Abstract

Pluripotent stem cells can be isolated from embryos or derived by reprogramming. Pluripotency is stabilized by an interconnected network of pluripotency genes that cooperatively regulate gene expression. Here we describe the molecular principles of pluripotency gene function and highlight post-transcriptional controls, particularly those induced by RNA-binding proteins and alternative splicing, as an important regulatory layer of pluripotency. We also discuss heterogeneity in pluripotency regulation, alternative pluripotency states and future directions of pluripotent stem cell research.

Cells in the early embryo are deft at leaving their options open, yet have the ability to commit to a developmental path when appropriate cues are presented. Such developmental potential to become any cell type in the body is termed pluripotency. Pluripotent cells exist transiently during the first days of embryogenesis (up to E8.5)1. Pluripotency has been first confirmed in cell cultures of embryonic tumour cell lines2,3 and later in normal pluripotent stem cells (PSCs)4,5. PSCs can self-renew indefinitely in vitro and retain the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers of the body. The derivation of PSCs has afforded researchers a versatile tool to study the signalling environment of pluripotency, to dissect the molecular underpinning of pluripotency and to exploit the potential of these cells in disease modelling, drug discovery and regenerative medicine. Pluripotent cells in the early embryo provide the gold standard reference for comparison and validation of in vitro findings. In vivo populations, however, are scarce, which makes them challenging to study at the molecular level. Luckily, advances in single-cell, single-molecule and real-time molecular techniques have remedied this limitation and deepened our understanding of the intricate regulation of pluripotency.

In vivo and in vitro studies confirm that pluripotency is maintained by specific extrinsic signals and a hierarchical, interconnected gene network6. A few pluripotency transcription factors act as hubs of the pluripotency gene regulatory network (PGRN). The importance of these core transcription factors to pluripotency has been proven many times6–10, but perhaps most convincingly by the discovery that enforced expression of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and MYC can reinstate pluripotency in terminally differentiated cells11,12. The most salient points from studies on core pluripotency factors and the PGRN are that these factors regulate their targets co-operatively, form autoregulatory and feed-forward gene circuits, and that PGRNs exhibit bi-stability. In this case, pluripotency either propagates indefinitely when the core circuitry achieves balanced expression, or gives way to differentiation programs when the function of any of the core transcription factors is sufficiently diminished6,13–15.

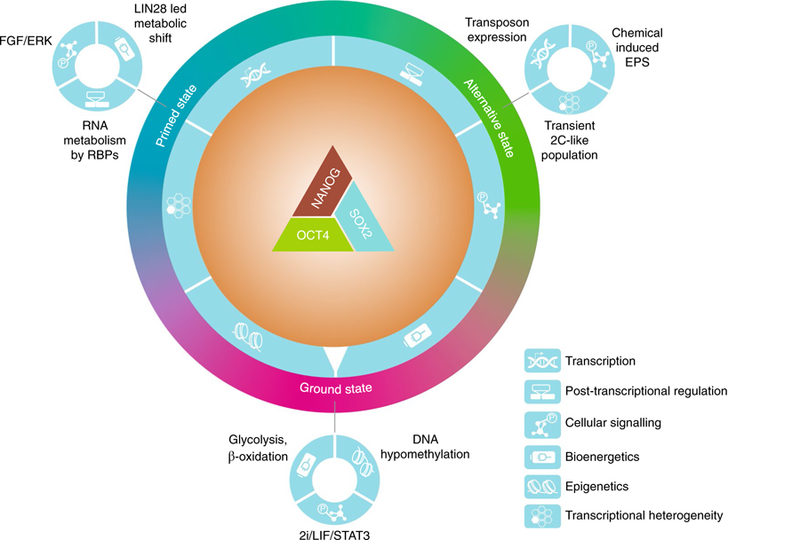

Besides transcriptional regulation, the PGRN also receives multiple layers of regulatory inputs, including post-transcriptional regulation of RNA processing, translation, protein modification and turnover, and epigenetic and metabolic regulation6 (Fig. 1). A recurring theme is that rather than relying on one monopolistic pathway, the PGRN often depends on antagonistic mechanisms to stabilize a dynamic, bi-stable pluripotent state that is poised for differentiation16,17. How these regulatory mechanisms operate is not completely understood. Here, we provide an up-to-date overview of the recent data on the molecular mechanisms underlying the multifaceted regulation of pluripotency.

Fig. 1. Core transcription factors and regulatory crosstalks of PGRN.

Pluripotency is stabilized by a triad of core transcription factors; namely OCT4, SOX2 and NANOG, which act cooperatively to regulate a larger and interconnected network of pluripotency genes. The PGRN crosstalks with multiple regulatory mechanisms, including transcription, post-transcriptional regulation, cellular signalling, bioenergetics, epigenetics and transcriptional heterogeneity (depicted with symbols on a dial outside of the core PGRN). For example, LIN28 is a PSC-associated RBP that mediates a metabolic shift from naïve to primed pluripotency by targeting mRNA translation, while the stability of LIN28 itself is controlled by fibroblast growth factor (FGF)–ERK signalling65. The integration of all regulatory inputs ultimately ‘dials’ PSCs in specific pluripotent states, such as the ground state, primed state and alternative pluripotency states. The primed, ground and alternative states are depicted as a colour spectrum because evidence suggests that in vivo pluripotency exists as a dynamic continuum and that these states are interconvertible in vitro.

In vivo, pluripotency exists within a relatively wide developmental window during which the transcriptional program changes substantially18. This process is mirrored by the in vitro stabilization of PSCs in a number of interconvertible pluripotent states, with distinct transcriptional and epigenetic features6,19. Several core pluripotency factors exhibit transcriptional heterogeneity in self-renewing culture20–25, implying that the PGRN might embrace heterogeneity as part of its regulatory assets (Fig. 1). We will discuss these findings and the diversity of pluripotency states in the final sections of this Review Article.

Core transcription factors of the PGRN

The core circuitry of the PGRN consists of three transcription factors, namely the octamer-binding OCT4, the SRY family transcription factor SOX2 and the homeobox transcription factor NANOG (refs 6,7,26). In vivo, OCT4 expression is evident in the pluripotent cells of the inner cell mass (ICM)—cells inside the blastocyst-stage embryo that contribute to all embryonic tissue—the epiblast and primordial germ cells8,27,28. OCT4 is uniformly expressed by all types of PSCs and is essential for pluripotency. It promotes mesendoderm differentiation of PSCs when overexpressed, whereas its downregulation leads to trophectoderm differentiation28,29. OCT4 is also the only reprogramming factor that is constant in most, if not all, transcription factor cocktails used to generate induced PSCs (iPSCs)30,31. SOX2 function is required for development of the pluripotent epiblast and for neural ectodermal differentiation of PSCs29,32. SOX2 and OCT4 form heterodimers and cooperatively regulate downstream targets, including each other33,34. Activation of the endogenous SOX2 gene is a rate-limiting step that allows the somatic-cell-reprogramming process to transition from the stochastic phase to the deterministic phase when cells become pluripotent35. NANOG is required in the ICM for formation of the epiblast10,36. Constitutive expression of NANOG enables leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF)-independent self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs)10,36. Together with OCT4 and SOX2, NANOG co-occupies most of its genomic targets, including core pluripotency factors and other pluripotency transcription factors, such as oestrogen-related receptor beta (ESRRB)37,38. NANOG, together with another pluripotency gene LIN28, can replace KLF4 and MYC in the original reprogramming cocktail to induce pluripotency39.

Genomic binding of pluripotency transcription factors.

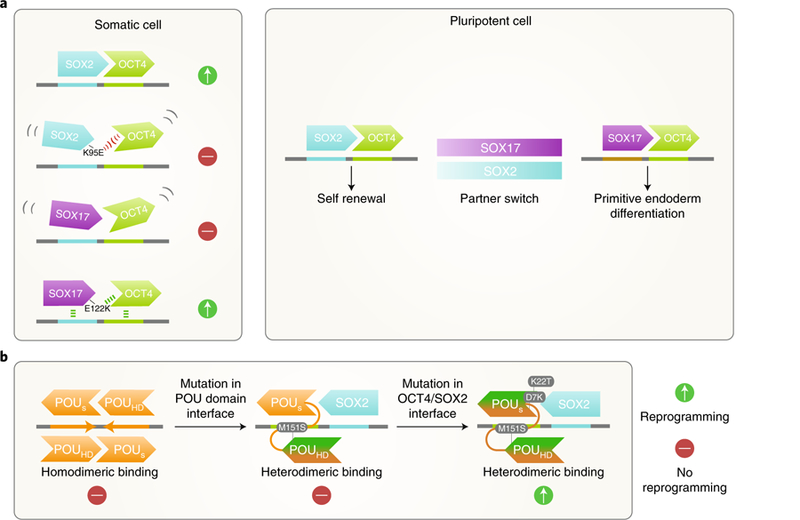

Co-operative binding of OCT4–SOX2 heterodimers is not only important for the maintenance of pluripotency but also for iPSC reprogramming. Changes in protein–protein interaction between OCT4 and SOX2 (by mutation or post-translational modification) and in the configuration of the OCT4–SOX2 composite DNA-binding motif greatly impact the expression of pluripotency and lineage genes6. Similarly, mutations in the OCT4–SOX2 contact region of OCT4, but not its DNA-binding domain, markedly compromise its reprogramming activity40,41. Some paralogues of these reprogramming factors substitute for them in reprogramming, probably due to shared DNA-binding motifs and protein partners, whereas others cannot31. These exceptions allow important insights into the molecular features of core pluripotency factors.

SOX17 has no reprogramming activity and cooperates poorly with OCT4 on the canonical OCT4–SOX2 motif42. Interestingly, a single amino acid change in the OCT4 interface of SOX17 enables efficient cooperation with OCT4 and converts it into a reprogramming factor42–45. Wild-type SOX17 can also cooperate with OCT4, but on an alternative DNA motif. Consequently, switching the OCT4 heterodimeric partner from SOX2 to SOX17 contributes to primitive endoderm differentiation42,44 (Fig. 2a). These findings suggest that cooperation between pluripotency factors greatly influences their genomic binding and thus their lineage-specifying activity.

Fig. 2. Cooperative binding of the core pluripotency transcription factors.

a, Key residues at the OCT4 interaction interface of SOX family transcription factors determine their ability to cooperatively bind with OCT4 and reprogram somatic cells to iPSCs. In PSCs, when the availability of SOX2 becomes limited, OCT4 can switch to partner with SOX17 and engage alternative heterodimeric motifs to promote differentiation. b, Other POU family members of OCT4, such as OCT6 (depicted in orange), prefer to homodimerize on the palindromic OCT–OCT motif. Mutagenesis of a key residue (M151S) in the interface between the POU-specific domain (POUs) and C-terminal POU homodomain (POUHD) of OCT6 redirects it to the heterodimeric OCT–SOX motif. Two additional mutations in the OCT4–SOX2 interaction interface in the POUs domain convert OCT6 into a reprogramming factor.

OCT4 is the only reprogramming factor that cannot be replaced by other members of the POU (Pit-Oct-Unc) family of transcription factors (for instance, OCT1, OCT6U or BRN5). Evidence suggests that OCT4 has a unique preference for the heterodimeric OCT4– SOX2 binding motif, whereas other POU factors preferentially bind palindromic octamer recognition elements as homodimers40,46. When amino acids that are important for such binding preferences are exchanged between OCT4 and OCT6, a neural POU factor without reprogramming potential, OCT4 loses a portion of its reprogramming activity40. Conversely, OCT6, with two additional mutations, gains the ability to generate iPSCs and maintain pluripotency in the absence of OCT4 (ref. 40) (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the function of specific POU factors in cell-fate determination depends on dimerization preference, which, in turn, is mediated by residues in the POU domains.

OCT4 is purported to be a so-called pioneer transcription factor that binds its target sequences despite hindrance by compact chromatin47. The pioneering function of OCT4 entails its ability to alter local chromatin structure and facilitate the binding of additional transcription factors such as SOX2 and NANOG (ref. 48). This function is important in the initialisation of new gene regulatory programs during cell-state transitions. How OCT4 performs this role at the molecular level has not been clear. A recent report showed that acute loss of OCT4 in mESCs leads to decreased chromatin accessibility in the majority of OCT4 binding sites49. Maintenance of chromatin accessibility of OCT4-binding-targets requires Brahma-related gene-1 (BRG1), a subunit of the BRG or Brahma-associated factor (BAF) complex, which is essential for maintenance of pluripotency. BRG1 is normally recruited to these sites by OCT4 (ref. 49). These data suggest a model whereby BRG1 creates accessible chromatin to stabilize the initial OCT4 binding, which facilitates more robust cooperative binding with SOX2 and NANOG (ref. 49). BRG1 enhances the efficiency of these reprogramming factors50. BRG1 is therefore probably also important for the pioneering function of OCT4 during reprogramming. Untangling OCT4-specific roles of BRG1 from its general effects on chromatin requires insights into the physical interaction between BRG1 and OCT4, and into mutations that disrupt BRG1 recruitment without affecting DNA binding of OCT4. Along these lines, mutations in the linker region between the two POU domains of OCT4 diminish its reprogramming activity but do not affect most of its fundamental functions40,51. Intriguingly, when the interactome of one such OCT4 mutation was compared with the published consensus, only two proteins, BRG1 and chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 4 (CHD4), showed statistically significant reduction in representation51.

Interestingly, a computational model that identifies transcription factor binding sites using DNase I hypersensitivity analysis, followed by sequencing, did not classify OCT4 as a pioneer factor52. However, this work analysed mESC differentiation rather than somatic cell reprogramming, and thus may not have adequately captured the pioneering function of OCT4. The pioneer model has also been challenged by findings in mouse somatic cell reprogramming, with reports that cooperative interactions among OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 initiate the inactivation of somatic enhancers53. In addition, selection of pluripotency enhancers in silent chromatin requires binding of multiple transcription factors53. Further study is warranted to understand the mechanisms by which pluripotency factors orchestrate reprogramming and their pioneer functions.

An OCT4-centric view on pluripotency-factor binding is certainly incomplete. Single-molecule tracking has demonstrated that SOX2 engages target DNA first, followed by facilitated binding of OCT4 (ref. 54). SOX2 or OCT4 rely on transient sampling, involving three-dimensional diffusion and one-dimensional sliding along DNA to find and engage in long-lived interactions with cognate DNA (ref. 54). Researchers have used photoactive fluorescence correlation spectroscopy to quantify the DNA-binding dynamics of SOX2 or OCT4 fused to photoactive green-fluorescent protein (paGFP–SOX2 or paGFP–OCT4) in single cells from live mouse embryos55. Results indicated that paGFP–SOX2 participates in more long-lived binding than paGFP–OCT4 in four-cell embryos55. The study suggested that long-lived SOX2-binding is variable among the four blastomeres and may predict the likeliness of cells contributing to the pluripotent ICM (ref. 55). This finding has shed some light on the controversy as to whether four-cell embryos harbour heterogeneities that can predict cell fate. However, the fact that endogenous levels of OCT4 and SOX2 in four-cell embryos are low and heterogeneous means that conclusions of the paGFP study have to be tempered55,56.

Most literature on pluripotency factors focuses on their function in the interphase of the cell cycle. Nonetheless, PSCs need to constantly progress through mitosis while maintaining pluripotency. How PSCs stably propagate the PGRN during mitosis, when chromosomes become highly condensed and transcription ceases, remains puzzling. Some transcription factors remain associated with mitotic chromatin and can potentially transmit tissue-specific transcriptional programs57,58. The orphan nuclear receptor ESRRB, a pluripotency factor that can substitute for NANOG, remains associated with the mitotic genome at 10–15% of its interphase target sites59. ESRRB mitotic binding sites tend to be associated with genes that are upregulated by ESRRB in G1 immediately after mitosis, including genes important for pluripotency (for example, TFCP2L1, TBX3, KLF4 and DNMT3L)59. These data suggest that mitotic binding of some pluripotency factors might be important for stable transmission of the PGRN through cell division. It would be interesting to examine if the core transcription factors OCT4 and SOX2 perform similar roles (NANOG is excluded from mitotic DNA).

Post-transcriptional controls

Post-transcriptional controls add another layer of regulation that serves to increase the flexibility and robustness of the PGRN (refs 6,7). RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) have emerged as central integrators of molecular events involving signalling, post-transcriptional gene control, metabolism and epigenetics60. Most RNAs in a cell exist as ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) together with RBPs60. RBPs regulate mRNA splicing, turnover, and translation, and cooperate with non-coding RNAs (ncRNA) in gene regulation60. Proteomic approaches have elucidated that the repertoire of RBPs in PSCs is more extensive than the number of proteins with recognizable RNA-binding domains (RBDs)61. Using UV cross-linking of RNPs followed by polyA+ RNA interactome capture, a team discovered 555 RBPs (283 novel ones) in mESCs61. Thirty-nine per cent of the RBPs have no known RBDs, suggesting novel structural bases for RNA interaction. More than half of the identified RBPs are enriched in PSCs. Interestingly, the mESC mRNA interactome overlaps with a MYC-centred regulatory network of the PGRN (refs 61,62). This finding suggests that many RBPs may participate in MYC-regulated processes, such as translation and proliferation in PSCs. Another report expanded the search to include polyA− ncRNAs using 4-thiouridine (4SU)-mediated photo-cross-linking and quantitative mass spectrometry63. In addition to peptide identification, covalently linking 4SU to peptides allows mapping of minimal RNA-binding regions (RBRs) of RBPs. This method, termed RBR-ID, resulted in identification of 803 RBPs in the nucleus of mESCs, over 50% of which were not known to be RBPs63. RBR mapping shows that, unexpectedly, RNA binding is common among chromatin regulators, of which many (for instance, EZH2, SUZ12, HP1, CTCF, HDAC1, DNMT3 and TET2) are involved in pluripotency regulation63. This finding further argues for an intimate link between protein–RNA interaction and epigenetic regulation.

LIN28 is a classic RBP that couples signalling with post-transcriptional control to specify cell fate64–67. LIN28 is an evolutionarily conserved RBP first identified in Caenorhabditis elegans as a regulator of developmental timing68. Both mammalian paralogues of LIN28 (LIN28A and LIN28B) are highly expressed in PSCs69. LIN28A is a reprogramming factor that can replace MYC, partly due to its analogous role in promoting cell division31,39. It promotes pluripotency by blocking biogenesis of the let-7 family of microR-NAs that are important for the differentiated phenotype70. LIN28 also binds and regulates translation of genes involved in the cell cycle, transcription and metabolism, independently of the LIN28–let-7 pathway67,71.

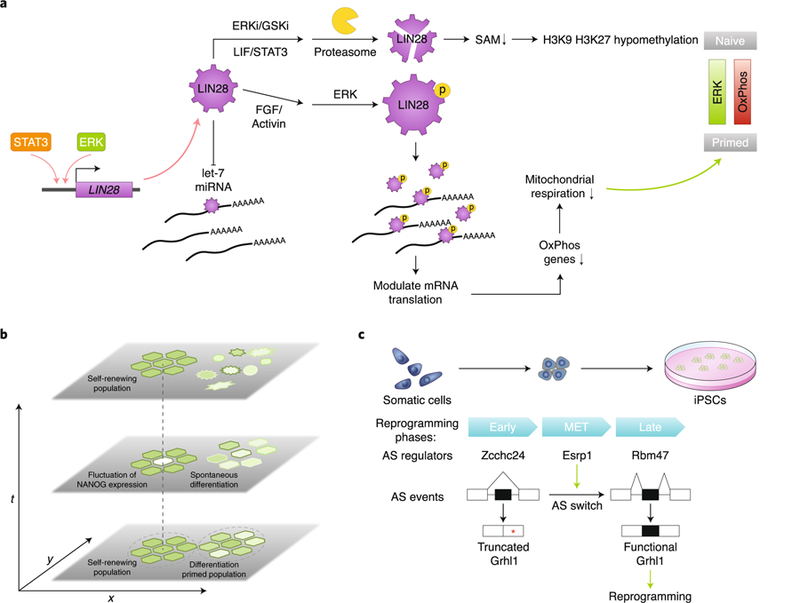

LIN28 protein stability is regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signalling, a key pathway controlling pluripotency6,64. Phosphorylation by ERK stabilizes LIN28 protein, thus shifting the stoichiometry between the RBP and its targets and enhancing the ability of LIN28 to control mRNA translation64. Interestingly, this phosphorylation effect is independent of the role of LIN28 in antagonizing let-7. In naïve pluripotency, LIN28 protein and RNA levels are reduced64. However, during the transition from naïve to primed pluripotency, increased fibroblast growth factor (FGF)–ERK signalling boosts LIN28 protein levels, which might facilitate a timely and robust cell-fate transition64 (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. The RNA-binding protein LIN28 plays key roles in pluripotency regulation.

a, LIN28 levels in PSCs are regulated at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. It opposes let-7 microRNA biogenesis and also has let-7 independent functions. LIN28 can coordinate upstream signalling and post-transcriptional control to regulate the metabolic and epigenetic state of PSCs. b, Transcriptional heterogeneity in PSCs manifests as transcriptional fluctuation over time, as seen in the case of NANOG. This is possibly caused by transcriptional noise and autoregulatory loops between pluripotency transcription factors. Heterogeneity in PSCs can also originate from subpopulation structure. For example, self-renewing PSCs can coexist with subpopulations of cells with reduced pluripotency gene expression and a higher propensity for differentiation over time. c, Multiphasic alternative splicing (AS) program changes during somatic cell reprogramming. Many AS regulators contribute to phase-specific AS changes during reprogramming, including Zcchc24 for the early phase, Esrp1 for the MET phase and Rbm47 for the late phase. Esrp1 promotes inclusion of an alternatively spliced exon in Grhl1, which produces a functional protein that facilitates MET rather than a truncated form. The full-length Grhl1 enhances reprogramming efficiency. Red asterisk, stop codon; OxPhos, oxidative phosphorylation; SAM, S-adenosyl-methionine.

Consequently, one of the effects of elevated LIN28 is a metabolic shift from naïve to primed pluripotency. Although both states feature higher reliance on glycolysis than oxidative phosphorylation compared to somatic cells72,73, naïve PSCs also use fatty acid beta-oxidation and have higher mitochondrial capacity74. LIN28 is upregulated in primed PSCs, both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally25,64, and binds mRNAs of genes important for oxidative phosphorylation to repress their protein abundance, thus lowering mitochondrial respiration in primed pluripotency65,73. Interestingly, LIN28-deficient iPSCs show reduced levels of metabolites in the one-carbon metabolic pathway, including S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM), the donor for histone methylation. Low availability of this donor in LIN28-knockout iPSCs correlates with H3K9 and H3K27 hypomethylation and a delayed exit from naïve pluripotency65. These observations show that LIN28 is well positioned to integrate upstream signalling, post-transcriptional control, metabolism and epigenetic regulation in cell fate determination (Fig. 3a). Although these studies provide a first glimpse into the RBP-based post-transcriptional regulatory network, a more complete understanding requires much more work. For example, LIF–STAT3 signalling upregulates mitochondrial transcription and promotes oxidative respiration, which is consistent with its critical role in naïve pluripotency75. STAT3 also binds the LIN28 promoter and upregulates its expression76. It is unclear whether crosstalk exists between these pathways to keep LIN28 function in balance. Furthermore, LIN28 is one of hundreds of RBPs in PSCs, most of which are uncharacterized. Further research on these RBPs will shed light on how widespread RBP-mediated coupling of signalling pathways and post-transcriptional regulation is.

Alternative splicing can increase proteome diversity and instigate alternative gene-expression programs during cell state transition77. Several pluripotency factors have been reported to function as PSC-specific isoforms78–80. Regulators of alternative splicing, including RBPs and splicing factors, control self-renewal of PSCs and cell reprogramming. Somatic cell reprogramming is a multi-step process with recognizable transitional phases when cells attain new transcriptional programs, such as mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) and transgene independence. An analysis of transcriptome-wide alternative splicing events during the time course of reprogramming using RNA sequencing revealed multiphasic and temporally complex changes in splicing. Many RBPs show a pattern of differential expression that correlates with changes in alternative splicing during reprogramming. This observation led to the identification of splicing factors that contribute to phase-specific alternative splicing changes, including Zcchc24 for the early phase, Rbm47 for the late phase, and Esrp1 for the MET phase81. Specifically, Esrp1-modulated splicing of epithelial transcription factor Grhl1 produces a functional protein that facilitates MET through inclusion of an exon that abolishes a downstream premature stop codon (Fig. 3c). Consistently, overexpression of Esrp1 or full-length Grhl1 enhances reprogramming efficiency81. These data highlight the complex and dynamic nature of the alternative splicing program in pluripotency acquisition. The functional significance of the large number of alternative splicing events is likely to fall on a broad spectrum. Detailed case-by-case studies combined with bioinformatics-guided candidate screening might be a logical path to insights into alternative splicing in pluripotency and strategies to enhance reprogramming.

Single-cell analysis resolves pluripotency heterogeneity

The idea that a dynamic and plastic transcriptional program is fundamental to pluripotency is supported by three types of evidence: first, PSCs exist in multiple interconvertible states with distinct transcriptional circuitry, signalling requirements and cellular phenotypes18,19,82–84. Second, naturally occurring subpopulations of PSCs differ in their developmental potency and propensity for differentiation into different lineages25,85,86. Third, several key regulators (for example, NANOG, ZFP42 and ESRRB) of the PGRN exhibit transcriptional heterogeneity25,87,88. Single-cell analysis is increasingly being used to deconstruct heterogeneity in biological systems to provide novel insights into the inner workings of gene networks. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) is widely accepted as a powerful tool for analysing the transcriptome of individual cells89. Single-cell quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization, and single-cell mass-cytometry90,91 are useful as complementary methods or secondary validation. Development of combinatorial single-cell multi-omics analysis offers unprecedented opportunity to correlate the transcriptome, genome, methylome and chromatin accessibility of a single cell to determine key nodes and causal relationships in gene networks92–97.

In vitro.

PSC heterogeneity can result from transcriptional fluctuation within cells over time, as suggested by studies of the NANOG, Rex1 and Stella loci20,21,87,98. These studies used a GFP reporter knocked into the pluripotency gene locus (or in a BAC transgene for Stella) to follow the transcriptional fluctuation of the locus in real time (Fig. 3b). They confirmed that the interactions between the core pluripotency factors and random fluctuation in transcriptional output yielded the observed behaviour of NANOG. However, others have suggested that the use of a fluorescent reporter may perturb the dynamic regulatory feedback of NANOG, which is exactly what the system is set out to measure, therefore defeating its purpose99,100. Nonetheless, scRNAseq studies show that NANOG transcripts do exhibit cell-to-cell variation, which is incidentally another source of heterogeneity indicative of the presence of subpopulations in culture25,88. The subpopulations of cells grown in LIF/serum conditions express varying levels of pluripotency and differentiation genes, which might correspond to distinct self-renewing and differentiation-primed populations (Fig. 3b). By comparison, pluripotency ground states (2i or alternative 2i conditions) show less transcriptional noise in pluripotency gene expression and no subpopulation of differentiating cells, consistent with the observation that ground-state cells are less prone to differentiation25,88. Surprisingly, removal of mature microRNAs drives PSCs into a low-noise ground state similar to the 2i condition, revealing that balanced expression of the opposing families of let-7 and miR-148/152 microRNAs controls ground state pluripotency25. scRNAseq also facilitates the study of a rare alternative pluripotent population expressing markers of the two-cell stage. These so-called 2C-like cells can be detected in the scRNAseq data despite their low frequency (~3% of analysed cells)88. Their characteristic MERVL expression was verified, but a closer similarity to two-cell stage embryos was not confirmed88.

In vivo.

Single-cell analysis indicates that in vivo pluripotent cells isolated from different stages of embryogenesis are more heterogeneous than PSCs in static in vitro culture88. Using scRNAseq to deconstruct the heterogeneity in the early embryo is extremely informative in understanding the in vivo dynamics of the PGRN and how exit of pluripotency and cell-fate determination are temporospatially coordinated. scRNAseq analysis of individual cells from human preimplantation embryos highlights an important difference in early lineage segregation and X chromosome inactivation between humans and mice. In humans, segregation of the three earliest cell lineages—trophectoderm (TE), epiblast (EPI) and primitive endoderm (PE)—happens simultaneously with blastocyst formation at E5 (ref. 101). This finding is in contrast with the two-step process thought to happen in mice, where PE and ICM are specified first, followed by the maturation of EPI and PE in the blastocyst102,103. A study also revealed gradual compensation of biallelic expression from X chromosomes in all three lineages during human preimplantation development, which again differs from X chromosome inactivation in mice101.

Although human ESCs (hESCs) are derived from preimplantation embryos, they share features with primed mouse epiblast stem cells rather than naïve mESCs19. Because of the basic research interest in pluripotency across evolutionarily divergent species, and in alternative PSC sources with practical advantages for single-cell cloning, genome editing and multilineage differentiation, capturing naïve pluripotency in hPSCs is a major ambition in the field. Multiple conditions have been proposed to stabilize naïve hPSCs in culture104–115. Most protocols share the mouse ground state condition (2i/LIF) as a starting point, but use different combination of chemical compounds, growth factors and transgenes to establish naïve hPSCs through conversion of conventional hESCs, repro-gramming of somatic cells or derivation from human embryos (Table 1). These protocols result in cells with different molecular and functional characteristics. A meta-analysis of the transcriptome of various naïve hPSC states and preimplantation embryos showed that naïve hPSCs established with different protocols display a high degree of variation in gene expression programs when compared to human blastocysts116. By contrast, ground state mouse PSCs shared a core gene network with mouse blastocyst embryos. Nonetheless, the established naïve hPSCs resembled human preimplantation embryos more than their primed counterparts or naïve mESCs116. Since it is not ethically permissible to perform chimaera assays in human embryos, several studies used interspecies chimaera assays as a functional test of naïve-state acquisition104,106,107. The results of these studies verify that the extent of naïve hPSC contribution to mouse embryos remains limited and controversial, partly due to the technical complexity of these experiments. To this end, non-human primate models have shown potential to address the species specificity of naïve pluripotency, and chimaera assays using naïve primate ESCs derived under analogous human naïve conditions could help optimize naïve hPSC culture117.

Table 1 |.

Summary of methods for induction of naïve and extended pluripotency

| Pluripotency state | Species | Culture condition | Genetic manipulation | Functional attributes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | Mouse | Serum/feeder; LIF/BMP4 | None. | X chromosome reactivation; high single-cell survival; germline chimaera contribution. | 4,5,15 |

| 2i: GSK3i (CHIR99021), MEKi (PD0325901) | None. | X chromosome reactivation; high single-cell survival; germline chimaera contribution. | 82 | ||

| Human | 2i/LIF/Forskolin | DOX inducible KLF4 and OCT4 or KLF2. | X chromosome reactivation; dome-shaped colonies; LIF dependent but TGFβ /ACTIVIN independent. | 112 | |

| NHSM containing optimized concentration of LIF, TGFβ 1, FGF2, ERK½i (PD0325901), GSK3β i (CHIR99021), JNKi (SP600125), p38i (SB203580), ROCKi (Y-27632) and PKCi (Go6983) | None. | X chromosome reactivation; high single-cell survival; shortened doubling time; DNA hypomethylation; contribution to cross-species chimaeric mouse embryos. | 106 | ||

| PD0325901/BIO/dorsomophin/LIF | None. | High single-cell survival; LIF dependent; higher expression of NANOG coincides with expression of GATA6. | 107 | ||

| Conversion: HDACi (sodium butyrate/SAHA), 2i/FGF2; derivation: 2i/FGF2 or 2i/FGFRi (SU5402)/LIF | None. | X chromosome reactivation; high single-cell survival; shortened doubling time; naïve-like mitochondrial morphology. | 110 | ||

| 5i/L/A: MEKi (PD0325901), GSK3i (IM12), BRAFi (SB590885), SRCi (WH-4–023), ROCKi (Y-27632), LIF, ACTIVIN | None. | X chromosome inactivation; high single-cell survival; proliferate slower than mESCs; uniform expression of NANOG; no contribution to inter-species chimaeric embryos; suitable for direct derivation of naïve hESCs from blastocysts; SSEA4–population loses blastocyst and germline epigenetic memory and imprinting. | 109, 113 | ||

| 2i/LIF/FGF2 | HERVH-driven transgenic GFP reporter. | X chromosome reactivation; higher single-cell clonality; elevated transcription of the primatespecific endogenous retrovirus HERVH. | 114 | ||

| t2iL+ Gö: 2i/LIF, PKCi (Gö6983) | Transient transgenic expression of NANOG and KLF2. | DNA hypomethylation; Naïvelike activation of mitochondrial respiration; incorporate into mouse preimplantation epiblast; suitable for direct derivation of naïve hESCs from ICM cells. | 108,115 | ||

| 2i/LIF/FGF2/Forskolin/Ascorbic acid | None. | Dome-shaped colonies; higher single-cell clonality; shortened doubling time; DNA hypomethylation; TGF-β/ACTIVIN independent. | 116 | ||

| Recombinant, truncated human NME7 termed NME7AB | None. | X chromosome reactivation; increased differentiation potential; high single-cell survival; shortened doubling time. | 117 | ||

| TL2i: 2i/LIF, tamoxifen | Enforced expression of a transgene STAT3-ER. | X chromosome inactivation; dome-shaped colonies; DNA hypomethylation; FGF2 independent; high single-cell survival. | 111 | ||

| Extended | Mouse | LIF/serum | tdTomato reporter with regulatory elements of the MuERV-L endogenous retrovirus | A rare and transient cell population; absent of the inner cell mass pluripotency proteins Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog; embryonic and extraembyonic lineage contributions. | 86 |

| 2i/LIF | Hex-Venus reporter. | A transient Hex+ ESC population coexpressing epiblast and extraembryonic genes; embryonic and extraembyonic lineage contributions. | 122 | ||

| ESPCM: hLIF, CHIR99021, PD0325901, JNK Inhibitor VIII, SB203580, A-419259, and XAV939 | Not necessary, although overexpression of axin1 in 2i/LIF ESCs confers expanded potential. | X chromosome reactivation; intermediate DNA methylation status compared to 2i/LIF and conventional ESCs; high 5hmC; single cells contribute to the embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages. | 126 | ||

| Mouse/human | LCDM: human LIF, CHIR99021, DiM ((S)-(+ )-dimethindene maleate), MiH (minocycline hydrochloride) | None. | Dome-shaped colonies; higher single-cell clonality; shortened doubling time; contribution to both embryonic and extraembryonic lineages in vivo; can derive mice through tetraploid complementation; interspecies chimaera competent. | 127 | |

| Human | Transient exposure to BMP4, inhibitors to Activin (A83–01) and FGF2 signaling (PD173074), then low FGF2 | None. | CDX2+, clonal expansion with trypsin, permissive for trophoblast development | 130 | |

| Conventional human ESC medium, DOX | DOX inducible BCL2L1 and BCL2 | Higher single cell cloning efficiency; lower levels of spontaneous apoptosis; contribute to interspecies chimaeras following injection into 4-cell mouse embryos; differentiate into embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages in mouse embryos. | 129 |

LIF, leukaemia inhibitory factor; DOX, doxycycline; 2i, the use of inhibitors of GSK3 (CHIR99021) and MAPK/ERK (PD0325901) signalling to maintain mESCs in the chemically defined 2i condition without extrinsic instruction.

Although naïve mouse PSCs and mouse embryos have been widely used as benchmarks for proposed human naïve conditions, it is unclear whether human in vivo naïve pluripotency is equivalent to that in the mouse. scRNAseq analysis of early and late human blastocysts discovered human-specific gene expression signatures of pluripotent cells in the ICM. Three signature genes (MCRS1, TET1 and THAP11) are able to induce human naïve pluripotency in vitro118. Similar work in non-human primates has extended the analysis to post-implantation development and revealed a developmental coordinate of the pluripotency spectrum among mice, monkeys and humans, which could lead to better culture conditions for hPSCs119.

An expanding view of in vitro pluripotency states

The diversity of pluripotency states that can be stabilised in culture is becoming increasingly appreciated. This variety is not surprising given the heterogeneity that exists among individual cells of the early embryo, from which PSCs are derived25,88,101,118. Evidence suggests that in vivo pluripotency exists as a dynamic continuum119. Improved knowledge of the PGRN and genetic and chemical screens have contributed to and expanded the list of pluripotent cell types, from the duet of naïve and primed PSCs to totipotent-like cells86,120 and distinct subtypes of primed PSCs83. Expression of distinct classes of transposable elements correlates with different early embryonic stages121. Evidence suggests that transposable elements have an important role in shaping the PGRN (ref. 6) Distinct classes of transposable elements are activated in the spectrum of PSC states. These states parallel the developmental continuum of pluripotency that is associated with a gradient of global DNA methylation122.

PSCs have limited ability to contribute to extraembryonic placental tissues in chimaeric embryos (embryos composed of cells that originated from more than one zygote)123. Although mESC subpopulations (such as 2C-like cells) can generate both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues, they cannot be stably maintained86,120. A cocktail of small molecules (Table 1) supports establishment of expanded potential stem cell (EPSC) cultures from eight-cell blastomeres, or conversion of existing mESCs and iPSCs124. These small molecules inhibit signalling by MAPK, Src, Wnt, Hippo and the poly-ADP-ribosylation (PARP) family members TNKS½, all of which regulate blastomere differentiation, particularly the segregation of trophectoderm and ICM (ref. 124). EPSCs contribute to embryonic and trophectoderm lineages at the single-cell level in chimaera assays. Whether the same condition applies to human blastomeres and hPSCs remains to be shown. Another group serendipitously discovered that a cocktail of chemicals (Table 1), initially identified for their role in supporting human naïve pluripotency, confer embryonic and extraembryonic bi-potential to mouse and hPSCs125. These cells, termed extended PSCs (EPS cells), show enhanced chimaeric contribution to the embryo proper and the placenta. In contrast to hPSCs, which have a poor ability to form interspecies chimaeras in preimplantation mouse embryos126, human EPS cells can form chimaeric mouse embryonic and extraembryonic tissues, albeit at very low levels. EPS cells are molecularly distinct from all other PSCs examined, including cells from early mouse embryos. The mechanistic underpinning of the chemical cocktail is not clear, but it seems to involve PARP1-mediated epigenetic regulation125. Additionally, manipulating trophoblast development and anti-apoptotic pathways in conventional hESCs also expands their extra-embryonic potential127,128.

Progression of the in vivo pluripotency continuum might be suspended in a reversible state called embryonic diapause, under unfavourable conditions129. This suspension of embryonic development occurs as the blastocyst delays implantation in the uterus. How in vivo pluripotent cells regulate this state is a fascinating question. Evidence suggests that partial inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) induces a diapause-like state in mouse blastocysts and extends their ex vivo culture from ~2 days to 22 days130. The ‘paused’ blastocysts are competent enough to give rise to ESCs and, more importantly, develop into live and fertile mice. Pausing can be induced in mESCs by blocking mTOR and can be sustained for weeks without cell death. Paused ESCs resume normal self-renewing growth when released from mTOR inhibition. Diapause and induced pausing are associated with reductions in mTOR activity, transcription, translation and epigenetic marks associated with active transcription130. As such, paused ESCs represent a new pluripotency state that is uniquely useful for studying how nutrient-sensing pathways regulate pluripotency, evolution of diapause and assisted reproduction.

Conclusions and outlook

As PSCs can become all cell types, research on them has touched every corner of biology. They have provided useful cellular models to gain a better molecular understanding of transcriptional, post-transcriptional, epigenetic and metabolic controls during cell fate transition. Many fundamental insights into gene regulation, such as super enhancers131 and topologically associating domains132, were discovered using these models. PSCs also offer unparalleled opportunities to study early development. Previously intractable questions relating to early human embryogenesis, placental development and diapause are being addressed thanks to the discovery of diverse pluripotency states. In the future, technological innovations, such as genome and epigenome editing133–136, single-cell multi-omics, CRISPR-based genomic tagging and live imaging will continue to elevate the precision and breadth of the investigation into the PGRN.

CRISPR–Cas9-mediated genome editing offers a powerful way to genetically label cells for lineage tracing to study regeneration137, map the complete lineage tree of the whole organism138, and perform genetic screens with single-cell precision to study barriers of reprogramming139. Imaging-based live cell tracing is enormously useful to monitor cell behaviour during differentiation in vitro or development in vivo. Various synthetic materials, including nanoparticles, have been used as non-invasive imaging reagents to not only observe cells (distribution, movement, morphology and more), but also assess their biological activity (viability and apoptosis)140,141. Within a cell, new technologies using CRISPR and catalytically inactive Cas9 to image genomic loci in live cells promise to improve the study of the spatiotemporal organization and dynamics of chromatin142. This system has been adapted for programmable tracking of endogenous RNA in live cells, thus opening up new possibilities of transcriptome manipulation in pluripotency143.

PSCs are among the most studied cell types using high-throughput-sequencing-based transcriptomic and epigenomic profiling techniques. These data were typically compared to a reference set using differential expression and clustering to learn gene regulatory programs in the cells of interest. Of late, computational models have been devised to systematically predict transcription factors necessary for cell fate transition144–147. These models use gene expression data of large collections of cell types, gene and protein network data, or mathematical control theory to build algorithms for cell fate control. Current models focus on making predictions of core transcription factors for transdifferentiation. In the future, we should be able to predict perturbations that can delete the epigenetic memory of the starting cell type and extinguish programs of unwanted cell fates.

The development of various alternative pluripotency states has opened up previously unrecognized avenues of research in developmental biology, evolutionary biology, and regenerative medicine. PSCs with enhanced ability to contribute to interspecies chimaeras, such as naïve PSCs and EPS cells, allow insights into the evolution of developmental timing, xenobarriers and cell–cell competition. Interspecies chimaeras between humans and non-primate mammals might be game changers in disease modelling, in vivo drug discovery, and xenogenic tissue or even organ generation148. One of the main challenges ahead is how to analyse the real-time changes in a single cell undergoing cell-fate transition. Here, CRISPR–Cas9 and computational tools are poised to propel the field forward. Quantitative descriptions along the temporal scale combined with the static multi-omic data could greatly improve our ability to predict stem cell behaviour. Knowing the developmental trajectory of PSCs might be a critical step toward the ultimate hope of regenerative medicine, to achieve de novo reconstruction of three-dimensional organs.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the colleagues whose works are not covered due to space constraint. We would like to thank May Schwarz, Peter Schwarz, Chunmei Xia and Xingxing Zhang for generous administrative help during the preparation of the manuscript. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose input has resulted in an improved manuscript. Work in the laboratory of M.L. was supported by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). Work in the laboratory of J.C.I.B. was supported by the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust (2012-PG-MED002), the Moxie Foundation, NIH (5 DP1 DK113616 and R21AG055938), Progeria Research Foundation, Fundacion Dr. Pedro Guillen and the Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang Y, Osorno R, Tsakiridis A & Wilson V In vivo differentiation potential of epiblast stem cells revealed by chimeric embryo formation. Cell Rep 2, 1571–1578 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal MD, Wishnow RM & Sato GH In vitro growth and differetiation of clonal populations of multipotential mouse clls derived from a transplantable testicular teratocarcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer I 44, 1001–1014 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finch BW & Ephrussi B Retention of multiple developmental potentialities by cells of a mouse testicular teratocarcinoma during prolonged culture in vitro and their extinction upon hybridization with cells of permanent lines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 57, 615–621 (1967). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans MJ & Kaufman MH Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 292, 154–156 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin GR Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 78, 7634–7638 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M & Belmonte JC Ground rules of the pluripotency gene regulatory network. Nat. Rev 18, 180–191 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng HH & Surani MA The transcriptional and signalling networks of pluripotency. Nat. Cell Biol 13, 490–496 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols J et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 95, 379–391 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masui S et al. Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct¾ expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol 9, 625–635 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitsui K et al. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell 113, 631–642 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K & Yamanaka S Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi K et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer LA et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 122, 947–956 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh YH et al. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet 38, 431–440 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AG et al. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature 336, 688–690 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shu J et al. Induction of pluripotency in mouse somatic cells with lineage specifiers. Cell 153, 963–975 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montserrat N et al. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts to pluripotency with lineage specifiers. Cell Stem Cell 13, 341–350 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Yamauchi T & Izpisua Belmonte JC An overview of mammalian pluripotency. Development 143, 1644–1648 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J & Izpisua Belmonte JC Dynamic pluripotent stem cell states and their applications. Cell Stem Cell 17, 509–525 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi K, Lopes SM, Tang F & Surani MA Dynamic equilibrium and heterogeneity of mouse pluripotent stem cells with distinct functional and epigenetic states. Cell Stem Cell 3, 391–401 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalmar T et al. Regulated fluctuations in nanog expression mediate cell fate decisions in embryonic stem cells. PLoS Biol 7, e1000149 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacArthur BD et al. Nanog-dependent feedback loops regulate murine embryonic stem cell heterogeneity. Nat. Cell Biol 14, 1139–1147 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karwacki-Neisius V et al. Reduced Oct4 expression directs a robust pluripotent state with distinct signaling activity and increased enhancer occupancy by Oct4 and Nanog. Cell Stem Cell 12, 531–545 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds N et al. NuRD suppresses pluripotency gene expression to promote transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell 10, 583–594 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar RM et al. Deconstructing transcriptional heterogeneity in pluripotent stem cells. Nature 516, 56–61 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young RA Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell 144, 940–954 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scholer HR, Hatzopoulos AK, Balling R, Suzuki N & Gruss P A family of octamer-specific proteins present during mouse embryogenesis: evidence for germline-specific expression of an Oct factor. EMBO J 8, 2543–2550 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niwa H, Miyazaki J & Smith AG Quantitative expression of Oct-¾ defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat. Genet 24, 372–376 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomson M et al. Pluripotency factors in embryonic stem cells regulate differentiation into germ layers. Cell 145, 875–889 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi K & Yamanaka S A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 17, 183–193 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M & Izpisua Belmonte JC Looking to the future following 10 years of induced pluripotent stem cell technologies. Nat. Protoc 11, 1579–1585 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avilion AA et al. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Gen. Dev 17, 126–140 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chew JL et al. Reciprocal transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1 and Sox2 via the Oct4/Sox2 complex in embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Bio 25, 6031–6046 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodda DJ et al. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J. Biol. Chem 280, 24731–24737 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buganim Y et al. Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell 150, 1209–1222 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chambers I et al. Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell 113, 643–655 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell 133, 1106–1117 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Festuccia N et al. Esrrb is a direct Nanog target gene that can substitute for Nanog function in pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell 11, 477–490 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jerabek S et al. Changing POU dimerization preferences converts Oct6 into a pluripotency inducer. EMBO Rep 18, 319–333 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tapia N et al. Dissecting the role of distinct OCT4-SOX2 heterodimer configurations in pluripotency. Sci. Rep 5, 13533 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jauch R et al. Conversion of Sox17 into a pluripotency reprogramming factor by reengineering its association with Oct4 on DNA. Stem Cells 29, 940–951 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng CK et al. Deciphering the Sox-Oct partner code by quantitative cooperativity measurements. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 4933–4941 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aksoy I et al. Oct4 switches partnering from Sox2 to Sox17 to reinterpret the enhancer code and specify endoderm. EMBO J 32, 938–953 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aksoy I et al. Sox transcription factors require selective interactions with Oct4 and specific transactivation functions to mediate reprogramming. Stem Cells 31, 2632–2646 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mistri TK et al. Selective influence of Sox2 on POU transcription factor binding in embryonic and neural stem cells. EMBO Rep 16, 1177–1191 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaret KS & Carroll JS Pioneer transcription factors: establishing competence for gene expression. Gen. Dev 25, 2227–2241 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soufi A, Donahue G & Zaret KS Facilitators and impediments of the pluripotency reprogramming factors’ initial engagement with the genome. Cell 151, 994–1004 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King HW & Klose RJ The pioneer factor OCT4 requires the chromatin remodeller BRG1 to support gene regulatory element function in mouse embryonic stem cells. eLife 6, e22631 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singhal N et al. Chromatin-remodeling components of the BAF complex facilitate reprogramming. Cell 141, 943–955 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esch D et al. A unique Oct4 interface is crucial for reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat. Cell Biol 15, 295–301 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherwood RI et al. Discovery of directional and nondirectional pioneer transcription factors by modeling DNase profile magnitude and shape. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 171–178 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chronis C et al. Cooperative binding of transcription factors orchestrates reprogramming. Cell 168, 442–459 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J et al. Single-molecule dynamics of enhanceosome assembly in embryonic stem cells. Cell 156, 1274–1285 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White MD et al. Long-lived binding of Sox2 to DNA predicts cell fate in the four-cell mouse embryo. Cell 165, 75–87 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dietrich JE & Hiiragi T Stochastic patterning in the mouse preimplantation embryo. Development 134, 4219–4231 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kadauke S et al. Tissue-specific mitotic bookmarking by hematopoietic transcription factor GATA1. Cell 150, 725–737 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caravaca JM et al. Bookmarking by specific and nonspecific binding of FoxA1 pioneer factor to mitotic chromosomes. Gen. Dev 27, 251–260 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Festuccia N et al. Mitotic binding of Esrrb marks key regulatory regions of the pluripotency network. Nat. Cell Biol 18, 1139–1148 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Konig J, Zarnack K, Luscombe NM & Ule J Protein-RNA interactions: new genomic technologies and perspectives. Nat. Rev 13, 77–83 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwon SC et al. The RNA-binding protein repertoire of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 20, 1122–1130 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim J et al. A Myc network accounts for similarities between embryonic stem and cancer cell transcription programs. Cell 143, 313–324 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.He C et al. High-resolution mapping of RNA-binding regions in the nuclear proteome of embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell 64, 416–430 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsanov KM et al. LIN28 phosphorylation by MAPK/ERK couples signalling to the post-transcriptional control of pluripotency. Nat. Cell Biol 19, 60–67 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang J et al. LIN28 regulates stem cell metabolism and conversion to primed pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 19, 66–80 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu B, Zhang K & Huang Y Lin28 modulates cell growth and associates with a subset of cell cycle regulator mRNAs in mouse embryonic stem cells. RNA 15, 357–361 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peng S et al. Genome-wide studies reveal that Lin28 enhances the translation of genes important for growth and survival of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 29, 496–504 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moss EG, Lee RC & Ambros V The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell 88, 637–646 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shyh-Chang N & Daley GQ Lin28: primal regulator of growth and metabolism in stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 12, 395–406 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Viswanathan SR, Daley GQ & Gregory RI Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science 320, 97–100 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parisi S et al. Lin28 is induced in primed embryonic stem cells and regulates let-7-independent events. FASEB J 31, 1046–1058 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Daley GQ, Koehler CM & Teitell MA Metabolic regulation in pluripotent stem cells during reprogramming and self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 11, 589–595 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Folmes CD et al. Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab 14, 264–271 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sperber H et al. The metabolome regulates the epigenetic landscape during naive-to-primed human embryonic stem cell transition. Nat. Cell Biol 17, 1523–1535 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carbognin E, Betto RM, Soriano ME, Smith AG & Martello G Stat3 promotes mitochondrial transcription and oxidative respiration during maintenance and induction of naive pluripotency. EMBO J 35, 618–634 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo L et al. Stat3-coordinated Lin-28-let-7-HMGA2 and miR-200-ZEB1 circuits initiate and maintain oncostatin M-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 32, 5272–5282 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kalsotra A & Cooper TA Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nat. Rev 12, 715–729 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salomonis N et al. Alternative splicing regulates mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10514–10519 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gabut M et al. An alternative splicing switch regulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell 147, 132–146 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Das S, Jena S & Levasseur DN Alternative splicing produces Nanog protein variants with different capacities for self-renewal and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem 286, 42690–42703 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cieply B et al. Multiphasic and dynamic changes in alternative splicing during induction of pluripotency are coordinated by numerous RNA-binding proteins. Cell Rep 15, 247–255 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ying QL et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature 453, 519–523 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu J et al. An alternative pluripotent state confers interspecies chimaeric competency. Nature 521, 316–321 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brons IG et al. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 448, 191–195 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klein AM et al. Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell 161, 1187–1201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Macfarlan TS et al. Embryonic stem cell potency fluctuates with endogenous retrovirus activity. Nature 487, 57–63 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chambers I et al. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature 450, 1230–1234 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kolodziejczyk AA et al. Single cell RNA-sequencing of pluripotent states unlocks modular transcriptional variation. Cell Stem Cell 17, 471–485 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu AR, Wang J, Streets AM & Huang Y Single-cell transcriptional analysis. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 10, 439–462 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zunder ER, Lujan E, Goltsev Y, Wernig M & Nolan GP A continuous molecular roadmap to iPSC reprogramming through progression analysis of single-cell mass cytometry. Cell Stem Cell 16, 323–337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lujan E et al. Early reprogramming regulators identified by prospective isolation and mass cytometry. Nature 521, 352–356 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Angermueller C et al. Parallel single-cell sequencing links transcriptional and epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat. Methods 13, 229–232 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dey SS, Kester L, Spanjaard B, Bienko M & van Oudenaarden A Integrated genome and transcriptome sequencing of the same cell. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 285–289 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guo F et al. Single-cell multi-omics sequencing of mouse early embryos and embryonic stem cells. Cell Res 27, 967–988 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hou Y et al. Single-cell triple omics sequencing reveals genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinomas. Cell Res 26, 304–319 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hu Y et al. Simultaneous profiling of transcriptome and DNA methylome from a single cell. Genome Biol 17, 88 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Macaulay IC et al. G&T-seq: parallel sequencing of single-cell genomes and transcriptomes. Nat. Methods 12, 519–522 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, Murakami K, Takahashi K & Niwa H Identification and characterization of subpopulations in undifferentiated ES cell culture. Development 135, 909–918 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Smith RCG et al. Nanog fluctuations in embryonic stem cells highlight the problem of measurement in cell biology. Biophys. J 112, 2641–2652 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Faddah DA et al. Single-cell analysis reveals that expression of nanog is biallelic and equally variable as that of other pluripotency factors in mouse ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 13, 23–29 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Petropoulos S et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals lineage and X chromosome dynamics in human preimplantation embryos. Cell 165, 1012–1026 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cockburn K & Rossant J Making the blastocyst: lessons from the mouse. J. Clin. Invest 120, 995–1003 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yamanaka Y, Lanner F & Rossant J FGF signal-dependent segregation of primitive endoderm and epiblast in the mouse blastocyst. Development 137, 715–724 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gafni O et al. Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature 504, 282–286 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chan YS et al. Induction of a human pluripotent state with distinct regulatory circuitry that resembles preimplantation epiblast. Cell Stem Cell 13, 663–675 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Takashima Y et al. Resetting transcription factor control circuitry toward ground-state pluripotency in human. Cell 158, 1254–1269 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Theunissen TW et al. Systematic identification of culture conditions for induction and maintenance of naive human pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 15, 471–487 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ware CB et al. Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4484–4489 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chen H et al. Reinforcement of STAT3 activity reprogrammes human embryonic stem cells to naive-like pluripotency. Nat. Commun 6, 7095 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hanna J et al. Human embryonic stem cells with biological and epigenetic characteristics similar to those of mouse ESCs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9222–9227 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pastor WA et al. Naive human pluripotent cells feature a methylation landscape devoid of blastocyst or germline memory. Cell Stem Cell 18, 323–329 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang J et al. Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus-driven transcription defines naive-like stem cells. Nature 516, 405–409 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Guo G et al. Naive pluripotent stem cells derived directly from isolated cells of the human inner cell mass. Stem Cell Rep 6, 437–446 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Duggal G et al. Alternative routes to induce naive pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 33, 2686–2698 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Carter MG et al. A primitive growth factor, NME7AB, is sufficient to induce stable naive state human pluripotency; reprogramming in this novel growth factor confers superior differentiation. Stem Cells 34, 847–859 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Huang K, Maruyama T & Fan G The naive state of human pluripotent stem cells: a synthesis of stem cell and preimplantation embryo transcriptome analyses. Cell Stem Cell 15, 410–415 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen Y et al. Generation of cynomolgus monkey chimeric fetuses using embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 17, 116–124 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Durruthy-Durruthy J et al. Spatiotemporal reconstruction of the human blastocyst by single-cell gene-expression analysis informs induction of naive pluripotency. Dev. Cell 38, 100–115 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nakamura T et al. A developmental coordinate of pluripotency among mice, monkeys and humans. Nature 537, 57–62 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Morgani SM et al. Totipotent embryonic stem cells arise in ground-state culture conditions. Cell Rep 3, 1945–1957 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Goke J et al. Dynamic transcription of distinct classes of endogenous retroviral elements marks specific populations of early human embryonic cells. Cell Stem Cell 16, 135–141 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hackett JA, Kobayashi T, Dietmann S & Surani MA Activation of lineage regulators and transposable elements across a pluripotent spectrum. Stem Cell Rep 8, 1645–1658 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Beddington RS & Robertson EJ An assessment of the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells in the midgestation mouse embryo. Development 105, 733–737 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yang J et al. Establishment of mouse expanded potential stem cells. Nature 550, 393–397 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yang Y et al. Derivation of pluripotent stem cells with in vivo embryonic and extraembryonic potency. Cell 169, 243–257 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mascetti VL & Pedersen RA Human-mouse chimerism validates human stem cell pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 18, 67–72 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang X et al. Human embryonic stem cells contribute to embryonic and extraembryonic lineages in mouse embryos upon inhibition of apoptosis. Cell Res 28, 126–129 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yang Y et al. Heightened potency of human pluripotent stem cell lines created by transient BMP4 exposure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2337–2346 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fenelon JC, Banerjee A & Murphy BD Embryonic diapause: development on hold. Int. J. Dev. Biol 58, 163–174 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bulut-Karslioglu A et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces a paused pluripotent state. Nature 540, 119–123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Whyte WA et al. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153, 307–319 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dixon JR et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li M et al. Efficient correction of hemoglobinopathy-causing mutations by homologous recombination in integration-free patient iPSCs. Cell Res 21, 1740–1744 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Li M, Suzuki K, Kim NY, Liu GH & Izpisua Belmonte JC A cut above the rest: targeted genome editing technologies in human pluripotent stem cells. J. Biol. Chem 289, 4594–4599 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Suzuki K et al. In vivo genome editing via CRISPR-Cas9 mediated homology-independent targeted integration. Nature 540, 144–149 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Takahashi Y et al. Integration of CpG-free DNA induces de novo methylation of CpG islands in pluripotent stem cells. Science 356, 503–508 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Flowers GP, Sanor LD & Crews CM Lineage tracing of genome-edited alleles reveals high fidelity axolotl limb regeneration. eLife 6, e25726 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.McKenna A et al. Whole-organism lineage tracing by combinatorial and cumulative genome editing. Science 353, aaf7907 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Michlits G et al. CRISPR-UMI: single-cell lineage tracing of pooled CRISPR–Cas9 screens. Nat. Methods 14, 1191–1197 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Schroeder T Imaging stem-cell-driven regeneration in mammals. Nature 453, 345–351 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lee SK, Mortensen LJ, Lin CP & Tung CH An authentic imaging probe to track cell fate from beginning to end. Nat. Commun 5, 5216 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Chen B, Guan J & Huang B Imaging specific genomic DNA in living cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys 45, 1–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nelles DA et al. Programmable RNA tracking in live cells with CRISPR/ Cas9. Cell 165, 488–496 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Cahan P et al. CellNet: network biology applied to stem cell engineering. Cell 158, 903–915 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.D’Alessio AC et al. A systematic approach to identify candidate transcription factors that control cell identity. Stem Cell Rep 5, 763–775 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Rackham OJ et al. A predictive computational framework for direct reprogramming between human cell types. Nat. Genet 48, 331–335 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ronquist S et al. Algorithm for cellular reprogramming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11832–11837 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wu J et al. Interspecies chimerism with mammalian pluripotent stem cells. Cell 168, 473–486 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]