Highlights

-

•

Total physical activity is inversely associated with chronic back conditions.

-

•

At least 300 min/week of moderate intensity or 30 min/week of vigorous intensity activities are associated with a low odds of having chronic back conditions.

-

•

Medium domestic activity, football/rugby, or running/jogging are inversely associated with chronic back conditions.

-

•

High-level manual domestic activity is associated with a higher odds of having chronic back conditions.

-

•

High-level sport/exercise is associated with a low odds of having chronic back conditions, and low-level sport/exercise is associated with high odds of having chronic back conditions.

Keywords: Activity, Chronic low back pain, Chronic musculoskeletal conditions, Epidemiology, Exercise

Abstract

Background

Little is known about the association between different types of physical activity (PA) and chronic back conditions (CBCs) at the population level. We investigated the association between levels of total and type-specific PA participation and CBCs.

Methods

The sample comprised 60,134 adults aged ≥16 years who participated in the Health Survey for England and Scottish Health Survey from 1994 to 2008. Multiple logistic regression models, adjusted for potential confounders, were used to examine the association between total and type-specific PA volume (walking, domestic activity, sport/exercise, cycling, football/rugby, running/jogging, manual work, and housework) and the prevalence of CBCs.

Results

We found an inverse association between total PA volume and prevalence of CBCs. Compared with inactive participants, the fully adjusted odds ratio (OR) for very active participants (≥15 metabolic equivalent h/week) was 0.77 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.69–0.85). Participants reporting ≥300 min/week of moderate-intensity activity and ≥75 min/week of vigorous-intensity activity had 24% (95%CI: 6%–39%) and 21% (95%CI: 11%–30%) lower odds of CBCs, respectively. Higher odds of CBCs were observed for participation in high-level manual domestic activity (OR = 1.22; 95%CI: 1.00–1.48). Sport/exercise was associated with CBCs in a less consistent manner (e.g., OR = 1.18 (95%CI: 1.06–1.32) for low levels and OR = 0.82 (95%CI: 0.72–0.93) for high levels of sport/exercise).

Conclusion

PA volume is inversely associated with the prevalence of CBCs.

1. Introduction

Chronic back conditions (CBCs) are common and impose a major burden on healthcare services. Low back pain (LBP), in particular, is one of the most common conditions encountered in clinical practice and remains a major health problem globally.1 For example, in 2016, LBP was the leading cause of years lived with disability.2 Moreover, the lifetime prevalence of LBP is reported to be as high as 84% worldwide3 and between 58% and 62% in the UK.4, 5, 6 In addition, the point prevalence of chronic pain in the UK is reported to be as high as 51%.7

CBCs encompass a range of complaints resulting in impairments that restrict people's function. CBCs include back and neck pain, and other complaints affecting the back such as back trouble, curvature of the spine, disc trouble, lumbago, inflammation of the spinal joints, spondylitis, and spondylosis. LBP, for example, adversely affects individuals, their families, communities, and governments globally.8 The economic burden of LBP is increasing and includes increasing days of absenteeism from work, loss of productivity, and cost of treatment.9 In addition, the occurrence and chronicity of LBP have been associated with various individual, psychosocial, and occupational risk factors such as low education level, high levels of pain, depression, anxiety, physical limitations, and job dissatisfaction.10, 11, 12

The benefits of physical activity (PA) for improving overall health status are widely recognized. Although it is well-known that PA can help to decrease all-cause mortality and risk factors of a wide variety of other chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, obesity, and musculoskeletal diseases,13, 14, 15, 16, 17 there is less evidence of the associations between PA and CBCs. Furthermore, even though clinical guidelines recommend that people with back pain should stay active,18 the nature of the activity is rarely described and may not necessarily always be a prescription to be physically active.

Many previous studies have focused on measuring the association of PA with nonspecific and radiating back pain. However, there are conflicting results reported in these studies. Although some studies found no association between chronic LBP and engaging in different intensities of PA,19,20 others reported that very low and very high levels of the PA (assessed by questionnaire) were associated with an increasing risk of chronic and radiating LBP (i.e., a U-shaped relationship).21, 22, 23 This apparent inconsistent relationship between PA and back pain described in previous studies may be due to the varying characteristics of PA (i.e., type, intensity, and duration). Moreover, a previous systematic review concluded that the incidence of LBP is associated with the nature and intensity of PA and suggested that the type, intensity, and duration of the activity should be considered in measuring the association with LBP.24 Furthermore, studies of older adults and those with multimorbidity are at particular risk of reverse causation, that is, the possibility that those with existing physical and medical comorbidities have a limited ability to engage in PA in the first place, and may have poorer health outcomes as a result of their chronic disease rather than their PA levels.25 To account for this, the association between PA and CBCs will be examined in those without existing comorbidities and in analyses stratified by age, sex, and body mass index (BMI).

A review of the existing literature on the association between PA and back pain cannot provide a clear understanding of this relationship. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to examine the association between PA and the prevalence of CBCs in a large representative population sample of adults in the UK. The secondary objective was to examine the association between type-specific volume of PA (walking, domestic, sport/exercise, cycling, football/rugby, running/jogging, manual work and housework) and prevalence of CBCs. The research hypothesis is that PA volume is inversely associated with the prevalence of CBCs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study is based on a cross-sectional survey comprising participants of the Health Survey for England (HSE; 1994, 1997–1999, 2003, 2004, 2006, and 2008) and Scottish Health Survey (SHS; 1995, 1998, and 2003). The surveys included adults aged ≥16 years. The HSE and SHS are household-based surveys that recruited a population sample with multistage, stratified probability sampling with postcode sectors selected at the first stage and household addresses selected at the second stage. The surveys have been described in detail elsewhere.26, 27 The current analyses included participants aged ≥16 years with valid data on all demographic, behavioral, and clinical variables of interest. All participants provided verbal informed consent before data collection. Ethics approvals for the various HSE and SHS surveys were granted by the North Thames Multicentre Research Ethics Committee for England, the Local Research Ethics Council in England, the Research Ethics Committee for all Area Health Boards in Scotland, and the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee for Scotland.

2.2. CBCs

Information on CBCs in the survey was collected from 2 questions assessing long-term conditions. First, participants were asked whether they had any long-standing illness, disability, or infirmity. If they replied positively, they were then asked to report up to 6 long-standing illnesses. We defined CBCs as responses coded as back problems/slipped disc/spine/neck, which were derived from responses indicating the presence of back trouble, lower back problems, back ache/curvature of spine/damage, fracture or injury to back, spine or neck/disc trouble/lumbago, inflammation of spinal joint/prolapsed intervertebral discs/Scheuermann's disease/spondylitis, spondylosis/worn discs in spine-affected legs. The responses were dichotomized into a yes/no variable, those who had CBCs and those who did not.

2.3. PA variables

The PA and Sedentary Behaviour Assessment Questionnaire was used to assess the frequency (number of days in the past 4 weeks) and duration (of an average episode) of participation in 4 domains of PA: (1) light (e.g., general tidying) and heavy (e.g., scrubbing floors) housework; (2) light and heavy manual work, gardening, and do-it-yourself activities; (3) walking; and (4) sport/exercise. Sport/exercise included cycling, running/jogging, swimming, ball sports, racquet sports, aerobics, dancing, and working out at a gym. The intensity of walking was determined by asking respondents whether their usual walking pace was slow/average (light intensity) or fairly brisk/fast (moderate intensity). Intensity of sport/exercise was determined by asking respondents whether the activity had made them out of breath or sweaty, and by the nature of the activity as indexed in the metabolic equivalent (MET) compendium.28 The PA and Sedentary Behaviour Assessment Questionnaire has demonstrated acceptable convergent validity when compared against accelerometry in assessment of moderate and vigorous intensity PA in a large validation study where Spearman's correlation coefficient was 0.38 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.32–0.45) in men and 0.40 (95%CI: 0.36–0.48) in women.29

Participation in PA was then calculated in MET hours per week by multiplying the volume of activity (Frequency × Duration) by the intensity of the activity in METs.29 Three PA variables were derived for the main analyses: MET hours per week of total PA, and min/week of moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA. Eight PA variables were derived for the secondary analyses: MET hours per week of walking, domestic PA (which consisted of housework as well as manual work, gardening and do-it-yourself activities), cycling, football/rugby, running/jogging, and sport/exercise excluding cycling, and minutes per week of manual work and housework activities. Because the PA and Sedentary Behaviour Assessment Questionnaire did not distinguish between recreational cycling and cycling for transport, we excluded cycling from the sport/exercise variable.

Total PA was categorized into groups framed around adherence to the current PA recommendations: (1) inactive (reporting no PA); (2) insufficiently active (reporting <7.5 MET h/week); (3) sufficiently active (reporting ≥7.5 and <15 MET h/week); and (4) very active (reporting ≥15 MET h/week).30

All other variables of PA were categorized into groups defined around tertiles: (a) none (defined as not participating in that type or level of activity), (b) low (defined as below the 25th percentile), (c) medium (defined as between the 25th and 75th percentiles), and (d) high (defined as above the 75th percentile). Previous studies have used this approach of categorization to distribute participants evenly into each category.31, 32, 33 Moderate-intensity PA was categorized into the following groups: (a) none (not reporting any moderate intensity activity), (b) low (reporting <90 min/week), (c) medium (reporting ≥90 and <150 min/week), and (d) high (reporting ≥150 and <300 min/week). We also included an additional group that reported ≥300 min/week to be in compliance with guidelines.34 Vigorous-intensity PA was categorized into the following groups: (a) none (not reporting any vigorous-intensity activity), (b) low (reporting <30 min/week), (c) medium (reporting ≥30 and <75 min/week), and (d) high (reporting ≥75 min/week). The categories for all other PA variables are displayed in Appendix Table 1.

2.4. Potential confounders

Potential confounders were identified a priori from a review of current literature.10, 11, 12 The following potential confounding variables were included in the analysis: age; sex; BMI underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2); smoking status (current smoker, nonsmoker, and previous smoker); ethnicity (white, black, Asian (non-Chinese), and Chinese or other); education (higher education, further education (A level), no further education (O level/below), other (foreign/full-time students), and no education qualification); social occupational class (professional and managerial, manual, nonmanual, and other (Armed Forces)); employment status (full time and part time); psychological distress (General Health Questionnaire-12: 0,1–3, and ≥4); cardiovascular disease; cancer; and musculoskeletal conditions (including arthritis/rheumatism/fibrositis and other problems of the bones/joints/muscles (not including CBCs)).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Multiple logistic regression analyses examined the association between PA and the prevalence of CBCs. The first model was adjusted for age and sex, and the second model was also adjusted for BMI, ethnicity, education level, smoking, social occupational class, psychological distress, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions, and was also mutually adjusted for the other PA types or intensity levels. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to exclude participants with cardiovascular disease (n = 13,893), cancer (n = 3545), and musculoskeletal conditions (n = 6876). Because no appreciable differences were found, these participants were retained in all the analyses.

We also stratified the analysis of MET hours per week of total PA by age (<65 years old and ≥65 years old), sex (male and female), and BMI (overweight (≥25 and <30 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2)). Considering that the total number of missing cases in each PA variable was <1% (except for moderate-intensity PA, which was 2.3%) of the total sample, participants with missing data were excluded from the analyses. Odds ratios (OR) with 95%CIs were calculated. All analyses were conducted from December 2016 to March 2017 using SPSS statistics (Version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For all statistical tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive characteristics

The general characteristics of the included participants are presented in Table 1. The analysis included 60,134 participants, of which 3336 (5.5%) reported CBCs. The mean age of the included participants was 45.7 ± 16.7 years and 50.6% were male, 85.2% were white, 39.0% were normal weight, 49.6% had never smoked, 27.5% had a higher education, 42.3% were manual workers, and 72.7% worked full time.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of participants recruited from the Health Survey of England (1994, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008) and Scottish Health Survey (1995, 1998, 2003).

| Characteristics | Chronic back condition |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 60,134) | Yes(n = 3336) | No(n = 56,798) | |

| n (%) | % | % | |

| Age (year)a | 45.7 ± 16.7 | 49.5 ± 14.0 | 45.5 ± 16.8 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 28,047 (50.6) | 6.0 | 94.0 |

| Female | 32,087 (49.4) | 5.1 | 94.9 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 51,604 (85.2) | 6.2 | 93.8 |

| Black | 2477 (4.3) | 1.5 | 98.5 |

| Asian | 4425 (7.7) | 1.6 | 98.4 |

| Chinese or other | 1628 (2.8) | 2.1 | 97.9 |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 898 (1.5) | 2.7 | 97.3 |

| Normal | 23,467 (39.0) | 4.7 | 95.3 |

| Overweight | 23,037 (38.3) | 5.9 | 94.1 |

| Obese | 12,732 (21.2) | 6.7 | 93.3 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 29,820 (49.6) | 4.6 | 95.4 |

| Previous smoker | 14,200 (23.6) | 6.7 | 93.3 |

| Current smoker | 16,114 (26.8) | 6.3 | 93.7 |

| Education | |||

| Higher education | 16,560 (27.5) | 5.0 | 95.0 |

| Further education (A level) | 6370 (10.6) | 4.8 | 95.2 |

| No further education (O level/below) | 16,449 (27.4) | 5.8 | 94.2 |

| Other (foreign/full-time students) | 5533 (9.2) | 4.5 | 95.5 |

| No qualification | 15,222 (25.3) | 6.5 | 93.5 |

| Social occupational class | |||

| Professional and managerial | 19,692 (32.7) | 5.3 | 94.7 |

| Manual | 25,408 (42.3) | 6.1 | 93.9 |

| Nonmanual | 14,685 (24.4) | 4.9 | 95.1 |

| Other (Armed Forces) | 349 (0.6) | 5.2 | 94.8 |

| Employment status | |||

| Full time | 43,712 (72.7) | 5.7 | 94.3 |

| Part time | 16,422 (27.3) | 5.0 | 95.0 |

| GHQ-12 score | |||

| 0 | 49,628 (61.4) | 4.2 | 95.8 |

| 1–3 | 19,751 (24.4) | 6.9 | 93.1 |

| ≥4 | 11,451 (14.2) | 9.3 | 90.7 |

| Prevalent cardiovascular disease | |||

| Yes | 13,893 (23.1) | 6.5 | 93.5 |

| No | 46,241 (76.9) | 5.3 | 94.7 |

| Prevalent cancer | |||

| Yes | 3545 (5.9) | 11.3 | 88.7 |

| No | 56,589 (94.1) | 5.2 | 94.8 |

| Prevalent musculoskeletal conditions | |||

| Yes | 6876 (11.4) | 10.7 | 89.3 |

| No | 53,258 (88.6) | 4.9 | 95.1 |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; GHQ-12 = General Health Questionnaire-12.

Data are presented mean ± SD.

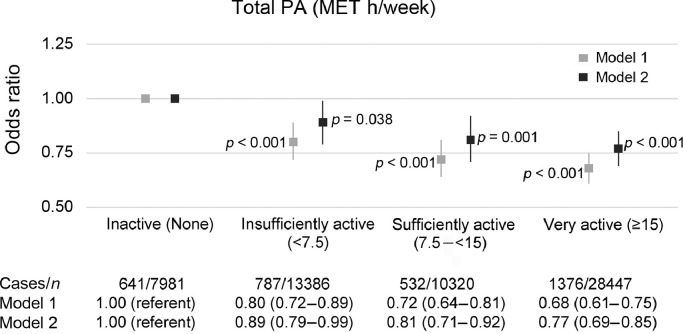

3.2. Association between total PA volume and prevalence of CBCs

There was an inverse relationship between total PA volume and CBCs (Fig. 1). The fully adjusted OR was 0.89 (95%CI: 0.79–0.99) for insufficiently active, 0.81 (95%CI: 0.71–0.92) for sufficiently active, and 0.77 (95%CI: 0.69–0.85) for very active people, compared with those who were not active. We re-analyzed our data after excluding participants with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions, but no appreciable differences were found in the results (Appendix Tables 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Logistic regression for describing the association between total PA volume and prevalence of chronic back conditions. Model 1 is adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 is also adjusted for ethnicity, body mass index, smoking, education, occupation, employment status, psychological distress, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions (including arthritis/rheumatism/fibrositis and other problems of the bones/joints/muscles). Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant at the level of p < 0.05. MET = metabolic equivalent; PA = physical activity.

In the stratified analysis by age, we found an inverse association between total PA and CBCs in participants <65 years old (Appendix Table 4). The fully adjusted OR was 0.71 (95%CI: 0.63–0.81) for insufficiently active, 0.66 (95%CI: 0.58–0.76) for sufficiently active, and 0.60 (95%CI: 0.53–0.67) for very active participants, compared with those who were not active. However, we found no association between total PA and CBCs in participants aged ≥65 years.

Compared with male participants who were not active, male participants who were sufficiently and very active had a lower prevalence of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 0.82 (95%CI: 0.68–0.98) and OR = 0.77 (95%CI: 0.66–0.89), respectively; Appendix Table 5). We also found an inverse association between total PA and CBCs in female participants. The fully adjusted OR was 0.85 (95%CI: 0.72–1.00) for insufficiently active females, 0.80 (95%CI: 0.67–0.96) for sufficiently active females, and 0.77 (95%CI: 0.65–0.90) for very active females, compared with female participants who were not active.

Compared with overweight participants who were inactive, overweight participants who were very active had a lower odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 0.77 (95%CI: 0.65–0.92); Appendix Table 6). We also found that obese participants who were sufficiently and very active had lower odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 0.64 (95%CI: 0.50–0.82) and 0.67 (95%CI: 0.55–0.83), respectively), compared with obese participants who were inactive.

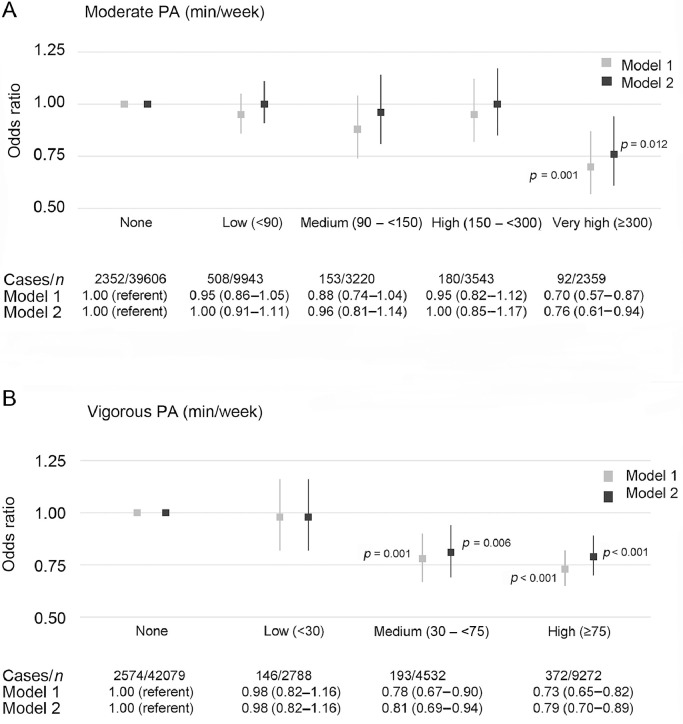

3.3. Moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA

A very high level of moderate-intensity activity was associated with a lower odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 0.76 (95%CI: 0.61–0.94)) compared with those who did not engage in any activity of moderate intensity (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Logistic regression for describing association between PA of moderate- and vigorous-intensity and prevalence of chronic back conditions. Model 1 is adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 is also adjusted for ethnicity, body mass index, smoking, education, occupation, employment status, psychological distress, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions (including arthritis/rheumatism/fibrositis and other problems of the bones/joints/muscles) and all other PA levels (moderate and vigorous PA, mutually). Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant at the level of p < 0.05. PA = physical activity.

Vigorous intensity PA was inversely associated with CBCs (Fig. 2B). The fully adjusted OR for a medium level of vigorous-intensity PA was 0.81 (95%CI: 0.69–0.94), and for a high level of vigorous-intensity PA it was 0.79 (95%CI: 0.70–0.89) compared with those who did not engage in any vigorous-intensity activities.

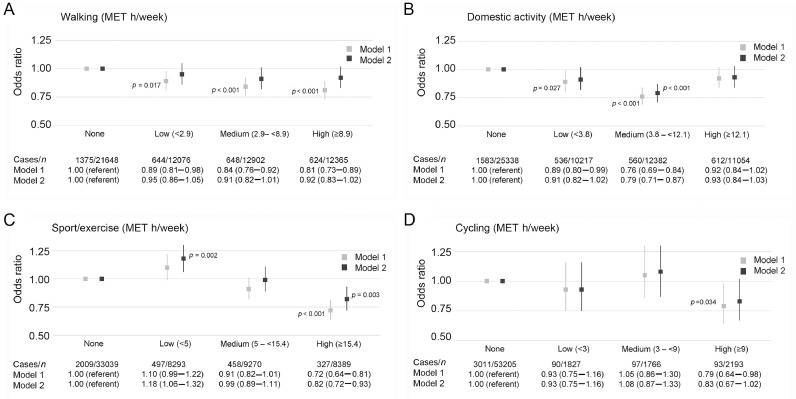

3.4. Walking

Walking was inversely associated with the prevalence of CBCs when the analysis was adjusted for age and sex only (the OR was 0.89 (95%CI: 0.81–0.98) for a low level, 0.84 (95%CI: 0.76–0.92) for a medium level, and 0.81 (95%CI: 0.73–0.89) for a high level), compared with those who did not walk (Fig. 3A). However, these associations did not persist in the fully adjusted model.

Fig. 3.

Logistic regression for describing association between different types of PA (A, walking; B, domestic activity; C, sport/exercise; and D, cycling) and prevalence of chronic back conditions. Model 1 is adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 is also adjusted for ethnicity, body mass index, smoking, education, occupation, employment status, psychological distress, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions (including arthritis/rheumatism/fibrositis and other problems of the bones/joints/muscles) and mutually adjusted for all other PA types (walking, domestic, sport/exercise, and cycling). Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant at the level of p < 0.05. MET = metabolic equivalent; PA = physical activity.

3.5. Domestic activity

Medium-level domestic activity was associated with lower odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 0.79 (95%CI: 0.71–0.87)) compared with those who were not engaged in any domestic activity (Fig. 3B).

3.6. Sport/exercise

Sport/exercise was associated with CBCs in a less consistent manner (Fig. 3C). A high level of sport/exercise showed a lower odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 0.82 (95%CI: 0.72–0.93)). Conversely, a low level of sport/exercise showed significantly higher odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 1.18 (95%CI: 1.06–1.32)).

3.7. Cycling

Cycling was associated with a lower odds of CBCs in the age- and sex-adjusted model (OR for high level = 0.79 (95%CI: 0.64–0.98); Fig. 3D). However, no association was found following adjustment for potential confounders (fully adjusted OR = 0.83 (95%CI: 0.67–1.02)).

3.8. Football/rugby and running/jogging

Participation in football/rugby or running/jogging was inversely associated with CBCs (Appendix Table 7). The fully adjusted OR for participation in football/rugby was 0.67 (95%CI: 0.55–0.83) compared with those who did not participate in any football/rugby. The fully adjusted OR for participation in running/jogging was 0.67 (95%CI: 0.55–0.81) compared with those who did not participate in any running/jogging.

3.9. Manual work and housework activities

A high level of manual work was associated with higher odds of CBCs (fully adjusted OR = 1.22 (95%CI: 1.00–1.48)) compared with those who did not engage any manual work activity (Appendix Table 8). Housework was associated with lower odds of CBCs in the age- and sex-adjusted model (OR for a medium level = 0.82 (95%CI: 0.71–0.95) and OR for a high level = 0.83 (95%CI: 0.71–0.96)), but these associations did not persist in the fully adjusted model (Appendix Table 8).

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine the association between total and type-specific volume of PA and the prevalence of CBCs. We found an inverse association between total PA volume and the prevalence of CBCs. In general, adhering to the current PA recommendations was associated with approximately a 20% lower odds of reporting a CBC compared with those who were inactive. The results also showed that the reductions in CBCs of the greatest magnitude were observed in participants who were very active. Interestingly, participants who were insufficiently active (i.e., <7.5 MET h/week of total PA) still had a significantly lower prevalence of CBCs (11%).

Stratified analyses according to age, sex, and BMI showed a different trend. Several different patterns were observed in the groups, which suggest that specific groups might be better managed with PA modification. Overweight participants who were very active showed approximately a 23% lower odds of reporting CBCs, whereas obese participants who were sufficiently or very active showed approximately a 35% lower odds of reporting CBCs. There was also an inverse association between total PA and CBCs in participants <65 years old, but no association was found in those aged ≥65 years. Among male or female participants, the lower odds of CBCs (23%) were seen in those who were very active.

Multiple health guidelines30, 34 recommend increasing moderate-intensity PA over the minimum recommended level of 150 min/week to gain greater health benefits. In our study, only those achieving ≥300 min/week of moderate-intensity PA were associated with a lower prevalence of CBCs compared with those who did not engage in any moderate-intensity PA, suggesting a potential threshold effect. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel finding that merits attention. Future prospective studies should investigate the possibility of a threshold effect for potentially beneficial associations between CBCs and levels of PA that are higher than the recommended minimum.

We also found that engaging in ≥30 min/week of vigorous-intensity PA was associated with lower odds of reporting CBCs. Furthermore, engaging in ≥75 min/week in vigorous-intensity PA was associated with 21% lower odds in reporting CBCs. These results concur with a previous prospective cohort study,35 which found a significant association between increasing frequency of vigorous-intensity PA and decreasing prevalence of LBP in elderly people.

Despite the potential health benefits of walking, few studies have investigated its association with CBCs. Our study demonstrated that participating in any level of walking was associated with a lower odds of CBCs, compared with those who did not walk, only after adjusting for age and sex; and subjects who reported >8.9 MET h/week of walking were less likely to have CBCs than those who did not walk. A previous study has shown similar results in men, where walking for ≥150 min/week was associated with lower odds of LBP only after adjusting for age and BMI.22

Medium domestic activity was associated with a decreased odds of CBCs. However, when we investigated the association of manual work and housework separately with CBCs, we found that a high level of manual work was associated with higher odds of CBCs, whereas low and medium levels of manual work and any level of housework were not associated with CBCs. The existing evidence investigating the association between domestic activity and back conditions is scant.24 However, longitudinal data from the Canadian National Population Health Survey (1994–1997) demonstrated an inverse association between gardening/yard work and back pain in men.36 In contrast, Huebscher et al.37 found that heavy domestic activity (defined as being engaged in ≥2 h/week in vigorous gardening/yard work) was associated with an increased odds of having LBP. The results of these earlier studies may not be directly comparable with our study because we defined medium domestic activity as being engaged in >3.8 but <12.1 MET h/week of housework activities, manual work activities, gardening, and do-it-yourself activities. Therefore, a possible explanation for the inconsistencies between these studies is due to the differences in the definitions and classifications of domestic activities. Another explanation may be due to the small sample size included in the study by Huebscher et al.,37 compared with our much larger sample size. Our sample size is more likely to have adequate variability in exposure and thus is more likely to detect associations when those exist.

In our study, sport/exercise included a wide range of exercises and noncompetitive sport. We found that participation in high-level sport/exercise (≥15.4 MET h/week) was inversely associated with the presence of CBCs. Several cross-sectional studies have found an association between engaging in sport/exercise and prevalence of LBP. For example, Heneweer et al.21 found that participation in sports was associated with a decreased odds of having chronic LBP. This finding was consistent with a 10-year prospective study that reported that participating in sport/exercise for ≥1 h/week was associated with a lower risk of chronic LBP.38 Conversely, low levels of sport/exercise (<5 MET h/week) were associated with higher odds of CBCs. This finding is in accordance with a previous cohort study of the general population conducted in Norway, which demonstrated that people who engage in physical exercise <1 session per week (20 min/week) are more likely to develop LBP.39 Therefore, based on these consistent results, sport/exercise could be recommended for the prevention or management of LBP.

Participation in football/rugby or running/jogging was associated with lower odds of CBCs in our study. High-level cycling (≥9 MET h/week) was associated with a lower odds of CBCs only after adjusting for age and sex. However, there are not many studies investigating the association of other specific types of activities, such as tennis and squash. Therefore, future studies should examine the associations between specific types of sport/exercise and back pain. They might also consider categorizing these types of activities into groups based on their loading on the back.21, 40

Our results highlight the importance of determining the frequency, duration, intensity, and type of PA appropriate for the prevention or management of CBCs. However, the differing methods used in previous studies regarding the description and categorization of PA make a direct comparison between our study and previous work difficult. Moreover, our results highlight the importance of adjusting the statistical analysis for other PA types or levels that may be significantly associated with CBCs. These 2 important differences in methodology—categorizing PA and adjusting for other PA types or levels—may also explain some of the inconsistency between our findings and those of previous studies.

One strength of our study is that it included a large, pooled sample comprising a series of nationally representative samples of the populations from England and Scotland. The large population sample used in our analyses, which is more likely to have adequate variability in the exposure, made it more likely that we detected associations when those existed. Another important advantage of this very large sample size was that it allowed for stratified analyses by age, sex, and BMI in the association between total PA and CBCs. An additional strength of the study was that it adjusted for some comorbid factors (cardiovascular disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal conditions), which may have confounded the association of PA with CBCs.

There are some limitations to this study that should be considered. Only 5% of the sample reported having a CBC, which is lower than other prevalence estimates of LBP in British populations.4, 5, 6 This finding may be attributed to the structure of the survey questions used to identify CBCs, in which participants were only questioned about CBCs if they first reported having a long-standing illness, disability, or infirmity. Owing to the cross-sectional design of this study, the relationships identified might be susceptible to the possibility of reverse causality (i.e., CBCs lead to reducing the activity level).41 Another major limitation is the use of a self-reported PA questionnaire that might be subject to recall bias, which could result in an underestimation or overestimation of the activity level.42 However, this limitation may be mitigated to some degree by the acceptable convergent validity demonstrated by the questionnaire when compared with accelerometry in assessment of moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA in a representative sample. The final limitation that should be mentioned is the lack of control for occupational PA because of the limited availability of occupational PA data in the survey. However, we were able to adjust for social occupational class, which may be considered a proxy for occupational PA and may, therefore, account for the potential influence of the occupational PA on the association between PA and CBCs.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study showed that total PA was inversely associated with CBCs. Moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities were associated with low odds of CBCs. In addition, medium domestic activity and participation in football/rugby or running/jogging were also inversely associated with CBCs. However, PA resulting from high-level manual work was associated with higher odds of CBCs. Sport/exercise was associated with CBCs in a less consistent manner; high-level sport/exercise was associated with low odds of CBCs, and low-level sport/exercise was associated with high odds of CBCs. Further research that includes a randomized clinical trial or that incorporates a longitudinal design with an inception cohort without LBP is required to confirm our results.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The Health Survey for England was funded by the English Department of Health/Health and Social Care Information Centre. The Scottish Health Survey was funded by the Scottish Executive. These funders had no role in the present study. The data presented here are available from the UK Data Archive (http://www.data-archive.ac.uk/findingData/hseTitles.asp). This research did not receive any specific grant support from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. However, HA is supported by a Ph.D. scholarship from Taif University in Taif, Saudi Arabia. ES is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council through a Senior Research Fellowship.

Author's contributions

HA developed the study protocol, performed the statistical analyses under supervision of ES, had partial access to the data and took responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the results, drafted and revised the article, and contributed to the interpretation of the results; DS developed the study protocol, contributed to the interpretation of the results and revision of the article; SWMC performed the statistical analyses under supervision of ES, had partial access to the data and took responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the results; MM developed the study protocol, contributed to the interpretation of the results and revision of the article; ES developed the study protocol, assisted with the analysis and provided statistical expertise, had full access to the data and took responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the results, contributed to the interpretation of the results and revision of the article. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2019.01.003.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hoy D., Bain C., Williams G., March L., Brooks P., Blyth F. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2028–2037. doi: 10.1002/art.34347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T., Abajobir A.A., Abate K.H., Abbafati C., Abbas K.M., Abd-Allah F. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker B.F. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:205–217. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillman M., Wright A., Rajaratnam G., Tennant A., Chamberlain M.A. Prevalence of low back pain in the community: implications for service provision in Bradford, UK. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:347–352. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh K., Cruddas M., Coggon D. Low back pain in eight areas of Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:227–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinnon M.E., Vickers M.R., Ruddock V.M., Townsend J., Meade T.W. Community studies of the health service implications of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:2161–2166. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199709150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fayaz A., Croft P., Langford R.M., Donaldson L.J., Jones G.T. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoy D., Brooks P., Blyth F., Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krismer M., van Tulder M. Low back pain (non-specific) Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Tulder M., Koes B., Bombardier C. Low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:761–775. doi: 10.1053/berh.2002.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valat J.P. Factors involved in progression to chronicity of mechanical low back pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:193–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoy D., Brooks P., Blyth F., Buchbinder R. The Epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Physical activity: exercise referral schemes. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph54 Available at: 2014. [accessed 04.05.2017]

- 14.O'Donovan G., Lee I.M., Hamer M., Stamatakis E. Association of “weekend warrior” and other leisure time physical activity patterns with risks for all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:335–342. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamer M., Ingle L., Carroll S., Stamatakis E. Physical activity and cardiovascular mortality risk: possible protective mechanisms? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:84–88. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182251077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadarangani K.P., Hamer M., Mindell J.S., Coombs N.A., Stamatakis E. Physical activity and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in diabetic adults from Great Britain: pooled analysis of 10 population-based cohorts. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1016–1023. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warburton D.E., Glendhill N., Quinney A. The effects of changes in musculoskeletal fitness on health. Can J Appl Physiol. 2001;26:161–216. doi: 10.1139/h01-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koes B.W., van Tulder M., Lin C.W., Macedo L.G., McAuley J., Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–2094. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamada M., Kitayuguchi J., Lee I.M., Hamano T., Imamura F., Inoue S. Relationship between physical activity and chronic musculoskeletal pain among community-dwelling Japanese adults. J Epidemiol. 2014;24:474–483. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heuch I., Heuch I., Hagen K., Zwart J.A. Is there a U-shaped relationship between physical activity in leisure time and risk of chronic low back pain? A follow-up in the HUNT Study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:306. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2970-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heneweer H., Vanhees L., Picavet H.S.J. Physical activity and low back pain: a U-shaped relation? Pain. 2009;143:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim W., Jin Y.S., Lee C.S., Hwang C.J., Lee S.Y., Chung S.G. Relationship between the type and amount of physical activity and low back pain in Koreans aged 50 years and older. PM R. 2014;6:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiri R., Solovieva S., Husgafvel-Pursiainen K., Telama R., Yang X., Viikari J. The role of obesity and physical activity in non-specific and radiating low back pain: the Young Finns study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:640–650. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heneweer H., Staes F., Aufdemkampe G., Van Rijn M., Vanhees L. Physical activity and low back pain: a systematic review of recent literature. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:826–845. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1680-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slater M., Perruccio A.V., Badley E.M. Musculoskeletal comorbidities in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease: the impact on activity limitations; a representative population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mindell J., Biddulph J.P., Hirani V., Stamatakis E., Craig R., Nunn S. Cohort profile: the health survey for England. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray L., Batty G.D., Craig P., Stewart C., Whyte B., Finlayson A. Cohort profile: the Scottish health surveys cohort: linkage of study participants to routinely collected records for mortality, hospital discharge, cancer and offspring birth characteristics in three nationwide studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:345–350. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ainsworth B.E., Haskell W.L., Herrmann S.D., Meckes N., Bassett D.R., Jr, Tudor-Locke C. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scholes S., Coombs N., Pedisic Z., Mindell J.S., Bauman A., Rowlands A.V. Age- and sex-specific criterion validity of the Health Survey for England physical activity and sedentary behavior assessment questionnaire as compared with accelerometry. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:1493–1502. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. 2008. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines Available at: 2008. [accessed 20.06.2018]

- 31.Wahid A., Manek N., Nichols M., Kelly P., Foster C., Webster P. Quantifying the association between physical activity and cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stamatakis E., Hamer M., Lawlor D.A. Physical activity, mortality, and cardiovascular disease: is domestic physical activity beneficial? The Scottish Health Survey—1995, 1998, and 2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1191–1200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blair S.N., Cheng Y., Holder J.S. Is physical activity or physical fitness more important in defining health benefits? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(Suppl. 6):S379–S399. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Health Australia's Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines. 2014. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines Available at: 2014. [accessed 17.05.2017]

- 35.Hartvigsen J., Christensen K. Active lifestyle protects against incident low back pain in seniors: a population-based 2-year prospective study of 1387 Danish twins aged 70–100 years. Spine. 2007;32:76–81. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250292.18121.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kopec J.A., Sayre E.C., Esdaile J.M. Predictors of back pain in a general population cohort. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:70–77. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000103942.81227.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huebscher M., Ferreira M.L., Junqueira D.R.G., Refshauge K.M., Maher C.G., Hopper J.L. Heavy domestic, but not recreational, physical activity is associated with low back pain: Australian Twin low BACK pain (AUTBACK) study. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:2083–2089. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsen T.I.L., Holtermann A., Mork P.J. Physical exercise, body mass index, and risk of chronic pain in the low back and neck/shoulders: longitudinal data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:267–273. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksen W., Natvig B., Bruusgaard D. Smoking, heavy physical work and low back pain: a four-year prospective study. Occup Med (Lond) 1999;49:155–160. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mogensen A.M., Gausel A.M., Wedderkopp N., Kjaer P., Leboeuf-Yde C. Is active participation in specific sport activities linked with back pain? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17:680–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel K.V., Dansie E.J., Turk D.C. Impact of chronic musculoskeletal pain on objectively measured daily physical activity: a review of current findings. Pain Manag. 2013;3:467–474. doi: 10.2217/pmt.13.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kremer E.F., Block A., Gaylor M.S. Behavioral approaches to treatment of chronic pain: the inaccuracy of patient self-report measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1981;62:188–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.