Abstract

Peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) is a reactive, inflammatory, hyperplastic soft tissue growth of the gingiva. Lesions are usually labial and small with an anterior maxillary presentation, occurring commonly in the younger population. We present an unusual case of a large POF in a 68-year-old woman that presented on the posterior palate with a unique radiographic appearance. Various differential diagnoses of POF and such palatal lesions, etiopathogenesis of POF, and the surgical management of these lesions have been discussed in detail. Close post-operative follow-up of these lesions is mandatory due to the high recurrence rates.

Keywords: Excisional biopsy, fibroma, gingival diseases, maxilla, ossifying fibroma, palate

Introduction

A non-ulcerated, smooth mucosal swelling on the hard palate can present a challenge to the diagnostician. Most of these lesions are innocuous, but some do have malignant potential. Different lesions with similar clinical presentations make it difficult to arrive at a correct final diagnosis.

Peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) is a reactive, inflammatory, hyperplastic soft tissue growth believed to arise from the gingiva, periosteum, and the periodontal membrane. It comprises about 9% of all gingival growths and is usually seen on the interdental papilla. Lesions are usually small, located in the anterior maxilla and occur more commonly in the second decade with a female predilection. It may be pedunculated or broad based, usually with a smooth surface and varies from pale pink to cherry red in color. It has also been reported that it represents a maturation of a pre-existing pyogenic granuloma or a peripheral giant cell granuloma.[1]

We present an unusual case of a large POF in a 68-year-old woman in the posterior palate.

Case Presentation

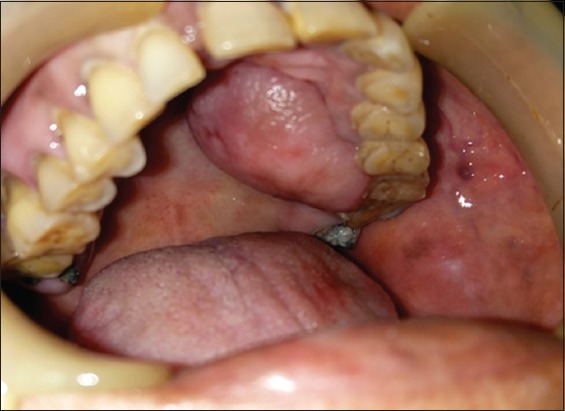

A 68-year-old female presented to our outpatient department with the chief complaint of soft tissue growth on her left palate. History revealed that the growth had appeared 4 months prior as a small nodule and had gradually increased to its present size. Her medical and personal histories were insignificant. Clinical intraoral examination revealed a shiny, oval pink swelling on the left side of palate in relation to the cementoenamel junction of 26. It extended from 23 to 27 anteroposteriorly and was 1 cm lateral to palatal midline to the occlusal surface of the left maxillary molars buccolingually. The growth was smooth, firm to rubbery in consistency, non-fluctuant, pedunculated, non-tender, with no temperature change over the growth, and not associated with discharge [Figure 1]. The lesion was about 3.5 cm mesiodistally and 2.5 cm buccopalatally and did not interfere with occlusion. Grossly, it appeared as an exophytic mass on the hard palate that had apparently originated outside of bone. 26 was Grade I mobile and 28 was carious, but non-tender on percussion.

Figure 1.

Pre-operative palatal lesion

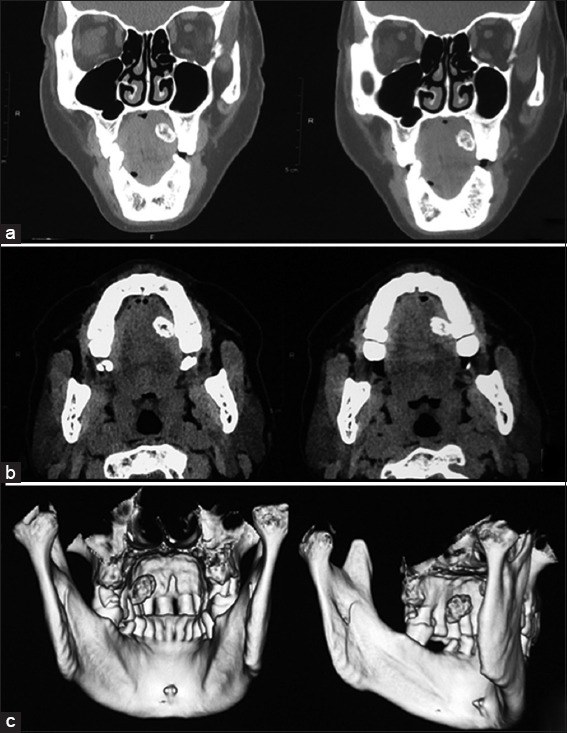

The patient was subjected to radiographic examination and her computed tomography (CT) scans revealed a well-defined radiopaque lesion about 3 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm on the left side of the palate which was attached to the underlying palatal tissue in region of 26, with a distinct plane of cleavage [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Pre-operative computed tomography scan (a): Sagittal, (b): Axial, (c): Three-dimensional reconstruction) images revealing a well-defined radiopaque palatal lesion on the left side with an evident plane of cleavage

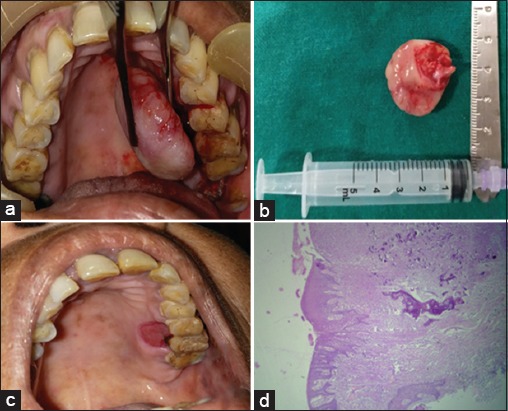

After routine blood examinations, excisional biopsy of the lesion was done under antibiotic coverage and local anesthesia after obtaining written informed consent. The lesion was isolated and dissected from its stalk on the palatal mucosa of 26 and removed in toto [Figure 3a]. The excised specimen measured about 4 cm × 4 cm × 2 cm with glistening smooth pink surfaces all around, except the resected base of the lesion which was severed and red [Figure 3b]. The surgical site on the palate was allowed to heal by secondary intention [Figure 3c] and a surgical splint was provided, to facilitate this. Extraction of 28 was done with thorough curettage of the adjacent periodontal ligament (PDL) and periosteum to prevent recurrence. Histological examination revealed epithelium overlying a richly cellular fibroblastic connective tissue stroma comprising bony trabeculae with osteoblastic rimming of mature bone with a predominantly lamellar structure [Figure 3d], confirming the lesion as POF. On regular follow-up, the lesion healed uneventfully with no complications.

Figure 3.

(a) Intraoperative photograph, (b) Excised specimen, (c) Post-operative site of lesion, (d) Photomicrograph of lesion showing epithelium overlying connective tissue stroma comprising of bony trabeculae with osteoblastic rimming (×4)

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to present an unusual case of a large POF on the posterior palate in an elderly female.

The term, “POF” was coined for a lesion that is reactive in nature, and it is not the extraosseous counterpart of a central ossifying fibroma (OF) of the maxilla and mandible.[1] POF can be described by various synonyms such as peripheral fibroma with osteogenesis, peripheral fibroma with calcification, fibrous epulis, calcifying fibroblastic granuloma, peripheral cemento-OF, and peripheral odontogenic fibroma (PODF).[1] It can be triggered by irritants such as restorations, dental appliances, plaque, and calculus, as in our patient. The location of the posterior palate and in relation to the molars is rare and almost 60% of the lesions occur in the maxilla and anterior gingiva.[2] Large lesions are sparsely encountered (usually smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter) and can lead to diastema formation, resorption of the crestal bone, and cosmetic deformity.[3]

Although the etiopathogenesis of POF is uncertain, an origin from cells of PDL has been suggested. The reasons for considering PDL origin for POF include exclusive occurrence of POF in the gingival (PDL), the proximity of gingiva to the PDL, and the presence of oxytalan fibers within the mineralized matrix of some lesions. Excessive proliferation of mature fibrous connective tissue is a response to gingival injury/irritation, subgingival sulcus, or a foreign body in the gingival sulcus. Chronic irritation of the periosteal and periodontal membrane causes connective tissue metaplasia with bone formation and dystrophic calcification. POF can also be due to genetic mutations that predispose to gingival soft tissue overgrowths that contain mineralized product or ossification.[4]

POF can exhibit either ulcerated or smooth surfaces. The non-ulcerated lesions are histologically identical to the ulcerated ones except for the presence of an intact surface epithelium. Ulcerated lesions are generally associated with pain and typically comprise three zones – the superficial ulcerated layer covered with a fibrinous exudate and enmeshed with polymorphonuclear neutrophils and debris, the middle layer composed exclusively of proliferating fibroblasts with diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, and the innermost collagenized connective tissue layer with less vascularity and high cellularity.[2] Osteogenesis consisting of osteoid and bone formation is a prominent feature, which can even occasionally reach the surface. The calcified material can be mature lamellated trabecular bone, immature highly cellular bone, or circumscribed amorphous with acellular/minute microscopic granular foci of calcification.[1] Cementum-like material is scarcely found and dystrophic calcifications are more common in ulcerated lesions.[2]

Differential diagnosis of POF mainly includes PODF and OF. POF is more common in females and in the anterior maxilla in contrast to the male and the posterior mandibular predilection of PODF.[3] The characteristic oxytalan fibers within its calcified structures, which can arise from outside the PDL as well are not seen in PODF. OF exhibits similar histopathologic characteristics and shares PDL origin with POF, but both have different proliferative activities. POF is a reactive lesion, whereas OF is a benign neoplastic lesion, a type of fibro-osseous lesion.[5] An infrequently used term periosteal ossifying fibroma was also coined to describe lesions with true neoplastic growths arising from the palatal periosteum, to differentiate those from POF.

Gingival lesions that clinically imitate POF are peripheral giant cell granuloma, fibroma, pyogenic granuloma, calcifying epithelial odontogenic cyst, calcifying odontogenic cyst, and other few other odontogenic and non-odontogenic cysts,[6] but POF can be differentiated radiographically from these by the presence of a distinct radiopaque foci within the soft tissue tumor mass and absence of a cystic consistency both clinically and intraoperatively.[7]

Other lesions that occur on the palate and can obscure diagnosis include periapical abscess, which is typically associated with a non-vital tooth or a localized periodontal defect and lymphomas (non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas), which although are common on the palate are diffuse lesions unlike well-differentiated POFs.[8] Salivary gland tumors can also be distinguished on the basis of presentation and histopathology.[9] Carcinoma of the maxillary sinus can remain asymptomatic for long periods and is associated with elderly patients, but no abnormality is detected on the coronal section of CT, except polypoid mucosal thickening of the maxillary sinus and nasal septum deviation.[10] Palatal tissues contain components of soft tissue and so soft tissue tumors such as lipoma, fibroma, neurofibroma, and neurilemmoma should also be considered in the differential diagnoses. Thorough clinical examination and radiographs can rule out these lesions.[7]

In children, POFs can exhibit an exuberant growth rate and reach a significant size in a relatively short span of time. It is difficult to clinically differentiate between most reactive gingival lesions, particularly in the initial stages. Early recognition and definitive surgical intervention results in fewer associated complications such as erosion of bone, tooth displacement, or delayed tooth eruption. POFs may also pose a hindrance for denture placement and difficulty in mastication or act as a speech impediment in adult patients.

Treatment requires proper surgical intervention that ensures deep excision of the lesion including periosteum and affected PDL. As they occur due to continuous trauma and irritation, thorough root scaling of adjacent teeth and/or elimination of etiology should be accomplished. The recurrence rate varies from 7% to 20%[4] and can be contributed to incomplete removal of the irritant.

It is suggested that there is no absolute histological distinction between bone and cementum. As the so-called cementum-like globules of calcification are seen in fibro-osseous lesions in all membranous bones, it is unrealistic to separate the ossifying and cementifying lesions and it is speculated that the fibro-osseous lesions might represent stages in the evolution of a single disease process passing through the stages of fibrous dysplasia to OF to cementoid lesions.[1]

Due to similar clinical presentation of reactive soft tissue overgrowths, POFs present a diagnostic dilemma for the dentists. Palatally originating POFs are very rare and the case presented is of an elderly female in the seventh decade with a unique site of presentation (posterior palate) as compared to the younger and anterior, labial gingival predisposition. The clinical presentation was very unusual – a large, non-ulcerated, smooth lesion with a shiny surface with a unique radiographic presentation not described before.

Conclusion

Many cases of POF can progress and persist for years before the patient seeks treatment as it is asymptomatic and has a slow and limited growth potential, as in our case. Its rare clinical and radiographic presentation should be considered and various differentials should be excluded before treatment is initiated. Our knowledge of the origin of POF is still vague and although PDL source is considered, recent reports indicate a genetic predisposition. Further studies are needed to provide insight into the etiopathogenesis of this lesion and thereby its prevention. Surgical excision is the only treatment modality and close post-operative follow-up is mandatory due to the high recurrence rates.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.John RR, Kandasamy S, Achuthan N. Unusually large-sized peripheral ossifying fibroma. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2016;6:300–3. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.200347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:452–61. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poon CK, Kwan PC, Chao SY. Giant peripheral ossifying fibroma of the maxilla:Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:695–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar SK, Ram S, Jorgensen MG, Shuler CF, Sedghizadeh PP. Multicentric peripheral ossifying fibroma. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:239–43. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesquita RA, Orsini SC, Sousa M, de Araújo NS. Proliferative activity in peripheral ossifying fibroma and ossifying fibroma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:64–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuisia ZE, Brannon RB. Peripheral ossifying fibroma-a clinical evaluation of 134 pediatric cases. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:245–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhanuthai K, Sappayatosok K, Kongin K. Pleomorphic adenoma of the palate in a child:A case report. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E73–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manveen JK, Subramanyam RV, Harshminder G, Madhu S, Narula R. Primary B-cell MALT lymphoma of the palate:A case report and distinction from benign lymphoid hyperplasia seudolymphoma) J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:97–102. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.92982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chundru NS, Amudala R, Thankappan P, Nagaraju D. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of palate:A case report and review of literature. Dent Res J. 2013;10:274–8. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.113372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terada T. Primary small cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus:A case report with immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study involving KIT and PDGFRA. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:264–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]