Abstract

Background:

Investigations of drinking behavior across military deployment cycles are scarce, and few prospective studies have examined risk factors for post-deployment alcohol misuse.

Methods:

Prevalence of alcohol misuse was estimated among 4,645 U.S. Army soldiers who participated in a longitudinal survey. Assessment occurred 1–2 months before soldiers deployed to Afghanistan in 2012 (T0), upon their return to the U.S. (T1), 3 months later (T2), and 9 months later (T3). Weights-adjusted logistic regression was used to evaluate associations of hypothesized risk factors with post-deployment incidence and persistence of heavy drinking (consuming 5+ alcoholic drinks at least 1–2×/week) and Alcohol or Substance Use Disorder (AUD/SUD).

Results:

Prevalence of past-month heavy drinking at T0, T2, and T3 was 23.3% (SE=0.7%), 26.1% (SE=0.8%), and 22.3% (SE=0.7%); corresponding estimates for any binge drinking were 52.5% (SE=1.0%), 52.5% (SE=1.0%), and 41.3% (SE=0.9%). Greater personal life stress during deployment (e.g., relationship, family, or financial problems) – but not combat stress – was associated with new onset of heavy drinking at T2 [per standard score increase: AOR=1.20, 95% CI 1.06–1.35, p=.003]; incidence of AUD/SUD at T2 (AOR=1.54, 95% CI 1.25–1.89, p<.0005); and persistence of AUD/SUD at T2 and T3 (AOR=1.30, 95% CI 1.08–1.56, p=.005). Any binge drinking pre-deployment was associated with post-deployment onset of HD (AOR=3.21, 95% CI 2.57–4.02, p<.0005) and AUD/SUD (AOR=1.85, 95% CI 1.27–2.70, p=.001).

Conclusions:

Alcohol misuse is common during the months preceding and following deployment. Timely intervention aimed at alleviating/managing personal stressors or curbing risky drinking might reduce risk of alcohol-related problems post-deployment.

Introduction

The burden of alcohol misuse on our nation’s public health (Grant et al., 2015, Okoro et al., 2004, Sacks et al., 2015) extends to the U.S. Armed Forces, where hazardous drinking poses threats to both the health of individual servicemembers and troop readiness (Bray et al., 2013, Hurt, 2015). Military personnel who drink heavily suffer more accidents/injuries; occupational, relational, and legal problems; and productivity loss than others (Mattiko et al., 2011). Moreover, alcohol misuse is associated with mental disorders (Sampson et al., 2015, Stein et al., 2017), suicidal ideation (Mash et al., 2014), and suicide (LeardMann et al., 2013) among servicemembers. Improved understanding of scope and risk factors may help reduce alcohol misuse and its sequelae within the military population.

Deployment to a combat zone increases risk of alcohol misuse among certain subgroups (Jacobson et al., 2008). Yet systematic characterizations of drinking behavior across military deployment cycles are scarce (Harbertson et al., 2016, Hurt, 2015); and few prospective studies have investigated risk factors for post-deployment alcohol misuse. A notable exception from the Millennium Cohort Study examined alcohol misuse among >48,000 previously non-deployed U.S. servicemembers surveyed in 2001–2003 and 2004–2006 (Jacobson et al., 2008). Deployment with combat exposure during the time between surveys was associated with onset of binge drinking among active-duty personnel; and with onset of binge drinking, heavy drinking, and alcohol-related problems among Reserve/National Guard personnel. Risks were not elevated among personnel who were deployed but not exposed to combat.

Non-combat-related stress also may contribute to risk for alcohol misuse. Independent of combat stress exposure, personal life stressors were associated with subsequent Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) among Ohio National Guard members who had deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan (Cerda et al., 2014). Similarly, changes in alcohol consumption were associated with personal life events but not deployment to Iraq/Afghanistan among UK military personnel (Thandi et al., 2015). Vulnerability to post-deployment alcohol misuse also may depend on socio-demographic and military service characteristics (Boulos and Zamorski, 2016, Jacobson et al., 2008) or mental health factors such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD), which are consistently linked to alcohol misuse in military samples (Jacobson et al., 2008, Kehle et al., 2012, Thandi et al., 2015, Thomas et al., 2010, Stein et al., 2017).

The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Pre/Post Deployment Study (Kessler et al., 2013a, Ursano et al., 2014) affords opportunities to examine drinking behavior across the deployment cycle and prospective risk factors for post-deployment alcohol misuse. We estimated prevalence of binge drinking, heavy drinking, and alcohol or substance use disorder (AUD/SUD) among soldiers shortly before their deployment to Afghanistan, and approximately 3 and 9 months following their return to the U.S. Additionally, we evaluated associations of socio-demographic characteristics, prior deployment history, combat/deployment stress, personal life stress during deployment (e.g., relationship, family, financial problems), pre- and peri-deployment mental health, and pre-deployment binge drinking with risk of incidence and persistence of both heavy drinking and AUD/SUD at 3 months post-deployment. To further extend the literature on military deployment and alcohol misuse, we utilized the multiple post-deployment PPDS assessments to determine which of the pre- and peri-deployment risk factors contributed to prediction of chronic heavy drinking and AUD/SUD (i.e., alcohol misuse that was present at both 3 and 9 months post-deployment).

Method

Participants and Procedures

The Pre/Post Deployment Study (PPDS) is a multi-wave panel survey of U.S. Army soldiers in 3 Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs). Baseline (T0) assessment was conducted during Q1 of 2012, 1–2 months before deployment of the BCTs to Afghanistan. Follow-up assessment occurred within 1 month of re-deployment of the BCTs to the U.S. (T1) and at approximately 3 months post-deployment (T2) and 9 months post-deployment (T3). Participants gave written, informed consent for the self-administered questionnaires (SAQs). Baseline SAQ respondents also were asked for consent for collection of blood samples, linkage of Army and Department of Defense (DoD) administrative records to their SAQ responses, and contact for participation in future assessments. Procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of all collaborating organizations.

At T0, 9949 soldiers were present for duty in the 3 BCTs and 9488 (95.3%) consented to the SAQ. Of those who consented, 8558 (86.0%) provided complete data and consent for Army/DoD record linkage. The subpopulation of interest for this investigation was T0 participants with complete SAQ data who subsequently deployed to Afghanistan (n=7742). Because the analysis used data from all waves, the sample was restricted to the 60.0% of deployed soldiers who completed all follow-ups (n=4645).

To mitigate impacts of selection factors and enhance generalizability of results to the broader population of deployed soldiers, weights were developed and applied in all analyses (Heeringa et al., 2010). Combined analysis weights include: (1) a propensity-based weighting adjustment for baseline attrition due to incomplete surveys and inability to link to administrative data (e.g., due to absence of soldier consent); (2) post-stratification to map the observed sample of 7742 eligible PPDS soldiers to key demographic and Army service characteristics of soldiers in the three combined BCTs that deployed to Afghanistan after the T0 interview dates; and (3) a propensity-based attrition adjustment to account for the fact that 3097 of the 7742 T0 deployed cohort did not have complete data in one or more of the 3 follow-up waves. More information about weighting of Army STARRS data can be obtained elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2013b).

Measures

Alcohol use outcomes.

The T0, T2, and T3 surveys assessed frequency of alcohol binges (5 or more drinks of alcohol on the same day) during the past 30 days (never, less than 1 day a week, 1–2 days a week, 3–4 days a week, and every or nearly every day; coded 0–4). Following the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration definitions of binge drinking (5 or more alcoholic drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days) and heavy drinking (5 or more drinks…5 or more days in the past 30 days), ratings ≥1 were coded positive for past-month Binge Drinking (BD) and ratings ≥2 were coded positive for past-month Heavy Drinking (HD). Missing alcohol binge frequency data were rare (<0.5% at each wave) and coded “0” to yield conservative estimates.

Diagnoses of AUD/SUD were based on items from the self-administered Composite International Diagnostic Interview Screening Scales (CIDI-SC; Kessler and Ustun, 2004), which assessed negative consequences of alcohol and/or drug use and symptoms of dependence. An algorithm employing respondents’ ratings was used to diagnose AUD/SUD and results were validated against structured clinical interviews in the Army STARRS clinical reappraisal study (Kessler et al., 2013c). In the T0 survey, respondents endorsing any lifetime alcohol or drug use rated AUD/SUD items in reference to the period when they used the most alcohol (for those with no lifetime use of other drugs), drugs (for those with no lifetime use of alcohol), or alcohol or drugs (for those with lifetime alcohol and other drug use); yielding lifetime AUD/SUD diagnoses. For T2 and T3 surveys, AUD/SUD items were rated in reference to the past 30 days, yielding past-month AUD/SUD diagnoses. AUD/SUD was not assessed at T1.

Because the surveys did not establish whether AUD/SUD symptoms were due to alcohol or drug use (or both), non-alcohol drug use was examined among respondents with AUD/SUD at T2 and at T3. The T2 and T3 surveys assessed past 30-day use of marijuana/hashish; spice/synthetic marijuana; and any other illegal drug; and past 30-day misuse of prescription stimulants, tranquilizers/sedatives, and analgesics. Among respondents with AUD/SUD at T2, 10.0% endorsed use of any non-alcohol drug 1–2×/week or more during the month prior to assessment. The same proportion (10.0%) of those with AUD/SUD at T3 endorsed non-alcohol drug use 1–2×/week or more in the month prior to the T3 assessment. These data suggest that a large majority of AUD/SUD was in fact AUD.

Socio-demographic and Army service variables.

Age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, highest educational degree, and number of prior deployments were considered as predictors of alcohol misuse. BCT was adjusted for in all models.

Combat/deployment stress and life stress.

The T1 survey inquired how many times soldiers had experienced 14 highly stressful/traumatic events during the index deployment. Frequency ratings were discretized (0/1 or 0/1/2) and summed to create a Deployment Stress Scale (DSS; range=0–16; Supplementary Table 1). The T1 survey also assessed stress during deployment that arose from 7 domains of soldiers’ lives (rated none, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe; coded 0–4). Exploratory factor analysis using minimum residual estimation and promax rotation indicated that 2 latent factors best explained the covariance of these ratings (Supplementary Table 2). Two life stress variables were therefore derived. The first was Personal Life Stress (PLS), quantified as the sum of ratings of stress from finances, romantic relationships, legal problems, family relationships, and problems experienced by loved ones (range=0–20; Cronbach’s α=.76). The second was Military Life Stress (MLS), or the sum of ratings of stress from problems with chain of command and fellow unit members (range=0–8; α=.73). For regression analysis, DSS, PLS, and MLS scores were standardized to facilitate interpretation of results. Standard scores of 1.0 and 2.0 were considered “above-average stress” and “high stress,” respectively.

Pre- and peri-deployment mental health.

Regression models included a variable indicating presence versus absence of any past-month PTSD, major depressive episode (MDE), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), or suicidal ideation (SI) at T0. PTSD, MDE, and GAD diagnoses were based on items from the CIDI-SC (Kessler and Ustun, 2004) and PTSD Checklist (Weathers et al., 1993). Validation of these diagnoses was the focus of a prior report (Kessler et al., 2013c). SI was established with an expanded self-report version of the Columbia Suicidal Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., 2011).

Models also included indicators of soldiers’ mental health during deployment. The T1 survey contained 5 items assessing PTSD symptoms during deployment; ratings of these items were summed to quantify overall severity of PTSD symptoms during deployment (range=0–20; α=.84). The T1 survey items assessing MDE and GAD symptoms (7 items total) had excellent internal consistency (α=.90) and were summed to quantify overall severity of MDE/GAD symptoms during deployment (range=0–28). The peri-deployment PTSD and MDE/GAD symptom severity measures were standardized prior to regression analysis to facilitate interpretation of results.

Data Analysis

Weighted prevalence of the following was calculated: 30-day BD and HD at T0, T2, and T3; lifetime AUD/SUD at T0; and 30-day AUD/SUD at T2 and T3. Weights-adjusted logistic regression models were fit to estimate associations of hypothesized risk factors with onset and persistence of HD and AUD/SUD. Models of onset of HD were estimated for soldiers who denied past-month HD at T0; models of onset of AUD/SUD were estimated for soldiers without lifetime AUD/SUD at T0, and persistence models were estimated for soldiers who endorsed the outcome under consideration at T0. Onset and persistence of HD and AUD/SUD at T2 were the primary outcomes. To ascertain which risk factors were associated with chronic post-deployment alcohol misuse, HD and AUD/SUD that were present at both T2 and T3 were considered secondary outcomes.

The following independent variables were included in all models: sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, BCT, number of prior deployments, and pre-deployment emotional disorder (from T0); and combat/deployment stress, personal life stress, military life stress, peri-deployment PTSD symptom severity, and peri-deployment MDE/GAD symptom severity (from T1). Pre-deployment past-month BD was included in models of new-onset HD and AUD/SUD.

PPDS data are clustered (by BCT and administration session) and weighted; therefore, the design-based Taylor series linearization method was used to estimate standard errors. Multivariable significance was examined using design-based Wald X2 tests. Two-tailed p<.05 was considered significant. Analyses were conducted using R Version 3.3.2 (R Core Team, 2013).

Results

Descriptive findings

Weighted prevalence of past-month binge drinking, heavy drinking, and AUD/SUD is shown in Table 1. More than half of soldiers endorsed BD at pre-deployment and 3 months post-deployment; lower prevalence was observed 9 months post-deployment. The rate of HD was relatively stable, with approximately one-quarter of soldiers endorsing past-month HD at each wave. Past-month AUD/SUD was slightly more prevalent at 9 months post-deployment than at 3 months post-deployment. Past-month AUD/SUD was not assessed at the pre-deployment assessment; however, prevalence of lifetime AUD/SUD at T0 was 20.4% (SE=0.7%).

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence of past-month binge drinking, heavy drinking, and AUD/SUD among U.S. Army soldiers pre- and post-deployment (n=4645)

| Pre-deployment (T0) | 3 months post-deployment (T2) | 9 months post-deployment (T3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binge Drinking | 52.5% (1.0%) | 52.5% (1.0%) | 41.3% (0.9%) |

| Heavy Drinking | 23.3% (0.7%) | 26.1% (0.8%) | 22.3% (0.7%) |

| AUD/SUD | - | 6.8% (0.4%) | 10.4% (0.5%) |

Note. AUD/SUD=Alcohol or Substance Use Disorder. Values are weighted prevalence (standard error). Analysis sample was comprised of Pre/Post Deployment Study respondents who completed surveys at all 4 waves: pre-deployment (T0), within 1 month of re-deployment to the U.S. (T1), 3 months post-deployment (T2), and 9 months post-deployment (T3). No data are shown for T1 because neither alcohol binge frequency nor AUD/SUD were assessed at that wave. The T0 survey did not assess past-month AUD/SUD; prevalence of lifetime AUD/SUD at T0 was 20.4% (0.7%).

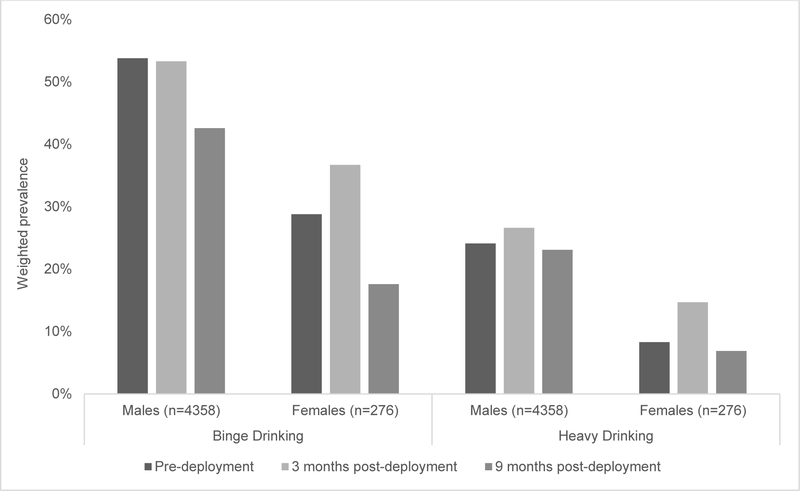

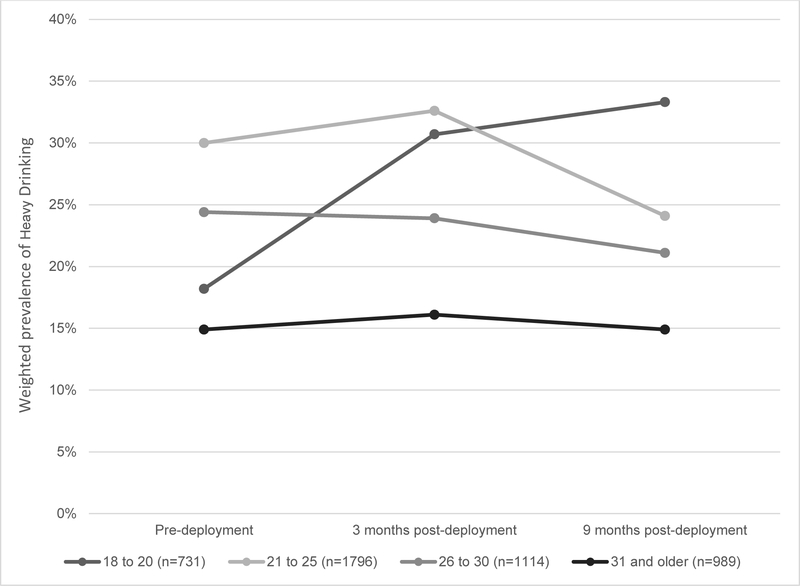

Demographic differences in prevalence of BD, HD, and AUD/SUD were examined and full results appear in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. Women exhibited lower prevalence of BD, HD, and AUD/SUD than men at all waves (see Figure 1 for BD and HD results). Relative to White soldiers, Black and Asian soldiers displayed lower prevalence of BD (all waves), HD (all waves except T3), and lifetime AUD/SUD at T0. Whereas other age groups exhibited stable or declining rates of BD and HD from pre-deployment to 9 months post-deployment, the youngest soldiers (aged 18–20) displayed substantial increases in BD and HD over the same period (see Figure 2 for HD results).

Figure 1.

Weighted prevalence by gender of binge drinking and heavy drinking at pre-deployment (T0), 3 months post-deployment (T2), and 9 months post-deployment (T3). Group n’s total slightly less than 4645 due to rare missing gender data. Prevalence of binge drinking and heavy drinking was lower among women than men at all waves [X2(1)=21.98 to 63.42, ps<.001].

Figure 2.

Weighted prevalence by age group of heavy drinking at pre-deployment (T0), 3 months post-deployment (T2), and 9 months post-deployment (T3). Group n’s total slightly less than 4645 due to rare missing age data. Prevalence of heavy drinking differed by age group at all waves [X2(3)=85.01 to 92.02, ps<.001].

Nearly 1 in 10 soldiers (9.6%, SE=0.4%) had past-month PTSD, MDE, GAD, or SI at T0. On average, soldiers were exposed to 4 combat/deployment stressors during their deployment to Afghanistan [mean DSS=3.98, SD=2.72, observed range=0–15]. Note that this value represents distinct types of combat/deployment stressors encountered – not total number of stressful experiences, which could have been higher in number (see Supplementary Table 1 for DSS scoring details). Reported levels of personal life stress, military life stress, PTSD symptoms, and MDE/GAD symptoms during deployment were generally mild [mean PLS=2.68, SD=3.10, range=0–20; mean MLS=1.73, SD=1.89, range=0–8; mean T1 PTSD score=3.18, SD=3.63, range=0–20; mean T1 MDE/GAD score=5.56, SD=5.20, range=0–28].

Risk factors for onset and persistence of heavy drinking

New-onset of HD post-deployment.

Male sex, younger age, never-married status, pre-deployment BD, and greater personal life stress during deployment were associated with increased odds of onset of HD at T2 among soldiers who denied HD at T0 (Table 2). The adjusted odds-ratio characterizing the association of personal life stress with HD onset indicates that soldiers with above-average (z=1.00) and high personal stress (z=2.00) during deployment exhibited 20% and 44% increased risk of post-deployment HD onset, relative to those with average personal stress during deployment. Prior deployments, combat/deployment stress, military life stress, and pre- and peri-deployment mental health factors were not significantly related to onset of HD.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds of onset and persistence of post-deployment Heavy Drinking among Army STARRS Pre/Post Deployment Study respondents

| Adjusted Odds-Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Heavy Drinking post-deployment (n=3575) | Persistence of Heavy Drinking from pre- to post-deployment (n=1070) | |||

| Any HD | Chronic HD1 | Any HD | Chronic HD1 | |

| Soldier characteristics (assessed at T0) | ||||

| Age, y | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | 0.94 (0.91–0.98) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) |

| Wald X2(1) | 10.82** | 8.21** | 0.00 | 0.49 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) | 0.35 (0.15–0.82) | 1.57 (0.76–3.23) | 0.63 (0.20–2.01) |

| Wald X2(1) | 5.16* | 5.76* | 1.49 | 0.61 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.75 (0.53–1.06) | 0.84 (0.51–1.40) | 0.81 (0.52–1.27) | 0.76 (0.47–1.23) |

| Asian | 0.66 (0.41–1.07) | 0.90 (0.47–1.73) | 0.36 (0.16–0.84) | 0.49 (0.23–1.01) |

| Other | 1.21 (0.84–1.73) | 1.44 (0.91–2.28) | 0.93 (0.57–1.53) | 0.63 (0.37–1.08) |

| Wald X2(3) | 9.43* | 3.74 | 6.13 | 7.96* |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | 0.88 (0.64–1.22) | 0.86 (0.55–1.37) | 0.70 (0.45–1.08) | 0.92 (0.56–1.51) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.56 | 0.40 | 2.59 | 0.12 |

| Education | ||||

| High school degree | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| General equivalency diploma | 0.69 (0.42–1.15) | 0.98 (0.46–2.09) | 0.82 (0.50–1.37) | 0.81 (0.49–1.35) |

| College degree | 0.85 (0.63–1.15) | 1.10 (0.79–1.53) | 1.10 (0.80–1.52) | 0.78 (0.50–1.22) |

| Wald X2(2) | 2.51 | 0.41 | 1.05 | 2.17 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.21 (0.85–1.70) | 1.02 (0.53–1.96) | 1.24 (0.77–1.98) | 0.92 (0.61–1.39) |

| Never married | 1.44 (1.12–1.85) | 1.79 (1.28–2.50) | 1.51 (1.07–2.12) | 1.23 (0.91–1.66) |

| Wald X2(2) | 8.84* | 12.42** | 5.42 | 2.55 |

| Pre-deployment factors (assessed at T0) | ||||

| Prior Deployments | ||||

| Zero | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| One | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 0.77 (0.49–1.20) | 0.97 (0.70–1.35) | 1.12 (0.75–1.68) |

| Two or more | 0.80 (0.58–1.09) | 1.00 (0.59–1.68) | 1.19 (0.83–1.70) | 1.08 (0.64–1.80) |

| Wald X2(2) | 2.56 | 1.75 | 1.24 | 0.33 |

| Past-month Binge Drinking | 3.21 (2.57–4.02) | 2.69 (1.89–3.82) | - | - |

| Wald X2(1) | 104.68*** | 30.52*** | - | - |

| Past-month PTSD, MDE, GAD, or SI | 0.78 (0.52–1.17) | 0.76 (0.43–1.35) | 0.97 (0.58–1.63) | 0.77(0.46–1.29) |

| Wald X2(1) | 1.48 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| Peri-deployment factors (assessed at T1) | ||||

| Combat/deployment stress (standardized) | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 1.11 (0.95–1.30) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 1.73 |

| Personal life stress (standardized) | 1.20 (1.06–1.35) | 1.21 (0.98–1.49) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) | 1.03 (0.88–1.21) |

| Wald X2(1) | 8.64** | 3.08 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Military life stress (standardized) | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) | 0.94 (0.77–1.13) | 0.97 (0.84–1.10) | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.60 |

| PTSD symptom severity (standardized) | 1.14 (0.99–1.30) | 1.10 (0.91–1.33) | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 0.95 (0.79–1.16) |

| Wald X2(1) | 3.43 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 0.22 |

| MDE/GAD symptom severity (standardized) | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) | 1.03 (0.81–1.32) | 1.20 (1.02–1.40) | 1.21 (0.95–1.55) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.08 | 0.07 | 5.09* | 2.33 |

Note. CI=confidence interval; HD=heavy drinking; PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder; MDE=major depressive episode; GAD=generalized anxiety disorder; SI=suicidal ideation. Each column displays the results for a separate weights-adjusted logistic regression model. Models also adjusted for Brigade Combat Team. Significant adjusted odds ratios (where the overall Wald X2 test is also statistically significant) are bolded.

p<.05;

p<.005;

p<.0005.

Chronic HD was defined as heavy drinking that was present at both 3 months and 9 months post-deployment (i.e., at both T2 and T3).

Most (62.0%) new HD observed at T2 had remitted by T3 – i.e., frequency of alcohol binges dropped back below the threshold for HD. When onset of chronic HD (present at T2 and T3) was specified as the outcome, similar risk factors were evident. Male sex, younger age, never married status, and pre-deployment BD were significantly associated with onset of chronic HD. However, the association of personal life stress during deployment with onset of chronic HD was not statistically significant (p=.079; Table 2).

Persistence of HD from pre-to-post deployment.

The hypothesized risk factors generally lacked substantive associations with persistence of HD from pre- to post-deployment. Only peri-deployment MDE/GAD symptoms were associated with persistence of HD at T2 among soldiers who endorsed HD at T0 (Table 2). Soldiers with above-average (z=1.00) and high MDE/GAD symptoms (z=2.00) during deployment exhibited 20% and 43% increased risk of HD persistence at T2, relative to those with average distress during deployment. MDE/GAD symptoms were not associated with chronic persistence of HD at T2 and T3 (p=.13; Table 2).

Risk factors for incidence and persistence of AUD/SUD

Incidence of AUD/SUD post-deployment.

Pre-deployment BD and greater personal life stress during deployment were associated with increased risk of AUD/SUD at T2 among soldiers without lifetime AUD/SUD at T0 (Table 3). Relative to average personal stress during deployment, above-average personal stress was associated with 54% increased risk of incidence of AUD/SUD and high personal stress was associated with more than doubled (AOR=2.36) odds of incidence of AUD/SUD.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds of onset and persistence of post-deployment AUD/SUD among Army STARRS Pre/Post Deployment Study respondents

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence of AUD/SUD post-deployment (n=3729) | Persistence of AUD/SUD from pre- to post-deployment (n=916) | |||

| Any AUD/SUD | Chronic AUD/SUD1 | Any AUD/SUD | Chronic AUD/SUD1 | |

| Pre-deployment factors (assessed at T0) | ||||

| Number of prior deployments | ||||

| Zero | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| One | 0.57 (0.30–1.05) | 0.52 (0.27–1.01) | 0.94 (0.64–1.40) | 1.05 (0.63–1.73) |

| Two or more | 0.81 (0.40–1.65) | 0.58 (0.27–1.25) | 0.72 (0.50–1.04) | 0.84 (0.55–1.28) |

| Wald X2(2) | 3.40 | 4.47 | 3.02 | 0.86 |

| Past-month binge drinking | 1.85 (1.27–2.70) | 1.93 (1.26–2.95) | - | - |

| Wald X2(1) | 10.30** | 9.09** | - | - |

| Past-month PTSD, MDE, GAD, or SI | 0.77 (0.38–1.58) | 0.54 (0.24–1.22) | 0.84 (0.44–1.62) | 1.06 (0.52–2.13) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.50 | 2.22 | 0.27 | 0.02 |

| Peri-deployment factors (assessed at T1) | ||||

| Combat/deployment stress (standardized) | 1.22 (0.96–1.55) | 1.29 (0.97–1.70) | 1.05 (0.90–1.23) | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) |

| Wald X2(1) | 2.61 | 3.07 | 0.34 | 1.96 |

| Personal life stress (standardized) | 1.54 (1.25–1.89) | 1.72 (1.41–2.09) | 1.19 (0.99–1.44) | 1.30 (1.08–1.56) |

| Wald X2(1) | 16.99*** | 28.48*** | 3.49 | 7.80** |

| Military life stress (standardized) | 1.02 (0.89–1.16) | 1.06 (0.83–1.35) | 1.20 (1.02–1.41) | 1.07 (0.89–1.27) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.08 | 0.22 | 5.04* | 0.49 |

| PTSD symptoms (standardized) | 1.04 (0.77–1.40) | 0.94 (0.64–1.37) | 0.93 (0.72–1.20) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.88 |

| MDE/GAD symptoms (standardized) | 1.01 (0.72–1.42) | 0.99 (0.69–1.44) | 1.23 (0.90–1.70) | 1.24 (0.92–1.68) |

| Wald X2(1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.69 | 1.97 |

Note. AUD/SUD=Alcohol or Substance Use Disorder; CI=confidence interval; PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder; MDE=major depressive episode; GAD=generalized anxiety disorder; SI=suicidal ideation. Each column displays the results for a separate weights-adjusted logistic regression model. To streamline the table, soldier characteristics included in the models (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and marital status) are omitted; none displayed significant associations with incidence or persistence of AUD/SUD (ps>.10). Models also adjusted for Brigade Combat Team. Significant adjusted odds ratios (where the overall Wald X2 test is also statistically significant) appear in bold.

p<.05;

p<.005;

p<.0005.

Chronic AUD/SUD was defined as the disorder being present at both 3 months and 9 months post-deployment (i.e., at both T2 and T3).

Nearly two-thirds (64.0%) of new-onset AUD/SUD persisted at T3. The same factors – pre-deployment BD and personal stress during deployment – were associated with increased risk of incidence of chronic AUD/SUD (i.e., at T2 and T3; Table 3). Odds of incidence of chronic AUD/SUD were 72% higher among soldiers with above-average personal stress and nearly tripled (AOR=2.94) for soldiers with high personal stress, relative to those with average personal stress during deployment.

Persistence of AUD/SUD from pre- to post-deployment.

Among soldiers with lifetime AUD/SUD at T0, only greater military life stress during deployment was significantly associated with persistence of the disorder at T2 (Table 3). Compared to soldiers with average military life stress, odds of persistence of AUD/SUD at T2 were 20% and 45% higher among soldiers with above-average and high military life stress, respectively. The association of personal life stress severity with persistence of AUD/SUD at T2 was not statistically significant (p=.062); however, greater personal life stress during deployment was significantly associated with chronic persistence of AUD/SUD at T2 and T3 (Table 3). Relative to those with average personal life stress during deployment, odds of persistence of AUD/SUD at both T2 and T3 were 30% and 69% higher among soldiers with above-average and high personal stress, respectively.

Discussion

This prospective, longitudinal study of U.S. Army soldiers from three Brigade Combat Teams reveals associations between personal life stress during deployment and a range of post-deployment alcohol misuse outcomes. Among soldiers with no lifetime AUD/SUD pre-deployment, high levels of personal life stress during deployment (defined as standard score of 2.00 or higher on the PLS measure) were associated with doubled risk of incidence of AUD/SUD at 3 months post-deployment; and nearly tripled risk of incidence of chronic AUD/SUD observed at 3 and 9 months post-deployment. In addition, personal life stress during deployment predicted onset of heavy drinking among soldiers who denied drinking heavily pre-deployment and chronic persistence of AUD/SUD (at both 3 and 9 months post-deployment) among soldiers with the disorder earlier in life. Binge drinking shortly before deployment also portended onset of more serious alcohol misuse post-deployment; reflected in tripled odds of onset of heavy drinking and nearly doubled odds of incidence of AUD/SUD. In addition to predicting these outcomes at a single post-deployment time point, pre-deployment binge drinking predicted onset of chronic heavy drinking and AUD/SUD that were present at both 3 and 9 months post-deployment.

The PPDS survey did not permit differential diagnosis of AUD versus SUD due to non-alcohol drug use. Available evidence suggests the large majority of AUD/SUD in this sample was in fact AUD; only 10% of respondents with AUD/SUD at either post-deployment assessment endorsed regular use of any non-alcohol drug. Prior work also indicates that AUD is more common than drug abuse/dependence among servicemembers (Fink et al., 2016). Chronicity (persistence at T3) of two-thirds of AUD/SUD with post-deployment onset argues against characterization of these new disorders as transient reactions; and may reflect more enduring stress/adjustment demands associated with deployment to a combat zone and subsequent re-deployment to the U.S. While chronicity was the norm for AUD/SUD with post-deployment onset, a minority of new-onset heavy drinking persisted at T3. Considered together, these findings suggest that presence of abuse or dependence symptoms shortly following return from deployment – as opposed to increased alcohol consumption per se – merit greatest concern.

The absence of associations of combat stress severity with the alcohol misuse outcomes is counterintuitive, but largely converges with results of two other studies that jointly examined predictive effects of combat and personal stress (Cerda et al., 2014, Thandi et al., 2015). Although underlying explanations for the greater apparent influence of personal (versus combat) stressors were not explored in the current analysis, some possibilities meriting future study are: continuance of personal stressors into the post-deployment period (versus offset of deployment stress); soldier perception of drinking as a more effective coping tool for everyday stress than for combat stress; concentration of other vulnerability characteristics (e.g., traits predisposing individuals to alcohol misuse) among soldiers with greater personal stress; and increased resilience among those with low stress arising from their personal lives (e.g., relationships are stable/supportive).

While we conclude that severity of combat stress was not independently associated with post-deployment alcohol misuse in this cohort, we make no inference regarding the effects of deployment (with or without combat exposure) per se on risk of alcohol misuse. A previous large-scale prospective analysis from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) addressed that question and found that, relative to not deploying, deployment with combat exposure (but not deploying without combat exposure) was associated with increased risk of onset of binge drinking among active-duty personnel; and with onset of binge drinking, heavy drinking, and alcohol-related problems among Reserve/National Guard personnel (e.g., Jacobson et al., 2008). We cannot make similar comparisons, as all soldiers in the current study deployed to Afghanistan – with most reporting exposure to several combat stressors. Future research should examine the effects of personal life stress and other risk factors for alcohol misuse in samples of servicemembers deployed to non-combat positions.

Contrary to expectation, pre-deployment emotional disorder was not associated with increased risk of post-deployment heavy drinking or AUD/SUD. Peri-deployment PTSD symptoms also lacked associations with the alcohol misuse outcomes; and peri-deployment MDE/GAD symptoms only exhibited an association with persistence of HD from pre-deployment to 3 months post-deployment. These largely null findings diverge from results of prior studies that found relationships between PTSD, MDE, and alcohol misuse. Among 358 National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq, PTSD symptom severity was associated with increased risk of new-onset AUD (Kehle et al., 2012). Baseline symptoms of PTSD and/or MDE contributed to prediction of incidence of alcohol-related problems (endorsing 1 or more indicators of alcohol abuse) – but not incidence of binge or heavy drinking – in the aforementioned MCS investigation that included both deployed and non-deployed servicemembers (Jacobson et al., 2008). Disparities in study results may reflect differences in sample characteristics or in the consideration or operationalization of mental health and other predictor variables. Although robust predictive effects of mental health variables were not found in this analysis, alcohol misuse displays consistent cross-sectional associations with PTSD, MDE, and other disorders in military samples (Stein et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2010); thus, co-occurring mental health problems must be considered in clinical interventions and other efforts to reduce hazardous drinking and AUD/SUD.

Male, younger, and never-married soldiers displayed increased odds of onset of heavy drinking post-deployment, converging with previous findings of elevated risk of hazardous drinking in these subgroups (Boulos and Zamorski, 2016, Jacobson et al., 2008). The marked increase in risky drinking pre- to post-deployment among soldiers aged 18–20 distinguishes them from others and signals that young soldiers who deploy (particularly those possessing other risk factors) may be a subgroup to consider for targeted prevention efforts, even if the rise is partly attributable to some of them attaining legal drinking age between assessments.

More generally, this study conveys information regarding the scope of alcohol misuse among Army soldiers shortly before and at multiple points after their deployment to a combat zone. Approximately half of respondents reported binge drinking and nearly one-quarter endorsed heavy drinking during the month before pre-deployment assessment. Although differences in study design preclude definitive comparisons, pre-deployment prevalence of heavy drinking in this sample (23%) appears similar to prevalence of a related outcome (regular binge drinking; 27%) among Navy/Marine Corps personnel preparing to deploy (Harbertson et al., 2016).

Typical scheduling of the Army’s Post-Deployment Health Reassessment (PDHRA) places it in closest proximity to the PPDS T2 assessment. Given that soldiers endorsing heavy drinking would likely score in the high-risk range, it is striking that T2 prevalence of heavy drinking was twice the reported rate of “high risk for alcohol abuse” among PDHRA respondents during 2008–2014 (Hurt, 2015). This may signal under-estimation of the true scope of alcohol misuse when non-confidential forms of assessment such as the PDHRA are used (Warner et al., 2011).

Finally, substantially higher rates of past-month binge and heavy drinking were observed among PPDS respondents (at all waves) compared to a cohort of new soldiers (Stein et al., 2017). Higher prevalence of hazardous drinking among PPDS respondents could reflect increased alcohol misuse with longer Army tenure, selection of light drinkers/abstainers out of Army service, or differences in demographic composition or other characteristics of the two samples. Potential contributions of these factors should be explored in future research.

Novel aspects of the current investigation include availability of outcome data at both 3 and 9 months post-deployment; inclusion of number of prior deployments as a potential risk factor; increased granularity in measurement of combat stress exposure (0–16 index versus dichotomous characterization of deployment status or combat exposure); and joint consideration of a range of peri-deployment stressors and symptoms in relation to post-deployment heavy drinking and AUD/SUD.

The study also has several limitations. Conclusive differential diagnosis of AUD versus SUD was not possible. Retrospective self-report data are vulnerable to recall and response biases; in the case of alcohol and drug use assessment, under-reporting may occur. Estimates of non-alcohol drug use might be more susceptible to this bias than estimates of alcohol use given fear of repercussions for admitting drug use in light of the Army’s zero-tolerance policy. Under-reporting of both alcohol and drug use could have been accentuated at the pre-deployment assessment, due to heightened desires to appear “combat-ready”.

Weights were applied to mitigate impacts of attrition and to enhance generalizability to the broader population of deployed soldiers. Nevertheless, selection factors may have influenced the results (i.e., soldiers who completed all assessments may have differed from the larger population of soldiers on variables not adjusted for via weights or covariates). The T0 survey did not assess lifetime HD; thus, new-onset of HD could only be defined in relation to drinking during the month before T0 assessment. Finally, low representation limited power to detect risk differences for certain subgroups (e.g., females). More research is needed to investigate whether sex differences are present with respect to risk factors for post-deployment alcohol misuse.

In conclusion, pre- and post-deployment alcohol misuse was common among soldiers from 3 U.S. Army Brigade Combat Teams that deployed to Afghanistan. Severity of personal life stress during deployment – but not severity of combat stress – was associated with post-deployment onset of heavy drinking and incidence and persistence of AUD/SUD. Pre-deployment binge drinking also predicted onset of heavy drinking and AUD/SUD post-deployment. Detection of risky drinking occurring shortly before deployment would provide an opportunity for early intervention to prevent onset of more severe alcohol-related problems. Additionally, efforts to identify and assist soldiers experiencing substantial personal life stress during deployment could prove beneficial not only for reduction of alcohol misuse, but possibly for overall mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System)

Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan), James Wagner, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School)

Army liaison/consultant: Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (USAPHC (Provisional))

Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Chia-Yen Chen DSc (Harvard Medical School); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Joel Gelernter (Yale University); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E. McCarroll, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); CDR Patcho Santiago, MD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Jordan W. Smoller, MD, ScD (Harvard Medical School); and Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School).

Financial Support: Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001-15-2-0004). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Stein has in the past three years been a consultant for Actelion, Dart Neuroscience, Healthcare Management Technologies, Janssen, Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Resilience Therapeutics, and Tonix Pharmaceuticals. In the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis; was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, Shire, Takeda; and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. The remaining authors have no financial disclosures.

Ethical standards: The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- Boulos D & Zamorski MA (2016). Contribution of the mission in Afghanistan to the burden of past-year mental disorders in Canadian Armed Forces personnel, 2013. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 61, 64S–76S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Brown JM & Williams J (2013). Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the U.S. military. Substance Use & Misuse 48, 799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M, Richards C, Cohen GH, Calabrese JR, Liberzon I, Tamburrino M, Galea S & Koenen KC (2014). Civilian stressors associated with alcohol use disorders in the National Guard. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 47, 461–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink DS, Calabrese JR, Liberzon I, Tamburrino MB, Chan P, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Reed PL, Shirley E, Goto T, D’Arcangelo N, Fine T & Galea S (2016). Retrospective age-of-onset and projected lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among U.S. Army National Guard soldiers. Journal of Affective Disorders 202, 171–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B & Hasin DS (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbertson J, Hale BR, Watkins EY, Michael NL & Scott PT (2016). Pre-deployment alcohol misuse among shipboard active-duty U.S. military personnel. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51, 185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, West BT & Berglund PA (2010). Applied survey data analysis. Chapman and Hall: Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt L (2015). Post-deployment screening and referral for risky alcohol use and subsequent alcohol-related and injury diagnoses, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2008–2014. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report 22, 7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson IG, Ryan MA, Hooper TI, Smith TC, Amoroso PJ, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD, Wells TS & Bell NS (2008). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. Journal of the American Medical Association 300, 663–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle SM, Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Meis LA, Arbisi PA, Erbes CR & Polusny MA (2012). Predictors of postdeployment alcohol use disorders in National Guard soldiers deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 26, 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Zaslavsky AM, Stein MB, Ursano RJ & Heeringa SG (2013a). Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 22, 267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Hwang I, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Zaslavsky AM, Stein MB, & Ursano RJ (2013b). Response bias, weighting adjustments, and design effects in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 22, 288–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Santiago PN, Colpe LJ, Dempsey CL, First MB, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Fullerton CS, Gruber MJ, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Zaslavsky AM & Ursano RJ (2013c). Clinical reappraisal of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 22, 303–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC & Ustun TB (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13, 93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, Bell MR, Smith B, Boyko EJ, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, Ghamsary M & Hoge CW (2013). Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. Journal of the American Medical Association 310, 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash HB, Fullerton CS, Ramsawh HJ, Ng TH, Wang L, Kessler RC, Stein MB & Ursano RJ (2014). Risk for suicidal behaviors associated with alcohol and energy drink use in the US Army. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 49, 1379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiko MJ, Olmsted KL, Brown JM & Bray RM (2011). Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel. Addictive Behaviors 36, 608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoro CA, Brewer RD, Naimi TS, Moriarty DG, Giles WH & Mokdad AH (2004). Binge drinking and health-related quality of life: Do popular perceptions match reality? American Journal of Preventive Medicine 26, 230–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S & Mann JJ (2011). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 168, 1266–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE & Brewer RD (2015). 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49, e73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson L, Cohen GH, Calabrese JR, Fink DS, Tamburrino M, Liberzon I, Chan P & Galea S (2015). Mental health over time in a military sample: the impact of alcohol use disorder on trajectories of psychopathology after deployment. Journal of Traumatic Stress 28, 547–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Campbell-Sills L, Gelernter J, He F, Heeringa SG, Nock MK, Sampson NA, Sun X, Jain S, Kessler RC, Ursano RJ & Army SC (2017). Alcohol misuse and co-occurring mental disorders among new soldiers in the U.S. Army. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 41, 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandi G, Sundin J, Ng-Knight T, Jones M, Hull L, Jones N, Greenberg N, Rona RJ, Wessely S & Fear NT (2015). Alcohol misuse in the United Kingdom Armed Forces: A longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 156, 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA & Hoge CW (2010). Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Archives of General Psychiatry 67, 614–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB & Army S. c. (2014). The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry 77, 107–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Grieger T, Belenkiy S, Breitbach J, Parker J, Warner CM & Hoge C (2011). Importance of anonymity to encourage honest reporting in mental health screening after combat deployment. Archives of General Psychiatry 68, 1065–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J & Keane T (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.