Abstract

We have previously discovered that the adult Drosophila melanogaster is tolerant to a low O2 environment, withstanding hours of total O2 deprivation without showing any evidence of cell injury. Subsequently, our laboratory embarked on the study of hypoxia tolerance using a mutagenesis and over-expression screens to begin to investigate loss- or gain-of-function phenotypes. Both have given us promising results and, in this paper, we detail some of the interesting results. Furthermore, we have also started several years ago an experimental “darwinian” selection to generate a fly strain that can perpetuate through all of its life cycle stages in hypoxic environments. Through microarrays and bioinformatic analyses, we have obtained genes (e.g., Notch pathway genes) that play an important role in hypoxia resistance. In addition, we also detail a proof of principle that Drosophila genes that are beneficial in fly resistance to hypoxia can also be as well in mammalian cells. We believe that the mechanisms that we are uncovering in Drosophila will allow us to gain insight regarding susceptibility and tolerance to low O2 and will therefore pave the way to develop better therapies for ailments that afflict humans as a consequence of low O2 delivery or low blood O2 levels.

1. Overview

Hypoxia, whether present during physiologic states (e.g., embryogenesis and organ formation) or during pathologic states (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and sickle cell anemia), present a challenge to the organism. Depending on duration and severity, hypoxia can lead to cell injury and death and consequently organ injury and failure. This is well illustrated in diseases that lead to major morbidity and mortality, such as myocardial infarction, cerebro-vascular accidents and brain dysfunction, and placental insufficiency with poor fetal development and potential demise. In fact, the consequences of cerebral and myocardial hypoxia and ischemia are amongst the most severe in the 21st century. Investigations in the past few decades have started to provide some understanding of the fundamental basis of hypoxia and the mechanisms by which it leads to injury. Furthermore we and others have begun to identify also the mechanisms that underlie adaptation to and survival in hypoxia such that the molecules that mediate adaptive effects might lead to new therapeutic targets to protect or reverse hypoxia-induced pathology. Such investigations have taken advantage of a variety of models, from invertebrates to vertebrates and to humans.

Many approaches have been used to study questions regarding hypoxic cell injury due to O2 deprivation. Many investigators, including ourselves have resorted to in-vitro techniques and others to more in-vivo approaches. Some investigators have used acute settings and mostly electrophysiologic techniques, to examine ionic homeostasis (1) but others have relied on morphometric and anatomic approaches. Still others have focused almost exclusively on molecular approaches, especially in settings in which the stress is modest and cells and tissues withstood prolonged periods of hypoxia (2–4). Some of the more recent studies in our laboratory as well as in others, using molecular and genetic approaches, have provided evidence that there are genes that can protect against or predispose to cell injury and death when cells are exposed to O2 deprivation (see below). Some investigators have studied the effect of hypoxia alone but others have combined it to glucose deprivation as well. There are laboratories that have focused on global ischemia and others have studied focal ischemia. It is of no surprise therefore that the results in the literature have been often confusing and sometimes inconsistent. This is compounded also by the fact that experimentally the PO2 in the hypoxia system is not measured and there can be major effects of small changes, especially at the lower levels of O2. Most importantly, these studies are often biased in that the investigators focus on a pathway or a molecule that they are most familiar with or most interested in, trying to find a role for that particular pathway or molecule in hypoxia or ischemia. Clearly, this is not necessarily faulty but it illustrates the idea that often the work that has been published in the past, until probably a few years ago, was focused on themes that might not have been the most important in understanding normative or pathobiological processes.

2. Why Drosophila: A variety of phenotypes and disease conditions

Although flies have been used for over a hundred years, since the days of T. H. Morgan, work on flies focused on being models for human diseases only in the past decade when such work flourished and major discoveries are currently being made. At present, a considerable amount of research in Drosophila is tied to the understanding of behavioral, biochemical or genetic processes at the molecular level and the relation to disease processes in mammals or humans. Examples in point are related, for instance, to the effort that is on-going at present to solve the molecular underpinnings of aging, tumor formation, alcohol intoxication, neuro-degeneration, and memory, to name a few (5–7).

Complex pathways are simpler to elucidate in Drosophila compared to those in vertebrates. Single cell organisms such as yeast and bacteria are useful in determining cell autonomous effects, where the effect is in a single cell, with no interactions between cells. Higher order metazoans, such as vertebrates, often have redundancies in their genomes with several genes able to compensate for one another. Lower order metazoans, such as Drosophila, have far fewer redundancies in their genome and this represents at least one reason why Drosophila is a useful model to study non-cell autonomous effects or ones that require a model organism that undergoes development or has variety of organ systems (5). An example of this can be found in studies of heart development. The discovery of the Drosophila gene tinman, a homeobox transcription factor involved with cardiac specification, and its conservation in vertebrates supplied evidence that conserved pathways controlled cardiac development in both flies and humans (8, 9), driving subsequently the field of cardiac development in humans (10).

Another important example which has illustrated the power of Drosophila as a model system is in the area of triplet repeats and neurological diseases, such as Fragile X syndrome (FXS). In 2002 two groups independently reported that the fly homolog for the protein causing FXS, Fmr1, associates with the RNAi complex in Drosophila (11, 12) and further research in both Drosophila and higher metazoans confirmed the role of FMR1 as an RNA binding protein (13) and showed that Fmr1 mutant flies have impaired long-term memory, analogous to some aspects of mental retardation in humans (13, 14). Finally, a Drosophila model of FXS used to screen a library of small molecules lead to the discovery of 9 especially promising compounds that rescued several FXS phenotypes (14).

More than 15 years ago, a transcriptional factor, named hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α), was discovered. Although at the outset, this factor was presumed to be important for erythropoietin activation only, it is certainly turning out to be a major factor that is more a switch mechanism for hundreds of genes that are activated in order to adapt to the hypoxic stress. This factor is a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of a constitutively expressed HIF-beta subunit and an oxygen-regulated HIF-α subunit. A hypoxia-inducible transcriptional response in Drosophila melanogaster that is homologous to the mammalian HIF-dependent response has already been demonstrated by a number of investigators. In Drosophila, the bHLH-PAS proteins Similar (Sima) and Tango (Tgo) are the functional homologues of the mammalian HIF-α and HIF-β subunits, respectively. HIF-α/Sima is regulated by oxygen, and Sima, but not other Drosophila bHLH-PAS proteins, showed inducible activity following exposure to stimuli which classically activate mammalian HIF-1 including hypoxia, cobaltous ions, and desferrioxamine. In addition, Sima protein accumulated in Drosophila S2 cells following hypoxia. Such findings indicate the existence of functional homologies between Sima and HIF-1α, and that there is conservation which enables Sima to interact with the hypoxia signal transduction system similar to that in mammalian cells. This is another major example where conservation between flies and mammalian species is so striking.

We have been interested in a variety of questions that span from O2 sensing to the cellular and molecular responses to hypoxia and to injury from anoxia. More than twelve years ago, we discovered that the adult fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is acutely tolerant to a low O2 environment, withstanding ~3–4 hours of total O2 deprivation (anoxia) without showing any evidence of cell injury (6, 15–17). We could not distinguish, using light and electron-microscopy, between cells and cellular organelles in the central nervous system of flies that were exposed to anoxia for hours from normoxic control flies. This is clearly remarkable, especially that 3–4 hours of the life of a fly is much longer than this specific absolute time if one translates this in terms of “human” time! Based on these observations, our laboratory embarked on the study of hypoxia tolerance in this organism for the following reasons: a) Drosophila melanogaster is an extremely well studied organism with thousands of stocked mutants and P-element lines (insertional mutations) that cover the majority of its genome; b) ~70% of all known human disease genes are present in Drosophila melanogaster and c) this organism has had a long history of genetic dissection of normative and disease processes (5–7).This opened major avenues for us since the Drosophila has been used so effectively in so many relevant research areas. Indeed, in spite of many advances in monitoring oxygenation, there is still considerable morbidity and mortality arising from conditions with O2 deprivation leading to hypoxic/ischemic damage, especially, in brain. Part of this failure is related to the complexity of the cascade of events that ensue after hypoxia. Hence, we have used Drosophila in our laboratory to solve some of the questions related to tolerance or susceptibility to hypoxia. In this review, the role and importance of genetic models, such as Drosophila melanogaster, are discussed using specific examples illustrating the power of Drosophila genetics as a tool to understand human disease and in this particular case, hypoxic cell injury. We employed three ideas to try to address our questions: 1) mutagenesis and over-expression screens to identify loss-of-function mutants and gain-of-function lines; 2) microarrays on adapted versus naïve flies; and 3) studying cell biology and physiology of genes that seem important in flies and mammals. The hope is to learn from these studies about the fundamental basis of tolerance (and susceptibility) to the lack of O2, and with this knowledge be able to develop better therapies for the future.

3. Forward and Reverse Genetics Approaches and Results from Drosophila

These approaches allow us to use specific techniques and test specific hypotheses aimed at understanding the basis for hypoxia tolerance or susceptibility. Indeed, we have used: 1) a classic or forward genetics approach, in which a phenotype is dissected genetically and a gene or multiple genes are identified that could be responsible for the phenotype of interest, i.e., tolerance or susceptibility to O2 deprivation; 2) reverse genetics, in which gene expression is studied and that the differential gene expression obtained can potentially lead to the understanding of the phenotype of interest; and 3) the study of mechanisms of specific genes in flies in order to understand the cell biology and physiology that is not currently understood in mammals; flies are used here also as a model. In the past several years, we have started to use these approaches in the study of hypoxia in Drosophila melanogaster. Both mutagenesis and over-expression screens were begun to investigate loss-of-function or gain-of-function phenotypes and both have given us promising results (18–26). We have taken advantage of both forward and reverse genetic approaches and have successfully used these in the past to address various questions of interest. For example, we have succeeded during the past 5–6 years in generating a fly strain, through experimental selection (see below) that can live and perpetuate through all of its life cycle stages in extremely low O2 environments. We will detail examples of these approaches below.

a. Forward Genetic Approaches and Results.

Example 1: An adenosine deaminase gene, ADAR

Using the first strategy, or forward genetics, one focuses on defining the phenotype and then isolating the gene(s) responsible for the phenotype after using, for example, a mutagenesis screen. This screen would include a behavioral and/or physiological assay that is essential to uncover those mutants that have either lost or gained function. After such mutants are isolated, the mutations are mapped and the genes cloned. To prove that such genes are responsible for the phenotype, one would resort to various approaches including the injection of a wild-type cDNA of the gene of interest into a mutant embryo, for example, to rescue the phenotype. This is precisely what we have done and, about a few years ago, we obtained very interesting results pertaining to the gene hypnos-2P or ADAR (23). This gene encodes a Drosophila pre-mRNA adenosine deaminase (dADAR) and is expressed almost exclusively in the adult central nervous system. Disruption of the dADAR gene results in totally unedited sodium (Para), calcium (Dmca1A), and chloride (DrosGluCl-α) channels, a very prolonged recovery from anoxic stupor, a vulnerability to heat shock and increased O2 demands, and neuronal degeneration in aged flies. We have also done rescue experiments to ascertain that hypnos-2P or ADAR is the gene that induces the sensitivity to anoxia (Figure 1). These data clearly demonstrate that, through the editing of ion channels as targets, dADAR, for which there are mammalian homologues, is essential for adaptation to altered environmental stresses such as O2 deprivation and for the prevention of premature neuronal degeneration. In addition, these mutant flies recover their evoked potentials after anoxia at a much slower pace than wild-type flies, which is consistent with the behavioral results. Furthermore, in characterizing further the phenotype, we also found that this mutant, although it is anoxia sensitive (loss-of-function mutant for hypoxia resistance), is very resistant to oxidant injury. In addition to phenotypic studies, we have performed studies to determine: 1) the expression of ADAR (23, 27, 28); and 2) the targets that are acted upon by ADAR (18, 24). We found that there are specific regions in the fly CNS where ADAR has high expression. Using a variety of molecular and bio-informatic techniques, we have indeed discovered a number of novel targets which are potentially the target molecules that are important for the phenotype (24).

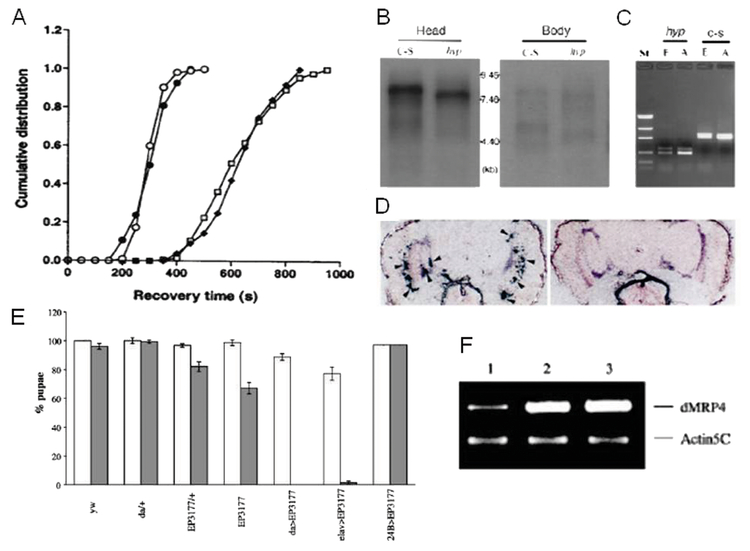

Figure 1.

Results of forward genetic screen: dADAR and dMRP4. A) The prolonged recovery of hypnos-2P (ADAR−/− null) flies can be fully rescued by a wild-type dADAR transgene (○ : hypnose-2P-dADAR; : ● w1118; □: hypnose-2P; ■: hypnose-2P-32B). B) The dADAR transcripts are expressed mainly in adult heads, and the deletion in hypnos-2P is an in-frame deletion. C) The expression of dADAR can be detected by RT-PCR in C-S embryos (6–8 hours). No full-length dADAR transcripts can be detected in hypnos-2P embryos and adults. St, low mass DNA marker; Hyp, hypnos-2P; E, embryos (6–8 hours); A, adults. D) Localization of dADAR transcripts in adult fly heads (left panel; arrowheads). Sense dADAR RNA probe gave no positive signals in the same tissues (right panel). E) Misexpression of dMRP4 reduces viability in Drosophila. Viability was shown as percentage of first instar larvae surviving to pupae, referring to numbers of yw pupae from the normoxic groups as 100%. (□: 21% O2;  : 4% O2). F)

dMRP4 mRNA expression in pupae. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the expression levels of dMRP4 mRNA from 24B>EP(3)3177 pupae exposed to 4% O2 for 10 days (line 2) or reared at 21% O2 (line 3), yw flies were used as control (line 1). (Adapted with permission from Ma E, et al., J Clin Invest 107:685–693, copyright © 2001, by The American Society for Clinical Investigation, and Huang H and Haddad GG, Physiol Genomics 29:260–266, copyright © 2007 by the American Physiological Society).

: 4% O2). F)

dMRP4 mRNA expression in pupae. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the expression levels of dMRP4 mRNA from 24B>EP(3)3177 pupae exposed to 4% O2 for 10 days (line 2) or reared at 21% O2 (line 3), yw flies were used as control (line 1). (Adapted with permission from Ma E, et al., J Clin Invest 107:685–693, copyright © 2001, by The American Society for Clinical Investigation, and Huang H and Haddad GG, Physiol Genomics 29:260–266, copyright © 2007 by the American Physiological Society).

Example 2: A Multi-drug resistance protein, dMRP4

Although we have previously shown that Drosophila melanogaster is hypoxia-tolerant, how this species senses O2 deprivation and how it survives oxygen-limiting conditions are as yet poorly understood. We addressed this question here by testing for anoxic responsiveness in Drosophila adult flies following an over-expression of existing EP lines. In this screen, we identified Drosophila CG14709 gene as a homolog of the human multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) that is tightly regulated to oxygen homeostasis. When this gene product is over-expressed, adult flies profoundly delay their recovery time from anoxia. Ubiquitous expression (with daughterless promoter, da) of dMRP4 (using the EP line 3177, see Figure 2) in adult flies resulted in increased sensitivity to anoxia as they had longer recovery time from anoxic stupor. When exposed to 4% oxygen chronically (throughout its lifespan), constitutive expression of dMRP4 in larvae caused larval lethality due to growth arrest (Figure 1). Mutations of dMRP4 led to a hypersensitive response to acute anoxia in adult flies but had less impact on larval survival under chronic hypoxia compared with dMRP4 over-expression. Selective expression of this gene in neurons, but not in glia or muscles, mirrored the same phenotype as the ubiquitous one. Since neuromuscular transmission and muscle evoked responses have been tightly correlated with the recovery behavior of adult flies during and after anoxia (17), it is interesting to know the role of muscle in anoxia tolerance, in addition to neurons. We addressed this question by targeted expression of dMRP4 specifically in muscles under control of 24B-Gal4. We found that over-expression of dMRP4 in muscles only did not alter the behavioral response to anoxia in adult flies and had no effect on larval survival when exposed to 4% O2. Whereas these results did not completely rule out the potential contribution of muscles to anoxia tolerance, we believe that, based on our results with targeted expression, the dMRP4 activity in neurons mainly accounts for sensing the oxygen changes by Drosophila. In support of this notion, targeted expression of dMRP4 only in larval imaginal discs did not change adult behavior in response to anoxia. Thus, our data suggest novel roles for MRP in vivo: 1) dMRP4 regulates the sensitivity to acute or chronic O2 deprivation, and 2) dMRP expression in neurons is sufficient to induce the sensitivity to O2 in the whole organism.

Figure 2.

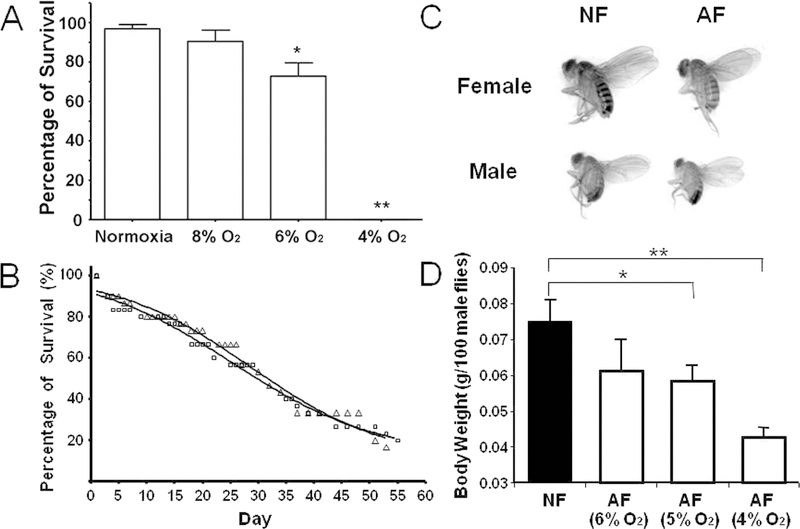

Phenotypic changes in hypoxia-selected Drosophila melanogaster. A) Survival rate of parental Drosophila melanogaster population in hypoxic conditions. The parental population survived well at 8% O2 but their survival rate was reduced at 6%; and 4% O2 was lethal. B) No significant differences were found in lifespan between naïve flies (Δ: NF) and hypoxia-adapted/selected flies (□: AF). The mean lifespan for NF is 33.7±6.2 days (n=180) and the mean lifespan for AF is 33.7±3.9 days (n=220). C) and D) Body size and weight in AF. The body size and weight of AF were significantly reduced, as compared to NF. Data were presented as means ± SD (* p<0.05, **p<0.01; student’s t-test). (Adapted with permission from Zhou D et al., PLoS Genet 4:e1000221, copyright © 2008).

b. Reverse Genetics:

b1. An Experimental Selection Paradigm and a “Darwinian experiment”

Using a reverse genetics approach, we asked whether we can determine which genes are important during hypoxia. We had two ideas. First, we exposed flies to various short durations of hypoxia (minutes to hours) and determined gene expression; subsequently we showed that the alterations in gene expression played a role in hypoxia (see below under acute hypoxia). Secondly, starting from a relatively large pool of alleles, we exposed flies to hypoxia over generations and determined whether the offspring selected under hypoxic pressure had differential gene expression; we proved that these alterations are important.

Unlike forward genetics, reverse genetics studies the function of a gene starting from the gene itself instead of a phenotype. In reverse genetics, a gene's expression is altered using various techniques and the effect of such genetic manipulation on the organism is analyzed. In the past several years, we have successfully combined reverse genetics with the strategies of experimental selection and expression profiling in our studies of hypoxia tolerance or injury in Drosophila. Our approach was to: 1) identify those genes that are differentially expressed in hypoxia, 2) genetically manipulate these genes by various mutagenesis or RNAi strategies, and 3) determine the effect of such manipulations on the response to hypoxia or survival in hypoxia. This strategy has allowed us to study the genetic basis of long-term (over generations) or short-term (hours to days) responses to hypoxia. We summarize here the studies related to the understanding of mechanisms underlying hypoxia tolerance in our newly generated hypoxia-tolerant Drosophila strain (25, 26).

To identify the mechanisms underlying hypoxia tolerance in hypoxia-tolerant animals and to translate such mechanisms into mammals to protect from hypoxia-induced injury is an attractive way to develop new strategies for therapeutic purposes. To do so, we have generated in the past several years a Drosophila strain that can survive perpetually in severe hypoxic environment (i.e., equivalent to 4% O2, an oxygen level at ~4000 meters above Mount Everest). In this experimental selection experiment, a balanced pool of wild-type isogenic lines was used as the parental population which had a significant variability in hypoxia tolerance (1). Hypoxia tolerance of the parental pool was determined at the outset by culturing the F1 embryos of the parental flies under different levels of O2 (e.g., 8%, 6% or 4%). This was important since we needed to determine the starting O2 level for the experimental selection. We found that 6% O2 significantly reduced the survival rate, and 4% O2 was lethal. At 8% O2, however, the majority of embryos (>80%) completed their development and reached the adult stage. Therefore, we initiated the hypoxia selection at 8% O2. In order to maintain the selection pressure, O2 concentration in the selection chambers was gradually decreased by ~1% after a few to several generations. By the 13th generation, we obtained flies that were able to complete development and perpetually live in 5% O2; and by the 32nd generation, flies could live perpetually under 4% of O2, a lethal condition for naïve flies. To test if this hypoxia tolerant trait is heritable, a subset of embryos obtained from the selected flies were collected and cultured under normoxia for several consecutive generations. After 8 generations in normoxia, their embryos were re-introduced into the lethal hypoxic environment (for naïve flies, 4% O2), and again, the majority (>80%) of these embryos completed their development and could be maintained in this extreme condition perpetually. This result strongly suggested that the hypoxia-tolerance in the selected flies was indeed heritable. Furthermore, several remarkable phenotypic changes were observed in the hypoxia-selected flies. For example, the hypoxia-selected flies have a shortened recovery time from anoxia-induced stupor (16), consume more oxygen in hypoxia, and show a significant reduction in cell number and cell size, and a reduction in body weight and size (Figure 2).

To further investigate the genetic basis underlying hypoxia tolerance in this hypoxia-selected Drosophila strain, we determined the global gene expression profiles in 3rd instar larvae and adult flies using cDNA microarrays. One reason for performing the microarrays on both larvae and adult flies is to determine how a stress like hypoxia affects both the developing organism (larvae) and a mature organism (adult). We found 2749 significant alterations (1534 up- and 1215 down-regulated) in the larval stage and 138 significant alterations (95 up- and 43 down-regulated) in the adults (p<0.05 and fold change>1.5). Among them, 51 genes were found to be altered in both larval and adult stages. Interestingly, most of the commonly up-regulated genes encode proteins that are related to stress response and immunity, and the majority of the commonly down-regulated genes encode proteins that are related to metabolism. The significantly altered genes were further categorized based upon their Gene Ontology (GO). We found significant alterations in more than 30 biological processes in both larvae and adult. Most of these processes were related to either defense (especially immune responses, p<0.05) or metabolism (especially carbohydrate and peptide metabolism, p<0.05). Interestingly, most down-regulated genes in larvae encoded proteins related to metabolism (1044 genes including 135 genes that are related to carbohydrate metabolism, p<0.01). In contrast, the genes that were up-regulated belonged to multiple components of signal transduction pathways including EGF, insulin, Notch, and Toll/Imd signaling pathways (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in signaling pathways in hypoxia-selected Drosophila melanogaster at larval and adult stages (p<0.05; NS: not significant).

| Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larvae | Adult | ||

| 1. EGF receptor Signaling pathway | |||

| E(spl) | Enhancer of split Bottom of Form | 1.81 | NS |

| ed | echinoid | 1.85 | NS |

| Egfr | Epidermal growth factor receptor | 1.52 | NS |

| Nrg | Neuroglian | 1.68 | NS |

| spi | spitz | 1.51 | NS |

| 2. Insulin receptor signaling pathway | |||

| Akt1 | Akt1 | 2.20 | NS |

| CG10702 | CG10702 | 1.51 | NS |

| CG11910 | CG11910 | 1.83 | NS |

| chico | chico | 2.10 | NS |

| Pi3K21B | Pi3K21B | 1.59 | NS |

| Pk61C | Protein kinase 61C | 1.51 | NS |

| Pten | Pten | 1.68 | NS |

| 3. JNK cascade | |||

| Aplip1 | APP-like protein interacting protein 1 | −1.57 | NS |

| bsk | basket | 1.99 | NS |

| Cdc42 | Cdc42 | 1.79 | NS |

| Crk | Crk | 1.83 | NS |

| R | Roughened | 1.82 | NS |

| Rho1 | Rho1 | 1.60 | NS |

| Sac1 | Sac1 | −2.18 | NS |

| 4. Notch signaling pathway | |||

| aph1 | anterior pharynx defective 1 | 1.63 | NS |

| Brd | Bearded | 1.65 | NS |

| E(spl) | Enhancer of split Bottom of Form | 1.81 | NS |

| fng | fringe | 1.55 | NS |

| HLHmβ | E(spl) region transcript mβ | 1.64 | 1.60 |

| HLHmδ | E(spl) region transcript mδ | 2.20 | NS |

| HLHmγ | E(spl) region transcript mγ | 1.92 | NS |

| mα | E(spl) region transcript mα | 2.27 | NS |

| m4 | E(spl) region transcript m4 | 2.21 | NS |

| nct | nicastrin | 1.72 | NS |

| O-fut1 | O-fucosyltransferase 1 | 2.74 | NS |

| SP1070 | SP1070 | 2.00 | NS |

| Su(dx) | Suppressor of deltex | −1.60 | NS |

| 5. Toll signaling pathway | |||

| ECSIT | ECSIT | −1.79 | NS |

| ird5 | immune response deficient 5 | 1.78 | NS |

| key | kenny | 1.81 | NS |

| nec | necrotic | −1.73 | NS |

| PGRP-SA | Peptidoglycan recognition protein SA | 2.51 | NS |

| PGRP-SB1 | PGRP-SB1 | 7.56 | 2.03 |

| Pli | Pellino | 1.72 | NS |

| snk | snake | −2.06 | NS |

| Spn27A | Serpin-27A | 1.87 | NS |

| spz | spatzle | 1.55 | −1.71 |

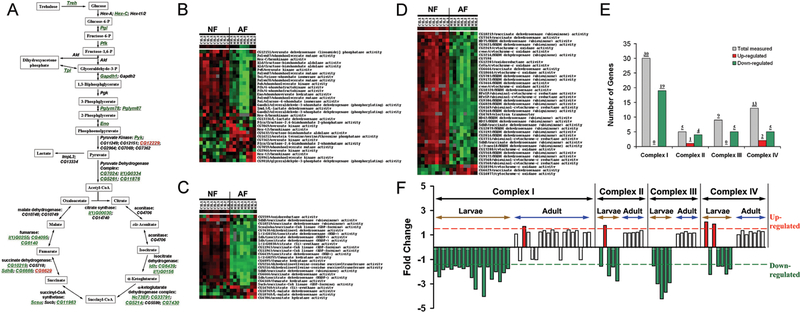

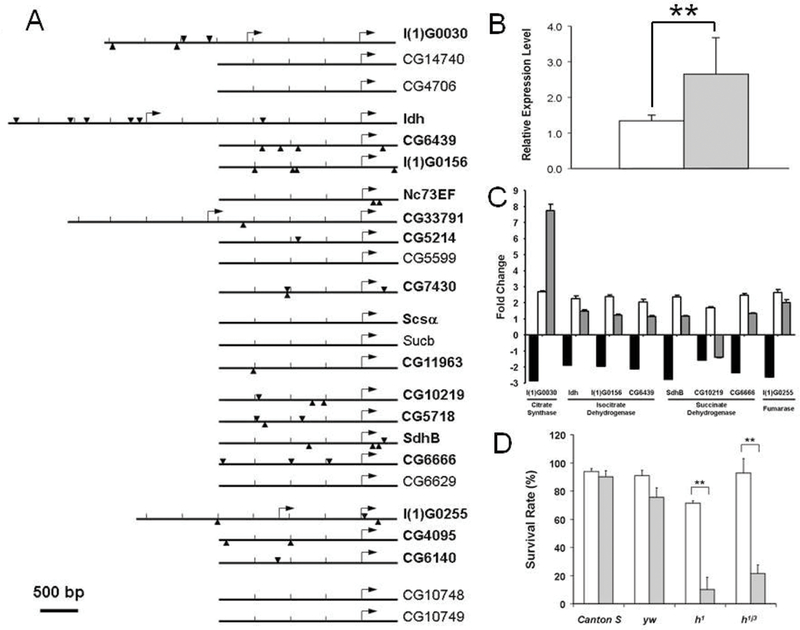

Previous studies based upon metabolic analyses demonstrated that metabolic suppression plays an important role in hypoxia tolerant animals. For example, Hochachka and others have argued that anoxia-tolerant organisms depress their metabolism in order to minimize the mismatch between supply and demand (29–31). While this idea is intuitively appealing, there was no information about how various metabolic enzymes could be coordinated in order to survive severe long lasting hypoxia. In the hypoxia-selected flies, we identified significant changes in the family of genes regulating cellular respiration and metabolism, especially in larvae. Indeed, the majority of the genes were down-regulated. For example, besides one pyruvate kinase isoform (CG12229), most of the genes encoding glycolytic enzymes were dramatically down-regulated. Similarly, the expression of genes encoding TCA cycle, lipid β-oxidation and respiratory chain complexes were also significantly down-regulated, especially in larvae (Figure 3). Since the majority of genes in the TCA cycle were down-regulated, we hypothesized that such down-regulation was coordinated, possibly at a transcriptional level. Therefore, we attempted to identify transcriptional regulators that potentially controlled the coordinated suppression by analyzing the cis-regulatory regions of these down-regulated genes. To do so, the GenomatixSuite (GEMS) software was used to identify transcription factor binding elements in the defined cis-regulatory regions of genes encoding the TCA cycle. We divided the TCA cycle related genes into two groups, one containing the significantly down-regulated genes (as the experimental group, 16 genes), and the other containing the insignificantly altered or up-regulated genes (as the reference group, 8 genes). Of major interest was that the binding elements of the Drosophila transcriptional suppressor, hairy, were over-represented in the regulatory regions of the down-regulated genes (15 out of 16) but not in the reference group (1 out of 7) (p<0.0001, CHI-Test). Furthermore, the expression level of hairy was also found to be significantly up-regulated in the hypoxia-selected flies. These results suggested that hairy, a key transcriptional suppressor, reduced the expression of the TCA cycle genes in hypoxia. Physical binding of hairy to the cis-regulatory regions of the candidate TCA cycle genes were confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation-PCR assay (ChIP-PCR) in Drosophila Kc cells that were treated with hypoxia. Furthermore, the hypoxia-induced suppression of TCA cycle genes was abolished in the hairy loss-of-function mutants, h1 or h1j3. Following these studies, two hairy-loss-of-function mutants were used to determine their survival rates in a relatively mild hypoxic condition (i.e., 6% of O2). We found that both hairy loss-of-function mutants exhibited much lower survival rate (p<0.0001, CHI-Test) as compared to controls, proving the role of hairy in hypoxia tolerance in flies (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Suppression of genes encoding glycolytic, TCA cycle enzymes and components of the respiratory chain complexes. A) Schematic illustration of the alterations in genes encoding glycolytic and TCA cycle enzymes (Green: down-regulated genes; Black: not significantly changed genes; Red, up-regulated genes). B) Cluster map of changes in genes encoding glycolytic enzymes in NF and AF larvae. C) Cluster map of changes in genes encoding TCA cycle enzymes in NF and AF larvae. D) Cluster map of changes in gene expression encoding components of respiratory chain complexes. Each cluster contained 9 hybridizations of NF and 8 hybridizations of AF samples. E) Summary of alterations in each respiratory chain complex measured in larvae. F) Comparison of gene expression changes in each respiratory chain complex between larvae and adult. (Adapted with permission from Zhou D et al., PLoS Genet 4:e1000221, copyright © 2008).

Figure 4.

Effect of the transcriptional suppressor, hairy, on TCA cycle gene expression and hypoxia tolerance. A) Genomic localization of hairy binding elements in the cis-regulatory region of genes encoding TCA cycle enzymes (Arrowheads, consensus hairy binding sites; Arrows, transcriptional start sites; Bold, down-regulated genes; Regular, not significantly changed or up-regulated genes). B) Significant up-regulation of hairy expression in hypoxia-selected AF populations (□: NF;  : AF) (**p<0.01). C) Abolished suppression of genes encoding TCA cycle enzymes in hairy loss-of-function mutants (■: AF; □: h1 mutant;

: AF) (**p<0.01). C) Abolished suppression of genes encoding TCA cycle enzymes in hairy loss-of-function mutants (■: AF; □: h1 mutant;  : h1j3 mutant). D) Significant reduction in hypoxia survival in hairy loss-of-function mutants (open bar: normoxia; gray bar: 6% O2) (**p<0.01). (Adapted with permission from Zhou D et al., PLoS Genet 4:e1000221, copyright © 2008).

: h1j3 mutant). D) Significant reduction in hypoxia survival in hairy loss-of-function mutants (open bar: normoxia; gray bar: 6% O2) (**p<0.01). (Adapted with permission from Zhou D et al., PLoS Genet 4:e1000221, copyright © 2008).

b2. Acute hypoxia and survival

This previous experiments focused on a long term type of hypoxia, occurring over many generations. However, from a clinical point of view, acute hypoxia (lasting min or hours) is also pertinent. In addition, since we have evidence that intermittent hypoxia is rather different from constant, we also made provisions to investigate both constant and acute stresses. Both of these frequently occur in disease states. For example, intermittent hypoxia (IH) is associated with obstructive sleep apnea, central hypoventilation syndrome and intermittent vascular occlusion in sickle cell anemia. Constant hypoxia (CH) is associated with pulmonary disease such as asthma, congenital heart disease with left to right shunt. Hypoxia can occur even under normal condition such as high altitude. Various studies, using rodents as animal models, have examined experimentally the effects of chronic CH and IH on specific tissues such as heart, brain, and kidneys (32–36) CH and IH are very different in their effect on growth, proliferation, generation of reactive O2 species, and neuronal injury (33, 37–40). Furthermore, in vivo studies have shown organ-specific phenotypic differences to low O2 such as hypertrophy in heart or decrease in myelination and N-Acetyl Aspartate/Creatine ratios in brain (36–38). In this study, we focus on gene expression changes associated with severe short term constant (CH) or intermittent hypoxia (IH) in adult flies. Our hypothesis was that CH induces different gene expression profile than IH in Drosophila and that these expression changes are important for inducing tolerance to short term hypoxia. Indeed, our microarray analysis has identified multiple gene families that are up- or down-regulated in response to acute CH or IH. Furthermore, we observed distinct responses to IH and CH in terms of gene expression that varied not only in the number of genes but also type of gene families. During CH, stress response genes (heat shock) were the most over-represented family whereas multidrug resistance genes were predominantly up-regulated during IH. With the use of P-elements and EP lines, we have also shown that these differentially expressed genes are important for the phenotype of survival. These data provide further clues about the mechanisms by which IH or CH lead to cell injury and morbidity or adaptation and survival.

While it is not clear at this stage from the results above on the acute or long term effect of hypoxia in flies whether the transcriptional changes are in fact a result of HIF-1α activation or other signaling pathways, our belief at present is that there is evidence that there are a number of switch mechanisms during hypoxia and these may vary from cell to cell, tissue to tissue and from species to species, just to name a few variables. Consider for example the metabolic switch that we have recently described, such as hairy, a target of Notch. Another example is the ADAR gene that we obtained from the forward genetic approach that we did several years ago and its ability to activate a switch mechanism that affects double-stranded pre-mRNAs. Our prediction is that a number of such switch mechanisms will be discovered soon with all the advanced technology that is and will be at our disposal in the next few years.

4. Why does it matter if flies are resistant to low O2? What about a proof of concept?

Like with any microarray analysis, the major question that emanates at the end of such an analysis is whether the genes that have altered expression have something to do with the phenotype of interest. Although hypoxia tolerance is likely to be a complex trait which involves coordinated action of many genes, individual gene expression profiling can provide clues about genes that control multigenic traits. However, it is likely that only some of the differentially expressed individual genes are directly responsible for hypoxia tolerance in the selected flies. To further identify the genes that functionally contributed to the tolerance of the lethal level of hypoxia (5% O2), we adopted a strategy that uses P-elements. These were first utilized for genes that were down-regulated in the microarray experiments (single P-element insertion Drosophila melanogaster lines). In addition, to further confirm that survival in these severe O2 conditions was related to the P-element insertion in these particular genes, we excised the P-element alleles of one gene, namely sec6, and found that the precise excision lines had less than 10% of eclosion in 5% O2, a level that is similar to naive controls. Therefore, the precise excision of these P-elements reversed the hypoxia tolerance phenotype. The sec6 gene encodes a protein that is homologous to a mammalian sec6 protein, and it is predicted to be involved in synaptic vesicle recycling (25). This presents the first evidence that this gene is involved in conferring hypoxia tolerance in Drosophila, possibly through regulation of neurotransmitter release.

Although the phenotype of hypoxia survival is, in all likelihood, complex and a number of genes may be acting in a coordinated way to affect hypoxia survival, what is surprising in our studies is that single gene alteration was able to affect the survival of flies to very low O2 environment! Clearly this does not indicate that multiple genes are not involved and that an even better survival might be achievable if a number of genes were altered at the same time. Our data indicate however that even single genes can be important in modulating this impressive phenotype and that a strategy like ours, which involved single P-element fly studies, has a chance in dissecting the importance of single genes in this phenotype of hypoxic survival.

That flies can become more tolerant or are naturally more tolerant to low O2 than mammals may not be surprising or, to some investigators, not relevant to human health. However, we believe that this can be a narrow view and that work in Drosophila can enhance our ability to understand biological normative processes and most probably human diseases. We will illustrate here with an example as a proof of concept.

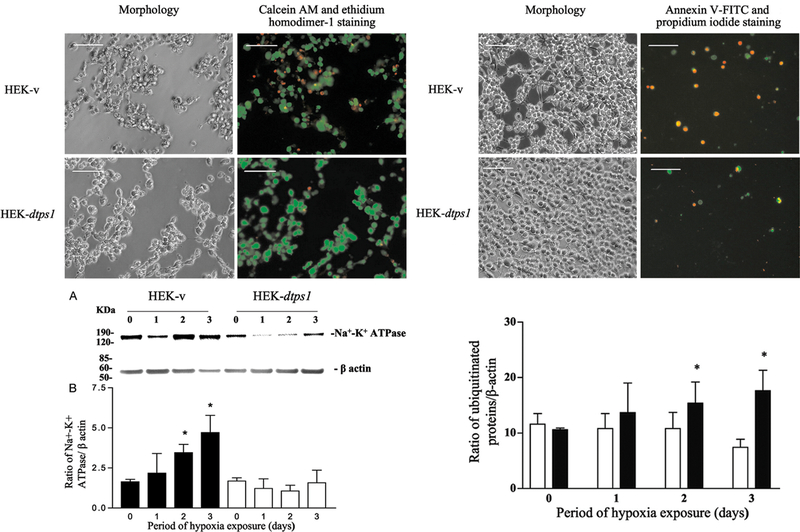

One of the important questions that we asked was whether trehalose, which is a glucose dimer, can play an important role in protecting flies against anoxic stress. We had discovered in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments that trehalose was present in abundance in Drosophila heads. We first cloned the gene for trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (tps1), which synthesizes trehalose, and examined the effect of tps1 overexpression or mutation on the resistance of Drosophila to anoxia (20, 21). Upon induction of tps1, trehalose increased, and this was associated with increased tolerance to anoxia. A transposable genetic element (p-element) inserted into an intron of the tps1 gene resulted in an embryonic lethal fly (19). To determine whether trehalose could protect against anoxic injury in mammalian cells, we transfected the Drosophilatps1 gene (dtps1) into human embryonic kidney cells (18). Glucose starvation in culture showed that HEK 293 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 (–) dtps1 (HEK-dtps1) did not metabolize intracellular trehalose and, interestingly, these cells accumulated intracellular trehalose during hypoxic exposure. In contrast to HEK 293 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 (–) (HEK-v), cells with trehalose (HEK-dtps1) were more resistant to low oxygen stress (1% O2; Figure 5). Insoluble proteins were three times more abundant in HEK-v than in HEK-dtps1 after 3 days of exposure to low O2. The amount of Na+–K+ ATPase present in the insoluble proteins dramatically increased in HEK-v cells after 2 and 3 days of exposure, whereas there was no significant change in HEK-dtps1 cells. Ubiquitinated proteins increased dramatically in HEK-v cells but not in HEK-dtps1 cells over the same period. Our results indicate that increased trehalose in mammalian cells following transfection by the Drosophila tps1 gene protects mammalian cells from hypoxic injury!

Figure 5.

Left upper panel: Cell viability assay after exposure to 1% O2 for 4 days. There were four times more dead cells in HEK-v than in HEK-dtps1. Right upper panel: Apoptosis assay of the cells after hypoxic treatment for 2 days. Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide stained on average 13.4 ± 3.2% and 6.4 ± 0.3% of the HEK-v cells but a much lower proportion of HEK-dtps1 cells (1.4 ± 0.4%, p < 0.001 and 0.3 ± 0.2%, p<0.0001). Left lower panel: A) Western signals of Na+-K+ ATPase and β-actin. B) The Na+-K+ ATPase amount present in the insoluble proteins fraction increases dramatically in HEK-v cells after 2 and 3 days of exposure (■: HEK-v; □: HEK-dtps1) (*p<0.05). Right lower panel: Intracellular trehalose reduces ubiquitinated proteins during hypoxia (■: HEK-v;□: HEK-dtps1) (*p<0.05). (Adapted with permission from Chen Q et al., J Biol Chem 278:49113–49118, copyright © 2003 by The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc.).

5. Hypoxia and Future Research

With the advances in technology, molecular biology and genomics and with the use of model systems, whether it is yeast, c-elegans, Drosophila or mice, research focusing on hypoxia has taken many twists and turns over the past 1–2 decades, as it always is, in basic and clinical research. One of the major questions that many investigators have tried to tackle in the past is that of O2 sensing. Extensive efforts have provided some answers but, by and large, many tissues and cell types seem to have their own specific important pathways and generalizations may not be very helpful (41).

Two other major areas have seen enormous growth in hypoxia research. One is related to cancer biology and the other to injury and repair mechanisms in various tissues, especially in brain, heart and kidneys. It is very clear now that hypoxia is part of the overall picture of tumor growth, metastasis, and treatment and many laboratories have focused their efforts on understanding the basis of the hypoxia modulation of cancer and on potential clinical trials. Injury and repair is also a major area now and the use of animal models, as we show in this review, has been an important addition to our armamentarium and our flexibility to impact on the field and be able to re-engineer susceptible cells into more resistant ones and help in either prevention or repair of tissues.

Acknowledgments

Statement of Financial Support: NIH - P01 HD 32573 and NIH R01 NS 037756 to GGH and AHA 0835188N to DZ.

Abbreviations:

- AF

Hypoxia-Adapted/selected Flies

- CH

Constant Hypoxia

- dADAR

pre-mRNA adenosine deaminase

- dMRP4

Drosophila homolog of the human multidrug resistance protein 4

- IH

Intermittent Hypoxia

- NF

Naïve control Flies

Contributor Information

Dan Zhou, Departments of Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, CA 92093.

DeeAnn W. Visk, Division of Biology, University of California, San Diego, CA 92093

Gabriel G. Haddad, Departments of Pediatrics and Neuroscience, University of California, San Diego, CA 92093, Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA 92123

References

- 1.Haddad GG, Jiang C 1993. Mechanisms of anoxia-induced depolarization in brainstem neurons: in vitro current and voltage clamp studies in the adult rat. Brain Res 625:261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banasiak KJ, Haddad GG 1998. Hypoxia-induced apoptosis: effect of hypoxic severity and role of p53 in neuronal cell death. Brain Res 797:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banasiak KJ, Cronin T, Haddad GG 1999. bcl-2 prolongs neuronal survival during hypoxia-induced apoptosis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 72:214–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banasiak KJ, Xia Y, Haddad GG 2000. Mechanisms underlying hypoxia-induced neuronal apoptosis. Prog Neurobiol 62:215–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bier E 2005. Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nat Rev Genet 6:9–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farahani R, Haddad GG 2003. Understanding the molecular responses to hypoxia using Drosophila as a genetic model. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 135:221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haddad GG 2006. Tolerance to low O2: lessons from invertebrate genetic models. Exp Physiol 91:277–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodmer R 1993. The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila. Development 118:719–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azpiazu N, Frasch M 1993. tinman and bagpipe: two homeo box genes that determine cell fates in the dorsal mesoderm of Drosophila. Genes Dev 7:1325–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bier E, Bodmer R 2004. Drosophila, an emerging model for cardiac disease. Gene 342:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caudy AA, Myers M, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM 2002. Fragile X-related protein and VIG associate with the RNA interference machinery. Genes Dev 16:2491–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizuka A, Siomi MC, Siomi H 2002. A Drosophila fragile X protein interacts with components of RNAi and ribosomal proteins. Genes Dev 16:2497–2508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cauchi RJ, van den Heuvel M 2006. The fly as a model for neurodegenerative diseases: is it worth the jump? Neurodegener Dis 3:338–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang S, Bray SM, Li Z, Zarnescu DC, He C, Jin P, Warren ST 2008. Identification of small molecules rescuing fragile X syndrome phenotypes in Drosophila. Nat Chem Biol 4:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas RM, Haddad GG 2003. Genetic models in applied physiology: invited review: effect of oxygen deprivation on cell cycle activity: a profile of delay and arrest. J Appl Physiol 94:2068–2083 discussion 2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddad GG, Sun Y, Wyman RJ, Xu T 1997. Genetic basis of tolerance to O2 deprivation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:10809–10812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddad GG, Wyman RJ, Mohsenin A, Sun Y, Krishnan SN 1997. Behavioral and Electrophysiologic Responses of Drosophila melanogaster to Prolonged Periods of Anoxia. J Insect Physiol 43:203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Rio DC, Haddad GG, Ma E 2004. Regulatory role of dADAR in ROS metabolism in Drosophila CNS. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 131:93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Q, Behar KL, Xu T, Fan C, Haddad GG 2003. Expression of Drosophila trehalose-phosphate synthase in HEK-293 cells increases hypoxia tolerance. J Biol Chem 278:49113–49118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Q, Haddad GG 2004. Role of trehalose phosphate synthase and trehalose during hypoxia: from flies to mammals. J Exp Biol 207:3125–3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Q, Ma E, Behar KL, Xu T, Haddad GG 2002. Role of trehalose phosphate synthase in anoxia tolerance and development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem 277:3274–3279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H, Haddad GG 2007. Drosophila dMRP4 regulates responsiveness to O2 deprivation and development under hypoxia. Physiol Genomics 29:260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma E, Gu XQ, Wu X, Xu T, Haddad GG 2001. Mutation in pre-mRNA adenosine deaminase markedly attenuates neuronal tolerance to O2 deprivation in Drosophila melanogaster. J Clin Invest 107:685–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia S, Yang J, Su Y, Qian J, Ma E, Haddad GG 2005. Identification of new targets of Drosophila pre-mRNA adenosine deaminase. Physiol Genomics 20:195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou D, Xue J, Chen J, Morcillo P, Lambert JD, White KP, Haddad GG 2007. Experimental selection for Drosophila survival in extremely low O2 environment. PLoS One 2:e490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou D, Xue J, Lai JC, Schork NJ, White KP, Haddad GG 2008. Mechanisms underlying hypoxia tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster: hairy as a metabolic switch. PLoS Genet 4:e1000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma E, Xu T, Haddad GG 1999. Gene regulation by O2 deprivation: an anoxia-regulated novel gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 63:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma E, Tucker MC, Chen Q, Haddad GG 2002. Developmental expression and enzymatic activity of pre-mRNA deaminase in Drosophila melanogaster. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 102:100–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochachka PW 1986. Defense strategies against hypoxia and hypothermia. Science 231:234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochachka PW, Clark CM, Brown WD, Stanley C, Stone CK, Nickles RJ, Zhu GG, Allen PS, Holden JE 1994. The brain at high altitude: hypometabolism as a defense against chronic hypoxia? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14:671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hochachka PW, Dunn JF 1983. Metabolic arrest: the most effective means of protecting tissues against hypoxia. Prog Clin Biol Res 136:297–309 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iacobas DA, Fan C, Iacobas S, Spray DC, Haddad GG 2006. Transcriptomic changes in developing kidney exposed to chronic hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 349:329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou D, Wang J, Zapala MA, Xue J, Schork NJ, Haddad GG 2008. Gene expression in mouse brain following chronic hypoxia: role of sarcospan in glial cell death. Physiol Genomics 32:370–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farahani R, Kanaan A, Gavrialov O, Brunnert S, Douglas RM, Morcillo P, Haddad GG 2008. Differential effects of chronic intermittent and chronic constant hypoxia on postnatal growth and development. Pediatr Pulmonol 43:20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iacobas DA, Fan C, Iacobas S, Haddad GG 2008. Integrated transcriptomic response to cardiac chronic hypoxia: translation regulators and response to stress in cell survival. Funct Integr Genomics 8:265–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan C, Iacobas DA, Zhou D, Chen Q, Lai JK, Gavrialov O, Haddad GG 2005. Gene expression and phenotypic characterization of mouse heart after chronic constant or intermittent hypoxia. Physiol Genomics 22:292–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanaan A, Farahani R, Douglas RM, Lamanna JC, Haddad GG 2006. Effect of chronic continuous or intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation on cerebral capillary density and myelination. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290:R1105–R1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Douglas RM, Miyasaka N, Takahashi K, Latuszek-Barrantes A, Haddad GG, Hetherington HP 2007. Chronic intermittent but not constant hypoxia decreases NAA/Cr ratios in neonatal mouse hippocampus and thalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292:R1254–R1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandel NS, Budinger GR 2007. The cellular basis for diverse responses to oxygen. Free Radic Biol Med 42:165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dewhirst MW, Cao Y, Moeller B 2008. Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nat Rev Cancer 8:425–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haddad GG 1997. K+ ions and channels: mechanisms of sensing O2 deprivation in central neurons. Kidney Int 51:467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]