ABSTRACT

Target of Rapamycin (TOR) regulates multiple growth- and metabolic-related processes in Arabidopsis thaliana as in all other eukaryotes. While several of these processes have been investigated in diverse Arabidopsis growth stages, little is known about hormonal and metabolic regulation of TOR during seed germination. This is mainly due to the fact that Arabidopsis knockout lines of TOR are embryo lethal. Here, we utilized the knockout lines of TOR-interacting protein, REGULATORY-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN OF TOR 1B (RAPTOR1B), to perform comprehensive hormone profiling during seed germination. We previously reported that RAPTOR1B positively regulates seed germination by maintaining the nutritional and hormonal balance. In the current analysis, dry and imbibed seeds as well as germinated seeds were subjected to detailed hormone analysis. Accordingly, the abscisic acid content of dry and imbibed raptor1b seeds was higher than that of WT, while the amounts of gibberellins were comparable after stratification. Further analysis showed that raptor1b seeds maintained higher levels of indole-3-acetic acid and jasmonates, namely jasmonic acid (JA) and 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid, even after stratification. The combination of this hormonal perturbation seems to be the driving factor for the observed delayed germination phenotypes in raptor1b seeds.

KEYWORDS: RAPTOR1B, Arabidopsis, germination, hormones, dormancy, ABA, IAA, jasmonates, hormone cross-talk

Overview

Plant germination, growth, and development are the results of interaction between environmental cues and diverse endogenous signals.1 A key regulator that integrates cellular growth in response to external stimuli is TOR, which is well conserved among all eukaryotes and thoroughly studied in animals and yeast.2,3 TOR assembles into two protein complexes commonly termed TOR complex 1 and 2 (TORC1 and TORC2).4 Plants seem to only contain the core members of TORC1, namely RAPTOR and lethal with sec thirteen protein 8 (LST8).5,6 One TOR gene, two RAPTOR genes (RAPTOR1A and RAPTOR1B), and two LST8 genes (LST8-1 and LST8-2) have been annotated from the Arabidopsis genome.5–8 Both RAPTOR genes are actively transcribed, while only LST8-1 seems to be actively expressed.5,6,8 Additionally, raptor1b (At3g08850) and lst8-1 (At3g18140) mutants show significant and almost similar growth, developmental and metabolic phenotypes.5,6,9 Moreover, disruption of the RAPTOR1A has no visible phenotypes,8 while the lack of detectable expression of LST8-2 indicated that it is a nonfunctional gene.5

As mentioned earlier, TOR acts as a central hub that is involved in multiple processes associated with plant growth and proliferation.10 In contrast to the embryo lethality of tor-mutant lines, the knockout lines of the TOR-interacting partners, RAPTOR1B (At3g08850) and LST8-1 (At3g18140), are viable.5,6 Arabidopsis eFP Browser data suggested the preferential expression of TOR complex genes, namely TOR, RAPTOR1B, and LST8-1 in dry seeds, indicating potential roles of the TOR complex in developing and maturating seeds.11 In recent papers, the consequences of RAPTOR1B mutation on seed and vegetative tissue physiology and metabolism were investigated.9,12 RAPTOR1B was reported to control some physiological and molecular aspects of Arabidopsis seeds and vegetative tissue to maintain the proper morphology, anatomy, and metabolic content.9,12 Previous data revealed that TOR is a key player in regulating phytohormone signaling pathways in Arabidopsis growth in leaf and root tissues.13–17 However, little is known about RAPTOR1B function during the process of seed germination. Here, we report that RAPTOR1B modulates hormonal homeostasis during seed germination. We analyzed the hormone content of WT Arabidopsis seeds and raptor1b during the different germination stages. For this purpose, we harvested samples from six stages, namely, dry seeds, seeds after 72 h of imbibition at 4°C and 1, 2, 3, and 4 days after imbibition. The later samples represent seeds that were already germinated. Results of this analysis revealed that the high abscisic acid (ABA), indole acetic acid (IAA), and jasmonic acid (JA) constitute the central node for the observed delayed germination of raptor1b seeds.

Mutation of RAPTOR1B delays seed germination

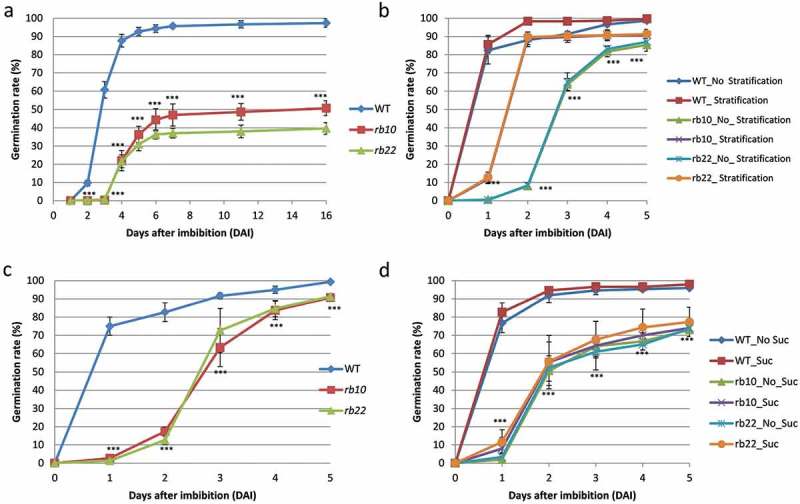

Based on the recently published phenotypic observations of raptor1b seeds,12 we further dissected the role of RAPTOR1B during Arabidopsis seed germination. For this purpose, we employed the same two independent raptor1b lines (rb10 and rb22) that were used in our previous study,12 and compared them to their respective WT. To investigate the effect of RAPTOR1B on seed dormancy, the germination rate of freshly harvested seeds of WT and raptor1b was scored. It became obvious that the germination rate of raptor1b seeds was significantly lower than WT without stratification treatment (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Delayed germination of raptor1b seeds.

A. raptor1b seeds have altered dormancy. Germination rate was scored from freshly harvested, non-stratified seeds. B. Germination of fully after-ripened WT and raptor1b seeds with or without stratification treatment. C. External application of nitrate did not improve the germination of raptor1b seeds. D. raptor1b seeds showed delayed germination with or without external supplementation of sucrose. Error bars indicate mean ± SD for 5 biological replicates. Black asterisks indicate significantly different from WT (P< .001, Student’s t-test). Stratification refers to seeds that have been kept for 3 days at 4°C. Values of germination percentages are from at least 5 biological replicates of 100 seeds each (100 seeds/plate/5 replicates).

Previous studies have shown that dormancy can be released by extended dry seed storage (after-ripening) or stratification treatment at low temperature.18,19 Therefore, we also investigated the effect of three month-dry storage with or without stratification. Without stratification, only 1% of the raptor1b seeds germinated on the first day after imbibition (DAI) compared to 82% germination efficiency of WT seeds. Interestingly, raptor1b seeds reached the 82% germination efficiency only after 4 DAI (Figure 1(b)). When seeds, that were fully after-ripened, were stratified for 3 days, the delayed germination of raptor1b seeds was reduced from 3 to 1 DAI. Accordingly, 10% of the raptor1b seeds germinated 1 DAI compared to 86% germination efficiency of WT seeds; however, after-ripened and stratified raptor1b seeds reached the 89% germination efficiency 2 DAI (Figure 1(b)). This indicates that the differences between WT and raptor1b seeds decreased significantly with stratification.

It was also reported that nitric oxide (NO), triggered by CN2, nitrate, or nitrite, promotes a loss of dormancy.20,21 Nitrate can inhibit ABA synthesis and enhance ABA catabolism; therefore, we also investigated the effect of external application of 7 mM KNO3.21 The results of the time-course germination scoring showed that nitrate treatment was not able to improve the germination rate of raptor1b seeds (Figure 1(c)). Additionally, we reported previously that raptor1b seeds showed significantly lower sucrose level in their dry seeds,12 which prompted us to test the influence of external application of sucrose on the germination rate. Surprisingly, contrary to the increased greening efficiency of etiolated raptor1b seedlings after sucrose feeding,22 no differences were detected in the germination efficiencies of raptor1b seeds with or without sucrose supplementation (Figure 1(d)). Accordingly, it can be concluded that raptor1b seeds germinated slower and at a lower frequency compared to WT seeds even in presence of sucrose, indicating that this phenotype is, contrary to the sugar-dependent greening after extended etiolation,22 a sugar-independent phenotype (Figure 1(d)). Furthermore, raptor1b seeds showed, beyond their delayed germination, less vitality, consistent with our previous observation.12

RAPTOR1B controls hormonal balance during seed germination

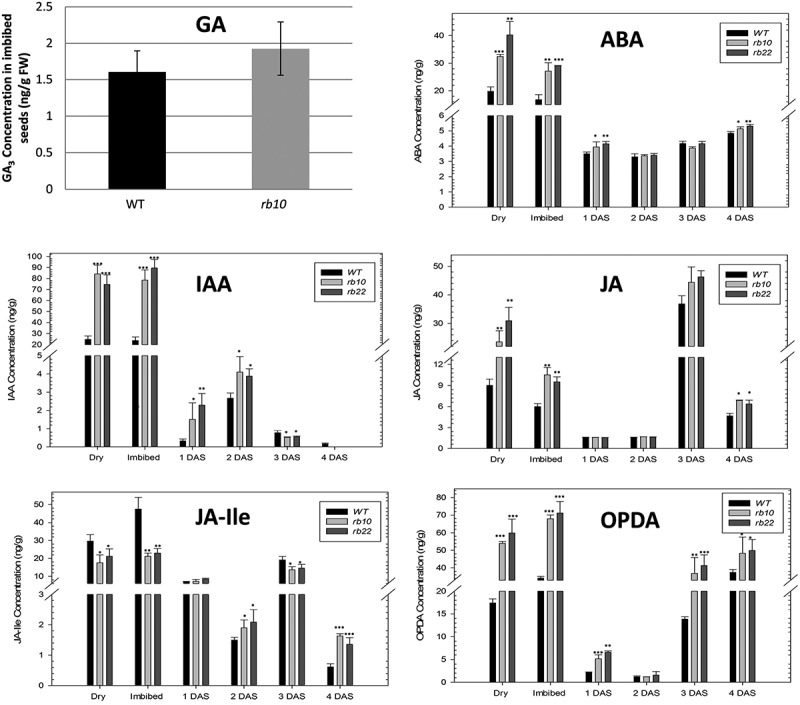

We previously showed that a mutation in RAPTOR1B is associated with perturbation of hormonal levels especially increased levels of ABA, IAA, and jasmonates.12 In the previous publication,12 we were not able to quantify gibberellins (GAs) level in dry seeds due to their low concentration. The endogenous level of the bioactive GA (GA4) is often not detectable in dry Arabidopsis seeds even if additional sample purification steps are employed.23 However, we have shown that external GA application can partially rescue the delayed germination phenotypes of raptor1b seeds.12 It is known that stratification of Arabidopsis seeds is associated with increased GA level.24 Therefore, we repeated our analysis, starting from 200 mg of stratified seed material and included three solid phase extraction (SPE) steps,23 to purify and enrich for GA. Because of the phenotypic similarity between the two raptor1b lines,12 only one line (rb10) was chosen for the extraction, purification, and analysis of GA. Intriguingly, the endogenous level of GA did not show significant changes between raptor1b and WT seeds (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quantification of hormones in raptor1b and WT seeds.

Error bars indicate mean ± SD for 5 biological replicates. Black asterisks indicate significantly different from WT (*P< .05, **P< .01, ***P< .001, Student’s t-test).

To obtain an overview of other hormonal changes occurring during the transition from dry seeds to imbibed seeds as well as the dynamics during germination, we comprehensively analyzed the hormone levels of WT and raptor1b dry, imbibed, and germinated seeds. ABA levels decreased partially with seed imbibition in WT seeds, this was also true for raptor1b seeds (Figure 2). However, raptor1b showed massively increased ABA level in both dry and imbibed seeds. This level stayed also significantly higher after one day of seed germination. Interestingly, after radical emergence and cotyledon growth, both WT and rb seeds reached similar level. IAA levels did not change with seed imbibition in WT and raptor1b seeds. However, raptor1b showed significantly higher IAA level in both dry and imbibed seeds. This level significantly decreased after one day of seed germination. raptor1b seeds showed higher IAA level at 1 and 2 DAS. JA and its precursor OPDA showed also significantly higher level in both dry and imbibed seeds (Figure 2).

Conclusion and perspectives

The hormones ABA and GA are known to control seed germination through antagonistic action, where ABA promotes seed dormancy and inhibits germination, while GA pursues the opposite. Previous data showed that the ABA/GA ratio, rather than the absolute amount of ABA or GA, plays a crucial role in releasing dormancy and promoting germination.25

In the present study, the raptor1b seeds showed a delayed germination phenotype of fresh seeds but also with seeds that were subjected to a 3-month dry storage. This delayed germination was partially improved by stratification. Furthermore, stratification reduces ABA content in the same way in both WT and raptor1b seeds. However, raptor1b imbibed seeds have significantly higher ABA level (~1.6–1.7 fold increase) than WT. Contrary to the high ABA level in seeds, recent data showed that lst8 and raptor1b mutants showed a significantly decreased ABA level in vegetative tissue, indicating the tissue specificity of RAPTOR1B hormonal regulation.9,26 Beyond the differential ABA concentrations, the GA level in WT and raptor1b seeds was overall comparable, indicating that the increased ABA/GA ratio is most likely a result of higher ABA levels in the mutant seeds. Accordingly, this hormonal measurement seems to reveal that the increased ABA level in dry raptor1b seeds contributed to the delayed germination phenotype.

Other hormones have been reported to crosstalk with ABA and/or GA.27 Auxins, for example, induced ABA-dependent seed dormancy,28 while JA and its metabolites are also known to have a negative impact on seed germination.18,29 Accordingly, the emerging finding concerning the hormonal crosstalk of other germination-delaying hormones, namely, IAA and JA support the speculation that the hormonal imbalance associated to these three hormonal classes, was the most obvious molecular phenotype of raptor seeds.

During seed development, diverse compounds accumulated including proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates.30 Reserve mobilization and metabolism activation start upon imbibition.31 This metabolic activation is influenced also by hormonal levels. For instance, it was shown that lipid mobilization is repressed by ABA INSENSITIVE4 (ABI4) during germination.32 Previous data showed that seed imbibition was associated with reduction in most seed metabolites that implies the support of a metabolic switch toward seed germination.33 Our recent report indicated that raptor1b showed higher accumulation of amino acids and sugars in their dry seeds.12 This result indicates that, even though raptor1b seeds contained sufficient amount of reserve nutrients, they were unable to efficiently utilize these to support their efficient germination. This indicates that the availability of nutrients per se is not the limiting factor for the delayed germination. Apparently, hormonal imbalance controls or correlates with the inability of raptor1b seeds to efficiently metabolize their reserve nutrients.

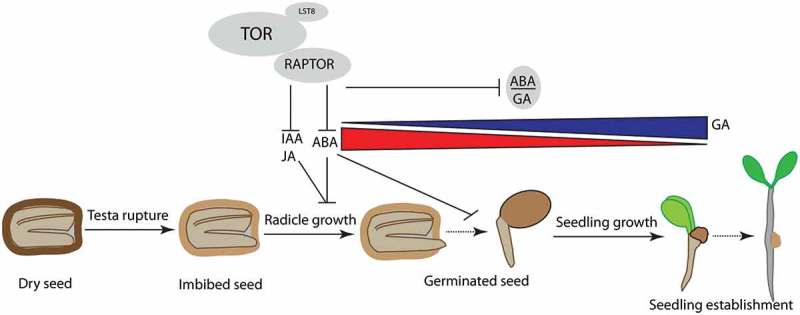

Taken together, the present study confirms that RAPTOR1B and hence TOR9 positively regulate seed germination by maintaining the hormonal balance, specifically the ABA/GA ratio and the content of other germination-delaying hormones such as IAA and JA.28,34,35 Further, this study suggests and opens the possibility that RAPTOR1B plays crucial and complex roles in the cross-talk between hormones during germination; however, more detailed molecular dissection is necessary to obtain a deeper understanding of this cross-talk and the driving forces behind it (Figure 3). Here especially metabolic and hormonal profiling associated to detailed proteomic and transcriptomic studies during the stages of developing seeds (seed maturation), where most of the reserve accumulation is happening, in addition to the transition from seed maturation to seed desiccation might provide more detailed insight.

Figure 3.

RAPTOR1B positively regulates seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1.Rymen B, Sugimoto K.. Tuning growth to the environmental demands. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN.. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimobayashi M, Hall MN. Making new contacts: the mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat Reviews Mol Cell Bio. 2014;15:155–162. doi: 10.1038/nrm3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreau M, Azzopardi M, Clement G, Dobrenel T, Marchive C, Renne C, Martin-Magniette M-L, Taconnat L, Renou J-P, Robaglia C, et al. Mutations in the Arabidopsis homolog of LST8/GbetaL, a partner of the target of Rapamycin kinase, impair plant growth, flowering, and metabolic adaptation to long days. Plant Cell. 2012;24:463–481. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.091306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson GH, Veit B, Hanson MR. The Arabidopsis AtRaptor genes are essential for post-embryonic plant growth. BMC Biol. 2005;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menand B, Desnos T, Nussaume L, Berger F, Bouchez D, Meyer C, Robaglia C. Expression and disruption of the Arabidopsis TOR (target of rapamycin) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6422–6427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092141899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deprost D, Truong HN, Robaglia C, Meyer C. An Arabidopsis homolog of RAPTOR/KOG1 is essential for early embryo development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salem MA, Li Y, Bajdzienko K, Fisahn J, Watanabe M, Hoefgen R, Schöttler MA, Giavalisco P. RAPTOR controls developmental growth transitions by altering the hormonal and metabolic balance. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:565–593. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong Y, Sheen J. Novel links in the plant TOR kinase signaling network. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2015;28:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart NJ. An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One. 2007;2:e718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salem MA, Li Y, Wiszniewski A, Giavalisco P. Regulatory-associated protein of TOR (RAPTOR) alters the hormonal and metabolic composition of Arabidopsis seeds, controlling seed morphology, viability and germination potential. Plant J. 2017;92:525–545. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong P, Xiong F, Que Y, Wang K, Yu L, Li Z, Ren M. Expression profiling and functional analysis reveals that TOR is a key player in regulating photosynthesis and phytohormone signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:677. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong F, Zhang R, Meng Z, Deng K, Que Y, Zhuo F, Feng L, Guo S, Datla R, Ren, M. Brassinosteriod Insensitive 2 (BIN2) acts as a downstream effector of the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway to regulate photoautotrophic growth in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2017;213:233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng K, Yu L, Zheng X, Zhang K, Wang W, Dong P, Zhang J, Ren M. Target of rapamycin is a key player for auxin signaling transduction in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:291. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song Y, Zhao G, Zhang X, Li L, Xiong F, Zhuo F, Zhang C, Yang Z, Datla R, Ren M, et al. The crosstalk between Target of Rapamycin (TOR) and Jasmonic Acid (JA) signaling existing in Arabidopsis and cotton. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45830. doi: 10.1038/srep45830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrada A, Montane MH, Robaglia C, Menand B. Spatial regulation of root growth: placing the plant tor pathway in a developmental perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:19671–19697. doi: 10.3390/ijms160819671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dave A, Vaistij FE, Gilday AD, Penfield SD, Graham IA. Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana seed dormancy and germination by 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:2277–2284. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penfield S, Josse EM, Kannangara R, Gilday AD, Halliday KJ, Graham IA. Cold and light control seed germination through the bHLH transcription factor SPATULA. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1998–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bethke PC, Libourel IG, Aoyama N, Chung YY, Still DW, Jones RL. The Arabidopsis aleurone layer responds to nitric oxide, gibberellin, and abscisic acid and is sufficient and necessary for seed dormancy. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1173–1188. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali-Rachedi S, Bouinot D, Wagner MH, Bonnet M, Sotta B, Grappin P, Jullien M. Changes in endogenous abscisic acid levels during dormancy release and maintenance of mature seeds: studies with the cape verde islands ecotype, the dormant model of arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2004;219:479–488. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, McFarlane HE, Obata T, Richter AS, Lohse M, Grimm B, Persson S, Fernie AR, Giavalisco P. Inhibition of TOR represses nutrient consumption, which improves greening after extended periods of etiolation. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:101. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo M, Jikumaru Y, Kamiya Y. Profiling of hormones and related metabolites in seed dormancy and germination studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;773:99–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-231-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finch-Savage WE, Leubner-Metzger G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 2006;171:501–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gazzarrini S, Tsai AYL. Hormone cross-talk during seed germination. Essays Biochem. 2015;58:151–164. doi: 10.1042/bse0580151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montane MH, Menand B. ATP-competitive mTOR kinase inhibitors delay plant growth by triggering early differentiation of meristematic cells but no developmental patterning change. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:4361–4374. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gazzarrini S, Tsai AY. Hormone cross-talk during seed germination. Essays Biochem. 2015;58:151–164. doi: 10.1042/bse0580151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Feng Z, Li Q, Yang HQ, Luan S, Li J, He Z-H. Auxin controls seed dormancy through stimulation of abscisic acid signaling by inducing ARF-mediated ABI3 activation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:15485–15490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304651110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasternack C, Strnad M. Jasmonate signaling in plant stress responses and development - active and inactive compounds. N Biotechnol. 2016; 33:604–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han C, Yang P. Studies on the molecular mechanisms of seed germination. Proteomics. 2015;15:1671–1679. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu Q, Wang B-C, Jin X, Li H-B, Han P, Wei K-H, Zhang X-M, Zhu Y-X. Proteomic analysis and extensive protein identification from dry, germinating arabidopsis seeds and young seedlings. BMB Rep. 2005;38:650–660. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2005.38.6.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penfield S, Li Y, Gilday AD, Graham S, Graham IA. Arabidopsis ABA INSENSITIVE4 regulates lipid mobilization in the embryo and reveals repression of seed germination by the endosperm. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1887–1899. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fait A, Angelovici R, Less H, Ohad I, Urbanczyk-Wochniak E, Fernie AR, Galili G. Arabidopsis seed development and germination is associated with temporally distinct metabolic switches. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:839–854. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasternack C, Hause B. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann Bot. 2013;111:1021–1058. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dave A, Graham IA. Oxylipin signaling: a distinct role for the jasmonic acid precursor cis-(+)-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (cis-OPDA). Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:42. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.