Abstract

Background and aims:

Among adolescents, risk preference and deviant behaviors are associated with marijuana use, which exhibit substantial historical trends. We examined 1) trends, 2) effect modification by sex and age, 3) associations of marijuana use with deviant behaviors and risk preferences, and 4) differences by sex, age, and year.

Design:

Adjusted logistic and relative risk regression models, using data from the 2002–2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, annual cross-sectional surveys of U.S. households.

Setting:

U.S.

Participants:

A nationally representative sample of adolescents 12–17 years-old (n=230,452).

Measurements:

We estimated associations between past-year marijuana use (self-reported using CAPI/ACASI), deviant behavior (i.e., selling drugs; stealing; attacking someone), and risk preference (i.e., getting a kick; testing oneself).

Findings:

Marijuana use, deviant behaviors, and risk preferences declined among adolescents from 2002–2014. There were no significant sex or age differences in the decline of marijuana use over time. There were sex (sold drugs: β=0.90, 95% CI: 0.75, 1.04) and age (attacked someone: β=0.32, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.42) differences in the prevalence of deviant behaviors, and trends over time differed by sex and age for attacking someone.

Conclusions:

While marijuana use, deviant behavior, and risk preferences among U.S. adolescents declined from 2002 to 2014, associations have remained stable, with marijuana use positively associated with deviant behaviors and risk preferences.

Keywords: deviance, risk preference, marijuana, adolescents, trends, gender differences, substance use

INTRODUCTION

In 2016, 12% of adolescents 12–17 years-old reported past-year marijuana use (1). From 2002–2014, trends in marijuana and other substance use declined among this age group in the U.S. (2) and other countries (3–5), indicating evidence of global shifts. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have indicated that heavy and chronic marijuana use during adolescence is associated with adverse consequences later in life, including neurocognitive problems, low academic achievement, and unhealthy relationships (6–9). Given these consequences, it is important to track changes in trends in marijuana use among adolescents, especially given the changes in state-based marijuana legalization in the U.S. To date, adolescent marijuana use has remained unchanged after the enactment of medical marijuana laws according to cross-sectional studies (10–14), but prevalence of marijuana use might increase with the recent enactment of recreational marijuna laws.

Two factors consistently associated with marijuana use in adolescence are risk preference and deviant behavior. Risk preference, which is the need for varied, novel and complex sensations and experiences (15), is understood to be a biologically-driven, normative trait (16). While variable across individuals, in aggregate it is heightened during adolescence and usually begins to wane into adulthood (16). Adolescents who have a high preference for risk are more likely to engage in deviant and norm-violating behaviors (e.g., crime and substance use), which can lead to unintentional and preventable morbidity and mortality (16–18). Deviant behaviors are associated with negative outcomes later in life (19,20), crime and violence-related behaviors, engagement in risky behaviors, social disruption, and marijuana and other illicit drug use (19,21).

Longitudinal studies indicate that deviant behaviors and risk preference are associated with increased marijuana use among adolescents (22,23). Adolescents who engage in deviant behaviors are more likely to use marijuana when they associate with deviant and antisocial peers who use and have access to illicit drugs, have poor parental supervision/support, and are exposed to physical abuse and violence (24–26). Additionally, risk preference during adolescence is associated with peer deviance, and positive feelings and beliefs about peers who use marijuana (23).

While risk preference and deviant behaviors are associated with an increased risk of marijuana use during adolescence, much remains to be understood about these associations, specifically whether these trends and associations are increasing or decreasing over time, and the magnitude of these effects by sex and age. Boys are more likely to self-report and engage in risky behaviors compared with girls, but these differences are dependent on the age of the adolescent and contextual factors (18). Additionally, adolescent boys are more likely to engage in violence-related deviant behaviors (i.e., fighting and carrying a weapon) and to report more alcohol and drug use behaviors (18) compared with girls.

Yet available evidence suggests that the magnitude of the association of marijuana use with risk preference and deviant behaviors may be changing over time and across demographic subgroups (e.g., age and sex difference). Crime and adolescent reports of criminal activity have been declining in the U.S. for the past decade, more so among boys than girls, whereas marijuana use has not (27). The decline in adolescent criminal activity coincides with declines in tobacco, alcohol, and prescription drug misuse (28), as well as activities associated with the transition to adulthood such as (e.g., working for pay) (29). Different mechanisms may underlie the trends in deviance and marijuana use, which would suggest that the two are increasingly de-coupled. Understanding age, sex, and yearly differences in the trends and associations of marijuana use with deviant behavior and risk preference allows for policymakers to determine which subset of adolescents who use marijuana are at-risk or high risk for use and require focused initiatives.

We examined 1) historical trends in marijuana use, deviant behavior, and risk preference from 2002–2014 among adolescents in the U.S., 2) effect modification of these trends by sex and age, 3) the association of marijuana use with deviant behaviors and risk preferences, and 4) differences in these associations by sex, age, and year. We used nationally representative epidemiological cross-sectional data previously used to examine historical trends in substance use (30,31) that provides a unique opportunity to examine trends, associations, and sex differences in marijuana use, deviant behaviors, and risk preference among adolescents.

METHODS

Data were drawn from the 2002–2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) public use files. Sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA), NSDUH is an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional series of studies which collects data on the prevalence of substance use and abuse, mental health measures, and other behaviors among non-institutionalized individuals ages 12 and older. NSDUH collects data on more than 17,500 youth (ages 12–17), 17,500 young adults (ages 18–25) and 18,800 adults ages 26+ using an independent multistage area probability sample for the District of Columbia and each of the 50 states (32). Adolescents and young adults were oversampled to obtain reliable estimates among these populations. Computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) were used to administer survey items to ensure respondent confidentiality and increase honest reporting of sensitive data (32,33).

Parental/guardian consent and adolescent consent were obtained for all adolescents included in the series. For 2002–2014, the survey weighted interview response rate among adolescents ranged from 80% to 90%. NSDUH/SAMHSA provided analytic sampling weights. Additional information on NSDUH, such as Institutional Review Board approval through RTI International, can be found elsewhere (32,33).

This study restricted the data analyses to adolescents (12–17 year-olds) sampled from 2002–2014 (N=230,452). Fifty-one percent of the adolescents included in this analysis were male, 63.3% were Non-Hispanic White, 15.9% Non-Hispanic Black, and 20.8% Hispanic. Approximately half of the adolescents were in junior high and 45% were in high school; 31.9% had a total family income of $20,000-$49,999 and 32.8% of ≥$75,000.

Measures

Past-year deviant behaviors

Three items assessing deviant behaviors were included: “During the past 12 months, how many times have you… “sold illegal drugs?”, “stolen or tried to steal anything worth more than $50?”, and “attacked someone with the intent to seriously hurt them?” Responses for each question were based on a five-point scale (0=0 times, 1=1 or 2 times, etc.). Responses to each question were recoded as a dichotomous variable (0=0 times/none, 1=1+ times) because of sparse data and potential underreporting. The reliability of these dichotomized items have been demonstrated as moderate-to-substantial among 12–17 year-olds: sold illegal drugs (Cohen’s kappa ([k]=0.53), stole (k=0.65), and attacked someone (k=0.63) (34).

Risk preference

Two items assessing risk preferences were included: “How often do you get a real kick out of doing things that are a little dangerous?” (i.e., “getting a kick”) and “How often do you like to test yourself by doing something a little risky?” (i.e., “testing oneself”). Respondents reported frequency responses on a four-point scale (1=never, 2=seldom, 3=sometimes, 4=always). These two items were recoded as dichotomous variables to differentiate endorsing no risk preference (0=never) and any risk preference (1=seldom, sometimes, or always) because of sparse data at the upper end of the distribution and potential underreporting.

Past-year marijuana use

Marijuana use in the past-year was included from the imputation revised recency of marijuana use question in the NSDUH (32). Responses were coded as dichotomous (0=did not use marijuana in the past-year, 1=any marijuana use in the past-year). Past-year marijuana use has been shown to be reliable among persons ≥12 years-old: (k=0.82; 34).

Covariates

We included the following covariates: age (12–14 vs. 15–17 year-olds), sex, race/ethnicity (i.e., Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic Native American, Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian, Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic >1 race, and Hispanic), total family income (<$20,000, $20,000-$49,999, $50,000-$74,999, ≥$75,000), and study year (2002–2014).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using Stata SE 14.2 statistical software (30). Survey-provided sampling weights were divided by the number of survey years and used to derive nationally-representative estimates accounting for the NSUDH complex survey design.

Univariate analyses were used to calculate participant socio-demographics. To examine the prevalence of deviant behaviors, risk preferences, and marijuana use by sex, age, and study year, we calculated weighted proportions using survey-provided sampling-weights, which were then plotted.

Separate adjusted logistic regression models were used to examine trends in the log-odds of (1) marijuana use and (2) deviant behaviors (selling drugs, stealing, attacking) by estimating the association between these variables and study year (2002–2014). Separate adjusted relative risk regression models were used to examine trends in the log of risk preference (getting a kick and testing oneself) by estimating the association between these variables and study year. Effect modification was assessed by including statistical interaction terms between (1) sex and year and (2) age and year in the fully adjusted logistic and relative risk regression models. Study year was included in all models as a continuous variable. Next, we assessed the associations between marijuana use (as the outcome) and separate models with each of the three deviant behavior and two risk preference items as exposures, including effect modification by sex, age, and year.

All logistic and relative risk regression models were adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and family income. A piecewise linear spline function (knot=2007) was used in all logistic regression models that included marijuana use as an outcome to account for the non-linear trend of marijuana use over time (35,36). The svylogitgof command in Stata was used to determine that the models including the piecewise linear spline fit the data better than models excluding it.

Alpha of 0.05 using two-sided tests was established for statistical significance.

Missing Data

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the best method for coding missing data, including data coded as “refused” and “I don’t know”. Missing data for past-year deviant behaviors: sold drugs (n=718), stole (n=781), and attacked someone (n=796). Missing data for risk preference: getting a kick (n=3,372) and testing oneself (n=1,773). Following sensitivity analyses, all missing data for past-year deviant behaviors was coded as “0=0 times” and all missing data for risk preference was coded as “0=never”.

RESULTS

Trends in marijuana use, deviant behavior, and risk preference over time and by sex and age

Marijuana use

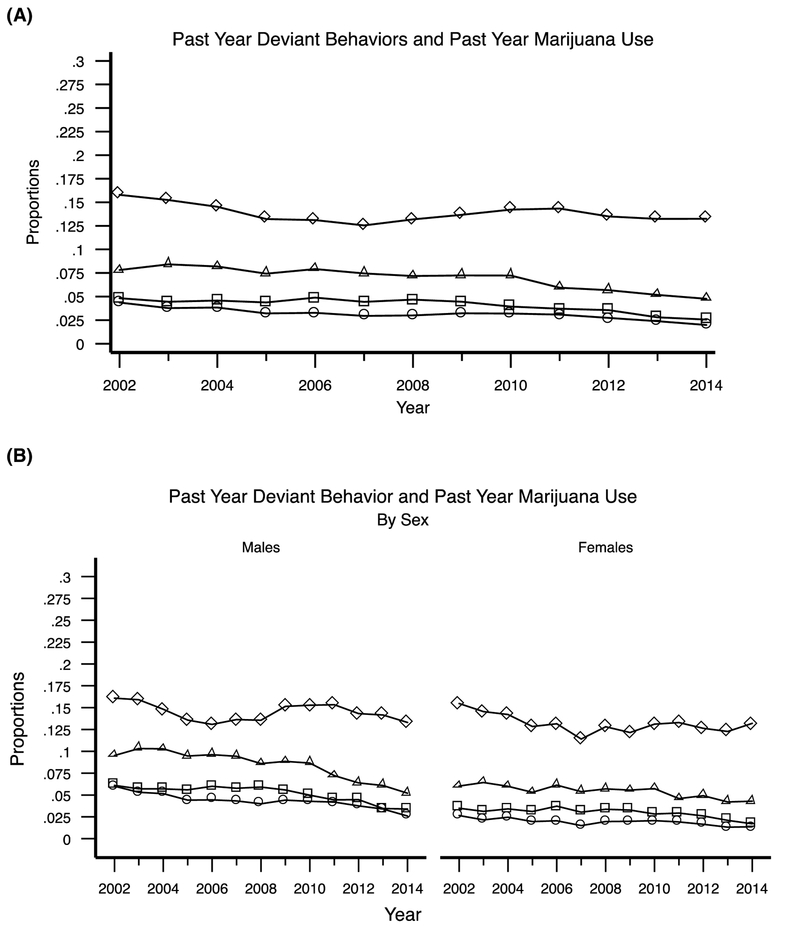

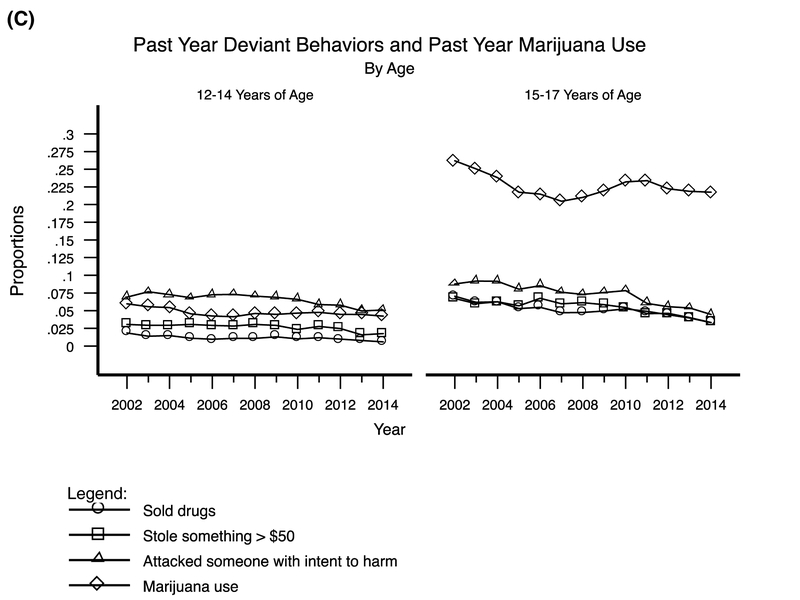

Any past-year marijuana use decreased from 15.8% in 2002 to 13.3% in 2014 (Figure 1A). The log-odds of marijuana use decreased between 2002 and 2007 (β=−0.05, 95% CI: −0.06, −0.04), and increased between 2007 to 2014 (spline-β=0.01, 95% CI: 0.006, 0.02).

Figure 1.

Weighted proportion estimates of (A) past-year deviant behavior and past-year marijuana use among US adolescents from NSDUH 2002–2014, (B) stratified by sex, and (C) stratified by age.

In the fully adjusted model, there was no significant difference in log odds of marijuana use by sex (β=−0.005, 95% CI: −0.13, 0.12), but it was higher among older adolescents compared with younger adolescents (β=1.70, 95% CI: 1.55, 1.84). After accounting for sex and age differences, log odds of marijuana use decreased between 2002–2007 and remained stable after 2007; these time trends did not differ by sex or age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adjusted logistic regression models of marijuana use among adolescents from 2002–2014

| Log odds of marijuana use | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1.1 | Model 1.2 | |

| Variables | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) |

| Year (2002 to 2007) | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.07 (−0.10, −0.05)*** |

| Male | 0.12 (0.09, 0.16)*** | −0.005 (−0.13, 0.12) |

| Male x year | - | 0.02 (−0.002, 0.05) |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.79 (1.75, 1.82)*** | 1.70 (1.55, 1.84)*** |

| Age x year | - | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) |

| Spline (2007 to 2014) | 0.01 (0.006, 0.02)*** | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) |

| Male x spline | - | −0.02 (−0.06, 0.01) |

| Age x spline | - | −0.007 (−0.05, 0.04) |

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

Note: All models were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity and family income. A linear spline was used for the association between year and marijuana use with a knot at 2007

Deviant behavior

The prevalence of all deviant behaviors significantly declined from 2002–2014 (Table 2 and Figure 1A). Selling drugs: 4.4% to 2.0% (β=−0.05, 95% CI: −0.06, −0.04); stealing: 4.8% to 2.6% (β=−0.04, 95% CI: −0.05, −0.04); and attacking someone: 7.8% to 4.8% (β=−0.04, 95% CI: −0.05, −0.04).

Table 2.

Adjusted logistic regression models of deviant behavior among adolescents in the 2002–2014 NSDUH

| Log odds of selling drugs | |||

| Model 2.1a | Model 2.2a | ||

| Variables | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Year | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.08, −0.03)*** | |

| Male | 0.86 (0.79, 0.92)*** | 0.90 (0.75, 1.04)*** | |

| Male x year | - | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.57 (1.49, 1.64)*** | 1.48 (1.29, 1.67)*** | |

| Age x year | - | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | |

| Log odds of stealing something >$50 | |||

| Model 2.1b | Model 2.2b | ||

| Variables | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Year | −0.04 (−0.05, −0.04)*** | −0.04 (−0.05, −0.02)*** | |

| Male | 0.58 (0.53, 0.64)*** | 0.60 (0.47, 0.73)*** | |

| Male x year | - | −0.002 (−0.02, 0.01) | |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 0.77 (0.71, 0.84)*** | 0.83 (0.68, 0.97)*** | |

| Age x year | - | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | |

| Log odds of attacking someone with the intent to harm | |||

| Model 2.1c | Model 2.2c | ||

| Variables | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Year | −0.04 (−0.05, −0.04)*** | −0.01 (−0.03, −0.003)* | |

| Male | 0.49 (0.45, 0.54)*** | 0.66 (0.56, 0.76)*** | |

| Male x year | - | −0.02 (−0.03, −0.01)*** | |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.18)*** | 0.32 (0.22, 0.42)*** | |

| Age x year | - | −0.03 (−0.04, −0.01)*** | |

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

Note: All models were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity and family income.

Legend:

Sex (Figure 1B) and age (Figure 1C) differences in the prevalence of deviant behaviors were observed, with deviant behaviors being significantly higher among boys than girls, and higher among 15–17 year-olds than 12–14 year-olds. While trends over time indicate decreases in all behaviors, there was a greater reduction in the log-odds of self-reporting attacking someone from 2002–2014 among boys compared with girls (interaction-β=−0.02; 95% CI: −0.03, −0.01), and among 15–17 year-olds compared with 12–14 year-olds (interaction-β=−0.03; 95% CI: −0.04, −0.01). Beta estimates for interaction can be interpreted as the change in the association between sex and age with deviant behavior given a one year increase in time.

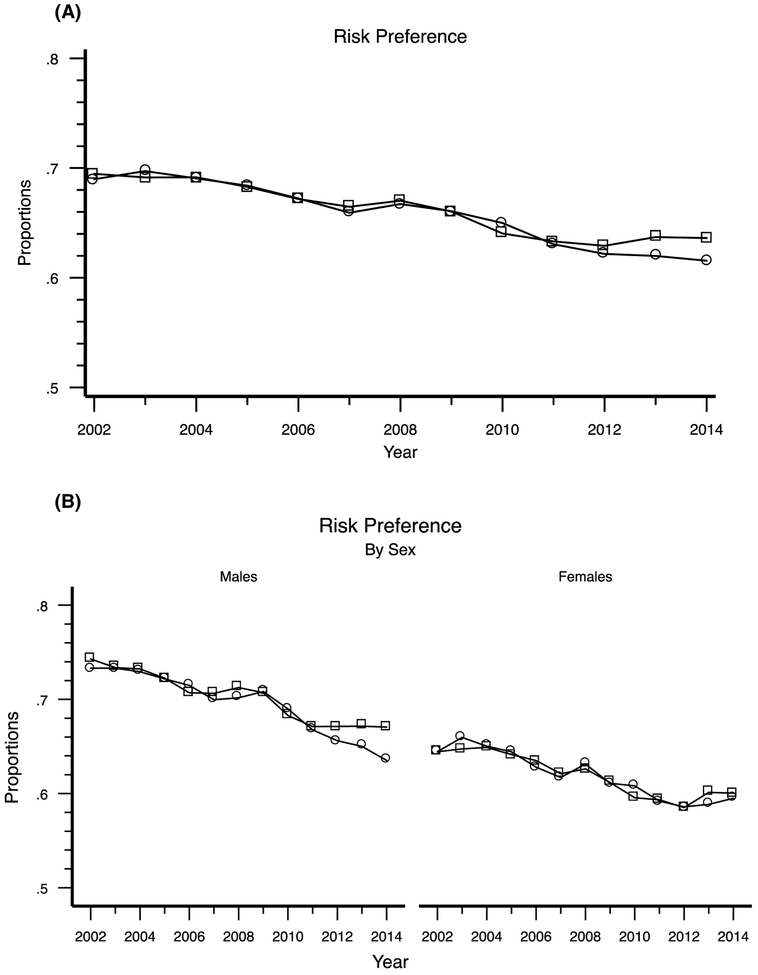

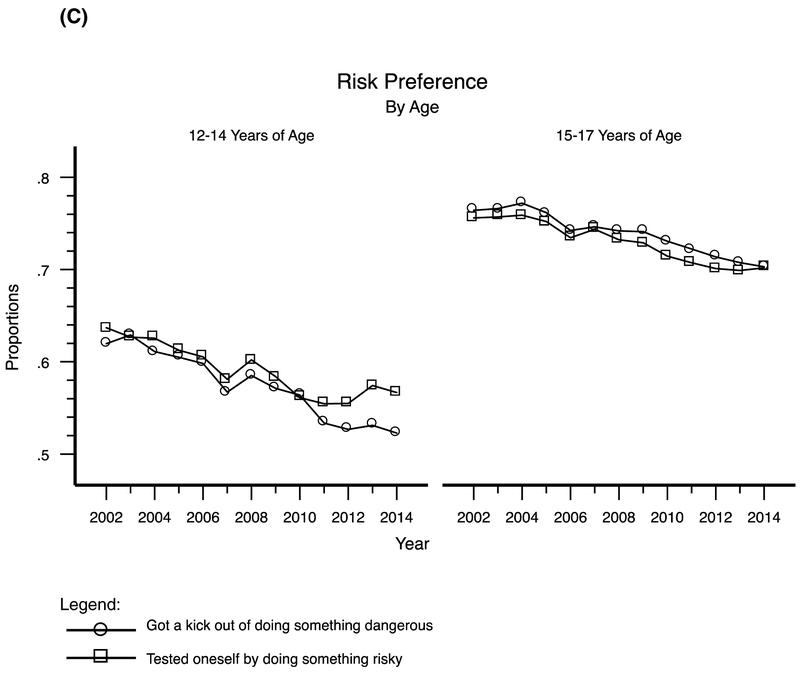

Risk preference

The prevalence of risk preference traits declined from 2002–2014 among adolescents (Table 3 and Figure 2A). Getting a kick decreased from 69.0% to 61.6% (β=−0.01, 95% CI: −0.01, −0.009) as did testing oneself, from 69.5% to 63.6% (β=−0.01, 95% CI: −0.009, −0.008).

Table 3.

Adjusted relative risk regression models of risk preference among adolescents from 2002–2014

| Log of getting a kick out of doing something dangerous | |||

| Model 3.1a | Model 3.2a | ||

| Variables | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Year | −0.01 (−0.01, −0.009)*** | −0.02 (−0.02, −0.01)*** | |

| Male | 0.11 (0.09, 0.11)*** | 0.11 (0.10, 0.13)*** | |

| Male x year | - | -0.0005 (−0.002, 0.001) | |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 0.24 (0.23, 0.24)*** | 0.17 (0.15, 0.18)*** | |

| Age x year | - | 0.01 (0.007, 0.01)*** | |

| Log of testing oneself by doing something risky | |||

| Model 3.1b | Model 3.2b | ||

| Variables | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Year | −0.01 (−0.009, −0.008)** | −0.01 (−0.02, −0.01)*** | |

| Male | 0.12 (0.11, 0.13)*** | 0.12 (0.10, 0.13)*** | |

| Male x year | - | −0.0004 (−0.002, 0.002) | |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 0.20 (0.19, 0.21)*** | 0.16 (0.15, 0.18)*** | |

| Age x year | - | 0.005 (0.003, 0.01)*** | |

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

Note: All models were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity and family income.

Figure 2.

Weighted proportion estimates of (A) risk preference traits among US adolescents from NSDUH 2002–2014, (B) stratified by sex, and (C) by age.

Prevalence of getting a kick (β=0.11, 95% CI: 0.10, 0.13) and testing oneself (β=0.12, 95% CI: 0.10, 0.13) was higher among boys compared with girls (Figure 2B). Time trends differed by age (getting a kick: [interaction-β=0.01, 95% CI: 0.007, 0.01]; testing oneself: [interaction-β=0.005, 95% CI: 0.003, 0.01]), indicating that there was a greater increase in risk preferences among older compared with younger adolescents from 2002–2014 (Figure 2C). There were no significant sex differences in time trends of risk preference.

Associations between marijuana use, and deviant behavior and risk preference and differences by sex, age, and study year (Table 4 and 5)

Table 4.

Separate adjusted logistic regression models of the association between marijuana use (outcome) and deviant behavior (exposure) items among adolescents from 2002–2014

| Log odds of marijuana use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Past Year Deviant Behavior | Model 4.1a | Model 4.2a | Model 4.3a |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Selling drugs | 3.40 (3.31, 3.50)*** | 4.13 (3.95, 4.31)*** | 3.16 (2.85, 3.48)*** |

| Year (2002 to 2007) | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** |

| Spline (2007 to 2014) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** |

| Male | −0.02 (−0.06, 0.01) | −0.007 (−0.05, 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.06, 0.01) |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.71 (1.67, 1.75)*** | 1.75 (1.71, 1.79)*** | 1.71 (1.67, 1.75)*** |

| Selling drugs x male | - | −0.43 (−0.59, −0.28)*** | - |

| Selling drugs x age | - | −0.60 (−0.79, −0.40)*** | - |

| Selling drugs x year | - | - | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.10) |

| Selling drugs x spline | - | - | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) |

| Mobel 4.1b | Mobel 4.2b | Mobel 4.3b | |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Stealing something >$50 | 1.89 (1.82, 1.97)*** | 2.60 (2.44, 2.75)*** | 1.74 (1.49, 1.98)*** |

| Year (2002 to 2007) | −0.06 (−0.07, −0.05)*** | −0.06 (−0.07, −0.05)*** | −0.06 (−0.07, −0.05)*** |

| Spline (2007 to 2014) | 0.02 (0.02, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.02, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.02, 0.03)*** |

| Male | 0.06 (0.02, 0.10)** | 0.09 (0.05, 0.13)*** | 0.06 (0.02, 0.10)** |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.76 (1.72, 1.80)*** | 1.83 (1.79, 1.87)*** | 1.76 (1.72, 1.80)*** |

| Stealing x male | - | −0.36 (−0.48, −0.25)*** | - |

| Stealing x age | - | −0.64 (−0.77, −0.52)*** | - |

| Stealing x year | - | - | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) |

| Stealing x spline | - | - | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) |

| Modell 4.1c | Model 4.2c | Model 4.3c | |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Attacking someone with the intent to harm | 1.26 (1.21, 1.31)*** | 1.67 (1.55, 1.79)*** | 1.25 (1.09, 1.41)*** |

| Year (2002 to 2007) | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.07, −0.04)*** |

| Spline (2007 to 2014) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.02, 0.03)*** |

| Male | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11)*** | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14)*** | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11)*** |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.81 (1.77, 1.84)*** | 1.86 (1.82, 1.90)*** | 1.81 (1.77, 1.84)*** |

| Attacking someone x male | - | −0.27 (−0.37, −0.16)*** | - |

| Attacking someone x age | - | −0.35 (−0.46, −0.24)*** | - |

| Attacking someone x year | - | - | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) |

| Attacking someone x spline | - | - | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.02) |

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

Note: All models were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity and family income. A linear spline was used for the association between year and marijuana use with a knot at 2007

Table 5.

Separate adjusted logistic regression models of the association between marijuana use (outcome) and risk preference (exposure) items among adolescents from 2002–2014

| Risk Preference | Log odds of marijuana use | ||

| Model 5.1a | Model 5.2a | Model 5.3a | |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Getting a kick out of doing something dangerous | 1.44 (1.39, 1.50)*** | 1.89 (177, 2.01)*** | 1.31 (1.12, 1.50)*** |

| Year (2002 to 2007) | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.08 (−0.11, −0.04)*** |

| Spline (2007 to 2014) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07)*** |

| Male | 0.05 (0.01, 0.08)* | 0.40 (0.31, 0.49)*** | 0.05 (0.01, 0.08)* |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.65 (1.61, 1.69)*** | 1.92 (1.80, 2.04)*** | 1.65 (1.61, 1.69)*** |

| Getting a kick x male | - | −0.41 (−0.50, −0.31)*** | - |

| Getting a kick x age | - | −0.32 (−0.45, −0.19)*** | - |

| Getting a kick x year | - | - | 0.03 (−0.003, 0.07) |

| Getting a kick x spline | - | - | −0.06 (−0.12, −0.01)* |

| Model 5.1b | Model 5.2b | Model 5.3b | |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Testing oneself by doing something risky | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21)*** | 1.69 (1.57, 1.82)*** | 1.14 (0.96, 1.31)*** |

| Year (2002 to 2007) | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.04)*** | −0.06 (−0.09, −0.03)*** |

| Spline (2007 to 2014) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03)*** | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05)*** |

| Male | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09)** | 0.42 (0.34, 0.51)*** | 0.05 (0.01, 0,09)** |

| Age (15–17 year-olds) | 1.69 (1.65, 1.73)*** | 2.03 (1.91, 2.14)*** | 1.69 (1.65, 1.73)*** |

| Testing oneself x male | - | −0.44 (−0.53, −0.35)*** | - |

| Testing oneself x age | - | −0.40 (−0.52, −0.28)*** | - |

| Testing oneself x year | - | - | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.04) |

| Testing oneself x spline | - | - | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) |

p≤0.05;

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

Note: All models were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity and family income. A linear spline was used for the association between year and marijuana use with a knot at 2007

Deviant behavior

Past-year marijuana use was positively associated with selling drugs, stealing, and attacking someone (Table 4). Significant differences in these associations by sex and age indicate that there is a smaller magnitude of association between marijuana use and deviant behaviors among boys compared with girls, and among 15–17 year-olds compared with 12–14 year-olds. We did not find a significant difference in the association between marijuana use and selling drugs, stealing, or attacking someone by study year (2002–2014). This indicates that the magnitude of the association between marijuana use and deviant behaviors has not significantly changed over time.

Risk preference

Past-year marijuana use was positively associated with getting a kick, and testing oneself (Table 5). Significant differences in these associations by age and sex suggest that the magnitude of the association between marijuana use and risk preference is smaller among boys than girls, and among 15–17 year-olds compared with 12–14 year-olds. We did not find a significant difference in the association between marijuana use and getting a kick and testing oneself by study year (2002–2014), suggesting that the magnitude of the association between marijuana use and risk preference has not significantly changed over time.

DISCUSSION

This study examined trends and associations in marijuana use, deviant behaviors, and risk preference over time among adolescents, and assessed differences in these factors by sex and age across 13 years of nationally representative data in the U.S. While other studies have assessed trends and associations in deviant behavior, risk preference, and marijuana use over time, this is the first study to assess the differences by sex and age over time (2002–2014). Three key findings emerged from this analysis. First, the prevalence of marijuana use, deviant behavior, and risk preference all significantly declined over time, including a decline in marijuana use from 2002 to 2007. Second, there were greater reductions in the prevalence of attacking someone and both risk preference traits among boys compared with girls from 2002–2014. Finally, despite prevalence decreases over time, the magnitude of association between variables has not decreased. Indeed, we did not find a difference in the association of marijuana use with risk preference and deviant behavior from 2002–2014.

Our findings are consistent with significant declines in the prevalence of conduct problems among adolescents (37,38), and steady declines in juvenile arrest rates for crime and violence-related offenses since 2000 (39). Engagement in risky behaviors have declined over the years (29). However, preferences for risk, regardless of behavior, have not declined at the same rate among a nationally-representative school sample of high school seniors (mean aged 17–18), and have demonstrated a generally positive slope for girls (40). These differences may arise due to the inclusion of non-school attending youth in a community-based versus school-based sample, as well as the broader range of adolescents at younger ages than senior year. These declines are part of a broader trend towards delayed adult activities (e.g., having sex, driving) among adolescents (29,41), as well as a longer transition to adulthood (42). These delays are often attributed to a greater parental investment (due to older age of childbearing and fewer children) (43,44), general economic prosperity prior to The Great Recession, and a change in how adolescents interact due to technology that allows interaction without unsupervised time alone with other adolescents, which is when deviant activities and experimentation with drug use often occur (45,46). Declines in marijuana use, deviance, and risk preference in youth are also occurring in the context of changing medical marijuana laws, which have not been causally related to changes in marijuana use in youth in a recent meta-analysis (47) or affected perceived availability of marijuana use in ages 12–17 (12). These declines are paralleled by declines in the trends of alcohol and tobacco use among U.S. adolescents 12–17 year of age from 2002–2014 (48).

While there was a higher prevalence of marijuana use, deviant behavior and risk preference among adolescent boys compared with girls, there was also a significantly greater reduction in the trends over time of attacking someone, getting a kick, and testing oneself among boys compared with girls. These finding are supported by other studies showing that boys exhibit more deviant behaviors and engage in more risky behaviors than girls (18,49–51), suggesting that historical declines across sexes may be greater for boys given the higher historical prevalences. Sex differences in deviant behaviors and risk preference may be due to gender role socialization (52), as social norms often dictate normative gendered behaviors. Compared with girls, boys do not have the same punitive consequences for risky and deviant behaviors (53,54). Significant reductions across sex in these factors over time, greater among boys, suggest changes in population-level factors, such as social norms.

Adolescents who self-reported engaging in deviant behaviors had greater log-odds of using marijuana in the past-year, and these associations were smaller in magnitude among boys compared with girls. Similar findings have been documented in the literature, for example, data from Monitoring the Future (1979–2004) indicates that there was a smaller magnitude in the association between deviance proneness and annual marijuana use among 12th grade boys compared with girls (50).

Adolescents who are unsupervised are more likely to engage in deviant and risky behaviors, including using marijuana and other drugs (55–57). Yet, information technology (IT) and the internet have changed the way adolescents communicate, as 92% of adolescent’s self-report using the internet daily without parental supervision (58). The internet limits face-to-face interactions, reducing the opportunity to engage in deviant and risky behaviors. Such interactions may be even more limited among boys, who engage in video game use with peers (without face-to-face contact) more than girls (59–61). The internet may be decreasing traditional face-to-face/in-person deviant behaviors and increasing online deviant behaviors, such as cyberbullying. Traditional forms of violence and aggression, such as threatening, bullying, and hurting others have been associated with cyberbullying perpetration (62). Future studies should assess whether adolescents who were at-risk for or previously engaged in ‘traditionally’ deviant behaviors now engage in cyberbullying.

Limitations

The use of a series of cross-sectional data is an ideal method for examining population-level historical trends over time, but it is a less powerful design for demonstrating causal inference than individual-level longitudinal data. Use of self-report data can increase reporting bias, especially when collecting data on sensitive subjects which could lead to under-reporting marijuana use, deviant behaviors, and risk preferences. However, the NSDUH data collection methodologies included safeguards to allow for privacy and confidentiality of responses to questionnaires. The sampling frame of NSDUH is non-institutionalized U.S.-households, thus incarcerated adolescents are not included. Incarcerated adolescents may be more likely to use marijuana, engage in deviant behaviors, and have greater preferences for risk (63–64), thus these results do not generalize to adolescents not in the sampling frame. In addition, in using dichotomous indicators of any/no behavior, we did not examine whether frequency of behaviors changed over time. Future studies should address these limitations.

Conclusions

In the U.S., adolescent marijuana use, deviant behaviors and risk preferences have declined among all adolescents from 2002–2014. Larger declines were observed over time among boys who attacked someone, got a kick, and tested oneself compared with girls, and among older adolescents who attacked someone and got a kick compared with younger adolescents. These U.S. trends are comparable to trends in other countries (3–5,65), indicating that marijuana use is shifting among adolescents globally. Our findings provide further support that marijuana use is associated with deviant behaviors and risk preference. Furthermore, at the population-level, the magnitude of these associations were smaller among boys and older adolescents compared with girls and younger adolescents. To further understand the mechanisms/pathways contributing to these declines, future studies should assess the impact of social norms on the association of marijuana use with deviant behaviors and risk preferences, differences in the association of marijuana use with traditional and non-traditional (i.e., cyberbullying) deviant behaviors, and the potentially causal relationship between deviant behaviors and risk preference longitudinally. Understanding changes in the social environment of adolescents may provide insight into the shifting population patterns of marijuana use, deviant behavior, and risk preference.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01DA037866 (PI: Martins) and T32DA031099 (PI: Hasin), and the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences grant R25GM062454 (PI: Abraido-Lanza). The data reported herein come from the 2002–14 NSDUH public data files available at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive and the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, which are sponsored by the Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2016. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azofeifa A, Mattson ME, Schauer G, McAfee T, Grant A, Lyerla R. National Estimates of Marijuana Use and Related Indicators — National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65(No. SS-11):1–25. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6511a1.htm. (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6yDa9fBen). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weier M, Chan GCK, Quinn C, Hides L, Hall W. Cannabis use in 14 to 25 years old Australians 1998 to 2013. Brisbane, AU: Centre for Youth Substance Abuse Research; 2016. Available from: https://cysar.health.uq.edu.au/filething/get/1916/Cannabis%20technical%20report.pdf. (Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/6yDcThJ3F). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arsaell A, Kort KG, Thoroddur B. Adolescent alcohol and cannabis use in Iceland 1995–2015. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017. July 28 [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giordano GN, Ohlsson H, Kendler KS, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Age, period and cohort trends in drug abuse hospitalizations within the total Swedish population (1975–2010). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014. January 1;134:355–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choo EK, Benz M, Zaller N, Warren O, Rising KL, McConnell KJ. The impact of state medical marijuana legislation on adolescent marijuana use. J Adolesc Heal. 2014;55(2):160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerda M, Moffitt TE, Meier MH, Harrington H, Houts R, Ramrakha S, et al. Persistent cannabis dependence and alcohol dependence represent risks for midlife economic and social problems: A longitudinal cohort study. Clin Psychol Sci a J Assoc Psychol Sci. 2016. November;4(6):1028–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson NJ, Isen JD, Khoddam R, Irons D, Tuvblad C, Iacono WG, et al. Impact of adolescent marijuana use on intelligence: Results from two longitudinal twin studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016. February 2;113(5):E500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier MH, Caspi A, Danese A, Fisher HL, Houts R, Arseneault L, et al. Associations between adolescent cannabis use and neuropsychological decline: a longitudinal co-twin control study. Addiction. 2018. February;113(2):257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerda M, Sarvet AL, Wall M, Feng T, Keyes KM, Galea S, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent use of marijuana and other substances: Alcohol, cigarettes, prescription drugs, and other illicit drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018. February;183:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson J, Hodgkin D, Harris SK. The design of medical marijuana laws and adolescent use and heavy use of marijuana: Analysis of 45 states from 1991 to 2011. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017. January;170:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins SS, Mauro CM, Santaella-Tenorio J, Kim JH, Cerda M, Keyes KM, et al. State-level medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived availability of marijuana among the general U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016. December;169:26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JK, Johnson RM, Hodgkin D, Jones AA, Matteucci AM, Harris SK. Heterogeneity of state medical marijuana laws and adolescent recent use of alcohol and marijuana: Analysis of 45 states, 1991–2011. Subst Abus. 2017. October;1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams AR, Santaella-Tenorio J, Mauro CM, Levin FR, Martins SS. Loose regulation of medical marijuana programs associated with higher rates of adult marijuana use but not cannabis use disorder. Addiction. 2017. November 17;112(11):1985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuckerman M Sensation Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal. 1st ed. Taylor & Francis Limited; Psychology Revivals; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg L A Dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Dev Psychobiol. 2010. April;52(3):216–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinberg L A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28(1):78–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ [Internet]. 2014. June [cited 2018 March 20];63(4):1–168. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6304a1.htm. (Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/6yDd1rQhx). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shoemaker DJ. Conduct Problems in Youth: Sociological Perspectives In: Murrihy RC and Kidman AD and Ollendick TH, editors. Clinical handbook of assessing and treating conduct problems in youth. 1st edition New York, NY: Springer; 2010. p. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra K, Shim R, Baltrus P, Heiman HJ, Adekeye O, Rust G. Racial/ethnic disparaties in mental health service utilization among youth participating in negative externalizing behaviors. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(2):123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buil JM, van Lier PAC, Brendgen MR, Koot HM, Vitaro F. Developmental pathways linking childhood temperament with antisocial behavior and substance use in adolescence: Explanatory mechanisms in the peer environment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2017. June;112(6):948–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, et al. Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(4):667–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M. Childhood predictors of adolescent marijuana use: Early sensation-seeking, deviant peer affiliation, and social images. Addict Behav. 2008. September;33(9):1140–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piko BF, Kovács E. Do parents and school matter? Protective factors for adolescent substance use. Addict Behav. 2010;35(1):53–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tucker JS, Green HD, Zhou AJ, Miles JN V, Shih RA, D’Amico EJ. Substance use among middle school students: Associations with self-rated and peer-nominated popularity. J Adolesc. 2011;34(3):513–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, Dishion TJ. Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addict Behav. 2012;37(12):1314–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keyes KM, Gary DS, Beardslee J, Prins SJ, O’Malley PM, Rutherford C, et al. Joint effects of age, period, and cohort on conduct problems among American adolescents from 1991 through 2015. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;187(3):548–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Twenge JM, Park H. The Decline in Adult activities among U.S. adolescents, 1976–2016. Child Dev. 2017. September 18 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miech R, Koester S. Trends in US, past-year marijuana use from 1985 to 2009: An age–period–cohort analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):259–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miech R, Bohnert A, Heard K, Boardman J. Increasing use of nonmedical analgesics among younger cohorts in the United States: a birth cohort effect. J Adolesc Heal. 2013;52(1):35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2002 [Internet]. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor]; 2002. Available from: 10.3886/ICPSR03903.v6. (Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/6yDde5gBo). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2014 [Internet]. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor]; 2014. Available from: 10.3886/ICPSR36361.v1. (Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/6yDdsuv9c). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Reliability of Key Measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Office of Applied Studies, Methodology Series M-8, HHS Publication No. SMA 09–4425). Rockville, MD; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauro PM, Carliner H, Brown QL, Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Rahim-Juwel R, Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Martins SS. Age differences in daily and nondaily cannabis use in the United States, 2002–2014. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018. May;79(3):423–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toms JD, Lesperance ML. Piecewise regression: a tool for identifying ecological thresholds. Ecology. 2003. August 1;84(8):2034–41. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hopfer C Declining rates of adolescent marijuana use disorders during the past decade may be due to declining conduct problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016. Jun;55(6):439–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grucza RA, Agrawal A, Krauss MJ, Bongu J, Plunk AD, Cavazos-Rehg PA, et al. Declining prevalence of marijuana use disorders among adolescents in the United States, 2002 to 2013. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(6):487–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kearney MS, Harris BH, Jácome E, Parker L. Ten economic facts about crime and incarceration in the United States. Hamilton Project, Brookings; 2014. May. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keyes KM, Jager J, Hamilton A, O’Malley PM, Miech R, Schulenberg JE. National multi-cohort time trends in adolescent risk preference and the relation with substance use and problem behavior from 1976 to 2011. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinberg L. Adolescence. 11th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClelland M, Geldhof J, Morrison F, Gestsdóttir S, Cameron C, Bowers E, et al. Self-regulation In: Halfon N, Forrest C, M. Lerner R, M. Faustman E, editors. Handbook of Life Course Health Development. New York, NY: Springer; 2018. p. 275–98. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathews TJ, Hamilton B Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014. [Internet]. NCHS data brief, no 232. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. 2016 [cited 2017 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db232.htm. (Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/6yDeG6VHP). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livingston G Family Size Among Mothers [Internet]. Pew Research Center, Social & Demographic Trends; 2015. [cited 2017 Oct 6]. Available from: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/07/family-size-among-mothers/. (Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/6yDeKx3LE). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borawski EA, Ievers-Landis CE, Lovegreen LD, Trapl ES. Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: The role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2003. August 1;33(2):60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:274–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, Greene E, Le A, Boustead AE, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018. February 22 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H-50; ). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Byrnes JP, Miller DC, Schafer WD. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Little M, Weaver SR, King KM, Liu F, Chassin L. Historical change in the link between adolescent deviance proneness and marijuana use, 1979–2004. Prev Sci. 2008. March;9(1):4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shulman EP, Harden KP, Chein JM, Steinberg L. Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of impulse control and sensation-seeking from easly adolescence to early adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levant RF. Research in the psychology of men and masculinity using the gender role strain paradigm as a framework. Am Psychol. 2011;66(8):765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwamoto DK, Cheng A, Lee CS, Takamatsu S, Gordon D. “Man-ing” up and getting drunk: The role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addict Behav. 2011;36(9):906–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwamoto DK, Corbin W, Lejuez C, MacPherson L. College men and alcohol use: Positive alcohol expectancies as a mediator between distinct masculine norms and alcohol use. Psychol Men Masc. 2014. January; 15(1): 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Averett SL, Argys LM, Rees DI. Older siblings and adolescent risky behavior: does parenting play a role? J Popul Econ. 2011;24(3):957–78. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coley RL, Medeiros BL, Schindler HS. Using sibling differences to estimate effects of parenting on adolescent sexual risk behaviors. J Adolesc Heal. 2008;43(2):133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abar CC, Jackson KM, Colby SM, Barnett NP. Parent–child discrepancies in reports of parental monitoring and their relationship to adolescent alcohol-related behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(9):1688–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.See SG. Parental supervision and adolescent risky behaviors. Rev Econ Househ. 2016;14(1):185–206. Available from: 10.1007/s11150-014-9254-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terlecki M, Brown J, Harner-Steciw L, Irvin-Hannum J, Marchetto-Ryan N, Ruhl L, et al. Sex differences and similarities in video game experience, preferences, and self-efficacy: Implications for the gaming industry. Curr Psychol. 2011;30(1):22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamlen KR. Re-examining gender differences in video game play: Time spent and feelings of success. J Educ Comput Res. 2010;43(3):293–308. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, et al. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2010. March;136(2):151–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sari SV, Camadan F. The new face of violence tendency: Cyber bullying perpetrators and their victims. Comput Human Behav. 2016. June;59:317–26. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (NCJ 251149); January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carson EA, Sabol WJ. Prisoners in 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (NCJ 239808) December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Copeland J, Rooke S, Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people: impact on mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013. Jul;26(4):325–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]