Abstract

Background

Multiparametric MRI (mp‐MRI) combined with machine‐aided approaches have shown high accuracy and sensitivity in prostate cancer (PCa) diagnosis. However, radiomics‐based analysis has not been thoroughly compared with Prostate Imaging and Reporting and Data System version 2 (PI‐RADS v2) scores.

Purpose

To develop and validate a radiomics‐based model for differentiating PCa and assessing its aggressiveness compared with PI‐RADS v2 scores.

Study Type

Retrospective.

Population

In all, 182 patients with biopsy‐proven PCa and 199 patients with a biopsy‐proven absence of cancer were enrolled in our study.

Field Strength/Sequence

Conventional and diffusion‐weighted MR images (b values = 0, 1000 sec/mm2) were acquired on a 3.0T MR scanner.

Assessment

A total of 396 features and 385 features were extracted from apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images and T2WI, respectively. A predictive model was constructed for differentiating PCa from non‐PCa and high‐grade from low‐grade PCa. The diagnostic performance of each radiomics‐based model was compared with that of the PI‐RADS v2 scores.

Statistical Tests

A radiomics‐based predictive model was constructed by logistic regression analysis. 70% of the patients were assigned to the training group, and the remaining were assigned to the validation group. The diagnostic efficacy was analyzed with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) in both the training and validation groups.

Results

For PCa versus non‐PCa, the validation model had an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.985, 0.982, and 0.999 with T2WI, ADC, and T2WI&ADC features, respectively. For low‐grade versus high‐grade PCa, the validation model had an AUC of 0.865, 0.888, and 0.93 with T2WI, ADC, and T2WI&ADC features, respectively. PI‐RADS v2 had an AUC of 0.867 in differentiating PCa from non‐PCa and an AUC of 0.763 in differentiating high‐grade from low‐grade PCa.

Data Conclusion

Both the T2WI‐ and ADC‐based radiomics models showed high diagnostic efficacy and outperformed the PI‐RADS v2 scores in distinguishing cancerous vs. noncancerous prostate tissue and high‐grade vs. low‐grade PCa.

Level of Evidence: 3

Technical Efficacy: Stage 2

J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019;49:875–884.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common malignant neoplasms and the second leading cause of cancer‐related death among older males in Western developed countries.1 The incidence is also rising annually in China, and morbidity and mortality have imposed heavy burdens on families and society.2 Thus, the early differentiation and grading of PCa are critical in patient management and the evaluation of long‐term survival.

Serum prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) and digital rectal examination (DRE) are considered the most commonly used PCa screening methods. Although PSA‐based screening is reasonably sensitive, it is nonspecific, leading to a high false‐positive rate and a risk of overtreatment. Among other limitations, DRE cannot usually distinguish between PCa and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).3, 4 Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mp‐MRI) combined with anatomical sequences (T1‐ and T2‐weighted imaging; T1WI and T2WI) and functional sequences (diffusion‐weighted imaging [DWI], dynamic contrast‐enhanced [DCE], magnetic resonance spectroscopy [MRS]) can provide valuable information for PCa differentiation, local staging, and risk classification.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

In 2012, the Prostate Imaging and Reporting and Data System version 1 (PI‐RADS v1) was described to promote standardized reporting criteria for the interpretation of mp‐MRI scans in the assessment of PCa, including clinical indications for prostate mp‐MRI, minimal and optimal imaging acquisition protocols, and a structured category assessment system.11 In 2015, PI‐RADS v2 was released with simplified terminology and mp‐MRI report content. Compared to v1, the new version highlighted the importance of T2WI and DWI sequences, which are more easily obtainable than DCE and MRS.8 Encouraging reports on the role of PI‐RADS v2 in the diagnosis and progress evaluation of PCa have been published and confirmed to improve diagnostic accuracy from 60–90% in the differentiation of PCa.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17

However, in PI‐RADS, subjectivity and interobserver variability has been notable.16, 18 Radiomics,19, 20 the extraction of multiple quantitative imaging features from medical images, has attracted much attention. With automatic feature extraction algorithms, imaging data can be converted to high‐dimensional mineable data and provide valuable information for assessing the diagnosis and prognosis of various disorders.21 Numerous radiomics features combined with machine‐learning approaches could address the above‐mentioned disadvantages of subjectivity and variability, making the interpretation of mp‐MRI more objective and quantitative.21, 22

Currently, machine‐aided approaches have shown high accuracy and sensitivity in discriminating PCa from noncancerous prostate tissues and in differentiating between cancers with different Gleason scores (GSs),23, 24, 25, 26 but a full comparison of the diagnostic performance of radiomics‐based machine‐learning analysis methods and PI‐RADS scores has not been fully researched. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the potential utility of radiomics‐based machine‐learning approaches to differentiate malignant tissue from benign tissue and assess cancer aggressiveness, as well as to compare the diagnostic capabilities based on radiomics versus PI‐RADS v2 scores.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of our hospital, which waived the requirement for written informed consent.

Patient Cohort

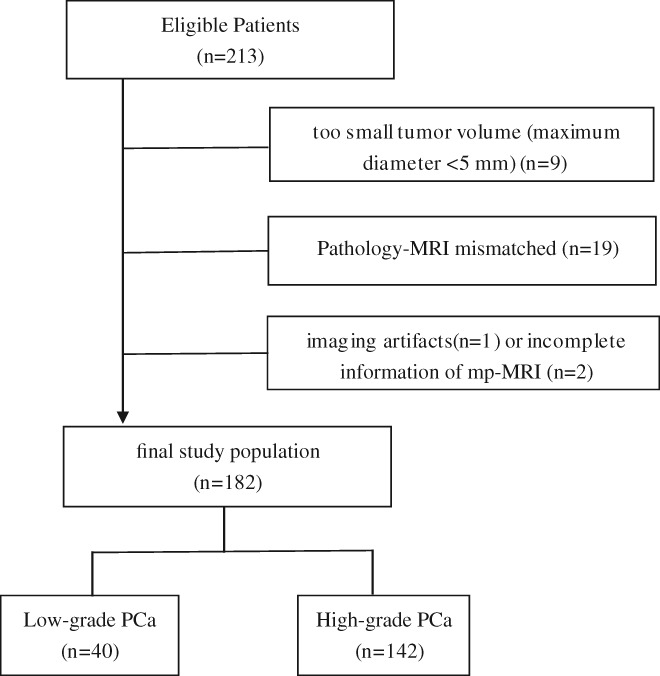

We searched the network information system records between December 2014 and March 2017 in our hospital to identify suitable patients who met the following inclusion criteria: 1) ultrasound‐guided prostate biopsy and pathologically confirmed PCa with GSs; 2) 3T prostate mp‐MRI examination; and 3) no prior prostate surgery, biopsy, radiation therapy, or endocrine therapy before MRI examination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) small tumor volume (maximum diameter <5 mm); ii) pathological biopsy prompted lesions that could hardly be delineated on MRI (those whose cancer location precluded segmentation of normal structures); and iii) the presence of imaging artifacts making the segmentation of cancer lesions impossible or incomplete mp‐MRI information, such as missing images. The final study population consisted of 182 PCa patients and 199 patients without any histological evidence of cancer. Details of patient selection are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection.

MRI Data Acquisition

All scans were performed using a 3.0T MRscanner (Philips Intera Achieva, Best, Netherlands) with a 32‐channel body phased array coil as the receiving coil. Scan sequences included sagittal T2WI, axial T2WI, T1WI, DWI (b values of 0 and 1000 sec/mm2) and DCE. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the details of the imaging sequence parameters, including the sequence type, repetition time / echo time (TR/TE), section thickness, field of view (FOV), and matrix. ADC maps were calculated on a designated workstation.

Region of Interest (ROI) Delineation on T2WI and ADC Images

Only T2WI and ADC images were considered in our study due to the availability and emphasis in PI‐RADS v2. The study workflow was divided into three steps: manual segmentation, ROI merger, and feature extraction.

For consistency between ROIs in both T2WI and ADC images, all depicted ROIs were strictly delineated with the same criteria and visually validated by the same expert. Manual segmentation and ROI merging were carried out in consensus by two radiologists (W.Z. with 15 years of experience and G.W. with 9 years of experience in prostate MRI) using a newly developed software package (Artificial Intelligence Kit, v. 2.0.1, GE Healthcare, China). This software was developed by the GE Healthcare team and can integrate the processes of feature extraction, feature selection, and model establishment.

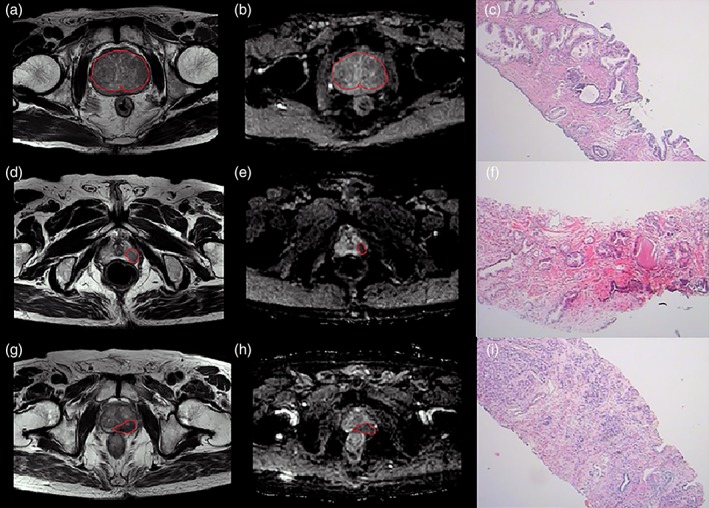

The ROIs were depicted along the boundaries of the lesion layer by layer in reference to the pathological findings of the biopsy (as shown in Fig. 2). Given the importance of heterogeneity analysis, ROIs should include areas of bleeding, necrosis, cystic tissue, and calcification but avoid the urethra, ejaculatory duct, verumontanum, seminal vesicles, and other normal anatomical structures. For multifocal PCa, if all lesions have the same biopsy GS, we outlined the ROI at each level manually until all the lesions were sketched; if the pathological GSs were different, we only selected the highest GS areas for sketching and inducted these patients into the high‐grade group. The lower GS areas were not included in the ROI because the boundaries were often difficult to define clearly on MRI. Thus, our analysis was only focused on the high GS partition, and the PI‐RADS score was also evaluated for this area. Finally, we identified 381 ROIs, 182 for cancerous and 199 for noncancerous tissue.

Figure 2.

ROI delineation of noncancerous tissue and low‐ and high‐grade PCa. (a,d,g: T2WI images; b,e,h: ADC images; c,f,i: pathological images.)

Feature Extraction, Feature Selection, and Model Establishment

Four types of features (first‐order statistics, gradient‐based histogram features, second‐order Haralick textures, and form factor parameters) for a total of 396 features were extracted from ADC images, and 385 features were extracted from T2WI images, as shown in Supplementary Table 2. The whole process of feature extraction was performed using Artificial Intelligence Kit software.

Not all of the extracted features would be useful for differential diagnosis; thus, we adopted a series of methods for dimensionality reduction and feature selection to identify the optimal set of features to differentiate cancer vs. normal prostate tissues as well as PCa with different GSs. To reduce overfitting or selection bias in our radiomics model, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kruskal–Wallis test, univariate logistic, and least absolute shrinkage selection operator (LASSO) were used to explore the informative features that correlated best with histopathology; Spearman was defined to reduce the redundancy of the features, in which features with high correlation were removed; random forest was applied to sort the features based on their importance to the classifier, which helped us to pick the most important features.27, 28, 29 At last, the 10 most significant features were investigated to construct a radiomics model. If feature numbers were less than 10 after Spearman analysis, random forest was not applied. The number of features after each feature selection step is shown in Supplementary Table 3.

To distinguish cancerous from normal prostate tissue, the patients were stochastically divided into two groups: 70% of the patients were assigned to the training group (n = 266) for establishing the predictive model, and the remaining patients were assigned to the validation group (n = 115) for evaluating the predictive model. In distinguishing low‐grade (GS ≤6) from intermediate/high‐grade (GS ≥7) tumors, the number of patients with low‐grade PCa was much smaller than the number of patients with high‐grade PCa, and the sample imbalance would have an adverse impact on the performance of a classifier, resulting in a high accuracy but low specificity and sensitivity. Thus, we used the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) to generate a sample from the joint weighting of multiparametric features. Similarly, 70% of the patients were assigned to the training group (n = 56), and the remaining patients were assigned to the validation group (n = 28). A predictive model was constructed from selected features in the training group using a generalized linear model with logistic regression for classification analysis based on the features extracted from ADC and T2WI images separately and in combination.

PI‐RADS Evaluation

Three radiologists (with 10, 5, and 3 years of experience in prostate MRI diagnosis; T.C., J.M., and Y.G., respectively) were responsible for image interpretation but did not participate in the previous process of ROI delineation. During the image evaluation, the investigators were blinded to all clinicopathological information and scored in strict accordance with the PI‐RADS v2 scoring criteria (on a scale of 1–5) independently.30

Statistical Analysis

Kendall's W test was performed to calculate the interreader concordance coefficient of the PI‐RADS scores obtained by the three radiologists.

The validation data were used to verify the diagnostic efficacy of the predictive models, and the differences between the predictive models vs. PI‐RADS v2 scores in identifying benign vs. malignant PCa and low‐ vs. intermediate/high‐grade PCa were analyzed with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. With the maximum Youden index as the critical value, the diagnostic sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), and overall accuracy (ACC) were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics).

Results

Patient Characteristics

The clinical and tumor characteristics of the selected patients are presented in Table 1. A total of 182 patients with cancer foci and 199 patients without any histological evidence of cancer were identified.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Patient Cohort

| PCa | Non‐PCa | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 182 | 199 |

| Mean age (y) [range] | 74 [56–90] | 68 [55–88] |

| PSA (ng/ml) | ||

| PSA≤10 | 31 | 109 |

| 10<PSA≤20 | 34 | 57 |

| PSA>20 | 117 | 33 |

| Gleason score (n, %) | ||

| 6 | 40 (22%) | — |

| 7 | 62 (34%) | — |

| 8 | 38 (21%) | — |

| 9 | 32 (18%) | — |

| 10 | 10 (5%) | — |

PCa: prostate cancer; PSA: prostate‐specific antigen.

The overall interreader consistency was good for PI‐RADS scores among the three readers (Kendall's W = 0.956, P < 0.001), as shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Feature Selection and Radiomics Model Establishment

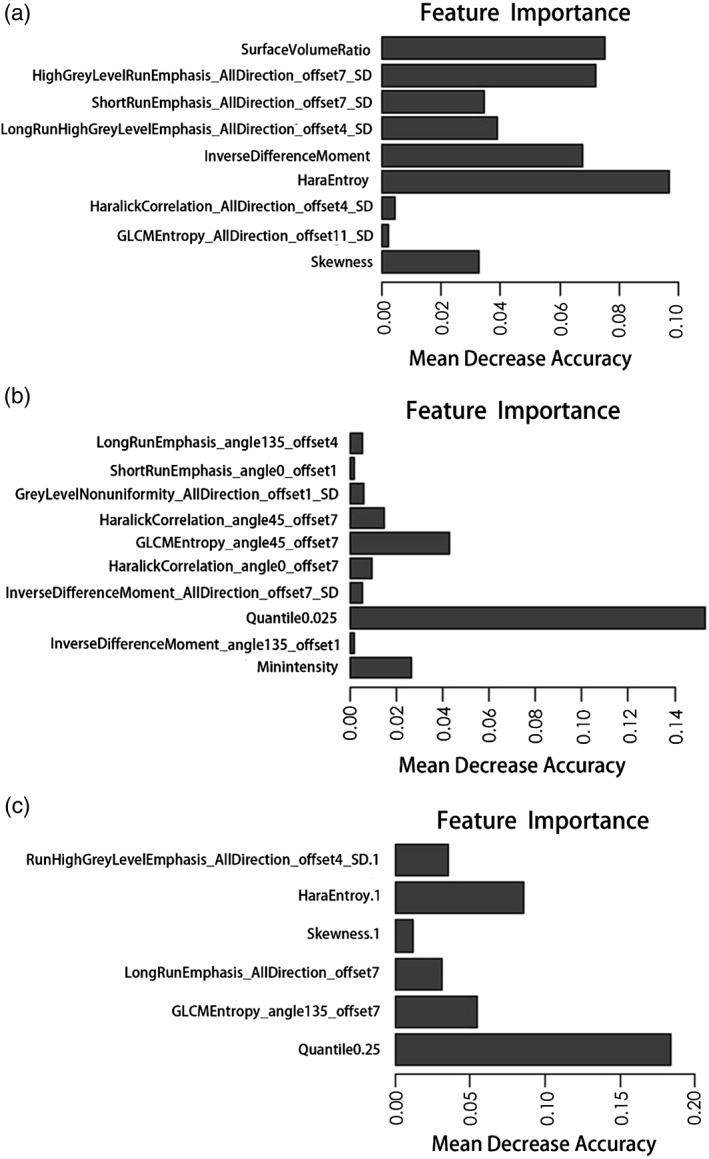

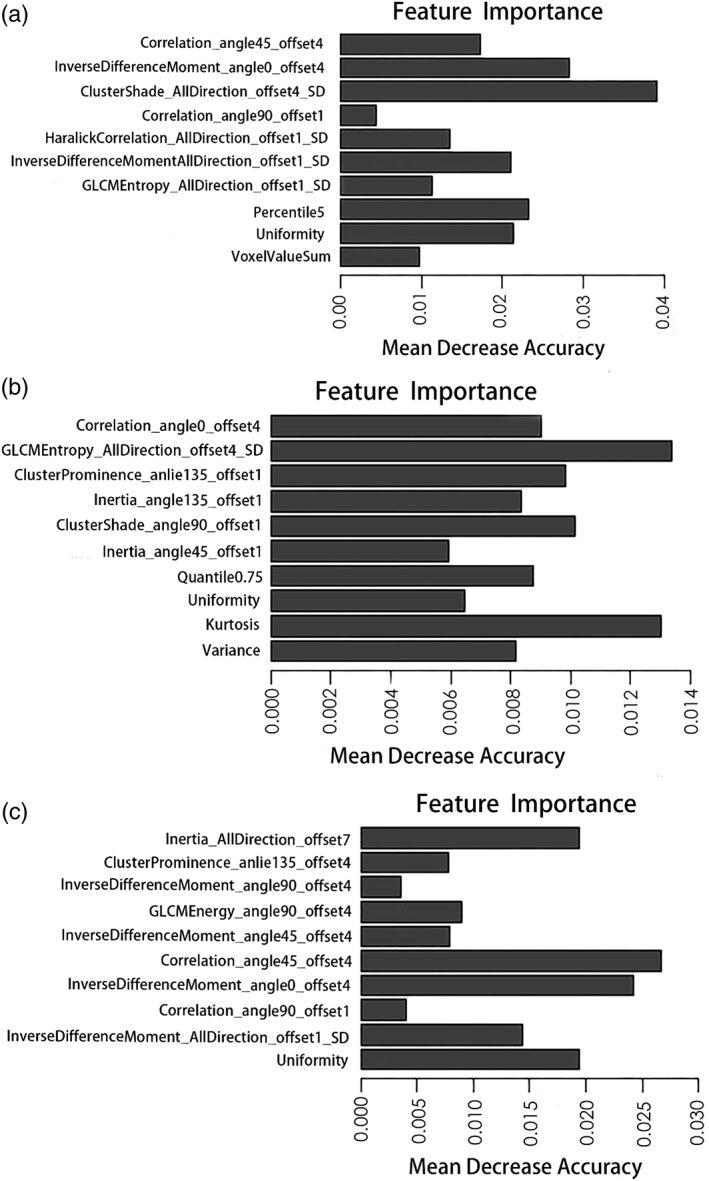

We selected nine features from T2WI images, ten features from ADC images, and six features from T2WI and ADC images combined to classify candidates as either cancerous or noncancerous, as well as ten features from T2WI, ADC, and T2WI&ADC images for tumor grading. The relative feature importance computed by the random forest of all extracted features is shown in Figs. 3, 4. The logistic regression model was established by incorporating the 1) T2WI features, 2) ADC features, 3) T2WI&ADC features, and 4) PI‐RADS scores.

Figure 3.

The importance of features extracted from T2WI, ADC, and T2WI&ADC images to distinguish PCa from noncancerous patients is shown in A–C, respectively.

Figure 4.

The importance of features extracted from T2WI, ADC, and T2WI&ADC images to distinguish high‐ from low‐grade PCa is shown in A–C, respectively.

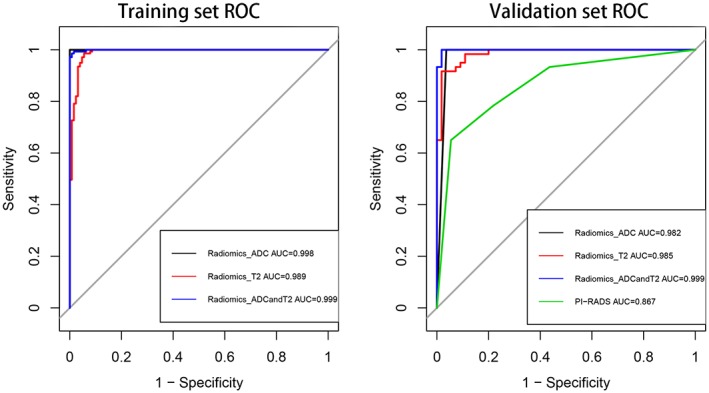

PCa vs. Non‐PCa Classification

The efficacy of using the features extracted from T2WI and ADC images, both individually and combined, in the differentiation of PCa from noncancerous tissue is shown in Table 2 and Fig. 5. In the training group, the AUC, accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity were 0.989, 0.966, 0.945, and 0.986 based on the T2WI model, 0.998, 0.989, 0.984, and 0.993 based on the ADC model, and 0.999, 0.989, 0.992, and 0.986 based on the T2WI&ADC model, respectively. In the validation group, the AUC, accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity were 0.985, 0.948, 0.982, and 0.917 based on the T2WI model, 0.982, 0.983, 0.964, and 1.000 based on the ADC model, and 0.999, 0.991, 0.982, and 1.000 based on the T2WI&ADC model, respectively. After combining all the features together, the AUC increased to 0.999, slightly higher than that for T2WI or ADC features alone. Comparing the differences in the performance of the radiomics‐based model and PI‐RADS scores, each radiomics‐based model outperformed the PI‐RADS scores, as shown in Fig. 5.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Results for PCa vs. Non‐PCa Classification in the Training and Validation Groups

| Training group | Validation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | T2WI | ADC | T2WI&ADC | T2WI | ADC | T2WI&ADC |

| AUC | 0.989 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.985 | 0.982 | 0.999 |

| ACC | 0.966 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.948 | 0.983 | 0.991 |

| SPE | 0.945 | 0.984 | 0.992 | 0.982 | 0.964 | 0.982 |

| SEN | 0.986 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.917 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

AUC: area under the curve; ACC: accuracy; SPE: specificity; SEN: sensitivity.

Figure 5.

ROC curves for radiomics‐based ADC, T2WI, and ADC&T2WI model and PI‐RADS score performance in distinguishing PCa vs. non‐PCa in the training and validation groups, respectively.

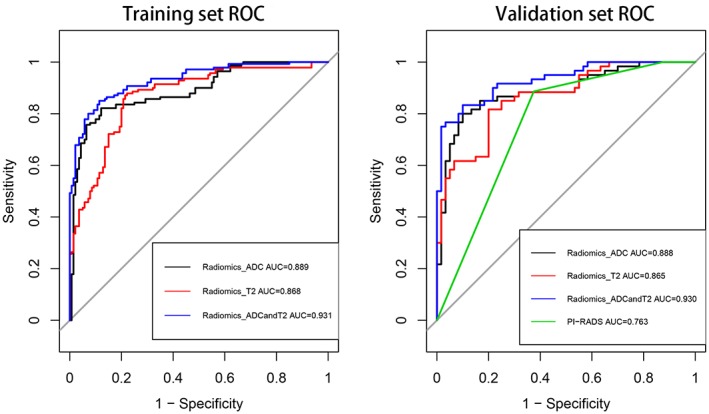

Low‐Grade (GS ≤6) vs. High‐Grade (GS >7) PCa Classification

The performance of the radiomics model without any sample augmentation and with sample augmentation by the SMOTE method is shown in Tables 3 and 4 for the training and validation groups, respectively. Without sample augmentation, the AUC, accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity of the T2WI, ADC, T2WI&ADC classifiers was relatively high in the training group but low in the validation group. When using samples augmented by the SMOTE method, the performance of the classifiers in the validation group improved significantly. The accuracy of classifiers for differentiating low‐grade from high‐grade PCa improved from 0.618 without sample augmentation to 0.808 with SMOTE sampling on T2WI, from 0.673 to 0.850 on ADC, and from 0.709 to 0.867 on T2WI&ADC. The Youden index improved from 0.512 to 0.617 on T2WI, from 0.281 to 0.700 on ADC, and from 0.507 to 0.730 on T2WI&ADC with oversampling. In addition, when combining all the features of T2WI and ADC together, the AUC value increased to 0.930, which is higher than that of T2WI (0.865) or ADC (0.887) alone. Comparing the differences in the performance of the radiomics‐based model and PI‐RADS scores, the performance of the PI‐RADS score classifiers, which have an AUC of 0.763, was much worse than that of the radiomics feature classifiers, as shown in Fig. 6.

Table 3.

Diagnostic Results for GS 6 vs. GS≥7 PCa Classification in the Training Group With and Without Oversampling

| Method | 40/142 samples (no augmentation) | 200/200 samples (SMOTE augmentation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | T2WI | ADC | T2WI&ADC | T2WI | ADC | T2WI&ADC |

| AUC | 0.869 | 0.850 | 0.921 | 0.867 | 0.889 | 0.931 |

| ACC | 0.811 | 0.748 | 0.858 | 0.829 | 0.850 | 0.868 |

| SPE | 0.857 | 0.893 | 0.929 | 0.779 | 0.879 | 0.886 |

| SEN | 0.798 | 0.707 | 0.838 | 0.879 | 0.821 | 0.850 |

| Youden index | 0.655 | 0.600 | 0.767 | 0.658 | 0.700 | 0.736 |

Table 4.

Diagnostic Results for GS 6 vs. GS≥7 PCa Classification in the Validation Group With and Without Oversampling

| Method | 40/142 samples (no augmentation) | 200/200 samples (SMOTE augmentation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | T2WI | ADC | T2WI&ADC | T2WI | ADC | T2WI&ADC |

| AUC | 0.682 | 0.609 | 0.777 | 0.865 | 0.887 | 0.930 |

| ACC | 0.618 | 0.673 | 0.709 | 0.808 | 0.850 | 0.867 |

| SPE | 1.000 | 0.583 | 0.833 | 0.800 | 0.900 | 0.900 |

| SEN | 0.512 | 0.698 | 0.674 | 0.817 | 0.800 | 0.833 |

| Youden index | 0.512 | 0.281 | 0.507 | 0.617 | 0.700 | 0.730 |

Figure 6.

ROC curves for radiomics‐based ADC, T2WI, and ADC&T2WI model and PI‐RADS score performance in distinguishing GS 6 vs. GS ≥7 PCa in the training and validation groups, respectively.

Discussion

In this study we developed a radiomics‐based machine‐learning model for PCa differentiation and aggressiveness assessment and compared its diagnostic efficacy with that of PI‐RADS v2 scores. By extracting many quantitative image features and efficiently selecting features, T2WI and ADC radiomics models based on logistic regression were established. When the models were trained with validated data, they retained high performance in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC for achieving the correct diagnosis and aggressiveness assessment and even outperformed the PI‐RADS v2 scores, illustrating the power of the radiomics‐based machine‐learning models in highly effective classification.

A number of studies have used radiomics analysis to automate PCa diagnosis and risk stratification.19, 20 Gao et al31 utilized an artificial neural network (ANN) classifier to detect PCa using quantitative features extracted from DWI. The diagnostic prediction reached high accuracies (89.7% for the peripheral zone [PZ] and 91% for the transition zone [TZ]) and specificity (94.8% for the PZ and 94.1% for the TZ) while maintaining acceptable sensitivity (80.4% for the PZ and 82.7% for the TZ). Sidhu et al26 derived histogram parameters from ADC, T2WI, and early postcontrast T1WI to detect PCa in the TZ, and the combination of kurtosis and entropy could reach an AUC of 86%. Cameron et al32 presented a quantitative radiomics model using morphology, asymmetry, physiology, and size (MRPS) features to detect PCa and showed 87% accuracy, 86% sensitivity, and 88% specificity. Duda et al25 reported that the best classification accuracies were 81.00% for T1WI, 97.39% for T2WI, and 96.88% for DWI.

In general, T2WI and ADC are the most common sequences selected by investigators for radiomics research.33, 34, 35 In addition, the PI‐RADS v2 scoring system increases the diagnosis weight of T2WI and ADC and reduces the diagnosis weight of DCE.8 Therefore, we chose to derive radiomics features from T2WI and ADC only for this study, and our results show that the diagnostic performance of the radiomics‐based model to separate cancerous and noncancerous tissues in the prostate is better than that previously reported.33, 34, 35 The diagnostic efficacy of the radiomics models based on either sequence (T2WI or ADC) alone reached a very high level, and the diagnostic efficacy of the comprehensive sequence‐based radiomics model slightly increased. Possible explanations may be as follows. First, compared to established radiomics models,33, 34, 35 our study applied improved feature selection. We adopted a variety of approaches to filter features gradually, which guaranteed that all the selected features were valuable for the classification. Furthermore, the patients themselves incorporated in our study differed significantly, which means standard patient population with prostate cancer, and that may lead to the high diagnostic efficacy required for further verification. In this way, we believe that the diagnostic efficacy of both the T2WI‐ and ADC‐based radiomics models can reach high levels and that more sophisticated sequences are not so necessary in some patients, which would help to simplify our scanning solution.

PCa of different pathological levels exhibits differences in internal cellular components, fluid contents, collagen levels, and fibromuscular stroma, among other features. High‐grade PCa is poorly differentiated and characterized by high cellularity and decreased extracellular space. Low‐grade tumors have at least some remaining glandular structures, which preserve some intercellular space.35, 36 These differences in histopathological features could be reflected through quantitative analysis by radiomics approaches. Many studies have shown that texture parameters extracted from T2WI and ADC images can distinguish high‐ from low‐grade PCa with a diagnostic level reaching more than 80%.23, 37, 38 However, these research methods only extract a few texture features, and the feedback information is relatively limited. In this study, we not only extracted a large number of radiomics signatures but also screened the most validated features to establish a model for assessing the diagnostic efficacy in classifying high‐ and low‐grade PCa. It must be explained that, due to the unequal number of high‐ and low‐grade patients, we adopted the SMOTE method, which generates samples from the joint weighting of features for oversampling to balance samples. Without sample augmentation, the established model would have some bias in classification. This method was also certified by Fehr et al24; their study showed that random switching frequency‐space vector modulation (RSF‐SVM) with SMOTE achieves the highest accuracy for classifying GS 6 versus GS ≥7, and GS 3 + 4 versus GS 4 + 3 PCa. Accordingly, our study shows that the performance of the radiomics‐based model in the validation group was significantly improved with SMOTE sample augmentation.

The radiomics‐based models with T2WI, ADC, or T2WI&ADC features outperformed the PI‐RADS scores for PCa differentiation and aggressiveness evaluation, which is consistent with previous studies. Gao et al31 extracted several texture features from DWI and compared the computer‐aided diagnosis model with DWI scores from PI‐RADS v2; the CAD‐predicted AUCs were higher than the AUCs of the DWI scores. Wang et al39 also indicated that a radiomics‐based machine‐learning approach can help to improve the predictive performance of PI‐RADS scores. The interpretation of the PI‐RADS score according to each image feature for PCa diagnosis is subjective and highly reader‐dependent, while our radiomics‐based model is quantitative and relatively objective and achieves a higher diagnostic efficiency than PI‐RADS scores. These encouraging results suggest that radiomics approaches are promising techniques for optimizing the existing routine workflow for PCa diagnosis and aggressiveness evaluation, making it more reliable and reproducible.

There are several limitations in our study. First, all pathological results were biopsy‐proven and lacked further validation with radical prostatectomy specimens. Histological‐radiological matching was performed by experienced radiologists based on the biopsy site and MR images, which was an inevitable source of bias. Nevertheless, we manually segmented and delineated ROIs with two radiologists in consensus, trying our best to reduce the deviation. Furthermore, our study did not distinguish between peripheral and transitional PCa because, in some cases, PCa occurred in both zones. Further research should include a larger study population and treat peripheral and transitional PCa differently. Additionally, although our research extracted partial data to validate the radiomics‐based models, other external validation cohorts should also be included to test the reproducibility in future studies.

In conclusion, a combined approach of radiomics‐based feature extraction and machine learning was developed in this study to differentiate malignant from benign prostate tissue and assess PCa aggressiveness, and the diagnostic capability of the radiomics‐based models and PI‐RADS scores was compared. The diagnostic performance of our T2WI or ADC radiomics‐based models was high, and the comprehensive diagnostic efficacy was slightly increased. The efficacy of the radiomics‐based model was better than that of PI‐RADS scores.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgment

Contract grant sponsor: Suzhou Science and Technology Development Plan; Contract grant number: SS201534; Contract grant sponsor: Advantageous Clinical Discipline Group of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University; Contract grant number: XKQ2015009. The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Wenlu Zhao, Email: wenluzhao81@163.com.

Junkang Shen, Email: shenjunkang@suda.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistic, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate‐cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gupta RT, Kauffman CR, Polascik TJ, et al. The state of prostate MRI in 2013. Oncology 2013;27:262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yakar D, Debats OA, Bomers JG, et al. Predictive value of MRI in the localization, staging, volume estimation, assessment of aggressiveness, and guidance of radiotherapy and biopsies in prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012;35:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soylu FN, Peng Y, Jiang Y, et al. Seminal vesicle invasion in prostate cancer: Evaluation by using multiparametric endorectal MR imaging. Radiology 2013;267:797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Q, Li H, Yan X, et al. Histogram analysis of diffusion kurtosis magnetic resonance imaging in differentiation of pathologic Gleason grade of prostate cancer. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Invest 2015;33:337.e15–337.e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park SY, Oh YT, Jung DC, et al. Prediction of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy with PI‐RADS version 2 in prostate cancers: Initial results. Eur Radiol 2016;26:2502–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moradi M, Salcudean SE, Chang SD, et al. Multiparametric MRI maps for detection and grading of dominant prostate tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014;191:e592–e592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turkbey B, Merino MJ, Gallardo EC, et al. Comparison of endorectal coil and nonendorectal coil T2W and diffusion‐weighted MRI at 3 Tesla for localizing prostate cancer: Correlation with whole‐mount histopathology. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013;39:1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, et al. European Society of Urogenital Radiology. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol 2012;22:746–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park SY, Shin SJ, Jung DC, et al. PI‐RADS version 2: Preoperative role in the detection of normal‐sized pelvic lymph node metastasis in prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol 2017;91:22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao C, Gao G, Fang D, et al. The efficiency of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) using PI‐RADS version 2 in the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer. Clin Imaging 2016;40:885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jordan EJ, Fiske C, Zagoria RJ, et al. Evaluating the performance of PI‐RADS v2 in the non‐academic setting. Abdom Radiol 2017;42:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Auer T, Edlinger M, Bektic J, et al. Performance of PI‐RADS version 1 versus version 2 regarding the relation with histopathological results. World J Urol 2017;35:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasel‐Seibert M, Lehmann T, Aschenbach R, et al. Assessment of PI‐RADS v2 for the detection of prostate cancer. Eur J Radiol 2016;85:726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spektor M, Mathur M, Weinreb JC. Standards for MRI reporting—the evolution to PI‐RADS v 2.0. Transl Androl Urol 2017;6:355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosenkrantz A B, Ginocchio L A, Cornfeld D, et al. Interobserver Reproducibility of the PI‐RADS Version 2 Lexicon: A multicenter study of six experienced prostate radiologists. Radiology 2016;280:152542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 2016;278:563–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, et al. Radiomics: The process and the challenges. Magn Reson Imaging 2012;30:1234–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lambin P, Rios‐Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, et al. Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang S, Burtt K, Turkbey B, et al. Computer aided‐diagnosis of prostate cancer on multiparametric MRI: A technical review of current research. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:789561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wibmer A, Hricak H, Gondo T, et al. Haralick texture analysis of prostate MRI: Utility for differentiating non‐cancerous prostate from prostate cancer and differentiating prostate cancers with different Gleason scores. Eur Radiol 2015;25:2840–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fehr D, Veeraraghavan H, Wibmer A, et al. Automatic classification of prostate cancer Gleason scores from multiparametric magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:6265–6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duda D, Kretowski M, Mathieu R, et al. Multi‐sequence texture analysis in classification of in vivo MR images of the prostate. Biocybernet Biomed Eng 2016;36:537–552. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sidhu HS, Benigno S, Ganeshan B, et al. Textural analysis of multiparametric MRI detects transition zone prostate cancer. Eur Radiol 2017;27:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Langley P. Selection of nt features in machine learning. Procaaai Fall Sympon Relev 1994;140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Balagurunathan Y, Gu Y, Wang H, et al. Reproducibility and prognosis of quantitative features extracted from CT images. Transl Oncol 2014;7:72–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bickel PJ, Ritov YA, Tsybakov AB. Simultaneous analysis of Lasso and Dantzig selector. Ann Stat 2009;37:1705–1732. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, et al. PI‐RADS Prostate Imaging — Reporting and Data System: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol 2016;69:16–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gao G, Wang C, Zhang X, et al. Quantitative analysis of diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance images: Differentiation between prostate cancer and normal tissue based on a computer‐aided diagnosis system. Sci China Life Sci 2017;60:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cameron A, Khalvati F, Haider MA, et al. MAPS: A quantitative radiomics approach for prostate cancer detection. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2016;63:1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khalvati F, Wong A, Haider MA. Automated prostate cancer detection via comprehensive multi‐parametric magnetic resonance imaging texture feature models. BMC Med Imaging 2015;15:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jin TK, Sheng X, Wood BJ, et al. Automated prostate cancer detection using T2‐weighted and high‐b‐value diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Med Phys 2015;42:2368–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hegde JV, Mulkern RV, Panych LP, et al. Multiparametric MRI of prostate cancer: An update on state‐of‐the‐art techniques and their performance in detecting and localizing prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013;37:1035–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Donati OF, Mazaheri Y, Afaq A, et al. Prostate cancer aggressiveness: Assessment with whole‐lesion histogram analysis of the apparent diffusion coefficient. Radiology 2014;271:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vignati A, Mazzetti S, Giannini V, et al. Texture features on T2‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging: New potential biomarkers for prostate cancer aggressiveness. Phys Med Biol 2015;60:2685–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nketiah G, Elschot M, Kim E, et al. T2‐weighted MRI‐derived textural features reflect prostate cancer aggressiveness: Preliminary results. Eur Radiol 2016;27:3050–3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang J, Wu CJ, Bao ML, et al. Machine learning‐based analysis of MR radiomics can help to improve the diagnostic performance of PI‐RADS v2 in clinically relevant prostate cancer. Eur Radiol 2017;27:4082–4090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information