Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

We are grateful for the reviewers’ comments on version one. We have addressed the suggestions of David S. Stephens and Yih-Ling Tzeng on GC content (discussion paragraph 4), LPS function (introduction paragraph 2) and region A (discussion paragraph 7). We have also clarified our interpretation of the likelihood of N. weixii being a donor (results, last paragraph; discussion paragraph 2). The organisation of cps in N. subflava and N. weixii has been added to Figure 1, and discussed (results paragraph 1, discussion paragraph 5). In response to H. Steven Seifert, we have emphasised that consistency with the en bloc model does not indicate proof (discussion paragraph 5, abstract conclusions). We have also corrected typographical errors including where species names had not been introduced in full, and an incorrect reference (16).

Abstract

Background: Expression of a capsule from one of serogroups A, B, C, W, X or Y is usually required for Neisseria meningitidis ( Nme) to cause invasive meningococcal disease. The capsule is encoded by the capsule locus, cps, which is proposed to have been acquired by a formerly capsule null organism by horizontal genetic transfer (HGT) from another species. Following identification of putative capsule genes in non-pathogenic Neisseria species, this hypothesis is re-examined.

Methods: Whole genome sequence data from Neisseria species, including Nme genomes from a diverse range of clonal complexes and capsule genogroups, and non- Neisseria species, were obtained from PubMLST and GenBank. Sequence alignments of genes from the meningococcal cps, and predicted orthologues in other species, were analysed using Neighbor-nets, BOOTSCANing and maximum likelihood phylogenies.

Results: The meningococcal cps was highly mosaic within regions B, C and D. A subset of sequences within regions B and C were phylogenetically nested within homologous sequences belonging to N. subflava, consistent with HGT event in which N. subflava was the donor. In the cps of 23/39 isolates, the two copies of region D were highly divergent, with rfbABC’ sequences being more closely related to predicted orthologues in the proposed species N. weixii (GenBank accession number CP023429.1) than the same genes in Nme isolates lacking a capsule. There was also evidence of mosaicism in the rfbABC’ sequences of the remaining 16 isolates, as well as rfbABC from many isolates.

Conclusions: Data are consistent with the en bloc acquisition of cps in meningococci from N. subflava, followed by further recombination events with other Neisseria species. Nevertheless, the data cannot refute an alternative model, in which native meningococcal capsule existed prior to undergoing HGT with N. subflava and other species. Within-genus recombination events may have given rise to the diversity of meningococcal capsule serogroups.

Keywords: Neisseria, meningitis, capsule, recombination, horizontal genetic transfer, subflava

Introduction

Neisseria meningitidis ( Nme) is a gram-negative bacterium that typically establishes an asymptomatic colonisation of the human nasopharynx. Occasionally, Nme invades the bloodstream where, dependent on the possession of certain genetic factors and host-pathogen interactions, it is able to evade immune responses, causing invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) 1. IMD usually presents as meningitis and/or septicaemia, which have high mortality rates and are a public health priority in many jurisdictions. Certain clonal complexes (cc) of Nme, as determined by seven locus multi-locus sequence typing, represent genetic lineages commonly associated with IMD 2. Several genetic factors have been implicated in facilitating the disease phenotype. One factor that is necessary except in very rare cases 3– 5 is expression of a polysaccharide capsule belonging to one of serogroups A, B, C, W, X or Y 6, 7. A further six serogroups are not associated with disease 8.

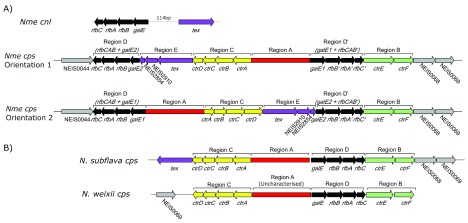

Expression of the meningococcal capsule is ABC transporter-dependent, and the genes required for capsule synthesis (region A) and export of the capsule (regions B and C) are consistently co-located in the chromosome in the capsule locus ( cps) 8. The capsule genogroup can be determined from region A sequences, enabling inference of the serogroup if capsule is expressed. Also co-located in cps is region D, which consists of galE and rfbABC, and region D’, a duplicated version of region D. The gene galE has been shown to be involved in LPS synthesis 9, and is also necessary for the synthesis of the capsule in serogroups E and Z 10, 11. There is dynamic inversion of genes within the capsule locus between galE1, and the truncated gene galE2, giving rise to two capsule orientations ( Figure 1A) 12. It has been noted that, since the cps is located 54 kb downstream of the origin of replication, it is possible that these inversions resolve collisions between transcription and genome replication machinery 12, as described in Escherichia coli 13, which may be important in regions where genes are highly expressed. Region E consists of the putative transcriptional accessory protein tex, a modification methyltransferase, and a truncated adenine-specific methyltransferase, none of which have been implicated in capsule synthesis 8. Flanking the 3’ end of region B is an additional hypothetical gene designated as NEIS0068 12.

Figure 1. Organisation of cps.

Organisation of genes within A) the two orientations of the meningococcal cps and B) the N. subflava and N. weixii cps.

There are several meningococcal ccs, including cc198, cc53, cc192, cc1117 and cc1136, that are consistently found to lack genes required for capsule synthesis. Isolates lacking a capsule are designated capsule null ( cnl) 14. Isolates of the Neisseria species most closely related to Nme, including N. gonorrhoeae, N. polysaccharea and N. lactamica are also consistently cnl 15. None of regions A, B, or C are found in these capsule null isolates, and they only possess one copy of region D.

The absence of a cps in the closest relatives of Nme led to the proposal that meningococcal cps may have been acquired as a result of a horizontal genetic transfer (HGT) event, resulting in the duplication of region D 12, 15, 16. A member of the Pasteurellacae family was proposed as a possible donor, based on sequence identity between capsule export genes in Pasteurella multocida and Nme 17. The recent discovery of capsule genes in non-pathogenic Neisseria species, including the human-associated species N. subflava, N. elongata and N. oralis, supported the more likely explanation that the capsule was lost from an ancestor of Nme, and then later reacquired from another Neisseria species 15. Nme is highly competent for transformation by HGT, and co-exists in the nasopharynx with many other Neisseria species, as well as bacteria from other genera. In addition to frequent recombination events within meningococcal populations, there have been several accounts of HGT from non-pathogenic Neisseria species to Nme, including genes associated with virulence and antibiotic resistance 18– 23.

The analysis reported here reveals a complex evolutionary history of meningococcal cps, involving multiple HGT events with other Neisseria species, one of which was likely N. subflava. The data reported are consistent with models hypothesising that the meningococcal capsule locus was acquired en bloc 12 by HGT into a capsule null organism.

Methods

Isolate collection

Meningococcal whole genome sequencing data (WGS) with good cps assembly were chosen from the Meningitis Research Foundation Meningococcus genome library (consisting of UK disease-associated isolates), the meningococcal 107 global collection project (consisting mostly of disease-associated isolates) 24, and a UK carriage dataset collected by the University of Oxford, all of which are available from https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/, hosted on the Bacterial Isolate Genome Sequence Database (BIGSdb) genomics platform 25. Meningococcal genomes were chosen at random from the datasets to provide up to one cc/genogroup combination from both carriage and disease where available. WGS from additional public pubMLST isolates M01-240355 26 and WUE2594 27 were chosen to include cc213 and cc5, respectively. Additional cps sequence data from isolates with capsule genogroup E, L, W, X or Z were retrieved from GenBank 28, originating from characterisation of meningococcal capsule serogroups 8.

WGS data from representative isolates of other Neisseria species were sourced from pubMLST, including the novel species Neisseria weixii (strain 10022, GenBank accession number CP023429.1). WGS from non- Neisseria species were sourced from GenBank and chosen for the presence of genes homologous with those within the meningococcal cps. including Actinobacillus succinogenes (strain 130Z, GenBank accession number CP000746.1), Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (AP76, CP001091.1), Aggregibacter actinomycetemcomitans (D11S-1, CP001733.2), Bibersteinia trehalosi (USDA-ARS-USMARC-189, CP006955.1), Vibrio vulnificus (NBRC 15645, CP012881.1), Glaesserella sp. (15-184, CP023057.1), Actinobacillus porcitonsillarum (9953L55, CP029206.1), Haemophilus influenzae (18010, FQ312006.1), Kingella kingae (KW1, LN869922.1) and Actinobacillus suis (NCTC12996, LT906456.1). The full isolate collection dataset is available as Extended data 29.

Speciation was confirmed using ribosomal multi-locus sequence typing (rMLST) 30. Loci defined within the rMLST scheme, with the exception of rpmE and rpmJ, which are duplicated in some Neisseria, were extracted and aligned with MAFFT 31 within the BIGSdb genome comparator module. TrimAl 32 was used to remove sites with gaps in more than 10% of sequences. A neighbor-joining tree was generated with the Jukes-Cantor 33 substitution model using phangorn (v2.4.0) 34 implemented in R, and rooted at the mid-point.

Annotation of capsule loci

The majority of the Neisseria WGS in pubMLST had previously been fully annotated manually for cps genes rfbABC (NEIS0045-7), galE (NEIS0048), tex (NEIS0059), the pseudo-methyltransferases NEIS2854 and NEIS2910 , ctrABCDEF (NEIS0055-8), and flanking genes NEIS0044, NEIS0068 and NEIS0069, where present. Genomes in which one or more of these genes had not been annotated were queried using the BLASTn-based scanning tool in pubMLST; if a relevant gene was identified, this was tagged in the WGS data and an appropriate allele designation set. Nme sequences from GenBank had a fully annotated cps 8. Predicted orthologues of cps genes were identified in non- Neisseria species using BLASTn.

The meningococcal genomes possessing a capsule were investigated to determine whether the capsule locus was in orientation 1 (-NEIS0044-><- rfbCAB-<- galE2-<-Region E-<-Region C--Region A-- galE1->- rfbBAC’->-Region B->-NEIS0068->-NEIS0069->) or orientation 2 (-NEIS0044-><- rfbCAB-<- galE1—Region A—Region C->-Region E->- galE2->- rfbBAC’->-Region B->-NEIS0068->-NEIS0069->) ( Figure 1A). galE1/2 were distinguished according to the nomenclature used by Bartley et al. 12, in which the truncated form of galE within cps was designated galE2, and the full length form within cps as galE1. If the capsule locus spanned more than one assembled contig, the orientation was assumed based on the co-localisation of the relevant genes and regions.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Gene sequences were exported from pubMLST from meningococcal and non-meningococcal Neisseria WGS. Sequences were downloaded manually from GenBank from non- Neisseria. Amino acid sequences were deduced in MEGA X 35 and aligned using Muscle 36, correcting for frameshift mutations where applicable, and manually trimmed to give a final nucleotide sequence alignment.

Aligned nucleotide sequences of region C genes ctrABCD, region B genes ctrEF, and rfbABC, or predicted homologues, were concatenated separately. Full length galE/galE1 orthologues were also analysed separately. Each concatenated set of sequences was loaded into SplitsTree4 (v4.14.9) 37 and a phylogenetic network was deduced using the neighbor-net algorithm 38. Groups were identified based on a balance between maximising edge weighting, whilst minimising contradictory splits.

Sequences from meningococcal isolates CA41967, Z2491, α707, WUE171 and 1.02397.V were chosen for further investigation of the whole capsule locus and its flanking regions, and compared to sequences from ST42119 (capsule null Nme), NJ9703 ( N. subflava) and 10022 ( N. weixii), with USDA-ARS-USMARC-188 ( B. trehalosi) included as an outgroup. Aligned nucleotide sequences of rfbCAB+galE2, ctrDCBA, rfbBAC’+galE1, ctrEF, and NEIS0069 (where sequenced), were concatenated separately, since capsule null Nme does not contain ctrDCBA or ctrEF; gene sequences were orientated to be in the same direction as they would be relative to NEIS0044 in orientation 1 of the meningococcal cps ( Figure 1A), where NEIS0044 is in the forward orientation. Each concatenated set of sequences was loaded into the Recombination Detection Programme 4 39. Recombination was assessed in each cps + meningococcal isolate using manual BOOTSCANing 40, with capsule null Nme, N. subflava, N. weixii and B. trehalosi as reference sequences. Neighbor-joining trees were used with the Jukes-Cantor substitution model and 100 bootstraps. Bootstrap support below 70% was disregarded. In order to minimise false breakpoints that may occur due to high sequence identity, appropriate window size was determined by testing CA40160, CA41628 and GL40098 (capsule null Nme), and OX42005 ( N. subflava), which were not expected to have recombinant capsule sequences. Window size was set at 400 bp for rfbABC+ galE1/2, 200 bp for ctrDCBA and ctrEF, and 250 bp for NEIS0069. Step size was set at 10% of window size.

Aligned nucleotide sequences of ctrEF, less the first 774 bp of ctrE, which were suspected to be recombinant, were concatenated. A maximum likelihood phylogeny of Neisseria sequences, with B. trehalosi as an outgroup, was generated in PhyML (v3.1) 41 with 100 bootstraps, using the GTR+I+G substitution method 42, determined to be the best fit by jModelTest (v2.1.10) 43. A second phylogeny was generated in the same way using aligned ctrD nucleotide sequences that were suspected to be non-recombinant.

Results

Species confirmation and annotations

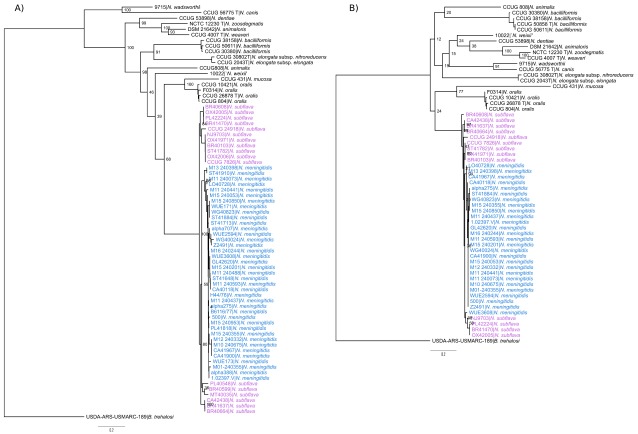

Designated species names matched their position in a phylogeny based on rMLST, with sequences from all Neisseria isolates belonging to a single clade ( Figure 2). The distribution of capsule export genes ctrABCDEF, region D genes rfbABC + galE and NEIS0059 was consistent with previous descriptions 8, 15, and all 11 genes were also annotated in the proposed species N. weixii, which was also observed to contain homologues of the putative region A from the N. animalis cps ( Figure 1B). Additionally, the 345 bp pseudo-methyltransferase NEIS2854 was present within all cps + meningococci, as well as the capsule null strain ST42119 (cc198); NEIS2854 is a truncated version of the 1008 bp gene NEIS2725, which was only present in WGS from N. gonorrhoeae isolates and one N. polysaccharea isolate (CCUG 4790) only. The pseudo-methyltransferase NEIS2910 was present in all cps + Nme, ST42119, N. gonorrhoeae and CCUG 4790 genomes. The hypothetical gene NEIS0068, which flanks region B of the capsule locus, was identified within genomes from all cps + Nme and N. subflava isolates, but no other Neisseria species or capsule null meningococci. The organisation of the N. subflava cps was described previously 15 ( Figure 1B).

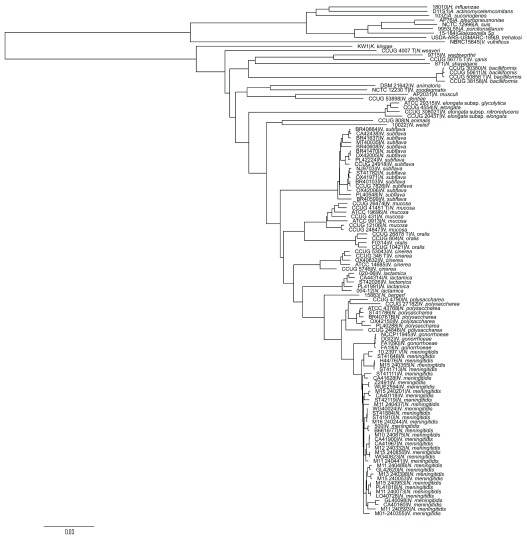

Figure 2. Species phylogeny.

Neighbor-joining tree using the Jukes-Cantor substitution model, generated from concatenated, aligned rMLST nucleotide sequences.

Regions B and C of the meningococcal cps are mosaic

Phylogenetic analyses of meningococcal cps regions B and C, along with predicted orthologues from other Neisseria species and proteobacteria, were consistent with the presence of recombinant sequences in the meningococcal cps.

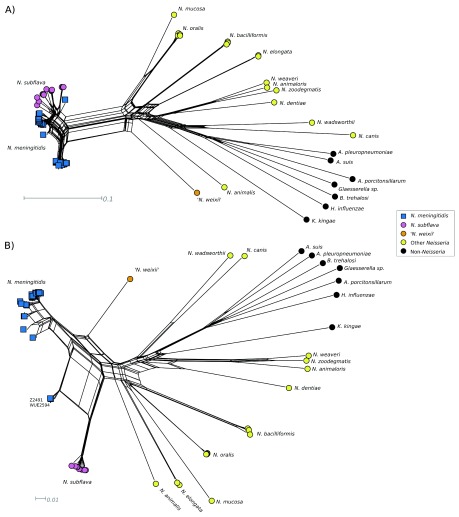

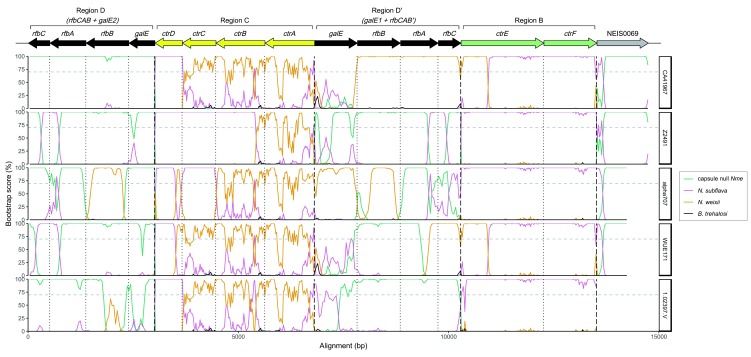

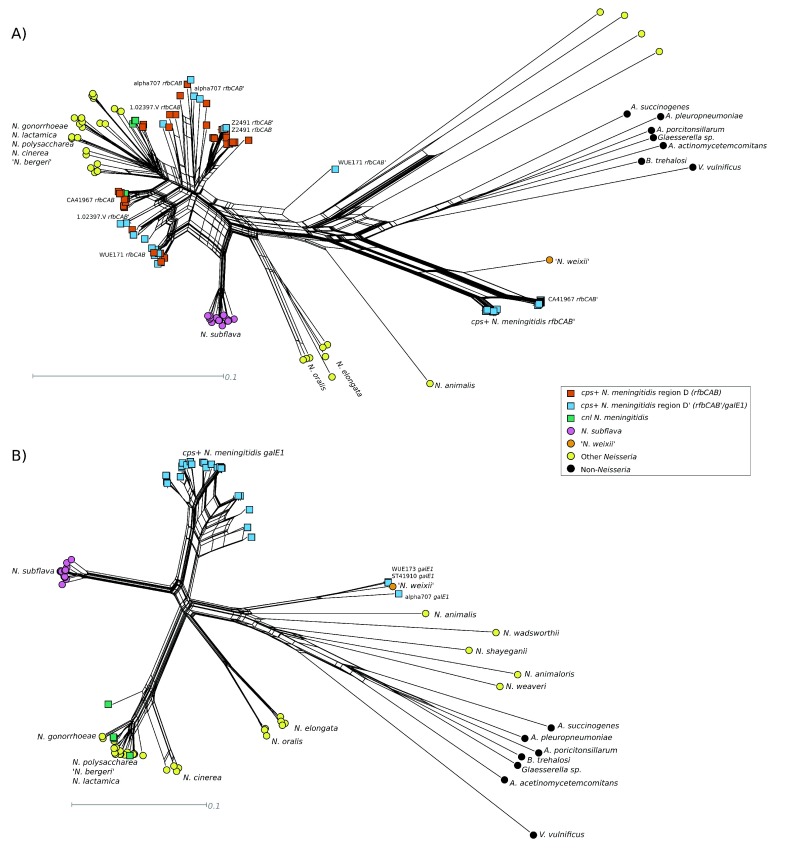

Neighbor-net analysis revealed a well-supported split that grouped region B sequences from meningococci and N. subflava together ( Figure 3A). There was also some support for a contradictory split grouping region B sequences from 24 of the meningococci with N. weixii. BOOTSCANing in 200 bp windows of CA41967, one of the 24, was consistent with a mosaic Region B in the cps, with at least the first 774 bp of ctrE having support for N. weixii as the nearest neighbour grouping, before switching to N. subflava ( Figure 4).

Figure 3. Region B and C neighbor-nets.

Neighbor nets generated using concatenated, aligned nucleotide sequences of ( A) region B and ( B) region C genes. Edges represent splits that support the separation of two clusters in the network, with the length of the line representing the weight of the split. Increasing number of parallel edges represents contradictory splits.

Figure 4. BOOTSCANs of cps.

Recombination analysis of chosen cps sequences from CA41967, Z2491, α707, WUE171 and 1.02397.V by BOOTSCANing, with ST42119 (capsule null Nme), NJ9703 ( N. subflava), 10022 ( N. weixii) included as potential parent sequences, and USDA-ARS-USMARC-189 ( B. trehalosi) included as an outgroup. Vertical short dashed lines represent gene boundaries, and vertical long dashed lines represent separate analyses.

A neighbor-net generated from region C sequences contained several contradictory splits that either grouped meningococcal region C sequences with N. subflava or the proposed species N. weixii, both with high support relative to the rest of the network. There was no well-supported split clustering all three into a single group ( Figure 3B). This was corroborated by BOOTSCANing of representative isolates: all five cps sequences scanned had good bootstrap support for N. subflava as the nearest neighbour grouping for at least the first 440 bp of region C (at the 3’ end of ctrD) ( Figure 4). Across the rest of the region, there was greater bootstrap support for N. weixii as the nearest neighbour, although the signal was noisy. In Z2491, the signal for N. subflava extended for 2379 bp (comprising ctrD, ctrC and much of ctrB) before switching to N. weixii. This was consistent with a relatively highly weighted neighbor-net split which grouped Z2491, as well as WUE2594, with N. subflava.

Meningococcal capsule export sequences are nested within homologous sequences in N. subflava

A maximum likelihood phylogeny of region B, excluding the first 774 bp of ctrE, which was determined by BOOTSCANing to be potentially recombinant in some WGS, revealed that region B sequences from meningococci are nested within homologous sequences from N. subflava ( Figure 5A). The diversity of these sequences was much lower in Nme (mean p-distance 0.017) than N. subflava (mean p-distance 0.040). Similarly, suspected non-recombinant ctrD sequences from meningococci were nested within predicted homologous sequences belonging to N. subflava ( Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Region B and ctrD phylogenies.

Maximum likelihood phylogenies using the GTR+I+G substitution model, generated from concatenated, aligned nucleotide sequences of ( A) region B genes ctrEF (NEIS0066 was trimmed at the 5’ end to remove potentially recombinant sequences) and ( B) ctrD. In both phylogenies, B. trehalosi was included as an outgroup; Nme blue, N. subflava pink.

Region D’ of the cps locus is not a duplication of meningococcal region D

As described previously 12, the meningococcal genomes possessed the cps locus in either the (-NEIS0044-><- rfbCAB-<- galE2-<-Region E-<-Region C--Region A-- galE1->- rfbBAC’->-Region B->-NEIS0068->-NEIS0069->) orientation, or the (-NEIS0044-><- rfbBAC-<- galE1—Region A—Region C->-Region E->- galE2->- rfbBAC’->-Region B->-NEIS0068->-NEIS0069->) orientation ( Figure 1A). galE1 was distinguished from galE2 by the fact that the latter is consistently truncated at the 5’ end.

Phylogenetic analyses of rfbABC’, along with predicted orthologues from other Neisseria species and proteobacteria, were consistent with acquisition of rfbABC’ sequences by HGT from another Neisseria species ( Figure 6A). In WGS from 23 isolates, neighbor-net splits supported the grouping of rfbABC’ with homologous sequences from the novel species N. weixii. This relationship was further supported by BOOTSCANing of concatenated rfbBAC’ sequences from CA41967, which showed high bootstrap support for N. weixii as the nearest neighbour grouping across most of the region ( Figure 4). There was a drop in bootstrap support for any reference sequence across galE1, possibly indicating the absence of a good representative reference sequence. An appropriate sequenced reference could not be identified using a neighbour-net generated from aligned galE, galE1 and predicted orthologues ( Figure 6B), or by searching the NCBI nucleotide collection. galE1 sequences from α707 (serogroup E), WUE173 (serogroup Z) and ST41910 (serogroup Z) grouped with predicted orthologous sequences in N. weixii, consistent with BOOTSCANing analyses of α707 ( Figure 4).

Figure 6. Region D neighbor-nets.

Neighbor nets generated using concatenated, aligned nucleotide sequences of ( A) rfbABC genes, with both rfbABC and rfbABC’ extracted from cps+ meningococci, and ( B) full length galE or galE1 (truncated galE2 alleles not included).

There were no highly weighted splits supporting the grouping of the sequences from the remaining 16 isolates with any other species, and a high degree of reticulation was present within the neighbor-net, which can be indicative of recombination ( Figure 6A). This was consistent with BOOTSCANing results in sequences from chosen isolates ( Figure 4). Z2491 rfbBAC’ + galE1 contained sequences similar to both capsule null Nme and N. subflava. α707 and WUE171 rfbBAC’ contained sequences similar to both Nme and N. weixii, with a drop off in bootstrap support within WUE171 sequences across galE1. The 1.02397.V rfbBAC’ sequences were similar to capsule null Nme, again with a drop-off in bootstrap support for any reference across galE1.

Neighbor-net analysis of rfbABC sequences contained a split supporting the grouping of the concatenated sequences with capsule null meningococci, but again there was a lot of reticulation ( Figure 6A). Sequences from chosen isolates were investigated further using BOOTSCANing. BOOTSCAN results of rfbABC + galE2 sequences from Z2491 and WUE171 were consistent with a recombination event involving N. subflava ( Figure 4). In 1.02397.V, there was only bootstrap support for capsule null Nme, although there was a drop-off in bootstrap support through parts of rfbB and galE2. α707 rfbABC + galE2 sequences were grouped with the capsule null group according to the split, but mosaic signals were identified in the sequences consistent with a recombination event involving a species more closely related to N. weixii. CA41967 specifically clustered with capsule null rfbABC sequences, consistent with BOOTSCANs which did not demonstrate recombination in this region.

Discussion

In this analysis, evidence is presented that is consistent with a donation of capsule export gene sequences from N. subflava to the meningococcal cps, as has been previously postulated 15. Following the identification of recombinant sequence data ( Figure 3 and Figure 4), further analyses demonstrated that non-recombinant tracts within regions B and C were phylogenetically nested within homologous N. subflava sequences ( Figure 5). This phylogenetic pattern would only be expected to occur if the true donor was a member of N. subflava, rather than another species closely related to N. subflava. HGT is more likely to occur between closely related species, since higher sequence identity facilitates homologous recombination. N. subflava is also widely carried by humans, and it has previously been suggested that strains of the close relative of Nme, N. gonorrhoeae, may have acquired penA genes associated with antimicrobial resistance from N. subflava through HGT 44. The tissue tropism of the Nme and N. subflava are slightly different, with N. subflava isolated more commonly from the buccal cavity than the nasopharynx 45, but both are frequently isolated from carriage studies using pharyngeal swabs 46, 47. Therefore, HGT of cps sequences between N. subflava and Nme is biologically conceivable.

Sequence analyses indicate that a second species donated sequences within region C of all meningococci analysed, and region B of several meningococcal isolates, resulting in mosaic loci ( Figure 3 and Figure 4). If any region B or C sequences were acquired by the meningococcus by descent, they could not be identified in these sequence analyses ( Figure 4). The novel species N. weixii 48 was identified as a possible candidate ( Figure 3 and Figure 4), described as being isolated from the Tibetan Plateau Pika ( Ochotona curzoniae) in the Qinghai Province, China (GenBank accession CP023429.1). This isolate contained sequences homologous to the N. animalis putative region A between its region C and region D homologues ( Figure 1B). Epidemiological interaction between N. weixii and Nme is unlikely, since the pika is a member of the Lagomorpha found in alpine meadows. Analyses by rMLST ( Figure 2) indicate that the next closest species is the guinea pig-associated species N. animalis; all sequenced human-associated species are relatively distantly related. An as-yet-unidentified human-associated Neisseria species more closely related to N. weixii could be the donor of these sequences.

In many of the meningococcal genomes analysed, results were also consistent with HGT of duplicated region D sequences. In these genomes, rfbABC’+ galE1 sequences were divergent from rfbABC+ galE sequences belonging to capsule null meningococci, either in whole or in part ( Figure 6A). BOOTSCANing analyses were consistent with either N. subflava or something related to N. weixii being the candidate donor of the divergent rfbBAC’ sequences ( Figure 4). The galE1 sequences of α707 (cc254, genogroup E), ST41910 (cc1157, genogroup Z) and WUE173 (genogroup Z) also clustered with N. weixii ( Figure 6B). In all other meningococcal genomes, galE1 was divergent from N. subflava, N. weixii and capsule null Nme, and the donor of this sequence may be an as yet unidentified Neisseria species ( Figure 6B). The divergence between galE1, galE2 and capsule null galE sequences, including genogroup E and Z outliers, has been described previously by Bartley et al. 12. In the same study, it was also demonstrated that galE is bi-functional, synthesising UDP-galactose and UDP-galactosamine, and galE2 is a truncated gene closely related to galE. galE1 was determined to be predominantly mono-functional, producing only UDP-galactose, but bi-functional in genogroups Z and E, which require this bi-functionality for capsule synthesis. The current study has so far discussed evidence indicating that the meningococcal cps is highly mosaic, having undergone HGT with as many as three other Neisseria species, but Bartley et al. go further, proposing that the phylogenetic distribution and functionality of galE1 and galE2 could be explained by the process of an en bloc transfer of the entire capsule locus from a donor species into modern meningococcal clones 12.

The hypothesis that the meningococcal cps was acquired de novo by a previously capsule null meningococcal recipient, as a result of a HGT event, has been proposed several times 12, 15– 17, 49. Such an event would have had important consequences on the epidemiology of Nme, since the possession of a capsule is almost always necessary for IMD 6, 7. The existence of the H. influenzae capsule has also invoked HGT from another species. Similarly to Nme, H. influenzae consists of variants both with and without a capsule; the capsule locus cap was proposed to have been donated by HGT from Haemophilus sputorum, although H. sputorum may actually be a member of another genus from the Pasteurellacae family 50. The low GC content of region A of the capsule locus has also been cited as evidence that the capsule may have been acquired by HGT 8, 51, but this has also been observed in the capsule synthesis region of other Neisseria species 15, as well as E. coli, H. sputorum and A. pleuropneumoniae 52– 54. Therefore, GC content may not directly inform on the recent evolutionary history of the meningococcal capsule. The sequence identity between capsule export sequences in Nme and P. multocida formed the basis of a hypothesis invoking donation of the capsule by a member of the Pasteurellacae family, in the absence of further Neisseria WGS data at the time 17. More recent data demonstrate that capsule export gene sequences are more closely related to homologous sequences from non-pathogenic Neisseria species 15 ( Figure 3), which raises the question as to whether the capsule was simply inherited by descent. The rationale for a de novo acquisition of capsule into a capsule null clone was presented based on the distribution of capsule genes throughout the Neisseria genus, with capsule genes not having been identified in any isolates of the species most closely related to Nme: N. gonorrhoeae, N. polysaccharea, N. lactamica, N. cinerea and ` N. bergeri’, which may have resulted from a loss of capsule in a common ancestor of these species, followed by reacquisition in Nme 15.

The validity of the en bloc acquisition model has been further tested using a genome dataset containing a wide diversity of meningococcal clonal complexes and capsule genogroups. BOOTSCANing analyses consistently support N. subflava as the nearest neighbour grouping at both ends of the capsule locus, and perhaps into NEIS0069 ( Figure 4). The en bloc model also postulates that the donor capsule locus was arranged <-NEIS0059-<-Region C-Region A->-Region D->-NEIS0068->-NEIS0069-> 12, which is the same arrangement as characterised in N. subflava 15, and the flanking gene NEIS0068 has only been found in cps + meningococci and N. subflava. The arrangement of orientation 1 of the meningococcal cps and the N. subflava cps between tex and NEIS0069 is equivalent ( Figure 1). These observations are consistent with, but not proof of, an en bloc donation of capsule from N. subflava, as opposed to a member of another genus, to a capsule null meningococcal clone, with subsequent recombination events with at least two other species.

An alternative explanation is that a duplication of meningococcal region D, and perhaps the whole capsule locus, previously existed in the recipient organism. This alternative explanation could account for the fact that some isolates still contain sequences resembling capsule null meningococci in region D’ ( Figure 4 and Figure 6A). This may be explained by dynamic inversions of the capsule locus ( Figure 1A) 12. If inversions involve multiple recombination events with different break points, sequences within the two regions could become unlinked, making it difficult to trace their evolutionary history, and erasing evidence of an acquisition event within region D’ sequences. This problem is exacerbated by capsule switching that occurs between meningococcal clones, wherein HGT events do not necessarily involve the capsule locus in its entirety 55. With these issues, by the nature of the question 56, and the relatively small size of WGS datasets compared to global Neisseria populations through time, it would be difficult to prove beyond doubt that the meningococcal capsule was acquired de novo by a capsule null clone, unless a meningococcal isolate were identified with a complete N. subflava capsule locus, requiring an absence of further recombination events. Unravelling the complete evolutionary process that led to the modern-day cps may not be possible using only contemporary meningococcal genomes.

An outstanding question concerns the origins of region A. Neither N. weixii nor N. subflava possess putative region A sequences that are highly comparable to those found in meningococcal capsule serogroups, although they do share some homologous sequences. Recombination events that include region A capsule synthesis genes, which result in capsular serogroup switching, have been repeatedly observed within meningococcal populations 55, 57, 58. The results presented here raise the question as to whether meningococcal serogroup diversity may have arisen through capsule switching with other species. The serogroup B capsule is structurally equivalent to that of E. coli K1, Mannheimia haemolytica A2 and Moraxella nonliquifaciens 59. There is homology between the synthesis regions of these capsules 60, but amino acid sequence identity above 70% has not been reported, and sequence data did not show evidence of non- Neisseria sequences having been donated to region C or region D ( Figure 3, Figure 4). galE1 sequence clustering indicate that an un-sequenced Neisseria species may have donated sequences to Nme ( Figure 6B). It may be informative to characterise putative region A homologues of any new species identified, which may shed further light on this question.

In conclusion, WGS data are consistent with a model whereby the meningococcal capsule locus was acquired by a capsule null meningococcal clone en bloc in a HGT event from a single donor, most likely N. subflava. Subsequent homologous recombination events with at least two other species resulted in a highly mosaic locus. Nevertheless, these data are insufficient to rule out an alternative model, in which native meningococcal capsule existed prior to undergoing HGT with N. subflava and other species. It is possible that serogroup diversity of meningococcal populations increased as a result of cross-species HGT events. Characterisation of putative capsule genes of newly isolated Neisseria species, particularly those isolated from humans, may provide new insights into the complex evolutionary history of the meningococcal capsule locus.

Data availability

Underlying data

Details on the sequences of isolates used in the present study, obtained from PubMLST and GenBank, are available as Extended data.

Extended data

Figshare: Isolates used in "Neisseria meningitidis has acquired sequences within the capsule locus by horizontal genetic transfer". https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8256572.v1 29.

This project contains the full list of isolates used in this study, along with associated metadata, and pubMLST ID and/or accession number.

Extended data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Acknowledgements

This publication made use of: the Neisseria Multi Locus Sequence Typing website ( https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) sited at the University of Oxford (developed by Jolley et al. 29). The development of this site has been funded by the Wellcome Trust and European Union. This publication made use of the Meningitis Research Foundation Meningococcus Genome Library ( https://pubmlst.org/bigsdb?db=pubmlst_neisseria_mrfgenomes) developed by Public Health England, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the University of Oxford as a collaboration, and funded by Meningitis Research Foundation.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust (109025 and 087622).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, et al. : Meningococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1378–88. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, et al. : Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(6):3140–5. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Findlow H, Vogel U, Mueller JE, et al. : Three cases of invasive meningococcal disease caused by a capsule null locus strain circulating among healthy carriers in Burkina Faso. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(7):1071–7. 10.1086/512084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ganesh K, Allam M, Wolter N, et al. : Molecular characterization of invasive capsule null Neisseria meningitidis in South Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):40. 10.1186/s12866-017-0942-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johswich KO, Zhou J, Law DK, et al. : Invasive potential of nonencapsulated disease isolates of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 2012;80(7):2346–53. 10.1128/IAI.00293-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coureuil M, Join-Lambert O, Lécuyer H, et al. : Pathogenesis of meningococcemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(6): pii: a012393. 10.1101/cshperspect.a012393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Deuren M, Brandtzaeg P, Van Der Meer JW: Update on meningococcal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(1):144–66. 10.1128/cmr.13.1.144-166.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrison OB, Claus H, Jiang Y, et al. : Description and nomenclature of Neisseria meningitidis capsule locus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(4):566–73. 10.3201/eid1904.111799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hammerschmidt S, Birkholz C, Zähringer U, et al. : Contribution of genes from the capsule gene complex (cps) to lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis and serum resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11(5):885–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhattacharjee AK, Jennings HJ, Kenny CP: Structural elucidation of the 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid containing meningococcal 29-e capsular polysaccharide antigen using carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 1978;17(4):645–51. 10.1021/bi00597a013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bundle DR, Smith IC, Jennings HJ: Determination of the structure and conformation of bacterial polysaccharides by carbon 13 nuclear magnetic resonance. Studies on the group-specific antigens of Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A and X. J Biol Chem. 1974;249(7):2275–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bartley SN, Mowlaboccus S, Mullally CA, et al. : Acquisition of the capsule locus by horizontal gene transfer in Neisseria meningitidis is often accompanied by the loss of UDP-GalNAc synthesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7: 44442. 10.1038/srep44442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ivanova D, Taylor T, Smith SL, et al. : Shaping the landscape of the Escherichia coli chromosome: replication-transcription encounters in cells with an ectopic replication origin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(16):7865–77. 10.1093/nar/gkv704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Claus H, Maiden MC, Maag R, et al. : Many carried meningococci lack the genes required for capsule synthesis and transport. Microbiology. 2002;148(Pt 6):1813–9. 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clemence MEA, Maiden MCJ, Harrison OB: Characterization of capsule genes in non-pathogenic Neisseria species. Microb Genomics. 2018;4(9):e000208. 10.1099/mgen.0.000208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu Z, Du P, Zhu B, et al. : Phylogenetic study of clonal complex (CC)198 capsule null locus ( cnl) genomes: A distinctive group within the species Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;34:372–7. 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schoen C, Blom J, Claus H, et al. : Whole-genome comparison of disease and carriage strains provides insights into virulence evolution in Neisseria meningitidis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(9):3473–8. 10.1073/pnas.0800151105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spratt BG, Bowler LD, Zhang QY, et al. : Role of interspecies transfer of chromosomal genes in the evolution of penicillin resistance in pathogenic and commensal Neisseria species. J Mol Evol. 1992;34(2):115–25. 10.1007/BF00182388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu P, Klutch MJ, Bash MC, et al. : Genetic diversity of three lgt loci for biosynthesis of lipooligosaccharide (LOS) in Neisseria species. Microbiology. 2002;148(Pt 6):1833–44. 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qvarnstrom Y, Swedberg G: Variations in gene organization and DNA uptake signal sequence in the folP region between commensal and pathogenic Neisseria species. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:11. 10.1186/1471-2180-6-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Linz B, Schenker M, Zhu P, et al. : Frequent interspecific genetic exchange between commensal Neisseriae and Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(5):1049–58. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marri PR, Paniscus M, Weyand NJ, et al. : Genome sequencing reveals widespread virulence gene exchange among human Neisseria species. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11835. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wörmann ME, Horien CL, Bennett JS, et al. : Sequence, distribution and chromosomal context of class I and class II pilin genes of Neisseria meningitidis identified in whole genome sequences. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:253. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bratcher HB, Corton C, Jolley KA, et al. : A gene-by-gene population genomics platform: de novo assembly, annotation and genealogical analysis of 108 representative Neisseria meningitidis genomes. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1138. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ: Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Budroni S, Siena E, Dunning Hotopp JC, et al. : Neisseria meningitidis is structured in clades associated with restriction modification systems that modulate homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(11):4494–9. 10.1073/pnas.1019751108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schoen C, Weber-Lehmann J, Blom J, et al. : Whole-genome sequence of the transformable Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strain WUE2594. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(8):2064–5. 10.1128/JB.00084-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, et al. : GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;41(Database issue):D36–42. 10.1093/nar/gks1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clemence M: Isolates used in "Neisseria meningitidis has acquired sequences within the capsule locus by horizontal genetic transfer". figshare. Dataset. 2019. 10.6084/m9.figshare.8256572.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jolley KA, Bliss CM, Bennett JS, et al. : Ribosomal multilocus sequence typing: universal characterization of bacteria from domain to strain. Microbiology. 2012;158(Pt 4):1005–15. 10.1099/mic.0.055459-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, et al. : MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–66. 10.1093/nar/gkf436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T: trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1972–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jukes TH, Cantor CR: Evolution of Protein Molecules. Mammalian Protein Metabolism III. Academic Press;1969;21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schliep KP: phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(4):592–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, et al. : MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–9. 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edgar RC: MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huson DH, Bryant D: Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(2):254–67. 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bryant D, Moulton V: Neighbor-net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21(2):255–65. 10.1093/molbev/msh018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, et al. : RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1(1): vev003 10.1093/ve/vev003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Salimen MO, Carr JK, Burke DS, et al. : Identification of breakpoints in intergenotypic recombinants of HIV type 1 by bootscanning. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11(11):1423–5. 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, et al. : New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307–21. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lanave C, Preparata G, Saccone C, et al. : A new method for calculating evolutionary substitution rates. J Mol Evol. 1984;20(1):86–93. 10.1007/BF02101990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, et al. : jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):772. 10.1038/nmeth.2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Furuya R, Onoye Y, Kanayama A, et al. : Antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of Neisseria subflava from the oral cavities of a Japanese population. J Infect Chemother. 2007;13(5):302–4. 10.1007/s10156-007-0541-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Donati C, Zolfo M, Albanese D, et al. : Uncovering oral Neisseria tropism and persistence using metagenomic sequencing. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(7): 16070. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Diallo K, Trotter C, Timbine Y, et al. : Pharyngeal carriage of Neisseria species in the African meningitis belt. J Infect. 2016;72(6):667–77. 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Díaz J, Cárcamo M, Seoane M, et al. : Prevalence of meningococcal carriage in children and adolescents aged 10-19 years in Chile in 2013. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9(4):506–15. 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang G, Yang J, Lai XH, et al. : Neisseria weixii sp. nov., isolated from rectal contents of Tibetan Plateau pika ( Ochotona curzoniae). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019. 10.1099/ijsem.0.003466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bennett JS, Bentley SD, Vernikos GS, et al. : Independent evolution of the core and accessory gene sets in the genus Neisseria: insights gained from the genome of Neisseria lactamica isolate 020-06. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1):652. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nielsen SM, de Gier C, Dimopoulou C, et al. : The capsule biosynthesis locus of Haemophilus influenzae shows conspicuous similarity to the corresponding locus in Haemophilus sputorum and may have been recruited from this species by horizontal gene transfer. Microbiology. 2015;161(6):1182–8. 10.1099/mic.0.000081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Claus H, Vogel U, Mühlenhoff M, et al. : Molecular divergence of the sia locus in different serogroups of Neisseria meningitidis expressing polysialic acid capsules. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;257(1):28–34. 10.1007/pl00008618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clarke BR, Pearce R, Roberts IS: Genetic organization of the Escherichia coli K10 capsule gene cluster: identification and characterization of two conserved regions in group III capsule gene clusters encoding polysaccharide transport functions. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(7):2279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nielsen SM, de Gier C, Dimopoulou C, et al. : The capsule biosynthesis locus of Haemophilus influenzae shows conspicuous similarity to the corresponding locus in Haemophilus sputorum and may have been recruited from this species by horizontal gene transfer. Microbiology. 2015;161(6):1182–8. 10.1099/mic.0.000081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ito H: The genetic organization of the capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis region of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 14. J Vet Med Sci. 2015;77(5):583–6. 10.1292/jvms.14-0174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mustapha MM, Marsh JW, Krauland MG, et al. : Genomic Investigation Reveals Highly Conserved, Mosaic, Recombination Events Associated with Capsular Switching among Invasive Neisseria meningitidis Serogroup W Sequence Type (ST)-11 Strains. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(6):2065–75. 10.1093/gbe/evw122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Aravind L: Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes: quantification and classification. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:709–42. 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Swartley JS, Marfin AA, Edupuganti S, et al. : Capsule switching of Neisseria meningitidis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(1):271–6. 10.1073/pnas.94.1.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Beddek AJ, Li MS, Kroll JS, et al. : Evidence for capsule switching between carried and disease-causing Neisseria meningitidis strains. Infect Immun. 2009;77(7):2989–94. 10.1128/IAI.00181-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Willis LM, Whitfield C: Structure, biosynthesis, and function of bacterial capsular polysaccharides synthesized by ABC transporter-dependent pathways. Carbohydr Res. 2013;378:35–44. 10.1016/j.carres.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Frosch M, Edwards U, Bousset K, et al. : Evidence for a common molecular origin of the capsule gene loci in gram-negative bacteria expressing group II capsular polysaccharides. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5(5):1251–63. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]