Abstract

There is increasing research and interest surrounding biologics and sports medicine. Amnion has the potential to decrease adhesions and possibly protect anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) grafts along with increasing vascularization by acting as a scaffold. Bone marrow concentrate containing mesenchymal stem cells combined with Allosync Pure (Arthrex, Naples, FL) injected into ACL tunnels has the potential to increase the speed and quality of graft bone incorporation, especially when used in the setting of a soft-tissue allograft. Using suture tape augmentation (InternalBrace; Arthrex) with the reconstruction has been thought to increase the early strength of the reconstruction. In this article, we combine all 3 techniques into an all-inside ACL reconstruction that has great potential for an earlier return to play and advanced rehabilitation.

Among young athletes, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is one of the most common ligamentous knee injuries, particularly in those sports requiring cutting and jumping movements.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 It is estimated that over 100,000 athletes will require reconstructive surgery to avoid chronic instability and chondral injury.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Graft rerupture is a major complication affecting many of these athletes, with estimated rates of 6% to 11%.6 Despite changes in surgical technique and graft choice, these rates have not changed significantly over time.7 The current hope is that, by developing techniques that hasten biological incorporation, we can improve these rates and functional outcomes.

A recent study reported that when used with osteochondral allografts, bone marrow concentrate showed superior radiographic outcomes in the knee.8 By combining this concentrate with Allosync Pure (Arthrex, Naples, FL) and grafting both the femoral and tibial tunnels, the goal is to improve graft incorporation. With advances in tissue engineering, biological augmentation of the graft itself may further improve graft incorporation.9, 10 Although amniotic membrane–derived products have yet to be studied in ligament reconstruction of the knee, they have been shown to be effective in the realms of plastic surgery and ophthalmology, providing a theoretical basis for use.11 By combining these 2 techniques with the use of a suture tape (Arthrex), the belief is that we can improve failure rates and functional outcomes of these patients.12 There are early advantages to an all-inside ACL reconstruction such as decreased pain, and when this is combined with biologics, we may be able to accelerate rehabilitation and return to play more than previously anticipated. This article describes the fertilized ACL, a complete biological ACL reconstruction designed to enhance graft bone integration, in addition to faster and improved vascularization of the graft.

Technique

Fig 1, Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4, Fig 5, Fig 6, Fig 7, Fig 8, Fig 9, Fig 10 and Video 1 show the surgical technique.

Fig 1.

Standard graft-link allograft while wrapping amnion circumferentially around graft.

Fig 2.

Graft on preparation station. A No. 4-0 Vicryl suture is used to create a baseball stitch in a running fashion, which is then tied to compress the amnion.

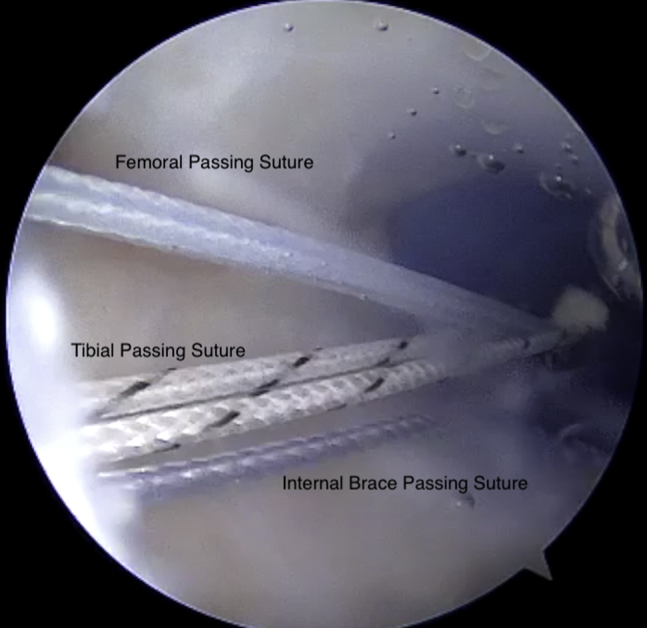

Fig 3.

Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscope, the medial portal is shown with a PassPort cannula inserted and all 3 passing sutures retrieved.

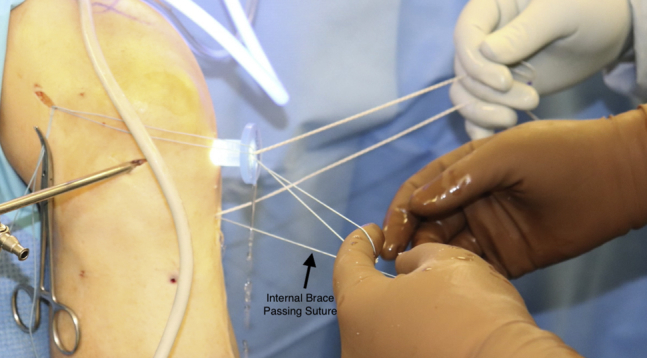

Fig 4.

Viewing outside the knee, the tibial passing sutures, InternalBrace passing sutures, and femoral passing sutures can all be seen docked.

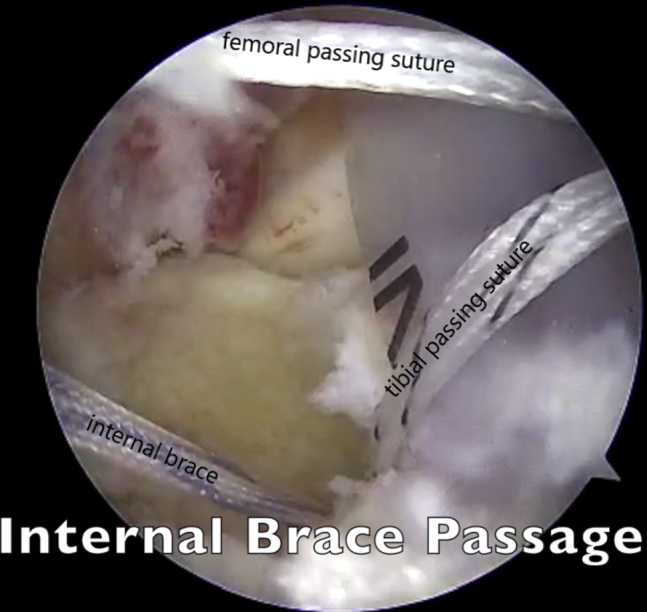

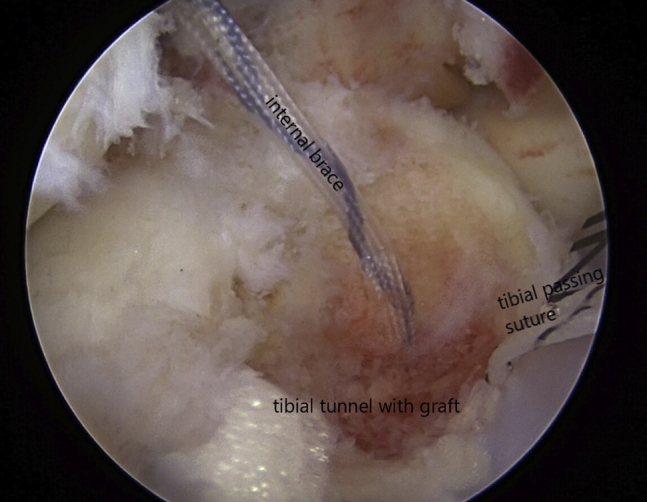

Fig 5.

Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscope, the InternalBrace is being passed from the medial portal and through the tibia.

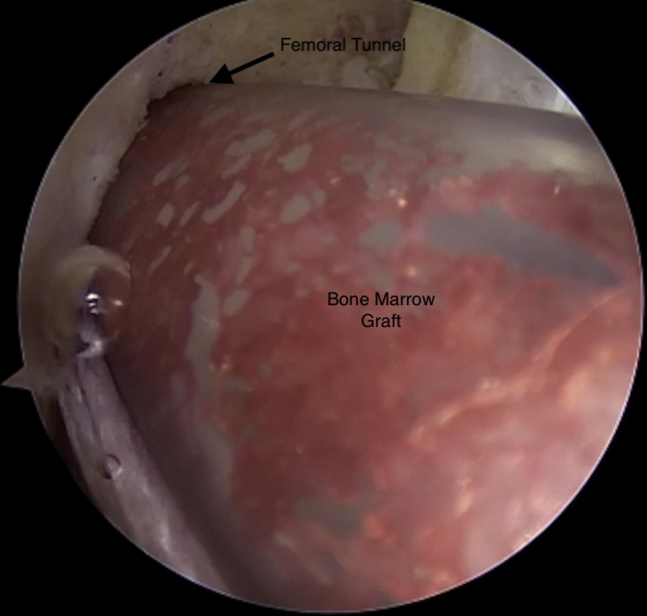

Fig 6.

Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscope, the composite graft is injected into the femoral tunnel using the arthroscopic delivery cannula.

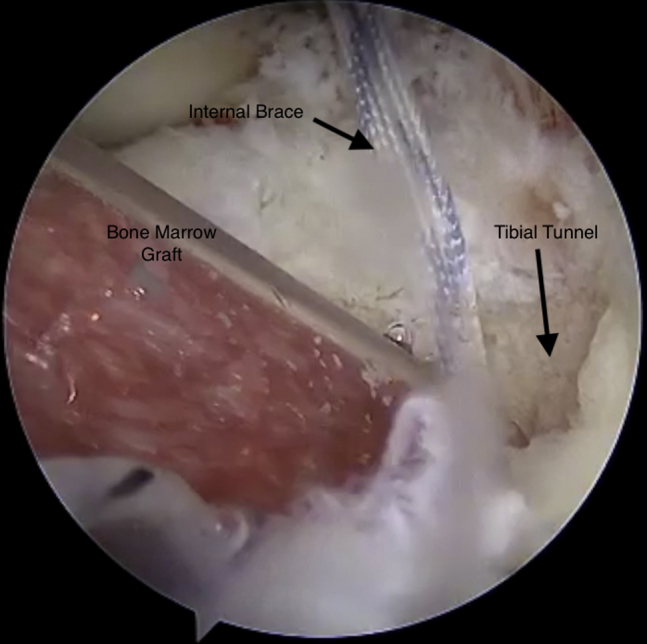

Fig 7.

Viewing from the anteromedial portal with the 30° arthroscope, the composite graft is injected into the tibial tunnel using the arthroscopic delivery cannula.

Fig 8.

Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscope, the composite graft can be seen filling the tibial tunnel.

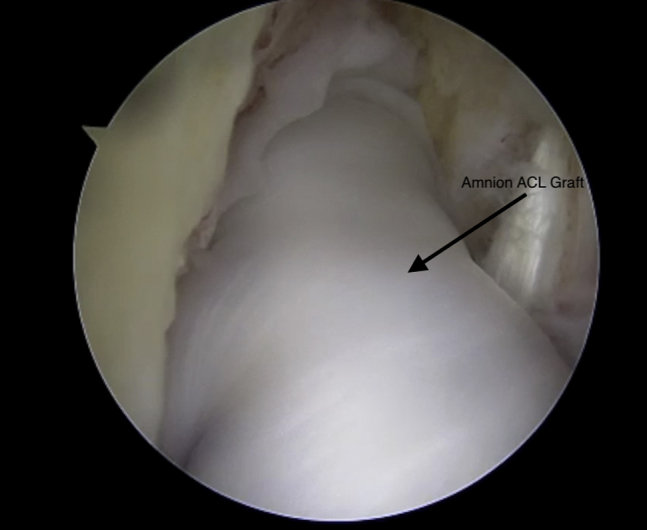

Fig 9.

Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscope, the amnion anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) can be seen within the joint.

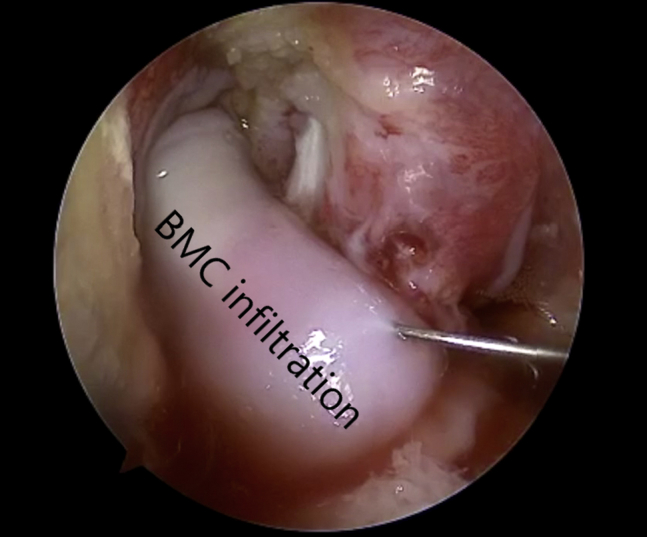

Fig 10.

Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscope, the bone marrow concentrate (BMC) is seen being injected into the amnion anterior cruciate ligament.

Amnion and Graft Preparation

A standard graft-link allograft is prepared, and the femur-sided suspensory fixation loop is lengthened to allow space for injection of the composite graft into the femoral tunnel later in the case. With the epithelial side facing up, the 3 × 6–mm amnion is wrapped around the central portion of the graft (Fig 1). By use of No. 4-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), a standard loop stitch is placed 1 mm from each end of the amnion and tied. These stitches will help seal the amnion. With the use of the same No. 4-0 Vicryl suture, a baseball stitch is then placed in the seam created where the amnion edge is to complete the seal (Fig 2).

Patient Setup

The patient is placed supine in a standard knee arthroscopy position. The operative extremity is placed into a leg holder with a tourniquet applied to the thigh, and the nonoperative extremity is placed in a well-leg pillow.

Bone Marrow Aspiration

Before inflation of the tourniquet, a small stab incision is made just lateral to the tibial tubercle. The aspiration needle and central sharp trocar are inserted while angled proximally at 10°. A mark is made on the needle at 30 mm to avoid overinsertion. The central trocar is removed, and the first few milliliters of aspirate is discarded because of the excess amount of bone. Then, 60 mL of bone marrow is aspirated into heparinized syringes.

Mixing Bone Marrow Aspirate With Allosync Pure

After aspiration of the bone marrow, the aspirate is concentrated using the Arthrex Angel device and a total of 3 mL of the bone marrow is mixed by hand with 5 mL of the Allosync Pure. This mixture is then placed into an arthroscopic cannula delivery device. The remaining 3 mL of bone marrow concentrate is saved for later injection intra-articularly into the amnion after the graft is fixed.

ACL Technique

The tourniquet is inflated, and a standard diagnostic arthroscopy shows the ACL rupture. The allograft graft link sized 74 × 9.5 mm has been prepared on the back table as mentioned earlier with an adjustable button system on the tibial side and suspensory fixation BTB TightRope (Arthrex) on the femoral side. The InternalBrace (Arthrex) is added to the TightRope button opposite the blue passing suture. The ACL remnants in the intercondylar notch are debrided, and a FlipCutter (Arthrex) is used to create a femoral socket through which a FiberStick (Arthrex) is placed and the suture is docked out of the lateral portal. A 12 × 4 mm PassPort cannula (Arthrex) is then placed in the medial portal. A FlipCutter is used to create the tibial socket. A TigerStick (Arthrex) and passing suture for the InternalBrace are passed through the tibia.

Suture Management and Passage

All 3 passing sutures are brought through the PassPort cannula medially (Fig 3). These are docked and clamped to prevent suture bridges (Fig 4). First, the femoral sutures are loaded into the femoral FiberStick, and the TightRope button is deployed on the lateral cortex of the femur. Next, the InternalBrace suture is passed through the tibia using the InternalBrace passing suture (Fig 5).

Composite Graft Injection

By use of the arthroscopic cannula loaded with the bone marrow concentrate composite graft, we inject the graft into the femoral tunnel (Fig 6). This is performed through the medial PassPort cannula. The delivery device is then moved to the lateral portal, and the knee is hyperflexed to inject the composite graft into the tibial tunnel (Fig 7). The tibial graft is seen completely filling the tibial tunnel (Fig 8).

ACL Graft Passage

With the white suture out of the femoral tunnel, 10 mm of femoral graft is pulled into the femur. The TigerStick sutures are then used to pass the tibia-sided sutures through the tibia. After the tibia side of the graft is docked into the tunnel, the remaining femur-sided graft is pulled into the femur until the amnion is centered in the joint. Standard button fixation on the tibia is used at 30° of flexion of the knee (Fig 9). The InternalBrace is then placed into a 4.75 mm SwiveLock (Arthrex) and fixed into the anterior medial tibia at full extension of the knee.

Bone Marrow Concentrate Injection

After fixation of the ACL graft, a 25-gauge needle is used to inject the remaining bone marrow concentrate into the amnion. The amnion should swell and become pink. Some small amounts of leakage from the amnion will occur (Fig 10).

Discussion

Incorporation of the graft at the tendon-to-bone interface is paramount to the success of ACL reconstructive surgery. Tunnel osteolysis has been a consistent problem regardless of graft type and remains a problem despite changing surgical techniques.13, 14 We recently published the Lavender technique of tunnel grafting with bone marrow concentrate and Allosync Pure,15 and the current technique combines that technique with the use of amnion. With this multifactorial approach, we are optimistic that we can improve not only tunnel widening but also overall graft incorporation as well as vascularization and, by extension, clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, no clinical studies exist evaluating tunnel grafting in primary ACL reconstruction; however, using biologics as described here, we hope to show revolutionary clinical and radiographic outcomes.8 Likewise, amniotic membrane–derived grafts have not been previously used for this application. The use as a biological scaffold, however, has been occurring for quite some time in the field of wound care and plastic surgery, in which it was applied for complex soft-tissue regeneration.11 We recognize that the cost of the biologics may inhibit widespread use, but for patients at risk of rerupture and for higher-level athletes, this may become a great option to improve outcomes. There are several disadvantages and limitations to the procedure, which include extra time spent in the operating room and increased technical aspects of the procedure (Table 1). The risks of this procedure include those associated with allograft use, including infection, disease transmission, and host rejection. The possibility of host rejection or reaction against the amnion is a concern. We believe this needs to be prospectively studied further to examine these complications. Despite those disadvantages when combined with an allograft reconstruction and using the all-inside technique, the fertilized ACL may be the correct balance to advance rehabilitation and return to play. Together, these modalities provide an approach to improve graft incorporation in ACL reconstruction with the goal of improving clinical outcomes and decreasing graft rerupture rates.

Table 1.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Amnion Graft Augmentation, Bone Marrow Concentrate Injection, and Suture Tape Augmentation in ACL Reconstruction

| Advantages |

| Amnion may lead to faster synovialization and vascularization of the graft. |

| Bone marrow harvesting can be performed in the same surgical field. |

| Stem cells and bone grafting may lead to faster and more robust incorporation in both tunnels. |

| Suture tape augmentation may lead to improved early outcomes and an earlier return to play. |

| Disadvantages |

| Increased cost |

| Increased graft preparation time and operating time |

| Added incision for bone marrow harvest |

| Theoretically increased risk of fracture at aspiration site of tibia |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: C.L. receives personal fees from Arthrex as a consultant. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

The graft can be seen on the preparation station, and the 3 × 6–mm amnion is used to wrap around the graft. The epithelial side of the graft is placed upward. A No. 4-0 Vicryl is then placed in a loop stitch 1 mm from each end of the amnion to secure it to the graft link. Next, a baseball stitch is placed using a No. 4-0 Vicryl suture to further secure the amnion to the graft. The InternalBrace is placed opposite the blue passing suture in the femur-sided button. Bone marrow is aspirated from the proximal tibia. Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscopy, one can see a standard femoral socket and then the tibial FlipCutter. Still viewing from the anterolateral portal, one can see a PassPort in the medial portal, and after drilling of both tunnels, 2 passing sutures from the tibia and 1 from the femur are seen coming out of the medial portal. Next, a view from outside the joint is presented, showing the docked sutures. Continuing viewing from the anterolateral portal, one can see the TightRope is passed up through the femur and then the InternalBrace is passed down through the tibia. A view from outside the joint showing the same step is also presented. With visualization from the anterolateral portal, the composite graft is injected into the femoral tunnel, and then viewing from the medial portal, one can see the injection into the tibial tunnel. Viewing from the anterolateral portal, one can see the ACL graft passed into the femur and down into the tibia. The same view is presented while the graft is being probed, and finally, a 25-gauge needle is used to inject the amnion graft from medially.

References

- 1.Anderson C.N., Anderson A.F. Management of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee in the skeletally immature athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2016;36:35–52. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spindler K.P., Wright R.W. Clinical practice. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2135–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiapour A.M., Murray M.M. Basic science of anterior cruciate ligament injury and repair. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3:20–31. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.32.2000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willadsen E.M., Zahn A.B., Durall C.J. What is the most effective training approach for preventing noncontact ACL injuries in high school-aged female athletes? J Sport Rehabil. 2018:1–5. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2017-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyman S., Koulouvaris P., Sherman S., Do H., Mandl L., Marx R. Epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Trends, readmissions, and subsequent knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2321–2328. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford S.N., Waterman B.R., Lubowitz J.H. Long-term failure of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2013;39:1566–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiggins A.J., Grandhi R.K., Schneider D.K., Stanfield D., Webster K.E., Myer G.D. Risk of secondary injury in younger athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1861–1876. doi: 10.1177/0363546515621554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oladeji L.O., Stannard J.P., Cook C.R. Effects of autogenous bone marrow aspirate concentrate on radiographic integration of femoral condylar osteochondral allografts. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:2793–2803. doi: 10.1177/0363546517715725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heckmann N., Auran R., Mirzayan R. Application of amniotic tissue in orthopedic surgery. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2016;45:E421–E425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribon J.C., Saltzman B.M., Yanke A.B., Cole B.J. Human amniotic membrane-derived products in sports medicine: Basic science, early results, and potential clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2425–2434. doi: 10.1177/0363546515612750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei J., Priddy L., Lim J., Massee M., Koob T. Identification of extracellular matrix components and biological factors in micronized dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2017;6:43–53. doi: 10.1089/wound.2016.0699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith P.A., Bley J.A. Allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction utilizing internal brace augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5:e1143–e1147. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson T.C., Kantaras A., Atay A., Johnson D.L. Tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:543–549. doi: 10.1177/0363546504263151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen J.E., Miller M.D. Knee anterior cruciate ligament injuries: Common problems and solutions. Clin Sports Med. 2018;37:265–280. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavender C., Johnson B., Kopiec A. Augmentation of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with bone marrow concentrate and a suture tape. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e1289–e1293. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The graft can be seen on the preparation station, and the 3 × 6–mm amnion is used to wrap around the graft. The epithelial side of the graft is placed upward. A No. 4-0 Vicryl is then placed in a loop stitch 1 mm from each end of the amnion to secure it to the graft link. Next, a baseball stitch is placed using a No. 4-0 Vicryl suture to further secure the amnion to the graft. The InternalBrace is placed opposite the blue passing suture in the femur-sided button. Bone marrow is aspirated from the proximal tibia. Viewing from the anterolateral portal with the 30° arthroscopy, one can see a standard femoral socket and then the tibial FlipCutter. Still viewing from the anterolateral portal, one can see a PassPort in the medial portal, and after drilling of both tunnels, 2 passing sutures from the tibia and 1 from the femur are seen coming out of the medial portal. Next, a view from outside the joint is presented, showing the docked sutures. Continuing viewing from the anterolateral portal, one can see the TightRope is passed up through the femur and then the InternalBrace is passed down through the tibia. A view from outside the joint showing the same step is also presented. With visualization from the anterolateral portal, the composite graft is injected into the femoral tunnel, and then viewing from the medial portal, one can see the injection into the tibial tunnel. Viewing from the anterolateral portal, one can see the ACL graft passed into the femur and down into the tibia. The same view is presented while the graft is being probed, and finally, a 25-gauge needle is used to inject the amnion graft from medially.