.17 | –2.73 | 0.009 | 9.08 | 3 | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 223.01 | 50.57 | 4.41 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Model 8 | MAAS T3 | Group | 5.66 | 2.71 | 2.09 | 0.043 | 4.64 | 3 | 0.20 | 0.007 |

| Constant | 41.48 | 6.75 | 6.15 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Model 9 | CPT RT T4 | MAAS T3 | –0.18 | 1.00 | –0.18 | 0.857 | 6.28 | 4 | 0.35 | <0.001 |

| Group | –44.14 | 18.76 | –2.35 | 0.024 | ||||||

| Constant | 228.54 | 67.29 | 3.40 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Model 10 | VA T4 | Group | 3.97 | 1.17 | 3.39 | 0.002 | 4.62 | 3 | 0.20 | 0.007 |

| Constant | 8.79 | 2.63 | 3.34 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Model 11 | MAAS T3 | Group | 5.66 | 2.71 | 2.09 | 0.043 | 4.64 | 3 | 0.20 | 0.007 |

| Constant | 41.48 | 6.75 | 6.15 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Model 12 | VA T4 | MAAS T3 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.60 | 0.118 | 4.27 | 4 | 0.24 | 0.006 |

| Group | 3.72 | 1.23 | 3.02 | 0.005 | ||||||

| Constant | 3.20 | 4.29 | 0.75 | 0.460 |

Model 1, using Group as a predictor for CPT RT T3; Model 2 and Model 5, using Group as a predictor for MAAS T2; Model 3, using MAAS T2 and Group as predictors for CPT RT T3; Model 4, using Group as a predictor for VA T3; Model 6, using MAAS T2 and Group as predictors for VA T3; Model 7, using Group as a predictor for CPT RT T4; Model 8 and Model 11, using Group as a predictor for MAAS T3; Model 9, using MAAS T3 and Group as predictors for CPT RT T4; Model 10, using Group as a predictor for VA T4; Model 12, using MAAS T3 and Group as predictors for VA T4; Sex and baseline measure of each outcome measure used as covariates in all analyses. p1, significance of the coefficient; p2, significance of the regression model. MAAS, mindful attention awareness scale; CPT RT, The continuous performance test reaction time; VA, vigor-activity; T2, 4th week; T3, 8th week; T4, 12th week.

Regression model 2 and 5 was designed to estimate the effect of Group in predicting MAAS T2. The regression coefficient of group in this model was 3.00, p = 0.53, F(3) = 2.22, R2 = 0.08, p = 0.101.

Regression model 3 was designed to estimate the effects of MAAS T2 and Group in predicting CPT RT T3. The regression coefficient of MAAS T2 in this model was 1.33, p = 0.027, of group in this model was −16.92, p = 0.346, F(4) = 6.99, R2= 0.37, p < 0.001, suggesting that the MAAS at T2 could significantly predict the CPT RT at T3.

Regression model 4 was designed to estimate the effect of Group in predicting VA T3. The regression coefficient of group in this model was 1.23, p = 0.210, F(3) = 1.63, R2 = 0.04, p = 0.198.

Regression model 6 was designed to estimate the effects of MAAS T2 and Group in predicting VA T3. The regression coefficient of MAAS T2 in this model was −0.08, p = 0.009, of group in this model was 1.54, p = 0.095, F(4) = 3.41, R2 = 0.19, p = 0.018, suggesting MAAS at T2 could significantly predict the VA at T3.

The Effect of Positive Emotion Predicted Change on Cognition

Regression model 13 and model 16 were conducted to explore the effect of mindfulness level at Tn and Group in predicting cognition at Tn+2 (1 < n ≤ 2). Regression model 14 and 17 were conducted to explore the effect of mindfulness level at Tn and Group in predicting positive emotion at Tn+1 (1 < n ≤ 2). Regression model 15 and 18 were conducted to explore the effect of mindfulness level at Tn and positive emotion at Tn+1 in predicting cognition at Tn+2 (1 < n ≤ 2).

Regression model 13 was designed to estimate the effect of MAAS T1 and group in predicting CPT RT T3. The regression coefficient of MAAS T1 in this model was 0.07, p = 0.93, F(4) = 5.55, R2= 0.31, p = 0.001 (see Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Regression analysis showing the extent to positive emotion predicted change on cognition.

| Model | Dependent variable | Independent variable | B | SE | t | p1 | F | df | R2 | p2 |

| Model 13 | CPT RT T3 | MAAS T1 | 0.07 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 5.55 | 4 | 0.31 | 0.001 |

| Group | –11.33 | 18.83 | –0.60 | 0.551 | ||||||

| Constant | 162.29 | 66.89 | 2.43 | 0.020 | ||||||

| Model 14 | VA T2 | MAAS T1 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.519 | 1.06 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.387 |

| Group | 0.18 | 1.31 | 0.14 | 0.889 | ||||||

| Constant | 13.81 | 3.75 | 3.68 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Model 15 | CPT RT T3 | VA T2 | 4.88 | 2.21 | 2.21 | 0.034 | 5.35 | 5 | 0.35 | <0.001 |

| MAAS T1 | –0.24 | 0.74 | –0.32 | 0.751 | ||||||

| Group | –14.72 | 18.07 | –0.81 | 0.421 | ||||||

| Constant | 114.30 | 71.90 | 1.59 | 0.121 | ||||||

| Model 16 | CPT RT T4 | MAAS T2 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 1.76 | 0.087 | 7.23 | 4 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

| Group | –47.41 | 17.81 | –2.66 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Constant | 155.28 | 66.40 | 2.34 | 0.025 | ||||||

| Model 17 | VA T3 | MAAS T2 | –0.08 | 0.03 | –2.77 | 0.009 | 3.41 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.018 |

| Group | 1.54 | 0.90 | 1.71 | 0.095 | ||||||

| Constant | 16.80 | 2.80 | 6.01 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Model 18 | CPT RT T4 | VA T3 | –0.62 | 3.08 | –0.20 | 0.841 | 5.63 | 5 | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| MAAS T2 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 1.50 | 0.143 | ||||||

| Group | –46.36 | 18.80 | –2.47 | 0.019 | ||||||

| Constant | 166.25 | 86.53 | 1.92 | 0.063 |

Model 13, using MAAS T1 as a predictor for CPT RT T3; Model 14, using MAAS T1 as a predictor for VA T2; Model 15, using MAAS T1 and VA T2 as predictors for CPT RT T3; Model 16, using MAAS T2 as a predictor for CPT RT T4; Model 17, using MAAS T2 as a predictor for VA T3; Model 18, using MAAS T2 and VA T3 as predictors for CPT RT T4; Sex and baseline measure of each outcome measure used as covariates in all analyses. p1, significance of the coefficient; p2, significance of the regression model. MAAS, mindful attention awareness scale; CPT RT, The continuous performance test reaction time; VA, vigor-activity; T2, 4th week; T3, 8th week; T4, 12th week.

Regression model 14 was designed to estimate the effect of MAAS T1 and group in predicting VA T2. The regression coefficient of MAAS T1 in this model was 0.03, p = 0.519, F(4) = 1.06, R2 = 0.01, p = 0.387.

Regression model 15 was designed to estimate the effects of MAAS T1, VA T2 and Group in predicting CPT RT T3. The regression coefficient of VA T2 in this model was 4.88, p = 0.034, of MAAS T1 in this model was −0.24, p = 0.751, F(5) = 5.35, R2= 0.35, p = 0.001, suggesting that the VA at T2 could significantly predict the CPT RT at T3.

Discussion

Based on eastern philosophy, mindfulness is becoming very popular for individuals seeking mental health and well-being in western countries. Although MBT has shown consistent efficacy for many disorders in western population, less attention has been given to the possible benefits that mindfulness may have in Non-clinical population, especially in China, one of the biggest countries in the eastern world.

This research mainly demonstrates that (a) a 12-week MBT can effectively improve sustained attention and positive emotion in Chinese Non-clinical population, (b) mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition and emotion through the improvement in mindfulness level; (c) mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition through the improvement in emotion.

The effect of MBT on cognition improvement is consistent with previous studies (Davidson et al., 1976; Jha et al., 2007; Schmertz et al., 2009; Zeidan et al., 2010; Lee and Orsillo, 2014; Morone et al., 2016). Meditation training might explain participants’ improved ability to focus, since meditation instructs to focus attention on breath, body parts, sounds, and Non-judgmentally come back to the object of focus when noticing mind-wandering.

In this study, the MBT was able to significantly improve participant’s positive emotion. This was consistent with previous research showing that control groups experienced significant drops in vigor and elevated levels of negative emotions compared to MBSR participants (Rosenzweig et al., 2003). Mindfulness practice may act as protective factor against the increased fatigue associated with repeated measures, helping participants to cultivate decreased emotional resistance and reactivity to present feelings, open and curious attitudes toward present-moment experience, and disengagement from rumination, a cognitive process shown to increase work-related fatigue (Deyo et al., 2009; Campbell et al., 2012).

The present findings of significant improvement in positive emotions and sustained attention in Non-clinical population offers new avenues for the application of mindfulness. The effects of MBT on individuals suffering from a variety of illnesses, like anxiety (Goldin and Gross, 2010; Mankus et al., 2013; Würtzen et al., 2013), depression (Deyo et al., 2009; Würtzen et al., 2013), chronic diseases (Bohlmeijer et al., 2010) and even cancer (Würtzen et al., 2013) have been demonstrated. In regard to Non-clinical individuals without obvious illnesses, however, this study’s findings bring two contributions. Firstly, mental health well-being rates may benefit from bringing clinical and Non-clinical population together in MBT, while both of them would benefit from MBT. In China, psychotherapy is underutilized because of stigma (Brown et al., 2010; Yap and Jorm, 2011), and treatment-seeking rates are less than 6% for common mental disorders (i.e., mood and anxiety disorders) (Charlson et al., 2016). Thus, mixing Non-clinical and clinical population in MBT could increase mental health seeking behaviors by reducing stigma. Secondly, stress is a pervasive issue in modern society and has become a global public health problem (Romas, 2009). Application of MBT might take effect in Non-clinical population as a tool for stress reduction, improvement of psychotherapy quality and prevention of mental disorders. Thus, MBT could serve as a preventative therapy and reduce stress that leads to unproductive rumination that consumes energy (Trapnell and Campbell, 1999), and can adversely affect emotion (Allen et al., 2014) and cognition (Liston et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2014).

Besides, we explored the potential pathway of mindfulness and found that mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition and emotion through the improvement in mindfulness level. It was in accordance with the previous studies (Gu et al., 2015). This finding provides evidence for exploring the mechanism of mindfulness training, which stressing the importance of mindfulness level measurement. Further research could be refined to determine which component of mindfulness work on these outcomes. It might be the mindfulness attitude (such as acceptance) or mindfulness related practice (such as body scanning). And, at what point the component begins to take effect could also be studied to further explore the mechanisms of mindfulness.

The results indicated that mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition through the improvement in emotion, which was a complement to the knowledge that rare studies have provided evidence for the assumption that mindfulness may impact cognition through emotion. Positive emotion at T2 could significantly predict sustained attention at T3, but this relationship did not exist in positive emotion at T3 and sustained attention at T4. There are three possible reasons. Firstly, the reduced size of the sample is one limitation. Secondly, the lack of follow-up measurement making it difficult to assess if anything is happened and maintained after the intervention. Thirdly, experimental paradigms and cognitive indicators used in this study may not be sensitive enough to indicated a stabilization trend, and the experimental paradigms and cognitive indicators need to be improved in the future. Nonetheless, the results of this research partially support our hypothesis that mindfulness training may take effect through the potential pathway of influencing cognition through the improvement in emotion. Recent studies begin to focus on the relationship between outcomes of mindfulness training, but there is no direct evidence to support. Now we could see the light of dawn on the horizon. Based on these results of the pilot study, we could improve the study design and measurements in the following research, and further verify our experimental hypothesis in larger sample. The potential pathway of mindfulness through the relationship between cognition and emotion establishes a base from which further studies could continue investigating the mechanisms for mindfulness. Future research should extend this small body of evidence for emotion as mechanisms.

The evidence of effectiveness of MBT was supported in Chinese Non-clinical populations. Mindfulness originated from eastern philosophy, but less attention has been given to Chinese populations while China is the most populous eastern country. The effectiveness of MBT in Chinese populations can further extend the application of mindfulness. Besides, there are many similarities between Chinese culture and the concept of mindfulness. Further studies are necessary to explore the difference of MBT effect between eastern and western populations.

While the results of the study are promising, a couple limitations should nonetheless be kept in mind. Firstly, a wait-list condition would might be more effective to future studies. Because the control group was not active, these results could be partly explained by an effect related to the group intervention setting (i.e., social support, shared positive emotions) and not the mindfulness training itself. Secondly, there was no follow-up measurement after the intervention program, making it difficult to assess if anything is maintained after the intervention and therefore, making it difficult to make interpretative hypothesis related to a potential prevention effect of the program on medium or long term. Thirdly, regarding validity, the size of the participants’ sample was small and the ratio male/female, reduced. Thus, further research should explore the significance of a larger sample size. Fourthly, trainees’ mental health was assessed as “Non-clinical” without use of formal scales for mental health disorders before the study. Future studies could use scales to ensure participants’ condition. Finally, no formal tracking of trainee’s personal practice occurred. Yet, participants reported in sessions practicing every week. Thus, this study’s results open avenues of research regarding the feasibility and effectiveness of mindfulness-based trainings adopting voluntary participation. Besides, mindfulness serving as an effective self-help method (Lever et al., 2014), more researchers are turning their attention to web-based mindfulness trainings (Cavanagh et al., 2013; Dimidjian et al., 2014), which involve reduced monitoring of personal practice. Further research exploring the effectiveness of MBT in China could have beneficial implications for the spread of MBT among Chinese populations.

Data Availability

The data sets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang University. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

TZ and SC contributed to the conception and design of the study. TZ organized the database. TZ and JX performed the statistical analysis. TZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JX, AM, and SC wrote sections of the manuscript. WW designed the program. YJ assisted with the data collection. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

AM was involved in the creation and/or facilitation of the MBT evaluated in this study. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in this study.

Appendix

TABLE .

Description of 12-Week Mindfulness Training.

| Week | Topic | Content |

| 1 | Mindfulness Introduction | Introductions, training schedule; Exercise on recognizing auto-pilot and automatic thinking with introduction to awareness of breath, body, and surroundings; Mindfulness definition and usual misconceptions |

| 2 | Exploring Here and Now | Introduction to Mindful Logs and Gratitude Journal; Mindful Eating: Raisin meditation; Intro to Body Scan Meditation (BSM) |

| 3 | Mindful Yoga | Introduction to Mindful Yoga, 40’ Mindful Yoga Session; Sharing of experience with BSM |

| 4 | 9 Mindfulness attitudes | 15-min BSM; Introduction to mindfulness’s 9 attitudes; 7-min MM on Emotions |

| 5 | Managing Stress and Difficult Situations | 20 min MM on emotions; Introduction of RAIN Method; The Guest House Poem, from Rumi; 3-min Breathing Space MM |

| 6 | Mindful Communication and Thought Management | 15-min Body and Sound MM; Introduction to observation of and Non-identification to thoughts; Introduction to identifying and overcoming obstacles to mindful communication; 8-min MM on Sounds and Thoughts |

| 7 | Loving-kindness and Self-compassion | 8-min MM on Sounds and Thoughts; Introduction to Loving-kindness and usual misconceptions; 10-min Loving-Kindness Meditation; Try being kind to oneself in difficult situation. |

| 8 | Living wholeheartedly | 8-min MM on Sounds and Thoughts; Watching of “The Power of Vulnerability” from Brene Brown; Discussion about mindfulness, vulnerability, compassion, connection and courage to face oneself and others authentically; 10-min Mindful Walking Meditation |

| 9 | Tying concepts together | 15-min Body and Breath Meditation; Review of all mindfulness concepts and attitudes, mind management meditation; 15-min Mindful walking |

| 10 | 6-h Silent Retreat in one of Hangzhou’s Yoga Centers | Sitting meditation; Mindfulness Yoga; Body scan meditation; Mindful walking; Gratitude meditation |

| 11 | Using mindfulness at Work | 15 min Mindful Walking; Open discussion on how mindfulness could be used in careers as a mean of self-care and improved working environment |

| 12 | Keeping up with mindfulness training and conclusion | Sharing of resources and tips for continued mindfulness practice; STOP method; Body scan meditation |

Encouraged Weekly Practice (EWP) in each week.

Footnotes

Funding. This project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY16H090011) and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University from the Ministry of Education China.

References

- Allen A. P., Kennedy P. J., Cryan J. F., Dinan T. G., Clarke G. (2014). Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: focus on the trier social stress test. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 38 94–124. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaie M., Abbott R., Dunn B., Dickens C., Keil T. F., Henley W., et al. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 55 74–91. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Am V. D. V., Kuyken W., Wattar U., Crane C., Pallesen K. J., Dahlgaard J., et al. (2015). A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 37 26–39. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch J. J., Craske M. G. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav. Res. Ther. 44 1849–1858. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armony J. L., Dolan R. J. (2002). Modulation of spatial attention by fear-conditioned stimuli: an event-related fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 40 817–826. 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00178-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey N. W., Bridgman T. K., Marx W., Fitzgerald P. B. (2016). Asthma and mindfulness: an increase in mindfulness as the mechanism of action behind breathing retraining techniques? Mindfulness 7 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Berger I., Cassuto H. (2014). The effect of environmental distractors incorporation into a CPT on sustained attention and ADHD diagnosis among adolescents. J. Neurosci. Methods 222 62–68. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E., Prenger R., Taal E., Cuijpers P. (2010). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: a meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 68 539–544. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake C. A., Sauer-Zavala S., Boswell J. F., Gallagher M. W., Farchione T. J., Barlow D. H. (2016). Mindfulness-based exposure strategies as a transdiagnostic mechanism of change: an exploratory alternating treatment design. Behav. Ther. 47 225–238. 10.1016/j.beth.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittlebank A. D., Scott J., Williams J. M., Ferrier I. N. (1993). Autobiographical memory in depression: state or trait marker? Br. J. Psychiatry 162 118–121. 10.1192/bjp.162.1.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C., Conner K. O., Copeland V. C., Grote N., Beach S., Battista D., et al. (2010). Depression stigma, race, and treatment seeking behavior and attitudes. J. Community Psychol. 38 350–368. 10.1002/jcop.20368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell T. S., Labelle L. E., Bacon S. L., Faris P., Carlson L. E. (2012). Impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on attention, rumination and resting blood pressure in women with cancer: a waitlist-controlled study. J. Behav. Med. 35 262–271. 10.1007/s10865-011-9357-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson L. E., Brown K. W. (2005). Validation of the mindful attention awareness scale in a cancer population. J. Psychosom. Res. 58 29–33. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.04.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh K., Strauss C., Cicconi F., Griffiths N., Wyper A., Jones F. (2013). A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behav. Res. Ther. 51 573–578. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D. A., Schauenstein K. (2000). Mindful immunology: neuroimmunomodulation. Trends Immunol. 21 168–170. 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01577-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Gullone E., Allen N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: an integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29 560–572. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Gullone E., Hassed C., Knight W., Garvin T., Allen N. (2015). Mindful emotion regulation predicts recovery in depressed youth. Mindfulness 6 523–534. 10.1007/s12671-014-0284-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Lo B. C. Y., Allen N. B. (2008). The Impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect. Cogn. Ther. Res. 32 303–322. 10.1007/s10608-007-9119-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson F. J., Baxter A. J., Cheng H. G., Shidhaye R., Whiteford H. A. (2016). The burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in china and india: a systematic analysis of community representative epidemiological studies. Lancet 388 376–389. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30590-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Cui H., Zhou R., Jia Y. (2012). Revision of MIndful attention awareness scale(MAAS). Chinese J. Clin. Psychol. 20 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A., Calati R., Serretti A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? a systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31 449–464. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A., Serretti A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J. Altern. Complem. Med. 15 593–600. 10.1089/acm.2008.0495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A., Serretti A. (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 187 441–453. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt B. A., Risch N. J., Faris G., Friedman D., Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. (1988). The continuous performance test, identical pairs version (CPT-IP): i. new findings about sustained attention in normal families. Psychiatry Res. 26 223–238. 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90076-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R. J., Goleman D. J., Schwartz G. E. (1976). Attentional and affective concomitants of meditation: a cross-sectional study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 85 235–238. 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo M., Wilson K. A., Ong J., Koopman C. (2009). Mindfulness and rumination: does mindfulness training lead to reductions in the ruminative thinking associated with depression? Explore 5 265–271. 10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A., Lee K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science 333 959–964. 10.1126/science.1204529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S., Beck A., Felder J. N., Boggs J. M., Gallop R., Segal Z. V. (2014). Web-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for reducing residual depressive symptoms: an open trial and quasi-experimental comparison to propensity score matched controls. Behav. Res. Ther. 63 83–90. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan R. J. (2002). Emotion, cognition, and behavior. Science 298 1191–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger P. J. (1992). The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory, and Mental Dysfunction. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin P. R., Gross J. J. (2010). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion 10 83–91. 10.1037/a0018441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong P., Liang S., Carlton E. J., Jiang Q., Wu J., Wang L., et al. (2012). Urbanisation and health in china. Lancet 379 843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J., Strauss C., Bond R., Cavanagh K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? a systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 37 1–12. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge E. A., Bui E., Marques L., Metcalf C. A., Morris L. K., Robinaugh D. J., et al. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74 786–792. 10.4088/JCP.12m08083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hülsheger U. R., Alberts H. J. E. M., Feinholdt A., Lang J. W. B. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 98 310–325. 10.1037/a0031313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha A. P., Krompinger J., Baime M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 7 109–119. 10.3758/cabn.7.2.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junwon K., Youngsik L., Doughyun H., Kyungjoon M., Dohyun K., Changwon L. (2015). The utility of quantitative electroencephalography and integrated visual and auditory continuous performance test as auxiliary tools for the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126 532–540. 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabatzinn J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Practice 10 144–156. 10.1093/clipsy/bpg016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klee S. H., Garfinkel B. D. (1983). The computerized continuous performance task: a new measure of inattention. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 11 487–495. 10.1007/bf00917077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. K., Orsillo S. M. (2014). Investigating cognitive flexibility as a potential mechanism of mindfulness in generalized anxiety disorder. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 45 208–216. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever T. B., Strauss C., Cavanagh K., Jones F. (2014). The effectiveness of self-help mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in a student sample: a randomised controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 63 63–69. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E. K., Creswell J. D. (2017). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: monitor and acceptance theory (MAT). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51 48–59. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston C., Mcewen B. S., Casey B. J. (2009). Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 912–917. 10.1073/pnas.0807041106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A., Slagter H. A., Rawlings N. B., Francis A. D., Greischar L. L., Davidson R. J. (2009). Mental training enhances attentional stability: neural and behavioral evidence. J. Neurosci. 29 13418–13427. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1614-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers M., Makin C., Toms E., Thorberg F. A., Samios C. (2014). Trait Mindfulness in relation to emotional self-regulation and executive function. Mindfulness 5 619–625. 10.1007/s12671-013-0213-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macaskill A. (2013). The mental health of university students in the united kingdom. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 41 426–441. 10.1080/03069885.2012.743110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mankus A. M., Aldao A., Kerns C., Mayville E. W., Mennin D. S. (2013). Mindfulness and heart rate variability in individuals with high and low generalized anxiety symptoms. Behav. Res. Ther. 51 386–391. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoj S., Rush S. E. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review. J. Evid. Based Complem. Altern. Med. 19 271–286. 10.1177/2156587214543143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T., Greenberg M. T., Dariotis J. K., Gould L. F., Rhoades B. L., Leaf P. J. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 38 985–994. 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2018). National Education Career Development Statistical Report in 2017. Beijing: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K., Bradley B. P., De B. J., Painter M. (1997). Time course of attentional bias for threat information in non-clinical anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 35 297–303. 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00109-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morone N. E., Rollman B. L., Moore C. G., Qin L., Weiner D. K. (2016). A Mind–Body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: results of a pilot study. JAMA Int. Med. 176 329–337. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00746.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan J. A. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for older adults: effects on executive function. Neuropsychobiology 68 34–43. 10.1159/000350949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli D. M., Krech P. R., Holley L. C. (2005). Mindfulness training for elementary school students. J. Appl. School Psychol. 21 99–125. 10.1300/j370v21n01_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J. C., Manber R., Segal Z., Xia Y., Shapiro S., Wyatt J. K. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia. Sleep 37 1553–1563. 10.5665/sleep.4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romas J. A. (2009). Practical Stress Management. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig S., Reibel D. K., Greeson J. M., Brainard G. C., Hojat M. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction lowers psychological distress in medical students. Teach. Learn. Med. 15 88–92. 10.1207/s15328015tlm1502_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmertz S. K., Anderson P. L., Robins D. L. (2009). The relation between self-report mindfulness and performance on tasks of sustained attention. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 31 60–66. 10.1007/s10862-008-9086-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S. L., Brown K. W., Biegel G. M. (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 1 105–115. 10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Y., Ma Y., Fan Y., Feng H., Wang J., Feng S., et al. (2009). Central and autonomic nervous system interaction is altered by short-term meditation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 106 8865–8870. 10.1073/pnas.0904031106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Y., Ma Y., Wang J., Fan Y., Feng S., Lu Q., et al. (2007). Short-Term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 104 17152–17156. 10.1073/pnas.0707678104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Y., Posner M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16 213–225. 10.1038/nrn3916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Y., Yang L., Leve L. D., Harold G. T. (2012). Improving executive function and its neurobiological mechanisms through a mindfulness-based intervention: advances within the field of developmental neuroscience. Child Dev. Perspect. 6 361–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell P. D., Campbell J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: distinguishing rumination from reflection. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76 284–304. 10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lin W. (2000). POMS for use in China. Acta. Psychologica Sinica 32 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler M. S., Arnkoff D. B., Glass C. R. (2017). The neuroscience of mindfulness: how mindfulness alters the brain and facilitates emotion regulation. Mindfulness 8 1471–1478. 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. M., Teasdale J. D., Segal Z. V., Soulsby J. (2000). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 109 150–155. 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Yuan Y., Duan H., Qin S., Buchanan T. W., Kan Z., et al. (2014). Long-term academic stress increases the late component of error processing: An ERP study. Biol. Psychol. 99 77–82. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würtzen H., Dalton S. O., Elsass P., Sumbundu A. D., Steding-Jensen M., Karlsen R. V., et al. (2013). Mindfulness significantly reduces self-reported levels of anxiety and depression: results of a randomised controlled trial among 336 Danish women treated for stage I-III breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 49:1365. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Wang Y. Z., Liu X. H. (2015). Effectiveness of 8-week mindfulness training improving negative emotions. Chinese Mental Health J. 29 497–502 [Google Scholar]

- Yap M. B. H., Jorm A. F. (2011). The influence of stigma on young people’s help-seeking intentions and beliefs about the helpfulness of various sources of help. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 46 1257–1265. 10.1007/s00127-010-0300-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan F., Johnson S. K., Diamond B. J., David Z., Goolkasian P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: evidence of brief mental training. Conscious. Cogn. 19 597–605. 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B. L., Chan S., Liu T. B., Jin D., Hu C. Y., Hfk C. (2017). Mental health of the old- and new-generation migrant workers in China: who are at greater risk for psychological distress? Oncotarget. 8 59791–59799. 10.18632/oncotarget.15985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.