Abstract

Objective:

White matter (WM) microstructure changes are increasingly recognized as a mechanism of age-related cognitive differences. This study examined the associations between patterns of WM microstructure and cognitive performance on the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Brain Health Assessment (BHA) subtests of memory (Favorites), executive functions and speed (Match), and visuospatial skills (Line Orientation) within a sample of older adults.

Method:

Fractional anisotropy (FA) in WM tracts and BHA performance were examined in 84 older adults diagnosed as neurologically healthy (47), with mild cognitive impairment (19), or with dementia (18). The relationships between FA and subtest performances were evaluated using regression analyses. We then explored whether regional WM predicted performance after accounting for variance explained by global FA.

Results:

Memory performance was associated with FA of the fornix and the superior cerebellar peduncle, and executive functions and speed with the body of the corpus callosum. The fornix – memory association, and the corpus callosum – executive association, remained significant after accounting for global FA. Neither tract-based nor global FA was associated with visuospatial performance.

Conclusions:

Memory and executive functions are associated with different patterns of WM diffusivity. Findings add insight into WM alterations underlying age-and-disease-related cognitive decline.

Keywords: white matter microstructure, diffusion tensor imaging, cognition, brief assessment, mild cognitive impairment, dementia

Introduction

Cerebral white matter is important for cognition, and microstructural changes contribute to age-related cognitive deficits (Bennet & Madden, 2014). Reductions in white matter microstructure are related to poorer performance across several cognitive domains among clinically normal older adults (Vernooij et al., 2009). Recent literature also demonstrates that white matter abnormalities are an early feature of incipient neurodegenerative syndromes including Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Fischer, Wolf, Scheurich, & Fellgiebel, 2015). Microstructural alterations of white matter are affected in AD relative to controls in several regions (Sexton et al., 2011), and are associated with rate of cognitive decline (Brickman et al., 2008). It remains unclear, however, whether impairments arise from tract-based in addition to global changes in white matter (Bennett & Madden, 2014). Clarifying the relationships between white matter integrity and cognition may offer new insights into diagnosis and treatment planning. The objective of this study was to determine the importance of regional white matter tracts and global white matter for performance in cognitive domains that are commonly affected in neurocognitive disorders and assessed during dementia evaluations.

We used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to investigate the relationships between tract-based and global white matter microstructure and performance on measures of memory, executive function and speed, and visuospatial skills. We used subtests from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Brain Health Assessment (BHA), a tablet-based cognitive assessment for the detection and classification of mild neurocognitive disorders. In a prior study that examined regional gray matter correlates of these subtests (Possin et al., 2018), memory performance correlated with medial temporal volumes, executive function and speed performance was associated with frontal, parietal and basal ganglia volumes, and visuospatial performance correlated with right parietal volumes. We hypothesized that in a whole-brain DTI tract analyses, memory performance would show association with white matter pathways in the temporal lobes, executive function and speed performance with subcortical and corpus callosum tracts, and visuospatial performance with white matter microstructure within the right parietal lobe.

Method

Participants

A total of 84 participants [47 neurologically healthy older adults; 19 Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI; Albert et al., 2011); 18 dementia (Major Neurocognitive Disorder, American Psychiatric Association, 2013)] were recruited from longitudinal studies at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center. We included participants who received magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with DTI within 180 days of BHA administration. Participants were diagnosed in multidisciplinary clinical consensus conferences (Appendix 1). Participants were diverse in terms of dementia diagnosis, cognitive performance, and patterns of white matter microstructure. Demographic and clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and BHA scores by diagnostic group

| Diagnosis | N | Age | Education | Males | MMSE | Favorites | Match | Line Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 47 | 74.6(5.5) | 17.8(1.8) | 22 | 29. 4(0.9) | 15.3(4.2) | 48.2(6.7) | 4.7(2.3) |

| MCI | 19 | 71.2(11.6) | 18.6(2.4) | 10 | 28.3(1.2) | 7.7(5.3) | 40.9(11.1) | 5.8(2.1) |

| Dementia | 18 | 65.2(11.0) | 16.8(1.9) | 6 | 21.7(3.7) | 6.1(4.8) | 31.7(12.4) | 6.9(4.2) |

| AD | 5 | 66.5(11.0) | 18.3(2.6) | 1 | 22.3(4.9) | 3.8(6.9) | 24.0(17.6) | 9. 2(4.1) |

| bvFTD | 4 | 58.0(17.6) | 17.5(1.0) | 3 | 25.0(2.8) | 5.3(1.5) | 41.3(3.5) | 8.2(4.8) |

| PPA | 7 | 66.0(5.9) | 15.3(0.8) | 0 | 20.0(2.1) | 8.0(4.6) | 31.2(10.3) | 5.8(4.2) |

| PSP-S | 2 | 74.5(5.0) | 17.0(1.4) | 2 | 7.0(5.0) | 24.0(11.3) | 3.5(0.5) |

Note. Values represent mean (SD).

MMSE= Mini Mental State Examination (Folstein et al., 1975); NC= normal control; MCI= mild cognitive impairment; AD=Alzheimer’s disease; bvFTD= behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; PPA= primary progressive aphasia including the nonfluent (N=4), logopenic (N=2), and semantic (N=1) variants; PSP-S= progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome

The Brain Health Assessment

The BHA was programmed in the TabCAT framework developed at UCSF (https://memory.ucsf.edu/tabcat) and was administered to participants by research assistants who were trained and supervised by a licensed neuropsychologist. During the BHA, participants were seated in a chair at a desk with a 9.7 inch iPad positioned horizontally in front of them with the back of the tablet propped 1 inch up from the desk surface. The assistant sat next to the participant for all tasks.

The Favorites memory test requires the participant to learn to associate faces with food and animal words across two learning trials. After each learning trial, the faces reappear one at a time, and the participant is asked to recall the food and animal associated with each face. The examiner records participant responses on a sheet of paper and later enters them into the tablet for scoring. Accuracy is summed across two immediate recall and one 10-minute delay recall trial. The Match executive function and speed test requires the participant to quickly match numbers with simple abstract pictures using a legend that remains visible throughout the task. When a number appears in the middle of the screen, participants are asked to tap the corresponding picture as quickly as possible. Accurate responses in two minutes are totaled. The Line Orientation visuospatial test requires participants to identify which of two lines is parallel to a target line. The “angle difference” between the non-match line and the correct match line is staircased based on response accuracy. Higher scores on Favorites and Match, and lower scores on Line Orientation, represent better performance.

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Image Processing

Diffusion tensor imaging.

Participants underwent MRI at the UCSF Memory and Aging Neuroscience Imaging Center using a Siemens 12-channel head coil on a 3 Tesla Siemens Prisma scanner (Appendix 1). Diffusion Weighted Images (DTI) were acquired using single-short spin-echo sequence. White matter tracts were masked using the ICBM-DTI-81 white matter labels and tract atlas (Mori, Wakana, van Zijl, & Nagar-Poetscher, 2005). White matter microstructure was determined using a DTI-derived metric, and mean FA was computed from 27 white matter tracts throughout the brain. Global FA was calculated as mean FA across all voxels in the white matter atlas. Details on DTI acquisition and processing are provided in Appendix 1.

Statistical Analyses

All 84 participants who underwent DTI imaging and completed Favorites, Match, and Line Orientation were included in the analyses. We used histograms to identify possible outliers. Across the data for all 3 tests and 27 major tracts, 25 data points were detached from the distribution and were greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean, and were winsorized to three standard deviations from the mean to reduce their influence. Scatter plots depicting primary findings by diagnostic group are shown in Supplementary Figures 1–3. To determine which of the 27 major tracts in frontal, temporal, parietal and subcortical regions uniquely contributed to performance on each subtest, we performed stepwise regressions with backwards elimination. White matter tract FA values were averaged and investigated bilaterally for Favorites and Match analyses, but were investigated separately by hemisphere for Line Orientation because we hypothesized stronger right hemisphere associations for this task. To avoid multicollinearity while allowing for broad consideration of potential regions, we first reduced the number of potential predictors for each regression model by correlating all 27 major white matter tracts throughout the brain separately with test performance. We selected white matter tracts for inclusion for which rp values were at least 0.30 (a medium effect size; Cohen, 1992). In each regression, we sequentially eliminated the weakest predictors until only predictors with a p-value of <.05 remained. We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine if our results were similar after controlling for dementia severity (Clinical Dementia Rating; Morris, 1993), and after sequentially removing each of the four dementia subtypes. We also report the significance of the individual correlations with all 27 tracts with Type I error correction using the Hochberg method (Hochberg, 1988; Supplementary Tables 1–2). The adjusted p-values used to determine statistical significance after correcting for multiple comparisons were: p < 0.0023 for Favorites, p < 0.0033 for Match, and p < 0.0011 for Line Orientation performance. For all correlation and regression analyses, age and sex were included as covariates.

In secondary analyses, we explored the importance of regional white matter microstructure in predicting domain-specific cognition after accounting for global white matter. Separately for each cognitive test, we accounted for the effects of global FA, age, and sex, and saved the residuals. Next, we used the regional FA values that were significant in primary regression analyses to predict these residuals.

Results

Memory

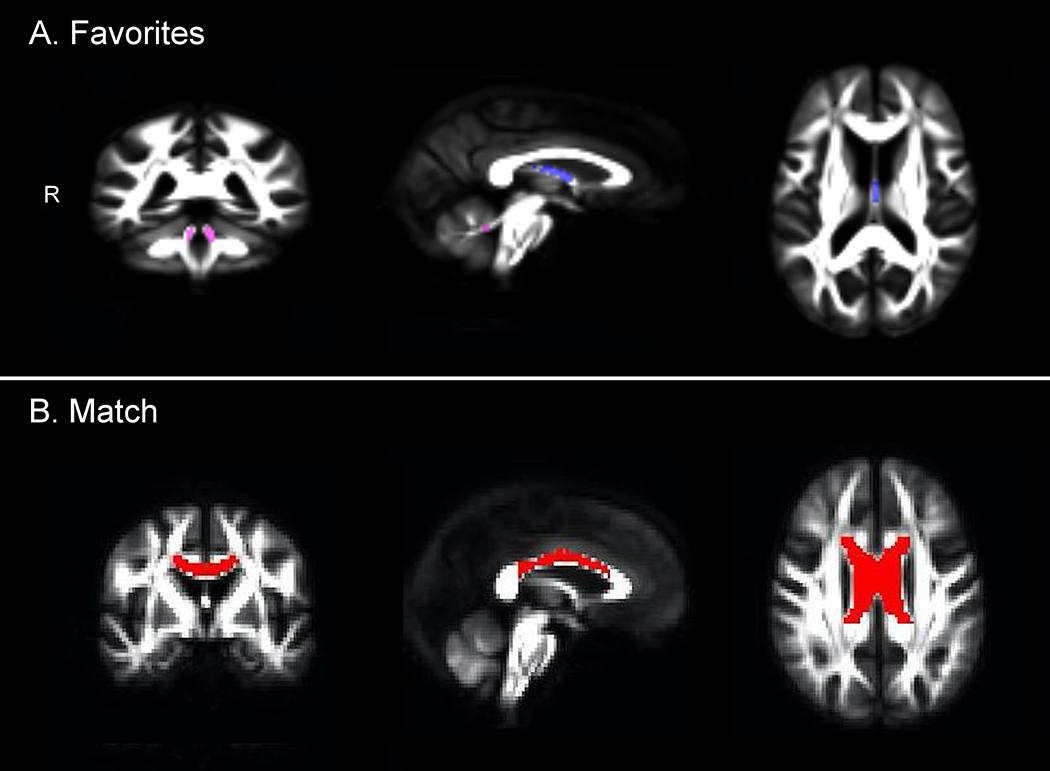

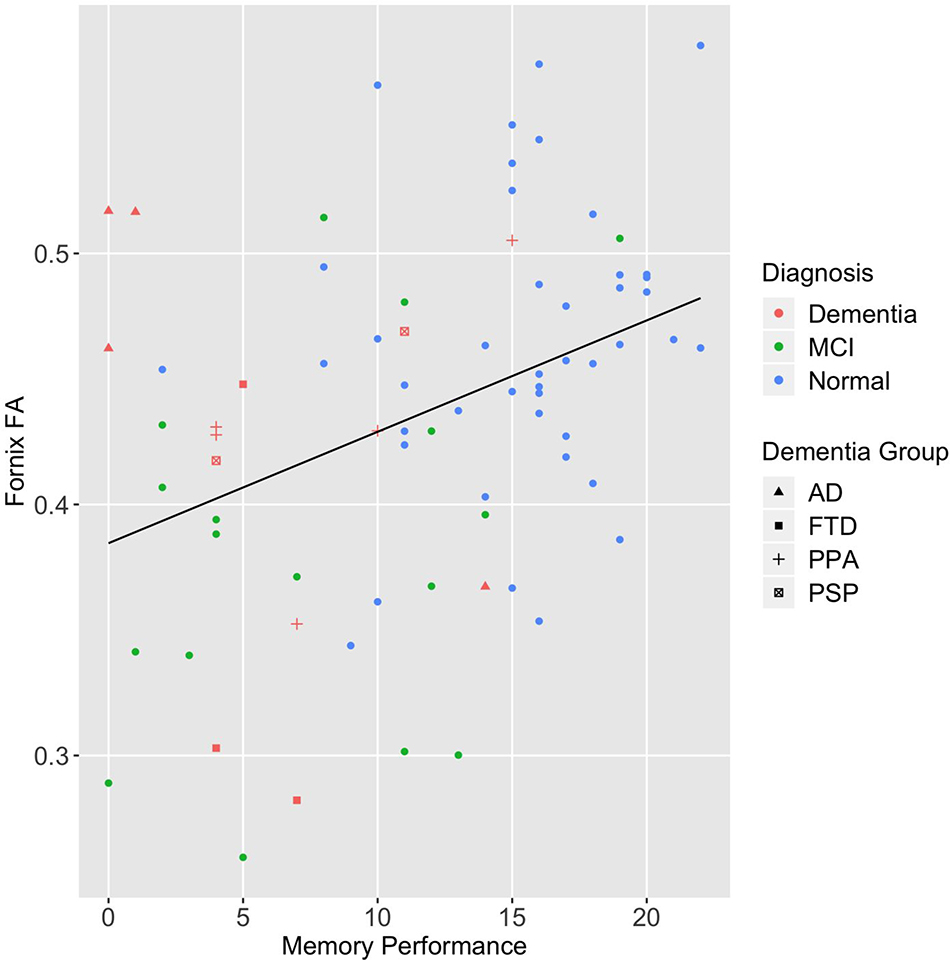

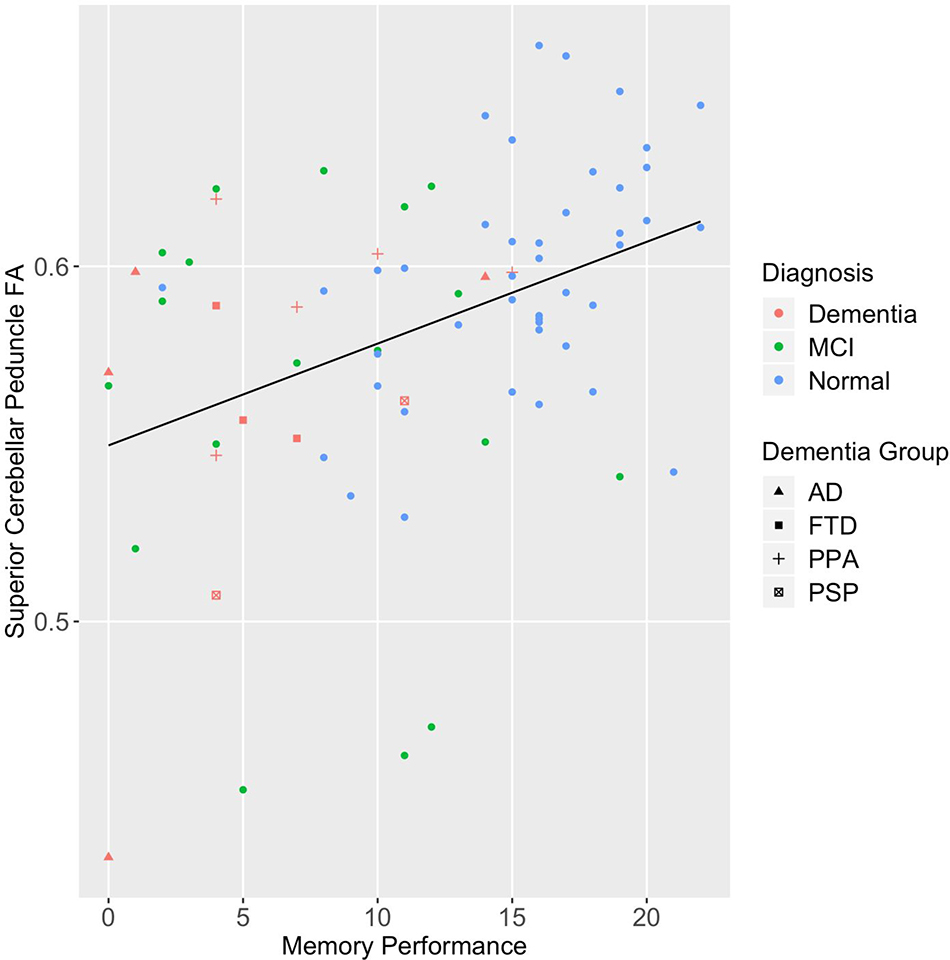

Partial correlation coefficients of Favorites memory performance and white matter microstructure are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Based on a moderate correlation with Favorites performance (rp’s ≥ 0.3), FA in thirteen white matter tracts in temporal, frontal, corpus callosal, and also subcortical regions were included in the regression. In the final stepwise regression model, FA of the column and body of the fornix (B=30.78; p=.001) and the superior cerebellar peduncle (B=41.76; p=.007) were retained (Supplementary Table 3; Figure 1). In sensitivity analyses, FA of the column and body of the fornix (B= 22.96, p=.03) and the superior cerebellar peduncle (B=34.07, p=.04) remained significant after controlling for dementia severity. After sequentially removing each of the four dementia subtypes, the column and body of the fornix remained significant in all analyses (all p’s<.05), and the superior cerebellar peduncle was significant when each group was removed except AD (p=.08). The individual correlations with multiple comparison correction produced similar results: the same regions significantly correlated with Favorites performance, and the fornix stria terminalis and the superior longitudinal fasciculus additionally reached significance (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

WM tracts that uniquely predict performance on the Favorites memory and the Match executive function and speed test performance in regression analyses. The fornix is shown in blue (A), the superior cerebellar peduncle in pink (A), and the body of the corpus callosum in red (B).

In secondary analyses, global FA was significantly associated with Favorites memory performance after controlling for age and sex (B=87.02, p=.001). FA of the fornix (B=18.90, p=.04) but not the superior cerebellar peduncle (B=28.21, p=.06) significantly predicted the residuals.

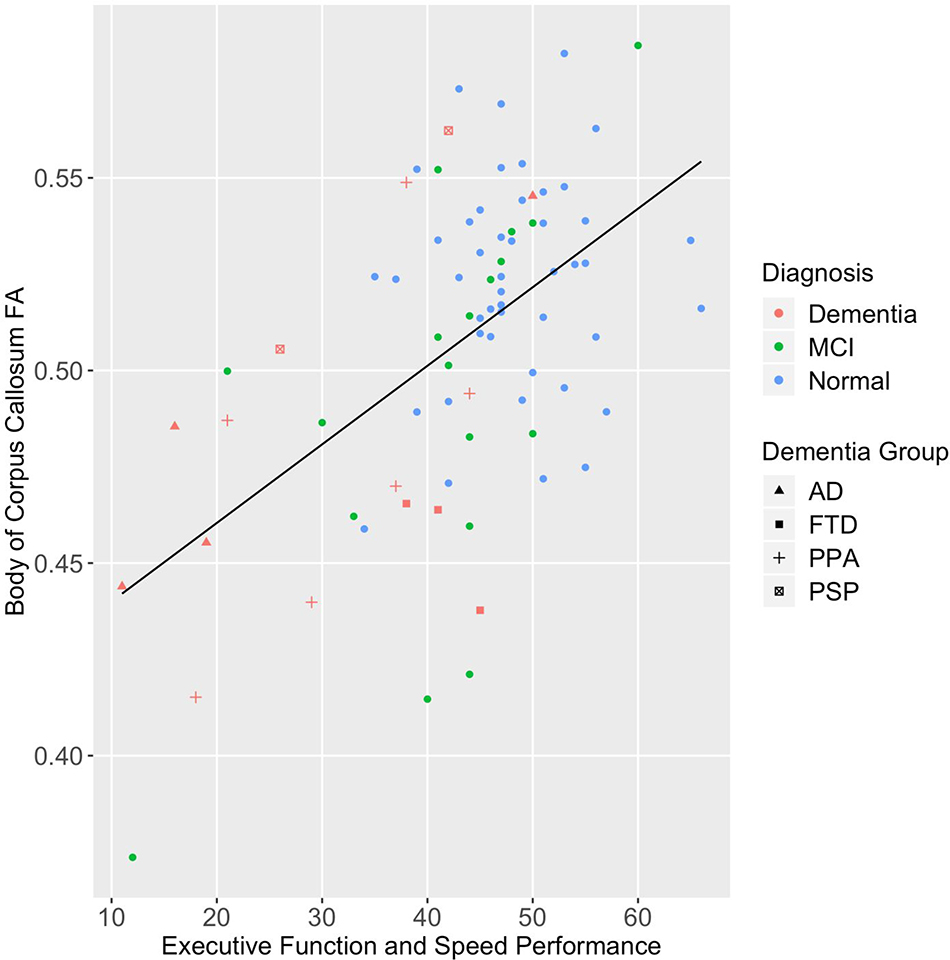

Executive Function and Speed

FA in thirteen white matter pathways in frontal, callosal, temporal, and subcortical regions were included in the regression. In the final stepwise regression model, FA of the body of the corpus callosum (B=147.18; p<.001) was retained (Supplementary Table 4: Figure 1). In sensitivity analyses, after sequentially removing each of the four dementia subtypes, the body of the corpus callosum remained significant in all analyses (all p’s<.05). After controlling for dementia severity, the body of the corpus callosum was not significant (B=58.54, p=0.08). In addition to this region, individual correlations with multiple comparison correction were significant for the genu and the splenium of the corpus callosum, the external capsule, the superior cerebellar peduncle, the superior longitudinal fasciculus, the sagittal stratum, the cingulate gyrus, the uncinate fasciculus, the fornix stria terminalis, and the fornix column and body (Supplementary Table 1).

In secondary analyses, global FA was significantly associated with Match executive and speed performance (B=173.35, p<.001), and FA of the body of the corpus callosum significantly predicted the residuals (B=52.93, p=.048).

Visuospatial Skills

Partial correlation coefficients of Line Orientation performance and FA of white matter microstructure are reported in Supplementary Table 2. None of the 27 right-hemisphere or 27 left-hemisphere white matter tracts met the threshold for inclusion in the regression model (all rps< 0.30), or exhibited significant individual correlations with Line Orientation after correcting for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Table 2). In secondary analyses, global FA was not associated with visuospatial performance (B=−15.60, p=.23).

Discussion

We investigated the relationships of memory, executive function and speed, and visuospatial performance on the UCSF Brain Health Assessment with regional and global white matter microstructure. In regression analyses, memory performance was uniquely predicted by integrity in a white matter temporal lobe tract important for memory, and by a tract in the cerebellum. Executive functions and speed was predicted by microstructure of a corpus callosum tract important for efficient cognitive functions. Visuospatial skills did not exhibit significant associations with white matter microstructural integrity in regional or whole brain analyses. Findings support the differential recruitment of regional white matter tracts for domain-specific cognitive skills.

The Favorites test of memory requires participants to learn and recall face – word associations. Performance was associated with white matter integrity in the fornix and the superior cerebellar peduncle. Results were similar after controlling for dementia severity, indicating that associations were not specific to a particular functional level. Global FA significantly predicted memory performance, and integrity of the fornix but not the superior cerebellar peduncle significantly predicted residual variance, indicating an important role for the fornix in memory beyond global white matter. The fornix is a critical component of the limbic system that constitutes the major white matter pathways from the hippocampi. Fornicial microstructural integrity is shown to play an important role in episodic memory performance, and white matter deterioration of the fornix is a sensitive predictor of conversion from normal cognition to MCI, as well as from MCI to AD (Nowrangi & Rosenberg, 2015). Favorites memory performance also correlated with the stria terminalis, a band of fibers receiving projections from the hippocampus via the fornix. The correlation with the superior longitudinal fasciculus, an association fiber connecting lateral prefrontal to parietal regions, is consistent with the view that both frontal and parietal systems are important for memory (Fletcher & Henson, 2001). Results suggest that episodic memory is a complex cognitive process relying on a widely distributed network of white matter connections, especially limbic tracts, but also cerebellar and fronto-parietal connections.

The Match test of executive functions and processing speed requires participants to quickly match numbers with a picture using a visible legend. Better performance was uniquely associated with white matter integrity of the body of the corpus callosum. Global FA significantly predicted executive functions and speed, and the corpus callosum significantly predicted residual variance. Prior research has established an important role for the corpus callosum in executive function and speed (e.g., Bettcher et al., 2016), consistent with its anatomical function connecting and enabling communication between hemispheres. FA in several additional regions correlated with Match, specifically the full extent of the corpus callosum, the superior longitudinal fasciculus, cingulate gyrus, external capsule, uncinate fasciculus, sagittal stratum, superior cerebellar peduncle, and the fornix stria terminalis. The broad array of correlations with Match is consistent with the view that white matter integrity is particularly crucial for efficient executive functions and speeded cognition in aging (Jacobs et al., 2013).

The Line Orientation test requires subjects to identify which of two lines is parallel to a target line. We did not find significant associations between visuospatial performance and regional or whole brain white matter microstructure. No correlations with tract-based FA, including parietal tracts, were significant after multiple comparison correction or met our effect size threshold to be included in regression analyses. While many studies have demonstrated that right parietal gray matter is important for visuospatial functions, the gray matter correlates are circumscribed compared to those for memory and executive functions (Tranel et al., 2009; Possin et al., 2018), and efficient white matter communication may therefore be less critical. Mild changes in white matter microstructure may have less of an impact on visuospatial processing than on executive function or memory.

The study sample was English speaking with high education, which limits generalizability to other clinical populations. Future work is planned with samples more diverse in terms of cultural background and education. In addition, our sample was not large enough to separately evaluate white matter – cognition relationships in diagnostic subgroups, in which there may be unique relationships. This type of analysis is needed to make clinical interpretations about how white matter changes in specific groups, such as Alzheimer’s disease, contribute to domain-specific cognitive deficits, and also the extent to which the reported findings generalize to the complete spectrum of dementias and MCI.

In summary, we found different patterns of correlations between the UCSF BHA subtests of memory, executive function and speed, and visuospatial skills with white matter tract integrity. Memory performance was associated with white matter microstructure of the fornix and superior cerebral peduncle, while executive function and speed performance with corpus callosum integrity. The memory–fornix, and the executive function–corpus callosum associations remained significant even after accounting for variance explained by global white matter, suggesting that microstructural changes in these tracts impact cognition beyond global white matter changes. In contrast, visuospatial performance was not associated with regional or whole brain white matter integrity. Given the growing prevalence of neurocognitive disorders among older individuals and advances in health care, future investigations of white matter microstructural health and cognition will be important to further elucidate mechanisms of cognitive decline.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our study participants and their families. This study was supported by the Global Brain Health Institute, Quest Diagnostics, the National Institute on Aging (K23 AG037566-01A1, ADRC P50 AG023501, P01 AG019724), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (UG3 NS105557-01), and the Larry L. Hillblom Network Aging Grant for the Prevention of Age-Associated Cognitive Decline (2014-A-004-NET).

Appendix 1. Supplementary Methods

Participants

Participants were diagnosed in multidisciplinary clinical consensus conferences based upon the results of a comprehensive neurological evaluation, a 60-minute standard neuropsychological assessment, and a functional interview with an informant. Participants were excluded if they presented with a major psychiatric illness, another neurological condition affecting cognition, a history of substance abuse, or a major medical illness. A Clinical Dementia Rating score > 0 and a Geriatric Depression Scale >15 were exclusionary for controls.

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Image Processing

Whole brain T1 images were acquired using Magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) in the axial plane: TR=2300ms; TE=3.43ms; TI=900 ms; flip angle=9; slice thickness=1 mm; FOV=256*224 mm; voxel size=1 mm*1mm; matrix size=256*224; and number of slices=176. Diffusion Weighted Images (DTI) were acquired using single-short spin-echo sequence with the following parameters: TR=5300 ms; TE=88 ms; TI=2500 ms; flip angle=90; FOV=256*256 mm; two diffusion values of b=0 and 1000 s/mm; 12 diffusion directions; four repeats; 40 slices; matrix size=128*128; voxel size=2 mm*2 mm; slice thickness=3 mm; and GRAPPA=2.

For DTI images, we used FSL software to co-register the diffusion direction images with the b = 0 image, then applied a gradient direction eddy current and distortion correction. Diffusion tensors were calculated using a non-linear least-squares algorithm from Diffusion Imaging in Python (Dipy; Garyfalidis et al., 2014). After quality control, participants’ tensors (four dimensional images) were registered linearly and non-linearly into a common space using DTI-TK (Zhang, Yshkevich, Alexander, & Gee, 2006). Tensors were moved into the group template. Once in the group space, diffusion tensor images were diagonalized to extract the diffusion metrics like FA using Dipy (Garyfalidis et al., 2014).

Supplementary Figure 1.

Scatter plot of Favorites memory performance and FA of the column and body of the fornix by diagnostic group.

Note. MCI= mild cognitive impairment; AD= Alzheimer’s disease; FTD= behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; PPA= primary progressive aphasia; PSP= progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome

Supplementary Figure 2.

Scatter plot of Favorites memory performance and FA of the superior cerebellar peduncle by diagnostic group.

Note. MCI= mild cognitive impairment; AD= Alzheimer’s disease; FTD= behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; PPA= primary progressive aphasia; PSP= progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome

Supplementary Figure 3.

Scatter plot of Match executive function and speed performance and FA of the superior cerebellar peduncle by diagnostic group.

Note. MCI= mild cognitive impairment; AD= Alzheimer’s disease; FTD= behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; PPA= primary progressive aphasia; PSP= progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome

Supplementary Table 1.

Correlations of Memory and Executive Function/Speed Performance with white matter tracts.

| Memory: Favorites | Executive/Speed: Match | |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal tracts | ||

| Superior longitudinal fasciculus | 0.40* | 0.42* |

| Cingulate gyrus | 0.30 | 0.40* |

| Anterior corona radiata | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| Posterior corona radiata | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Superior corona radiata | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| Callosal tracts | ||

| Genu of corpus callosum | 0.33 | 0.46* |

| Body of corpus callosum | 0.38* | 0.54* |

| Splenium of corpus callosum | 0.32 | 0.43* |

| Tapetum | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Temporal tracts | ||

| Column and body of fornix | 0.44* | 0.33* |

| Fornix stria terminalis | 0.46* | 0.34* |

| Cingulum hippocampus | 0.34 | 0.28 |

| Uncinate fasciculus | 0.34 | 0.36* |

| Posterior tracts | ||

| Sagittal stratum | 0.34 | 0.35* |

| Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus | 0.14 | 0.23 |

| Subcortical tracts | ||

| Anterior limb of internal capsule | 0.18 | 0.27* |

| Posterior limb of internal capsule | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| Retrolenticular part of internal capsule | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| External capsule | 0.32 | 0.40* |

| Posterior thalamic radiation | 0.20 | 0.32 |

| Pontine crossing tract | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| Cerebral peduncle | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| Superior cerebellar peduncle | 0.40* | 0.32 |

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| Middle cerebellar peduncle | 0.28 | 0.14 |

Note. All correlations control for age and sex.

Significant after multiple comparisons correction (p < 0.0024 for Favorites, p < 0.0033 for Match).

Supplementary Table 2.

Correlations of visuospatial performance with white matter tracts.

| Visuospatial: Line Orientation | |

|---|---|

| Frontal tracts | |

| Superior longitudinal fasciculus (L) | −0.11 |

| Superior longitudinal fasciculus (R) | −0.15 |

| Cingulate gyrus (L) | −0.19 |

| Cingulate gyrus (R) | −0.09 |

| Anterior corona radiata (L) | −0.20 |

| Anterior corona radiata (R) | −0.23 |

| Posterior corona radiata (L) | 0.02 |

| Posterior corona radiata (R) | 0.02 |

| Superior corona radiata (L) | −0.01 |

| Superior corona radiata (R) | 0.07 |

| Callosal tracts | |

| Genu of corpus callosum | −0.24 |

| Body of corpus callosum | −0.26 |

| Splenium of corpus callosum | −0.16 |

| Tapetum (L) | −0.04 |

| Tapetum (R) | 0.08 |

| Temporal tracts | |

| Column and body of fornix | −0.04 |

| Fornix stria terminalis (L) | −0.20 |

| Fornix stria terminalis (R) | −0.18 |

| Cingulum hippocampus (L) | −0.09 |

| Cingulum hippocampus (R) | −0.09 |

| Uncinate fasciculus (L) | −0.18 |

| Uncinate fasciculus (R) | −0.13 |

| Posterior tracts | |

| Sagittal stratum (L) | −0.19 |

| Sagittal stratum (R) | −0.17 |

| Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus (L) | −0.03 |

| Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus (R) | −0.11 |

| Subcortical tracts | |

| Anterior limb of internal capsule (L) | −0.16 |

| Anterior limb of internal capsule (R) | −0.15 |

| Posterior limb of internal capsule (L) | −0.03 |

| Posterior limb of internal capsule (R) | 0.01 |

| Retrolenticular part of internal capsule (L) | 0.03 |

| Retrolenticular part of internal capsule (R) | 0.15 |

| External capsule (L) | −0.23 |

| External capsule (R) | −0.19 |

| Posterior thalamic radiation (L) | −0.23 |

| Posterior thalamic radiation (R) | −0.14 |

| Pontine crossing tract | 0.06 |

| Cerebral peduncle (L) | −0.11 |

| Cerebral peduncle (R) | −0.03 |

| Superior cerebellar peduncle (L) | 0.03 |

| Superior cerebellar peduncle (R) | 0.01 |

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle (L) | −0.06 |

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle (R) | −0.06 |

| Middle cerebellar peduncle | 0.00 |

Note. All correlations control for age and sex.

Significant after multiple comparisons correction (p < 0.00114 for Line Orientation).

Supplementary Table 3.

Summary of backward elimination regression models for regions predicting memory performance.

| Model/Order of region removed | B | 95% CI for B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Body of corpus callosum | 0.51 | (−78.12, 79.14) | 0.99 |

| 2. Sagittal stratum | −12.30 | (−72.42, 47.82) | 0.68 |

| 3. Cingulum hippocampus | 15.07 | (−41.58, 71.71) | 0.60 |

| 4. External capsule | −19.74 | (−98.55, 59.06) | 0.62 |

| 5. Uncinate fasciculus | 15.86 | (−33.03, 64.75) | 0.52 |

| 6. Cingulate gyrus | −11.79 | (−61.21, 37.63) | 0.64 |

| 7. Cerebral peduncle | 12.68 | (−28.67, 54.02) | 0.54 |

| 8. Genu of corpus callosum | 14.99 | (−29.92, 59.90) | 0.51 |

| 9. Superior longitudinal fasciculus | 38.54 | (−15.13, 92.21) | 0.16 |

| 10. Splenium of corpus callosum | −34.16 | (−84.81, 16.50) | 0.18 |

| 11. Fornix stria terminalis | 40.67 | (−6.22, 87.56) | 0.09 |

| 12. Superior cerebellar peduncle | 41.76 | (12.02, 71.49) | 0.007* |

| Column and body of fornix | 30.78 | (12.44, 49.12) | 0.001* |

| Age | 0.20 | (0.07, 0.34) | 0.004* |

| Gender | 0.46 | (−1.97, 2.89) | 0.71 |

Note.

p<.05

Supplementary Table 4.

Summary of backward elimination for regions predicting executive and speed performance

| Model/Order of region removed | B | 95% CI for B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cingulate gyrus | −1.47 | (−106.48, 103.55) | 0.98 |

| 2. Sagittal stratum | −4.51 | (−109.76, 100.75) | 0.93 |

| 3. Fornix stria terminalis | 5.88 | (−94.09, 105.85) | 0.91 |

| 4. Uncinate fasciculus | −11.88 | (−98.52, 74.75) | 0.79 |

| 5. External capsule | 39.65 | (−104.97, 184.28) | 0.59 |

| 6. Splenium of corpus callosum | −31.33 | (−155.04, 92.39) | 0.62 |

| 7. Column and body of fornix | 9.31 | (−29.46, 48.08) | 0.63 |

| 8. Superior cerebellar peduncle | 17.33 | (−41.24, 75.89) | 0.56 |

| 9. Cingulum hippocampus | −37.61 | (−122.37, 47.15) | 0.38 |

| 10. Genu of corpus callosum | 56.57 | (−45.51, 158.65) | 0.27 |

| 11. Superior longitudinal fasciculus | 72.41 | (−29.41, 174.23) | 0.16 |

| 12. Anterior corona radiata | −81.93 | (−181.93, 18.07) | .11 |

| 13. Body of corpus callosum | 143.50 | (91.95, 195.04) | <0.001* |

| Age | −0.09 | (−0.32, 0.15) | 0.45 |

| Gender | 0.98 | −.36, 5.31) | 0.66 |

Note.

p<.05

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Katherine L. Possin has received grant support from Quest Diagnostics. Katherine P. Rankin has received grant support from Quest Diagnostics and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen PC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, & Phelps CH (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging- Alzhiemer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 7(3), 270–279. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ & Madden DJ (2014). Disconnected aging: Cerebral white matter integrity and age-related differences in cognition. Neuroscience, 276, 187–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettcher BM, Mungas D, Patel N, Elofson J, Dutt S, Wynn M, Watson CL, Stephens M, Walsh CM, & Kramer JH (2016). Neuroanatomical Substrates of Executive Functions: Beyond Prefrontal Structures. Neuropsychologia, 85, 100–109. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Honig LS, Scarmeas N, Tatarina O, Sanders L, Albert MA, Brandt J, Blacker D, & Stern Y (2008). Measuring cerebral atrophy and white matter hyperintensity burden to predict the rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology, 65(9), 1202–1208. 10.1001/archneur.65.9.1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer FU, Wolf D, Scheurich A, Fellgiebel A, & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2015). Altered whole-brain white matter networks in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage: Clinical, 8, 660–666. 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC & Henson RNA (2001). Frontal lobes and human memory: Insights from functional neuroimaging. Brain, 124(5), 849–881, doi: 10.1093/brain/124.5.849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garyfallidis E, Bret M, Amirbekian B, Rokem A, van der Walt S, Descoteaux M, & Nimmo-Smith I (2014). Dipy, a library for the analysis of diffusion MRI data. Frontiers in Neuroimformatics, 8(8). doi: 10.3389/fnif.2014.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y (1988). A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika, 75(4), 800–802. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs HIL, Leritz EC, Williams VJ, Van Boxtel MPJ, van der Elst W, Jolles J, Verhey FRJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, & Salat DH (2013). Association between white matter microstructure, executive functioning, and processing speed in older adults: The impact of vascular health. Human Brain Mapping, 34(1), 10.1002/hbm.21412. 10.1002/hbm.21412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Wakana S, van Zijl PCM, Nagae-Poetscher LM (2005). MRI Atlas of Human White Matter (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology, 43(11), 2412–2412. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowrangi MA, & Rosenberg PB (2015). The Fornix in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 7, 1–7. 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possin KL, Moskowitz T, Erlhoff SJ, Rodgers KM, Johnson ET, Steele NZR, Higgins JJ, Stiver J, Alioto AG, Farias ST, Miller BL, & Rankin KP (2018). The Brain Health Assessment for detecting and diagnosing neurocognitive disorders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(1), 150–156. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton CE, Ukwuori GK, Flippini N, Mackay CE, & Ebmeier KP (2011). A meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 32(12), 2322.e5–2322.318. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranel D, Vianna E, Manzel K, Damasio H, & Grabowski T (2009). Neuroanatomical Correlates of the Benton Facial Recognition Test and Judgment of Line Orientation Test. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 31(2), 219–233. doi: 10.1080/13803390802317542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Vrooman HA, Wielopolski PA, Krestin GP, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, Van der Lugt A, & Breteler MM (2009). White matter microstructural integrity and cognitive function in a general elderly population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(60), 545–553. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Yushkevich PA, Alexander DC, & Gee JC (2006). Deformable registration of diffusion tensor MR images with explicit orientation optimization. Medical Image Analysis, 10(5), 764–785. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]