Abstract

Background

161Tb is an interesting radionuclide for cancer treatment, showing similar decay characteristics and chemical behavior to clinically-employed 177Lu. The therapeutic effect of 161Tb, however, may be enhanced due to the co-emission of a larger number of conversion and Auger electrons as compared to 177Lu. The aim of this study was to produce 161Tb from enriched 160Gd targets in quantity and quality sufficient for first application in patients.

Methods

No-carrier-added 161Tb was produced by neutron irradiation of enriched 160Gd targets at nuclear research reactors. The 161Tb purification method was developed with the use of cation exchange (Sykam resin) and extraction chromatography (LN3 resin), respectively. The resultant product (161TbCl3) was characterized and the 161Tb purity compared with commercial 177LuCl3. The purity of the final product (161TbCl3) was analyzed by means of γ-ray spectrometry (radionuclidic purity) and radio TLC (radiochemical purity). The radiolabeling yield of 161Tb-DOTA was assessed over a two-week period post processing in order to observe the quality change of the obtained 161Tb towards future clinical application. To understand how the possible drug products (peptides radiolabeled with 161Tb) vary with time, stability of the clinically-applied somatostatin analogue DOTATOC, radiolabeled with 161Tb, was investigated over a 24-h period. The radiolytic stability experiments were compared to those performed with 177Lu-DOTATOC in order to investigate the possible influence of conversion and Auger electrons of 161Tb on peptide disintegration.

Results

Irradiations of enriched 160Gd targets yielded 6–20 GBq 161Tb. The final product was obtained at an activity concentration of 11–21 MBq/μL with ≥99% radionuclidic and radiochemical purity. The DOTA chelator was radiolabeled with 161Tb or 177Lu at the molar activity deemed useful for clinical application, even at the two-week time point after end of chemical separation. DOTATOC, radiolabeled with either 161Tb or 177Lu, was stable over 24 h in the presence of a stabilizer.

Conclusions

In this study, it was shown that 161Tb can be produced in high activities using different irradiation facilities. The developed method for 161Tb separation from the target material yielded 161TbCl3 in quality suitable for high-specific radiolabeling, relevant for future clinical application.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s41181-019-0063-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 161Tb, Auger/conversion electrons, Purification method, Somatostatin analogues, DOTA

Background

The use of the β−–emitter 177Lu (Eβ-av = 134 keV (100%), T1/2 = 6.7 d) (Solá 2000), in combination with somatostatin analogues (e.g. DOTATOC, DOTATATE), is considered a promising tool for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors (NET). It has been extensively utilized in clinics, which recently resulted in the approval of Lutathera® (177Lu-DOTATATE), by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Kam 2012; CHMP 2016). Treatment with 177Lu-DOTATATE resulted in longer progression-free survival time (65.2% at Month 20, compared to 10.8% in the control group); nevertheless, partial remission remained at ≤50% in the assessable patients, with the complete response being ≤12% (CHMP 2016; Strosberg 2017; Kwekkeboom 2005; van Essen 2007; Sansovini 2013). The radiolanthanide 161Tb shows similar decay characteristics (Eβ-av = 154 keV (100%), T1/2 = 6.9 d (Solá 2000)) and coordination chemistry to 177Lu. 161Tb can, therefore, be stably coordinated with a DOTA chelator and be used in combination with a number of small molecules, peptides and antibodies currently employed with 177Lu. 161Tb may show an increased therapeutic efficacy over 177Lu, due to the co-emission of a substantially larger number of conversion and Auger electrons at a favorable energy range (~12 e−, ~36 keV per decay for 161Tb and ~ 1 e−, ~ 1.0 keV per decay for 177Lu, respectively) (Eckerman 2008; Müller 2014). The possibility of using 161Tb as an alternative to 177Lu was first proposed by Lehenberger et al. (Lehenberger 2011) and, subsequently, corroborated by Müller et al. by comparison of in vitro and in vivo studies using a DOTA-folate conjugate labeled with 161Tb and 177Lu (Müller 2014). The enhanced anti-tumor effect, as well as higher average survival time, was found in mice treated with 161Tb-folate over those which received 177Lu-folate. In a preliminary therapy study using 161Tb-PSMA-617, PSMA-positive PC-3 PIP tumor-bearing mice demonstrated significant tumor-growth delay, as compared to the control group, without causing early side effects (Müller 2018a). Better therapeutic efficacy was also observed for a 161Tb-labeled radioimmunoconjugate in an ovarian cancer model when compared to the 177Lu-radioimmunoconjugate counterpart (Grünberg 2014). The low-energy conversion and Auger electron emission from 161Tb contribute 26% – 88% to the total absorbed dose (compared to 10% – 34% for 177Lu), depending on the tumor size, which could be associated to its enhanced therapeutic efficacy over that of 177Lu (Champion 2016). The doses delivered by 161Tb or 177Lu to 10 mm-diameter spheres were calculated to be comparable for both radionuclides, however, for 100 μm-diameter and 10 μm-diameter spheres 161Tb could deliver 1.8 and 3.6 times higher dose than 177Lu, respectively, making 161Tb the more appropriate candidate for treating micrometastases (Hindie 2016). Also, the co-emission of 48.9 keV and 74.6 keV 161Tb γ-rays allows for the acquisition of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) images for dosimetry determination before administration of the therapeutic dose, comparable to that performed with 177Lu (Marin 2018). In addition, 161Tb could be used in combination with diagnostic radioisotopes, namely, 152Tb (PET) or 155Tb (SPECT) as a matched pair towards the concept of theragnostics (Müller 2012; Müller 2018b).

The 161Tb production route was proposed by Lehenberger et al. via the 160Gd(n,γ)161Gd → 161Tb nuclear reaction, which provided no-carrier-added radiolanthanide at high specific activities (~ 4 TBq/mg) (Lehenberger 2011). Enriched 160Gd(NO3)3 targets (ampoules) were prepared by dissolving 160Gd2O3 in nitric acid and evaporating to dryness. Lanthanide nitrates are hygroscopic materials, however, and the heating of the ampoule in the nuclear reactor (due to γ-rays from the reactor and β -rays generated in the sample) can create water vapor within the ampoule. The vapor could create overpressure, resulting in ampoule breakage. The 161Tb separation method from 160Gd(NO3)3 targets was previously developed at Paul Scherrer Institute (Villigen-PSI, Switzerland), but the radiolabeling capability of the 161Tb product was three times lower than the commercial no-carrier-added 177Lu (Lehenberger 2011). This implied that the 161Tb product contained undesired environmental impurities at the end of separation (EOS), thereby, compromising the capability of reproducible routine production.

Herein, we report on the large-scale 161Tb production from 160Gd2O3 target material, suitable for introduction into a process in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and, thereafter, clinical application. The 161Tb purification method was improved by optimization of the Tb/Gd separation process, followed by characterization of the final product (161TbCl3). The 161Tb purity was compared with no-carrier-added 177Lu (EndolucinBeta), as currently produced by ITG GmbH, Germany, for worldwide clinical application.

Methods

Target preparation for the production of 161Tb

Gadolinium oxide (160Gd2O3, 98.2% enrichment, Isoflex, USA) was used as target material for the production of no-carrier-added 161Tb, as previously reported (Lehenberger 2011). The elemental composition of the target material in question is provided in the Supplementary Material (Table S1). To prepare the targets for irradiation at the spallation-induced neutron source (SINQ, Paul Scherrer Institute, 4.1013 n.cm− 2.s− 1), 80–95 mg 160Gd(NO3)3 were placed in a quartz glass ampoule (Suprasil, Heraeus, Germany) and sealed. Ampoules containing 7–33 mg 160Gd2O3 were prepared in a similar manner and sent for irradiation to two research nuclear reactors (SAFARI-1, South African Nuclear Energy Corporation, 2.1014 n.cm− 2.s− 1; and RHF ILL, Institut Laue–Langevin, 1.1015 n.cm− 2.s− 1). The mass of the target material, required for the irradiation at the chosen facility, was calculated using the ChainSolver code (Romanov 2005).

Determination of the neutron fluxes of the irradiation facilities with 59Co monitors

In order to monitor neutron fluxes at ILL, SAFARI-1 and SINQ, quartz ampoules containing 59Co as standard (59Co in 2% w/w HNO3, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) with 33 ng – 2 μg 59Co (mass determined based on the volume of the standard solution pipetted) were prepared. Ampoules were dried at 80 °C, to ensure water evaporation, and sealed. Ampoules with 59Co standard were placed and sealed in the same Al container as the ampoules containing 160Gd target material, along with empty ampoules (used as references) for the irradiation process. 59Co masses were calculated to produce 50–100 kBq 60Co activity via 59Co(n,γ)60Co nuclear reaction, depending on the reactor neutron flux. The 60Co activities in the ampoules were measured after irradiations using a high-purity germanium (HPGe) detector (Canberra, France), in combination with the InterWinner software package (version 7.1, Itech Instruments, France), with a statistical uncertainty less than 5%. After irradiation at the facility in question and gamma spectrometry of the ampoules, the activities of 60Co produced by the added 59Co standards were determined by subtraction of the 60Co activities of the reference (empty) ampoules which stem from traces of cobalt impurities in the used quartz. Based on these 60Co activity values, the average neutron flux (ϕth) of each irradiation was calculated (Table 1) using the following equation:

| 1 |

where A0 is the 60Co activity at the end of bombardment, σn the thermal neutron capture cross section (37.18 ± 0.06 b (Mughabghab 2018)), N the number of target atoms, λ the radioactive decay constant and tB the irradiation time.

Table 1.

Measured neutron fluxes of the irradiation facilities used for 161Tb production

| Facility | Irradiation time, d | 60Co activity, kBq | Measured perturbed neutron flux, n.cm− 2.s− 1 | Nominal unperturbed neutron flux, n.cm− 2.s− 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILL | 10 | 33.5 | 7.4·1014 | 1.0·1015 |

| SAFARI-1 | 13–16 | 41.0–54.0 | 1.8·1014 | 2.0·1014 |

| SINQ | 21 | 92.3 | 1.8·1013 a | 4.0·1013 |

aMeasurement performed while spallation target was operated at lower than optimum beam current

Development of the procedure for the 161Tb purification process

A chromatographic column (10 mm × 170 mm) was prepared using Sykam macroporous cation exchange resin (Sykam Chromatographie Vertriebs GmbH, Germany; particle size 12–22 μm, NH4+ form). The separation parameters were first optimized by means of bench experiments with the use of radioactive tracers (Additional file 1: Table S2) and subsequently applied towards the separation of an aliquot of reactor-produced 161Tb (230 MBq). These experiments resulted in the design and construction of a chemical separation module, such that high activities (GBq) of the radionuclide can be processed in the hot cell. The quartz glass ampoule with the 160Gd2O3 target material, delivered from the irradiation facility, was placed in a plastic target tube, crushed and attached to the module inside the hot cell with the aid of manipulators. The target material from the ampoule was dissolved in 2.0 mL 7.0 M nitric acid (HNO3, Suprapur, Merck, Germany), followed by evaporation at 80 °C under nitrogen flow. The residue was taken up in 0.1 M ammonium nitrate (prepared from 25% Suprapur NH3 and 65% Suprapur HNO3, Merck, Germany) and loaded onto the cation exchange resin column. The 161Tb separation from the target material and impurities was performed with the use of 0.13 M (pH 4.5) α-hydroxy-isobutyric acid (α-HIBA, Sigma-Aldrich GmbH, Germany) as eluent. Concentration of 161Tb was performed using the bis(2,4,4-trimethyl-1-pentyl) phosphinic acid extraction resin (LN3, Triskem International, France; 6 mm × 5 mm), followed by the elution of the final product (161TbCl3) in 500 μL 0.05 M hydrochloric acid (HCl, Suprapur, Merck, Germany). The pH of the final product was determined using pH indicator strips (Merck, Germany).

Characterization of the 161Tb product after purification

Radionuclidic purity

The identification and radionuclidic purity of the 161Tb were examined by γ-ray spectrometry using the HPGe detector mentioned above. The aliquot of the final product, containing 5–10 MBq of 161Tb, was measured with the HPGe detector until the 3σ uncertainty was below 5%.

Radiochemical purity

The radiochemical purity of the final product was determined by means of radio thin layer chromatography (radio TLC) using a procedure established for 177Lu (Oliveira 2011). The aliquot of 161TbCl3 (2 μL, ~ 100 kBq) was deposited on TLC silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck, Italy) and placed in the chamber with 0.1 M sodium citrate solution (pH 5.5; Merck, Germany) mobile phase. After elution, the plate was dried and analyzed using a radio TLC scanner instrument (Raytest Isotopenmessgeräte GmbH, Germany). The results were interpreted with the MiniGita Control software package (version 1.14, Raytest Isotopenmessgeräte GmbH, Germany).

Radiolabeling yield

Radiolabeling of DOTANOC (ABX GmbH, Germany) at a molar activity of 180 MBq/nmol (1-to-4 nuclide-to-peptide molar ratio) was performed in order to evaluate the success of the purification process. Sodium acetate (Alfa Aesar, Germany; 0.5 M, pH 8) was added to 161TbCl3 solution (~ 200 MBq) to adjust pH to ~ 4.5. The relevant quantity of DOTANOC was subsequently added from a 1 mM stock solution. The reaction solution was incubated for 10 min at 95 °C. The radiolabeling yield was determined by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Merck Hitachi LaChrom) with a radioactivity detector (LB 506, Berthold, Germany) and a C-18 reverse-phase column (150 mm × 4.6 mm; Xterra™ MS, C18; Waters). Trifluoroacetic acid 0.1% (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in MilliQ water (A) and acetonitrile (VWR Chemicals, USA; HPLC grade) (B) were used as mobile phase with a linear gradient of solvent A (95–5% over 15 min) in solvent B at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The sample for the analysis was prepared by diluting ~ 0.3 MBq aliquot of the radiolabeling solution in 100 μL MilliQ water containing sodium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Na-DTPA, 50 μM). The radiolabeling yield of 161Tb-DOTANOC was determined by integration of the product peak from the obtained HPLC chromatogram in relation to the sum of all radioactive peaks (the radiolabeled product, potentially released 161Tb as well as degradation products of unknown structure), which were set to 100%.

Determination of the radiolabeling yield of 161Tb- and 177Lu-DOTA over a two-week period

In order to assess the change of the molar activity of 161Tb-DOTA at different DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios over time (2 weeks after EOS) and to compare it with the molar activity of 177Lu-DOTA, thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was performed. The required DOTA solutions (1–500 pmol DOTA) were obtained by dilution of the initial 1 mM DOTA solution (CheMatech, France) with 0.5 M sodium acetate (pH 4.5). The prepared DOTA dilutions were mixed with 2.5–4 MBq 161Tb (corresponding to 3.1–5 pmol), 177Lu (no-carrier-added, ITG GmbH, Germany) or 177Lu (carrier-added, IDB Holland bv, the Netherlands) at different DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios (160:1 to 1:1). The reaction solutions were incubated for 20 min at 95 °C and 2 μL of each solution were deposited on TLC silica gel 60 F254 plates, which served as a stationary phase. The mixture of 10% ammonium acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and methanol (Merck, Germany) was used as mobile phase (ratio 1:1 (v/v), pH 5.5). After elution, the phosphor screen (Multisensitive, Perkin Elmer Inc., USA) was illuminated with the TLC plate and analyzed with a Cyclon Phosphor Imager (Perkin Elmer Inc., USA). The peaks corresponding to the unlabeled 161Tb or 177Lu (Rf = 0) and to the 161Tb- or 177Lu-DOTA compounds (Rf = 0.4) were integrated with the OptiQuant image analysis software (version 5.0, Perkin Elmer Inc., USA) and the radiolabeling yield determined. Based on the data obtained, the DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios were plotted against the radiolabeling yield using Origin software, fitted with a Boltzmann’s sigmoidal modified equation. Experiments were repeated three times for 161Tb and 177Lu (no-carrier-added) and once for 177Lu (carrier-added). The average DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios, corresponding to 50% labeling efficiency of DOTA with 161Tb (no-carrier-added) and 177Lu (no-carrier-added or carrier-added) at different time points (Day 3 to Day 14 after EOS), were determined and compared with each other for statistical significance by an unpaired t test using Graph Pad Prism (version 7.00).

161Tb/177Lu-DOTATOC stability studies

The radiolabeling of DOTATOC with no-carrier-added 161Tb or no-carrier-added 177Lu at 50 MBq/nmol molar activity (300 MBq 161Tb activity in total) was performed as described above, in the absence or in the presence of L-ascorbic acid (2.9 mg, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The radiolabeling yield was determined by means of HPLC (as described above) immediately after the preparation of 161Tb/177Lu-DOTATOC. The radioactivity concentration of the labeling solutions was adjusted to 250 MBq/500 μL with saline and radiolytic stability of the radioligand was determined over time (1 h, 4 h and 24 h) by means of HPLC.

Results

161Tb production yield (theoretical versus experimental)

No-carrier-added 161Tb was produced by neutron irradiation of enriched 160Gd2O3 (98.2% enrichment) targets via the 160Gd(n,γ)161Gd → 161Tb nuclear reaction. The mass of the target material had to be calculated precisely in order to ensure that the 161Tb activity allowed for international transportation was not exceeded. 161Tb is not explicitly listed in the dangerous goods tables of the ADR (European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road) and International Air Transport Agency (IATA) regulations which are, in turn, based on IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) recommendations. As a result, the generic A2 value (activity limit of radioactive material) according to the “Basic Radionuclide Values for Unknown Radionuclides or Mixtures” of 0.02 TBq has to be applied (IAEA 2012). Due to this restriction, a maximum of 20 GBq 161Tb could be transported internationally (in this case, shipping from ILL and SAFARI-1 research reactors to PSI) (IAEA 2012). Masses of the 160Gd target material, required to produce 20 GBq 161Tb after bombardment at the irradiation facilities, were calculated with the ChainSolver code using the recommended cross-section for thermal neutron capture on 160Gd of 1.4(3) b (Mughabghab 2018). Two-week irradiations at ILL (6.5 mg 160Gd2O3, 1.1015 n.cm− 2.s− 1, 1 day cooling) and at SAFARI-1 (32 mg 160Gd2O3, 2.1014 n.cm− 2.s− 1, 1 day cooling) would theoretically result in 20 GBq 161Tb. At PSI’s neutron source facility (SINQ, 4·1013 n.cm− 2.s− 1) each irradiation cycle is 3 weeks, which was calculated to provide 17.2 GBq 161Tb after the bombardment of 100 mg 160Gd(NO3)3. The masses of the target material could be adapted to operator/user requirements based on the ChainSolver code calculations and neutron fluxes, calculated from the measured 60Co activity values of the 59Co monitors (Table 1). Three ampoules with 59Co were bombarded at the SAFARI-1 nuclear reactor and one ampoule each at ILL and at SINQ irradiation facilities (together with the 160Gd ampoules), respectively. The measured values of the perturbed neutron fluxes in the samples irradiated at the ILL and SAFARI-1 nuclear reactors scaled as expected with the unperturbed neutron flux values reported by the facility in question.

In practice, one-to-two-week irradiations of 160Gd target ampoules using SAFARI-1 (22–33 mg 160Gd2O3) and ILL (7–13 mg 160Gd2O3) research reactors resulted in production of 10–20 GBq of 161Tb (Table 2). The calculated neutron flux at the PNA irradiation position of the SINQ facility was determined experimentally to be only ~ 50% of its originally reported value of 4 1013 n.cm− 2.s− 1 (Table 1), which resulted in 6–9 GBq 161Tb after 3 weeks irradiation of the enriched 160Gd(NO3)3 target material (Table 2). This was due to the fact that the spallation target had recently been replaced and was being operated at a lower beam current (1.3 mA protons instead of 2.3 mA) than normally specified (Table 1).

Table 2.

Production yields of several 161Tb batches, obtained from the irradiation facilities

| Facility | Irradiation time, d | Target material | Mass of the target material, mg | Measured 161Tb activity (EOB), GBq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILL | 5 | 160Gd2O3 | 12.5 | 11.6 |

| ILL | 10 | 160Gd2O3 | 7.3 | 16.7 |

| SAFARI-1 | 14 | 160Gd2O3 | 33.3 | 19.6 |

| SAFARI-1 | 7 | 160Gd2O3 | 32.5 | 11.9 |

| SINQ | 21 | 160Gd(NO3)3 | 94.9 | 8.8 |

| SINQ | 21 | 160Gd(NO3)3 | 86.4 | 6.0 |

Radiochemical separation of 161Tb from the target material and accumulated impurities

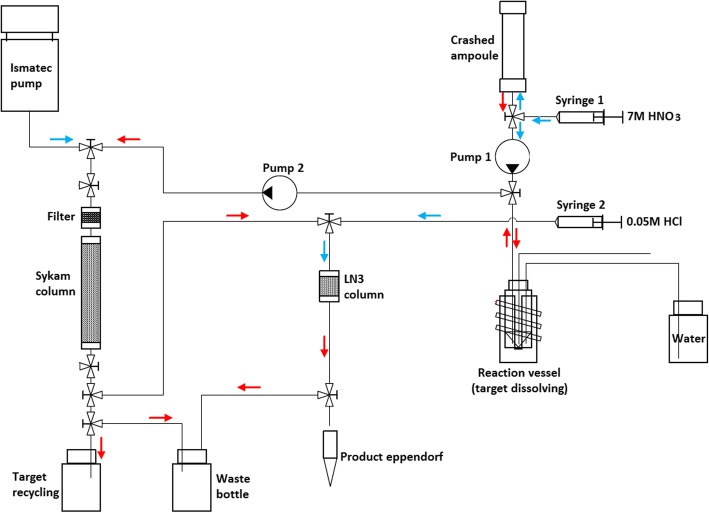

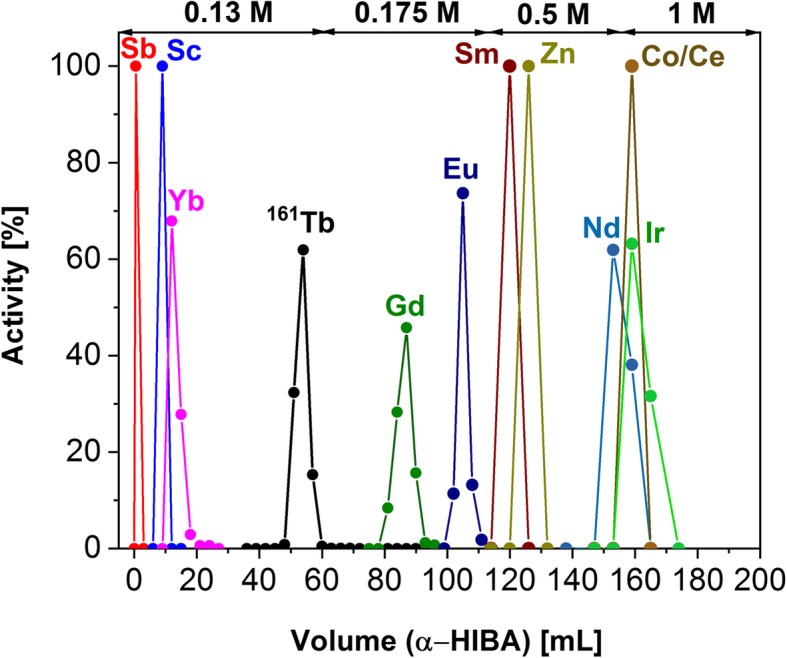

By performing bench experiments using Sykam cation exchange resin column (10 mm × 170 mm) and long-lived radioactive tracers, conditions for the efficient separation of Tb from up to 140 mg of Gd2O3 and the presence of various impurities were established (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2). Subsequently, the established experimental conditions (Sykam resin; 0.13 M α-HIBA, pH 4.5; 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate) were applied towards the purification of the reactor-produced 161Tb (230 MBq). During the irradiation, radioactive side products were co-produced from the impurities of the target material (46Sc, 124Sb, 141Ce, 147Nd, 153Gd, 153Sm, 152/154/155/156Eu, 169Yb) and the ampoule material (65Zn, 60Co, 192Ir). Despite this impurity formation, the established method demonstrated effective 161Tb separation from Gd target material and the impurities using the Sykam resin column (Fig. 1). 161Tb was eluted from the Sykam resin with 20 mL α-HIBA, followed by the concentration of the radionuclide on the LN3 resin column (Additional file 1: Figure S3). LN3 extraction resin was reported to have low affinity for Tb ions in low concentrated acids (McAlister 2007), thereby, allowing 161Tb to be eluted in a small volume of 0.05 M HCl.

Fig. 1.

Elution profile of 161Tb separation from the irradiated target material and side products (10 mm × 170 mm Sykam resin column, 8 mg 160Gd2O3, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate)

Based on the developed two-column purification method (combination of Sykam and LN3 resin columns), a 161Tb purification module was designed (Fig. 2). The module was constructed and placed inside the hot cell, making it possible to perform separations with higher activities (up to 20 GBq) of the reactor-produced 161Tb.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the 161Tb chemical separation system

The established procedure for the 161Tb purification process using the designed module resulted in the elution of the final product (161TbCl3) in a small volume (500 μL) of 0.05 M HCl, with an activity concentration of 11–21 MBq/μL. A separation yield of 80–90% was achieved at EOS. Losses of 10–20% of 161Tb activity were observed in the target dissolving, column loading and final elution steps.

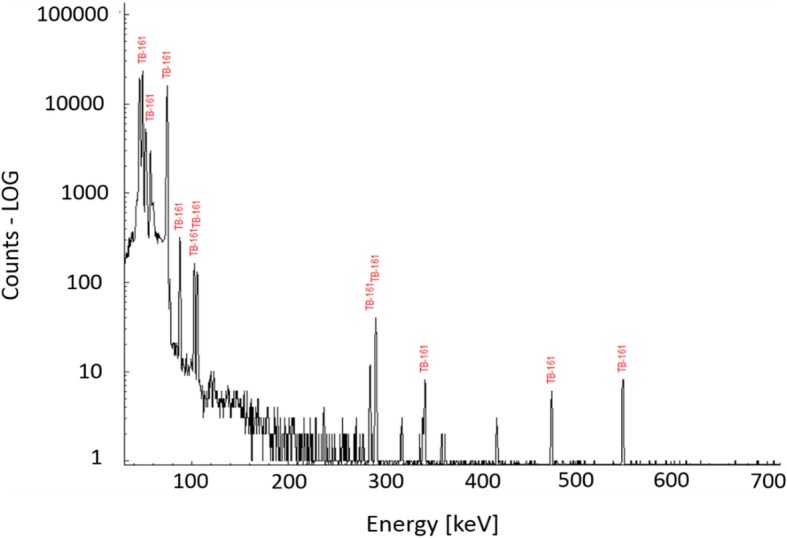

Characteristics of the 161TbCl3 product

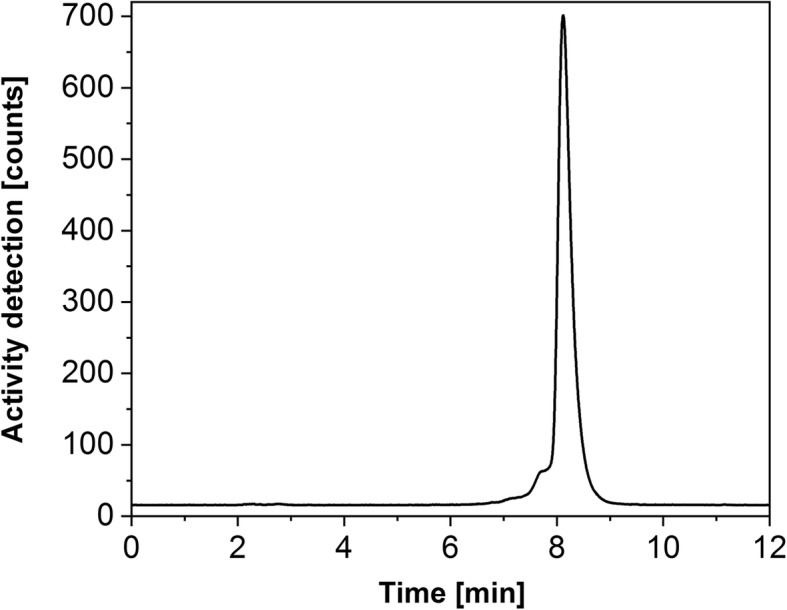

161Tb, obtained after the purification process, was characterized to provide a product specification (Table 3). The identification of the product was confirmed by the 161Tb-characteristic γ-lines (Fig. 3). The content of long-lived 160Tb (T1/2 = 72.3 d), produced by the 159Tb(n,γ)160Tb nuclear reaction due to the presence of 159Tb impurity in the target material (as sold by the vendor), was determined after the decay of 161Tb and did not exceed 0.007% of the total 161Tb activity at EOS (Additional file 1: Figure S4). The radiochemical purity of the 161TbCl3, determined using radio-TLC, was > 99% (Additional file 1: Figure S5). The radiolabeling yield of 161Tb-DOTANOC showed ≥99% efficiency at 180 MBq/nmol molar activity, which corresponds to 1-to-4 nuclide-to-peptide molar ratio (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Product data specification of 161TbCl3, developed in this work, compared to the commercially-available 177LuCl3

| Test | Specification of 161TbCl3 | Specification of 177LuCl3 (EndolucinBeta)a |

|---|---|---|

| Radioactivity concentration | 11–21 MBq/μL | 36–44 MBq/μL |

| Appearance | Clear and colorless solution | Clear and colorless solution |

| pH | 1–2 | 1–2 |

|

Radiolabeling yield HPLC based on radiolabeling with161Tb of DOTANOC, molar ratio 1:4 (180 MBq/nmol) |

> 99% | > 99% |

| Identity 161Tb (γ-ray spectrometry) |

48.9 keV γ-line 74.6 keV γ-line |

113 keV γ-line 208 keV γ-line |

| Radionuclidic purity (γ-ray spectrometry) | 160Tb ≤ 0.007% | 175Yb ≤ 0.01% |

| Radiochemical purity (radio-TLC) | > 99% | > 99% |

aSpecification from the EndolucinBeta certificate of analysis (ITG)

Fig. 3.

Gamma spectrum of 161Tb, obtained after the purification process. The radionuclidic impurity 160Tb is not visible due to the negligible activity as compared to that of 161Tb at end of separation (EOS)

Fig. 4.

HPLC chromatogram of 161Tb-DOTANOC (2.3 min retention time would indicate “free” or unlabeled 161Tb, while 8.2 min indicates 161Tb-DOTANOC)

Comparison of the 161Tb and 177Lu quality, based on the 161Tb- and 177Lu-DOTA molar activities over a two-week period

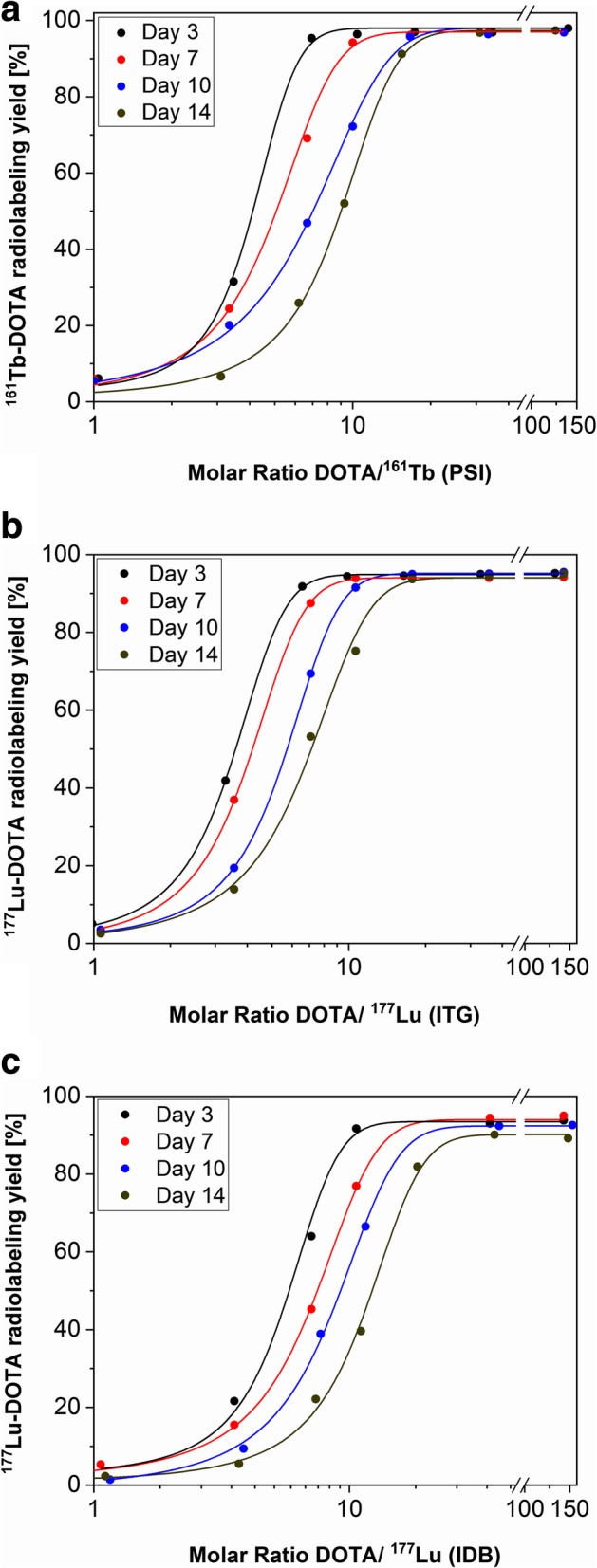

Radiolabeling of DOTA with 161Tb (no-carrier-added) and 177Lu (either carrier-added or no-carrier-added) was performed at different DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios in order to monitor the quality change of the radiolanthanides of interest over a two-week period after EOS. DOTA could be complexed with 161Tb and 177Lu (no-carrier-added) at 15:1 and 13:1 DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios, respectively, with > 90% radiolabeling yield at Day 14 after EOS (Fig. 5 a, b). This indicates the possibility of using the prospective drug product (e.g. DOTA peptides radiolabeled with 161Tb) for up to 2 weeks after the chemical separation. With carrier-added 177Lu, 90% radiolabeling yield was only achieved when using a much higher DOTA-to-nuclide radio (32:1) at the two-week time point (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the radiolabeling yield of (a) no-carrier-added 161Tb (SAFARI-1); b no-carrier-added 177Lu (ITG) and (c) carrier-added 177Lu (IDB) in combination with DOTA over time at different DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios

The average DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios corresponding to 50% labeling efficiency of DOTA with 161Tb and 177Lu were determined at specific time points (Day 3, Day 7, Day 10 and Day 14 – Table 4) (Additional file 1: Figure S7). The values allow an estimation of the possible radiolabeling yield of different biomolecules conjugated with a DOTA chelator, labeled with the radionuclide of interest, over a certain decay period, as well as comparison of the radiolabeling capability of the radionuclides of interest. When DOTA was radiolabeled with carrier-added 177Lu, 50% labeling efficiency was obtained at higher DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios at each time point as compared to no-carrier-added 161Tb and 177Lu, respectively. The 50% labeling efficiency of 161Tb-DOTA was found to be comparable with that of no-carrier-added 177Lu at Day 3 (p = 0.13), while a slight increase of the values was observed for Day 7, Day 10 and Day 14 (p > 0.05), respectively.

Table 4.

DOTA-to-nuclide molar ratios, corresponding to 50% labeling efficiency of 161Tb-DOTA and both carrier-added and no-carrier-added 177Lu-DOTA over a two-week decay period

| Nuclide | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 10 | Day 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 161Tb (PSI) No-carrier-added | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.3 |

| 177Lu (ITG) No-carrier-added | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| 177Lu (IDB) Carrier-added | 5.8* | 7.5* | 9.2* | 12.2* |

* Statistically different to no-carrier-added 161Tb and 177Lu (p < 0.05)

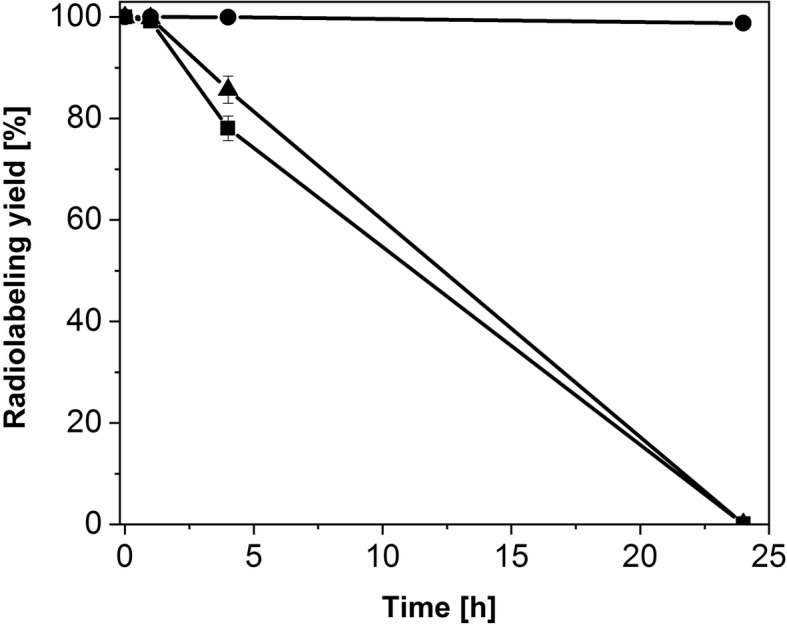

Radiolytic stability of 161Tb-DOTATOC in comparison to 177Lu-DOTATOC

In order to determine whether the conversion and Auger electrons from 161Tb may cause additional radiolytic degradation of radiolabeled somatostatin analogues, stability tests were performed using DOTATOC. The preparation of the any clinically-applied radiopharmaceutical (e.g. 177Lu-DOTATOC, 177Lu-DOTATATE), requires the use of a stabilizer (e.g. L-ascorbic acid, gentisic acid) in order to inhibit peptide autoradiolysis (LUTATHERA n.d.; Mukherjee et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2003; Dash 2015; Esser 2006; Schuchardt 2013). The stability studies of 161Tb-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTATOC were performed with and without addition of L-ascorbic acid. Both 161Tb- and 177Lu-DOTATOC were stable over 24 h incubation in the presence of a stabilizer (L-ascorbic acid) and showed > 98% radiolabeling yield at the 24-h time point. 161Tb-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTATOC were stable over 1 h (> 99% intact product) in the absence of L-ascorbic acid, but both showed radiolytic degradation after an incubation period of 24 h. After 4 h, slight degradation of both 161Tb-DOTATOC (78% intact product) and 177Lu-DOTATOC (85% intact product) was observed (Fig. 6). No significant influence of conversion and Auger electrons from 161Tb on radioligand stability was observed, when compared to 177Lu.

Fig. 6.

Stability of the radiopeptide over time, in the presence and absence of ascorbic acid: the graph shows the % intact 161Tb/177Lu-DOTATOC over a period of 24 h. In the presence of ascorbic acid 177Lu and 161Tb-DOTATOC curves overlap, making it impossible to visualize both simultaneously

Discussion

In the present study, the development of a reproducible chemical separation to produce no-carrier-added 161Tb from enriched 160Gd targets and the characterization of the final product (161TbCl3) is reported. Gd (NO3)3, previously used as target material (Lehenberger 2011), is not suitable for large-scale 161Tb production as lanthanide nitrates are hygroscopic materials, which begin to decompose at 70 °C (Fukuda 2018; Kalekar 2017). The pressure change due to the water evaporation and release of the gases at higher temperatures inside the ampoule may result in the ampoule cracking. The use of oxide targets (melting point 2420 °C) eliminates the potential issues described and will potentially give rise to large-scale 161Tb production in future (TBq activity). The ChainSolver code allows for quick calculations of the required masses of 160Gd targets for the production of the desired 161Tb activity, based on irradiation times and neutron fluxes, obtained with 59Co monitors.

Another big advantage of the newly-devised method over that of the previously-developed one is that the 161Tb product is eluted from LN3 in a small volume and can be used directly for labeling, while the previous method required the use of evaporation after elution from AG50W-X8, thereby, increasing the risk of introduction of environmental contamination and reducing the quality of the final product. The use of LN3 also ensures elution of elements in reverse order when compared to the Sykam/α-HIBA system, therefore, any impurities that may have eluted with 161Tb before introduction to the second column will be eluted differently from the LN3 resin column.

Recently, Brezovcsik et al. reported a Tb separation procedure from massive Gd targets (> 100 mg) using a 20 cm long analytical HPLC column (GE), indicating no mass influence of Gd on the separation process (Brezovcsik 2018). The efficiency of Tb separation from Gd was only 85%, however, showing significant overlapping of Tb and Gd peaks, which would result in the presence of “cold” Gd in the Tb final product and significantly decrease radiolabeling efficiency. The purification method described in this work provides an effective 161Tb separation from the Gd2O3 target material of masses up to 140 mg. This is a valuable result for possible future commercial application of the developed method for 161Tb separation from massive Gd2O3 targets (> 100 mg). For example, 2 weeks irradiation of 160 mg 160Gd2O3 target in ILL's nuclear reactor could theoretically result in the production of 0.5 TBq 161Tb (ChainSolver Code calculations (Romanov 2005)) which can be efficiently purified with the investigated method. 160Gd2O3 target material contains various trace elements (Additional file 1: Table S2), which may show similar chemical behavior to 161Tb on the resin in question and result in the elution of Tb and the impurities in the same fraction. It was demonstrated that, despite the impurities that could be produced via activation of trace elements in the target material or in the quartz ampoule, the established purification method effectively separated the 161Tb from potential impurities present in the system, based on the combination of Sykam and LN3 resin columns.

The two-column 161Tb purification process proposed by Lehenberger et al. (Lehenberger 2011) was adopted as the baseline for this study towards further development. The cation exchange resin of the first column, column dimension and pump flow rate were changed, while the concentration and pH of the eluent remained the same (0.13 M α-HIBA pH 4.5). The resin used for the second column was changed from AG 50 W-X8 (cation exchange resin) to LN3 (extraction resin). These modifications mentioned above played a vital role in obtaining the final product (161TbCl3) in purity comparable to that of the commercially-available no-carrier-added 177LuCl3 (EndolucinBeta). The radiolabeling capability of 161Tb in this work was similar to no-carrier-added 177Lu and three times higher than that of 161Tb obtained by Lehenberger et al. (Lehenberger 2011). Somatostatin analogues could be labeled with no-carrier-added 161Tb (this work) at 1-to-4 nuclide-to-peptide molar ratio (Fig. 4) immediately after the purification process with > 99% radiolabeling yield. Quantitative formation of 161Tb-DOTATATE was possible only at 1-to-12 nuclide-to-peptide molar ratio (Lehenberger 2011).

As expected, the radiolabeling capability of the produced, no-carrier-added 161Tb was higher than the radiolabeling capability of carrier-added 177Lu at each time point over the two-week decay period after the chemical separation process. The faster drop of 161Tb radiolabeling capability as compared to no-carrier-added 177Lu at Day 7, Day 10 and Day 14 after purification (Table 4) could be explained by the lower radioactivity concentration of the final product obtained (11–21 MBq/μL for 161TbCl3 vs 36–44 MBq/μL for 177LuCl3). This implies that the mass ratio between 161Tb and the impurities (Zn, Fe, Co, Pb etc.), which can be introduced during product analysis and post-processing, is lower compared to 177Lu. This results in the potentially stronger interference from environmental impurities during radiolabeling of DOTA with 161Tb than with 177Lu (Asti 2012). Nevertheless, complexation of 161Tb with DOTA was possible at Day 14 (after radiochemical separation) at 1-to-15 nuclide-to-peptide molar ratio (corresponding to 48 MBq/nmol molar activity), with > 90% radiolabeling yield (Fig. 5). This ratio would be appropriate when using DOTA-functionalized targeting agents, such as peptides for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (Dash 2015). These excellent achievements indicate the possible clinical use of 161TbCl3 for a period of up to 2 weeks after EOS. Moreover, clinically-applied DOTATOC radiolabeled with 161Tb was stable over 24 h at high radioactivity concentration, indicating that conversion and Auger electrons had no negative influence on the stability, hence, storage and transportation of 161Tb-labeled somatostatin analogues would be feasible, as is the case for their 177Lu-labeled counterparts.

Conclusions

A new method to separate 161Tb from its enriched 160Gd2O3 target material and co-produced impurities was developed with the use of cation exchange and extraction chromatography, respectively. The method resulted in radionuclidically and radiochemically pure product (161TbCl3), comparable to commercially available, no-carrier-added 177Lu. The quantity and quality of 161Tb is suitable for high-specific radiolabeling, potentially useful for the GMP production of radioligands towards future clinical application.

Additional file

Table S1. Chemical admixtures of 160Gd2O3, provided by the supplier (Isoflex, USA). Table S2. Long-lived radioactive tracers used for bench experiments. Figure S1. Elution profile of Tb/Gd separation from the target material (10 mm x 170 mm Sykam resin column, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate). Experiment 1 (a) was run without addition of natGd2O3, while Experiment 2 (b) was performed with the addition of 140 mg natGd2O3. Figure S2. Elution profile of Tb separation from the target material (Gd) and the impurities of the target material (10 mm x 170 mm Sykam resin column, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate). Experiment 3 (a) 65Zn and 22Na were added to the system as impurities. Experiment 4 (b) 59Fe, 51Cr and 65Ni were added to the system as impurities. Figure S3. Elution profile of Tb separation from Cr as a possible radioactive impurity in the final 161Tb product (6 mm x 5mm LN3 resin column, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate). Figure S4. Gamma spectrum of the decayed product (161TbCl3) used for the determination of 160Tb radionuclidic impurity in the total 161Tb fraction. No other radionuclides, other than 160Tb were found. Figure S5. Radio TLC chromatogram of 161TbCl3 solution in 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.5) for the determination of 161Tb radiochemical purity. (DOCX 911 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank PSI’s Radionuclide - Production and Maintenance Group (Walter Hirzel, Muhamet Djelili, and Alexander Sommerhalder), Roger Hasler, Jiri Ulrich, Dr. Francesca Borgna, Fan Sozzi-Guo, Christoph Umbricht, Alain Blanc and Tobias Schneider for technical support and assistance.

Abbreviations

- EOI

End of Irradiation

- EOS

End of Separation

- GMP

Good Manufacturing Practice

- HPGe

High-purity Germanium

- HPLC

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- IATA

International Air Transport Agency

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- SPECT

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- TLC

Thin Layer Chromatography

- α-HIBA

α-hydroxy-isobutyric acid

Authors’ contributions

NG developed the production and separation process, performed the separation experiments of 161Tb, did the radiolabeling and the stability experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. CM was responsible for the quality assessment of the final product and reviewed/revised the manuscript. ZT and SH supported the chemical separation process and reviewed the manuscript. UK and JRZ were responsible for the irradiation of 160Gd targets at ILL and Necsa, respectively. AV was responsible for the irradiation of 160Gd targets at PSI, as well as the logistics of irradiated ampoules. RS reviewed the manuscript. NvdM was responsible for the development of the production and separation process of 161Tb, organized and supervised the whole study and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (IZLIZ3_156800). The authors acknowledge the Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation for the support of the project through receiving the Petersen Investigator Award 2018.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is (are) included within the article (and its additional file(s)).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nadezda Gracheva, Email: nadezda.gracheva@psi.ch.

Cristina Müller, Email: cristina.mueller@psi.ch.

Zeynep Talip, Email: zeynep.talip@psi.ch.

Stephan Heinitz, Email: stephan.heinitz@sckcen.be.

Ulli Köster, Email: koester@ill.fr.

Jan Rijn Zeevaart, Email: janrijn.zeevaart@necsa.co.za.

Alexander Vögele, Email: alexander.voegele@psi.ch.

Roger Schibli, Email: roger.schibli@psi.ch.

Nicholas P. van der Meulen, Phone: +41-56-310 50 87, Email: nick.vandermeulen@psi.ch

References

- Asti M. Influence of cations on the complexation yield of DOTATATE with yttrium and lutetium: a perspective study for enhancing the 90Y and 177Lu labeling conditions. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezovcsik K. Separation of radioactive terbium from massive Gd targets for medical use. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2018;316:775–780. doi: 10.1007/s10967-018-5718-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Champion C. Comparison between three promising ss-emitting radionuclides, 67Cu, 47Sc and 161Tb, with emphasis on doses delivered to minimal residual disease. Theranostics. 2016;6:1611–1618. doi: 10.7150/thno.15132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHMP . Assessment report EndolucinBeta. 2016. pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dash A. Production of 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy: available options. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;49:85–107. doi: 10.1007/s13139-014-0315-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckerman K. Nuclear decay data for Dosimetric calculations. ICRP Publication 107. Ann ICRP. 2008;38:7–96. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser J. Comparison of [177Lu-DOTA(0),Tyr(3)]octreotate and [177Lu-DOTA(0),Tyr(3)]octreotide: which peptide is preferable for PRRT? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1346–1351. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T. Non-isothermal kinetics of the thermal decomposition of gadolinium nitrate. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2018;55:1193–1197. doi: 10.1080/00223131.2018.1485518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grünberg J. Anti-L1CAM radioimmunotherapy is more effective with the radiolanthanide Terbium-161 compared to Lutetium-177 in an ovarian cancer model. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1907–1915. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2798-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindie E. Dose deposits from 90Y, 177Lu, 111In, and 161Tb in micrometastases of various sizes: implications for radiopharmaceutical therapy. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:759–764. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.170423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IAEA regulations for the safe transport of radioactive material 2012 Edition:46;https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/Pub1570_web.pdf:46.

- Kalekar B. Solid state interaction studies on binary nitrate mixtures of uranyl nitrate hexahydrate and lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate at elevated temperatures. J Nucl Mater. 2017;484:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2016.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kam BL. Lutetium-labelled peptides for therapy of neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39(Suppl 1):103–112. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-2039-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwekkeboom DJ. Radiolabeled somatostatin analog [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3] octreotate in patients with endocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2754–2762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehenberger S. The low-energy β− and electron emitter 161Tb as an alternative to 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Ellars CE, Edwards DS. Ascorbic acid: useful as a buffer agent and radiolytic stabilizer for metalloradiopharmaceuticals. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:1052–1056. doi: 10.1021/bc034109i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://ndclist.com/ndc/69488-003. LUTATHERA.

- Marin I. Establishment of optimized SPECT/CT protocol for therapy with 161Tb demonstrate improved image quality with Monte Carlo based OSEM reconstruction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(Suppl 1):S16. [Google Scholar]

- McAlister D. Characterization of extraction of chromatographic materials containing Bis (2-ethyl-1-hexyl) phosphoric acid, 2-Ethyl-1-hexyl (2-Ethyl-1-hexyl) Phosphonic acid, and Bis(2,4,4-Trimethyl-1-Pentyl) Phosphinic acid. Solvent Extr Ion Exch. 2007;25:757–769. doi: 10.1080/07366290701634594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Lohar S, Dash A, Sarma HD, Samuel G, Korde A. Single vial kit formulation of DOTATATE for preparation of 177Lu-labeled therapeutic radiopharmaceutical at hospital radiopharmacy. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2015;58:166–172. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. A unique matched quadruplet of terbium radioisotopes or PET and SPECT and for α- and β−-radionuclide therapy: an in vivo proof-of-concept study with a new receptor-targeted folate derivative. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1951–1959. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. Direct in vitro and in vivo comparison of 161Tb and 177Lu using a tumour-targeting folate conjugate. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:476–485. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2563-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. Terbium-161 for PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate Cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(Suppl 1):53–54. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04345-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. Scandium and terbium radionuclides for radiotheranostics: current state of development towards clinical application. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20180074. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira ID. Alternative methods for radiochemical purity tesing in radiopharmaceuticals. Belo Horizonte: International Nuclear Atlantic Conference - INAC 2011; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mughabghab, S. Recommended thermal cross sections, resonance properties, and resonance parameters for Z = 61–102. Atlas of neutron resonances (Sixth Edition) 2018, p. 111–679.

- Romanov E. ORIP XXI Computer Programs for Isotope Transmutation Simulations, Proceedings of M&C2005. International Topical Meeting on Mathematics and Computation, Supercomputing, Reactor Physics and Nuclear and Biological Applications (Avignon, France) on CDROM. 2005. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Sansovini M. Treatment with the radiolabelled somatostatin analog 177Lu-DOTATATE for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;97:347–354. doi: 10.1159/000348394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchardt C. Dosimetry in targeted radionuclide therapy: the Bad Berka dose protocol - practical experience. J Postgrad Med Edu Res. 2013;47:65–73. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10028-1058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solá G. Lutetium-177-EDTMP for bone pain palliation. Preparation, biodistribution and pre-clinical studies. Radiochim Acta. 2000;88:157–161. doi: 10.1524/ract.2000.88.3-4.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg J. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:125–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Essen M. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-octreotate in patients with foregut carcinoid tumours of bronchial, gastric and thymic origin. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1219–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Chemical admixtures of 160Gd2O3, provided by the supplier (Isoflex, USA). Table S2. Long-lived radioactive tracers used for bench experiments. Figure S1. Elution profile of Tb/Gd separation from the target material (10 mm x 170 mm Sykam resin column, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate). Experiment 1 (a) was run without addition of natGd2O3, while Experiment 2 (b) was performed with the addition of 140 mg natGd2O3. Figure S2. Elution profile of Tb separation from the target material (Gd) and the impurities of the target material (10 mm x 170 mm Sykam resin column, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate). Experiment 3 (a) 65Zn and 22Na were added to the system as impurities. Experiment 4 (b) 59Fe, 51Cr and 65Ni were added to the system as impurities. Figure S3. Elution profile of Tb separation from Cr as a possible radioactive impurity in the final 161Tb product (6 mm x 5mm LN3 resin column, 0.6 mL/min eluent flow rate). Figure S4. Gamma spectrum of the decayed product (161TbCl3) used for the determination of 160Tb radionuclidic impurity in the total 161Tb fraction. No other radionuclides, other than 160Tb were found. Figure S5. Radio TLC chromatogram of 161TbCl3 solution in 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.5) for the determination of 161Tb radiochemical purity. (DOCX 911 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is (are) included within the article (and its additional file(s)).