William Fletcher Hoyt, considered to represent the pinnacle of neuro-ophthalmology,1 helping to define as well as expand the field, passed away on March 20th 2019, at the Alta Bates Hospital in Berkeley, California where he had been born nearly 93 years earlier to a mother who was a nurse there and where his father practised medicine.

During his lifetime, Bill Hoyt, as he went by, accomplished numerous feats in his chosen field, earning him accolades such as “titan of the field,” “definer of modern neuro-ophthalmology,” “acme of neuro-ophthalmologists,” “master teacher,” and, as a sign of respect reserved for the most knowledgeable of physicians,“Toughy Hoyt” by contemporary luminary, J. Lawton Smith.1–4 During Bill Hoyt’s long tenure at UCSF Medical Center in San Francisco, where he had gone to medical school and thereafter trained in ophthalmology before eventually joining the faculty in 1958, he trained over 71 full-year fellows, more partial-year fellows, 300 residents and myriad medical students. Most of his fellows became full professors, well over a dozen, Chairs, and, a couple Deans; many also writing reference textbooks or becoming senior editors of journals. For his extraordinary contributions to ophthalmology, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Medicine from Sweden’s Karolinska Institute committee, which also awards the Nobel prize.

He published over 274 manuscripts, several of them listed as some of the 100 most important articles ever published in the field of ophthalmology. His collaboration with Frank B. Walsh in expanding the third edition of the book we now call Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, in 1969, and today in its sixth edition, was a milestone leading to vastly increased and accessible knowledge of the field. His ongoing scientific creativity and productivity led to not one, but three, formal Festschrifts, at the ages of 60, 70 and 75, with special tributes also organised at the International Neuro-Ophthalmology Society (INOS) meeting in 2010 in France for his 84th birthday and then again at the next and final INOS meeting for his 86th birthday in Singapore.3,5,6 Formal symposiums were organised in his honour at the American Academy of Ophthalmology and an annual lecture series established in his name in 2001 in conjunction with the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society (NANOS).3 With his first manuscript appearing in 1955, and his last, highly cited work in 2015, his publications bookend a highly productive academic career spanning over 60 years.

How did he do it?

As is true for all people, Bill Hoyt was a product of his surrounding and times. And as for all individuals, he made certain decisions as to how best make use of the opportunities presented to him.

Born into a family with a kindly physician father, Werner, and an attentive nurse mother, Grace, Bill Hoyt was one of three children. His twin brother Fletcher became a renowned mountaineering pioneer and skier, and eventually settled to become an instructor in forestry at the College of the Siskiyous near Mt. Shasta. His sister Peggy became a San Francisco attorney. Bill greatly enjoyed the “biosphere” of the Bay Area, as he put it, with a refined sense for not only academic pursuits, but also the arts as well as athletics. Bill’s father emphasised to him the value of commencing projects rather than ruminating over them (he had a sign placed above Bill’s headboard that stated “Do it now!”). Bill, following this advice, would later advise his students to get at least some aspect of any project undertaken accomplished every day. During childhood and until graduating from high school, he took up partnered skating to win the National Championship with Marilyn Grace (Figure 1). He attended UC Berkeley on a Navy scholarship at the tail end of WWII (Figure 2). He afterwards spent long hours on transport ships to and from Japan, where he took an interest in intricate woodcarving and in knives, eventually building a fine collection of daggers and swords. A pair of quality binoculars purchased for him by his father for his sea voyages were kept and used throughout life to observe ships from the large magnificent windows of his hillside home living room overlooking the Sausalito bay. An enduring fondness for Japanese culture had him visit the country later over 24 times for meetings and lecture series during his professional career. Carefully selected simple, and yet exquisite, Japanese art was brought back to decorate his house and office. His manual and artistic skills were obvious with a notable interest in calligraphy (unlike most physicians, his clinic notes and illustrations were notable for clarity) and during his ophthalmology residency, he set a record for being the most accomplished resident cataract surgeon in the department’s history. However, as he said in a remarkably informative interview with Lanning B. Kline that could serve as an ode to fellowship training for others (containing much information “between the lines”),3 he wished to occupy not only his hands, but his mind as well, and so chose a subspecialty that would allow him to be creative in this aspect as well.

Figure 1.

Bill Hoyt with high school skating partner Marilyn Grace, 1944 Pacific Coast and National Champions.

Figure 2.

Bill in the Navy, with his twin brother, Fletcher, in the Army.

That subspecialty would be neuro-ophthalmology and he had received a 1956–57 Fulbright scholarship to go study at the University of Vienna following his residency under Frederick C. Cordes. Though he found it not as academically challenging as he had hoped it might be, he found the year in Vienna to be extremely enriching. An excellent skier, he often went skiing and socialising, he improved his German and eventually met his future wife, Johanna. As is often true for those able to live for a period of time outside their home country, it became an eye opening and transformative experience (Figure 3). By living in another country, not long previously considered to be an enemy state, he learned how to respect other cultures different from his own and to see the value they could bring to an individual. Bill learned to appreciate colleagues from many different countries, in Europe, the Far East and elsewhere, and forged many lifelong friendships. Just as importantly, he recognised the potential and value of training bright individuals from other countries to go back and train others. This was to prove to be a crucial insight later elevating his career to make him a genuine doctor, that is to say, a scholar and a teacher, on a truly global scale.

Figure 3.

Facing the Matterhorn, Zermatt, Switzerland, June 1953.

Another break had come just prior to his departure for Vienna, with a visit by Frank B. Walsh to UCSF. Bill had been assigned as the resident to accompany Dr. Walsh to his lectures and campus events, and their interactions made it clear to him that spending more time with this individual, widely considered to be the father of neuro-ophthalmology, having just published the first bona fide textbook in the field nine years earlier, would be a most fruitful endeavour. With Cordes’ blessing, he was able to extend his leave following his training in Vienna by another year, to do a second fellowship with Frank Walsh in Baltimore before returning to UCSF.

When Bill Hoyt arrived from Vienna to Baltimore, he found himself to be at what was the centre of ophthalmological training at the time, the Wilmer Eye Institute of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, headed by A. Edward Maumenee. “It was THE place to be,” said Bill, “where the action was.” He found the overall academic experience spectacular, stating also that he never learned so much from one person in one year. Walsh’s second fellow, he felt he was treated as a son, with Walsh challenging him while nurturing him as he could. During this same year, another fortuitous encounter occurred, which was to provide Bill with a kindred competitive spirit and further drive for excellence throughout his career. A dazzling Wilmer senior resident, J. Lawton Smith, was there, preparing to do his neuro-ophthalmology fellowship training under the illustrious and esteemed David G. Cogan in Boston. The friendship and competitive spirit that would emerge from this year together became another fuel propelling both contemporaries to reach new heights of discovery, teaching and excellence throughout their careers.

Bill was nonetheless happy to be able to return to San Francisco, with a position awaiting him in the neurosurgical division at UCSF, while seeing ophthalmological patients part-time in Frederick Cordes’ private ophthalmological office. With literally no office space assigned to him at all, he set up shop on a stool at the end of a nurse’s counter in the neurosurgery ward. After several months, he was made a faculty member in the neurosurgery department and, by 1959, was given a joint appointment with the ophthalmology department, the first of its kind (Figure 4). Bill witnessed the human condition and understood how hard not only neurosurgical residents worked, but also the rest of the hospital staff. He understood how tired they could become doing the same tasks repetitively. By offering personalised attention to them whenever possible, examining their eyes or of their family members, offering a bottle of whiskey for a tired photographer who had gone the extra mile getting high-quality fundus images for him, or placing their names as co-authors on papers he wrote, Bill got the staff to see him not as another demanding boss or patron, but as a reciprocating friend.

Figure 4.

William F. Hoyt, MD, Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology and Neurosurgery, University of California, San Francisco, 1959. © 2002 Wolters Kluwer. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permissions.3

The payoff was enormous. Staff went out of their way to excel at what they did to get the best possible results for Bill. Fundus photographs, for example, were consistently of unsurpassed quality. “The ocular fundus in neurologic disease,” his 1966 3-D viewfinder atlas, with the reputation of being the most stolen book from any ophthalmic library, had UCSF ophthalmic photographer Diane Beeston listed as the co-author.2

When desiring neuro-radiological images, Bill, friends with the to-be-renowned and esteemed neuro-radiologist T. Hans Newton, who had also done prestigious fellowships in Europe, made sure to go down to the neuroradiology suite himself, and stand by the console with the technician performing the procedure to explain what exactly he was looking for, succeeding, to the amazement of his colleagues, in capturing lesions never before imaged. Gaining an understanding of his interests, his neuro-radiological colleagues would then sometimes alert him to their patients with concomitant ocular anomalies, such as Duane syndrome, that they thought he could be potentially be interested in, and would go out of their way to assist with having these imaged too.

Frank Walsh throughout this period kept promoting Bill, sending prospective fellowship candidates his way, and keeping him involved in the academic community at large. Bill’s first fellow, in 1961, and a favourite, was the multitalented Richard L. Sogg,2 later fond of referring to himself as being “Numero Uno.” Bill was not always so lucky with some other subsequent fellows, realising the lure of attractions in San Francisco might have been greater for them than working with him. So he thereby soon developed a formula to attract candidates more motivated to work hard and to learn, and which could also serve a dual, mutually beneficial purpose.

During fellowship selection, and before the fellowship began, he would try to jump-start their careers. He would write to the Chair of the prospective candidate’s residency program, that he could only take on their candidate if the Chair could guarantee them a faculty position upon completion of training. He found European chairs notably loath to give up any discretionary power, and the tactic did not always succeed, but in many instances it did. The knowledge of having an academic job waiting for the fellow upon their return home not only served as a “vouch” for the quality of the candidate from their own Chair, but also gave the fellow peace of mind to concentrate on their fellowship at hand rather than worry about future job prospects and hunting. It also, moreover, assured that the fellow paid close attention to everything Bill said, did, and taught because they would very shortly, right after the fellowship was over, have themselves to be able to teach others. What better way to motivate learning than by the prospect of immediately having to teach? As Bill explained, he did not necessarily require having the most knowledgeable fellow; what mattered most to him was that they be motivated, “That I can work with,” he said.

When, in 1963, Frank Walsh asked him to rewrite and co-author with him what would then be the third edition of the book Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology, after Lawton Smith had first declined to confront the enormous task, Bill accepted. They divided the task equally amongst themselves, devoting four intensive years to accomplish the feat (Figure 5). Completed in 1967, it only appeared two years later, in 1969, due to publishing house delays. The book was a milestone event in neuro-ophthalmology, with many new observations described, some of which, such as on orbital mucormycosis, still remain the most lucid descriptions on the subject today. Despite the enormous success of the book when it finally appeared, considered by some to be “Biblical” in its importance for the field, Bill nonetheless regretted the toll the hours devoted to the book had taken on his family life, and forever had misgivings about taking on the task. When, a little over a decade later, it came time to write a fourth edition, this time Bill declined Walsh’s invitation, and let Neil R. Miller update the book as a single author, over a 14-year period, with each updated volume appearing a few years after the other. Bill nonetheless still reviewed, made corrections and carefully proofread each volume, gradually tapering off his involvement. By the time the fifth and final volume covering infectious diseases was written, and after piling the enormous stacks of draft papers delivered in boxes to the conference room next to his office, he declared, “I won’t plan on reading that!” For the next, and 5th edition of what he called “The Book,” it had by then been decided in the interests of keeping all five volumes up to date, that it should now become a multi-authored textbook, with numerous chapters now being written by his previous fellows. Appearing in 1998, it took three years to put together, one year less than it had taken Walsh and Hoyt to accomplish together for the 3rd edition some thirty years earlier.

Figure 5.

William F. Hoyt and Frank B. Walsh meet at the Wilmer Eye Institute in 1967 upon completion of their textbook, Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, 3rd edition. © 2002 Wolters Kluwer. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permissions.3

Another break had come for Bill with the arrival of Charles B. Wilson then to head UCSF Neurosurgery in 1968, shortly after Wilson had spent a six-month sabbatical setting up a neurosurgical training unit in Ankara, Turkey (Wilson would leave once again, for a shorter period he considered to be a highlight of his career, to learn microsurgery from Gazi Yaşargil in Zurich).7 CW, as Bill would call him, particularly appreciated the value a neuro-ophthalmologist could add to a top-tier neuroscience department (Figure 6). As he would years later comment, “Dr. Hoyt was like a harpist. Every first-class orchestra needs just one, but not all of the time (Figure 7).”7 Coinciding with a special period in American medicine following the introduction of Medicare in 1965, which permitted vastly greater funding for academic institutions, and which continued unabated until Medicare reform began some twenty years later, the elements were all in place for a considerable and important build-up of the neurosciences at UCSF which greatly expanded Bill’s capacities, providing office space, secretarial support and even greater exposure to the neurosurgical service in which Bill would now be a fully salaried member. Bill Hoyt appreciated these extraordinary circumstances with the full support of such a remarkable Chair in an expanding department where a “critical mass” had now been achieved. Bill Hoyt and T. Hans Newton had already established successful weekly grand rounds discussing the imaging and clinical details of unusual cases. When they invited CW to participate and discuss the surgical aspects of cases, the rounds became legendary, with the auditorium filled to standing room only capacity with videotapes sold by subscription worldwide.7

Figure 6.

Bill Hoyt with UCSF neurosurgeon Charlie Wilson, “CW”. © University of California, San Francisco. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 7.

Harpist as a metaphor for neuro-ophthalmologists, “Every first-class orchestra needs just one, but not all of the time” said Neurosurgery chief, Charlie Wilson.

Despite any personal misgivings about the intensive effort required writing the book, its ramifications and positive effect on his academic career was not to be disputed. Bill Hoyt became the paragon of neuro-ophthalmology on the West Coast, while Lawton Smith, at the growing Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, became its student on the East Coast.3 The friendly nature of their competition brought out the best in each. Frank Walsh’s nature towards his fellows had been avuncular, and Lawton Smith and Bill Hoyt each had their own approaches. For Bill, it was, as former fellow Jack B. Selhorst would describe, the most exacting and demanding, but at the same time one of the most enthusiastic and nurturing mentorships of all time (Figure 8). A particularly apt quote from Shakespeare used by fellow Barrett J. Katz to describe him was:3

Figure 8.

John B. Selhorst, MD, (left) and Neil R. Miller, MD, (centre) during their fellowship year, with Hoyt (right), 1975. © 2002 Wolters Kluwer. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permissions.3

A scholar, and a ripe and good one;

Exceeding wise, fair-spoken, and persuading:

Lofty and sour to them that lov’d him not;

But to those men that sought him sweet as summer.

Shakespeare, King Henry VIII

As Bill Hoyt would say of Frank Walsh, many would also say of Bill; they had never learned so much from one person in one year. The success of “The Book” and Frank Walsh’s blessing with CW’s support meant Bill could begin to draw some of the most talented people from around the world to do fellowships with him, despite some changes in immigration laws than began appearing in the mid-1970s inhibiting the arrival of foreign-trained talent.3 For some, such as Gordon T. Plant from England, they might already be so knowledgeable prior to their arrival, that Bill could sometimes wonder what more they could benefit from another year of training. Reckoning Gordon Plant to be the most knowledgeable person in the field still now, there was, nonetheless invariably always more to discover. As Plant recently stated, there was so much he learned from Bill and that he has been so grateful for. Bill Hoyt always believed learning to be a two-way street making use of the opportunities to teach his fellows, as well as to learn from them, with his knowledge base constantly changing and expanding. Once a lecture or presentation was prepared and given, he rarely repeated it again, working instead on something new thereafter.

Typically, only between two and five patients would be seen in an extended morning session. Each patient, referrals only, would also have to receive Bill’s personal approval in order to be scheduled. Such approval would come about based on the teaching value he felt the case would have for his fellows. Hence, if it was obvious the patient had a carotid-cavernous fistula, and two patients with carotid-cavernous fistulas had already been seen by the fellows in training, he would decline to accept a third, explaining to the referring physician over the phone that the fellows had already learned what there was to learn from the first two, and no longer needed now to see any more. It was truly the model for, and eventually, following changes in healthcare reimbursement, the last of the true “teaching fellowships.” Into the 1980s, fellows and residents were also expected to see neurosurgical patients admitted on the eve of their surgery, and to report to Bill on their pathology, calling him at home in the evening for all to be able to prepare for a discussion with relevant literature the following morning. But following the advent of neuroimaging, Bill would later admit that the yield from seeing such patients was no longer worth quite the time devoted to it, and when changes in health insurance coverage forced same-day admittance for surgery precluding such pre-operative assessments, they were not greatly missed.

Always wishing to put patients at ease, he openly admired the capacity of others, notably William V. Good, a child psychiatrist before going into ophthalmology, to do so. Bill was also always conscious of patients’ time and avoided having them spend excessive periods in the clinic.

Even when there was nothing one could do for their loss of vision, he placed special emphasis on letting patients know if there was no other danger lurking behind. Unvoiced patient fears of ophthalmological problems being caused by brain tumours were directly addressed and dispelled, usually producing audible sighs of relief from patients, as he would point out to students and fellows. “If I can’t help their disease, at least what we can do is take away some of the fears they have associated with it,” he would emphasise.

Rather than go through an exhaustive “textbook flowchart” admixing common possibilities with the remote and ordering numerous tests, his laser focus on the problem that brought the patient in made him a favourite with patients, and taught residents and fellows how to hone in more efficiently and effectively on a problem. He indeed taught the expert approach to patient care, and to look beyond what was immediately in front of you, much as would a real-life Sherlock Holmes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the ophthalmologist and creator of the fictional detective, had studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and modelled his protagonist on his professor, Dr. Joseph Bell (related to Sir Charles Bell, of Bell’s palsy, Bell’s phenomenon, and other eponymous discoveries), who had emphasised in his teaching the importance of observation, deduction and evidence.8 “When a patient is referred to you for slow, progressive visual loss of unknown aetiology, after having been seen by a general ophthalmologist, a retina specialist, and then a neurologist, even before the patient had arrived in the office, the first thing to think of would be an oil droplet, a.k.a “invisible” cataract, of course,” Bill would say. Such cataracts are not due to scattering elements within the lens, but to inhomogeneities in refractive power developing over time, go unnoticed on a slit-lamp examination. A simple glance with a retinoscope or at the fundus through the target mires of a direct ophthalmoscope, would attest to the optical aberrations causing blurred vision. “If it were anything else, the other folks would have picked it up!” he would explain. Similarly, astute observations were made about amaurosis fugax, and many other entities. “When a patient is referred to a neuro-ophthalmologist for amfu, you can bet they don’t have any of the problems listed in the textbooks as potential causes, because they would have found them and not referred them to you in the first place. Since the vast majority of cases of amaurosis fugax are not traceable to any cause, including cardiovascular disease, simply letting the patient know that can give them back their life. Otherwise, they’ll go home thinking they have occlusive disease no one has been able to localise and will just be waiting for the axe to fall.”

Bill liked to direct himself to questions in the field. He was not so interested in pat answers to things as described in textbooks, but wanted everyone to query, and use mechanisms of disease, to understand what was going on. The Socratic method of teaching via questioning was not aimed at students and fellows alone, but for all. He was not just interested in what was already answered, but curious about what was unknown and questioned conventional belief.

His fellows worked at a large table in his office, rather than in isolation. “I enjoyed this kind of community relationship with the young doctors, where conversations and questions were always open. I lived in a fish bowl, but I enjoyed it,” said Hoyt.3 He enjoyed the camaraderie of colleagues and when once asked how to choose between competing job offers and work environments, his advice was to “Go to where the fellows are; we feed off of them.”

Despite the questioning that could occasionally be intimidating for some fellows (he later admitted having been too tough), Bill made them eventually feel more comfortable with the field itself, showing one should not be overawed by masses of facts and answers some felt the need to memorise, but to think about the mechanisms of disease and the science instead for which there are yet so many unanswered questions. Knowing what questions to ask, and how to use the literature to find the answers, would cause fellows to embrace the field further. Showing how there is even a positive side for the patient in making diagnoses of diseases without cure, by reducing their associated fear. Indeed, why so many of his fellows went on to illustrious careers was that they did not see neuro-ophthalmology as some laborious and time-consuming field with inordinate tests to order to “cover all bases,” but they learned to order tests with a courage instilled to trust their own reasoning. That made his fellows enjoy the clinical practice as well as the field, and would help assure a patient even nearly blinded by bilateral apparent non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, relieved, in some not insignificant measure, that it was not a harbinger of a stroke or cardiac arrest.

Similarly, when it came to interventions, his observations on various topics, such as considering juvenile optic gliomas to behave as hamartomatous growths, caused him to take principled stands for conservative treatment, using rationality and logic, rather than emotional responses or beliefs which pushed others to intervene with unproven therapies that might do more harm than good. Maintaining such unpopular stands won him the admiration and respect of many, including Charlie Wilson, and the everlasting ire of those promoting radiation and other therapies, in spite of the evidence emerging over the decades. There simply was no room for superstition, no room for authoritative “beliefs” in Bill Hoyt’s world. Everything had to be based on facts and reason.

He spent a great deal of time teaching fellows how to write scientific reports. Write them, he would say, for those who should be reading them; do not “dumb them down” for a broader audience who could not appreciate the significance of what is being discussed anyway. Be concise and precise. To keep your papers from becoming dated, try as Cogan did, to avoid speculation. As Robert B. Daroff, his first neurology-trained fellow (spurring Lawton Smith to immediately agree then to take on neurology-trained Norman J. Schatz as a fellow too, creating a new path for other neurologists to follow) would later admonish as Editor-in-Chief of the journal Neurology, “first have something to say, say it, and then stop!”

His clinic notes, were similarly short and to the point. As he, and Joel S. Glaser both well appreciated, neurosurgeons had little time or patience to read long notes (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Visiting with Joel S. Glaser, MD (right), a former fellow and medical student, in 1976 at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, Florida. © 2002 Wolters Kluwer. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permissions.3

While most of what we learn is via vision, by seeing patients and via reading, Bill Hoyt had a knack for making aural impressions as well. Carefully chosen words, aimed right at the heart of the matter, forcefully enunciated could long, if not forever, linger in the recipient’s mind. If a fellow asked a “foolish” question, Bill could sometimes respond with a forceful tirade. His real intent, occasionally belied moments later when he might softly add, “Did I emote enough?”, revealed how he really wished to train fellows to think before speaking. One never forgot what Bill said, in addition to what was read, and that was another avenue for learning. As remarked by Jack Selhorst, however, that without a larger audience to impress the point upon, Bill was always softer when alone with a trainee.

Making world-class contributions and drawing world-class fellows from the four corners of the world, Bill had hit full stride (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10.

Bill on the Sausalito side of the Golden Gate Bridge overlooking his “biosphere.”

Figure 11.

Thomas J. Carlow, Joel Glaser, Bill Hoyt, Robert Daroff, Norman Schatz, founders of the North American Neuro-ophthalmology Society in 1976 (originally called the Rocky Mountain Neuro-ophthalmology Society/Ski Club), in 1993. © 1996 American Academy of Ophthalmology, Inc. Published by Elsevier. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.2

Moving with the times to redirect the future

T. Hans Newton had seen the very first EMI scan in London in the late 1960s and by the time Creig S. Hoyt, previously trained in neurology and now finishing his UCSF training in ophthalmology, came into Bill’s office in 1975 to discuss an anticipated fellowship year with him, Bill was looking at, and showed him, some of the newer CAT scans, as they were just now being called (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The internationally trained trio; T. Hans Newton, MD, UCSF neuroradiologist (left), and Charles B. Wilson, MD, UCSF chair of neurosurgery (centre), with Hoyt at Dr. Wilson’s retirement gala, 1994. © 2002 Wolters Kluwer. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permissions.3

Bill had grasped that a major reason for the utility of neuro-ophthalmologists in neurosurgical units would henceforth diminish. “This machine has taken away the anatomy from our field,” he said, “but it won’t take away physiology.”

As another prominent fellow and associate, Jonathan C. Horton (Figure 13), would remark years later, the superior resolution afforded by the ophthalmoscope over neuro-imaging for the optic nerve head and for the retinal nerve fibre layer that Bill had done so much work to map out, still assured an ongoing role for classical neuro-ophthalmology, but a paradigm shift had nonetheless occurred. Bill, hence, began actively promoting additional training for Creig Hoyt with pioneers in paediatric neuro-ophthalmology such as Frank A. Billson at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne. A greater number of such dual-trained, paediatric ophthalmology, as well as neuro-ophthalmology-trained individuals, beginning in the 1970s, went on to establish prominent academic careers as paediatric-neuro-ophthalmologists, or as Bill would sometimes describe, developmental neuro-ophthalmologists. These included, amongst others, notables such as J. Raymond Buncic and Barry Skarf at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Creig Hoyt and Bill Good at the University of California, San Francisco, David S. I. Taylor and Nicola K. Ragge at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, and Michael C. Brodsky now at the Mayo Clinic, with several reference textbooks authored amongst them.

Figure 13.

Bill with former fellow and UCSF associate, Jonathan Horton and wife Lydia, circa 1995.

Though he had such a hand in shaping its future direction, Bill was also wise enough not to venture to say where neuro-ophthalmology would go in the next 20 or 30 years. He had already been witness to how neuroimaging, for example, had already changed things once so unexpectedly.3 And so, much as the physicist Richard P. Feynman explained when asked to predict the future of fundamental physics,9 one could at least recognise that the field clearly would not disappear. How could it when the brain itself represents an outgrowth of the eye?10 But its course, including its pace, was already rapidly changing. Physicians and neuroscientists interested in visual and ocular motor physiology would certainly continue to develop, and there would be contributions from many directions, but most of which we could never predict.3

It was exactly because of this continual adapting to changing circumstances, learning from, as well as teaching, fellows, and writing original manuscripts with them, that one could never “run dry” during a period spent with Bill. As Creig Hoyt (not a relative, though one of his closest friends and associates) said, “with most fellowships you learn a finite amount of what there is to learn from the mentor in about a year or so. But with Bill it is different; as long as you are there with him, you are still learning.” Michael Brodsky would also say, “the amazing thing about doing a fellowship with Bill is not just all that you learn during the fellowship, which is enormous, but all that he does for you and continues to teach you after the year is over.” Bill would follow the careers of his former fellows, their publications, send them pertinent articles as well as ideas he thought would further their research, or help to develop them, make introductions to others in the field he thought they could collaborate with, and would come to lecture at their home institutions to “vouch” for and support them in their community.

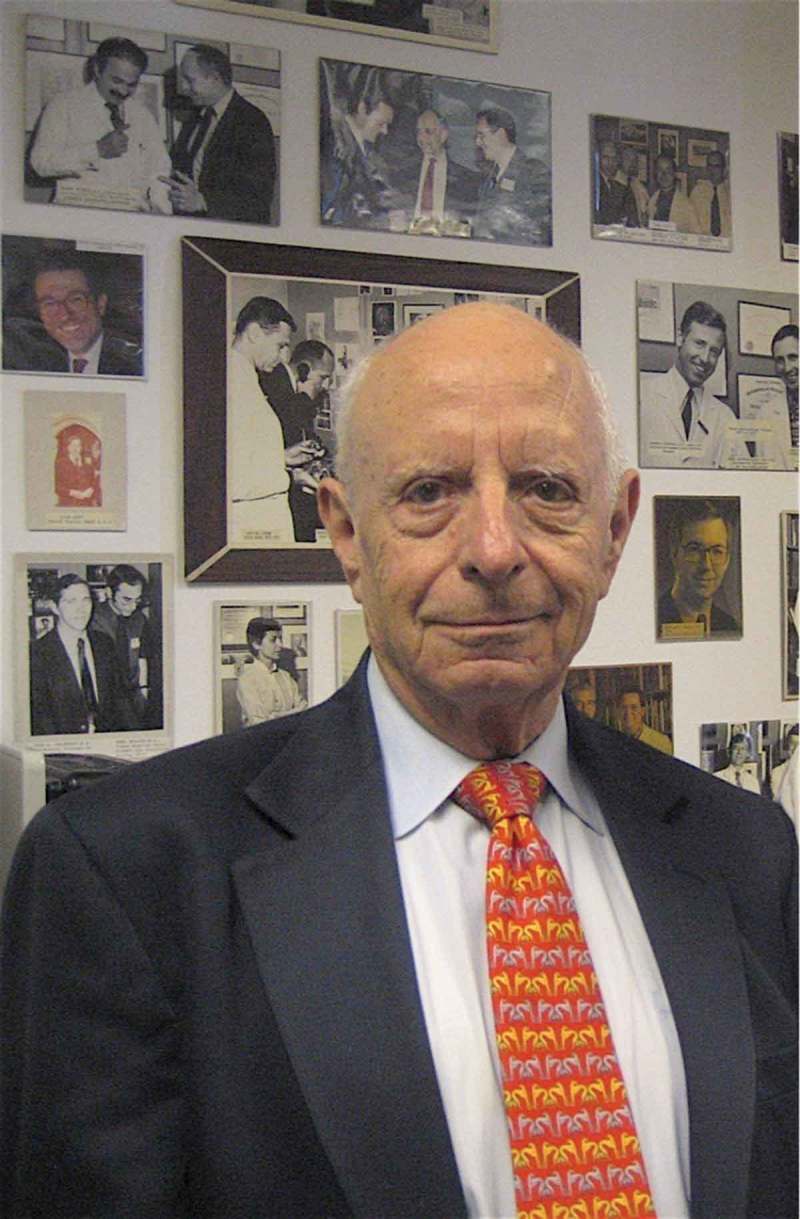

In later years, prospective fellowship candidates interviewing could sometimes be intimidated by the growing number of photos mounted on “The Wall” in his office displaying former fellows having become luminaries in the field. One candidate, when tendered the offer of a fellowship right in the office, thought perhaps best to immediately forewarn Dr. Hoyt that he might not be up to the same level of some of those whose pictures he saw displayed. Bill laughed heartily and reassured him, “they weren’t luminaries when started here, the year in fellowship is merely the start of a process which then goes on if you want it to (Figure 14).”

Figure 14.

Bill with Jenny Hsiao, longtime secretary 1978-2005, circa 1995.

Much like Walsh, his mentor, Bill kept an open door policy. Former fellows back in town for whatever reason were always welcome, and routinely stopped by his office to meet and engage with others in training, sharing cases and points of discussion. He thrived on such camaraderie.

As did Richard K. Imes, a fellow in 1983 along with Mario L.R. Monteiro from Brazil, and who thereafter stayed to practise in the Bay Area and teach at the California Pacific Medical Center. He continued to come by Bill’s office every Monday until Bill’s full retirement, thereafter periodically visiting Bill at his home, sharing and discussing interesting cases, as well as writing manuscripts, a de facto member of the teaching programme appreciated by residents and fellows alike.

As already stated, Bill trained 72 full-year fellows, with countless more who came for shorter periods.3 Some stayed longer or did multiple fellowships if they could. Raphael Muci-Mendoza, an internist with developed expertise in ophthalmology from Venezuela, came with his family to spend two years in training with Bill. He and his wife, Graciela, not only became some of his closest friends (Figure 15), but Muci, as he goes by, returned to Caracas to create the premier neuro-ophthalmic training program for all of South America. “The placement of one really well educated neuro-ophthalmologist in a country like Venezuela was a bigger accomplishment for me than placing ten people in the United States” Bill would later remark.3

Figure 15.

With former two-year fellow, Raphael Muci-Mendoza and his wife Graciela, 1995.

Bill often enjoyed recounting stories and accomplishments of his former fellows and contemporaries, teaching as well as building a sense of community and forging links amongst his former fellows as well as with others in the field. He built a sense of fraternity amongst neuro-ophthalmologists, introducing them to each other at every opportunity. Whereas as Arthur J. Jampolsky states, in the field of strabismus there seems to be, beyond schools of thought, even distinct “cults” amongst surgeons, the lack of procedures and the paucity of fiscal rewards in neuro-ophthalmology, along with Bill’s consistent personal efforts to harmonise relations created a sense of community towards a grander goal of scientific knowledge for its own sake (Figure 16). At the NANOS meetings, one sensed an integrated consciousness of the field, with cohesiveness even amongst rivals that gave it a welcoming atmosphere.

Figure 16.

70th year Festschrift celebration at UCSF. A gathering of former fellows at “An update in Neuro-ophthalmology” held in San Francisco in 1995. (Hoyt in front row, to the left of Thomas R. Hedges III and Richard Sogg). © University of California, San Francisco. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

To Bill, scientific truth knew no borders and he travelled widely to spread knowledge, interested in all the world, whether countries formerly considered enemies during WWII, learning Russian while there was still an Iron Curtain (discreetly, and admittedly without great success), and visiting the so-called “axis of evil” to promote neuro-ophthalmology and former fellows teaching there. Culturally open-minded, even when he could have opposite views, he believed in having others freely voice their opinions. As a US-trained neurosurgeon based in Tehran, witnessing how tolerant Bill was listening and allowing others to voice opinions so different from his own during private group discussions, afterwards remarked, “Bill Hoyt is a democratic person in the truest sense of the word (Figure 17 and 18).”

Figure 17.

A gathering of participants at the 16th INOS meeting, Tokyo, 2006. Bill standing in front centre, with Thomas R. Hedges Jr. to his left.

Figure 18.

Summit meeting. With former fellows, David Taylor (England), Mostafa Soltan Sanjari (Iran), Creig Hoyt (USA), and Irina V. Rubtsova (Russia) during a second “axis of evil” Tehran conference visit for the Iranian Society of Ophthalmology, 2008.

Bill Hoyt aptly picked the kangaroo to be the “mascot” of his fellowship, with a kangaroo emblem tie awarded at completion of a fellowship period. As he would explain, kangaroos are of little commercial value, but are fun to have around. It remains now the logo for his collection of slides, carefully culled and categorized, freely available for all others to use on the Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library (NOVEL) website.

People were rightly amazed at his fund of knowledge as well as his ability to recollect pertinent literature at conferences, holding up speakers to the highest standards of scholarship (much as the great ophthalmic pathologist, W. Richard Green would also famously do). This ability was not merely the result of having a good memory (“a steel trap,” as UCSF resident Stephen Stechschulte commented), but as he stated, the result of active efforts. Much as he had asked of his fellows after seeing neurosurgical patients admitted on the eve of their surgery, to call and let him know of the diagnoses so he could read-up and consult his collection of references on the topics to be discussed before morning rounds, Bill would do much the same before a conference meeting, looking up the topics scheduled to be presented and consulting his collection of carefully filed and numbered references. If a speaker failed to mention an important piece of work, Bill was then ready to point it out. He was also unafraid to point out inconsistencies; as he called out to a presenter at a Walsh meeting, proud to have obtained the first biopsy of a lesion only he had understood and already had had experience with before. “Well, if you were the only person in the world to know what it was, why did you then biopsy it?”, he asked. As Jack S. Kennerdell then openly marvelled, Bill Hoyt always had an uncanny ability, with laser-sharp focus, to cut through an argument with a well-placed question to keep the science honest and on track.

Yet, it had been rather abrupt, after his 65th birthday, that he began pulling back from making such comments or interjections at meetings, with only a handful of exceptions, even when solicited. He had decided to purposefully retract himself, feeling it was the right time and right thing to do, in order to help allow younger generations to grow outside of his shadow and without worry of being intimidated. Unlike many who achieve levels of fame, Bill did not have a fear of being seen as diminished and was always himself, never putting up appearances. Despite his ongoing full-time practice with consultations, fellowship and resident training, and manuscript preparation, he would henceforth focus on invited presentations to help support his protégés.

Bill Hoyt did not see himself as just a single, isolated person, but as part of an integrated group with his fellows, carefully selected, groomed and supported, and interacting with others, that multiplied and propagated advancements in the field (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Bill in his UCSF Parnassus Street office in front of “The Wall” where photographs of many fellows, particularly following great achievements, were posted, circa 2007.

Retirement of Jenny Hsiao and end of consultation practice in 2005

Bill had previously declared that he would end his consultation practice whenever his longtime secretarial assistant, Jenny Hsiao would retire. Following 32 years of thoughtful and loyal service to the neurosurgery department, 27 years of which as Dr. Hoyt’s assistant, her own stated intention was to retire early, at a very youthful 55 years of age. Her plans, with her daughter by then in college, were to go and travel the world with her husband, living part-time in her homeland of Taiwan, as well as in China and in San Francisco. Hence, in 2005, Bill Hoyt ended his patient consultation practice. Tragically, however, Jenny was found to have an unexpected terminal disease on a routine physical examination. Her untimely passing three years thence deeply affected Bill. Generally stoic and unsentimental, he was surprised at his own devastation, experiencing difficulty adjusting to an office without patients, and the knowledge that the otherwise ever-present and lovely Jenny was no longer of this world.

He continued teaching, nonetheless. He still came into the office daily to teach residents, attend rounds, and, twice per week, would oversee patients with Timothy J. McCulley and his fellow in a practice that began in 2006, continuing until McCulley left UCSF for Wilmer in 2010. As Tim McCulley stated, he was so grateful that Bill would sometimes pull him aside and, ever so gently and diplomatically, mention the possibility of an overlooked diagnosis in the differential. Bill continued also to make novel observations, such as enophthalmos occurring from excessive CSF shunting (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

INOS 2010 attendees in Lyon, France. The evening was capped off by a celebration for William F. Hoyt in the Chapelle de la Trinité, with an operatic performance followed by whispered Happy Birthday wishes from soprano and former ballerina, Mademoiselle Laurence Janot. Former fellow Klara Landau seated to the left of Bill Hoyt (seen from back). David S. Zee seen in foreground, with Lanning Kline in background both to the left.

Finally, he decided then to develop and elaborate upon thoughts on what had persisted, along with juvenile optic gliomas, to be the most enigmatic pathology in clinical neuro-ophthalmology.

He would tackle one last puzzle.

He would propose a hypothesis, based on all the available objective evidence, much like he had done with his medical student Harald Nachtigäller many years before, and against the prevailing wisdom of the time. Which had then been to propose, for the first time in medicine, how paradoxical innervation of organs was a possibility, and could explain all features of the then-enigmatic Duane retraction syndrome. It would be left for others, appropriately directed, as Neil Miller had been once before, to obtain confirmatory proof.

Much as his landmark 1969, 1986 and 2001 studies on so-called juvenile optic “gliomas,” the most common brain tumour of childhood, with his work nonetheless still disputed by traditionalists today, he would now directly question underlying assumptions about so-called non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, the most commonly occurring acute optic neuropathy in older adults. He considered the appellation of both entities to have been misnomers blocking clear thinking and to have inhibited progress.

While initially proposing notions of vitreo-papillary separation as potentially causative in 1978, he had intensified his work on the subject, especially since the 1994 San Francisco symposium given in his honour at the American Academy of Ophthalmology on the subject of amaurosis fugax, another entity which he also suspected was due to vitreous separation, causing ephaptic retinal depolarisation. In cooperation with various former fellows, and then with the availability of clinical OCT, he further developed his thoughts on the matter. A manuscript draft was prepared in 2010, but continued bibliographic searches occurred and available evidence was scrutinised to refine the discussion until submission in 2014. Several rounds of peer-review (including by two former fellows, one in favour of, and the other opposed to the hypothesis) ensued. When later asked if he thought anyone could, simply from reading the paper, ever realise how many years of work had gone into producing the short two-page editorial questioning if any true ischaemia existed in this so-called ischaemic disease, he paused, with then a succinct “no.” He anticipated disapproval from Sohan Singh Hayreh with a characteristically simple reply: “The authors stand by their comments.”

He attended his last NANOS meeting in 2015, in San Diego, where the work was first presented. It had also been announced there that he was the oldest attendee, which generated mixed feelings in him. “I don’t know if it is a good thing,” he said.

He continued driving in to his office to occasionally teach residents while corresponding with former fellows via email until late 2015, when he decided then to fully retire from teaching (Figure 21). His memory had begun to fade, akin now to the Sherlock Holmes portrayed by Sir Ian McKellen in the movie entitled “Mr. Holmes” he had just seen that summer.11 In real life, however, Bill Hoyt had accomplished even greater feats than the fictionalised hero. If, as some believe, making general scientific discoveries could be considered the epitome of uncovering truth,9 Bill Hoyt’s contributions to his field, and his nurturing of others to continue doing so, were of a greater order.

Figure 21.

Bill with former fellow, weekly fellowship training participant, and loyal friend, Richard Imes in his UCSF Parnassus street office in 2015. On the left are photographs of former fellows posted on “The Wall.”

When reality surpasses imagination, life becomes art.

More than anyone else, Bill Hoyt had been able to define the field of neuro-ophthalmology. For over six decades in a subspecialty hardly 80 years in existence, from collaborating with its modern founder, Frank B. Walsh to establish the reference textbook defining the field, to co-founding the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society (NANOS), to recognising the impact of neuroimagery and redirecting the field yet again, focusing on developmental problems and identifying errors in thinking, Bill shaped the field as no one else had, or could ever again do. For as Richard Feynman also stated about living in heroic periods, you cannot discover America twice.9 Bill Hoyt was witness to, and participant in, the Golden Age of our field and represented the acme of its members during this period.1

He came at the right time with the right background to define a field as few ever have the opportunity to do. Open-mindedness, logic, honesty and confidence, characteristics of the Bay area at the time were some key elements. He did not let ego, fear or tradition get in his way. He understood how one could achieve more by giving, rather than taking, from one’s fellows (Figure 22 and 23). As he told his former fellow, Walter M. Jay, he was more proud of his fellows than he was of his book. An academician in the purest sense, having the freedom to pick projects of greatest interest to him, these hence often bore the greatest fruit. Nonetheless, these qualities, he well understood, would not suffice under today’s circumstances.

Figure 22.

Old friends Dick Sogg and Bill Hoyt, in his Sausalito house, March 2016.

Figure 23.

Selfie of Bill Hoyt in his house with his first and last full-year fellows, “Numero Uno” Dick Sogg, and “Numero Ultimo,” Cameron Parsa during a post-NANOS 2016 visit.

Medicare reform had eventually eliminated the support for academic medicine that had so benefited Bill and his colleagues. Also expressed by contemporary Simmons Lessell12 and chronicled by the physician and professor of history, Kenneth M. Ludmerer, in his book, Time to Heal,13 Bill Hoyt often stated that with all the pressures to generate revenue today, he would have never been able to achieve what he did before. He shook his head at the pressures younger physicians now have to endure. Because, in an age of administrative control where quantity holds priority over quality, the circumstances simply are no longer there to permit another to grow into an academician of similar calibre. Bill was eternally grateful for the opportunity given to him to thrive, with the goal set for excellence above all.

His work, hence, continues to define the field. Based on the model for modern academic medicine created by Osler, Halsted, Welch and Kelly at Johns Hopkins in the late 19th and early 20th century, creating and emphasising the role of the clinician-scientist, Bill Hoyt, Charlie Wilson and T. Hans Newton with their colleagues at UCSF, took full advantage of the possibilities available during the funding peak for university-based academic medicine in America’s post-war Golden Age, propelling modern clinical neuroscience to an apogee. Their many fellows throughout the globe continue the pursuit.

Despite the lack of funding support and fiscal rewards and the fewer fellowships now being offered in the United States, more and more ophthalmologists, nonetheless, are calling themselves neuro-ophthalmologists, while the membership of NANOS keeps growing. Simply, this is because the need and desire for such subspecialists persists.

Akin to other currently non-remunerative subspecialties such as ophthalmic pathology, we may have to await changes that will once again support academic medicine and usher in a new Golden Age with a critical mass of individuals to help drive one another, causing the field to blossom in new directions.

While Bill Hoyt stayed on the sidelines these last decades to better allow for others to take over the mantle, with the fewer opportunities available today for academic reflection and where conclusive evidence was not yet available, some chose to distinguish themselves by promoting views opposed to his. However, as one former editor of the Archives of Ophthalmology, Morton F. Goldberg, likes to point out, the ultimate testimony for the validity of scientific work is withstanding the test of time; as is generally noted, rational views supported by accumulated evidence tend to win over those based on other needs. Bill Hoyt’s consistent scientific integrity when taking positions led many to label him the ultimate clinician-scientist in the field.1

Upon learning of Charlie Wilson’s passing last year, Bill became deeply affected, becoming acutely aware of Charlie Wilson’s age, and then his own, reflecting upon CW having now passed away, as had already T. Hans Newton (Figure 24). He spoke about how much history he had had together with Charlie. He also mentioned how lucky he had been to practise at the time in history that he had, to have had the support he did from Charlie and others to be independent, and how he had appreciated it all. He remarked how wonderful it had been to have colleagues like T. Hans Newton to collaborate with. He attributed it to luck. But then, as so ever always the case, with piercing insight so directly stated, he also added “but I did make the most out of it.”

Figure 24.

At home with son, Kristian, March 2018.

Some months later, during my last visit with Bill, at the time of Arthur J. Jampolsky’s centenary celebration and fellows’ reunion, after discussing respective periods working in Baltimore, I asked him what he considered his best career decision. Without missing a beat, he answered that it had been to have not taken Ed Maumenee up on his offer to replace Frank Walsh at Wilmer and to have stayed right where he was in San Francisco, in his own “biosphere,” as he put it (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Bill Hoyt in his home decorated with Japanese art, 2018. Some of his numbered reference files can also be seen in recessed background office.

Rational and humanist, a product of the Bay Area, seeing the fog lift from the Sunset District visible from his office window every day, still sand dunes in his mother’s memories, the old admonition to “go west, young man, go west” in the New World had proven still so apt and true.

He was proud when told that his work had withstood the test of time. When assured it was something that he should not have to worry about, he asked why. “Because it was always honest.” To which a broad smile came across his face.

He lived at his home until this year, with daily visits from his son and family. Contributing his body to UCSF science, he is survived by his sister, Peggy, his son Kristian F. Hoyt, daughter Erika Milano, former wife Johanna and longtime partner, Ursula Gropper.

The things Bill said were important in life were love from your family, and respect from your colleagues.

Insofar as it can be ascertained, the degree of respect his colleagues had for him was unparalleled, with many of those feeling to have also been a part of his family.

References

- 1.Karanjia R, Sadun AA.. The foundation of neuro-ophthalmology in the United States of America. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(3):447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson HS. The growth of American neuro-ophthalmology in the 20th Century. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(Suppl.8):S51–65. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kline LB. An interview with William F. Hoyt, MD. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2002;22(1):40–50. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser JS. The golden age of neuro-ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2002;22(3):222–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrary JA. An update in neuro-ophthalmology (in honor of William F. Hoyt, M.D.). Neuro-Ophthalmol. 1987;7(2):65–68. doi: 10.3109/01658108709007431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kommerell G. William F. Hoyt , seminal for neuro-ophthalmology in Europe: Laudation given at the meeting of the European Neuro-Ophthalmological Society, Tübingen, 22–26 July 2001. Neuro-Ophthalmology, 27 (1-3):9-11, 2002. doi: 10.1076/noph.27.1.9.14305. [DOI]

- 7.Andrews BT. Cherokee Neurosurgeon. A biography of Charles Byron Wilson, M.D., CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Scotts Valley, Ca, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osborn J. Observation, Sherlock Holmes, and evidence based medicine. Med Secoli. 2002;14:515–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feynman RP. The future of physics. As published in the technology review, 1961–1962. Extracted from “Perfectly reasonable derivations from the beaten track: the letters of Feynman” (Basic Books, 2005), Appendix III. Reprinted in: Yang CN. The future of physics revisited. Int J Mod Phys A. 2015;30:1530049–1–1530049–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwab IR, Sadun AA . An out-pouching of the eye? Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 Sep;91(9):1107-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Mr. Holmes (2015), directed by Bill Condon, starring Sir Ian McKellen as retired Sherlock Holmes. Based on novel by Mitch Cullin, screenplay by Jeffrey Hatcher, created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, M.D.

- 12.Trobe JD. Simmons Lessell: The gaon of neuro-ophthalmology. J. Neuro-Opthalmol. 2007;27(1):61–73. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3180321593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludmerer KM. Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care. New York: Oxford University Press; Revised ed. edition January 27, 2005. [Google Scholar]