A multiple approach–based analysis elucidates mechanisms underlying temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition.

Abstract

Temperature sensitivity (Q10) of soil organic matter (SOM) decomposition is a crucial parameter for predicting the fate of soil carbon (C) under global warming. However, our understanding of its regulatory mechanisms remains inadequate, which constrains its accurate parameterization in Earth system models and induces large uncertainties in predicting terrestrial C-climate feedback. Here, we conducted a long-term laboratory incubation combined with a two-pool model and manipulative experiments to examine potential mechanisms underlying the depth-associated Q10 variations in active and slow soil C pools. We found that lower microbial abundance and stronger aggregate protection were coexisting mechanisms underlying the lower Q10 in the subsoil. Of them, microbial communities were the main determinant of Q10 in the active pool, whereas aggregate protection exerted more important control in the slow pool. These results highlight the crucial role of soil C stabilization mechanisms in regulating temperature response of SOM decomposition, potentially attenuating the terrestrial C-climate feedback.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, approximately 2300 Pg (1 Pg = 1015 g) carbon (C) is stored in the top 3 m of soils, of which more than 70% is distributed in deep horizons below 20 cm (1). Deep soil C is characterized by high stability over long time scales, because the rate of soil organic matter (SOM) decomposition usually decreases with soil depth (2). Similar to many other biochemical reactions, the decomposition of SOM is temperature dependent (3). Because of this point, global warming is expected to promote carbon dioxide (CO2) release from both the topsoil and the subsoil, thereby triggering a potential positive feedback (4, 5). However, large uncertainties remain in the magnitude of this C-climate feedback, partly due to the inaccurate parameterization of the temperature sensitivity (Q10) of SOM decomposition in different soil depths and C pools in Earth system models (ESMs) (3, 6). It has been estimated that the current use of a globally constant Q10 value in most models underestimates the magnitude of C-climate feedback by 25% compared to incorporating the spatially heterogeneous Q10 values into models (7). Therefore, a deeper understanding of the fundamental mechanisms regulating Q10 is pivotal for accurately predicting soil C dynamics and reducing model uncertainties in forecasting terrestrial C-climate feedback.

Historically, SOM quality had been recognized as the major determinant of Q10. On the basis of enzyme kinetic theory, “carbon-quality temperature” hypothesis predicts that the decomposition of low-quality substrates in the subsoil requires high activation energy and is thus more sensitive to temperature changes (8, 9). However, several emergent conceptual frameworks have challenged the perceived importance of soil C quality in governing the decomposition of SOM and its responses to warming, and argued that processes controlling substrate accessibility (e.g., SOM protection, spatial disconnection, and enzyme diffusion) are also critically important (10–13). Moreover, microbial properties (e.g., microbial abundance, community composition, and enzyme productions) and the existence of energetic barriers to microorganisms regulate SOM decomposition and Q10 as well (2, 10, 14, 15). Despite the theoretical predictions of an important role for these factors, direct evidence for the effects of SOM protection and microbial communities on Q10 is scarce (16), which, in turn, limits the accurate parameterization of Q10 in ESMs. The soil profile provides an ideal natural gradient for exploring the relative contribution of different mechanisms underlying Q10 due to vertical variations in substrate quality and environmental and microbial controls over SOM decomposition (9, 17, 18). Moreover, manipulative experiments such as aggregate disruption experiments (19) and microorganism reciprocal transplant experiments (20), combined with laboratory culture, offer the possibility to explore the effects of aggregate protection and microbial communities on Q10, respectively. However, these approaches have not been adequately applied in disentangling the complex mechanisms regulating Q10 between soil depths.

It is widely recognized that the large heterogeneity of SOM decomposition and its response to warming exists not only between soil depths but also within the composition of SOM itself (16, 21, 22). SOM is considered as a heterogeneous mixture consisting of pools with different turnover times, which is also the premise of classic soil C models such as Century (23) and RothC (24). It has been assumed that the active C pool, persisting for hours to weeks, is composed mainly of chemically labile and unprotected compounds, whereas the slow C pool could persist for decades to centuries due to the physicochemical and biological constraints on decomposition (13). These variations in substrate quality and abiotic and biotic regulators between C pools imply that their responses to climate warming and the associated mechanisms may also differ (12). Despite this recognition, current models assume equal Q10 value for all C pools (3). The assumption of a single Q10 value may obscure the responses of soil C pool to climate warming, especially for the slow C pool, whose temperature response cannot be well captured from short-term incubation experiments (21, 25). With the development of a data-model fusion technology, Bayesian probabilistic inversion, it is possible to estimate Q10 values for different soil C pools through the combination of long-term incubations and two-pool models (26). Nonetheless, limited studies have adopted this approach to explore potential mechanisms regulating Q10 for different soil C pools.

This study aimed to address the following three questions: (i) Are Q10 values for bulk soil, active C pool, and slow C pool different between the topsoil and the subsoil? (ii) What are the regulatory mechanisms underlying the Q10 difference between soil depths? (iii) Are the regulatory mechanisms different between the two C pools? To answer these questions, topsoil samples from 0 to 10 cm depth and subsoil samples from 30 to 50 cm depth were collected from three alpine meadow sites on the Tibetan Plateau (fig. S1). On the basis of these samples, we conducted a 330-day incubation experiment, in combination with three methods (bulk soil Q10 by average decomposition rate, Q10 values for different respired soil C fractions through the Q10-q method, and active and slow pool Q10 by the two-pool model), to estimate the Q10 values of various SOM components for the two soil depths. Soil properties including substrate quality, SOM protection, and microbial characteristics were then quantified to explore the determinants of Q10. We further performed two manipulative experiments (i.e., aggregate disruption experiment and microorganism reciprocal transplant experiment) to examine the effects of aggregate protection and microbial communities on Q10 in different C pools.

RESULTS

Differences in Q10 values between soil depths

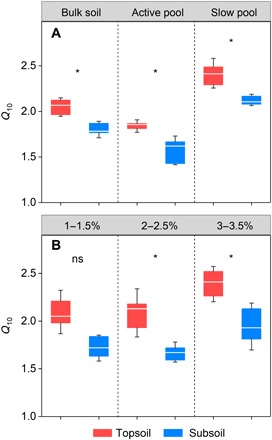

Bulk soil Q10 in the topsoil was estimated at 2.1 on average, significantly higher than the value (1.8) in the subsoil (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A). No significant interactions between site and depth were observed, demonstrating that the depth effect on Q10 was independent of the sampling site (P = 0.28; table S1). To further explore Q10 for various SOM components, we adopted the Q10-q method to evaluate Q10 for three soil C fractions (i.e., 1 to 1.5%, 2 to 2.5%, and 3 to 3.5% of cumulative respired soil C), which represent a gradient of decreasing substrate lability. Similarly, the topsoil Q10 was significantly higher than the subsoil for 2 to 2.5% and 3 to 3.5% of cumulative respired soil C (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B), without interaction effects (P = 0.20 and 0.50, respectively; table S1). No significant difference was detected in the Q10 value of 1 to 1.5% of cumulative respired soil C between soil depths (P = 0.05; table S1). In addition, Q10 estimated from the two-pool model also showed significantly lower values in the subsoil for both active pool and slow pool (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A), with no site × depth interaction (P = 0.31 and 0.26 for active pool and slow pool, respectively; table S1).

Fig. 1. Q10 values for various SOM components in the topsoil and subsoil.

(A) Q10 for bulk soil, active pool, and slow pool. (B) Q10 for three cumulative respired soil C fractions. The ends of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines inside each box and the whiskers show the median and the SD, respectively (n = 9). *P < 0.05, significant difference between the topsoil and the subsoil; ns, no significant difference.

Determinants of the Q10 difference between soil depths

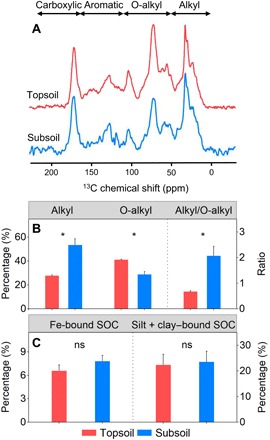

To explore determinants of the Q10 difference between soil depths, we analyzed four types of variables associated with Q10, including substrate quality, SOM association with minerals, SOM protection by aggregates, and microbial communities, and compared them between the two soil depths. Of these variables, substrate quality revealed by SOM composition differed between the topsoil and the subsoil. Specifically, the intensity of O-alkyl C acquired from solid-state 13C CPMAS (cross polarization with magic-angle spinning) NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) was higher in the topsoil (41%) than in the subsoil (29%) (P < 0.01; Fig. 2, A and B), whereas the contribution of alkyl C was significantly higher in the subsoil (53%) than in the topsoil (28%) (P < 0.01; Fig. 2, A and B). The calculated alkyl/O-alkyl ratio was thus significantly higher in the subsoil (P < 0.01; Fig. 2B), indicating more recalcitrant SOM in deep soils. Consequently, on the basis of the “carbon-quality temperature” hypothesis, the poorer substrate quality could not be responsible for the lower Q10 in the subsoil.

Fig. 2. Comparison of SOM composition and mineral protection between the topsoil and the subsoil.

(A) 13C CPMAS NMR spectra. Chemical shifts of 0 to 50, 50 to 110, 110 to 165, and 165 to 220 parts per million (ppm) represent alkyl C, O-alkyl C, aromatic C, and carboxylic C, respectively. (B) Percentage of alkyl C and O-alkyl C relative to total SOC and ratio of the two SOM compositions. (C) Percentage of Fe-bound SOC and silt + clay–bound SOC relative to total SOC. Error bars denote SE (n = 9). *P < 0.01, significant difference between the topsoil and the subsoil. ns, no significant difference.

We then measured the proportion of soil organic carbon (SOC) associated with Fe to total SOC (i.e., Fe-bound SOC) to quantify SOM protection by minerals. The results revealed no significant difference in the Fe-bound SOC between the topsoil and the subsoil (P = 0.17; Fig. 2C). In consistence, the proportion of SOC associated with silt + clay (<53 μm) acquired by the wet-sieving technique did not show significant difference (P = 0.83; Fig. 2C), jointly indicating that SOM protection by minerals might be less responsible for the Q10 difference between soil depths. However, SOM protection by aggregates, as determined by the same technique, differed between the two soil depths. Compared with the topsoil, the proportion of SOC distribution in the subsoil was lower in macroaggregates (250 to 2000 μm, 44% versus 63%, P < 0.01; Fig. 3A) but higher in microaggregates (53 to 250 μm, 32% versus 15%, P < 0.01; Fig. 3B). Moreover, as revealed by linear regression analyses, these differences in aggregate protection were associated with the Q10 differences between soil depths. Bulk soil Q10, active pool Q10, and slow pool Q10 all increased with the proportion of SOC distributed in macroaggregates (Fig. 3, A, C, and E) but decreased with the proportion in microaggregates (Fig. 3, B, D, and F).

Fig. 3. Relationships between Q10 and C distribution in aggregates.

(A and B) Bulk soil Q10 with macro and micro. (C and D) Active pool Q10 with macro and micro. (E and F) Slow pool Q10 with macro and micro. Macro refers to the percentage of soil C stored in macroaggregates (250 to 2000 μm), and micro denotes the percentage in microaggregates (53 to 250 μm). Red circles represent samples in the topsoil (n = 9), and blue circles represent samples in the subsoil (n = 9). r2 is the proportion of variance explained. The insets show the depth-associated variations of C distribution in macroaggregates and microaggregates, respectively. Error bars denote SE (n = 9). *P < 0.01, significant difference between the two soil depths.

Microbial communities, as determined through phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis, also differed between the topsoil and the subsoil. The abundances of the microbial groups, including total PLFAs, bacterial PLFAs, and fungal PLFAs, were all higher in the topsoil than in the subsoil (P < 0.01; table S2). The community structure was different in certain aspects, with significantly higher fungal/bacterial (F/B) ratio (P < 0.05) and relative abundance of fungal PLFAs (fungal PLFAs/total PLFAs, P < 0.01) in the topsoil (table S2), while there was no difference in the relative abundance of bacterial PLFAs (bacterial PLFAs/total PLFAs) between the two depths (P = 0.10; table S2). These variations in microbial communities also contributed to the Q10 differences: Bulk soil Q10, active pool Q10, and slow pool Q10 were all positively associated with the relative abundance of fungal PLFAs (Fig. 4, A to C).

Fig. 4. Relationships between Q10 and fungal PLFAs.

(A) Bulk soil Q10. (B) Active pool Q10. (C) Slow pool Q10. Fungal PLFAs refer to the relative abundance of fungi (fungal PLFAs/total PLFAs). Red circles represent samples in the topsoil (n = 9), and blue circles represent samples in the subsoil (n = 9). r2 is the proportion of variance explained. The inset shows the comparison of relative abundance of fungal PLFAs between the topsoil and the subsoil. *P < 0.01. Error bars are SE (n = 9).

Mechanisms of depth-associated variations in Q10 in various C pools

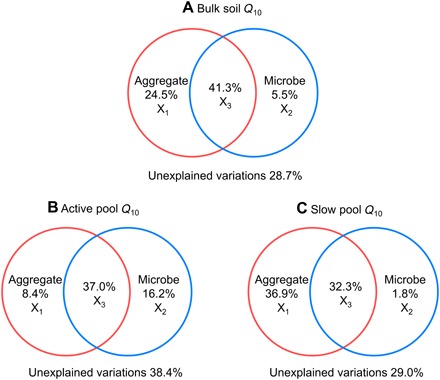

To test whether the underlying mechanisms of depth-associated variations in Q10 were C pool dependent, we conducted variation partitioning analyses for the active and slow C pools. During these analyses, we incorporated aggregate protection and microbial communities, which exerted significant controls over Q10 (Figs. 3 and 4). The results demonstrated that Q10 variations in the bulk soil and slow pool were primarily explained by aggregate protection, with the pure effects being 24.5% (Fig. 5A) and 36.9% (Fig. 5C), respectively. The Q10 variations in the active pool, however, were mainly explained by microbial communities, whose pure effect was 16.2% (Fig. 5B). These results demonstrated that microbial communities governed Q10 in the active pool, while aggregate protection governed Q10 in the slow pool.

Fig. 5. Variation partitioning analyses for Q10 in various SOM components.

(A) Bulk soil Q10. (B) Active pool Q10. (C) Slow pool Q10. The variation is partitioned to the following fractions: pure effect of aggregate protection (X1), pure effect of microbial communities (X2), joint effects of aggregate protection and microbial communities (X3), and unexplained variations. Aggregate protection includes the percentage of soil C stored in macroaggregates (250 to 2000 μm) and microaggregates (53 to 250 μm). Microbial communities refer to the relative abundance of fungal PLFAs.

The different underlying mechanisms of Q10 between the two C pools were confirmed by the microorganism reciprocal transplant experiment and aggregate disruption experiment. The former experiment showed that, in the active pool, inoculating the topsoil with the subsoil microorganism (away inoculum) significantly decreased Q10 compared with its own inoculum (P < 0.01; fig. S2A), whereas inoculating the subsoil with the topsoil microorganism (away inoculum) resulted in a significantly higher Q10 (P < 0.01; fig. S2A). Consequently, △Q10 (i.e., Q10 topsoil − Q10 subsoil) was significantly lower for the treatment of away inoculum in the active pool (P < 0.01; Fig. 6A). However, in the slow pool, no significant difference was detected between the two inoculums in both the topsoil and the subsoil (P = 0.88 and 0.21, respectively; fig. S2B), and thus, no change was observed for △Q10 in this pool (P = 0.20; Fig. 6A). In contrast, the later experiment demonstrated that the SOM protection by aggregates mainly affected Q10 in the slow pool. The removal of aggregate protection by crushing resulted in a significantly declined △Q10 in the slow pool (P < 0.01) but had no effect in the active pool (P = 0.21; Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. △Q10 in active and slow pools derived from two manipulative experiments.

(A) Microorganism reciprocal transplant. (B) Aggregate disruption. △Q10 is the Q10 difference between the topsoil and the subsoil, with a positive value representing larger Q10 in the topsoil and a negative value representing larger Q10 in the subsoil. Error bars denote SE (n = 9). *P < 0.01, significant difference between control and treatment. ns, no significant difference.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that SOM decomposition in the topsoil was more sensitive to warming than in the subsoil. This significant difference could be due to the following two reasons. First, the stronger SOM protection by aggregates in the subsoil could attenuate Q10. Aggregate protection exerts important control over the stabilization of SOM (27), and it has been reported that small sizes of aggregates need more energy to be disrupted (11). That is to say, the degree of protection increases with the decline in aggregate sizes and would be stronger in microaggregates (27). In our study, a higher proportion of C stored in microaggregates in the subsoil compared with the topsoil indicated that aggregate protection was stronger in the subsoil, which further resulted in a lower Q10 value through the following two aspects. On the one hand, SOM is occluded in the interior of microaggregates, inducing spatial disconnection between substrates and enzymes, and thus protecting SOM from microbial decomposition (27). On the other hand, the small sizes of microaggregates could restrict the diffusion of oxygen (11), which limits the activity of microorganisms and results in low Q10 (28). Overall, the determining role of SOM protection by aggregates observed here, together with previous proposals (3, 10), jointly demonstrates the importance of aggregate protection in governing the response of SOM decomposition to global warming.

Second, variations in microbial communities between soil depths could lead to the Q10 difference. Microorganisms are addressed to play key roles in regulating the terrestrial C cycle, mediating not only the rate of SOM decomposition but also its responses to warming (14). In our study, the lower microbial abundance in the subsoil (table S2) that resulted from the alterations in soil resource availability (e.g., the decline in soil C and nitrogen; table S3) might constrain SOM decomposition even under high temperature and thus attenuate Q10 (15). Moreover, microbial community composition would also affect Q10. It has been reported that fungi are the dominant decomposers of recalcitrant substrates (29). Because the decomposition of these low-quality substrates requires greater activation energy (8), the shift in microbial community composition with decreasing proportion of fungi with soil depth may contribute to the lower Q10 in the subsoil (30). These deductions were further confirmed by the microorganism reciprocal transplant experiment: By applying inoculums with high microbial abundance and fungi proportion to the subsoil, Q10 significantly increased, while applying inoculums with low microbial abundance and fungi proportion to the topsoil significantly decreased Q10 (fig. S2A). In addition to the variations in microbial communities, the activities of subsoil microorganisms might not be sustained by enough energy due to the lack of fresh substrates (2, 31, 32), which would further attenuate Q10 in the subsoil (33).

Our results also demonstrated that the Q10 variation in the active pool was primarily mediated by microbial communities, whereas the Q10 variation in the slow pool was mainly explained by aggregate protection. The difference in the underlying mechanisms between C pools could be largely due to their distinct physicochemical and biological properties. To be specific, most compounds in the active pool are unprotected and thus more accessible to microorganisms (13). The high substrate availability indicates that the decomposition of these unprotected SOM and their responses to warming are mainly related to microbial communities (27), especially for the subsoil, where low microbial abundance and fungal proportions could limit the decomposition activity under a warming scenario (15). By contrast, in the slow pool, most compounds are preserved with the protection of soil minerals and aggregates (11). Even in the presence of high-quality substrates and a competent microbial community, aggregates could prevent the contact of substrates and microorganisms and constrain the responses of SOM decomposition to warming (3, 10). Consequently, the level of SOM protection by aggregates becomes the major determinant of Q10 in the slow pool. Nevertheless, other properties might also be distinct among soil C pools and thus function differently in regulating Q10 of various SOM components, such as the dynamics of enzyme pools (34) and the energetic signatures of substrates (35), which need to be addressed in future studies.

Although our study provided empirical evidence for the mechanisms underlying Q10, there are still some limitations. First, in addition to the mechanisms considered in this study, other biotic and abiotic controls such as the energetic constraints of microorganisms (2, 31, 32, 35), the dynamics of enzyme pools and their catalytic power (34), the spatial separation of substrates (36), and the diffusion of enzymes and oxygen (11) could also regulate SOM decomposition and its temperature response. Extending studies incorporating these factors are deserved to gain further understanding on this issue. Second, despite a widely used sterilization technique with limited effects on soil physical properties, γ-irradiation would affect soil chemical properties through the release of labile C (37). Moreover, noncellular processes, which have been considered important in CO2 production (38, 39), were not determined in the current sterilization experiment. Future studies should thus aim to better differentiate the effects of substrates and microorganisms and also evaluate the contribution of noncellular processes to soil C release and their temperature responses. Third, the Q10 values of different soil C pools were estimated from a first-order kinetic model without representing other controls on SOC dynamics, such as microbial growth, activities, turnover, and C use efficiency (40, 41); enzyme activities and dynamics (34, 42); organic matter–mineral interactions (6); and hydrologically driven diffusion of substrates or enzymes (43). In view of the simple assumption about soil C turnover in current models, uncertainties might exist in model estimations. Hence, future studies should improve model structure to better reflect the mechanisms of soil C stabilization (6) and also measure Q10 of different soil C pools directly to provide benchmark for model development.

In summary, through a multiple approach–based analysis, we observed that, across soil depths, lower microbial abundance and stronger SOM protection by aggregates are two coexisting mechanisms responsible for the lower Q10 in the subsoil. We also found that the underlying mechanisms of Q10 were different between the active and slow pools, as microbial communities dominated in the active pool, whereas aggregate protection was more important in the slow pool. Given that the slow C pool is the largest component of SOM with a longer turnover time, SOM protection via microaggregates could be the key mechanism that regulates the long-term response of SOM decomposition to global warming. Overall, these findings imply that the existence of soil C stabilization mechanisms could reduce the effect of climate warming on SOM decomposition, especially for the large deep and slow C pools, thereby attenuating the predicted terrestrial C-climate feedback.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description and soil sampling

We collected soil samples from three alpine meadow sites on the Tibetan Plateau, China, where substantial quantities of soil organic C (15.3 Pg) were stored in the top 3 m (44). In the past decades, mean annual temperature on the plateau increased at a rate about twice that of global warming (45). The high rate of climate warming, together with the high Q10 on the plateau (46), could induce potential positive C-climate feedback in this unique geographic region. Moreover, because of the detected differences in substrate quality, environmental constraints, and microbial properties among soil depths (17), there might be considerable differences in Q10 through soil profile. To test this possibility, we selected three sampling sites (Halejing, Xihetai, and Zhagamu) on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau (fig. S1A) and examined Q10 in different soil depths and various soil C components, as well as the associated mechanisms.

The sites are situated at latitudes of 37.02°N to 37.61°N and longitudes of 100.11°E to 101.24°E, with an elevation of 3200 to 3400 m. The mean annual temperature varies from 0.12° to 2.20°C, and the mean annual precipitation ranges from 340 to 378 mm. The vegetation type belongs to alpine meadow, characterized by the dominant species of Kobresia pygmaea in Halejing and Zhagamu, and Kobresia humilis in Xihetai. The soil type at the three study sites is Cambisol according to the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (46). Cambisols are widespread not only on the Tibetan Plateau but also worldwide (47), accounting for ~38% of the Tibetan Plateau and ~11% of the global land surface. Soil physicochemical properties at these sites are given in table S3.

We conducted soil sampling in July and August 2014 (44). At each sampling site, we set up a 10 m × 10 m square plot and excavated three replicate soil pits at two corners and the center along a diagonal line (fig. S1B). We then collected topsoil at depths of 0 to 10 cm and subsoil at depths of 30 to 50 cm (fig. S1C). Soils from each depth were divided into two subsamples: one of which was passed through a 2-mm sieve and stored at −20°C to determine SOM composition and microbial communities; the other set was air-dried and processed for measurements of other physicochemical properties.

Experimental design

To examine the Q10 difference between soil depths and the associated mechanisms, we established two manipulative experiments based on 330-day incubations at 10° and 20°C: One was conducted to compare Q10 in the topsoil and subsoil, and also to test the effects of aggregate protection through the uncrushed (control) and crushed (remove aggregate protection) soils (termed “aggregate disruption experiment”). The other was performed to examine the depth difference in microbial controls by inoculating soils with active microorganism from away (collected in the other depth) and own (the same depth) (termed “microorganism reciprocal transplant experiment”).

In the aggregate disruption experiment, we compared Q10 between the topsoil and the subsoil and then examined the effects of aggregate protection on Q10. The treatments included uncrushed (control) and crushed soil samples. For the crushed treatment, air-dried soil samples were crushed for 1 min by a ball mill to disrupt aggregates and remove aggregate protection (19). Together, a 3 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 factorial experiment was conducted corresponding to three study sites, two soil depths, two levels of aggregate disruption, two incubation temperatures, and three replicates. For each of these treatments, 10 g of air-dried topsoil and 20 g of air-dried subsoil from each replicate were evenly distributed into 250 ml of airtight amber jars and incubated at both 10° and 20°C for 330 days (fig. S1D). Soil moisture was adjusted to 60% of water holding capacity (46). The rate of CO2 release was determined on the basis of the changes in headspace CO2 concentration during the incubation interval (17) using an infrared gas analyzer (EGM-5; PP Systems, Haverhill, MA, USA). The measurements were taken every 1 to 4 days for the first 3 weeks and then 1 to 2 weeks for 3 months, followed by 1 to 2 months for the rest of the incubation. It should be noted that the CO2 production from the uncrushed (control) soils was also used to explore the difference in Q10 between soil depths.

In the microorganism reciprocal transplant experiment, we explored whether microorganisms were functionally different between soil depths (20). This experiment was conducted by applying two microbial inoculums (derived from topsoil and subsoil) to both sterilized topsoil and subsoil. Specifically, soil samples were sterilized using γ-irradiation (60Co) at a dose of 30 kGy (37). The sterilized soil was then divided into two subsamples, receiving the inoculum derived from itself (own) and from the other corresponding depth (away), respectively; the former treatment (own) was treated as control. In total, 72 microcosms (3 sites × 2 soil depths × 2 inoculums × 2 temperatures × 3 replicates) were constructed. Inoculums from each soil depth were made by adding 1 g of dry weight fresh soil to 100 ml of sterilized deionized water. Then, the inoculum was shaken at 150 rpm for 0.5 hour and filtered through a Whatman GF/C filter. Inoculum (0.4 ml) was applied to per gram soil. The procedure of subsequent CO2 measurement was the same as the first experiment.

Calculation of Q10 values

We adopted three methods to calculate Q10 values for bulk soil and various SOM components. First, Q10 for bulk soil was calculated according to the decomposition rate at two incubation temperatures

| (1) |

where Rw and Rc denote the average rate of SOM decomposition at the warmer and colder temperature (mg CO2-C g−1 SOC day−1), respectively. Tw and Tc represent the warmer and colder temperature (°C). Q10 obtained by this method was referred to as bulk soil Q10.

Second, the Q10-q method, which is based on the measured cumulative percentage of soil C respired during incubation, was applied to calculate the Q10 values of different SOM fractions (22)

| (2) |

where tc and tw are the time needed to decompose a given soil C fraction at the colder and warmer temperature (day), respectively. Tw and Tc denote the warmer and colder temperature (°C). In this study, we chose the upper limit of soil C fraction according to the lowest cumulative percentage of respired C at 10°C (3.9%; fig. S3), which was within the range of previous incubations (0.4 to 17.0%) based on the same temperature and the approximate duration (48, 49). According to a previous study (16), we then set the size of the fractions as 0.5% of total soil C and estimated Q10 values for three fractions of soil C (i.e., 1 to 1.5%, 2 to 2.5%, and 3 to 3.5% of cumulative respired soil C), which represent a gradient of decreasing substrate lability.

Last, we used a two-pool (that is, active and slow pools with different turnover times) model to estimate Q10 for each C pool using data from our 330-day incubation experiment. The two-pool model performed well in simulating the soil C flux (fig. S4) and was applied to each sample at the two temperatures as follows (26)

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where R(t) is the measured decomposition rate at time t (mg CO2-C g−1 SOC day−1). Ctot denotes the initial SOC content (i.e., 1000 mg C g−1 SOC), k1 and k2 are the decay rates of active and slow pool (day−1), and f1 and f2 denote the fractions of the active pool and slow pool. and represent Q10 in the active pool and slow pool. ki(Tw) and ki(Tc) are the decay rates at the warmer (Tw) and colder (Tc) temperature, respectively. Before modeling, the prior range of the five parameters (k1 and k2 at 10°C, , , and f1; table S4) was set on the basis of previous studies (17, 50) and then determined by a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach as follows (26): Probabilistic inversion approach based on Bayes’ theorem (Eq. 6) was applied to optimize parameters (θ) in the model. In this approach, the posterior probability density function (PDF) P(θ|Z) was acquired from the prior knowledge of parameters and the information of incubation data, represented by a prior PDF P(θ) and a likelihood function P(Z|θ), respectively

| (6) |

To calculate the likelihood function P(Z|θ), we assumed that errors between modeled and observed values followed a multivariate Gaussian distribution with a zero mean

| (7) |

where Zi(t) and Xi(t) denote the measured and modeled data, and σi(t) represents the SD of the measurements. Metropolis-Hastings (M-H) algorithm, an MCMC technique, was used to complete the construction of P(θ|Z) of parameters (51, 52).

Measurements of abiotic and biotic variables associated with Q10

We determined four types of variables, including substrate quality, SOM association with minerals, SOM protection by aggregates, and microbial communities, to explore potential mechanisms responsible for the Q10 difference between the two soil depths. Specifically, to determine substrate quality, SOM composition was investigated by solid-state 13C CPMAS NMR. Having been treated with 10% hydrofluoric acid (HF) repeatedly (53), soil samples were rinsed with deionized water and then freeze-dried. Approximately 100 mg of HF-treated samples was measured on an AVANCE III 400 WB spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) at 100.62 MHz. The spectrometer was equipped with a 4-mm CPMAS probe, and the parameters were set with a spinning rate of 8 kHz, a contact time of 2 ms, and a recycle delay of 6 s. We then used MestReNova 9.0 (Mestrelab Research S.L., Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain) to integrate the spectra into the following chemical shift regions and acquire the relative intensity of each region: alkyl C [0 to 50 parts per million (ppm)], O-alkyl C (50 to 110 ppm), aromatic C (110 to 165 ppm), and carboxylic C (165 to 220 ppm) (54).

To quantify SOM protection by minerals, Fe-bound SOC, which directly reflects the proportion of SOC associated with reactive Fe, was determined on the basis of the citrate-bicarbonate-dithionite (CBD) method (55). Briefly, in the reduction treatment, a solution containing trisodium citrate and sodium bicarbonate was added to 0.25 g of soil and heated to 80°C by water bath. A reducing agent, sodium dithionite, was then added, and the mixture was held at 80°C for 15 min. Instead of CBD extraction, soil samples in the control treatment were extracted with sodium chloride (NaCl) at an equivalent ionic strength. After rinsing the soil residues three times with 1 M NaCl, SOC content of the residues in each treatment was measured. Fe-bound SOC was then calculated as follows

| (8) |

where SOCNaCl and SOCCBD refer to the SOC content (g kg−1) of the control treatment and reduction treatment, respectively.

To determine SOM protection by aggregates, we isolated three SOM fractions to measure C distributions in each fraction. Specifically, using the wet-sieving technique (56), 30 g of air-dried soil (<2 mm) was submerged in water for 5 min and then wet-sieved over 250 and 53 μm of sieves, consecutively. The fraction collected on the 250-μm sieve was macroaggregates (250 to 2000 μm), and that collected on the 53-μm sieve was microaggregates (53 to 250 μm). The fraction in the remaining suspension was silt + clay (<53 μm). Each fraction was then dried at 60°C. After isolating sand in macroaggregates and microaggregates with sodium hexametaphosphate, SOC concentrations of the three fractions were measured. Of the three fractions, the proportions of SOC distributed in macroaggregates and microaggregates were used to quantify SOM protection by aggregates (27).

We adopted the PLFA approach to assess soil microbial abundance and community composition. PLFAs were extracted according to the protocol described by Bossio and Scow (57). With 19:0 (methyl nonadecanoate, C20H40O2) as the internal standard, samples were then analyzed with a gas chromatograph (Agilent 6850, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The identification of the extracted fatty acid was based on a MIDI peak identification system (Microbial ID Inc., Newark, DE, USA). PLFAs specific to fungi (18:2ω6, 9c) and bacteria (i14:0, i15:0, a15:0, i16:0, a17:0, i17:0, 16:1ω7c, cy-17:0, 18:1ω7, cy19:0) were quantified (17). The composition of the microbial community was represented by the relative abundance of fungal PLFAs and F/B ratio.

Statistical analyses

We conducted mixed effects models (R package: nlme) to examine the difference in Q10 values between the topsoil and the subsoil. In the model, site and soil depth were set as fixed factors, and depth nested in replicate was treated as a random factor. Having detected no interaction effect between site and soil depth (table S1), we used paired t tests to compare the means of physicochemical properties between the topsoil and the subsoil. Linear regression models were then performed to identify the relationships of Q10 with aggregate protection and microbial communities. Before the analyses, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to assess the collinearity of the variables (acceptable collinearity VIF ≤ 2) (58). On the basis of this criterion, the collinearity between SOC distribution in macroaggregates and microaggregates could be partly omitted (VIF = 1.6), whereas the relative abundance of fungal PLFAs was closely correlated with F/B (VIF = 4.4), and thus, only the former was included in the model.

To further analyze the relative importance of different variables, we conducted variation partitioning analysis (R package: vegan) to partition the effects of aggregate protection and microbial communities on Q10 in various C pools. △Q10 (Q10 topsoil − Q10 subsoil, the difference in Q10 between the topsoil and the subsoil) for the two manipulative experiments was then calculated to test the role of aggregate protection and microbial communities. A positive value of △Q10 represents larger Q10 in the topsoil, while a negative value represents larger Q10 in the subsoil. The means of △Q10 between control and crush/inoculation treatments were compared using paired t tests. The decrease in △Q10 compared with the control indicates that crush/inoculation treatment reduces the difference in Q10 between the topsoil and the subsoil and vice versa. All of the statistical analyses were conducted with R version 3.2.1 (59), with a significance level of 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the IBCAS Sampling Campaign Teams for their assistance in field investigation, and we appreciate two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on an early version of this manuscript. Funding: This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA19070303); National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0503903); National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770557 and 31825006); Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDB-SSW-SMC049); and Chinese Academy of Sciences–Peking University Pioneer Cooperation Team. Author contributions: Y.Y. and L.C. conceived the idea. L.C., S.Q., and Y.Y. designed the research. S.Q., K.F., Q.Z., J.W., F.L., and J.Y. performed the experiments. S.Q. and L.C. analyzed the data. S.Q., Y.Y., and L.C. wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no financial or other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the corresponding author (yhyang@ibcas.ac.cn).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaau1218/DC1

Fig. S1. Field soil sampling and laboratory incubation.

Fig. S2. Effects of microorganism reciprocal transplant on Q10 for the two soil depths.

Fig. S3. Changes in the cumulative respired soil C with incubation time.

Fig. S4. Comparison between modeled and measured soil C flux.

Table S1. Analysis of variance table for Q10 values from different sites and soil depths.

Table S2. Comparison of topsoil and subsoil microbial communities at three sites.

Table S3. Physicochemical characteristics in the two soil depths at three sites.

Table S4. Prior parameter ranges for C pool partitioning coefficients (fi), decay rates (ki), and temperature sensitivity ().

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Jobbágy E. G., Jackson R. B., The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 10, 423–436 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontaine S., Barot S., Barré P., Bdioui N., Mary B., Rumpel C., Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply. Nature 450, 277–280 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson E. A., Janssens I. A., Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowther T. W., Todd-Brown K. E. O., Rowe C. W., Wieder W. R., Carey J. C., Machmuller M. B., Snoek B. L., Fang S., Zhou G., Allison S. D., Blair J. M., Bridgham S. D., Burton A. J., Carrillo Y., Reich P. B., Clark J. S., Classen A. T., Dijkstra F. A., Elberling B., Emmett B. A., Estiarte M., Frey S. D., Guo J., Harte J., Jiang L., Johnson B. R., Kröel-Dulay G., Larsen K. S., Laudon H., Lavallee J. M., Luo Y., Lupascu M., Ma L. N., Marhan S., Michelsen A., Mohan J., Niu S., Pendall E., Peñuelas J., Pfeifer-Meister L., Poll C., Reinsch S., Reynolds L. L., Schmidt I. K., Sistla S., Sokol N. W., Templer P. H., Treseder K. K., Welker J. M., Bradford M. A., Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104–108 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicks Pries C. E., Castanha C., Porras R. C., Torn M. S., The whole-soil carbon flux in response to warming. Science 355, 1420–1423 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M. A., Wieder W. R., Bonan G. B., Fierer N., Raymond P. A., Crowther T. W., Managing uncertainty in soil carbon feedbacks to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 751–758 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou T., Shi P., Hui D., Luo Y., Global pattern of temperature sensitivity of soil heterotrophic respiration (Q10) and its implications for carbon-climate feedback. J. Geophys. Res. 114, G02016 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosatta E., Ågren G. I., Soil organic matter quality interpreted thermodynamically. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31, 1889–1891 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rumpel C., Kögel-Knabner I., Deep soil organic matter—A key but poorly understood component of terrestrial C cycle. Plant Soil 338, 143–158 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conant R. T., Ryan M. G., Ågren G. I., Birge H. E., Davidson E. A., Eliasson P. E., Evans S. E., Frey S. D., Giardina C. P., Hopkins F. M., Hyvönen R., Kirschbaum M. U. F., Lavallee J. M., Leifeld J., Parton W. J., Megan Steinweg J., Wallenstein M. D., Martin Wetterstedt J. Å., Bradford M. A., Temperature and soil organic matter decomposition rates - synthesis of current knowledge and a way forward. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 3392–3404 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dungait J. A. J., Hopkins D. W., Gregory A. S., Whitmore A. P., Soil organic matter turnover is governed by accessibility not recalcitrance. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 1781–1796 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann J., Kleber M., The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 528, 60–68 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt M. W. I., Torn M. S., Abiven S., Dittmar T., Guggenberger G., Janssens I. A., Kleber M., Kögel-Knabner I., Lehmann J., Manning D. A. C., Nannipieri P., Rasse D. P., Weiner S., Trumbore S. E., Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 478, 49–56 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karhu K., Auffret M. D., Dungait J. A. J., Hopkins D. W., Prosser J. I., Singh B. K., Subke J.-A., Wookey P. A., Ågren G. I., Sebastià M.-T., Gouriveau F., Bergkvist G., Meir P., Nottingham A. T., Salinas N., Hartley I. P., Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration rates enhanced by microbial community response. Nature 513, 81–84 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldrop M. P., Wickland K. P., White R. III, Berhe A. A., Harden J. W., Romanovsky V. E., Molecular investigations into a globally important carbon pool: Permafrost-protected carbon in Alaskan soils. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 2543–2554 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillabel J., Cebrian-Lopez B., Six J., Merckx R., Experimental evidence for the attenuating effect of SOM protection on temperature sensitivity of SOM decomposition. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 2789–2798 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L., Liang J., Qin S., Liu L., Fang K., Xu Y., Ding J., Li F., Luo Y., Yang Y., Determinants of carbon release from the active layer and permafrost deposits on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 7, 13046 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balesdent J., Basile-Doelsch I., Chadoeuf J., Cornu S., Derrien D., Fekiacova Z., Hatté C., Atmosphere-soil carbon transfer as a function of soil depth. Nature 559, 599–602 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian J., Pausch J., Yu G., Blagodatskaya E., Gao Y., Kuzyakov Y., Aggregate size and their disruption affect 14C-labeled glucose mineralization and priming effect. Appl. Soil Ecol. 90, 1–10 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treat C. C., Wollheim W. M., Varner R. K., Grandy A. S., Talbot J., Frolking S., Temperature and peat type control CO2 and CH4 production in Alaskan permafrost peats. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 2674–2686 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knorr W., Prentice I. C., House J. I., Holland E. A., Long-term sensitivity of soil carbon turnover to warming. Nature 433, 298–301 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conant R. T., Drijber R. A., Haddix M. L., Parton W. J., Paul E. A., Plante A. F., Six J., Steinweg J. M., Sensitivity of organic matter decomposition to warming varies with its quality. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 868–877 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parton W. J., Schimel D. S., Cole C. V., Ojima D. S., Analysis of factors controlling soil organic matter levels in Great Plains Grasslands. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 51, 1173–1179 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkinson D. S., Coleman K., The turnover of organic carbon in subsoils. Part 2. Modelling carbon turnover. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 59, 400–413 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou X., Xu X., Zhou G., Luo Y., Temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon decomposition increased with mean carbon residence time: Field incubation and data assimilation. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 810–822 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang J., Li D., Shi Z., Tiedje J. M., Zhou J., Schuur E. A. G., Konstantinidis K. T., Luo Y., Methods for estimating temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter based on incubation data: A comparative evaluation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 80, 127–135 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Six J., Conant R. T., Paul E. A., Paustian K., Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant Soil 241, 155–176 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blagodatskaya E., Zheng X., Blagodatsky S., Wiegl R., Dannenmann M., Butterbach-Bahl K., Oxygen and substrate availability interactively control the temperature sensitivity of CO2 and N2O emission from soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 50, 775–783 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paterson E., Osler G., Dawson L. A., Gebbing T., Sim A., Ord B., Labile and recalcitrant plant fractions are utilised by distinct microbial communities in soil: Independent of the presence of roots and mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40, 1103–1113 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briones M. J., McNamara N. P., Poskitt J., Crow S. E., Ostle N. J., Interactive biotic and abiotic regulators of soil carbon cycling: Evidence from controlled climate experiments on peatland and boreal soils. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 2971–2982 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hicks Pries C. E., Sulman B. N., West C., O’Neill C., Poppleton E., Porras R. C., Castanha C., Zhu B., Wiedemeier D. B., Torn M. S., Root litter decomposition slows with soil depth. Soil Biol. Biochem. 125, 103–114 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahzad T., Rashid M. I., Maire V., Barot S., Perveen N., Alvarez G., Mougin C., Fontaine S., Root penetration in deep soil layers stimulates mineralization of millennia-old organic carbon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 124, 150–160 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pang X., Zhu B., Lü X., Cheng W., Labile substrate availability controls temperature sensitivity of organic carbon decomposition at different soil depths. Biogeochemistry 126, 85–98 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez G., Shahzad T., Andanson L., Bahn M., Wallenstein M. D., Fontaine S., Catalytic power of enzymes decreases with temperature: New insights for understanding soil C cycling and microbial ecology under warming. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 4238–4250 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barré P., Plante A. F., Cécillon L., Lutfalla S., Baudin F., Bernard S., Christensen B. T., Eglin T., Fernandez J. M., Houot S., Kätterer T., Le Guillou C., Macdonald A., van Oort F., Chenu C., The energetic and chemical signatures of persistent soil organic matter. Biogeochemistry 130, 1–12 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehmann J., Solomon D., Kinyangi J., Dathe L., Wirick S., Jacobsen C., Spatial complexity of soil organic matter forms at nanometre scales. Nat. Geosci. 1, 238–242 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNamara N. P., Black H. I. J., Beresford N. A., Parekh N. R., Effects of acute gamma irradiation on chemical, physical and biological properties of soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 24, 117–132 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kéraval B., Fontaine S., Lallement A., Revaillot S., Billard H., Alvarez G., Maestre F., Amblard C., Lehours A.-C., Cellular and non-cellular mineralization of organic carbon in soils with contrasted physicochemical properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 125, 286–289 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maire V., Alvarez G., Colombet J., Comby A., Despinasse R., Dubreucq E., Joly M., Lehours A.-C., Perrier V., Shahzad T., Fontaine S., An unknown oxidative metabolism substantially contributes to soil CO2 emissions. Biogeosciences 10, 1155–1167 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wieder W. R., Bonan G. B., Allison S. D., Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 909–912 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perveen N., Barot S., Alvarez G., Klumpp K., Martin R., Rapaport A., Herfurth D., Louault F., Fontaine S., Priming effect and microbial diversity in ecosystem functioning and response to global change: A modeling approach using the SYMPHONY model. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 1174–1190 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schimel J. P., Weintraub M. N., The implications of exoenzyme activity on microbial carbon and nitrogen limitation in soil: A theoretical model. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 549–563 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wieder W. R., Allison S. D., Davidson E. A., Georgiou K., Hararuk O., He Y., Hopkins F., Luo Y., Smith M. J., Sulman B., Todd-Brown K., Wang Y.-P., Xia J., Xu X., Explicitly representing soil microbial processes in Earth system models. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 1782–1800 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding J., Li F., Yang G., Chen L., Zhang B., Liu L., Fang K., Qin S., Chen Y., Peng Y., Ji C., He H., Smith P., Yang Y., The permafrost carbon inventory on the Tibetan Plateau: A new evaluation using deep sediment cores. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 2688–2701 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H., Zhu Q., Peng C., Wu N., Wang Y., Fang X., Gao Y., Zhu D., Yang G., Tian J., Kang X., Piao S., Ouyang H., Xiang W., Luo Z., Jiang H., Song X., Zhang Y., Yu G., Zhao X., Gong P., Yao T., Wu J., The impacts of climate change and human activities on biogeochemical cycles on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 2940–2955 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding J., Chen L., Zhang B., Liu L., Yang G., Fang K., Chen Y., Li F., Kou D., Ji C., Luo Y., Yang Y., Linking temperature sensitivity of soil CO2 release to substrate, environmental, and microbial properties across alpine ecosystems. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1310–1323 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Reference Base for Soil Resources, “International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps” (World Soil Resources Reports No. 106, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2015).

- 48.Neff J. C., Hooper D. U., Vegetation and climate controls on potential CO2, DOC and DON production in northern latitude soils. Glob. Change Biol. 8, 872–884 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rey A., Jarvis P., Modelling the effect of temperature on carbon mineralization rates across a network of European forest sites (FORCAST). Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1894–1908 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schädel C., Schuur E. A. G., Bracho R., Elberling B., Knoblauch C., Lee H., Luo Y., Shaver G. R., Turetsky M. R., Circumpolar assessment of permafrost C quality and its vulnerability over time using long-term incubation data. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 641–652 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hastings W. K., Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 57, 97–109 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metropolis N., Rosenbluth A. W., Rosenbluth M. N., Teller A. H., Teller E., Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 1087–1092 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt M. W. I., Knicker H., Hatcher P. G., Kögel-Knabner I., Improvement of 13C and 15N CPMAS NMR spectra of bulk soils, particle size fractions and organic material by treatment with 10% hydrofluoric acid. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 48, 319–328 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simpson M. J., Simpson A. J., The chemical ecology of soil organic matter molecular constituents. J. Chem. Ecol. 38, 768–784 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lalonde K., Mucci A., Ouellet A., Gélinas Y., Preservation of organic matter in sediments promoted by iron. Nature 483, 198–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Six J., Elliott E. T., Paustian K., Doran J. W., Aggregation and soil organic matter accumulation in cultivated and native grassland soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 62, 1367–1377 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bossio D. A., Scow K. M., Impacts of carbon and flooding on soil microbial communities: Phospholipid fatty acid profiles and substrate utilization patterns. Microb. Ecol. 35, 265–278 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Craney T. A., Surles J. G., Model-dependent variance inflation factor cutoff values. Qual. Eng. 14, 391–403 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 59.R Development Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaau1218/DC1

Fig. S1. Field soil sampling and laboratory incubation.

Fig. S2. Effects of microorganism reciprocal transplant on Q10 for the two soil depths.

Fig. S3. Changes in the cumulative respired soil C with incubation time.

Fig. S4. Comparison between modeled and measured soil C flux.

Table S1. Analysis of variance table for Q10 values from different sites and soil depths.

Table S2. Comparison of topsoil and subsoil microbial communities at three sites.

Table S3. Physicochemical characteristics in the two soil depths at three sites.

Table S4. Prior parameter ranges for C pool partitioning coefficients (fi), decay rates (ki), and temperature sensitivity ().