Abstract

Daily compensable cold exposure in humans reduces shivering by ~20% without changing total heat production, partly by increasing brown adipose tissue thermogenic capacity and activity. Although acclimation and acclimatization studies have long suggested that daily reductions in core temperature are essential to elicit significant metabolic changes in response to repeated cold exposure, this has never directly been demonstrated. The aim of the present study is to determine whether daily cold-water immersion, resulting in a significant fall in core temperature, can further reduce shivering intensity during mild acute cold exposure. Seven men underwent 1 h of daily cold-water immersion (14°C) for seven consecutive days. Immediately before and following the acclimation protocol, participants underwent a mild cold exposure using a novel skin temperature clamping cold exposure protocol to elicit the same thermogenic rate between trials. Metabolic heat production, shivering intensity, muscle recruitment pattern, and thermal sensation were measured throughout these experimental sessions. Uncompensable cold acclimation reduced total shivering intensity by 36% (P = 0.003), without affecting whole body heat production, double what was previously shown from a 4-wk mild acclimation. This implies that nonshivering thermogenesis increased to supplement the reduction in the thermogenic contribution of shivering. As fuel selection did not change following the 7-day cold acclimation, we suggest that the nonshivering mechanism recruited must rely on a similar fuel mixture to produce this heat. The more significant reductions in shivering intensity compared with a longer mild cold acclimation suggest important differential metabolic responses, resulting from an uncompensable compared with compensable cold acclimation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Several decades of research have been dedicated to reducing the presence of shivering during cold exposure. The present study aims to determine whether as little as seven consecutive days of cold-water immersion is sufficient to reduce shivering and increase nonshivering thermogenesis. We provide evidence that whole body nonshivering thermogenesis can be increased to offset a reduction in shivering activity to maintain endogenous heat production. This demonstrates that short, but intense cold stimulation can elicit rapid metabolic changes in humans, thereby improving our comfort and ability to perform various motor tasks in the cold. Further research is required to determine the nonshivering processes that are upregulated within this short time period.

Keywords: cold acclimation, cold-water immersion, energy metabolism, nonshivering thermogenesis, shivering thermogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Humans exposed to a cold environment rely on the recruitment of heat-conserving and heat-producing cold-defense responses to limit and counteract the heat lost to the surrounding environment. In nonexercising humans, metabolic heat production () is sustained by the combined activation of nonshivering thermogenesis (NST) and shivering thermogenesis (ST). Both brown adipose tissue (BAT) (22, 29) and skeletal muscle proton leak (3, 31) have been identified as significant contributors to NST during acute cold exposure in lean, young, unacclimated individuals. However, ST remains the predominant form of heat production in cold-exposed adult humans. The recruitment of ST, in particular, can affect thermal comfort and work performance in the cold by impairing gross and fine neuromuscular performance and coordination (9, 21), ultimately impacting the odds of survival. Consequently, over several decades, investigators have attempted to identify a cold acclimation protocol that could help elicit significant changes in thermoregulatory, metabolic, and neuromuscular responses as a means of improving thermal comfort and work performance in the cold (9, 32).

Despite the breadth of research examining the effects of repeated cold exposure on the thermoregulatory responses to an acute cold, only two studies have quantified the effects of cold acclimation on changes in ST in young healthy humans. In 1961, Davis showed that 31 days of cold air exposure (~12°C, 8 h/day) resulted in an ~80% reduction in ST and ~15% reduction in whole body in healthy men previously acclimatized to summer conditions (seasonal average of ~20–30°C (10). More than five decades later, Blondin et al. (3) showed that 4 wk of daily compensable cold exposure in unacclimatized men using a liquid conditioned suit (LCS) (for 2 h/day at 10°C, 5 days/wk) was sufficient to elicit a ~20% decrease in ST response for the same given . In addition, by combining isotopic and nuclear imaging methods in these same individuals, the authors also showed that BAT volume and thermogenic capacity increased following cold acclimation by 45% and 182%, respectively, and concomitantly reduced skeletal muscle proton leak (3). Although these results are promising as a means of improving cold tolerance, identifying a cold acclimation protocol that can shorten the time required to increase the relative contribution of NST to total but reduce that of ST would be particularly valuable in this field of physiology.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether a short-duration, high-intensity cold acclimation would reduce the contribution of ST to total for the same absolute cold stress. More specifically, we quantified whether seven consecutive days of 14°C water immersion for 1 h, resulting in a maximum of 2°C decrease in core temperature, would result in a significant decrease in ST and improve thermal sensation between a preaclimation compared with a postacclimation acute cold exposure at the same given . In 1996, Young (32) suggested that the greatest metabolic effects resulting from repeated cold exposure would require a sufficiently uncompensable cold exposure stimulus that would result in a decrease in core temperature. By using such a cold acclimation approach, we predict will result in a greater cold-induced stimulation of nonshivering thermogenic pathways and reduce the contribution of shivering to total heat production, compared with what was previously shown from a compensable cold acclimation protocol (3).

METHODS

Participants

Seven healthy, nonacclimatized adult males between the ages of 20 and 29 yr old volunteered for this study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Health Sciences Ethics Committee of the University of Ottawa. All participants filled out the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q+) and gave written informed consent before their participation. Individuals that were cold or heat acclimatized, taking any medications or dietary supplements, or who had known metabolic, respiratory, or cardiovascular disease were excluded.

Body height, mass, surface area, and density, as well as maximal oxygen consumption (V̇o2max) were measured during the screening session. Body height was measured using an eye-level physician stadiometer (model 2391; Detecto Scale Company, Webb City, MO), while body mass was measured using a digital weight scale (model CBY150X; Mettler Toledo) with a high-performance weighing terminal (model IND560; Mettler Toledo). Measurements of body height and mass were subsequently used to calculate body surface area (11). Body density was measured using the hydrostatic weighing technique and used to estimate body fat percentage (27). Maximal oxygen consumption (V̇o2max) was determined by incremental treadmill exercise to volitional fatigue. Breath-by-breath oxygen consumption was measured by an automated indirect calorimetry system (Medgraphics Ultima, Medical Graphics, St. Paul, MN), and V̇o2max was taken as the highest average oxygen consumption recorded over 30 s (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| n | 7 |

| Age, yr | 24 (4) |

| Height, cm | 178.2 (8.4) |

| Weight, kg | 82.2 (12.9) |

| BSA, m2 | 1.98 (0.19) |

| V̇o2max, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 57.0 (7.7) |

| HRmax, beats·min−1 | 195 (3) |

| Body fatSiri, % | 15.7 (5.6) |

Data are expressed as means (SD). BSA, body surface area; HRmax, maximal heart rate during treadmill protocol; V̇o2max, maximal oxygen consumption.

Cold Acclimation

Volunteers participated in a 7-day cold acclimation protocol consisting of daily cold water immersions lasting no more than 1 h a day. On these days, participants arrived between 0700 and 1000 to begin the water immersions. They changed into swim trunks and were fitted with a heart rate monitor (V800 watch with H7 wearlink, Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland), neoprene gloves, and boots. After baseline measures, participants were submerged up to their clavicles in a 14°C circulated cold water bath. Bath temperature was maintained by adding ice every 10–15 min. On days 1 and 7, esophageal temperature (Tes) was measured using a pediatric thermocouple probe of ~2-mm diameter (Mon-a-therm general purpose, Mallinckrodt Medical, St. Louis, MO) inserted ~40 cm past the entrance of the nostril and confirmed every 5 min with aural canal temperature measurement (Taural; Welch Allyn Braun ThermoScan Pro 6000; Braun, Kronberg, Germany). On days 2–6 of the cold water immersion acclimation, only Taural was used to monitor changes in core temperature, to reduce the discomfort for participants. Once the 1-h immersion was completed or the core temperature reached 35.0°C (Tes for days 1 and 7, Taural, for days 2–6), participants exited the bath, were dried, and passively warmed before changing into warm clothing.

Preacclimation and Postacclimation Acute Cold Exposure

Acute cold experimental sessions were conducted the day before and the morning immediately following the 7-day cold acclimation (day 8) using a LCS combined with a mean skin temperature () clamping system set at 26°C for the duration of the cold exposure, as described previously (8). These sessions were started between 0700 and 0930, following a 24-h period, with no strenuous physical activity, caffeine, or alcohol consumption. The evening before the test, participants were provided with a standardized meal (2489 kJ or 595 kcal; 55% CHO, 21% fat, 24% protein), and subjects were asked to arrive at the laboratory following a 12–14-h fast. Upon arrival, subjects changed into undergarments and were then instrumented with T-type (copper/constantan) thermocouples integrated into heat flow sensors (Concept Engineering, Old Saybrook, CT) and surface electromyography electrodes (Myomonitor, Delsys, Natick, MA). Participants were then instructed to complete a series of muscle contractions to measure maximal voluntary contractions (MVC) of the muscles being measured for shivering activity. Participants were then fitted with the LCS and asked to void their bladders. Subjects then lay reclined for 60 min in ambient conditions (23–25°C), following which, baseline measures were taken. Thereafter, the LCS was perfused with cold water, initially at −10°C to accelerate reaching the target of 26°C. Water temperature was regulated as described previously using feedback from skin temperature sensors and a custom-designed program along with a temperature and flow-controlled circulation bath, to maintain subject skin temperature at 26°C throughout the 150-min exposure (8) (Fig. 2B). Thermal responses, including tympanic temperature, shivering activity, and metabolic rate were continually measured during baseline and throughout the 150 min of cold exposure.

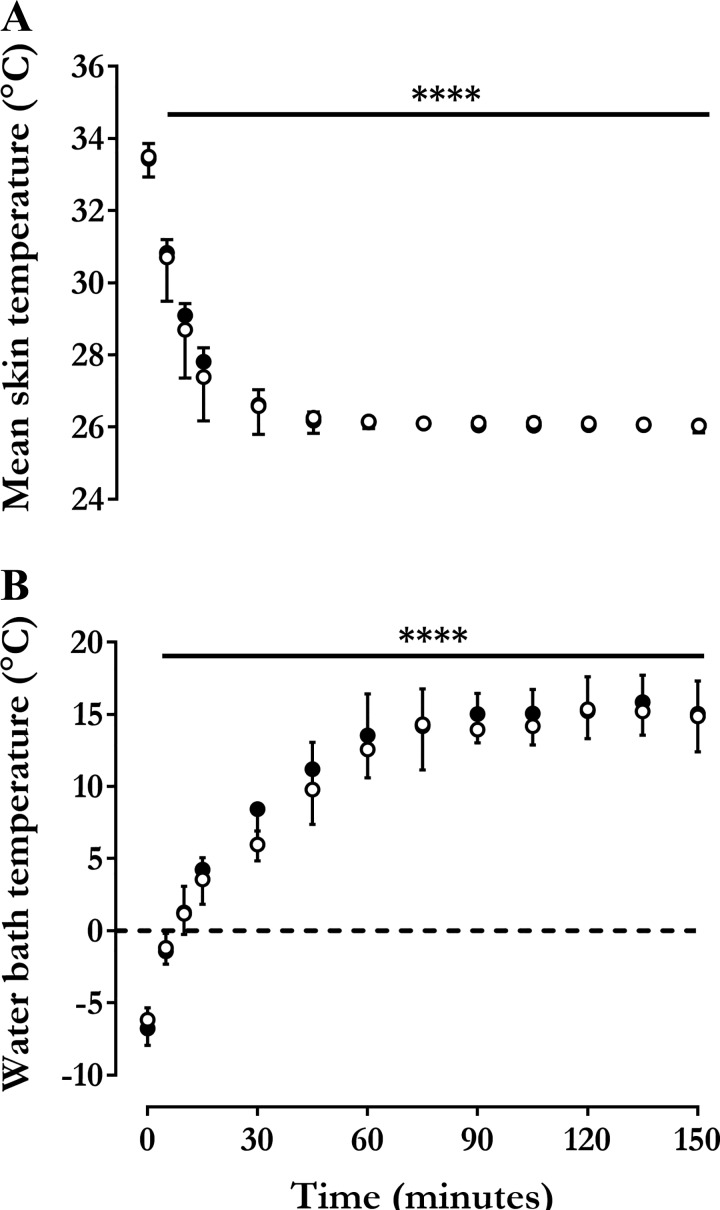

Fig. 2.

Mean skin and water bath temperatures. Changes in mean skin temperature (, °C) (A) and circulating water bath temperature (Twater, °C) (B) measured during an acute cold exposure before (○) and after (●) cold acclimation. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 7 men). Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ****P < 0.0001 vs. Time = 0 min.

Thermal responses.

Core temperature during the mild acute cold exposures was measured from Taural. Mean during the 150-min acute cold exposure was monitored continuously using heat flux sensors fixed to the skin [using area-weighted equation from 12 sites (weighting) (18): forehead (7%), chest (9.5%), biceps (9%), forearm (7%), abdomen (9.5%), lower back (9.5%), upper back (9.5), front calf (8.5%), back calf (7.5%), quadriceps (9.5%), hamstrings (9.5%), and hand (4%)], and maintained around 26.0°C.

Metabolic measures and heat production.

Whole body metabolic rate and fuel selection were quantified continuously by indirect calorimetry using a Field Metabolic System, a flow-through open circuit respirometry system (Sable Systems, Las Vegas, NV) measuring oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and carbon dioxide production (V̇co2). Carbohydrate and lipid utilization rates were calculated using the following Eqs. 1 and 2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where V̇co2 (l/min) and V̇o2 (l/min) were corrected for the volumes of O2 and CO2 corresponding to protein oxidation (1.010 and 0.843 l/g, respectively). Protein oxidation was estimated at 66 mg/min (14–16). Energy potentials of 16.3, 40.8, and 19.7 kJ/g were used to calculate the amount of heat produced from glucose, lipid, and protein oxidation, respectively (20, 24).

Thermal sensation.

Subjective thermal sensation was determined every 30 min by asking the subjects to identify their perception of the exposure temperature on the basis of a 9-point Likert scale, with −4 and +4 being the coldest and warmest ever experienced, respectively, and 0 feeling neither cold nor warm. This is a modification of the scale described previously (23).

Shivering intensity.

Shivering activity was measured using a wireless EMG system (Myomonitor IV, Delsys, Natick, MA). Surface EMG electrodes were placed on four muscles: musculus trapezius superior, musculus pectoralis major, musculus rectus femoris, and musculus vastus lateralis. Each skin site was prepared and cleaned using 3M Red Dot Trace Prep (3M Canada, London, ON, Canada) and ethanol swabs (Alcohol Prep Pad, Dukal Corporation). The EMG electrodes were placed on the right side of the body, directly over each muscle belly. This was marked with an indelible skin marker to allow consistent placement between experimental sessions. Raw EMG signals were collected at 1,000 Hz, filtered to remove spectral components below 20 Hz and above 500 Hz, as well as 60-Hz contamination from related harmonics, using custom-designed MATLAB algorithms (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Shivering activity of the four individual muscles was measured for 10 min during baseline and continuously throughout the acute cold exposure. Participants were encouraged and reminded to minimize voluntary muscle activity during recording periods.

Shivering intensity of individual muscles was determined from root-mean-square (RMS) values calculated from raw EMG signals using a 50-ms overlapping window (50%). Baseline RMS values (5-min average measured before cold exposure) are subtracted from the shivering RMS values and the RMS values obtained from maximum voluntary contractions (MVCs) (RMSmvc). Shivering intensity was normalized to RMSmvc.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 7), unless indicated otherwise. Paired Student’s t-test was used to compare between acute cold exposure experimental sessions. A repeated-measures ANOVA with acclimation status, temperature, and their interaction as independent variables was used to analyze acclimation- and temperature-dependent differences in thermal responses (Tes,, and water bath temperature), metabolic responses (, CHOox, and FATox), EMG activity (shivering intensity) over time (Time = 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 min used for analysis). Bonferroni’s multiple-comparisons post hoc test was used, where applicable. Statistical differences were considered significant when the P value was <0.05. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine correlations between variables. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 21; SPSS, Chicago, IL) or GraphPad Prism (version 7; GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Cold Acclimation

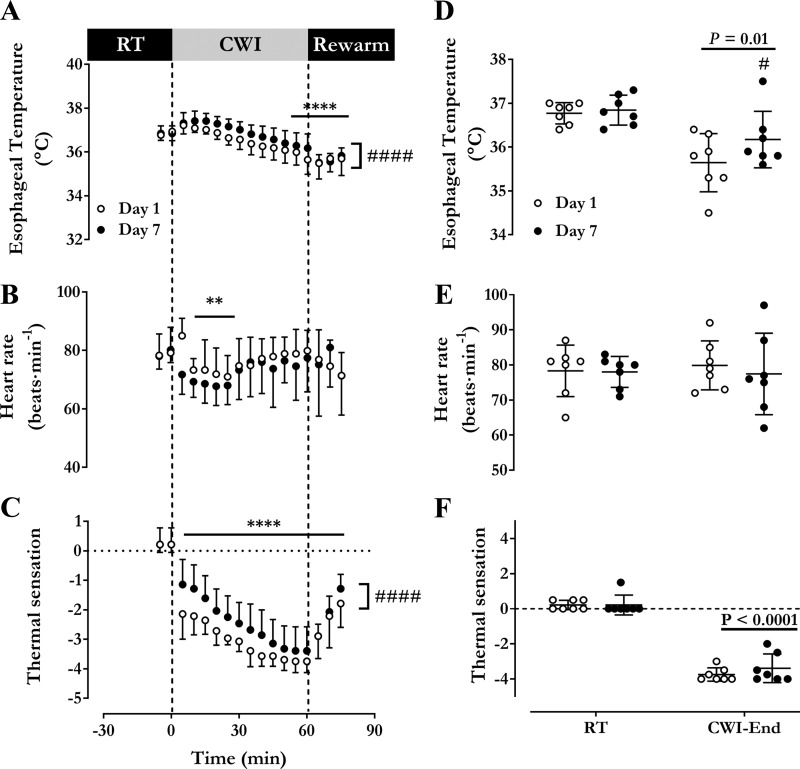

Changes in Tes, HR, and thermal sensation over the 60 min of cold water immersion for day 1 and day 7 are presented in Fig. 1. Water temperature was not different between day 1 and day 7, averaging 14.5°C (SD 0.1) and 14.4°C (SD 0.1), respectively (P = 0.36). Esophageal temperature decreased more significantly during the water immersion on day 1 [36.8°C (SD 0.2) to 35.6°C (SD 0.7)] than on day 7 [36.8°C (SD 0.3) to 36.2°C (SD 0.6)] (P = 0.03) (Fig. 1, A and B). Average HR throughout cold water immersion was higher on day 1 [76 beats/min (SD 6)] compared with day 7 [73 beats·min−1 (SD 7)] (P = 0.004) (Fig. 1C). Thermal sensation was found to decrease continuously during cold water immersion but was significantly lower throughout day 1 compared with day 7 [day 1 at −3.1 (SD 0.3) to day 7 at −2.5 (SD 0.7), P = 0.02] (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Cold water immersion acclimation. Time course of esophageal temperature (A), heart rate (B), and thermal sensation at room temperature (RT) (C), during an acute 14°C cold water immersion (CWI) and during a rewarming period on day 1 and day 7 of the cold acclimation protocol. Average esophageal temperature (D), heart rate (E), and thermal sensation (F) of final 5 min at room temperature and cold water immersion. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 7 men). Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 vs. Time = 0 min. #P < 0.01, ####P < 0.0001 vs. day 1.

Preacclimation and Postacclimation Acute Cold Exposure

Thermal responses.

A computer-controlled system set at a of 26°C (SD 0.1) was used to standardize the stimulus for pre- and post-cold acclimation. The resulting changes in and water bath temperature over the 150 min of acute cold exposure are presented in Fig. 2. By design, fell significantly during cold exposure, stabilizing at 26.1°C (SD 0.04) before and 26.0°C (SD 0.08) after the cold acclimation (P = 0.91) (Fig. 2A). Water temperature circulating through the suit increased progressively, from −6.2°C (SD 0.8) °C at the start of cooling and stabilizing at 14.9°C (SD 2.5) by the end of cold exposure preacclimation and from −6.8°C (SD 1.2) to 15.0°C (SD 2.6) postacclimation (Fig. 2B). There was no difference in starting (P = 0.32) or steady-state water temperature (P = 0.89).

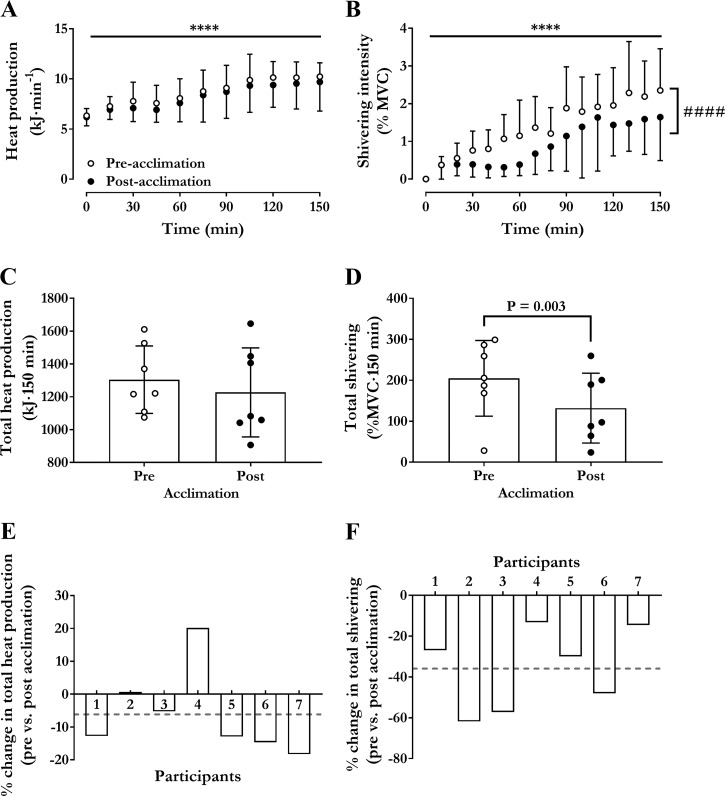

Heat production and fuel selection.

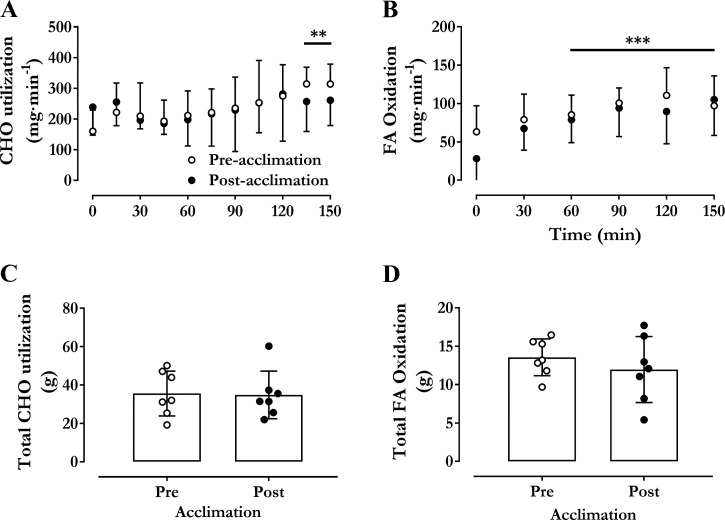

Changes in pre- to post-cold acclimation are shown in Fig. 3. Time course and total heat production (as area under the curve, AUC) were the same before and after cold acclimation (Fig. 3, A and C, effect of time P < 0.0001). The increased on average 1.54-fold from 6.3 kJ/min (SD 0.3) [304 ml O2/min (SD 35)] at baseline to 10.2 kJ/min (SD 1.4) [482 ml O2/min (SD 67)] in the last 30 min in the cold before acclimation and from 6.2 kJ/min (SD 0.3) [292 ml O2/min (SD 39)] at baseline to 9.6 kJ/min (SD 2.6) [458 ml O2/min (SD 125)] in the last 30 min in the cold after acclimation (Fig. 3A, P < 0.0001). The AUC for , or the total amount of heat produced, averaged 1304 kJ·150 min (SD 205) before cold acclimation and 1227 kJ·150 min (SD 272) after cold acclimation (Fig. 3C, P = 0.28). Similarly, as shown in Fig. 4, there was no significant difference in CHO and lipid use (rate or AUC) during the 150 min in the cold. Total CHO utilization over the 150 min averaged 35.6 g (SD 11.7) [580 kJ (SD 191) and 51% (SD 11)] before cold acclimation and 34.8 g (SD 12.4) [568 kJ (202) and 44% (SD 8)] after cold acclimation (P = 0.88). Total lipid utilization over 150 min averaged 13.6 g (SD 2.4) [553 kJ (SD 98) and 38% (SD 12)] before cold acclimation and 12.0 g (SD 4.3) [488 kJ (SD 176) and 43% (SD 9)] after cold acclimation (P = 0.37).

Fig. 3.

Thermogenic responses to acute cold exposure. Changes in rate of metabolic heat production (kJ/min) (A), shivering intensity [% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC)] (B), total heat production (kJ·150 min) (C), and total shivering (%MVC·150 min) (D) during an acute cold exposure at a mean skin temperature of 26°C before and after cold acclimation. Percent change in heat production (B) and shivering intensity (F) from before to after cold acclimation for each participant. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 7 men). Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ****P < 0.0001 vs. Time = 0 min. ####P < 0.0001 vs. preacclimation. Student’s t-test used in D.

Fig. 4.

Substrate utilization. Changes in rate of carbohydrate (CHO) (A), lipid oxidation (B), total carbohydrate (C), and lipid oxidation (D) during an acute cold exposure at a mean skin temperature of 26°C before and after cold acclimation. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 7 men). Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 vs. Time = 0 min.

Shivering response.

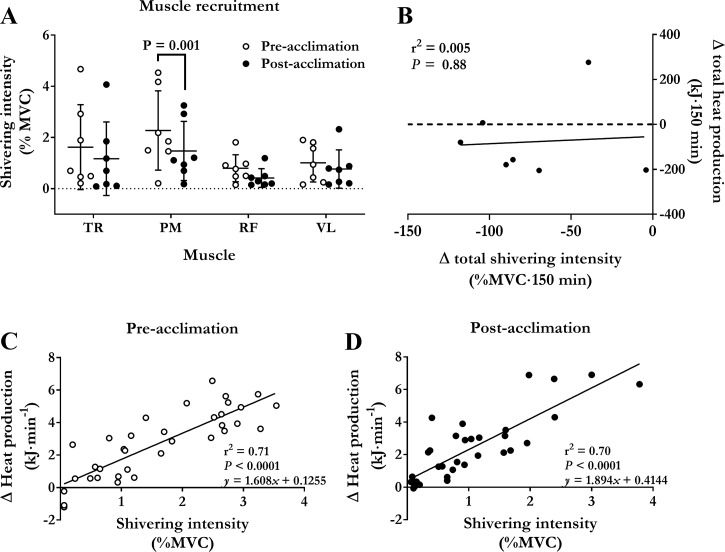

Changes in shivering intensity during the mild cold are shown in Fig. 3. Shivering intensity increased throughout the mild cold exposure in both preacclimation and postacclimation conditions (Fig. 3B; P ≤ 0.0001). Total shivering intensity (AUC) decreased by 36% (SD 20) from 205% MVC·150 min (SD 92) preacclimation to 132% MVC·150 min (SD 85) postacclimation (P = 0.003). This postacclimation decrease in shivering activity occurred primarily in the musculus pectoralis [2.3% MVC (SD 1.5) to 1.5% MVC (SD 1.2), P = 0.001] (Fig. 5A). There was no association between the acclimation-induced change in total heat production and shivering intensity (r = 0.07; P = 0.88) (Fig. 5B). There was a strong association observed between cold-induced thermogenesis and shivering intensity both preacclimation and postacclimation (r = 0.84 preacclimation versus r = 0.84 postacclimation, P < 0.0001 (Figs. 5, B and C). The slopes of the regression lines were not different preacclimation compared with postacclimation (1.6 kJ·min−1·%MVC−1 preacclimation versus 1.9 kJ·min−1·%MVC−1 postacclimation; P = 0.31).

Fig. 5.

Muscle recruitment pattern contribution of ST to heat production. A: differences in shivering intensity for trapezius (TR), pectoralis (PM), rectus femoris (RF), and vastus lateralis (VL) during an acute cold exposure at a mean skin temperature of 26°C before and after cold acclimation. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 7 men). Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. B: relationship between acclimation-induced change in total heat production and total shivering intensity (difference between preacclimation and postacclimation total heat production and shivering intensity) in men exposed to an acute cold. Relationship between cold-induced changes in heat production and shivering intensity in men exposed to a cold eliciting a mean skin temperature of 26°C for 150 min before (C) and following a 7-day (D) 14°C cold-water immersion acclimation protocol. Values presented are from five sampling intervals during cold exposure (time = 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 min) from all subjects.

DISCUSSION

Previous investigations have shown that daily mild cold exposure can increase the thermogenic contribution of NST and decrease ST within 10–20 days (3, 10). In one instance, ST was reduced by 50% within 10 days of daily cold air exposure (10). Others, however, have posited that the greatest metabolic effects resulting from a cold-acclimation protocol would likely require a daily stimulus sufficiently cold or long enough in duration to elicit a decrease in core temperature (32). We show that during an individualized acute cold exposure designed to elicit a ~1.5-fold increase in metabolic rate both before and after the cold acclimation, ST is 36% lower following a 7-day cold water immersion acclimation protocol (Fig. 5). This observation confirms that NST can be increased substantially by as little as 7 days of cold exposure and can compensate for any decreases in ST to maintain thermogenesis. Together, these observations exemplify the important metabolic flexibility of humans to sustain under compensable cold conditions using various thermogenic mechanisms (3) and confirm that changes in the contribution of NST can occur even with only a week of daily cold water immersion.

Seven-Day Cold Water Immersion Acclimation Protocol

When compared with heat acclimation, far less is known on the capacity of humans to modify thermoregulatory processes in response to repeated cold exposure. Following up on our previous cold acclimation work (3, 5, 8), we opted to use in this study an uncompensable cold acclimation protocol consisting of 7 days of 14°C water immersion in an attempt to induce faster and larger increases in the contribution of NST to total than previously obtained from a milder cold acclimation. As such, the present 7-day cold acclimation protocol was designed to induce daily decreases in core temperature of ~1°C [1.2 (SD 0.8) on day 1 and 0.7°C (SD 0.7) on day 7], resulting in intense shivering during the water immersion and the subsequent passive rewarming after the immersion (17, 25). Although the cooling stimulus was colder than our previous compensable cold acclimations, which used 10°C water through the LCS (3, 5) or maintained at 28°C (8), all participants in the present study were able to tolerate the complete immersion duration of 60 min, and core temperature never reached the critical limit for water extraction of 35°C.

Given the water temperature used in this acclimation protocol, the heart rate upon initial water immersion (first 5 min) rose rapidly preacclimation to 85 beats/min (SD 6) [from 78 beats/min (SD 7) at room temperature], a marker of the sympathetic stimulation resulting from “cold shock” (28), but fell immediately to 72 beats/min (SD 7) postacclimation [from 78 beats/min (SD 7) at room temperature] (Fig. 1C). Our results also indicated that Tes cooling rate was attenuated, on average by ~0.01°C/min, from day 1 to day 7 (Figs. 1, A and B), while thermal sensation was significantly warmer following cold acclimation (average rating of −3.1 vs. −2.5) (Figs. 1, E and F. These results suggest that the heat-loss defense mechanisms (vasoconstriction) and/or the thermogenic responses were increased postacclimation, resulting in slower cooling and improved thermal sensation. Unfortunately, in the present study, we did not quantify changes in either or throughout the 7-day cold-water immersion protocol. Consequently, the exact processes responsible for the reduced rate of body core cooling remain unknown. However, these results appear to suggest a potential blunted sympathetic response upon entering the cold water and that NST, likely from skeletal muscles, was significantly upregulated to support a greater thermogenic rate. This increased thermogenic response would be consistent with a “metabolic” acclimation phenotype that would be anticipated from an uncompensable cold acclimation protocol (32).

Contribution of ST and NST Following Intense 7-Day Cold Acclimation

Quantifying the relative contribution of ST and NST to total during cold exposure in humans presents a number of important challenges (see topical review in Ref. 4). The greatest challenge relates to the fact that whole body NST cannot be quantified directly because it involves all cold-induced stimulation of thermogenic processes in various cells of the body that are not linked to muscle contractions. For this reason, we can typically only qualitatively assess modifications in NST based on changes in whole body ST activity at the same given (3, 5, 12). To achieve this objective, we elected to use a liquid-cooled suit coupled with a computer-controlled chiller to clamp and associated changes in during an acute cold exposure before and after cold acclimation. Using this method, we clamped average at 26°C to achieve the same time course and overall ~1.6-fold increase in before and after cold acclimation (Fig. 3A). Under these standardized conditions, we showed that whole body ST was reduced by ~40% after the cold acclimation protocol when compared with responses measured before the cold acclimation (Fig. 3D). This change can be explained by a combined slower progressive rise in ST and a more than ~30% reduction in average ST intensity measured in the last 30 min of cold exposure (Fig. 3). This large reduction of ST at the same clearly indicates that cold acclimation resulted in a major stimulation in NST processes. This has significant implications for cold endurance, tolerance and ultimately, survival. Whether such significant changes in the recruitment of NST processes can be accomplished with a shorter similar acclimation protocol or slightly longer but milder cold-water immersion is also of importance. This 7-day cold acclimation protocol was selected to account for what we believed would be the minimum amount required to observe physiologically relevant differences in and ST, based on the only other cold acclimation protocol to examine these outcomes simultaneously using moderate cold exposure (10). It is important to note that changes in shivering intensity observed in the present study may be specific to conditions where increases in heat loss induced by cold exposure may be matched by increases in , termed compensable cold exposure. It is unclear whether these changes in thermogenic responses would also be observed during uncompensable cold exposure such as cold-water immersion.

Of great interest is also the effects of a cold acclimation and associated reduction in ST on the reliance on CHO to fuel heat production (13). Previous work has shown that muscle glycogen accounts for ~80–85% of all the glucose required to sustain total CHO oxidation, at cold exposures eliciting a metabolic heat production that is 2.0 to 3.5 times above basal levels (13). Therefore, we were interested in determining whether the ~40% decrease in shivering intensity following cold acclimation found here could preserve the limited CHO reserves, which despite its significant reliance in the cold only represent ~1% of total energy reserves (7). Fuel selection can be modified by recruiting different muscle groups, different subpopulations of muscle fibers within the same muscle, and different metabolic pathways within the same muscle fibers. Here, we show that shivering intensity was reduced in all muscles examined following cold acclimation, but decreased most significantly in the pectoralis, falling by 35% (Fig. 5). Interestingly, this overall reduction in ST and increase in NST did not modify absolute rates and relative contribution of CHO and lipid to total during cold exposure (Fig. 4). This finding implies that the NST processes that were involved in modulating ST must necessarily use a similar fuel mixture to sustain .

Contribution of Various Tissues and Mechanisms to NST

Our study confirms that NST can increase substantially to reduce ST following a 7-day cold acclimation in 14°C water. As in other mammals, such a reduction in ST during cold exposure confers a survival advantage by reducing the discomfort of involuntary muscle contractions and its effects on locomotion and motor control (9, 21). However, identification of the exact tissues and mechanisms involved in increasing NST during acute cold exposure or following cold acclimation is particularly difficult at the tissue and/or whole body level. Previously, we have shown that one source of NST that can increase through repeated mild-cold exposure in humans is BAT thermogenesis (3, 5, 8). Despite increasing BAT volume by 45% and its thermogenic capacity by 150–182% in these previous studies, this had no effect on fuel selection. Therefore, it is possible that the thermogenic contribution of BAT increased in the present study but did not impact fuel selection when exposed to a mild acute cold. Given its small relative size (<1% of body weight in humans) (6, 30) and thermogenic contribution (<1% of whole body heat production) (29), it is more probable that another source of NST is responsible for the improved thermal sensation and reduced body core cooling in the cold water immersion and the increased NST in the acute mild cold.

Skeletal muscles constitute another important target for cold-induced NST, as it accounts for 42% of total body weight (19). We and others have shown that acute cold exposure increases proton leak in the vastus lateralis (3, 31), another source of NST, but 4 wk of mild daily cold exposure abolishes this response (3). In addition, in contracting muscles cytosolic Ca2+ levels rapidly increase, and sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) must pump Ca2+ back into the SR to maintain its store, accounting for ~24–58% of tissue metabolic rate in contracting muscles in rodents (26). This Ca2+ release is critical for muscle contractions during shivering, but in cold-acclimated rodents, calcium leaks into the cytosol via ryanodine receptors, leading to excessive activation of SERCA to pump Ca2+ back into the SR, generating heat in the process (2). With humans possessing significantly greater levels of the SERCA regulatory proteins (1) compared with rodents and relying to a greater extent on skeletal muscle to produce heat, this thermogenic mechanism could likely be quite significant in humans and serve as a form of NST following cold acclimation. Further investigations are required to determine the contribution of these skeletal muscle-derived thermogenic processes in such a cold acclimation.

In summary, we have demonstrated that seven consecutive days of cold-water immersion can decrease shivering intensity by 36%, nearly double what we previously described in response to a 4-wk compensable cold acclimation. The decreased shivering intensity for the same whole body heat production in response to a mild acute cold exposure, suggests a significant increase in the contribution of NST following 7 days of cold water immersion. This had no effect on whole body fuel selection, which suggests that the source of NST must rely on a similar fuel mixture to produce this heat. Although several studies have examined the effects of repeated cold exposure on whole body heat production in humans, few have ever simultaneously quantified the contribution of shivering and by extension the contribution of NST to this heat production. This not only fills a critical gap to improve our understanding of the physiological and metabolic responses to chronic cold, but it also provides critical information to develop strategies to improve human survival and tolerance in cold climates. With the growing naval traffic expected in arctic regions as a result of the exploration of natural resources, research, military operations, tourism, and expansion of shipping lanes for cargo ships, there is an increase in occupational exposure to cold and increased risk for ship groundings. The grounding of naval vessels poses several risks, as survivors may be required to wait 5–7 days before being rescued. In addition, there remain critical knowledge gaps in our understanding of the cold acclimation responses in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly or individuals with impaired motor function, as well as in individuals originating from warm climates, which clearly need to be addressed in future studies. Consequently, further work is necessary to understand the thermogenic processes that may be modulated under such a short, but intense, cold acclimation and determine the minimal acclimation duration and cooling temperature required to elicit metabolic changes that may be critical for survival and performance in cold environments.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC Canada) to FH (RGPIN/2016-05291).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.G., D.P.B., G.P.K., and F.H. conceived and designed research; K.G., B.J.F., and H.C.T. performed experiments; K.G., D.P.B., B.J.F., and H.C.T. analyzed data; K.G., D.P.B., B.J.F., H.C.T., G.P.K., and F.H. interpreted results of experiments; K.G. and D.P.B. prepared figures; K.G. and D.P.B. drafted manuscript; K.G., D.P.B., B.J.F., H.C.T., G.P.K., and F.H. edited and revised manuscript; K.G., D.P.B., B.J.F., H.C.T., G.P.K., and F.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for their commitment and collaboration.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babu GJ, Bhupathy P, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Periasamy M. Differential expression of sarcolipin protein during muscle development and cardiac pathophysiology. J Mol Cell Cardiol 43: 215–222, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal NC, Maurya SK, Sopariwala DH, Sahoo SK, Gupta SC, Shaikh SA, Pant M, Rowland LA, Bombardier E, Goonasekera SA, Tupling AR, Molkentin JD, Periasamy M. Sarcolipin is a newly identified regulator of muscle-based thermogenesis in mammals. Nat Med 18: 1575–1579, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nm.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondin DP, Daoud A, Taylor T, Tingelstad HC, Bézaire V, Richard D, Carpentier AC, Taylor AW, Harper ME, Aguer C, Haman F. Four-week cold acclimation in adult humans shifts uncoupling thermogenesis from skeletal muscles to brown adipose tissue. J Physiol 595: 2099–2113, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blondin DP, Haman F. Shivering and nonshivering thermogenesis in skeletal muscles. Handb Clin Neurol 156: 153–173, 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63912-7.00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Tingelstad HC, Noll C, Kunach M, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte ÉE, Carpentier AC, Richard D, Haman F. Increased brown adipose tissue oxidative capacity in cold-acclimated humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99: E438–E446, 2014. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blondin DP, Labbé SM, Turcotte EE, Haman F, Richard D, Carpentier AC. A critical appraisal of brown adipose tissue metabolism in humans. Clin Lipidol 10: 259–280, 2015. doi: 10.2217/clp.15.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blondin DP, Tingelstad HC, Mantha OL, Gosselin C, Haman F. Maintaining thermogenesis in cold exposed humans: relying on multiple metabolic pathways. Compr Physiol 4: 1383–1402, 2014. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blondin DP, Tingelstad HC, Noll C, Frisch F, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Turcotte EE, Richard D, Haman F, Carpentier AC. Dietary fatty acid metabolism of brown adipose tissue in cold-acclimated men. Nat Commun 8: 14146, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellani JW, Tipton MJ. Cold stress effects on exposure tolerance and exercise performance. Compr Physiol 6: 443–469, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis TRA. Chamber cold acclimatization in man. J Appl Physiol 16: 1011–1015, 1961. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois D, Dubois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 17: 863–871, 1916. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1916.00080130010002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosselin C, Haman F. Effects of green tea extracts on non-shivering thermogenesis during mild cold exposure in young men. Br J Nutr 110: 282–288, 2013. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512005089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haman F, Blondin DP. Shivering thermogenesis in humans: Origin, contribution and metabolic requirement. Temperature (Austin) 4: 217–226, 2017. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2017.1328999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haman F, Péronnet F, Kenny GP, Doucet E, Massicotte D, Lavoie C, Weber J-M. Effects of carbohydrate availability on sustained shivering I. Oxidation of plasma glucose, muscle glycogen, and proteins. J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 32–40, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00427.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haman F, Péronnet F, Kenny GP, Massicotte D, Lavoie C, Scott C, Weber J-M. Effect of cold exposure on fuel utilization in humans: plasma glucose, muscle glycogen, and lipids. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 77–84, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00773.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haman F, Péronnet F, Kenny GP, Massicotte D, Lavoie C, Weber J-M. Partitioning oxidative fuels during cold exposure in humans: muscle glycogen becomes dominant as shivering intensifies. J Physiol 566: 247–256, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haman F, Scott CG, Kenny GP. Fueling shivering thermogenesis during passive hypothermic recovery. J Appl Physiol (1985) 103: 1346–1351, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00931.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy JD, Du Bois EF, Soderstrom GF. The technic of measuring radiation and convection. J Nutr 15: 461–475, 1938. doi: 10.1093/jn/15.5.461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Wang Z, Heymsfield SB, Baumgartner RN, Gallagher D. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: estimation by a new dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry method. Am J Clin Nutr 76: 378–383, 2002. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.2.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livesey G, Elia M. Estimation of energy expenditure, net carbohydrate utilization, and net fat oxidation and synthesis by indirect calorimetry: evaluation of errors with special reference to the detailed composition of fuels. Am J Clin Nutr 47: 608–628, 1988. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meigal A. Gross and fine neuromuscular performance at cold shivering. Int J Circumpolar Health 61: 163–172, 2002. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v61i2.17449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouellet V, Labbé SM, Blondin DP, Phoenix S, Guérin B, Haman F, Turcotte EE, Richard D, Carpentier AC. Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. J Clin Invest 122: 545–552, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI60433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passias TC, Meneilly GS, Mekjavić IB. Effect of hypoglycemia on thermoregulatory responses. J Appl Physiol (1985) 80: 1021–1032, 1996. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.3.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Péronnet F, Massicotte D. Table of nonprotein respiratory quotient: an update. Can J Sport Sci 16: 23–29, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proulx CI, Ducharme MB, Kenny GP. Effect of water temperature on cooling efficiency during hyperthermia in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 94: 1317–1323, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00541.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolfe DFS, Brown GC. Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiol Rev 77: 731–758, 1997. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siri WE. Gross composition of the body. In: Advances in Biolobical and Medical Physics, edited by Lawrence JH and Tobia CA. New York: Academic, 1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tipton MJ, Collier N, Massey H, Corbett J, Harper M. Cold water immersion: kill or cure? Exp Physiol 102: 1335–1355, 2017. doi: 10.1113/EP086283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U Din M. Raiko J, Saari T, Kudomi N, Tolvanen T, Oikonen V, Teuho J, Sipila HT, Savisto N, Parkkola R, Nuutila P, Virtanen KA. Human brown adipose tissue [(15)O]O2 PET imaging in the presence and absence of cold stimulus. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 43: 1878–1886, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3364-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Lans AA, Wierts R, Vosselman MJ, Schrauwen P, Brans B, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in human adults: methodological issues. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 307: R103–R113, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00021.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wijers SL, Schrauwen P, Saris WH, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Human skeletal muscle mitochondrial uncoupling is associated with cold induced adaptive thermogenesis. PLoS One 3: e1777, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young AJ. Homeostatic responses to prolonged cold exposure: human cold acclimatization. Compr Physiol 14: 419–438, 2011. doi: 10.1002/cphy.cp040119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]