Abstract

Purpose

To determine the effect of revascularisation for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) on QoL in the first and second year following diagnosis, to compare the effect depicted by Short Form Six Dimensions (SF-6D) and EuroQoL five Dimensions (EQ-5D) utilities, and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores and to analyse heterogeneity in treatment response.

Methods

Longitudinal data from 229 PAD patients were obtained in an observational study in southern Netherlands. Utility scores were calculated with the international (SF-6D) and Dutch (EQ-5D) tariffs. We analysed treatment effect at years 1 and 2 through propensity score-matched ANCOVAs. Thereby, we estimated the marginal means (EMMs) of revascularisation and conservative treatment, and identified covariates of revascularisation effect.

Results

A year after diagnosis, 70 patients had been revascularised; the EMMs of revascularisation were 0.038, 0.077 and 0.019 for SF-6D, EQ-5D and VAS, respectively (always in this order). For conservative treatment these were − 0.017, 0.038 and 0.021. At 2-year follow-up, the EMMs of revascularisation were 0.015, 0.077 and 0.027, for conservative treatment these were − 0.020, 0.013 and − 0.004. Baseline QoL (and rest pain in year 2) were covariates of treatment effect.

Conclusions

We measured positive effects of revascularisation and conservative treatment on QoL a year after diagnosis, the effect of revascularisation was sustained over 2 years. The magnitude of effect varied between the metrics and was largest for the EQ-5D, which may be most suitable for QoL measurement in PAD patients. Baseline QoL influenced revascularisation effect, in clinical practice this may inform expected QoL gain in individual patients.

Keywords: Peripheral arterial disease, Peripheral revascularisation, Utility, EuroQol EQ-5D (EQ-5D), SF-6D

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a chronic disease, characterised by the atherosclerotic narrowing of the lower extremity arteries [1]. PAD prevalence is estimated to be 3–10% overall, and 15–20% in the population older than 70 [2]; these numbers seem to be increasing [3]. The disease spectrum ranges from asymptomatic PAD to limb and life-threatening acute leg ischemia [4]. Symptomatic PAD, characterised by exercise-induced occurrence of ischemic muscle pain, causes loss in quality of life (QoL) through reduced physical well-being, mobility, independence and capacity to handle everyday life [5]. Peripheral revascularisation, the open- or endovascular restoring of blood flow in the legs, (f.i. angioplasty, bypass surgery), is typically applied for acute limb ischemia or disease progression despite conservative treatment [2] to restore peripheral reperfusion and reduce the symptom burden.

Previous studies have shown a positive effect on QoL a year after revascularisation [6]; the long-term effects of revascularisation are less verified as progression of atherosclerosis can cause restenosis [7]. Studies showed that 6 months after revascularisation, mean EuroQoL five Dimensions (EQ-5D) utilities increased, then stagnated during the following year [8]; 4 years after revascularisation, pain was the only Nottingham health profile domain significantly improved [9]. This calls into question the sustainability of the effect of revascularisation on QoL.

Guidelines recommend revascularisation only in selected patients with mild to moderate disease [7]. This indicates that disease severity might be a covariate of revascularisation effect on QoL, and some patients might achieve more desirable results than others. This hypothesis is supported by studies showing that 1 year after revascularisation, a proportion of patients did not achieve the desired results: 24.4%, 30.8% and 21.0% of patients did not have improved SF-36 domain scores for physical function, pain or a relevant EQ-5D utility improvement, respectively [10, 11].

In the above-mentioned studies, different methods were used to generate preferences for QoL. The Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) and EQ-5D are based on the valuation of hypothetical health states by members of the general public, i.e. general public preference, in contrast the Nottingham health profile uses the patient’s self-perceived health state preference, i.e. patient preference. It is acknowledged that different methods to generate QoL estimates will measure different aspects of QoL and thus will result in similar but not identical estimates. Research on instruments using general public vs. patient preferences has shown that results can differ, with the general public valuing health worse than patients do [12]. These findings have been confirmed in the valuation of cardiovascular events [13]. All mentioned instruments are generic, i.e. not designed specifically for PAD patients but can be used in any patient population. Differences can also arise between two generic, general public-based instruments [14], and arguments for and against several generic instruments in PAD patients have been presented [15–18]. The review of Poku et al. [18] concludes that the evidence on the psychometric properties of QoL instruments in PAD patients was limited and did not allow for the detection of superiority of one instrument. The evidence focussed on construct validity and responsiveness and reported favourable results for both SF-6D and EQ-5D. The review of Dyer et al. [19] positively commented on the convergent validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in PAD patients but did not assess the SF-6D.

PAD treatment is not curative but targeted at relieving PAD symptoms. Consequently, sustainability of QoL gains after revascularisation and variability in the magnitude of gains by patient characteristics are relevant factors in clinical decision making. Beyond that, however, estimations of treatment effect on QoL directly affect the number of quality-adjusted life years attributable to that intervention, and thus play a key role in the evaluation of cost-effectiveness of PAD treatment. Differences between QoL instruments can influence cost-effectiveness estimates, which can misinform policy decision and eventually can lead to the suboptimal use of healthcare. To address those issues, we (1) evaluated, 1 year after PAD diagnosis, the effect of revascularisation on QoL in terms of magnitude and influence of covariates, and compared these results between three QoL metrics, (2) evaluated, 2 years after PAD diagnosis, the sustainability of the effect of revascularisation in year one on QoL, in terms of magnitude and influence of covariates and compared these results between three QoL metrics. This paper presents estimates of treatment effect and offers recommendations for the choice of QoL metric.

Methods

Study design

This observational study was conducted between January 2009 and November 2013 in three Dutch hospitals. Approval was obtained at the Medical Ethical Committee (CMO) of the MUMC+. Medical history and QoL was documented in consecutive newly diagnosed PAD patients, who were followed up over 2 years with repeated QoL measurements and documentation of peripheral revascularisation interventions.

Study population

Patients referred to the vascular department for newly diagnosed PAD were eligible for participation. Inclusion criterion was an ankle brachial index (ABI; the ratio between systolic blood pressure in ankle and arm, measured at rest [20]) of < 0.9 in any leg, measured in the hospital. Patients were included after signing informed consent. Exclusion criteria are listed in Appendix 2. Furthermore, patients were excluded from the analysis when none of the baseline and follow-up QoL instruments had been returned. To ensure homogeneity of time since revascularisation, patients were excluded when revascularisation took place less than 90 days before year 1 follow-up, this was based on medical expert opinion.

Data collection

For each patient, a case report form was created in an online database, containing patient characteristics, QoL and treatment. Patient characteristics were self-reported in an interview with a research nurse or study physician. At baseline, 1 and 2 years after study inclusion, patients filled in the SF-36 and the EQ-5D measurement instruments. By questionnaire, patients reported treatments received and cardiovascular events experienced during the previous year, 1 and 2 years after baseline (see Appendix 2 for a definition of cardiovascular events); these data were cross-checked with patient medical files for completeness. A research nurse telephoned the patient upon missing data or ambiguous answers.

Patient characteristics and treatment

A summary of patient characteristics tested as covariates of treatment effect, their definitions and specifications used in the analyses is given in Table 1. Patients received conservative treatment according to PAD guidelines [7]. This included lifestyle advice regarding smoking cessation and physical exercise, and pharmacotherapy focussed on controlling blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Patients were advised to do unsupervised exercise or received exercise therapy supervised by a physiotherapist. Invasive treatment was defined as peripheral revascularisation which entailed endovascular interventions (e.g. angioplasty with and without stent placement) and open surgery (e.g. atherectomy and endarterectomy, and bypass surgery). Revascularisations were considered relevant for this study when performed within 1 year of PAD diagnosis.

Table 1.

Names and definitions of patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Definition |

|---|---|

| Disease severity | |

| Fontaine stage |

PAD severity grading system [21] Mild = (I) asymptomatic, (IIa) claudication at > 200 m walking distance Severe = (IIb) claudication at < 200 m walking distance, (III) rest pain and (IV) necrosis or gangrene |

| ABI | Lower ABI (left or right ankle blood pressure/higher brachial blood pressure) [22] |

| Claudication distance | Distance walked in m to provoke claudication symptoms |

| Rest pain | Patient-reported pain at rest |

| Complaints in daily life | Patient-reported complaints during activities of daily life |

| Progressive symptoms | Patient reported, within the past 6 months |

| Demographics | |

| Age | In years |

| Gender | Male or female |

| BMI | Body mass in kg divided by the square of the body height in m [23] |

| Currently smoking | Patient-reported smoking status |

| Comorbidities | |

| Stroke | Diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack > 6 months ago |

| Myocardial infarction | Diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction > 6 months ago |

| DM I | Diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes |

| DM II | Diagnosis of non-insulin-dependent diabetes |

| Hypertension | BP of > 140/90 mmHg and treated with antihypertensive medication |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Treatment with cholesterol-lowering drugs |

| Elevated D-Dimer |

In patients ≤ 50 years old: D-Dimer > 500 µg/L In patients > 50 years: D-Dimer in µg/L > patient’s age * 10 |

| Impaired kidney function |

Indicated by Modification of Diet in Renal Disease estimated glomerular filtration rate (MDRD). Estimated from serum creatinine, age and gender Cut-off: < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [24] |

| Malignancies | Previous or current malignancies |

Short Form 36 Health Survey based SF-6D

The SF-36 is a well-known generic health-related quality-of-life (HR-QoL) metric that has been extensively tested in Dutch populations [25]. The SF-6D has been developed to estimate HR-QoL using ten of the thirty-six items of the SF-36 [26]. Four to six ordinal answers are offered per item, each answer matched with a preference weight to value the desirability of the answer. In the absence of a Dutch tariff, the UK tariff of the SF-6D was used. Combining the valued item responses, domain scores and an overall utility are calculated, each of them between 0.29 and 1.00 to indicate maximum disability to perfect health [25].

EuroQoL five dimensions

The EQ-5D is a generic QoL instrument. Since 2008, the 3-level version of the EQ-5D used in this study is the preferred QoL measure in economic evaluations conducted for NICE in the United Kingdom [27]. In the Netherlands, this recommendation has been superseded in favour of the newer 5-level version of the EQ-5D in 2016 [28].The instrument consists of two metrics, the first being a self-classification of health in five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The respondent indicates if ‘no problems’, ‘some problems’ or ‘severe problems’ occur in each domain; the Dutch tariff of Lamers et al. [29] is used to value the response with a preference weight. All domains combined, a utility is created; the maximum utility of one indicates perfect health, a utility of zero indicates death and the minimum utility of -0.33 indicates conditions worse than death [30].

The second metric, the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) is a psychometric response scale, recording the respondent’s valuation of their overall health on a scale from 100 to 0, representing best imaginable to poorest imaginable health [30]. The VAS represents a patient’s preference for her own health state. For comparability purposes, VAS scores were divided by 100 to create a score between 1 and 0.

Missing data

To prevent a loss of precision and the introduction of bias through the exclusion of patients with missing data, missing items of the quality-of-life instruments and baseline patient characteristics were replaced using multiple imputation [31]. Categorical items of the QoL instruments were imputed using dummy coding [32]. We set the number of imputations to 10 and performed sensitivity analysis comparing outcomes of the pooled imputed datasets to a complete case analysis (see Appendixes 1 and 4). Patients who died received a score of 0 in all following QoL measurements.

Propensity score matching

For each of the 10 imputed datasets, a propensity score (PS) was estimated using logistic regression of baseline patient data [33]. The propensity score was created by testing all baseline patient characteristic parameters for their ability to predict treatment assignment, selecting those parameters with the highest C-statistics and adding parameters that remained unbalanced until the propensity score resulted in adequate covariate balance of baseline characteristics. On this score, each revascularised patient was matched (with replacement) with one conservatively treated patent using the nearest neighbour technique and a calliper of 0.2 [34]. Covariate balance after matching was assessed by comparison of patient characteristics in the treatment groups and by means of visual inspection of QQ plots and PS distributions in the original and matched groups [34]. PS-matched datasets are adjusted against confounding by indication of treatment, allowing outcomes of treatment groups to be compared. PS matching was performed in R version 3.3.3.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of patients with complete and incomplete QoL measurements were compared using Bonferroni corrected t tests and Chi-square tests [35]. Paired-samples t test were used to compare baseline QoL scores of the three instruments. Scatterplots and Pearson correlations were used to explore the effect of time since revascularisation on QoL change at year 1 follow-up.

To explore covariates of treatment effect and compare QoL response in revascularised and conservatively treated patients, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used in the matched cohort producing estimated marginal means (EMMs) of revascularisation and conservative treatment in a post hoc analysis. Patient characteristics described in Table 1 and their interaction terms with revascularisation were included into the models. A backwards deletion approach with the P value set to 0.05 was used; all variables were tested for multi-collinearity, variables were excluded if variance inflation factor (VIF) > 1/(1–model R2) [36]. Variables found significant in one of the three QoL metric’s models were entered into the models of all metrics. The analysis was conducted on baseline to year 1 change and baseline to year 2 change, and the latter analysis excluded patients with revascularisations in the second year. Analysis results that could not be pooled across multiple imputation datasets were presented as ranges. Sensitivity analyses were performed by comparing EMMs to crude scores and by applying the ANCOVA models in:

the unmatched sample;

the unmatched sample, exclusively using patients without cardiovascular events during follow-up;

the unmatched sample, exclusively using complete cases;

a sample excluding patients revascularised in the second half of the first follow-up year.

All statistical analyses were conducted on SF-6D, EQ-5D and VAS for comparison, using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.

Results

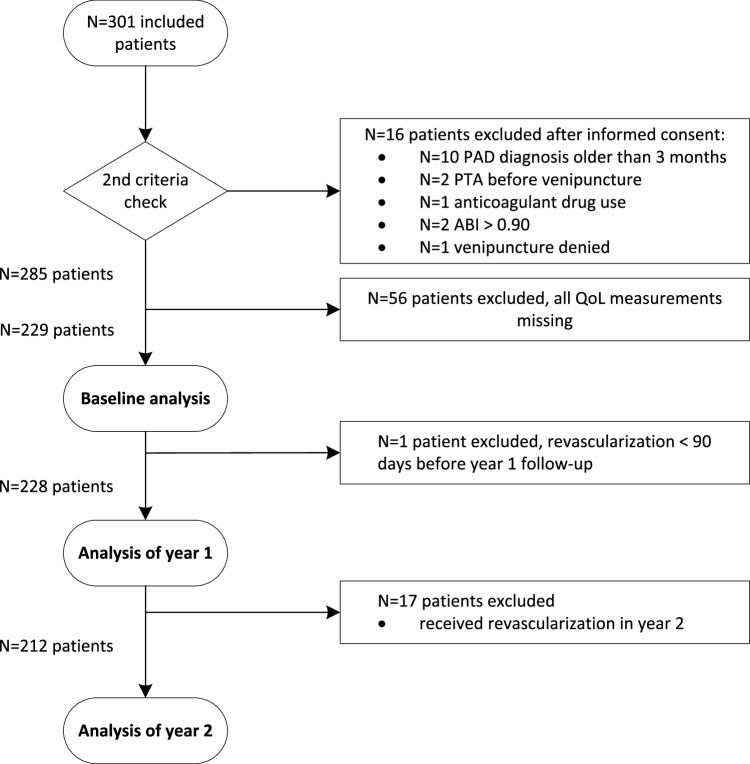

The study population consisted of 285 patients. After exclusion of 56 patients for completely missing QoL measurements, the population analysed consisted of 229 PAD patients (see Fig. 1 for patient flow). Between 16.6 and 42.4% of metrics were missing, the measurement time with the largest proportions of missing values was 1-year follow-up and the metric with the largest proportions of missingness was SF-6D (see Table 5 in Appendix 1). Patients with and without missing QoL scores showed few differences in baseline characteristics (see Table 6 in Appendix 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow

Table 5.

Available and missing data, scores at floor and ceiling

| Baseline | 1-Year follow-up | 2-Year follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 229 | 225 | 218 |

| At least one QoL score available | 91.3% | 66.8% | 69.4% |

| SF-6D missing | 28.4% | 41.5% | 42.4% |

| EQ-5D missing | 16.6% | 35.4% | 33.6% |

| VAS missing | 17.5% | 35.8% | 34.1% |

Table 6.

Characteristics of patients with and without missing QoL measurements

| Characteristic | Baseline | Year 1 | Year 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete cohort (229) | Rev. (70) | Cons. (159) | All instruments completed (142) | One or more missing (87) | All instruments completed (127) | One or more missing (98) | All instruments completed (127) | One or more missing (91) | |

| SF-6D (mean (SE)) | 0.689 (0.009) | 0.651 (0.015) | 0.706 (0.010) | 0.710 (0.011) | 0.655 (0.015) | 0.748 (0.011) | 0.654 (0.013) | 0.746 (0.012) | 0.657 (0.013) |

| EQ-5D (mean (SE)) | 0.637 (0.019) | 0.571 (0.036) | 0.666 (0.020) | 0.664 (0.020) | 0.594 (0.037) | 0.729 (0.018) | 0.623 (0.028) | 0.738 (0.019) | 0.667 (0.028) |

| VAS (mean (SE)) | 0.665 (0.015) | 0.629 (0.029) | 0.681 (0.018) | 0.684 (0.013) | 0.633 (0.032) | 0.711 (0.016) | 0.654 (0.040) | 0.712 (0.016) | 0.675 (0.039) |

| Age (mean) | 65.8 | 64.0 | 66.5 | 65.3 | 66.5 | 66.0 | 65.7 | 64.9 | 66.8 |

| Men (%) | 64.6 | 67.1 | 63.5 | 68.3 | 58.6 | 69.3 | 57.1 | 72.4 | 54.9 |

| ABI (mean) | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.76 |

| Current smoker (%) | 53.3 | 58.6 | 50.9 | 55.6 | 49.4 | 54.3 | 53.1 | 58.3 | 47.1 |

| Severe Fontaine stage (%) | 36.7 | 51.4 | 30.2 | 32.4 | 43.7 | 31.5 | 43.9 | 29.9 | 45.1 |

| Progressive symptoms (%) | 50.7 | 74.3 | 40.3 | 51.4 | 49.4 | 48.8 | 52.0 | 48.8 | 52.9 |

| Hypertension (%) | 54.1 | 51.4 | 53.5 | 53.5 | 51.7 | 52.0 | 57.1 | 50.4 | 55.9 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 49.8 | 45.7 | 51.6 | 46.5 | 55.2 | 52.0 | 48.0 | 52.0 | 47.1 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17.0 | 15.7 | 17.6 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 18.6 |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 12.2 | 7.1 | 14.5 | 11.3 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 16.3 | 10.2 | 14.7 |

| Stroke (%) | 12.7 | 17.1 | 10.7 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 11.2 | 12.7 | 11.8 |

Significantly different utilities marked bold

Rev revascularisation procedure, including endovascular interventions, e.g. angioplasty with and without stent placement, and open surgery, e.g. atherectomy and endarterectomy, and bypass surgery, Cons conservative treatment, SE standard error

Population characteristics

Mean age at baseline was 66 years (SD 8.141), the cohort consisted of 64.6% males and 53.3% current smokers. Mean resting ABI was 0.72 (SD 0.188), the prevalence rates of Fontaine stages IIb, III and IV were 33.6%, 2.2% and 0.9%, respectively (see Table 2 for more baseline patient characteristics). Mean baseline QoL was 0.689 (SE 0.009) measured by the SF-6D, 0.637 (SE 0.019) measured by the EQ-5D and 0.665 (SE 0.015) measured by the VAS. SF-6D and EQ-5D QoL were significantly different from one another, for further details on baseline QoL, see Tables 6 and 7, Figs. 2a and 5 in Appendix 1. At 1-year follow-up, 70 patients (30.6%) had received revascularisation, and no relationship was detected between time since revascularisation and change in QoL at year 1. Eighteen patients (7.9%) experienced a cardiovascular event in the first year and seventeen patients during the second year (7.4%). Seventeen patients were revascularised in the second year (7.4%).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics, frequencies and missingness

| Characteristic | Na (%) | Missing values (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Male gender | 148 (64.6) | 0 (0) |

| Currently smoking | 122 (53.3) | 1 (1) |

| Age ± SD | 65.8 ± 8.1 | 0 (0) |

| Body mass index ± SD | 26.6 ± 4.1 | 31 (13) |

| Disease severity | ||

| Fontaine I | 9 (3.9) | 1 (1) |

| Fontaine IIa | 136 (59.4) | |

| Fontaine IIb | 77 (33.6) | |

| Fontaine III | 5 (2.2) | |

| Fontaine IV | 2 (0.9) | |

| Progressive symptoms | 116 (50.7) | 0 (0) |

| Rest pain | 40 (17.5) | 2 (1) |

| Complaints in daily life | 128 (55.9) | 5 (2) |

| Claudication distance < 100 m | 61 (26.6) | 4 (2) |

| Ankle-brachial-index ± SD | 0.72 ± 0.19 | 0 (0) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Stroke | 29 (12.7) | 0 (0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 28 (12.2) | 0 (0) |

| No diabetes | 190 (83.0) | 0 (0) |

| Untreated diabetes | 5 (2.2) | |

| Diabetes mellitus II | 27 (11.8) | |

| Diabetes mellitus I | 7 (3.1) | |

| Hypertension | 121 (54.1) | 0 (0) |

| Cholesterol-lowering drug use | 188 (82.1) | 0 (0) |

| Elevated D-Dimer | 72 (31.4) | 6 (3) |

| Impaired kidney function | 48 (21.0) | 30 (13) |

| Malignancies | 21 (9.2) | 0 (0) |

SD standard deviation

aPatient characteristics after imputation of missing values

Table 7.

Baseline heterogeneity in quality of life

| Characteristic | SF-6D | EQ-5D | VAS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SE) | Mediana | Mean | (SE) | Mediana | Mean | (SE) | Mediana | |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Male gender | 0.692 | 0.011 | 0.696 | 0.632 | 0.022 | 0.691 | 0.663 | 0.022 | 0.700 |

| Female gender | 0.684 | 0.014 | 0.673 | 0.647 | 0.030 | 0.691 | 0.668 | 0.024 | 0.700 |

| Currently smoking | 0.671 | 0.012 | 0.666 | 0.619 | 0.024 | 0.691 | 0.650 | 0.022 | 0.700 |

| Currently not smoking | 0.710 | 0.013 | 0.704 | 0.658 | 0.027 | 0.726 | 0.682 | 0.026 | 0.700 |

| Age > 75 | 0.672 | 0.024 | 0.683 | 0.633 | 0.053 | 0.691 | 0.651 | 0.048 | 0.700 |

| Age < 75 | 0.692 | 0.010 | 0.696 | 0.638 | 0.020 | 0.691 | 0.667 | 0.019 | 0.700 |

| Body mass index > 30 | 0.657 | 0.018 | 0.642 | 0.596 | 0.047 | 0.691 | 0.626 | 0.037 | 0.640 |

| Body mass index < 30 | 0.696 | 0.010 | 0.696 | 0.647 | 0.019 | 0.691 | 0.674 | 0.016 | 0.700 |

| Disease severity | |||||||||

| Fontaine mild | 0.704 | 0.011 | 0.700 | 0.670 | 0.020 | 0.691 | 0.679 | 0.019 | 0.700 |

| Fontaine severe | 0.664 | 0.015 | 0.645 | 0.581 | 0.033 | 0.691 | 0.641 | 0.027 | 0.700 |

| Progressive symptoms | 0.662 | 0.013 | 0.649 | 0.587 | 0.026 | 0.691 | 0.639 | 0.020 | 0.700 |

| Non-progressive symptoms | 0.717 | 0.012 | 0.728 | 0.689 | 0.023 | 0.691 | 0.692 | 0.021 | 0.700 |

| Rest pain | 0.626 | 0.017 | 0.614 | 0.558 | 0.039 | 0.620 | 0.587 | 0.035 | 0.600 |

| No Rest pain | 0.703 | 0.010 | 0.699 | 0.654 | 0.022 | 0.691 | 0.681 | 0.016 | 0.700 |

| Complaints in daily life | 0.646 | 0.011 | 0.630 | 0.578 | 0.025 | 0.691 | 0.626 | 0.020 | 0.650 |

| No complaints in daily life | 0.744 | 0.012 | 0.753 | 0.713 | 0.022 | 0.727 | 0.715 | 0.024 | 0.750 |

| Claudication < 100 m walking | 0.664 | 0.018 | 0.646 | 0.548 | 0.037 | 0.691 | 0.608 | 0.031 | 0.640 |

| Claudication > 100 m walking | 0.698 | 0.010 | 0.696 | 0.670 | 0.021 | 0.691 | 0.686 | 0.018 | 0.700 |

| Ankle-brachial-index < 0.5 | 0.703 | 0.028 | 0.753 | 0.622 | 0.056 | 0.691 | 0.688 | 0.049 | 0.700 |

| Ankle-brachial-index > 0.9 | 0.688 | 0.010 | 0.675 | 0.639 | 0.019 | 0.691 | 0.662 | 0.016 | 0.700 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Stroke | 0.661 | 0.024 | 0.648 | 0.557 | 0.053 | 0.691 | 0.622 | 0.046 | 0.600 |

| No stroke | 0.693 | 0.010 | 0.677 | 0.649 | 0.020 | 0.691 | 0.671 | 0.015 | 0.700 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.701 | 0.023 | 0.698 | 0.661 | 0.049 | 0.691 | 0.677 | 0.061 | 0.700 |

| No myocardial infarction | 0.688 | 0.010 | 0.675 | 0.634 | 0.020 | 0.691 | 0.663 | 0.015 | 0.700 |

| Diabetes | 0.674 | 0.020 | 0.669 | 0.631 | 0.044 | 0.691 | 0.628 | 0.037 | 0.675 |

| No diabetes | 0.692 | 0.010 | 0.677 | 0.639 | 0.021 | 0.691 | 0.673 | 0.016 | 0.700 |

| Hypertension | 0.688 | 0.012 | 0.640 | 0.640 | 0.022 | 0.691 | 0.656 | 0.021 | 0.700 |

| No hypertension | 0.691 | 0.013 | 0.635 | 0.635 | 0.029 | 0.691 | 0.674 | 0.022 | 0.700 |

| Cholesterol-lowering drug use | 0.693 | 0.010 | 0.691 | 0.635 | 0.022 | 0.691 | 0.664 | 0.017 | 0.700 |

| No Cholesterol-lowering drug use | 0.671 | 0.020 | 0.637 | 0.649 | 0.032 | 0.691 | 0.669 | 0.034 | 0.700 |

| Elevated D-Dimerb | 0.670 | 0.015 | 0.671 | 0.615 | 0.030 | 0.691 | 0.649 | 0.028 | 0.700 |

| Normal D-Dimer | 0.698 | 0.011 | 0.694 | 0.648 | 0.023 | 0.691 | 0.672 | 0.018 | 0.700 |

| Impaired kidney functionc | 0.705 | 0.017 | 0.698 | 0.699 | 0.030 | 0.727 | 0.679 | 0.039 | 0.720 |

| Normal kidney function | 0.685 | 0.010 | 0.673 | 0.621 | 0.022 | 0.691 | 0.661 | 0.017 | 0.700 |

| Malignancies | 0.730 | 0.025 | 0.753 | 0.699 | 0.052 | 0.727 | 0.665 | 0.068 | 0.700 |

| No malignancies | 0.685 | 0.009 | 0.675 | 0.631 | 0.019 | 0.691 | 0.665 | 0.016 | 0.700 |

SE standard error

aMedian of all 10 imputed datasets combined

bElevated D-Dimer is defined as D-Dimer > 500 when age < 50, as D-Dimer > age * 10 when age > 50

cImpaired kidney function is defined as MDRD eGFR below 60

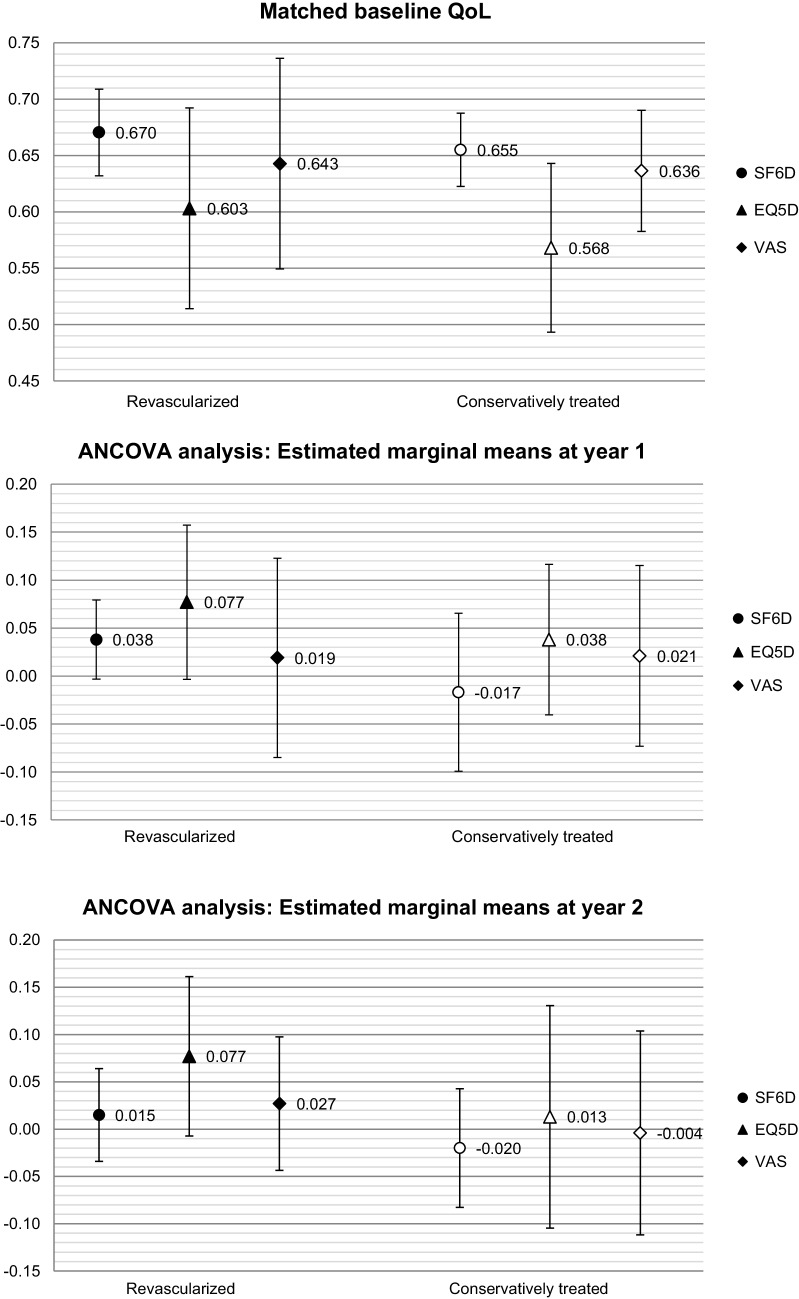

Fig. 2.

a–c Matched baseline scores, EMMs of year 1 and EMMs of year 2

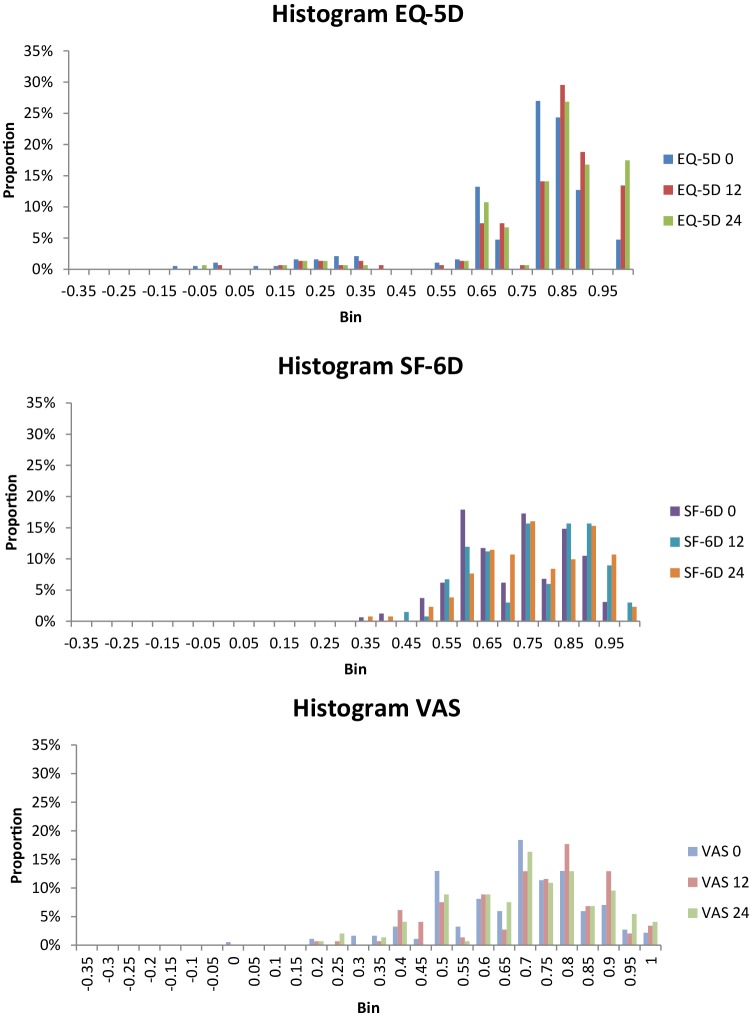

Fig. 5.

Floor and ceiling effects

Revascularisation effect and heterogeneity in response during the first year

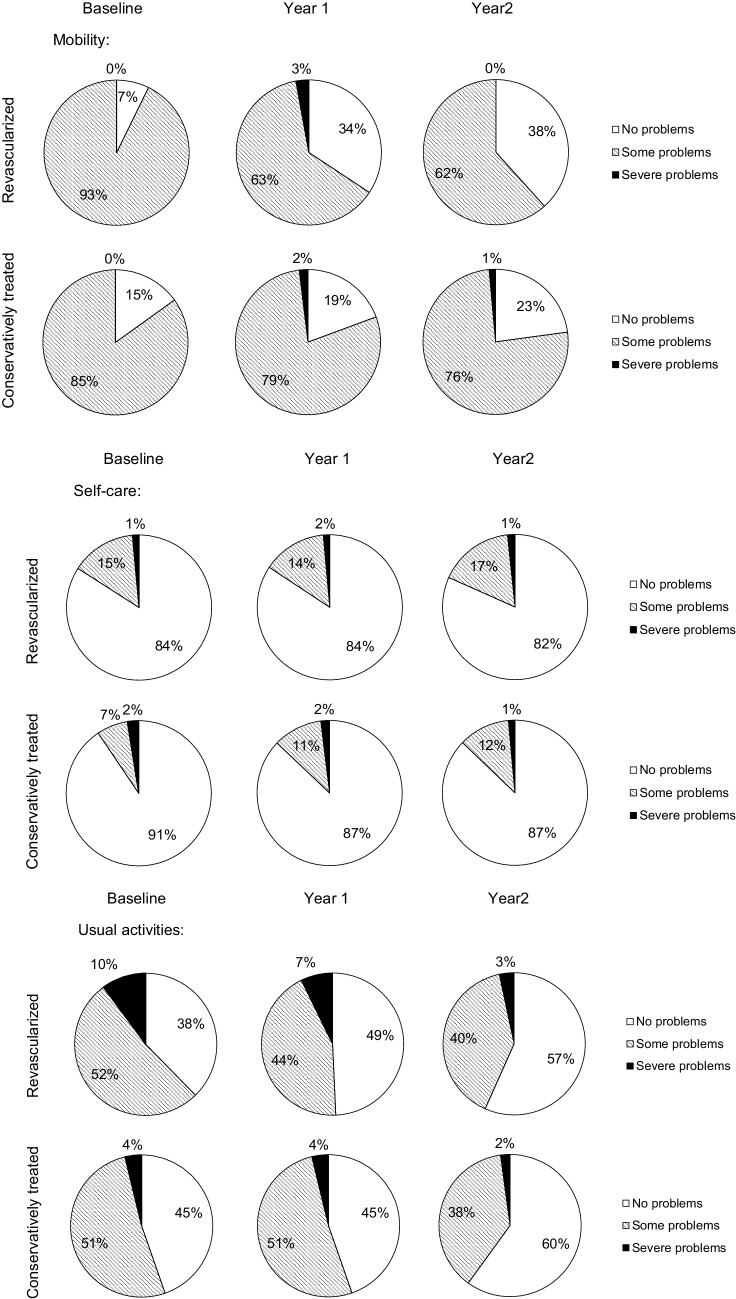

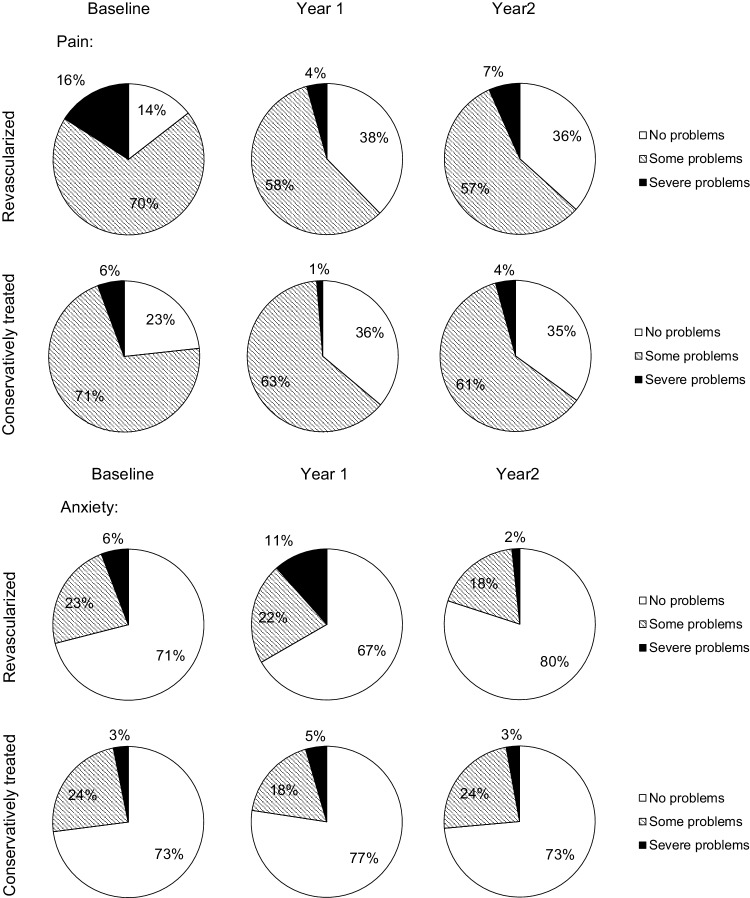

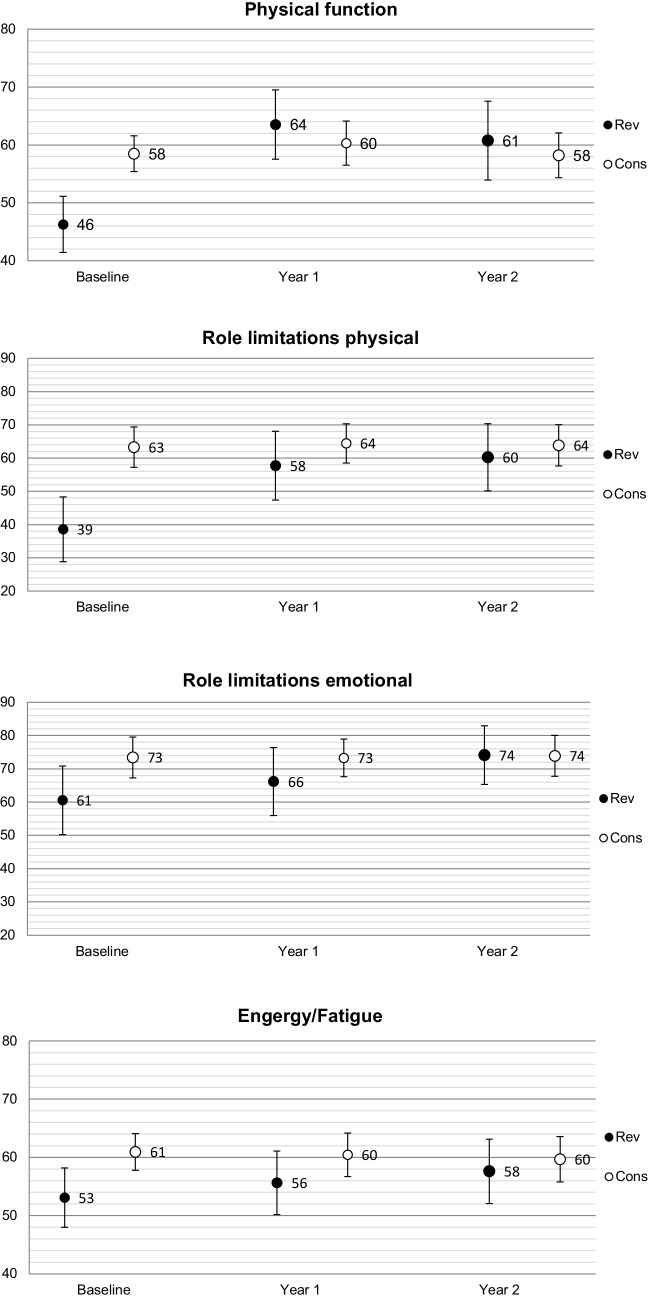

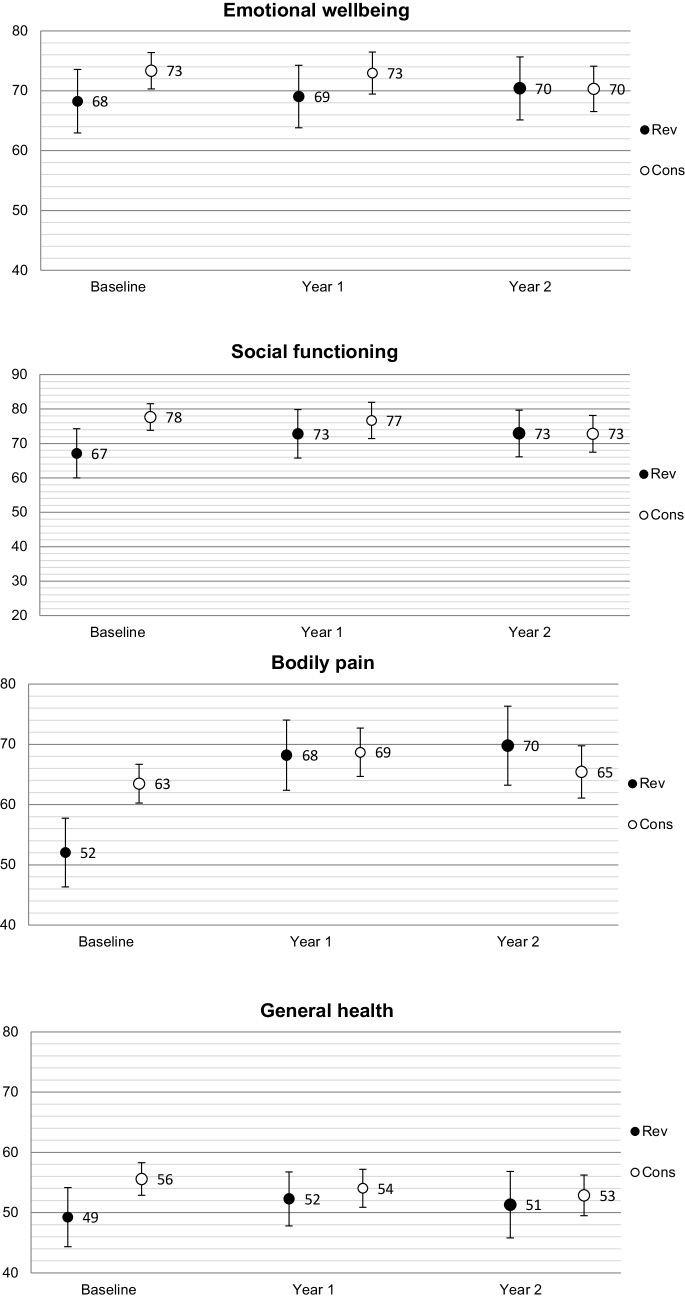

The descriptive system of the EQ-5D revealed that QoL gains after revascularisation were driven by increasing proportions of patients reporting ‘no problems’ with pain/discomfort, mobility and usual activities (see Fig. 3 in Appendix 1). All SF-6D domain scores increased, the largest increases were observed in the domains physical functioning, role limitations physical and pain (see Fig. 4 in Appendix 1).

Fig. 3.

EQ-5D domains over time

Fig. 4.

a–h SF-36 domain scores over time* Rev Revascularized, Cons Conservative treatment

Propensity score matching resulted in improved covariate balance between revascularised and conservatively treated patients. The propensity score and overviews of covariate balance after matching are presented in Appendix 3. Therefore, matched data were used in the ANCOVA analyses. The ANCOVA model (Table 3) showed that baseline QoL is a covariate of QoL change after treatment. All other baseline patient characteristics (see Table 1 for characteristics) and treatment type were not significant covariates. The models indicated QoL gain after treatment was larger in patients with low baseline QoL.

Table 3.

ANCOVA analysis: coefficients of QoL change baseline – year 1, and baseline-year 2

| Model coefficients | SF-6D | EQ-5D | VAS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Sig. | B | SE | Sig. | B | SE | Sig. | |

| Year 1 | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.427 | 0.108 | 0.001 | 0.529 | 0.074 | 0.000 | 0.543 | 0.119 | 0.000 |

| Conservative treatment | − 0.055 | 0.042 | 0.205 | − 0.038 | 0.057 | 0.506 | 0.002 | 0.072 | 0.978 |

| Baseline SF-6D | − 0.587 | 0.163 | 0.001 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Baseline EQ-5D | – | – | – | − 0.774 | 0.119 | 0.000 | – | – | – |

| Baseline VAS | – | – | – | – | – | – | − 0.817 | 0.211 | 0.002 |

| Year 2 | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.394 | 0.139 | 0.008 | 0.637 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.481 | 0.157 | 0.007 |

| Conservative treatment | − 0.035 | 0.038 | 0.360 | − 0.064 | 0.077 | 0.416 | − 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.630 |

| Rest pain | − 0.030 | 0.047 | 0.516 | − 0.167 | 0.073 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.095 | 0.996 |

| Baseline SF-6D | − 0.564 | 0.200 | 0.008 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Baseline EQ-5D | – | – | – | − 0.870 | 0.117 | 0.000 | – | – | – |

| Baseline VAS | – | – | – | – | – | – | − 0.713 | 0.219 | 0.005 |

This analysis is based on propensity score-matched data

B beta-coefficient, Sig. significance, SE standard error

Post hoc analyses of the ANCOVA models (Table 4) produced PS-matched EMMs of revascularisation and conservative treatment at year 1. EMMs after revascularisation are consistently positive, while those of conservative treatment are positive and negative (see Fig. 2b in Appendix 1). EMMs of revascularisation and conservative treatment do not differ significantly. Between the metrics, EMMs and mean differences vary in magnitude, EQ-5D EMMs and SF-6D mean differences are largest, VAS EMMs are lowest and the mean difference is negative. Scenario analyses confirm these observations, only the complete case scenario produced scores somewhat different (see Appendix 4).

Table 4.

ANCOVA post hoc analysis: estimated marginal means of treatment at year 1 and year 2

| Estimated marginal means (SE) | P value | R2a | Adjusted R2a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rev | Cons | Difference | ||||

| Year 1 | ||||||

| SF-6D | 0.038 (0.021) | − 0.017 (0.042) | 0.055 (0.042) | 0.205 | 0.141–0.382 | 0.128–0.373 |

| EQ-5D | 0.077 (0.041) | 0.038 (0.040) | 0.038 (0.057) | 0.506 | 0.308–0.551 | 0.398–0.545 |

| VAS | 0.019 (0.053) | 0.021 (0.048) | − 0.002 (0.072) | 0.978 | 0.227–0.461 | 0.216–0.453 |

| Year 2 | ||||||

| SF-6D | 0.015 (0.025) | − 0.020 (0.032) | 0.035 (0.038) | 0.360 | 0.050–0.251 | 0.026–0.231 |

| EQ-5D | 0.077 (0.043) | 0.013 (0.060) | 0.064 (0.077) | 0.416 | 0.354–0.499 | 0.338–0.487 |

| VAS | 0.027 (0.036) | − 0.004 (0.055) | 0.031 (0.063) | 0.630 | 0.059–0.420 | 0.035–0.405 |

Rev revascularised, Con conservative treatment, SE standard error

aR2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Sustainability of and heterogeneity in revascularisation effect during the second year

As seen at 1-year follow-up, patients revascularised in year one reported less problems with pain/discomfort, mobility and usual activities in the EQ-5D (see Fig. 3 in Appendix 1). All SF-6D domain scores were increased compared to baseline and year one follow-up except for physical function, which decreased compared to year one follow-up but remained increased compared to baseline (see Fig. 4 in Appendix 1).

Baseline QoL and rest pain are significant covariates of QoL change after treatment, while all other baseline patient characteristics and treatment group were not significant covariates (Table 3). QoL gains after treatment are larger in patients with low baseline QoL, and lower in patients with rest pain.

As at year 1, year 2 EMMs after revascularisation are consistently positive and those of conservative treatment are positive and negative (see Fig. 2c in Appendix 1). Unlike in year 1, all mean differences are positive, yet not statistically significant (Table 4). In comparison to year 1, EMMs of revascularisation were increased, stagnated and decreased measured by SF-6D, EQ-5D and VAS, respectively. Between the metrics, EMMs and mean differences vary in magnitude, the EQ-5D has the largest scores. Scenario analyses also confirm these observations and show similar scores, only the complete case scenario produced scores somewhat different (see Appendix 4).

Discussion

Main findings

A year after diagnosis, the effect of revascularisation on QoL is insignificantly positive, and is influenced by baseline QoL. The effect of revascularisation is insignificantly larger than the effect of conservative treatment. Two years after diagnosis, the positive effect of revascularisation on QoL is sustained. Factors influencing the maintained effect of revascularisation on QoL are baseline QoL and rest pain, the latter only on EQ-5D scores. Compared to the first year, a decreased, stable and increased revascularisation effect is depicted by SF-6D, EQ-5D and VAS, respectively. Magnitude of revascularisation effect is generally largest when considering the EQ-5D.

Interpretation

We found positive effects of revascularisation on QoL at years 1 and 2 measurements. This is in line with literature reporting QoL gains of 0.07 to 0.19 measured with the EQ-5D [10, 37, 38], significant increases in all SF-36 domains [11] and a VAS gain of 0.12 1 year after revascularisation [38]. Moreover, EQ-5D, VAS and SF-36 domain scores 2 years after PAD diagnosis were in line with long-term follow-up scores measured 11 years after revascularisation in van Hattum et al. [39]. Regression analysis had previously shown age, BMI, education, severity of disease and baseline general health to predict SF-36 domain scores 1 year after revascularisation [11, 40]. A different study had found age and diabetes to correlate with SF-36 scores between 1 and 7 years after revascularisation or amputation for PAD; rest pain was tested and found to be insignificant, QoL before the intervention was not tested as a predictor [40]. Differences in patient characteristics, outcome measures and variables in the regression analyses hamper the comparison of these results.

As a result of adaptation and coping, patient VAS scores, as estimates of a patient’s own QoL, tend to be higher than EQ-5D scores which reflect the public’s preferences for a patient’s health state description [12, 41, 42]. Our results are in line with these expectations. Furthermore, the mean difference between baseline EQ-5D and SF-6D in our study (EQ-5D 0.052 points larger than SF-6D) was similar to that in other patient populations [43]. The observation that the effect of revascularisation on QoL was larger measured by the EQ-5D might be explained by a floor effect of the SF-6D. The SF-6D, as it was designed to assess QoL in the general population, tends to produce relatively high utility values in patients with a larger disease burden [5, 39]. Figure 5 in Appendix 1 shows that in our sample, values below 0.55 were rare. This floor effect can then cause decreased sensitivity in health states of lower QoL [5, 14, 27, 43–45]. Consistently, it has been hypothesised that QoL valued by the patients themselves have a ceiling effect and reduced discriminative capabilities, which might explain low VAS change scores [12]. Figure 5 in Appendix 1 indicates scores above 0.9 were rare. However, previous studies also identified a potential weakness of the EQ-5D, the overestimation of QoL due to the avoidance of the third and most severe level [29, 43]. In other populations, less than 1% made use of level 3 of the domain ‘mobility’. Avoidance of mobility level 3 can cause an insensitivity of the EQ-5D to improvements in mobility. Figure 3 shows that in our study, only 0–3% of patients responded with level 3 in this domain. Insensitivity to change, however, was not indicated in our results considering mobility was a significant driver of QoL change after treatment. Moreover, a previous literature review concluded the EQ-5D to be more sensitive to change than other generic measures in PAD patients [19], results that we confirmed with the comparatively large estimated marginal means of treatment and the comparatively large difference between treatment groups.

Strengths and weaknesses

A first strength of this study is the selection of participants; the study population consisting of patients referred to the vascular surgery department for PAD diagnosis reflects the spectrum of PAD patients, including patients with varying medical history and PAD severity. Our outcomes are likely generalisable to PAD patients in secondary care overall. Secondly, by using PS matching, the observational data were resampled to allow for comparisons of revascularised and conservatively treated patients, thereby enabling comparisons of treatment effect. Thirdly, by analysing three widely used QoL metrics, one of them being the current standard in assessing QoL for economic evaluations in, for instance, the Netherlands [28] and the United Kingdom [46], and comparing their scores and performances, this study provides well-needed insight into the strengths and weaknesses as well as the suitability of the metrics for economic evaluations regarding treatment of PAD.

The study also suffered from several limitations. The inclusion time just short of 5 years may have allowed for techniques to evolve over time so that patients might have been exposed to varying treatment methods. Expert opinion indicated these developments were not substantial at the study site. Patients using coagulation-altering medication were excluded. Given these medications will be prescribed for atrial fibrillation, a condition vastly affecting QoL [47–49], the excluded patients might be a subgroup with especially low QoL. As a result, our QoL estimates may be an overestimation of the QoL in the total incident PAD population. Another weakness is that, although this is extremely unlikely given the patients’ long treatment records in the participating hospitals, we cannot rule out that patients could have received revascularisation elsewhere that was not reported. Our research also highlighted several implications for further research. Given the variability of revascularisation effect after accounting for a number of patient characteristics, further research should identify patient characteristics of influence, e.g. socioeconomic determinants such as SES, housing and activity level in daily life, or further PAD-specific determinants such as length and location of the occlusion. The relatively small sample size, especially of revascularised patients, may be a weakness of the study as it may have caused relationships or differences that are present to be statistically insignificant. In this respect, it is important to recall that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence [50]. And lastly, the umbrella term (peripheral) revascularisation summarises a number of interventions aimed at restoring blood flow to the leg. Considering the on-going discussion about patency of endovascular vs. surgical revascularisation [51], further research should compare the sustainability of QoL gains acquired by different revascularisation techniques. Data from randomised controlled trials would furthermore negate the need for propensity score matching as an adjustment for confounding by indication, and would thereby enable stronger conclusions about the comparison of treatments.

Conclusion

The findings of this study show that conservative and invasive treatment both have a positive effect on QoL, and the effect of invasive treatment is sustained over 2 years. Significance tests show no difference between the treatment options. The results of our analyses confirmed advantages of the EQ-5D in detecting change over time and differences between groups. Our results therefore indicate that EQ-5D utilities may be most suitable for QoL measurement in patients with PAD, and support the preferential application of the EQ-5D in this population. The finding that the magnitude of revascularisation effect is influenced by baseline QoL may be relevant for clinical decision making, as it can give an a priori estimation of the expected QoL gain in individual patients.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the discussants and attendees of the Lowlands Health Economic Study Group Conference 2018 for an interesting and fruitful discussion of the manuscript. Furthermore, we want to thank all patients, nurses and clinicians involved in the INCOAG study for their significant contributions.

Appendix 1: Additional analyses baseline

Appendix 2: Additional information

List of exclusion criteria:

PAD diagnosis more than 3 months prior to study inclusion,

cardiovascular or arterial interventions within the past 6 months,

(unstable) angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, stroke or heart failure within the past 3 months,

known coagulation disorders,

anticoagulant medication use (e.g. Vitamin K antagonists, direct factor Xa-inhibitors and factor II-inhibitors, heparin),

chronic inflammatory diseases,

active malignancies,

repeatedly failed venipunctures,

being underage,

not meeting the inclusion criteria.

List of events summarised in the term cardiovascular events:

transient ischemic attack,

stroke,

other cerebral events,

angina pectoris,

myocardial infarction,

other ischemic events,

coronary revascularisation,

abdominal aortic aneurysm,

other artery diseases.

Appendix 3: Propensity score matching

See Table 8.

Table 8.

Group characteristics after propensity score matching for year 1

| Characteristic | Pre-matching pooled | Post-matching pooled | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rev | Cons | Rev | Cons | |

| Quality of life | ||||

| SF-6D baseline | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| EQ-5D baseline | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.60 |

| VAS baseline | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Male gender (%) | 67.14 | 63.52 | 65.48 | 67.33 |

| Currently smoking (%) | 58.57 | 50.82 | 58.24 | 57.95 |

| Age (± SD) | 63.97 | 66.53 | 64.76 | 64.44 |

| Body mass index (± SD) | 26.11 | 26.76 | 25.88 | 27.24 |

| Disease severity | ||||

| Fontaine I (%) | 1.43 | 5.03 | 1.42 | 4.40 |

| Fontaine IIa (%) | 47.14 | 64.84 | 49.72 | 55.40 |

| Fontaine IIb (%) | 45.71 | 28.49 | 43.04 | 38.21 |

| Fontaine III (%) | 2.86 | 1.51 | 2.84 | 1.99 |

| Fontaine IV (%) | 2.86 | 0.13 | 2.98 | 0.00 |

| Progressive symptoms (%) | 74.29 | 40.25 | 71.45 | 75.00 |

| Rest pain (%) | 31.71 | 11.07 | 29.40 | 17.19 |

| Complaints in daily life (%) | 75.00 | 47.36 | 74.29 | 73.15 |

| Claudication distance < 100 m (%) | 45.29 | 18.36 | 42.61 | 44.89 |

| Ankle brachial index (± SD) | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Stroke (%) | 17.14 | 10.69 | 17.61 | 16.48 |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 7.14 | 14.47 | 7.95 | 9.23 |

| No diabetes (%) | 84.29 | 82.39 | 85.37 | 77.70 |

| Untreated diabetes (%) | 1.43 | 2.52 | 1.42 | 8.66 |

| Diabetes mellitus II (%) | 14.29 | 10.69 | 13.21 | 9.52 |

| Diabetes mellitus I (%) | 0.00 | 4.40 | 0.00 | 4.12 |

| Hypertension (%) | 52.86 | 54.72 | 50.85 | 59.80 |

| Cholesterol-lowering drug use (%) | 84.29 | 81.13 | 84.23 | 79.83 |

| Elevated D-Dimer (%) | 32.86 | 30.82 | 32.53 | 30.82 |

| Impaired kidney function (%) | 12.86 | 24.53 | 13.78 | 14.06 |

| Malignancies (%) | 7.14 | 10.06 | 7.39 | 6.39 |

Rev revascularised, Cons conservatively treated, SD standard deviation

List of parameters included in the propensity score:

Progressive symptoms;

Complaints in daily life;

Claudication distance;

Baseline SF-6D;

- Domains of the SF-36:

- Physical Function;

- Limitations Physical;

- Bodily Pain;

Age;

Myocardial infarction;

Currently smoking.

Appendix 4: Scenario analyses

See Tables 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18.

Table 9.

Crude scores with propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 1

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.042 (0.022) | − 0.021 (0.043) | 0.063 (0.043) | 0.158 |

| EQ-5D | 0.089 (0.047) | 0.026 (0.050) | 0.064 (0.071) | 0.377 |

| VAS | 0.023 (0.054) | 0.018 (0.059) | 0.005 (0.082) | 0.951 |

Rev revascularized, Cons conservative treatment

Table 10.

EMMs without propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 1

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.027 (0.020) | − 0.004 (0.012) | 0.031 (0.022) | 0.155 | 0.176–0.228 | 0.168–0.222 |

| EQ5D | 0.038 (0.035) | 0.030 (0.025) | 0.008 (0.041) | 0.842 | 0.259–0.438 | 0.252–0.433 |

| VAS | 0.003 (0.045) | 0.013 (0.020) | − 0.010 (0.051) | 0.851 | 0.264–0.410 | 0.257–0.405 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.049 (0.020) | − 0.013 (0.014) | 0.062 (0.023) | 0.008 |

| EQ-5D | 0.090 (0.046) | 0.008 (0.026) | 0.083 (0.047) | 0.084 |

| VAS | 0.034 (0.048) | − 0.001 (0.025) | 0.035 (0.055) | 0.527 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 11.

EMMs without propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 1

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.033 (0.019) | 0.006 (0.012) | 0.027 (0.021) | 0.199 | 0.215–0.252 | 0.207–0.244 |

| EQ-5D | 0.031 (0.035) | 0.031 (0.026) | 0.000 (0.042) | 0.992 | 0.254–0.447 | 0.247–0.442 |

| VAS | 0.006 (0.046) | 0.027 (0.020) | − 0.020 (0.053) | 0.703 | 0.310–0.459 | 0.304–0.454 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.057 (0.021) | − 0.004 (0.013) | 0.060 (0.023) | 0.009 |

| EQ-5D | 0.087 (0.048) | 0.008 (0.027) | 0.079 (0.052) | 0.132 |

| VAS | 0.049 (0.050) | 0.009 (0.025) | 0.041 (0.056) | 0.477 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 12.

EMMs without propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 1

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.052 (0.023) | 0.021 (0.016) | 0.031 (0.029) | 0.274 | 0.102 | 0.084 |

| EQ-5D | 0.045 (0.029) | 0.030 (0.020) | 0.015 (0.036) | 0.671 | 0.333 | 0.322 |

| VAS | − 0.010 (0.027) | 0.003 (0.019) | − 0.014 (0.033) | 0.686 | 0.126 | 0.113 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.066 (0.026) | 0.015 (0.015) | 0.042 (0.025) | 0.073 |

| EQ-5D | 0.085 (0.040) | 0.012 (0.022) | 0.053 (0.043) | 0.111 |

| VAS | 0.007 (0.035) | − 0.005 (0.018) | 0.009 (0.031) | 0.726 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 13.

EMMs with propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 1

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.015 (0.025) | − 0.020 (0.032) | 0.035 (0.038) | 0.360 | 0.050–0.251 | 0.026–0.231 |

| EQ-5D | 0.077 (0.043) | 0.013 (0.060) | 0.064 (0.077) | 0.416 | 0.354–0.499 | 0.338–0.487 |

| VAS | 0.027 (0.036) | − 0.004 (0.055) | 0.031 (0.063) | 0.630 | 0.059–0.420 | 0.035–0.405 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.018 (0.026) | − 0.023 (0.032) | 0.040 (0.038) | 0.292 |

| EQ-5D | 0.083 (0.054) | 0.007 (0.068) | 0.076 (0.092) | 0.417 |

| VAS | 0.037 (0.054) | − 0.014 (0.064) | 0.050 (0.077) | 0.519 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 14.

EMMs with propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 2

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.018 (0.026) | − 0.023 (0.032) | 0.040 (0.038) | 0.292 |

| EQ-5D | 0.083 (0.054) | 0.007 (0.068) | 0.076 (0.092) | 0.417 |

| VAS | 0.037 (0.054) | − 0.014 (0.064) | 0.050 (0.077) | 0.519 |

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 15.

EMMs without propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 2

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.016 (0.025) | − 0.035 (0.016) | 0.050 (0.030) | 0.093 | 0.078–0.108 | 0.065–0.095 |

| EQ-5D | 0.068 (0.038) | 0.011 (0.023) | 0.057 (0.044) | 0.198 | 0.301–0.435 | 0.291–0.427 |

| VAS | 0.019 (0.038) | − 0.015 (0.026) | 0.034 (0.045) | 0.448 | 0.164–0.307 | 0.152–0.297 |

| Rev rude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.051 (0.020) | − 0.015 (0.014) | 0.067 (0.025) | 0.007 |

| EQ-5D | 0.084 (0.047) | 0.010 (0.028) | 0.074 (0.049) | 0.136 |

| VAS | 0.040 (0.046) | − 0.002 (0.026) | 0.042 (0.053) | 0.433 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 16.

EMMs without propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 2

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.021 (0.025) | − 0.021 (0.017) | 0.041 (0.030) | 0.167 | 0.074–0.102 | 0.058–0.087 |

| EQ-5D | 0.062 (0.043) | 0.015 (0.024) | 0.048 (0.049) | 0.327 | 0.304–0.452 | 0.292–0.443 |

| VAS | 0.021 (0.041) | − 0.012 (0.028) | 0.033 (0.047) | 0.476 | 0.156–0.341 | 0.141–0.330 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.055 (0.022) | 0.000 (0.014) | 0.055 (0.025) | 0.031 |

| EQ-5D | 0.072 (0.053) | 0.012 (0.030) | 0.060 (0.054) | 0.270 |

| VAS | 0.043 (0.051) | 0.005 (0.026) | 0.037 (0.058) | 0.523 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 17.

EMMs without propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 2

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.001 (0.033) | 0.011 (0.021) | − 0.010 (0.040) | 0.800 | 0.075 | 0.045 |

| EQ-5D | 0.031 (0.033) | 0.038 (0.023) | − 0.007 (0.040) | 0.863 | 0.391 | 0.376 |

| VAS | 0.005 (0.027) | − 0.011 (0.021) | 0.016 (0.035) | 0.643 | 0.060 | 0.036 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.012 (0.046) | 0.009 (0.016) | 0.003 (0.048) | 0.951 |

| EQ-5D | 0.059 (0.048) | 0.028 (0.025) | 0.031 (0.054) | 0.563 |

| VAS | 0.010 (0.032) | − 0.015 (0.019) | 0.024 (0.035) | 0.482 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Table 18.

EMMs with propensity score matching, QoL change baseline to year 2

| Rev EMM (SE) | Cons EMM (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.015 (0.025) | − 0.020 (0.032) | 0.035 (0.038) | 0.360 | 0.050–0.251 | 0.026–0.231 |

| EQ-5D | 0.077 (0.043) | 0.013 (0.060) | 0.064 (0.077) | 0.416 | 0.354–0.499 | 0.338–0.487 |

| VAS | 0.027 (0.036) | − 0.004 (0.055) | 0.031 (0.063) | 0.630 | 0.059–0.420 | 0.035–0.405 |

| Rev crude score (SE) | Cons crude score (SE) | Mean difference (SE) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-6D | 0.018 (0.026) | − 0.023 (0.032) | 0.040 (0.038) | 0.292 |

| EQ-5D | 0.083 (0.054) | 0.007 (0.068) | 0.076 (0.092) | 0.417 |

| VAS | 0.037 (0.054) | − 0.014 (0.064) | 0.050 (0.077) | 0.519 |

R2 are presented as ranges due to the presence of multiple imputation datasets

Rev revascularised, Cons conservative treatment, EMM estimated marginal mean

Year 1

Scenario 1: Unmatched sample

Scenario 2: Unmatched sample, exclusively using patients without cardiovascular events during follow-up

Scenario 3: Unmatched sample, exclusively using complete cases

Scenario 4: Matched sample, excluding patients revascularised in the second half of the first follow-up year

Year 2

Scenario 1: Unmatched sample

Scenario 2: Unmatched sample, exclusively using patients without cardiovascular events during follow-up

Scenario 3: Unmatched sample, exclusively using complete cases

Scenario 4: Matched sample, excluding patients revascularised in the second half of the first follow-up year

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

SP, BR, AC, JD and MJ have nothing to disclose. RO reports personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Pfizer/BMS, outside the submitted work. HC reports grants from Bayer, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Pfizer/BMS, personal fees from Stago, grants from Leo Pharma, outside the submitted work and HC is an unpaid chairman of the board of the Dutch Federation of Anticoagulation clinics.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FGR. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II) Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2007;45(1):5–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowkes FGR, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, Norman PE, Sampson UKA, Williams LJ, Mensah GA, Criqui MH. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aboyans, V., Ricco, J.-B., Bartelink, M.-L. E. L., Björck, M., Brodmann, M., Cohnert, T., Collet, J.-P., Czerny, M., De Carlo, M., Debus, S., Espinola-Klein, C., Kahan, T., Kownator, S., Mazzolai, L., Naylor, A. R., Roffi, M., Röther, J., Sprynger, M., Tendera, M., Tepe, G., Venermo, M., Vlachopoulos, C., & Desormais, I. (2017). 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS)Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J, ehx095-ehx095. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Breek JC, Hamming JF, De Vries J, Aquarius AE, van Henegouwen B. Quality of life in patients with intermittent claudication using the World Health Organisation (WHO) questionnaire. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2001;21(2):118–122. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordanstig J, Taft C, Hensater M, Perlander A, Osterberg K, Jivegard L. Improved quality of life after 1 year with an invasive versus a noninvasive treatment strategy in claudicants: One-year results of the Invasive Revascularization or Not in Intermittent Claudication (IRONIC) Trial. Circulation. 2014;130(12):939–947. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink M-L, Baumgartner I, Clément D, Collet J-P, Cremonesi A, De Carlo M, Erbel R, Fowkes FGR, Heras M, Kownator S, Minar E, Ostergren J, Poldermans D, Riambau V, Roffi M, Röther J, Sievert H, van Sambeek M, Zeller T, Bax J, Auricchio A, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Poldermans D, Popescu B, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Kolh P, Torbicki A, Agewall S, Blinc A, Bulvas M, Cosentino F, De Backer T, Gottsäter A, Gulba D, Guzik TJ, Jönsson B, Késmárky G, Kitsiou A, Kuczmik W, Larsen ML, Madaric J, Mas J-L, McMurray JJV, Micari A, Mosseri M, Müller C, Naylor R, Norrving B, Oto O, Pasierski T, Plouin P-F, Ribichini F, Ricco J-B, Ruilope L, Schmid J-P, Sprynger M, Tiefenbacher C, Tsioufis C, Van Damme H. ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases. European Heart Journal. 2011;32(32):28512906. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds, M. R., Apruzzese, P., Galper, B. Z., Murphy, T. P., Hirsch, A. T., Cutlip, D. E., Mohler, E. R., Regensteiner, J. G., & Cohen, D. J. (2014). Cost-effectiveness of supervised exercise, stenting, and optimal medical care for claudication: Results from the Claudication: Exercise Versus Endoluminal Revascularization (CLEVER) trial. Journal of the American Heart Association, 3(6), e001233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Wann-Hansson C, Hallberg IR, Risberg B, Lundell A, Klevsgard R. Health-related quality of life after revascularization for peripheral arterial occlusive disease: Long-term follow-up. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;51(3):227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safley DM, House JA, Laster SB, Daniel WC, Spertus JA, Marso SP. Quantifying improvement in symptoms, functioning, and quality of life after peripheral endovascular revascularization. Circulation. 2007;115(5):569–575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlajinac H, Marinkovic J, Tanaskovic S, Kocev N, Radak D, Davidovic D, Maksimovic M. Quality of life after peripheral bypass surgery: A 1 year follow-up. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2015;127(5–6):210–217. doi: 10.1007/s00508-014-0663-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Wit GA, Busschbach JJV, De Charro FT. Sensitivity and perspective in the valuation of health status: Whose values count? Health Economics. 2000;9(2):109–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(200003)9:2<109::aid-hec503>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blieden M, Smith D, Becker BT, Paoli CJ, Gandra SR. A systematic review of cardiovascular event utilities In Europe. Value in Health. 2015;18(7):A397. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joore M, Brunenberg D, Nelemans P, Wouters E, Kuijpers P, Honig A, Willems D, de Leeuw P, Severens J, Boonen A. The impact of differences in EQ-5D and SF-6D utility scores on the acceptability of cost–utility ratios: results across five trial-based cost–utility studies. Value in Health. 2010;13(2):222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chetter, I. C., Spark, J. I., Dolan, P., Scott, D. J. A., & Kester, R. C. (1997). Quality of life analysis in patients with chronic lower limb ischaemia: Suggestions for European standardisation. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mehta T, Subramaniam AV, Chetter I, McCollum P. Disease-specific quality of life assessment in intermittent claudication: Review. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2003;25(3):202–208. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klevsgård, R., Fröberg, B. L., Risberg, B., & Hallberg, I. R. (2002). Nottingham Health Profile and Short Form 36 Health Survey questionnaire in patients with chronic lower limb ischaemia. Before and after revascularization. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Poku E, Duncan R, Keetharuth A, Essat M, Phillips P, Woods HB, Palfreyman S, Jones G, Kaltenthaler E, Michaels J. Patient-reported outcome measures in patients with peripheral arterial disease: A systematic review of psycho metric properties. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2016;14:161. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0563-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyer MTD, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss L, Golzarian J, Gornik HL, Jaff MR, Moneta GL, Olin JW, Stanley JC, White CJ, White JV, Zierler RE. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61(14):1555–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardman RL, Jazaeri O, Yi J, Smith M, Gupta R. Overview of classification systems in peripheral artery disease. Seminars in Interventional Radiology. 2014;31(4):378–388. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss LK, Golzarian J, Gornik HL, Halperin JL, Jaff MR, Moneta GL, Olin JW, Stanley JC, White CJ, White JV, Zierler RE, SocietyCardiovascular A, Interventions 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease (updating the 2005 guideline): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58(19):2020–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. (2000). Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 894, i–xii, 1–253. [PubMed]

- 24.Romero J-M, Bover J, Fite J, Bellmunt S, Dilmé J-F, Camacho M, Vila L, Escudero J-R. The modification of diet in renal disease 4-calculated glomerular filtration rate is a better prognostic factor of cardiovascular events than classical cardiovascular risk factors in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2012;56(5):1324–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PDA, Essink-Bot M-L, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, Sprangers MAG, Velde A, Verrips E. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 health survey in community and chronic disease populations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1055–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21(2):271–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamers LM, Bouwmans CAM, van Straten A, Donker MCH, Hakkaart L. Comparison of EQ-5D and SF-6D utilities in mental health patients. Health Economics. 2006;15(11):1229–1236. doi: 10.1002/hec.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zorginstituut Nederland. (2016). Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare.

- 29.Lamers LM, McDonnell J, Stalmeier PFM, Krabbe PFM, Busschbach JJV. The Dutch tariff: Results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Economics. 2006;15(10):1121–1132. doi: 10.1002/hec.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EuroQol Group EuroQol: A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allison PD. Missing data. New York: SAGE Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science. 2010;25(1):1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310(6973):170–170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale, Calif.) 2016;6(2):227. doi: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devine, E. B., Alfonso-Cristancho, R., Yanez, N., et al. (2016). Effectiveness of a medical vs revascularization intervention for intermittent leg claudication based on patient-reported outcomes. JAMA Surgery, 151(10), e162024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Egberg L, Mattiasson AC, Ljungstrom KG, Styrud J. Health-related quality of life in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing percutaneous transluminal angioplasty: a prospective one-year follow-up. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2010;28(2):72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Hattum ES, Tangelder MJ, Lawson JA, Moll FL, Algra A. The quality of life in patients after peripheral bypass surgery deteriorates at long-term follow-up. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2011;53(3):643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holtzman J, Caldwell M, Walvatne C, Kane R. Long-term functional status and quality of life after lower extremity revascularization. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 1999;29(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McPherson K, Myers J, Taylor WJ, McNaughton HK, Weatherall M. Self-valuation and societal valuations of health state differ with disease severity in chronic and disabling conditions. Medical Care. 2004;42(11):1143–1151. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Versteegh MM, Brouwer WBF. Patient and general public preferences for health states: A call to reconsider current guidelines. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;165:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A, Busschbach J. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Economics. 2004;13(9):873–884. doi: 10.1002/hec.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smolderen, K. G., van Zitteren, M., Jones, P. G., Spertus, J. A., Heyligers, J. M., Nooren, M. J., Vriens, P. W., & Denollet, J. (2015). Long-term prognostic risk in lower extremity peripheral arterial disease as a function of the number of peripheral arterial lesions. Journal of the American Heart Association, 4(10), e001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Szende Á, Svensson K, Ståhl E, Mészáros Á, Berta GY. Psychometric and utility-based measures of health status of asthmatic patients with different disease control level. PharmacoEconomics. 2004;22(8):537–547. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Position statement on use of the EQ-5D-5L valuation set.

- 47.Dorian P, Jung W, Newman D, Paquette M, Wood K, Ayers GM, Camm J, Akhtar M, Luderitz B. The impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation: implications for the assessment of investigational therapy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;36(4):1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suman-Horduna I, Roy D, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Lespérance F, Blondeau L, Dorian P, Khairy P. Quality of life and functional capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61(4):455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jenkins LS, Brodsky M, Schron E, Chung M, Rocco TJ, Lader E, Constantine M, Sheppard R, Holmes D, Mateski D, Floden L, Prasun M, Greene HL, Shemanski L. Quality of life in atrial fibrillation: The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. American Heart Journal. 2005;149(1):112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311(7003):485–485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, Bjorck M, Brodmann M, Cohnert T, Collet JP, Czerny M, De Carlo M, Debus S, Espinola-Klein C, Kahan T, Kownator S, Mazzolai L, Naylor AR, Roffi M, Rother J, Sprynger M, Tendera M, Tepe G, Venermo M, Vlachopoulos C, Desormais I. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries. European Heart Journal. 2018;39(9):763–816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]