The treatment of progressive high-grade glioma remains a challenge.1 The phase II REGOMA trial in patients with a first glioblastoma progression revealed a significant improvement in median overall survival (mOS) for regorafenib, with 7.4 (5.8–12.0) versus 5.6 (4.7–7.3) months in the lomustine arm.2

We present a retrospective bicentric cohort of 24 adult patients (median age 54, range 33–70; Karnofsky performance score [KPS] 80–100% n = 9; 70% n = 9; 50–60% n = 6) with advanced high-grade gliomas (19 glioblastoma isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 wildtype, 1 diffuse midline glioma, 1 anaplastic oligodendroglioma, 1 anaplastic astrocytoma, 2 glioblastoma IDH mutation; 6 O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) methylated, 17 MGMT unmethylated, 1 unknown MGMT status). The ethics committees of the Universities of Bonn and Tübingen approved this analysis. All 24 patients were treated with regorafenib (80–160 mg daily, 21 days on, 7 days off), mostly at later stages of the disease (3 first relapse, 9 second relapse, 12 third to seventh relapse). As first-line treatment 23/24 (96%) had alkylating chemotherapy (21/23 with radiation therapy) and 1 patient had radiotherapy only. Further prior systemic treatments for progressive disease included lomustine (21), temozolomide (7), bevacizumab (5), and an experimental IDH inhibitor (1).

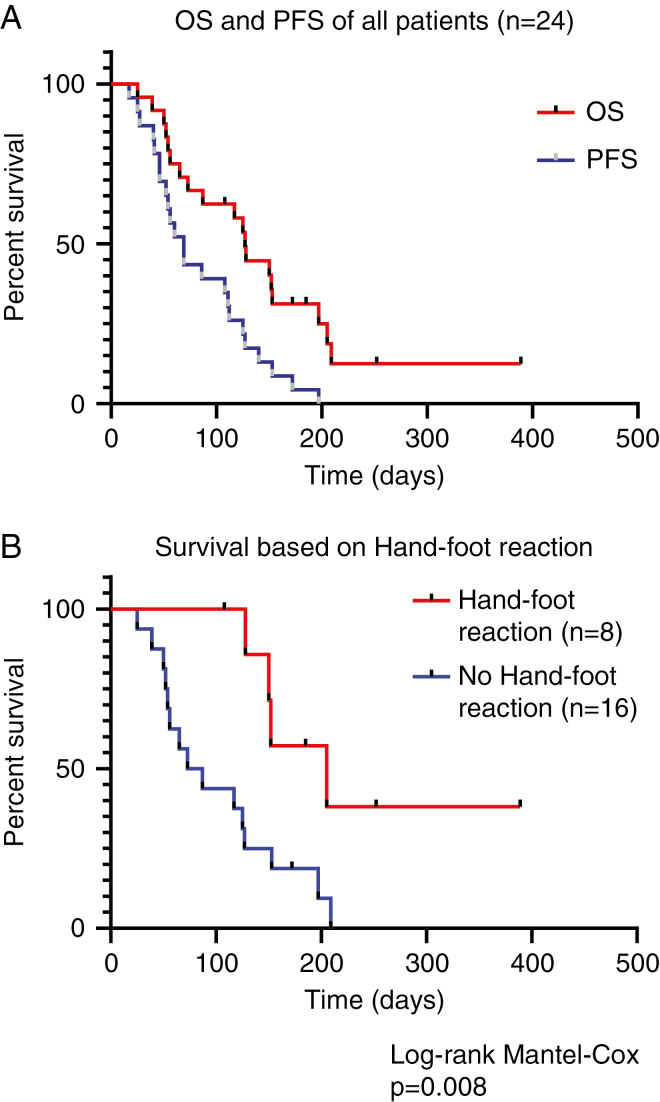

The first MRI 6–12 weeks after regorafenib initiation, which was obtainable in 18/24 patients (75%), showed a partial response according to RANO in 3 patients (13%) and stable disease in 3 patients (13%). The median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 2.1 months. The mOS after regorafenib onset was 4.1 months in the whole cohort and 4.2 months in the group of 19 patients with IDH wildtype tumors (Fig. 1A). The most common adverse events included dermatological events, mainly hand-foot reaction (HFR) in 8/24 (30%) patients and OS was significantly longer in patients with HFR (mOS 6.7 mo versus mOS 2.6 mo, P = 0.008 log-rank test) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Clinical outcome in a retrospective bicentric cohort of 24 patients with advanced high-grade gliomas. (A) Kaplan–Meier plot showing overall survival (OS, red curve) and progression-free survival (PFS, blue curve) of all 24 patients. (B) Kaplan–Meier plot showing overall survival of patients with hand-foot reaction (HFR; red) compared with patients who did not experience HFR (blue).

Taken together, the mPFS of 2.1 months in our bicentric cohort was similar to REGOMA2 (2.0 mo). Yet, mOS was longer in REGOMA (7.4 mo) than in our present cohort (4.1 mo). This certainly reflects that our cohort included patients at a later stage of the disease. The population of the present cohort is rather comparable with retrospective data for bevacizumab in patients with third progression of glioblastoma and a KPS <80% leading to mOS of 3.6 months.3

Considering the results of REGOMA and our present cohort, a randomized phase III trial is certainly warranted, and this next step will be accomplished by a regorafenib arm in the network Adaptive Global Innovative Learning Environment for Glioblastoma (GBM AGILE). The necessity of a phase III trial is further supported by the history of bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma, where a randomized phase II trial (BELOB)4 suggested a benefit for the combination of bevacizumab and lomustine. Yet, this was not confirmed in the large phase III trial.5

Our regorafenib cohort includes an observation that may help for clinical patient stratification: the occurrence of HFR (30% in our cohort, 32% in REGOMA) was associated with a better clinical outcome (Fig. 1B). This parallels observations in colorectal cancer6 and could also serve as a clinical decision tool for the continuation of regorafenib treatment in glioblastoma patients.

In conclusion, the upcoming regorafenib arm in GBM Agile will further define the role of regorafenib in glioblastoma. Until then, and considering the lack of other convincing medical treatment approaches for advanced malignant glioma, regorafenib may be a treatment option albeit not a highly efficient one.

Funding

Funding was not applicable.

Conflict of interest statement.

Dr Bender received travel support by Bayer Vital. Dr Gepfner-Tuma reports speaker’s fees from Novocure and a grant from Medac. Dr Herrlinger reports grants and personal fees from Roche, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Medac, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Novocure, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Daichii Sankyo, personal fees from Riemser, personal fees from Noxxon, personal fees from Abbvie, personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Dr Hirsch reports grants from Novocure and Medac. Dr Schäfer received honoraria and travel fees from Roche. Dr Tabatabai reports personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from Novocure, personal fees from Medac, grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants from Novocure, grants from Roche Diagnostics, grants from Medac. No other authors had conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Weller M, van den Bent M, Tonn JC, et al. ; European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) Task Force on Gliomas European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):e315–e329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lombardi G, De Salvo GL, Brandes AA, et al. Regorafenib compared with lomustine in patients with relapsed glioblastoma (REGOMA): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schaub C, Tichy J, Schäfer N, et al. Prognostic factors in recurrent glioblastoma patients treated with bevacizumab. J Neurooncol. 2016;129(1):93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taal W, Oosterkamp HM, Walenkamp AM, et al. Single-agent bevacizumab or lomustine versus a combination of bevacizumab plus lomustine in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (BELOB trial): a randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1954–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. ; CORRECT Study Group Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]