Abstract

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a circulating lipoprotein, and its level is largely determined by variation in the Lp(a) gene (LPA) locus encoding apo(a). Genetic variation in the LPA gene that increases Lp(a) level also increases coronary artery disease (CAD) risk, suggesting that Lp(a) is a causal factor for CAD risk. Lp(a) is the preferential lipoprotein carrier for oxidized phospholipids (OxPL), a proatherogenic and proinflammatory biomarker. Lp(a) adversely affects endothelial function, inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrinolysis, and plaque stability, leading to accelerated atherothrombosis and premature CAD. The INTER-HEART Study has established the usefulness of Lp(a) in assessing the risk of acute myocardial infarction in ethnically diverse populations with South Asians having the highest risk and population attributable risk. The 2018 Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guideline have recognized elevated Lp(a) as an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk enhancer for initiating or intensifying statin therapy.

Keywords: Lipoprotein(a), Oxidized phospholipids, Genetic risk factor, Indians, Acute myocardial infarction, Premature coronary artery disease, Cardiovascular disease, Kringles, Isoforms, Mendelian randomization, Single nucleotide polymorphism, Genome-wide association studies, meta-analysis

Abbreviations: ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; apo(a), apolipoprotein(a); ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAVD, calcific aortic valve disease; CNV, copy number variation; GRS, genetic risk score; GWAS, Genome-Wide Association Studies; HMW, high molecular weight; KIV-2, kringle IV type-2 repeats; LMW, low molecular weight; LPA, Lp(a) gene; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); MACE, major acute cardiovascular events; MR, Mendelian randomization; NHLBI, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; OR, odds ratio; OxPL, oxidized phospholipids; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism

1. Introduction

Elevated Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], also called hyperlipoproteinemia(a), is a highly prevalent genetic risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). According to the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) report published in 2018, an estimated 1.4 billion people globally have Lp(a) levels ≥ 50 mg/with a prevalence ranging from 10% to 30% and possibly higher in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), or chronic kidney disease (CKD).1, 2 Importantly, elevated Lp(a) levels can occur in patients with otherwise normal lipid levels. Genetic, epidemiologic, and pathophysiologic studies show Lp(a) is a causal factor for coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), CAVD, and heart failure.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 This increased risk caused by elevated Lp(a) has not yet gained recognition by practicing physicians.

In 1963, geneticist Kare Berg10 discovered a new antigen (in human sera) associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and named it Lp(a), in accordance with the prevailing nomenclature of antigens in immunogenetics. The milestones pertinent to research advances regarding Lp(a) over the past decades are listed in Table 1.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 By the 1980s, it became clear that Lp(a) is a genetic trait seen in 25–30% of people of European descent (based on the prevalence of small Lp(a) isoforms that are associated with higher Lp(a) levels).12, 13 Kamstrup et al14 demonstrated an increased risk of atherosclerotic stenosis in the coronary, carotid, and femoral arteries as a function of genetically elevated Lp(a) levels. Mendelian randomization (MR) studies have demonstrated a linear dose–response relationship for variations of LPA gene to both increased level of Lp(a) and an increased risk of CAD (Table 2).1, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25

Table 1.

Milestones in establishing Lp(a) as a risk factor for ASCVD (Refs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

| 1 | Kare Berg discovers a new antigen in human sera associated with LDL-C and names it Lp(a) in accordance with prevailing nomenclature for antigen patterns in immunogenetics. |

| 2 | Lp(a) is found to be a highly prevalent genetic trait with high levels observed in 20–30% of the population of European descent. |

| 3 | Lp(a) levels are relatively independent of age and gender and vary 1000-fold among individuals (including siblings). Diet and nutritional factors have minimal influence on Lp(a) levels. |

| 4 | Lp(a) is found to be the preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids—a novel proatherogenic and proinflammatory biomarker implicated in destabilizing vulnerable coronary plaques, resulting in ACS. |

| 5 | Epidemiological and case-control studies show elevated Lp(a) to be an independent ASCVD risk factor with a 2-fold risk (seeTable 2for ASCVD risk in genetic studies). |

| 6 | Three studies from PHS found no association between elevated Lp(a) and AMI, stroke, or PAD, and temporarily dampened Lp(a) research. This failure to find an association was later ascribed to the use of stored sera and importantly to the use of an assay that was sensitive to Lp(a) isoforms. |

| 7 | Marcovina et al develop and validate an isoform-insensitive ELISA that becomes the reference standard for measuring Lp(a) levels. A fourth report from PHS using this assay ELISA and fresh serum find strong correlation of elevated to CAD, reviving interest on Lp(a) research. |

| 8 | Numerous studies using fresh serum and using isoform-insensitive ELISA find consistent association of elevated Lp(a) with CAD and other forms of CVD. |

| 9 | Several studies using fresh serum and genetic studies show that ASCVD risk begins at Lp(a) levels ≥20 mg/dl. |

| 10 | European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel chose a threshold of Lp(a) at ≥ 50 mg/dl, whereas NHLBI-WG chose Lp(a) ≥30–50 mg/dl as the atherothrombotic range. |

| 11 | The INTERHEART Lp(a) study in people of seven largest ethnicities demonstrates wide interethnic differences in Lp(a) levels and on the AMI risk conferred by elevated Lp(a). |

| 12 | Lipoprotein apheresis, on top of maximally tolerated statin therapy, can substantially lower ASCVD risk (up to 85%) as well as regress coronary atherosclerosis. |

| 13 | The NHLBI-WG reports that 1.4 billion people have elevated Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl including 469 million South Asians. |

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; AMI = acute myocardial infarction; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAD = coronary artery disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; Lp(a) = lipoprotein(a); LDL-C = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; NHLBI-WG = National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Working Group; PAD = peripheral arterial disease; PHS= Physician's Health Study; ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Table 2.

Chronology of major genetic and Mendelian randomization studies on the role of Lp(a) in CAD and other conditions (Ref 1, 2, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25).

| Author | Year | Major findings |

|---|---|---|

| Sandholzer, C15 | 1992 | Lp(a) levels are largely determined by alleles at the LPA gene locus. Small apo(a) isoforms associated with high Lp(a) plasma concentrations were more frequent in CAD patients. |

| Kamstrup, P.R16 | 2009 | Genetically elevated Lp(a) was associated with 22% increase in MI per doubling of Lp(a) level. |

| Clarke, R17 | 2009 | Two SNPs (rs3798220 and rs10455872) at the LPA locus are strongly and independently related to Lp(a) levels and to CAD risk. |

| Chassman D. I.18 | 2009 | In Women's Health Study, carriers of an LPA SNP (rs3798220) had elevated Lp(a) and double the CVD risk. Aspirin reduced the risk by 56% in carriers but not in non-carriers. |

| Hopewell, J.C19 | 2011 | In the Heart Protection Study, the LPA SNPs (rs3798220 and rs10455872) were examined together as an LPA genotype risk score (LPAGRS). The LPAGRS was strongly associated with CAD and PAD. |

| Helgadottir, A.20 | 2012 | The two LPAGRS was associated with CAD, MI, stroke, PAD, and abdominal aortic aneurysm. This study indicates the association of Lp(a) with atherosclerotic burden. |

| Thanassoulis, G21 | 2013 | Expanded the phenotypic characterization of Lp(a) levels mediated by genetic variation in the LPA locus with incident aortic-valve calcification and CAVD across multiple ethnic groups |

| Kamstrup, P. R22 | 2014 | Elevated Lp(a) levels and corresponding genotypes were associated with increased risk of CAVD in the general population, with levels >90 mg/dl predicting a threefold increased risk. |

| Laschkolnig, A23 | 2014 | Expanded the phenotypic characterization of elevated Lp(a) concentrations, from small isoforms and rs10455872 with PAD. |

| Thanassoulis, G24 | 2016 | Using a MR study design, the strong association of elevated Lp(a) concentrations resulting from genetic variants in LPA with CAVD was confirmed. |

| Emdin, C.A.25 | 2016 | The phenotypes characterization associated with elevated Lp(a) expanded to include CAD, AMI, CAVD, stroke, and heart failure. |

| Kronenberg, F12 | 2016 | The apo(a) size polymorphism results in >40 isoforms, which are determined at the time of conception. Small Lp(a) isoforms (up to 22 KIV-2 repeats) have higher Lp(a) levels and higher CAD risk independent of established risk factors. Large isoforms in general are not associated with elevated Lp(a) or CAD. |

| Tsimikas, S.1, 2 | 2017 | MR studies demonstrate a 3–4-fold higher CAD risk in those with elevated Lp(a) compared with people with low Lp(a) levels; given the former capture the effects of lifelong exposure and are generally devoid of confounding factors, MR studies provide the most accurate risk estimates. |

AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CAD = coronary artery disease; CAVD = calcific aortic valve disease; LPA = lipoprotein(a) gene MI = myocardial infarction; MR = Mendelian randomization; OR = odds ratio; PAD = peripheral arterial disease SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Analysis of pooled data involving 126,634 participants in 36 prospective studies (1970–2009) demonstrated a log––linear relationship of Lp(a) levels to acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke.26 During 1.3 million person-years of follow-up, 22,076 first-ever major acute cardiovascular events (MACEs) occurred, including 9336 CAD events, 1903 ischemic strokes, and 338 hemorrhagic strokes.26 Data confirm that the relationship of Lp(a) level to elevated CAD risk is log–linear with risk beginning at ≥20–30 mg/dl and accelerating log linearly with level ≥50 mg/dl.1, 9, 16, 26, 27, 28 The INTERHEART-Lp(a) study has shown that elevated Lp(a) concentration, and the risk conferred by elevated Lp(a) vary significantly by ethnicity.11

With this backdrop, we examine the role of Lp(a) in detail, including pathophysiological aspects, Lp(a) gene (LPA) and structure, issues related to measurement, assay methods, and reporting of Lp(a) level and its management. We provide evidenced-based justification to consider Lp(a) as a genetic, independent, and causal factor, comparable to the nine modifiable INTERHEART risk factors for CVD.29

2. Lp(a) structure, levels, and pathophysiological perspectives

2.1. Lp(a) gene and apo(a)

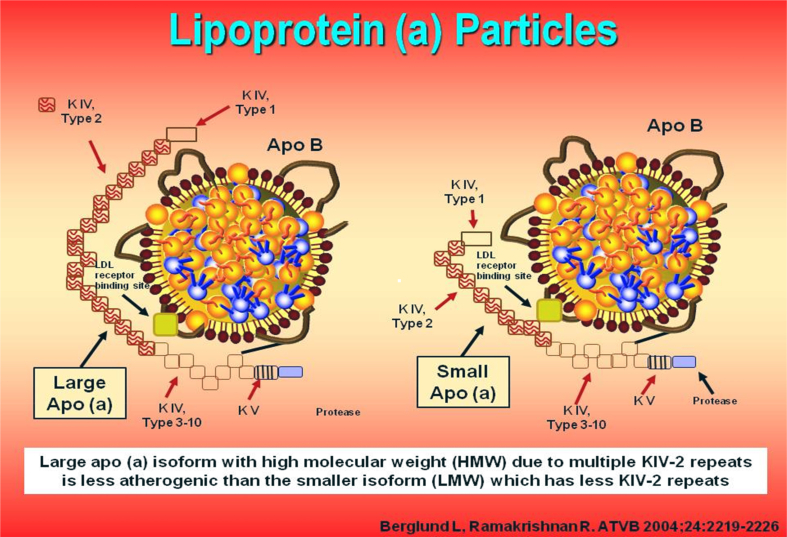

LPA located on chromosome 6q26-q27 is the major gene locus for Lp(a) concentrations in all populations.12 Cloning and sequencing of LPA reveal an extensive structural homology with plasminogen gene.8, 30 The gene structure and a Lp(a) particle model are depicted in Fig. 1.31 Plasminogen contains five kringles (K1 to K5) (1 copy each of KI to KV) and an active protease domain. Apolipoprotein(a), the pathognomonic component of Lp(a), is derived from kringle IV (KIV) and KV and the protease domain of plasminogen30, 31, 32, 33; it does not contain KI, KII, and KIII. Apo(a) contains 10 subtypes of KIV repeats, composed of 1 copy each of KIV1, KIV3−10, KV, and multiple copies of KIV2, which ranges from 1 to >40 copies (Fig. 1).31 Lp(a) downregulates endothelial cell plasmin generation and adversely modulate the delicate balance between thrombus formation and fibrinolysis.12 The homology with plasminogen drives the atherogenicity and thrombogenicity of Lp(a).2 LPA gene is one of the strongest monogenic risk factors for CAD.2 The LPA gene is highly expressed in liver with dramatic decrease as well as increase in Lp(a) observed after liver transplant.34, 35

Fig. 1.

Lp(a) particles: One containing large apo(a) isoform and the other containg small apo(a) isoform.

2.2. Lp(a) particle

Lp(a) particle is formed by the covalent binding of apo(a) to apolipoprotein B of an LDL particle.36 The apo(a) protein is large (larger than apo B) with a molecular mass of 200–900 KD.2 Apo (a) is highly polymorphic in size because of the number of kringle IV type 2 repeats (KIV-2)–encoding sequences resulting in >40 isoforms and thus >40 different sizes of Lp(a) particles.31 Lp(a) is more atherogenic than LDL on a molar basis because the former contains all the atherogenic components of LDL plus apo(a).1, 2 Lp(a) has a longer plasma residence time than LDL. The physiological role of Lp(a) is not fully elucidated, but the postulates include provision of cholesterol for cell proliferation during repair and reduction of risk for increased bleeding, especially during childbirth, through inhibition of fibrinolysis.2, 9

2.3. Lp(a) levels

Circulating Lp(a) level is primarily determined by the LPA gene encoding apo(a) (accounting for >90% of the variance) and is not significantly influenced by age, sex, physical activity, diet, and nutrition.1 Lp(a) concentrations vary 4-fold among people of various ethnicities and 1000-fold between individuals (from less than 0.1 mg/dL to as high as 387 mg/dL), with a skewed distribution in most populations.9, 12, 37 The impact of LPA variations on CAD risk is directly proportional to its effect on circulating Lp(a) levels.

2.4. KIV-type 2 copy number variation- and Lp(a) levels

Apo(a) size polymorphism [KIV-type 2 copy number variation (KIV-2 CNV)] is a major determinant of Lp(a) levels and explains 20–80% of the variance in Lp(a) levels.12, 36 The KIV-2 CNV in the LPA gene is transcribed into mRNA and translated into the apo(a) proteins of different sizes.38 More than 80% of all individuals carry two different-sized apo(a) isoforms, each inherited from one parent. Smaller apo(a) isoform up to and including 22 KIV-2 CNV is defined as low molecular weight, whereas large apo(a) isoforms with >22 KIV-2 CNV is defined as high molecular weight (Fig. 1).31 An individual may carry a small and a large isoform, two large ones, or two small ones. Approximately, 20% of subjects express only one isoform as protein, although two isoforms are transcribed at the DNA level.36 However, plasma Lp(a) levels are driven largely by the small isoforms.2, 39 Individuals with small apo(a) isoforms have higher Lp(a) concentrations and 2–4 fold higher risk of CAD.37 In contrast, individuals carrying large apo(a) isoforms have low Lp(a) levels and no increase in risk of CAD.36, 40 Kamstrup et al14, 41 used MR design in 41,231 individuals and demonstrated an association between KIV-2 genotype to both Lp(a) level and AMI as well as atherosclerotic stenosis (in coronary, carotid, and femoral arteries). Both smaller apolipoprotein(a) isoform size and increased Lp(a) concentration are independent and causal risk factors for CAD.2

2.5. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and Lp(a) levels

In addition to KIV-2-CNV, several single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) in the wider LPA region (LPA SNPs) show pronounced associations with small Lp(a) isoforms and Lp(a) concentration.9 Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have identified more than 200 SNPs, with varying prevalence and influence on Lp(a) levels.42 Some of these SNPs are associated with elevated Lp(a) levels, while others are associated with low Lp(a) levels.1 LPA genetic risk score consisting of specific genetic variants have also been associated with incident CAD and CVD.42 Two of these LPA SNPs (e.g. rs10455872 and rs3798220) account for 36% of resultant Lp(a) levels.17, 36, 37 In a genetic study involving individual-level data from 112,238 subjects in the UK Bio bank, the researchers examined the effects of both common and rare variants as well as gain-of-function variants that increase Lp(a) levels and loss-of-functions variants that decrease Lp(a) levels.25 The effect of these different variants on CAD was consistently proportional to their effect on Lp(a) concentrations. One standard deviation (SD) of genetically lowered Lp(a) level was associated with a 29% lower risk of CAD,25 whereas variations in genes associated with higher high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations were not associated with improved CVD risk.1, 2

2.6. Oxidized phospholipids

Lp(a) not only contains all the proatherogenic components of LDL but also of apo(a). Apo(a) potentiates atherothrombosis through its content of the proinflammatory oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs).2, 43, 44 OxPL is a general term that encompasses a large number of individual species. Up to 90% of all OxPLs found in human lipoproteins are carried on Lp(a), and clinical studies have demonstrated that the OxPL on Lp(a) mediates arterial wall inflammation and promotes monocyte inflammatory responses in humans.43 Besides, levels of OxPL on Lp(a) [measured as OxPL-apoB and OxPL-apo(a)] are robust predictors of CVD events and CAVD.2, 43, 44

3. Lp(a) is an important risk factor for CVD

3.1. Epidemiologic studies

In epidemiologic studies, elevated Lp(a) concentrations are associated with a 2-fold risk of CAD (on multivariate analysis, after adjusted for other risk factors).13, 26, 45, 46 However, in three cohorts of women, Lp(a) was associated with CVD only among those with high cholesterol (>220 mg/dl), and improvement in prediction was minimal.47 But, epidemiologic studies generally underestimate the risk because they capture the effects of exposure for a limited period of time (usually 5–10 years).12 Such studies cannot eliminate the concomitant presence of various confounding factors and also cannot exclude reverse causality—elevated Lp(a) resulting from disease rather than causing disease.12

3.2. Genetic studies establish Lp(a) as a causal factor

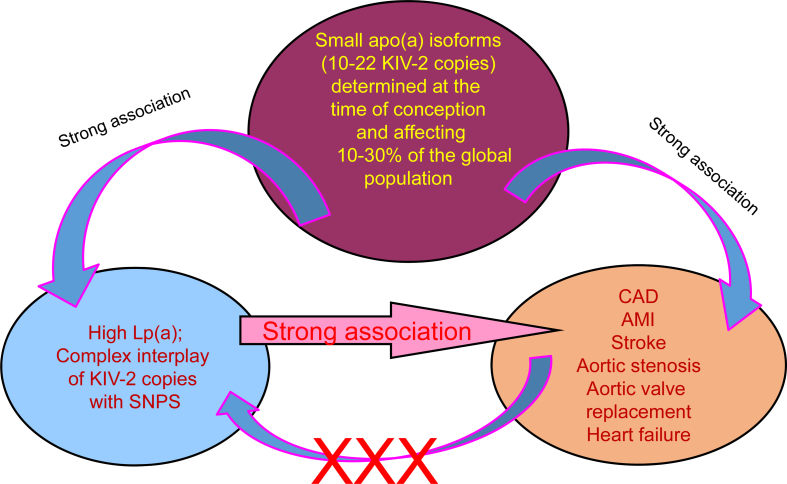

The limitations of epidemiologic studies are overcome by genetic and by MR studies.12 The random assortment of genes from parents to offspring at conception is termed MR.37 The laws of Mendelian genetics, by its nature, ensure that randomization of individual genotype is comparable to those of randomized controlled trial designed by scientists.37 An association of the genotype with disease supports causality17, 36, 37 because population distributions in risk alleles are generally uninfluenced by behavioral and environmental factors and because associations due to reverse causality are excluded (Fig. 2).12, 37

Fig. 2.

Mendelian randomization approach to demonstrate causal association between Lp(a) concentrations and CVD (Ref 12,37).

MR studies and GWAS have established Lp(a) as genetic and causal risk factor for CAD.9, 17, 26 Such studies show a log–linear and potent relationship of Lp(a) to CVD risk—a multivariable-adjusted 3-fold risk of MI among those in the top quintile of Lp(a) levels compared with the bottom quintile (Table 2). This greater magnitude of risk in genetic studies is best explained by the absence of various confounding factors as well as the lifelong exposure. An updated review of epidemiologic and MR studies from Copenhagen population showed that increased CVD risk starts at Lp(a) level as low as 20–30 mg/dl.9 Lp(a) was measured in fresh samples, using isoform-insensitive assay in 58,340 subjects and 1897 validated AMI; the study focused on extreme levels and corrected for regression dilution bias.9 The odds ratio (OR) for CAD with Lp(a) ≥100 mg/dl versus 5 mg/dl was 2.4—a value 40% higher than that reported by the Emerging Risk Factor Collaboration (OR 1.7).9, 26

Clarke et al17 identified several LPA SNPs that were associated with AMI, the strongest being rs10455872 (OR 1.7) and rs3798220 (OR 1.92). A genotype risk score (GRS) involving both SNPs revealed an OR for MI of 1.51 for carriers of one variant and 2.57 for carriers of ≥2 variants.17 A meta-analysis of GWAS involving approximately 185,000 CAD cases and controls interrogated 9.4 million allele variants and confirmed a significant association of Lp(a) genotype with CAD.48 Genetic imputation was based on 1000 G project, but participants were not part of the 1000 G project. Genetic studies by Helgadottir et al,20 Clarke et al,17 Nordestgaard et a l,9 Emdin et al,25 Kamstrup et al,14, 49 and Erqou et al,13 link LPA genotype and GRS with high Lp(a) levels and increased risk of CAD, thereby establishing causality.12, 50

3.3. Global burden of LP(a)

At any level of LDL-C, ASCVD events rate are a 2–3-fold risk higher, when Lp(a) level is elevated.1, 9, 26, 46, 51, 52, 53 The risk increases further with increasing Lp(a) concentrations.11 The ASCVD risk from elevated LP(a) is generally similar in magnitude to each of the established major risk factors (hypercholesterolemia, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, etc).29, 54 Unlike other established risk factors and similar to homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, Lp(a) levels influence atherogenicity from birth.2 Unlike the established risk factors, Lp(a) levels influence atherogenicity from birth.2 High Lp(a) level ≥50 mg/dl is found in 10%–30% of the population with an estimated 1.43 billion people affected globally (Table 3).1 This estimated global prevalence is 3 times higher than that for diabetes which affects 415 million adults with an age-standardized prevalence of 8.5% in adults (2015 data).55 Given the 3-fold difference in the number of affected people and similar OR for ASCVD, the estimated disease burden of elevated Lp(a) surpasses diabetes globally. Of note, the 2018 NHLBI report states that “Lp(a) levels in the atherothrombotic range are generally accepted as ≥30 to 50 mg/dl or ≥75–125 nmol/L”1 The prevalence of Lp(a) may be even higher, if this lower atherothrombotic range is considered instead of ≥50 mg/dl.

Table 3.

Estimated world population with elevated lipoprotein(a) > 50 mg/dl or >125 nmol/l. Ref 1.

| Region/country | Prevalence | Absolute numbers |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 30% | 376 million |

| Europe | 20% | 148 million |

| Australia | 20% | 8 million |

| North America | 20% | 73 million |

| Latin America | 13% | 97 million |

| Asia/China | 10% | 261 million |

| South Asia | 25% | 469 million |

| Global | 10% to 30% | 1.43 billion |

4. Coronary atherosclerosis and acute myocardial infarction

4.1. Rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis

A high Lp(a) level is strongly associated with the extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis and total coronary plaque burden, in apparently healthy people.56, 57, 58, 59, 60 High levels are highly correlated with rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis—a strong predictor of adverse outcome.61, 62, 63, 64, 65 Many vulnerable plaques undergo repeated silent rupture and healing, resulting in rapid progression of atherosclerosis—a process well-documented in the left main coronary artery.60, 61, 66, 67, 68, 69

4.2. Vulnerable plaque and acute coronary syndrome

Coronary atherosclerosis clinically manifests as acute coronary syndrome (ACS) when a ruptured plaque with superimposed thrombosis causes abrupt cessation of blood supply.70 Patients with high Lp(a) levels develop high-risk vulnerable plaques with complex morphology (heavy macrophage infiltration, large necrotic lipid core, thin fibrous cap, etc) that are prone to rupture.71, 72 Large amounts of Lp(a) are detected in culprit lesions of patients with ACS compared with stable angina.56, 73 Elevated Lp(a) levels correlate with both presence and severity of ACS.74, 75, 76 The age at occurrence of a first AMI and ACS is inversely related to Lp(a) levels with the strongest correlation in those < 45 years of age.77, 78, 79 A recent large study of ACS patients (1457 cases and 2090 age-sex matched adults free of CVD) has further confirmed this stronger association of Lp(a) at younger ages. After adjusting for established risk factors, elevated Lp(a) (≥50 mg/dL) was associated with a 3-fold likelihood of ACS in younger adults (<45 years) and a 2-fold likelihood in middle aged (45–60 years) adults, but no association in the older participants (≥60 years).76

4.3. Acute myocardial infarction

People with high Lp(a) levels generally manifest with ACS and large AMI, rather than stable angina.16, 32, 41, 56, 78, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 Hoefler et al86 evaluated Lp(a) levels in 1500 young military recruits and reported that parents of sons with Lp(a) ≥25 mg/dl had a 2.5-fold higher risk of MI compared with parents whose sons had lower Lp(a) levels. Kamstrup et al41 have shown that in smoking hypertensive women ≥60 years of age, the absolute 10-year risk of AMI was 10% and 20% with Lp(a) concentrations <5 mg/dl and ≥120 mg/dl, respectively; the corresponding values in men were nearly double at 19% and 35%.41 A meta-analysis from 11 studies in secondary prevention reported that patients with higher levels of Lp(a) had significantly more recurrent AMI and MACE.84 Elevated Lp(a) was the only variable in recurrence of AMI in many studies.84 In a 3-year follow up of 79 male survivors of AMI in Stockholm (Sweden), 16 patients had recurrent (9 fatal) MI.84 Compared with the general population, Lp (a) levels were double in AMI survivors and four times higher in those who had recurrent AMI.84 Another study (n = 232; aged 50–53 years) reported that Lp(a) was the principal driver of recurrent MACE during a follow-up of 11 years.84 Twenty-six (11%) men with the highest Lp(a) levels had the highest incidence of recurrent MACE (4 times higher than the lowest quartile) and accounted for 33% of MACE.84 It is also notable that high Lp(a) level is an underappreciated contributor to AMI during pregnancy.80

4.4. Restenosis following coronary artery revascularization procedures

Lp(a) is a predictor of restenosis after coronary artery revascularization procedures (CARPs) (coronary angioplasty, stent, coronary bypass surgery).87, 88 A mechanism appears to be a preferential accumulation of Lp(a) compared with LDL at injured sites.9, 89, 90, 91, 92 A meta-analysis of nine cohort studies involving 1834 patients suggested that elevated plasma Lp(a) level is associated with in-stent restenosis.93 Significant reduction in restenosis rates has been noted by lowering Lp(a) through lipoprotein apheresis.90

4.5. Lp(a) accentuates ASCVD risk in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) is an inherited genetic disorder that causes dangerously high cholesterol levels, which can lead to heart disease, MI, or stroke at an early age if left untreated. The possibility of HeFH should be considered if LDL-C is ≥ 155 mg/dl in those younger than 18 years and ≥174 mg/dl for age group 18 to 39 years.94 Lp(a) levels are significantly higher in approximately 25% of people with clinical HeFH and place them at a greater risk of CAD.95, 96, 97, 98 In the prospective Copenhagen Cohort Study (n = 46,200), the hazard ratio (HR) for AMI was 1.0 for those who had neither HeFH nor Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl.96 The HR for AMI was 3·2 (2·5–4·1) for patients with HeFH alone, which increased to 5·3 (3·6–7·6) among those having a HeFH and Lp(a) ≥50 mg/dL.96 Thus, measurement of Lp(a) in patients with a HeFH helps identify those with highest risk for AMI.

4.6. Lp(a) in CVD risk reclassification

Addition of LPA risk genotypes or Lp(a) level to the established risk factors improves the prediction of CAD and AMI in primary prevention.41, 99, 100 In the prospective Copenhagen City Heart Study100 (n = 8720), the inclusion of the top quintile of Lp(a) (≥47 mg/dl) resulted in a 100% correct reclassification of all patients, who experienced MACE over 10 years; no events were reclassified incorrectly.100 Likewise, in 15 years of prospective follow-up of 826 men and women in the Bruneck Study, 148 developed CVD. In models adjusted for major risk factors, the OR for incident CVD was 2.37 in the top fifth quintile versus the bottom quintile of Lp(a) levels.99 Besides, Lp(a) levels helped reclassify 40% of individuals initially categorized as intermediate risk into higher risk or lower risk categories.99 When the need for statin therapy is uncertain such as people with a 10-year risk of 5–7.5% (estimated by using the Pooled Cohort Equation), the inclusion of Lp(a) with a threshold of ≥30 mg/dl significantly improves CVD prediction.101, 102 Thus a case is evident to include Lp(a) level in ASCVD risk calculators.

4.7. Lp(a) is an important determinant of residual risk

Evidence from randomized outcome trials of statin, ezetemibe, niacin, and PCSK9 inhibitor have shown that at any achieved LDL-C level, MACE rates are higher, when Lp(a) is elevated, suggesting an unaddressed Lp(a)-mediated risk.1, 42, 103, 104, 105 In one such outcome trial, carotid atherosclerosis continued to progress in those elevated Lp(a) levels, despite lowering LDL-C to <65 mg/dL.106 Besides, those with Lp(a) ≥50 mg/dl had an 89% higher risk of MACE compared with those with low Lp(a).107 Such residual risk has been documented, even among those with LDL-C <55 mg/dl in primary prevention.27

4.8. Lp(a) is an important prognostic factor

Elevated levels of Lp(a) levels are associated with greater morbidity and mortality after adjusting for established risk factors and the extent of CVD.26, 105, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113 This is also true of patients with AMI and treated with or without CARP.105, 108, 110, 114, 115, 116, 117 In the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S), the overall mortality reduction was 30% but varied markedly by the Lp(a) levels. The mortality reduction was 4-fold higher in the lowest quartile of Lp(a) vs the top quartile (58% vs14%).118 More recent prospective data show a continuous and independent association between Lp(a) levels and risk of sudden cardiac deaths in the general population (with no known CAD).119

5. Lp(a): ethnicity affects Lp(a) levels and consequent CVD risk

5.1. Ethnic differences in Lp(a) levels

The NHLBI report estimated the absolute number of world population with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl as 1.43 billion, with prevalence varying from 10% to 30% (Table 3).1 It is known that population mean and median levels of Lp(a) vary by race and ethnicity.1, 120, 121, 122, 123 Lp(a) concentrations are lower in Hispanics than in whites124; Chinese newborns have lower levels than in Indian newborns.125 Native Americans (American Indians) have the lowest Lp(a) levels with a median Lp(a) concentration of 3.0 mg/dl.126 In whites (populations of European descent), Lp(a) distribution is highly skewed to the right. For example, in the Framingham Offspring Study, 56% of the Lp(a) values were in the range of 0–10-mg/dL, and 70% had <20 mg/dl.127 Blacks, both Africans, and African Americans have 2 to 3 times higher levels of Lp(a) than in whites, and their Lp(a) distribution is closer to a Gaussian distribution.12, 37 But controversy abounds regarding CVD risk imparted by Lp(a) in blacks compared with whites as results of studies span the whole range: higher, similar, and lower to none.121, 122 Circulating levels of Lp(a) predict MACE irrespective of the ethnicity, LPA SNPs, or isoform.121, 123

5.2. The INTERHEART-Lp(a) study

The INTERHEART study is a large international standardized case–control study designed to determine the association between various risk factors and non-fatal AMI in a total of 15,152 cases and 14,820 controls from 52 countries.29 Cases were defined as those who were admitted to a coronary care unit or equivalent cardiology ward within 24 h of clinical characteristics of a new MI. Controls were stratified by ethnicity and adjusted for age and sex, had no previous diagnosis of heart disease, and were recruited from hospital or community-based settings. Plasma concentrations of Lp(a) were measured in seven major ethnic groups (6086 first AMI cases and 6859 controls and matched by ethnicity), using an immunoassay from Denka Seiken, which included a 5-point calibrator that minimizes the effect of apo(a) isoforms size.11 The median Lp(a) level was 11 mg/dl in controls and 13 mg/dl in cases for the entire study population with marked variation among the ethnic groups. Chinese had the lowest, and Africans had the highest Lp(a) levels, with South Asians having the second highest levels. When all ethnic groups are combined, there was a 48% higher risk of AMI in those with high Lp(a) (defined as ≥50 mg/dl).11 However, marked intergroup differences were noted (Table 4).11 High Lp(a) did not raise the risk of AMI in Africans and Arabs, who were the two smallest groups. When the data were reanalyzed excluding the two groups, the AMI risk from high Lp(a) for the rest increased to 58%. Most notably, elevated Lp(a) concentration conferred the highest OR for AMI [OR 2.14 (159–2.89 p < 0.001)] and highest population attributable risk (PAR 10%) in South Asians (adjusted for age, sex, apo A, and apo B).11 Key findings and implications of this landmark study are summarized in Table 4, Table 5.11

Table 4.

Ethnic differences in the risk of acute myocardial infarction from lipoprotein(a) > 50 mg/dl (adjusted for age, sex, apo A, and apo B) Ref 11.

| Ethnicity | Number of participants |

% of participants with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl % |

OR (95% CI) for AMI for Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | P-value | |

| Europeans | 951 | 897 | 17.7 | 13.5 | 1.36 (1.05–1.76) | 0.021 |

| South Asians | 948 | 870 | 18.2 | 8.51 | 2.14 (1.59–2.89) | <0.001 |

| Chinese | 2034 | 2385 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 1.62 (1.20–2.15) | 0.002 |

| Southeast Asians | 600 | 607 | 12.5 | 6.6 | 1.83 (1.17–2.88) | 0.009 |

| Latin Americans | 731 | 732 | 20.9 | 13.6 | 1.67 (1.25–2.22) | <0.001 |

| Arabs | 528 | 822 | 14.8 | 12.0 | 1.13 (0.80.59) | 0.485 |

| Africans | 294 | 474 | 25.9 | 26.6 | 0.92 (0.65–1.31) | 0.659 |

| Summary | 6086 | 6789 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 1.48 (1.32–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Heterogeneity | 0.007 | |||||

Apo A = apolipoprotein A; apo B = apolipoprotein B; Lp(a) = lipoprotein(a); NA = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; CI =confidence interval; AMI, .

Table 5.

Principal results and implications of the INTERHEART-Lp(a) study (Ref 11).

| 1 | Elevated Lp(a) concentration and the risk of AMI conferred by elevated Lp(a) vary significantly by ethnicity. |

| 2 | The median Lp(a) concentration varies 3-fold with the Chinese manifesting the lowest (8 mg/dl) and Africans manifesting the highest concentration (27 mg/dl). |

| 3 | The prevalence of elevated Lp(a) levels varies 7-fold when a threshold of Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl is used. |

| 4 | Higher Lp(a) concentrations are consistently associated with risk of AMI (except in Africans and Arabs). The latter might have been due to small number of study participants. |

| 5 | The odds ratio (OR) for AMI using a threshold of Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl, adjusted for smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and ApoB/Apo A1 ratio is 1.48; the OR increases to 1.58, when Africans and Arabs are excluded from analysis. |

| 6 | The OR for AMI from high Lp(a) concentrations is highest in South Asians (OR 2.14), followed by South East Asians (OR 1.83), Latin Americans (OR 1.67), Chinese (OR 1.62), and Europeans (OR 1.36). |

| 7 | The population attributable risk (PAR) for AMI from Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl is highest in South Asians (PAR 10%), followed by Latin Americans (PAR 8%), South East Asians, and whites (PAR 5%). |

| 8 | The results support clinical use of Lp(a) concentration measured with an assay insensitive to isoform size as a marker of AMI risk in diverse populations, especially in South Asians. |

| 9 | Confirmed the inverse relationship between Lp(a) concentrations and isoform sizes in seven largest ethnic groups. |

| 10 | Underscored the need for accelerated development of new effective Lp(a) lowering drugs. |

ApoB/Apo A1 = apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1; AMI = acute myocardial infarction; HDL-C = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a) = lipoprotein(a).

5.3. Various thresholds and the need for ethnic-specific thresholds

An updated review of epidemiologic and MR studies from Copenhagen population concluded that Lp(a) ≥20–30 mg/dl (50–75 nmol/l) is the atherothrombotic range.9, 16, 41, 128 This new analysis included 58,340 subjects, measured Lp(a) in fresh samples using isoform-insensitive assays, corrected for regression dilution bias, recorded 1897 validated AMI, and also focused on those with extremely high Lp(a) levels.9 Lp(a) ≥30 mg/dl approximates the 75th percentile in white populations,127 and those exceeding 75th percentile have a 2–3-fold risk of CAD1, 54, 129; this value was used as the risk threshold in the United States until 2018.54, 129, 130 However, the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel chose a higher threshold of ≥50 mg/dl or ≥125 nmol/L.5 This value corresponds the 80th percentile for European population5 and 90th percentile for predominantly white population of Framingham Heart Study (generally considered the standard for the US population).127 The NHLBI reviewed the two vastly different Lp(a) thresholds across the Atlantic Ocean and arrived at a compromise range rather than a threshold.1, 5, 129 Their recommendation (published in 2018) is that “Lp(a) levels in the atherothrombotic range are generally accepted as >30–50 mg/dl or 75–125 nmol/L”1

6. Lp(a) and non-coronary diseases

The range of associated phenotypes associated with high Lp(a) has recently been broadened.25, 131 One SD in genetically lowered Lp(a) level is associated with a 29% lower risk of CAD, 31% lower risk of PAD, 13% lower risk of stroke, 17% lower risk of heart failure, 37% lower risk of CAVD, and 9% lower risk of CKD.25 There was no association with diabetes, atrial fibrillation, or venous thromboembolism.25

6.1. Ischemic stroke in adults and children

Elevated Lp(a) level is a risk factor for carotid stenosis and ischemic stroke.14, 25, 26, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136 In a meta-analysis of stroke studies, the summary OR for ischemic stroke from elevated Lp(a) was comparable to thrombophilia.137 Of note, the risk of hemorrhagic stroke is reduced in patients with high Lp(a) levels.138 Lp(a) is a particularly strong predictor of ischemic stroke in neonates,139 children,140, 141 and young adults.142 Children with high Lp(a) levels have a 4-fold risk of ischemic stroke with an even higher risk for recurrent stroke.143, 144, 145 The ischemic stroke risk is increased as high as 10-fold in those with Lp(a) > 90th percentile.140

6.2. Calcified aortic valve disease and heart failure

Severe CAVD results in approximately 50,000 valve replacements and 22,000 deaths annually in the United States alone.146 An elevated Lp(a) levels is a strong, causal, and an independent risk factor for CAVD.21, 22, 24 Lp(a) ≥50 mg dl is associated with double the risk of CAVD compared with those below this level.147 Kamstrup et al148 evaluated the causal role of elevated Lp(a) in heart failure using MR design. During a follow-up of 98,097 healthy subjects (from 1976 to 2013), 4122 were diagnosed with heart failure. Those with Lp(a) ≥20 mg/dl (60th −90th percentile) had a 24% increased the risk of heart failure; the risk was doubled in those with Lp(a) ≥67 mg/dl (>90th percentile p value for trend < 0.001), corresponding to a PAR of 9%. Risk estimates were substantially reduced when those with MI and CAVD were excluded, indicating that most of the risk for heart failure was mediated by these two conditions.148

6.3. Lp(a) and other vascular and non-vascular diseases

High Lp(a) levels are highly correlated with PAD in people with and without diabetes.23, 149, 150, 151, 152 Other vascular disorders associated with elevated Lp(a) level include abdominal aortic aneurysm,153 aortic thrombosis,154 aortic dissection,155 left atrial thrombus,115 ischemic cardiomyopathy,156 retinal vascular occlusion,157 and intracranial stenosis.133 Elevated Lp(a) is a sensitive indicator of the severity of target organ damage and MACE in patients with hypertension and is a predictor of CKD, as well CAD and MACE in patients with CKD.1, 5, 85, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162 Lp(a) level begins to increase in early stages of renal impairment163 and increases as much as 3-fold in those with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.

7. Lp (a): measurements and interpretation

7.1. Use only isoform-insensitive Lp(a) assay: lessons from Physician's Health Study

Differing Lp(a) particle sizes with more than 40 isoforms provide unique challenges to standardize the Lp(a) assays. As discussed earlier, small isoforms are associated with high Lp(a) levels and high risk of CAD, whereas large isoforms are associated with low Lp(a) levels and no CVD.1 Earlier Lp(a) assays which were isoform sensitive overestimated Lp(a) levels when the Lp(a) isoforms were large and underestimated the Lp(a) levels when Lp(a) isoforms were small.12, 129 The pitfall of using an isoform-sensitive assay is best illustrated by three Physician's Health Studies (PHSs) that sadly set the clock back on Lp(a) research by over 2 decades.164, 165, 166 The enthusiasm for Lp(a) research in the 1980s was dampened by these reports that failed to show any association of Lp(a) with MI, stroke, or PAD.164, 165, 166 By the time the fourth PHS was initiated, Marcovina et al167, 168 had developed and validated an isoform-insensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which has become the reference standard for measuring Lp(a) level. An extensive review of numerous issues affecting Lp(a) has been published recently.168

Rifai et al52 measured Lp(a) levels using the reference standard ELISA in PHS participants who developed severe CAD and angina. This study showed a strong relationship between Lp(a) levels and CAD, with 35% higher Lp(a) levels in cases than in controls (p = 0.02).52 The CAD risk was increased 2-fold in those with Lp(a) > 80th percentile and a 4-fold in those with Lp(a) > 95th percentile. In contrast, there was no association of Lp(a) levels and CAD when Lp(a) was measured in duplicate with the commercial assay used in the first three PHSs.52 The Women's Health Study and all other subsequent studies using isoform-insensitive Lp(a) assays have shown a strong correlation between Lp(a) and ASCVD.11, 26, 45, 46, 53 These data underscore the importance of using only isoform insensitive assays in measuring Lp(a) levels.

7.2. Selective decrease in high Lp(a) levels on stored serum

Small Lp(a) isoforms (that predominate in CVD patients with high(a) levels) deteriorate significantly than larger isoforms in specimens stored for years and decades.169 As a result, the differences in Lp(a) levels between cases and control may narrow or disappear. This phenomenon probably explains why Prospective Cardiovascular Munster study and others that measured Lp(a) levels in fresh plasma found a strong association of Lp(a) ≥20 mg/dl with AMI (OR 2.7),28, 78 in contrast to ≥30–50 mg/dl in specimens stored for an extended period of time.1, 2

7.3. Lp(a) cholesterol -does not predict CVD risk

Healthcare providers have used Lp(a) cholesterol (Lp(a)-C) estimated by the Vertical Auto Profile method (VAP-LP(a)-C) to assess the Lp(a)-related risk in millions of patients. Yeang et al170 have recently shown that VAP method may have been measuring the HDL-C rather than Lp(a)-C. This probably explains why VAP-Lp(a)-C levels are discordant with Lp(a) particle number.171, 172 Besides, VAP Lp(a)-C has not been validated for prediction of CVD outcomes.168 Accordingly, all those who previously had VAP-Lp(a)-C measurements done should consider reevaluating the Lp(a)-related risk with alternative accurate Lp(a) assays.170

7.4. World Health Organization International Federation Of Clinical Chemistry Reference Material for Lp(a) immunoassay

To standardize the measurement of Lp(a) assay, the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) developed a Reference Material using a monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes KIV-9 (and not KIV-2 repeats) and assigned a value of 107 nmol/l in 2004. Upon acceptance by the World Health Organization (WHO), this became the World Health Organization International Federation of Clinical Chemistry Reference Material (WHO/IFCC RM) for Lp(a) immunoassays.173 But the assays remained isoform-sensitive until an expert panel led by Macovina et al129, 167, 168, 174 developed a reference ELISA method not sensitive to apo(a) isoform size.1 In a comparative study involving 19 different commercial assays, the one with the best concordance with the reference ELISA assay was a latex-enhanced turbidimetric assay developed by Denka Seiken.129, 168 The impact of isoform size variation is reduced or eliminated by the use of five different calibrators.129, 168 Lp(a) concentration in these assays are traceable to WHO/IFCC RM, and the results are reported in nmol/l. It is worth highlighting that NHLBI recommends assays to report values in apo(a) particle number as nmol/l and not mg/dl.1, 168 It also cautions against measuring Lp(a) mass and converting to nmol/l by multiplying with factor (usually 2.5).129 Precise methods and Lp(a) kits based on the Denka reagent that can be run through almost all chemical analyzers are available (in the US and India).*The test is available at most hospitals and outpatient laboratories in the United States. In a welcome step, such isoform-insensitive assay is available for clinical use through commercial enterprises in the United States.**

7.5. Indications for measuring Lp(a)

The indications for measuring Lp(a) are listed in Table 6.5, 175 Levels can be measured any time beyond age 2 years after which the levels do not change.125, 176 Given that Lp(a) levels are genetically predetermined and remain stable over one's life, a single measurement of Lp(a) during a lifetime is generally sufficient. At a cost of $ 25 to $100 for an Lp(a) test (similar to that of a standard lipid profile), a onetime measurement of Lp(a) is cost effective in ASCVD risk assessment.

Table 6.

| 1 | Personal history of premature CVD. |

| 2 | Family history of premature CVD and/or elevated lipoprotein(a) levels. |

| 3 | Subjects with familial hypercholesterolemia. |

| 4 | Recurrent CVD events despite high-intensity statin treatment. |

| 5 | Subjects with statin resistance (<50% reduction in LDL-C, in spite of high intensity statin therapy). |

| 6 | Subjects whose need for and/or intensity of statin therapy are not clear. |

CVD = cardiovascular disease; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

8. Management strategies for elevated Lp(a)

Lp(a) levels are refractory to lifestyle interventions. The gold standard of a double-blind randomized control trial to test the Lp(a) a hypothesis that specifically reducing Lp(a) level leads to ASCVD and CAVD risk reduction has not been carried out to date. Although several drugs are in advanced stages of development,177 present management strategies include cascade screening and aggressive prevention and control of all modifiable risk factors.2, 178

8.1. Cascade screening and prevention of modifiable risk factors

An Australian study of 2010 white children aged 6–12 years showed that their Lp(a) levels were predictive of both premature onset and severity of CAD in their grandparents.179, 180 The study also substantiated that the children's Lp(a) tracks the best fit parent or grandparent rather than the average of levels in two parents or four grandparents.179, 180 Other studies have shown Lp(a) is one of the strongest biological mediators of family history of premature CVD.181, 182, 183 High Lp(a) is strongly associated with coronary plaque volumes, extent, and severity in apparently healthy people.184 Asymptomatic individuals with family history of premature ASCVD or high calcium score should have Lp(a) measured.182, 184 In those with high Lp(a), it is vital to prevent or reduce modifiable risk factors, e.g., prevent acquisition of smoking habit, cease tobacco use, and reduce LDL-C. In young women with elevated Lp(a) levels, the potential thrombotic risk from oral contraceptives must be weighed against discontinuation or use of lowest risk formulations.

8.2. Low-dose aspirin

The Women's Health Study used carriers of an apo(a) genetic variant (rs3798220) as a proxy for elevated Lp(a). The study found double the CVD risk in carriers compared with non-carriers. More importantly, low-dose aspirin therapy markedly reduced CVD risk in carriers (56%) but not in non-carriers.18 Others have shown up to 80% reduction with low-dose aspirin in those with very high serum Lp(a) concentrations (>30 mg/dl).185

8.3. High-intensity statin therapy

The highest priority in management of high Lp(a) is to lower LDL-C to the lowest safe levels, especially in the young with risk factors or rapidly progressing CVD.177, 186 Randomized clinical trials, observational reports, and MR studies are also forcing a reconsideration of what "normal" LDL-C means. A recent meta-analysis has clearly demonstrated the safety and benefits of lowering LDL-C from 65 mg/dl to as low as 21 mg/dl. In this analysis, 1 mmol/l (38.7 mg/dl) reduction in LDL-C was associated with a 21% reduction in MACE.187 This was comparable to 22% reduction in MACE for the same magnitude of reduction in LDL-C from a higher baseline LDL-C (from 140 to 100 mg/dl).187

Patients with Lp(a) level ≥50 mg/dl are considered high risk even in the absence of other risk factors.188, 189 The 2018 Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines have included Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl as an ASCVD risk enhancer in initiating and intensifying statin therapy.175 In very high-risk individuals [such as those with CVD, diabetes, and high Lp(a)], ezetemibe and/or PCSK9 inhibitors may be necessary if maximally tolerated statin therapy fails to bring the LDL-C to <70 mg/dl.175 Intensity of therapy is reduced only if LDL-C remains <25 mg/dl on two consecutive occasions 4 weeks apart.175

8.4. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors regulate LDL receptors via increased recycling (versus increased synthesis that occurs with statins).190, 191, 192 Two large-scale outcome trials have been competed with evelocumab and alirocumab; both are approved for clinical use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in United States. These agents lower LDL-C by 60% and also lower Lp(a) by 30%. Although Lp (a) was a determinant of the achieved LDL-C in the Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk (FOURIER) trial, FDA has not expanded the indications for the use of PCS K9 to lower Lp(a).193 In patients with CVD and LDL-C ≥70 mg/dl on statin therapy, evelocumab lowered LDL-C to a median of 30 mg per deciliter and reduced MACE by 15%.193 The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization. There was a monotonic relationship between achieved LDL-C and MACE down to LDL-C concentrations <10 mg/dl. Importantly, there were no safety issues with very low LDL-C concentrations over a median of 2.2 years.193

In the Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment With Alirocumab (ODYSSEY OUTCOMES) trial, a significant reduction in all primary and secondary endpoints was observed in those who were randomized to alirocumab.194 The primary endpoint was a composite of death from CAD, nonfatal MI, fatal and nonfatal stroke, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization. The risk reduction was 15% for both composite primary endpoint and all-cause death, 12% for CVD death, 27% for fatal and nonfatal stroke, and 39% for unstable angina requiring hospitalization.194 PCSK9 inhibitors are costly, but in assessing cost effectiveness, the number of initial and recurrent MACE prevented in high-risk patients must be factored.195

8.5. Lipoprotein apheresis

An 11-year old boy presented with multiple thrombotic strokes secondary to elevated Lp(a) as the only identified risk factor and was treated promptly with lipoprotein apheresis (LA).144 Eighteen months poststroke, he is still receiving LA treatments and has made remarkable progress in his recovery without another cerebrovascular event.144 In the United States, <50 patients with progressive CAD and elevated Lp(a) are receiving LA therapy compared with >1500 patients in Germany.196 Apheresis is expensive, burdensome, and unavailable in most countries. Notable exceptions are Germany and UK, as they bear the cost of apheresis treatment for ASCVD patients with Lp(a) levels ≥60 mg/dL together with progressive CVD and recurrent MACE or uncontrolled LDL-C.2 Weekly LA removes all apoB-containing lipoproteins including Lp(a) by 60–70% acutely, but the average reduction is only 30%–35%, because Lp(a) rapidly increases during the interval between the procedures.196 Reseller et al197 have recently reported the 5-year follow-up of a prospective LA trial in 170 patients (mean age 49 years) with markedly elevated Lp(a) (108 mg/dl) and progressive CVD, despite maximally tolerated statins (LDL-C <100 mg/dl). The annual incidence of MACE during 5 years of LA was reduced by 85% compared with rates in the 2 years prior to LA.197 The effects may have been exaggerated because of lack of randomization and the use of historic control rather than simultaneous control. Jaeger et al198 have reported similar impressive results—a 75% reduction in Lp(a) and 63% reduction in LDL-C levels and a highly significant 86% (P < 0.0001) reduction in MACE. A creative international clinical trial of LA therapy (NCT02791802) is currently underway with German sites randomized to LA and non-German sites to “usual care”.1

8.6. Selective Lp(a) apheresis

Safarova et al199 used intensive statin therapy to lower LDL-C < 100 mg/dl in patients with Lp(a) ≥50 mg/dl. Subsequently, one-half of the patients received weekly Lp(a) apheresis for 18 months on top of statin therapy, while the other half (statin only) served as the control. Lp(a) apheresis reduced Lp(a) levels by 73%, resulting in regression of atherosclerosis as measured by quantitative coronary angiography, compared with controls. These studies strengthen the concept that CAD risk can be reduced by lowering Lp(a) level.

8.7. Novel therapies to lower Lp(a)

The inhibition of apo(a) gene expression is a focus of intense research.161 Antisense oligonucleotides are a class of synthetic analogs of nucleic acid that selectively bind to target mRNA, preventing their translation and secretion. Antisense therapy markedly lower plasma Lp(a) levels even in those with very high pretreatment Lp(a).200, 201 Two such agents ISIS-APO(a) and IONIS-APO (a)-LRx have shown to lower Lp(a) and OxPL by 78%–90% with no apparent adverse effects.200 This new technology represents a new therapeutic paradigm to reduce elevated Lp(a) to normal level.201

9. Conclusions

It has taken more than 50 years after its discovery, for Lp(a) to finally come of age. Research scientists, but not practicing clinicians, have recognized Lp(a) as an independent genetic causal factor for ASCVD. On the basis of epidemiologic, genetic, and pathophysiological studies summarized in this article, we submit that elevated Lp(a) should be considered as a major risk factor for ASCVD and its various phenotypes. The 2018 Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guideline have recognized elevated Lp(a) as an ASCVD risk enhancer to be considered in initiating or intensifying statin therapy. Although genetic data support Lp(a) levels <20 mg/dl as optimal, the NHLBI of Experts have concluded Lp(a) levels ≥30–50 mg/dl (≥75–125 mg/dl) as the atherothrombotic range. Even when the more conservative threshold of Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl is used to define elevated Lp(a), such levels affect 10%–30% of the global population (compared to 8.5% for diabetes). The INTERHEART-Lp(a) study—with its size, design, and global enrollment highlights the need for ethnic specific Lp(a) thresholds.11 Lp(a) level should be measured by an assay insensitive to isoform size and reported in nmol/l to reflect the Lp(a) particle concentration. Specific therapies to address Lp(a)-mediated CVD and CAVD are in development.

The first golden age of Lp(a) research started in 1987 with the cloning and sequencing of Lp(a) coding for apo(a) in Lp(a).30 The second golden age of Lp(a) research began 22 years later in 2009, with the genetic evidence that Lp(a) is a causal factor and not just a biomarker.16, 17 Studies with potent and specific Lp(a) lowering drugs are currently underway to test the hypothesis that lowering Lp(a) will reduce CVD risk in patients with elevated Lp(a) levels. A third golden age is in the horizon—a period in which effective Lp(a) lowering medications, proven by randomized double-blind clinical trials to reduce CVD risk are approved, available, affordable, and prescribed in accordance with indications.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Sotirios Tsimikas for his valuable suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2019.03.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tsimikas S., Fazio S., Ferdinand K.C. NHLBI working group recommendations to reduce lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(2):177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsimikas S. A test in context: lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(6):692–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capoulade R., Chan K.L., Yeang C. Oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein(a), and progression of calcific aortic valve stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1236–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varvel S., McConnell J.P., Tsimikas S. Prevalence of elevated lp(a) mass levels and patient thresholds in 532 359 patients in the United States. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(11):2239–2245. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordestgaard B.G., Chapman M.J., Ray K. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J. 2010 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afshar M., Pilote L., Dufresne L., Engert J.C., Thanassoulis G. Lipoprotein(a) interactions with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other cardiovascular risk factors in premature acute coronary syndrome (ACS) Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5(4) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boffa M.B., Koschinsky M.L. Lipoprotein (a): truly a direct prothrombotic factor in cardiovascular disease? J Lipid Res. 2016;57(5):745–757. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R060582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt K., Noureen A., Kronenberg F., Utermann G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a) J Lipid Res. 2016;57(8):1339–1359. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R067314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordestgaard B.G., Langsted A. Lipoprotein (a) as a cause of cardiovascular disease: insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(11):1953–1975. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R071233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg K. A new serum type system in man: the LP system. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1963;59:369–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1963.tb01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pare G, McQueen M, Enas Enas, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and Risk of Myocardial Infarction in Seven Major Ethnic Groups (Circulation in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kronenberg F., Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a): resurrected by genetics. J Intern Med. 2013;273(1):6–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erqou S., Thompson A., Di Angelantonio E. Apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and the risk of vascular disease: systematic review of 40 studies involving 58,000 participants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(19):2160–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamstrup P.R., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B.G. Genetic evidence that lipoprotein(a) associates with atherosclerotic stenosis rather than venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(7):1732–1741. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandholzer C., Saha N., Kark J.D. Apo(a) isoforms predict risk for coronary heart disease. A study in six populations. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12(10):1214–1426. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.10.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamstrup P.R., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Steffensen R., Nordestgaard B.G. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. J Am Med Assoc : J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301(22):2331–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke R., Peden J.F., Hopewell J.C. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chasman D.I., Shiffman D., Zee R.Y. Polymorphism in the apolipoprotein(a) gene, plasma lipoprotein(a), cardiovascular disease, and low-dose aspirin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopewell J.C., Clarke R., Parish S. Lipoprotein(a) genetic variants associated with coronary and peripheral vascular disease but not with stroke risk in the Heart Protection Study. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2011;4(1):68–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helgadottir A., Gretarsdottir S., Thorleifsson G. Apolipoprotein(a) genetic sequence variants associated with systemic atherosclerosis and coronary atherosclerotic burden but not with venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(8):722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thanassoulis G., Campbell C.Y., Owens D.S. Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):503–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamstrup P.R., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B.G. Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(5):470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laschkolnig A., Kollerits B., Lamina C. Lipoprotein (a) concentrations, apolipoprotein (a) phenotypes, and peripheral arterial disease in three independent cohorts. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103(1):28–36. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thanassoulis G. Lipoprotein (a) in calcific aortic valve disease: from genomics to novel drug target for aortic stenosis. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(6):917–924. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R051870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emdin C.A., Khera A.V., Natarajan P. Phenotypic characterization of genetically lowered human lipoprotein(a) levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(25):2761–2772. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erqou S., Kaptoge S., Perry P.L. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. J Am Med Assoc : J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302(4):412–423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khera A.V., Everett B.M., Caulfield M.P. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, rosuvastatin therapy, and residual vascular risk: an analysis from the JUPITER trial (justification for the use of statins in prevention: an intervention trial evaluating rosuvastatin) Circulation. 2014;129(6):635–642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assmann G., Schulte H., von Eckardstein A. Hypertriglyceridemia and elevated lipoprotein(a) are risk factors for major coronary events in middle-aged men. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(14):1179–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusuf S., Hawken S., Ounpuu S. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLean J.W., Tomlinson J.E., Kuang W.J. cDNA sequence of human apolipoprotein(a) is homologous to plasminogen. Nature. 1987;330(6144):132–137. doi: 10.1038/330132a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berglund L., Ramakrishnan R. Lipoprotein(a): an elusive cardiovascular risk factor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004 doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000144010.55563.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamstrup P.R., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B.G. Lipoprotein(a) and risk of myocardial infarction--genetic epidemiologic evidence of causality. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2011;71(2):87–93. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2010.550311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Utermann G. The mysteries of lipoprotein(a) Science. 1989;246:904–910. doi: 10.1126/science.2530631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damluji A.A., El-Maouche D., Alsulaimi A. Accelerated atherosclerosis and elevated lipoprotein (a) after liver transplantation. Journal of clinical lipidology. 2016;10(2):434–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbir M., Khaghani A., Kehely A. Normal levels of lipoproteins including lipoprotein(a) after liver- heart transplantation in a patient with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Q J Med. 1992;85(307-308):807–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kronenberg F. Genetic determination of lipoprotein(a) and its association with cardiovascular disease: convenient does not always mean better. J Intern Med. 2014;276(3):243–247. doi: 10.1111/joim.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kronenberg F. Human genetics and the causal role of lipoprotein(a) for various diseases. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30(1):87–100. doi: 10.1007/s10557-016-6648-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawn R.M. Lipoprotein(a) in heart disease. Sci Am. 1992;266(6):54–60. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0692-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saleheen D., Haycock P.C., Zhao W. Apolipoprotein(a) isoform size, lipoprotein(a) concentration, and coronary artery disease: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(7):524–533. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30088-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guadagno P.A., Summers Bellin E.G., Harris W.S. Validation of a lipoprotein(a) particle concentration assay by quantitative lipoprotein immunofixation electrophoresis. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;439:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamstrup P.R., Benn M., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B.G. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. The copenhagen city heart study. Circulation. 2007:176–184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.715698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopewell J.C., Clarke R., Parish S. Lipoprotein(a) genetic variants associated with coronary and peripheral vascular disease but not with stroke risk in the Heart Protection Study. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2011;4(1):68–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Valk F.M., Bekkering S., Kroon J. Oxidized phospholipids on lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans. Circulation. 2016;134(8):611–624. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.020838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Byun Y.S., Yang X., Bao W. Oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 and recurrent ischemic events following stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(2):147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Genser B., Dias K.C., Siekmeier R., Stojakovic T., Grammer T., Maerz W. Lipoprotein (a) and risk of cardiovascular disease--a systematic review and meta analysis of prospective studies. Clin Lab. 2011;57(3-4):143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennet A., Di Angelantonio E., Erqou S. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of future coronary heart disease: large-scale prospective data. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(6):598–608. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook N.R., Mora S., Ridker P.M. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular risk prediction among women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(3):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikpay M., Goel A., Won H.H. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamstrup P.R., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Steffensen R., Nordestgaard B.G. Pentanucleotide repeat polymorphism, lipoprotein(a) levels, and risk of ischemic heart disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(10):3769–3776. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witztum J.L., Ginsberg H.N. Lipoprotein (a): coming of age at last. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(3):336–339. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E066985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamon-Fava S., Marcovina S.M., Albers J.J. Lipoprotein(a) levels, apo(a) isoform size, and coronary heart disease risk in the Framingham Offspring Study. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(6):1181–1187. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M012526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rifai N., Ma J., Sacks F.M. Apolipoprotein(a) size and lipoprotein(a) concentration and future risk of angina pectoris with evidence of severe coronary atherosclerosis in men: the Physicians' Health Study. Clin Chem. 2004;50(8):1364–1371. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.030031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shai I., Rimm E.B., Hankinson S.E. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary heart disease among women: beyond a cholesterol carrier? Eur Heart J. 2005;26(16):1633–1639. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bostom A.G., Cupples L.A., Jenner J.L. Elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease in men aged 55 years and younger. A prospective study. J Am Med Assoc : J Am Med Assoc. 1996;276(7):544–548. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540070040028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogurtsova K., da Rocha Fernandes J.D., Huang Y. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dangas G., Mehran R., Harpel P.C. Lipoprotein(a) and inflammation in human coronary atheroma: association with the severity of clinical presentation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(7):2035–2042. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boffa M.B., Marcovina S.M., Koschinsky M.L. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for atherosclerosis and thrombosis: mechanistic insights from animal models. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(5):333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sato Y., Kobori S., Sakai M. Lipoprotein(a) induces cell growth in rat peritoneal macrophages through inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta activation. Atherosclerosis. 1996;125(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05829-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grainger D.J. Transforming growth factor beta and atherosclerosis: so far, so good for the protective cytokine hypothesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(3):399–404. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000114567.76772.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kral B.G., Kalyani R.R., Yanek L.R. Relation of plasma lipoprotein(a) to subclinical coronary plaque volumes, three-vessel and left main coronary disease, and severe coronary stenoses in apparently healthy african-Americans with a family history of early-onset coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(5):656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Terres W., Tatsis E., Pfalzer B., Beil F.U., Beisiegel U., Hamm C.W. Rapid angiographic progression of coronary artery disease in patients with elevated lipoprotein(a) Circulation. 1995;91(4):948–950. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tamura A., Watanabe T., Mikuriya Y., Nasu M. Serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations are related to coronary disease progression without new myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995;74(4):365–369. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.4.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morita Y., Himeno H., Yakuwa H., Usui T. Serum lipoprotein(a) level and clinical coronary stenosis progression in patients with myocardial infarction: re-revascularization rate is high in patients with high-Lp(a) Circ J. 2006;70(2):156–162. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Budoff M.J., Hokanson J.E., Nasir K. Progression of coronary artery calcium predicts all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(12):1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Motoyama S., Ito H., Sarai M. Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chironi G., Simon A., Denarie N. Determinants of progression of coronary artery calcifications in asymptomatic men at high cardiovascular risk. Angiology. 2002;53(6):677–683. doi: 10.1177/000331970205300608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matsumoto Y., Daida H., Watanabe Y. High level of lipoprotein(a) is a strong predictor for progression of coronary artery disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1998;5(2):47–53. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.5.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Enas E.A., Mehta J. Malignant coronary artery disease in young Asian Indians: thoughts on pathogenesis, prevention, and therapy. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18(3):131–135. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960180305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hartmann M., von Birgelen C., Mintz G.S. Relation between lipoprotein(a) and fibrinogen and serial intravascular ultrasound plaque progression in left main coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(3):446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arbab-Zadeh A., Fuster V. The risk continuum of atherosclerosis and its implications for defining CHD by coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(22):2467–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Niccoli G., Cin D., Scalone G. Lipoprotein (a) is related to coronary atherosclerotic burden and a vulnerable plaque phenotype in angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Niccoli G., Chin D., Scalone G. Data on the lipoprotein (a), coronary atherosclerotic burden and vulnerable plaque phenotype in angiographic obstructive coronary artery disease. Data Brief. 2016;7:1409–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brunelli C., Spallarossa P., Bertolini S. Lipoprotein (a) is increased in acute coronary syndromes (unstable angina pectoris and myocardial infarction), but it is not predictive of the severity of coronary lesions. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18(9):526–529. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960180909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang J.J., Zhang C.N., Meng Y., Han A.Z., Gong J.B., Li K. Elevated concentrations of oxidized lipoprotein(a) are associated with the presence and severity of acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;408(1-2):79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jubran A., Zetser A., Zafrir B. Lipoprotein(a) screening in young and middle-aged patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiol J. 2018 doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rallidis L.S., Pavlakis G., Foscolou A. High levels of lipoprotein (a) and premature acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2018;269:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sandkamp M., Funke H., Schulte H., Kohler E., Assmann G. Lipoprotein(a) is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction at a young age. Clin Chem. 1990;36(1):20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sandkamp M., Assman G. Lipoprotein (a) in PROCAM participants and young myocardial infarction survivors. In: Scanu A., editor. Lipoprotein (a) Academic Press; San Diego: 1990. pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Isser H.S., Puri V.K., Narain V.S., Saran R.K., Dwivedi S.K., Singh S. Lipoprotein (a) and lipid levels in young patients with myocardial infarction and their first-degree relatives. Indian Heart J. 2001;53(4):463–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sakai Y., Tomobuchi Y., Toyoda Y., Shinozaki M., Hano T., Nishio I. A premenopausal woman presenting with acute myocardial infarction of three different coronary vessels within 1 year: role of lipoprotein(a) Jpn Circ J. 1998;62(11):849–853. doi: 10.1253/jcj.62.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]