Abstract

This study examined maternal–infant synchrony of hair cortisol at 12 months after birth and the intra-individual stability of maternal hair cortisol in the postpartum period. Participants were selected from an ongoing São Paulo birth cohort project, where families are considered to be “high-risk” due to their chronic stress experiences, with the majority living in slums (favelas). Cortisol was collected through 3-cm segments of hair samples, with values representing approximate levels of cortisol from 9 to 12 months for mothers and children and 6 to 12 months for mothers. Maternal and infant cortisol values reflecting chronic stress 9–12 months after birth were highly correlated (r = .61, p < .001); earlier maternal cortisol levels (6–9 months) and child cortisol levels at 9–12 months (r = .51, p < .001) were also correlated. Maternal cortisol values showed stability over time (r = .79, p < .001). These maternal–infant correlations are high compared to the existing literature on hair cortisol in other mother–child dyads, suggesting stronger synchrony under high-risk contexts where families are faced with challenging circumstances.

Keywords: hair cortisol, high-risk, infant, postpartum, stress

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, hair cortisol has been utilized as a biomarker of chronic stress among humans and animals, with emerging data on its use with children (Karlén, Frostell, Theodorsson, Faresjö, & Ludvigsson, 2013) and infants (Yamada et al., 2007). Hair cortisol appears to capture cumulative cortisol output over a longer period of time (months) relative to other cortisol indices, such as those obtained from saliva, urine, or blood. As an integrated measure, hair cortisol may reflect prolonged stress exposures, making it an ideal measure for assessing vulnerable populations such as children in high-risk neighborhoods.

Given the documented positive associations between adversity, often measured by socioeconomic status (SES), psychosocial stress, and hair cortisol (Wosu, Valdimarsdóttir, Shields, Williams, & Williams, 2013), a major question is whether adversity and/or SES in the family have an impact on hair cortisol in both mothers and children. Since SES may reflect chronic stress due to the exposure of adversity that, in turn, leads to an activation of the HPA axis, it is important to consider children’s HPA response within adverse conditions. Such factors have been examined in salivary cortisol across development, which have showed that children with lower SES have higher basal salivary cortisol levels (Clearfield, Carter-Rodriguez, Merali, & Shober, 2014; Lupien, King, Meaney, & McEwen, 2000), and that maternal depression is associated with higher cortisol levels among children (Ashman, Dawson, Panagiotides, Yamada, & Wilkinson, 2002; Brennan et al., 2008; Lupien et al., 2000). A general pattern has emerged suggesting greater cortisol dysregulation as a function of an adverse environment (Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006).

Extant studies on either family adversity or SES, and hair cortisol in children (Karlén et al., 2013; Liu, Snidman, Leonard, Meyer, & Tronick, 2016; Palmer et al., 2013), have showed either no correlations or small negative correlations with neighborhood-level SES and hair cortisol in 4–18-year-old children from the Netherlands (Vliegenthart et al., 2016) or with parent education and hair cortisol among a heterogeneous SES sample of preschool children (Vaghri et al., 2013). Lower family income was associated with higher levels of hair cortisol in 6-year-old children from a large and ethnically diverse sample from the Netherlands (Rippe et al., 2016). While hair cortisol studies on children do not necessarily include direct measures of psychosocial stress (Liu et al., 2016; Ouellette et al., 2015), direct measures of psychosocial stress within the family have been associated with hair cortisol across populations (Palmer et al., 2013). For instance, parenting stress and maternal depression were positively correlated with hair cortisol among 1-year-old Black and White urban children from Tennessee (Palmer et al., 2013). Potential methodological issues that might explain the mixed findings include differences in the developmental periods of assessment and the homogeneity of populations within and across studies. Studies on hair cortisol from adverse environments are scarce as well (Flom, St John, Meyer, & Tarullo, 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Wosu et al., 2013).

Cortisol, when captured by hair, may help to clarify possible physiological synchrony between mothers sand infants. It is hypothesized that dyadic synchrony may be a “salient physiological manifestation of the dyad’s ‘shared’ emotional and behavioral experiences” (Atkinson, Jamieson, Khoury, Ludmer, & Gonzalez, 2016), as children depend on their caregivers for regulation. There is consistent evidence to suggest cortisol secretion might be synchronized among mothers and infants in both field and laboratory studies from measures of salivary cortisol (Atkinson et al., 2016). However, the small literature examining the association of parent and child hair cortisol has been mixed. For example, maternal and infant hair cortisol was not correlated at 9 or 12 months of age in a low-risk sample of Boston mothers (Liu et al., 2016), nor was it correlated in a Colorado sample of mothers and newborns (with values reflecting fetal hair cortisol) (Hoffman, D’Anna-Hernandez, Benitez, Ross, & Laudenslager, 2017). On the other hand, maternal hair cortisol at 6 and 12 months was positively correlated with infants at 12 months in another sample of Boston mothers (Flom et al., 2016). Given the small number of studies, it remains unknown whether stronger maternal–infant synchrony in hair cortisol might be observed across contexts. Sampling hair cortisol from an adverse environment provides an opportunity to examine the possible synchrony in the mother–child dyad.

2 |. PRESENT STUDY

The aim of this study was to examine maternal–infant synchrony in hair cortisol at 12 months after birth, as well as the stability of hair cortisol level over time for mothers. We focused on a “high-risk sample” given that the few studies on maternal and infant hair cortisol have been on relatively low-risk populations. Our hypothesis was that hair cortisol levels would be correlated between “high-risk” mothers and infants and that cortisol levels in mothers would be stable over time. Sociodemographic correlates and pregnancy behaviors were also examined in relation to hair cortisol values in mothers and infants.

To accomplish this, data were collected from mothers and infants participating in the Western Region Birth Cohort project. All study subjects resided in the Butantã-Jaguaré region within Western São Paulo, Brazil, a region representing 3% of the São Paulo municipality (approximately 380,000 people) (Brentani et al., 2016). A large share of these families live in favelas or “slums” within the city (Jacobi, 1994). Major environmental and social risks and poor health outcomes often occur within these communities, which include substance use, criminality, interpersonal violence, and poor nutrition (Ferri et al., 2007; Perseu Abramo Foundation Economic and Social Council, 2008). As such, these adversities have led the Brazilian government to adopt the Millennium Development Goals to improve the maternal and child health of Brazilians (Barros et al., 2010; Brentani, Fink, Bourroul, & Grisi, 2015). We characterize the mothers and infants in these communities as “high-risk” given the chronic stress experiences among these families.

3 |. METHODS

3.1 |. Participants

Between April 2012 and March 2014, a total of 6,207 children born at the University Hospital of São Paulo as well as their caregivers were enrolled in the Western Region Birth Cohort Project. The University Hospital delivers approximately 40% of births from the region overall and approximately 80% of all births covered by public health insurance. From this group, 129 children who were on average 12 months old during the present data collection were randomly selected to participate. For analysis, we relied on a sample size of 69 observations with available hair cortisol samples and hospital information. We also analyzed a subsample of 56 cases where more detailed socio-economic information was available. Due to the availability of data (hair samples and questionnaire measures on SES), our analyses relied on different sample sizes. Appendix Table A1 displays the rates of reasons for unavailable samples and the sample sizes of those available. Appendix Table A2 compares the selected sample with the broader cohort on demographic characteristics.

3.2 |. Procedures

Data collection took place through a home visit. The procedures were explained and consent was obtained prior to the hair sampling.

3.3 |. Measures

We linked hair cortisol measures to two sets of variables: birth-related variables collected within the University Hospital of São Paulo’s routine electronic data system, and socioeconomic variables collected through an in-person interview with mothers prior to hospital discharge. The hospital electronic records provided data on the maternal age at birth (in years), maternal race (as reported by the provider who delivered the baby), delivery modality (vaginal, Caesarean section, or forceps), and Apgar score immediately after birth (minute 0, 1–10 scale). With the Apgar, a score of 7 or higher refers to a good to excellent condition of the baby with respect to heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and color. As well, gestational duration (normal, preterm: <37 weeks of gestation, late term: >40 weeks of gestation), birth weight category (appropriate for gestational age, small for gestational age, large for gestational age coded according to Fenton’s [2003] revised growth charts for premature births) (Alexander, Himes, Kaufman, Mor, & Kogan, 1996), child gender, an indicator for twin status (0 = single birth, 1 = twin), and the child’s race as reported by the provider who delivered the baby were obtained.

From the postpartum interview (available for 56 mother–child dyads who agreed to participate prior to hospital release), we obtained additional information on health behaviors during pregnancy, as well as maternal socioeconomic status. Specifically, we have maternal self-report on alcohol and cigarette use during pregnancy, maternal marital status (single, married, living with partner, or widowed), maternal educational attainment (highest level attained), and monthly family income. Within Brazil, at the time of the data collection, the monthly minimum wage was R$622 (∼300 USD). In Brazil, income classifications are based on minimum wage increments, with low income being ≤2 minimum wages, average income being 2–4 minimum wages, and high income >4 minimum wages. These designations are also noted in the Tables.

3.4 |. Hair sampling

Following the signed consent of mothers, hair was sampled from the vertex posterior of the head from mothers and infants. Using sterile scissors, approximately a strip of 1.5 inches of hair was cut at the scalp from mothers and infants that had at least a hair length of 3-cm. This 3-cm length is considered to represent a 3-month retrospective measure of hair Cortisol, assuming a 1-cm/month growth rate of hair, and is a commonly used length for sampling (e.g., Russell et al., 2012; Stalder & Kirschbaum, 2012). For children, only one sample (0–3 cm from the scalp) was collected at 12 months. For mothers, a sample of a 6-cm length was collected at 12 months which was then divided into two 3-cm segments. Assuming the 1-cm/month growth of hair, the first 3-cm length of hair from the scalp for the mothers represents cortisol output from 9 to 12 months postpartum, while the length of hair 4–6 cm from the scalp for the mothers represents a cortisol output from 6 to 9 months postpartum. Samples were stored in plastic vials labeled only by ID in a locked room, and at room temperature according to storage standards (Meyer & Novak, 2012) for laboratory assay.

3.5 |. Hair processing and cortisol assay

The samples were sent for assay to the Laboratório Especializado em Análises Científicas (LEAC). Starting with ∼50 mg of hair, two washes with 40 ml of water followed by two washes with 40 ml of isopropanol on a plate rotating at 130 rpm for 3 min per wash were performed. After each set of washes, hair samples were cut into small pieces using small surgical scissors. Samples were put into disposable glass scintillation vials and HPLC grade methanol was added at a concentration of 100 μl/mg of hair. Next, samples for sonicated for 30 min followed by a 24-hr incubation period at 50°C. After incubation, samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 3,000 rpm, aliquot the supernatant into separate glass tubes and evaporated the methanol under a gentle stream of nitrogen. For samples where less than 30 mg of hair was available, smaller volumes of the extract were aliquoted, corresponding to 5, 10, or 15 mg of hair. Once the methanol was removed, the sample was resuspended in 150–250 µl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.0. Samples were vortexes for 1 min followed by another 30 s until they were well mixed. For cortisol measurement in the extracts, we used a commercially available salivary cortisol enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Cat. # KAPDB290 (CTS)—Lot 150810—DiaSource) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variance was below 10.3%.

3.6 |. Statistical analysis

Given that non-normally distributed hair cortisol values were obtained, hair cortisol values were log-transformed at each time point, as is typical with hair cortisol data (Pereg et al., 2010; Russell, Koren, Rieder, & Van Uum, 2012; Stalder, Steudte, Alexander, et al., 2012). For categorical variables such as maternal age group or race, mean level of maternal and child cortisol were computed. ANOVA models were used to test for subgroup differences. All statistical analysis was conducted using the Stata 14 Statistical software package.

4 |. RESULTS

4.1 |. Descriptives

Table 1 displays participant demographics, including race/age and socioeconomic status, pregnancy behaviors, and characteristics regarding the birth.

TABLE 1.

Descriptives of maternal, birth, and infant characteristics, and maternal pregnancy behaviors

| Cases | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at birth (years) (N = 69) | ||

| Under 20 | 9 | 13.0 |

| 20–24 | 23 | 33.3 |

| 25–29 | 16 | 23.2 |

| 30–34 | 13 | 18.8 |

| 35 and older | 8 | 11.6 |

| Maternal race (N = 69) | ||

| White | 49 | 71.0 |

| Mixed | 16 | 23.2 |

| Black | 4 | 5.8 |

| Maternal marital status (N = 56) | ||

| Single | 17 | 30.4 |

| Married | 12 | 21.4 |

| Not married, but living with partner | 26 | 46.4 |

| Widowed | 1 | 1.8 |

| Maternaleducation (N = 56) | ||

| Incomplete primary schooling | 7 | 12.5 |

| Complete primary schooling | 17 | 30.4 |

| Secondary schooling | 29 | 51.8 |

| Tertiary schooling | 3 | 5.4 |

| Family monthly income (N = 56) | ||

| R$0 to R$ 622.00 (low) | 1 | 1.8 |

| R$623.00 to R$ 1,244.00 (low) | 16 | 28.6 |

| R$ 1,245.00 to R$ 2,488.00 (average) | 27 | 48.2 |

| R$ 2,489.00 to R$ 6220.00 (average) | 10 | 17.9 |

| R$ 6,221.00 to R$ 12,440.00 (high) | 2 | 3.6 |

| Delivery modality (N = 69) | ||

| Vaginal | 35 | 50.7 |

| Caesarean | 28 | 40.6 |

| Forceps | 6 | 8.7 |

| Apgar scores at 0 min after birth (N = 69) | ||

| <8 | 4 | 5.8 |

| 8 or 9 | 38 | 55.1 |

| 10 | 27 | 39.1 |

| Maturity (N = 69) | ||

| Preterm | 2 | 2.9 |

| Full term | 67 | 97.1 |

| Birth weight category (N = 69) | ||

| Small for gestational age | 6 | 8.7 |

| Appropriate for gestational age | 60 | 87.0 |

| Large for gestational age | 3 | 4.4 |

| Single or multiple birth (N = 69) | ||

| Singleton | 67 | 97.1 |

| Twin | 2 | 2.9 |

| Child gender (N = 69) | ||

| Male | 32 | 46.4 |

| Female | 37 | 53.6 |

| Child race (N = 69) | ||

| White | 30 | 43.5 |

| Mixed | 37 | 53.6 |

| Black | 2 | 2.9 |

| Smoking in pregnancy (N = 56) | ||

| Mother did not smoke | 51 | 91.1 |

| Mother smoked at least occasionally | 5 | 8.9 |

| Drinking in pregnancy (N = 56) | ||

| Mother did not drink | 50 | 89.3 |

| Mother drank occasionally | 6 | 10.7 |

We also compared the means of maternal and child cortisol by maternal, birth, and infant characteristics and maternal pregnancy behaviors. There were no statistically significant differences in the means of cortisol values based on the characteristics measured for either mothers or children (appendix Table A3). A moderate trend was observed showing higher maternal cortisol levels among mothers with at least a secondary schooling relative to those with less schooling (F = 2.35, p = .08). These differences were statistically significant in a two-group test comparing mothers with secondary or higher education to mothers with less education (F = 8.64, p < 0.01).

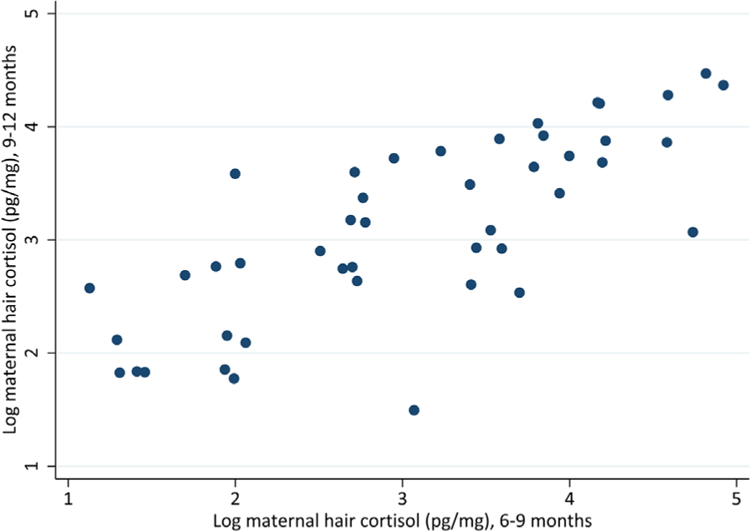

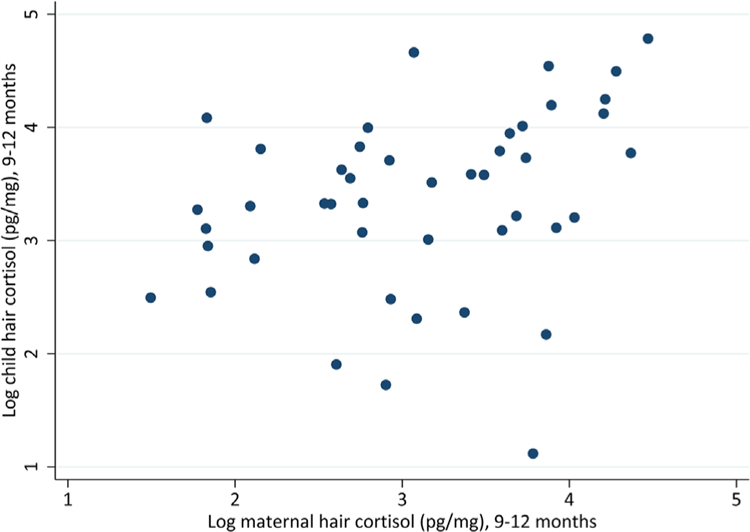

Table 2 presents mean level cortisol values in mothers and children and correlations within mother’s samples and between mothers and infants. Figures 1 and 2 displays scatterplots of key correlations. Maternal samples from the scalp, taken to reflect 6–9 months and 9–12 months of retrospective chronic stress) showed to be highly correlated (r = .78, p < .001). Mother’s hair cortisol values and infant’s values reflecting cortisol from 9 to 12 months were highly correlated (r = .62, p < .001). Maternal hair cortisol values from 6 to 9 months was also correlated with infant hair cortisol values from 9 to 12 months (r = .80, p < .001). Given extreme outliers that drove these correlations, we trimmed variables at the 95th percentile, which resulted in observations within two standard deviations of the median. In doing so, these correlations were still significant, with maternal hair cortisol across time highly correlated (r = .79, p < .001), maternal and infant hair cortisol correlated at 9–12 months (r = .61, p < .001) and maternal hair cortisol from 6 to 9 months correlated with infant hair cortisol at 9–12 months (r = .51, p < .001).

TABLE 2.

Correlations between maternal and infant hair cortisol, and display of mean level cortisol values excluding outliers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal cortisol 6–9 months | – | .79*** | .51*** |

| 2. Maternal cortisol 9–12 months | – | .61*** | |

| 3. Infant cortisol 9–12 months | – | ||

| Means (pg/mg) | 37.6 | 34.3 | 38.5 |

| Standard deviation (pg/mg) | 34.4 | 27.0 | 26.8 |

Based on cortisol measures below 130 pg/mg (excluding observations more than two standard deviations above the median). N = 63 for within-mother comparison. N = 45 for mother-child correlation at 9–12 months. N = 44 for mother at 6–9 and child at 9–12 month comparison.

p < .001.

FIGURE 1.

Scatterplots representing the natural log of maternal hair cortisol obtained from 6 to 9 months and 9 to 12 months. Excluding observations more than two standard deviations above the median

FIGURE 2.

Scatterplots representing the natural log of maternal hair cortisol obtained from 9 to 12 months and child hair cortisol from 9 to 12 months. Excluding observations more than two standard deviations above the median

5 |. DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of this study was to examine associations between maternal and infant hair cortisol in a “high-risk” sample and to determine stability in maternal cortisol over time. Notably, maternal hair cortisol was highly correlated with infant hair cortisol sampled at 12 months (r = .61, p < .001). The association between maternal and infant hair cortisol within this high-risk sample at 12 months was higher relative to previous studies even after the removal of outliers. For instance, the one other study examining maternal and infant hair cortisol at 9 and 12 months, which comprised of a largely White and highly educated sample from Boston was not found to be significant (Liu et al., 2016) nor was there a correlation in hair cortisol among a Colorado sample of newborns and their mothers (Hoffman et al., 2017). In a Boston sample that was also mostly White and highly educated, with maternal and infant hair cortisol showed a lower correlation at 12 months (r = .45, p < .001) (Flom et al., 2016).

In considering psychosocial mechanisms, one possibility is that synchrony is most strong under a high-risk context where families are faced with challenging circumstances. Within a high-risk context, mothers and children are exposed to similar stressors and, therefore, may have higher levels of cortisol (Stenius et al., 2008). A possible regulatory mechanism suggests that the stress response reflected in high hair cortisol levels within a high-risk environment may be due to early developmental attempts by the infant to cope with a high-risk environment (Debiec & Sullivan, 2014; Laurent, Ablow, & Measelle, 2011). This can occur during the prenatal period as stress signals to the developing fetus might arise from maternal exposures to hostile environments during pregnancy, thereby programming the development of the fetal HPA-axis (Kapoor, Dunn, Kostaki, Andrews, & Matthews, 2006). This is a possibility given observations of greater associations of maternal and infant salivary cortisol in households with intimate partner violence and where mothers are depressed (Hibel, Granger, Blair, Cox, & Family Life Project Key Investigators, 2009; Laurent et al., 2011). Such cortisol secretion reflecting the demands from continued stress exposure is particularly relevant to our sample of mothers and children from São Paulo given the adversities they face on a daily basis.

The high correlation between maternal and infant hair cortisol values obtained in this study, relative to the other studies on mothers and infants, point to the possibility of context as a moderator of maternal and infant hair cortisol synchrony. While we did not have any specific information on the circumstances within the timeframe reflected in the sampling—these exposures, whether they are extreme or whether they have a chronic effect on physiological synchrony (DiCorcia & Tronick, 2011) likely matter. An additional consideration is the role of maternal sensitivity on synchrony (Moore et al., 2009). A few studies have showed slightly higher synchrony among mothers with lower sensitivity (Atkinson et al., 2013; Laurent, Ablow, & Measelle, 2012). One study showed higher synchrony between maternal and 7-year-old daughters hair cortisol, under poor parenting conditions (Ouellette et al., 2015). This study did not have any specific data on maternal or dyadic experiences such as maternal sensitivity or relationship quality although this is something to be measured in conjunction with maternal–child hair cortisol in the future. Altogether, much more work examining parents and infants from high-risk contexts, their specific exposures and parenting styles, is needed to better understand the associations of maternal and infant hair cortisol.

Our study also allowed us to examine intra-individual stability in hair cortisol among mothers in our high-risk sample, with our finding reinforcing the potential of hair cortisol as a marker for chronic stress during the postpartum period. While intra-individual stability has been established before in a low-risk sample of Boston mothers across 9 and 12 months (r = .41, p < .05) (Liu et al., 2016) and in another sample of Boston mothers across 6 and 12 months (r = .28, p < .05) (Flom et al., 2016), the stability in our sample was much higher (r = .82, p < .001). In another study, correlations between .68 and .79 were found across 2- and 12-month periods among adults who had completed a study on endurance sports (Stalder, Steudte, Miller, et al., 2012). The differences in stability of values could be due to the time between samplings, and the variability of either physical or psychosocial exposures that could contribute to increased cortisol secretion over a period of time. The high correlations from our study may have been due to our use of two consecutive 3-cm samples from the same strands of hair, which could have reduced the variability in hair cortisol concentrations compared to these other studies that obtain samples from different strands. While the occurrence of specific exposures was not measured in our sample over the period of time, we speculate that stress may be more chronic in our sample, where stressful exposures (neighborhood violence, poverty) are likely to be high but invariable over time.

6 |. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Our study contains limitations that ought to be considered in the interpretation. Some features of our study limit its generalizability. No associations were observed between maternal, infant, and birth characteristics in maternal and infant cortisol values as our sample size may have been too small to detect possible correlates of hair cortisol in this population. Our data are specific to a population from one impoverished community in São Paulo, however, there is likely to be variability in the experiences of individuals within each of these communities, with respect to both risks and supports. Our study may be biased toward mothers and children who had enough hair or who were willing to have their hair sampled. While we presume that each centimeter of hair sampled reflects a 1-month time period given the prior literature, we did not have specific growth rates on each of our participants, as is generally the case with other studies that utilize hair cortisol as a measure. As the purpose of our study was to examine hair cortisol correlates across time and individuals, causality cannot be inferred. We did not assess potential moderation from either environmental or genetic factors, nor did we have access to individual and dyadic level variables such as maternal sensitivity (Flom et al., 2016; Ouellette et al., 2015), social supports, and child temperament (Groeneveld et al., 2013), all of which might may play a role in hair cortisol level.

7 |. SUMMARY

Our study raises the possibility that residing within the Brazilian slums and exposures to urban poverty and adversity are associated with increased maternal and infant synchrony in hair cortisol. We also observed high levels of intra-individual stability over time in mothers within our sample, suggesting that such stability also occurs in high-risk contexts. While specific stress exposures, individual differences in stress response, and parenting styles have yet to be identified as possible moderators to this synchrony, these findings suggest the utility of hair cortisol as a biomarker for mothers and infants in a high-risk environment. Altogether, there is potential for hair cortisol to shed light on the role of chronic stress exposure on health from early development, across development and among families, and over a variety of contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies Faculty Grant, awarded to Drs. Brentani and Fink (PI). Support for preparing this manuscript was provided through the Commonwealth Research Center (SCDMH82101008006). This project was also supported by the Health State Secretariat of São Paulo, through the CEPEDI grant.

Funding information

David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies Faculty Grant; Massachusetts Commonwealth Research Center, Grant number: SCDMH82101008006; Health State Secretariat of São Paulo—CEPEDI

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Rates and Reasons for Unavailable Data

| Cases | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Child hair samples | ||

| Hair sample collected | 52 | 40 |

| Hair was too short | 51 | 40 |

| Sick or unavailable | 5 | 4 |

| Refused | 21 | 16 |

| Total | 129 | 100 |

| Maternal hair samples | ||

| Hair sample collected | 67 | 52 |

| Hair too short | 0 | 0 |

| Sick or unavailable | 5 | 4 |

| Refused | 57 | 44 |

| Total | 129 | 100 |

| Sample sizes of available variables used for analyses | ||

| Any hair cortisol measure | 69 | 100 |

| Any hair cortisol measure and SES | 56 | 81 |

| Maternal hair cortisol | 67 | 97 |

| Maternal hair cortisol & SES | 54 | 78 |

| Child hair cortisol only | 52 | 75 |

| Child hair cortisol & SES | 41 | 59 |

| All hair cortisol measures | 50 | 100 |

| All hair cortisol measures & SES | 39 | 78 |

TABLE A2.

Demographic Characteristic Comparisons Between Analytical Sample and Broader Cohort From Which the Analytic Sample Was Drawn

| Main analytical sample, N = 56 |

Cohort sample, N = 3,811 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Cases | % | Cases | p-Value | |

| Smoked in pregnancy | 8.9 | 5 | 13.9 | 529 | 0.167 |

| Drank in pregnancy | 10.7 | 6 | 13.0 | 497 | 0.523 |

| Mother completed primary education | 30.4 | 17 | 26.6 | 1,015 | 0.532 |

| Mother completed high school or college | 57.1 | 32 | 57.3 | 2,185 | 0.959 |

| Mother is married | 21.4 | 12 | 20.5 | 783 | 0.861 |

| Mother is living with partner | 46.4 | 26 | 32.6 | 1,242 | 0.035 |

| Mother is single | 30.4 | 17 | 24.9 | 949 | 0.363 |

| HH income low (≤2 minimum wages) | 30.4 | 17 | 48.6 | 1,852 | 0.003 |

| HH income average (2–4 minimum wages) | 48.2 | 27 | 37.4 | 1,426 | 0.099 |

| HH income high (>4 minimum wages) | 21.4 | 12 | 14.0 | 533 | 0.188 |

| Household owns car | 35.7 | 20 | 37.1 | 1,412 | 0.807 |

Table compares maternal characteristics to larger sample of mothers interviewed as part of the Western Region Cohort Study (postpartum exit interview).

p-values based on two-sample equal means hypothesis.

TABLE A3.

Mean Differences of Maternal and Infant Hair Cortisol Values (Assessed at 12 Months) by Maternal, Birth, and Infant Characteristics, and Maternal Pregnancy Behaviors

| Maternal cortisol level (pg/mg) (9–12 months) | Child cortisol level (pg/mg) (9–12 months) | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at birth | ||

| Under 20 | 24.07 | 33.65 |

| 20–24 | 39.45 | 51.03 |

| 25–29 | 50.98 | 60.59 |

| 30–34 | 55.66 | 76.71 |

| 35 and older | 29.06 | 21.59 |

| Maternal race | ||

| White | 44.36 | 55.76 |

| Mixed | 39.04 | 52.33 |

| Black | 22.59 | 17.95 |

| Maternal marital status | ||

| Single | 48.26 | 66.04 |

| Married | 51.05 | 62.87 |

| Not married, but living with partner | 43.67 | 47.54 |

| Widowed | 15.81 | 21.60 |

| Mother education | ||

| Incomplete primary schooling | 26.92 | 45.40 |

| Complete primary schooling | 27.17 | 46.33 |

| Secondary schooling | 60.25 | 58.90 |

| Tertiary schooling | 68.45 | 107.40 |

| Family monthly income | ||

| R$0 to R$ 622.00 (low) | 6.28 | 19.15 |

| R$623.00 to R$ 1,244.00 (low) | 41.23 | 57.12 |

| R$ 1,245.00 to R$ 2,488.00 (average) | 46.82 | 44.82 |

| R$ 2,489.00 to R$ 6,220.00 (average) | 56.16 | 92.04 |

| R$ 6,221.00 to R$ 12,440.00 (high) | 39.38 | 12.13 |

| Delivery modality | ||

| Regular (vaginal) | 49.26 | 59.99 |

| Caesarean | 32.00 | 44.74 |

| Forceps | 47.32 | 57.59 |

| Apgar scores at 0 min after birth | ||

| <8 | 49.68 | 32.84 |

| 8 or 9 | 40.59 | 56.74 |

| Regular (vaginal) 49.26 59.99 | ||

| Regular (vaginal) 49.26 59.99 | ||

| Forceps 47.32 57.59 | ||

| Forceps 47.32 57.59 | ||

| 10 | 42.50 | 50.77 |

| Maturity | ||

| Preterm | 52.69 | 45.52 |

| Full term | 41.54 | 53.01 |

| Birth weight category | ||

| Small for gestational age | 57.34 | 69.74 |

| Appropriate for gestational age | 40.81 | 49.93 |

| Large for gestational age | 31.39 | 73.11 |

| Single or multiple birth | ||

| Singleton | 42.38 | 52.72 |

| Twin | 8.61 | 52.94 |

| Child gender | ||

| Male | 40.91 | 46.18 |

| Female | 42.70 | 58.79 |

| Child race | ||

| White | 50.26 | 61.86 |

| Mixed | 35.89 | 45.01 |

| Black | 27.84 | 26.47 |

| Smoking in pregnancy | ||

| Mother did not smoke | 47.20 | 57.98 |

| Mother smoked at least occasionally | 33.87 | 42.92 |

| Drinking in pregnancy | ||

| Mother did not drink | 46.91 | 58.10 |

| Mother drank occasionally | 38.43 | 41.84 |

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, & Kogan M (1996). A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 87(2), 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman SB, Dawson G, Panagiotides H, Yamada E, & Wilkinson CW (2002). Stress hormone levels of children of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 14(2), 333–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson L, Gonzalez A, Kashy DA, Santo Basile V, Masellis M, Pereira J, … Levitan R (2013). Maternal sensitivity and infant and mother adrenocortical function across challenges. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(12), 2943–2951. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson L, Jamieson B, Khoury J, Ludmer J, & Gonzalez A (2016). Stress physiology in infancy and early childhood: Cortisol flexibility, attunement and coordination. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 28(8), 1–12. 10.1111/jne.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros FC, Matijasevich A, Requejo JH, Giugliani E, Maranhão AG, Monteiro CA, … Victora CG (2010). Recent trends in maternal, newborn, and child health in Brazil: Progress toward Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1877–1889. 10.2105/AJPH2010.196816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PA, Pargas R, Walker EF, Green P, Newport DJ, & Stowe Z (2008). Maternal depression and infant cortisol: Influences of timing, comorbidity and treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 49(10), 1099–1107. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01914.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentani A, Fink G, Bourroul ML, & Grisi SJ (2015). Assessing the effectiveness of Sao Paulo’s policy efforts in lowering teenage pregnancies and associated adverse birth outcomes. Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health, 02(02), 151 10.4172/2376-127X1000151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brentani A, Grisi SJFE, Taniguchi MT, Ferrer APS, de Moraes Bourroul ML, & Fink G (2016). Rollout of community-based family health strategy (programa de saude de familia) is associated with large reductions in neonatal mortality in São Paulo, Brazil. SSM—Population Health, 2, 55–61. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clearfield MW, Carter-Rodriguez A, Merali A-R, & Shober R (2014). The effects of SES on infant and maternal diurnal salivary cortisol output. Infant Behavior & Development, 37(3), 298–304. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J, & Sullivan RM (2014). Intergenerational transmission of emotional trauma through amygdala-dependent mother-to-infant transfer of specific fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(33), 12222–12227. 10.1073/pnas.1316740111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCorcia JA, & Tronick E (2011). Quotidian resilience: Exploring mechanisms that drive resilience from a perspective of everyday stress and coping. Neuroscience & Biobehavoral Reviews, 35(7), 1593–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri CP, Mitsuhiro SS, Barros MCM, Chalem E, Guinsburg R, Patel V, … Laranjeira R (2007). The impact of maternal experience of violence and common mental disorders on neonatal outcomes: A survey of adolescent mothers in Sao Paulo, Brazil. BMC Public Health, 7, 209 10.1186/1471-2458-7-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton TR (2003). A new growth chart for preterm babies: Babson and Benda’s chart updated with recent data and a new format. BMC Pediatrics, 3(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flom M, St John AM, Meyer JS, & Tarullo AR (2016). Infant hair cortisol: Associations with salivary cortisol and environmental context. Developmental Psychobiology, 59(1), 26–38. 10.1002/dev.21449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld MG, Vermeer HJ, Linting M, Noppe G, van Rossum EFC, & van IJzendoorn MH (2013). Children’s hair cortisol as a biomarker of stress at school entry. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 16(6), 711–715. 10.3109/10253890.2013.817553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibel LC, Granger DA, Blair C, Cox MJ, & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2009). Intimate partner violence moderates the association between mother-infant adrenocortical activity across an emotional challenge. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 23(5), 615–625. 10.1037/a0016323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MC, D’Anna-Hernandez K, Benitez P, Ross RG, & Laudenslager ML (2017). Cortisol during human fetal life: Characterization of a method for processing small quantities of newborn hair from 26 to 42 weeks gestation. Developmental Psychobiology, 59(1), 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi P (1994). Households and environment in the city of Sao Paulo: Problems, perceptions and solutions. Environment and Urbanization, 6(2), 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A, Dunn E, Kostaki A, Andrews MH, & Matthews SG (2006). Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: Prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. The Journal of Physiology, 572(Pt 1), 31–44. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlén J, Frostell A, Theodorsson E, Faresjö T, & Ludvigsson J (2013). Maternal influence on child HPA axis: A prospective study of cortisol levels in hair. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1333–e1340. 10.1542/peds.2013-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Ablow JC, & Measelle J (2011). Risky shifts: How the timing and course of mothers’ depressive symptoms across the perinatal period shape their own and infant’s stress response profiles. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 521–538. 10.1017/S0954579411000083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Ablow JC, & Measelle J (2012). Taking stress response out of the box: Stability, discontinuity, and temperament effects on HPA and SNS across social stressors in mother-infant dyads. Developmental Psychology, 48(1), 35–45. 10.1037/a0025518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Snidman N, Leonard A, Meyer J, & Tronick E (2016). Intra-individual stability and developmental change in hair cortisol among postpartum mothers and infants: Implications for understanding chronic stress. Developmental Psychobiology, 58(4), 509–518. 10.1002/dev.21394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, & McEwen BS (2000). Child’s stress hormone levels correlate with mother’s socioeconomic status and depressive state. Biological Psychiatry, 48(10), 976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JS, & Novak MA (2012). Minireview: Hair cortisol: A novel biomarker of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical activity. Endocrinology, 153(9), 4120–4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GA, Hill-Soderlund AL, Propper CB, Calkins SD, Mills-Koonce WR, & Cox MJ (2009). Mother-infant vagal regulation in the face-to-face still-face paradigm is moderated by maternity sensitivity. Child Development, 80(1), 209–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette SJ, Russell E, Kryski KR, Sheikh HI, Singh SM, Koren G, & Hayden EP (2015). Hair cortisol concentrations in higher- and lower-stress mother-daughter dyads: A pilot study of associations and moderators. Developmental Psychobiology, 57(5), 519–534. 10.1002/dev.21302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer FB, Anand KJS, Graff JC, Murphy LE, Qu Y, Völgyi E, … Tylavsky FA (2013). Early adversity, socioemotional development, and stress in urban 1-year-old children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 163(6), 1733–1739e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg D, Gow R, Mosseri M, Lishner M, Rieder M, Van Uum S, & Koren G (2011). Hair cortisol and the risk for acute myocardial infarction in adult men. Stress, 14(1), 73–81. 10.3109/10253890.2010.511352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perseu Abramo Foundation Economic and Social Council. (2008). Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, E/C.12/BRA/2.:32 United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Rippe RCA, Noppe G, Windhorst DA, Tiemeier H, van Rossum EFC, Jaddoe VWV, .. . van den Akker ELT. (2016). Splitting hair for cortisol? Associations of socio-economic status, ethnicity, hair color, gender and other child characteristics with hair cortisol and cortisone. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 66, 56–64. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell E, Koren G, Rieder M, & Van Uum S (2012). Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: Current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(5), 589–601. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, & Kirschbaum C (2012). Analysis of cortisol in hair-state of the art and future directions. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26(7), 1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Steudte S, Alexander N, Miller R, Gao W, Dettenborn L, & Kirschbaum C (2012). Cortisol in hair, body mass index and stress-related measures. Biological Psychology, 90(3), 218–223. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Steudte S, Miller R, Skoluda N, Dettenborn L, & Kirschbaum C (2012). Intraindividual stability of hair cortisol concentrations. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(5), 602–610. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenius F, Theorell T, Lilja G, Scheynius A, Alm J, & Lindblad F (2008). Comparisons between salivary cortisol levels in six-months-olds and their parents. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(3), 352–359. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, & Gunnar MR (2006). Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior, 50(4), 632–639. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghri Z, Guhn M, Weinberg J, Grunau RE, Yu W, & Hertzman C (2013). Hair cortisol reflects socio-economic factors and hair zinc in preschoolers. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(3), 331–340. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart J, Noppe G, van Rossum EFC, Koper JW, Raat H, & van den Akker ELT (2016). Socioeconomic status in children is associated with hair cortisol levels as a biological measure of chronic stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 65, 9–14. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosu AC, Valdimarsdóttir U, Shields AE, Williams DR, & Williams MA (2013). Correlates of cortisol in human hair: Implications for epidemiologic studies on health effects of chronic stress. Annals of Epidemiology, 23(12), 797–811.e2. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J, Stevens B, de Silva N, Gibbins S, Beyene J, Taddio A, … Koren G (2007). Hair cortisol as a potential biologic marker of chronic stress in hospitalized neonates. Neonatology, 92(1), 42–49. 10.1159/000100085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]