Abstract

Reporting key details of respondent-driven sampling (RDS) survey implementation and analysis is essential for assessing the quality of RDS surveys. RDS is both a recruitment and analytic method and, as such, it is important to adequately describe both aspects in publications. We extracted data from peer-reviewed literature published through September, 2013 that reported collected biological specimens using RDS. We identified 151 eligible peer-reviewed articles describing 222 surveys conducted in seven regions throughout the world. Most published surveys reported basic implementation information such as survey city, country, year, population sampled, interview method, and final sample size. However, many surveys did not report essential methodological and analytical information for assessing RDS survey quality, including number of recruitment sites, seeds at start and end, maximum number of waves, and whether data were adjusted for network size. Understanding the quality of data collection and analysis in RDS is useful for effectively planning public health service delivery and funding priorities.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Key populations, Respondent driven sampling, RDS, Biological and behavioral surveillance

Introduction

The first respondent-driven sampling (RDS) surveys to assess HIV prevalence in addition to risk behaviors were conducted in 2004 [1–3]. Since then hundreds of surveys have been conducted worldwide to capture data from populations considered at higher risk for HIV exposure, including people who use and/or inject drugs (PWUD, PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers (FSW), and other populations considered “hard-to-reach” due to stigma and the practice of illegal behaviors [4–6]. Over the past decade RDS has been widely used, with the endorsement of organizations such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNAIDS, WHO, Global Fund and others, to establish baseline and trend measurements of HIV and other infections prevalence, risk behaviors, and program impact through biological and behavioral surveys [6–9].

RDS is an important recruitment and analysis tools for sampling populations that have no sampling frames and that are linked through social networks. Beginning with a set number of participants, “seeds”, selected purposefully by the research team from the target population, RDS builds a sample through the passing of a coupon from one peer to another. Using a limited number of coupons for each participant limits overrepresentation of those with a higher number of ties to others in the population network. Coupons also limit participants having to provide personal information about their recruits and allows researchers to monitor the recruitment process. Providing ‘incentives’ for those participating in and for recruiting peers into the survey helps ensure ongoing participation and recruitment. Ideally, this process results in long recruitment chains made up of numerous “waves” of recruits [10, 11]. As recruitment chains lengthen, the structure of the sample becomes less dependent on the purposefully selected seeds and increasingly similar to the population being sampled. Once the sample is gathered, statistical adjustments for differential network sizes and recruitment effort are used to produce estimates representative of the sampled population’s network [10–14].

RDS is premised upon several assumptions, most importantly, random walk models [10]. Briefly, these assumptions include (1) reciprocal ties between respondents (i.e., know one another as members of the sampled population); (2) respondents are connected by a single network component; (3) sampling occurs with replacement; (4) respondents provide accurate personal network sizes (i.e., number of relatives, friends, and acquaintances they know from the sampled population); (5) peers are recruited randomly from the recruiter’s network; and, (6) each respondent can recruit at least one peer [11].

Methodologically appropriate RDS surveys are vital for developing national and international policies, guiding service delivery, informing budgets and dictating funding priorities. Quality reporting of data collected and analyzed using RDS methods allows users to assess their usefulness in decision making. However, there is ample potential for bias when using this method, many of which are related to implementation and analytical failures [15–20]. The allure of RDS as a more robust alternative to convenience snowball sampling methods has resulted in partial incorporation of RDS techniques (i.e., the use of coupons) while ignoring some of the more complex aspects which ensure the mitigation of chain referral-related biases [13]. Indeed, numerous published surveys report having used RDS, but present insufficient methodological and analytical information to support this assertion [21].

Building upon the STROBE RDS guidelines [22] which recommend improvements in the reporting of survey data, we extracted peer-reviewed literature that reported using RDS for collecting biological(HIV and other infections) and behavioral data through September, 2013. Specifically, we evaluate a set of general and RDS-specific survey indicators based on the STROBE RDS guidelines [21, 22] to describe the extent, consistency, and changes over time for planning, implementation, and analysis as reported in peer reviewed journals. In addition, we provide reasons why some published surveys were not included in the extraction and examples of surveys that reported using RDS when, in fact, they did not. We hope to build upon other efforts to increase accuracy in conducting RDS and to encourage more thorough and standardized reporting of RDS methods and analysis [4, 22] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Methodological and analytical data from extraction of published articles

| Location of study, citation |

Year of study | Population | Pre-survey assessment |

Sites (num) | Interview methoda |

Seeds at start (num) | Final seeds (num) |

Primary incentive of valueb | Secondary incentive of valueb | Target sample size |

Final sample size |

Max. number of waves | Data collection duration, weeks | Data adjustedc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | ||||||||||||||

| Kenya, Kisumu [23] | 200S | FSW | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 15 | NR | 4.00 | 1.25 | 480 | 481 | 6 | 12 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Abuja [24] | 2010 | MSM | NR | NR | ACASI/SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 194 | 8 | NR | Yes |

| Nigeria, Cross River [25] | 2007 | MSM | NR | 1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | NR | 293 | 293 | 8 | NR | Yes |

| Nigeria, Cross River [26] | 2010 | PWID | NR | >1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 266 | 273 | 9 | 8 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Federal Capital Territory [26] | 2010 | PWID | NR | >1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 266 | 271 | 13 | 8 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Ibadan [27] | 2006 | MSM | NR | NR | IA | 38 | 38 | 4.00 | NR | NR | 1125e | NR | 12 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Ibadan [24] | 2010 | MSM | NR | NR | SA ACASI/SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 210 | 8 | NR | Yes |

| Nigeria, Kaduna [26] | 2010 | PWID | NR | >1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 266 | 196 | 8 | 8 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Kano [26] | 2010 | PWID | NR | >1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 266 | 270 | 12 | 8 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Kano [25] | 2007 | MSM | NR | 1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | NR | 293 | 315 | 9 | NR | Yes |

| Nigeria, Lagos [25] | 2007 | MSM | NR | 1 | IA | 10 | 14 | 4.00 | NR | 293 | 297 | 10 | NR | Yes |

| Nigeria, Lagos [26] | 2010 | PWID | NR | >1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 266 | 191 | 9 | 8 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Lagos [27] | 2006 | MSM | NR | NR | IA | 38 | 38 | 4.00 | NR | NR | 1125e | NR | 12 | Yes |

| Nigeria, Lagos [24] | 2010 | MSM | NR | NR | SA ACASI/SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 308 | 8 | NR | Yes |

| Nigeria, Oyo [26] | 2010 | PWID | NR | >1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 266 | 273 | 8 | 8 | Yes |

| Mauritius [28] | 2009 | PWID | Yes | 2 | IA | 6 | 6 | 7.00 | 3.50 | 500 | 511 | 13 | 12 | Yes |

| Mauritius [29] | 2010 | FSW | NR | 2 | IA | 5 | 5 | 17.50 | 7.00 | NR | 299 | 8 | 2 | Yes |

| Somalia, Hargeisa, Somaliland [30] | 2008 | FSW | Yes | 1 | IA w/HAPI | 6 | NR | 4.00 | 3.00 | 146 | 237 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| South Africa, Durban [31] | 2011 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | 4 | 15 | 5.00 and 5.00 voucher | 5.00 and 5.00 voucher | 200 | 81 | 11 | 17 | NR |

| South Africa, Johannesburg [31] | 2011 | MSM | Yes | 1 | IA or SA | 5 | 14 | 5.00 and 5.00 voucher | 5.00 and 5.00 voucher | 200 | 204 | 15 | 21 | NR |

| South Africa, Soweto [32] | 2008 | MSM | NR | 1 | IA | 15 | 15 | NR | NR | NR | 378 | NR | 30 | Yes |

| South Africa, W. Cape Province [33, 34, 35] | 2006 | Heterosexualmen | Yes | 1 | IA | 8 | 20 | 8.00 phone voucher | 2.70 phone voucher | 430 | 421 | 13 | 15 | Yes |

| South Africa, W. Cape Province [36] | 2008 | Heterosexualmen | Yes | 1 | IA | 19 | 19 | 8.50 phone voucher | 2.85 phone voucher | 430 | 423 | 20 | 12 | Yes |

| South Africa, W. Cape Province [37] | 2007 | Young women | Yes | 1 | SA | 5 | 5 | 8.00 make-up voucher | 2.50 | 270 | 259 | 12 | NR | Yes |

| South Africa, W. Cape Province [38] | 2011 | Heterosexual women | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 15 | 15 | 7.50 grocery voucher | 7.50 grocery voucher | 756 | 845 | 19 | 17 (weekend only) | Yes |

| Sudan, Khartoum [39] | 200S | FSW | NR | 1 | IA | NR | NR | 10.00 | 10.00 | NR | 321 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| Tanzania, Zanzibar [40, 41] | 2007 | MSM | Yes | 1 | IA | 10 | 10 | 3.00 | 1.50 | 500 | 509 | 10 | 12 | Yes |

| Uganda, Kampala [42] | 2008–09 | MSM | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 8 | 14 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 600 | 300 | 11 | 44 | Yes |

| Eastern Mediterranean | ||||||||||||||

| Egypt, Cairo [43] | 2006 | PWID | Yes | 1 | IA | 28 | NR | 7.00 | 5.30 | 406 | 413 | NR | 12 | Yes |

| Iran, Kerman [44] | 2010 | FSW | NR | 1 | IA | 8 | 12 | 4.00 | 2.00 | NR | 177 | NR | 16 | Yes |

| Lebanon, Beirut [45, 46] | 2007–08 | FSW | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6.60 | 2.00 | NR | 135 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Lebanon, Beirut [45] | 2007–08 | MSM | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6.60 | 2.00 | NR | 101 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Lebanon, Beirut [45, 47] | 2007–08 | PWID | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6.60 | 2.00 | NR | 81 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Libya, Tripoli [48] | 2010 | PWID | Yes | 1 | IA | 7 | 7 | 20.00 | 9.00 | NR | 328 | 10 | 8 | Yes |

| Libya, Tripoli [49] | 2010 | MSM | Yes | 1 | IA | NR | 14 | NR | NR | NR | 227 | 15 | NR | Yes |

| Libya, Tripoli [49] | 2010 | FSW | Yes | 1 | IA | NR | 13 | NR | NR | 314 | 69 | 10 | 20 | Yes |

| Morocco, Agadir [50] | 2010–11 | MSM | NR | NR | IA | NR | 10 | 7.00 | 3.50 | NR | 323 | 12 | 12 | Yes |

| Morocco, Marrakesh [50] | 2010–11 | MSM | NR | NR | SA | NR | 8 | 7.00 | 3.50 | NR | 346 | 23 | 12 | Yes |

| Palestine, East Jerusalem [51] | 2010 | PWID | Yes | 1 | IA | NR | 7 | NR | NR | NR | 199 | 12 | NR | Yes |

| Europe | ||||||||||||||

| Albania, Tirana [52] | 2005 | PWID | Yes | 3 | IA | 15 | 15 | 12.00 | 7.00 | NR | 225 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| Albania, Tirana [53] | 2008 | MSM | NR | 1 | IA | 12 | NR | 10.00 | 5.00 | NR | 189 | NR | 5 | Yes |

| Croatia, Zagreb [54, 55, 56] | 2006 | MSM | NR | 1 | SA | 8 | 10 | 18.00 | 9.00 | 400 | 360 | 13 | 14 | Yes |

| Croatia, Zagreb [54] | 2012 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | 10 | 15 | None | 9.60 | 370 | 402 | 13 | 19 | Yes |

| England, Bristol [57, 58] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | CASI | 7 | 7 | 15.00 | 10.00 | NR | 299 | 17 | 6 | Yes |

| England, Bristol [57] | 2009 | PWID | NR | NR | NR | 6 | 6 | NR | NR | NR | 292 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Estonia, Kohtla Jarve [59, 60] | 2005 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 100 | NR | NR | No |

| Estonia, Tallinn [61–63] | 2007 | PWID | Yes | 1 | SA | 5 | 5 | 10.00 food voucher | 5.00 food voucher | NR | 350 | 16 | 7 | No |

| Estonia, Tallinn [63, 64] | 2005–06 | FSW | Yes | 1;; other | SA | 6 | 43 | 10.00 shop voucher | 11.00 shop voucher | NR | 227 | 8 | 28 | Yes |

| Estonia, Tallinn [60, 65] | 2005 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 350 | 8 | NR | Yes |

| Estonia, Tallinn [62] | 2009 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | 6 | 10.00 food voucher | 5.00 food voucher | NR | 327 | NR | NR | No |

| Kazakhstan, Almaty [66] | 2010 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 4 | 4 | 10.00 | 2.50 | 400 | 400 | NR | 16 | Yes |

| Moldova, Balti [67] | 2009–10 | FSW | NR | NR | IA | 5 | 5 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 350 | 359 | 6 | 16 | Yes |

| Moldova, Balti [68] | 2007–08 | PWID | Yes | NR | IA | NR | NR | Items, cash (value NR) | NR | NR | 350e | NR | NR | No |

| Moldova, Balti [69] | 2010 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 5 | 5 | 8.30 | 5.80 | 250 | 209 | 6 | 20 | Yes |

| Moldova, Chisinau [68] | 2007–08 | PWID | Yes | NR | IA | NR | NR | Items, cash (value NR) | NR | NR | 350e | NR | NR | No |

| Moldova, Chisinau [67] | 2009–10 | FSW | NR | NR | IA | 5 | 5 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 350 | 299 | 6 | 16 | Yes |

| Moldova, Chisinau [69] | 2010 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 8 | 8 | 8.30 | 5.80 | 250 | 188 | 6 | 20 | Yes |

| Moldova, Tiraspol [68] | 2007–08 | PWID | Yes | NR | IA | NR | NR | Items, cash (value NR) | NR | NR | 350e | NR | NR | No |

| Montenegro, Podgorica [70] | 2008 | PWID | NR | 1 | SA | 5 | NR | 20.80 | 7.00 | NR | 322 | NR | 12 | Yes |

| Montenegro, Podgorica [71] | 2005 | PWID | NR | 1 | ACASI | NR | NR | 13.00 | 6.00 | NR | 328 | NR | 5 | Yes |

| Russia, Ivanovo [72] | 2010 | PWID | NR | NR | IA | 11 | 11 | Items, food (value NR) | Items, food (value NR) | NR | 300 | NR | 24 | No |

| Russia, Novosibirsk [72] | 2010 | PWID | NR | NR | IA | 10 | 10 | Items, food (value NR) | Item, food (value NR) | NR | 293 | NR | 24 | No |

| Russia, St. Petersburg [73–75] | 2005–08 | PWUD/PWID | NR | NR | CASI | 48; 108 | 156 | 10.00 (items) | items (value NR) | NR | 631; 689 | 14 | 124 | No |

| Russia, St. Petersburg [74, 75] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | CASI | 35 | NR | 10.00 (items) | NR | NR | 387 | NR | 56 | No |

| Serbia, Belgrade [76] | 2010 | Youth | Yes | NR | IA | 8 | 8 | 13.00 | 6.00 | 371d | 270 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| Serbia, Belgrade [71] | 2005 | PWID | NR | 1 | ACASI | NR | NR | 13.00 | 6.00 | NR | 432 | NR | 6 | Yes |

| Serbia, Kragujevac [76] | 2010 | Youth | Yes | NR | IA | 4 | 4 | 13.00 | 6.00 | 370d | 141 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| Ukraine, Poltava [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 4 | 4 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 200 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Khmelnitsky [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 7 | 7 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 200 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Dnipropetrovsk [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | 6 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 113 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Cherkasy [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 3 | 3 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 175 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Donetsk [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | 6 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 400 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Kharkov [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 5 | 5 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 175 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Kherson [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 4 | 4 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 225 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Kirovograd [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 4 | 4 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 175 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Kyiv [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8 | 8 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 400 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Lugansk [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | 6 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 200 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Lutsk [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 4 | 4 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 175 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Lviv [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 7 | 7 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 175 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Mykolaiv [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | 6 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 260 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Odesa [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 6 | 6 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 400 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Simferopol [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 5 | 5 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 265 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Ukraine, Sumy [77] | 2011 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 5 | 5 | 3.00 | 2.00 | NR | 173 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Latin America and Caribbean | ||||||||||||||

| Argentina, Buenos Aires [78, 79] | 2009 | MSM | NR | NR | SA web-based | 16 | 16 | NR | NR | NR | 500 | NR | NR | No |

| Brazil, Belo Horizonte [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Belo Horizonte [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 300 | 289 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Brasilia [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Brasilia [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 300 | 308 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Campinas [84] | 2005–06 | MSM | NR | NR | ACASI | 10 | 30 | NR | NR | NR | 658 | NR | 52 | Yes |

| Brazil, Campo Grande [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Campo Grande [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 150 | 147 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Curitiba [80–83] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Curitiba [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 200 | 201 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Fortaleza [85] | 2008 | Transvestite | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 6.00 food voucher | 3.00 | NR | 304 | NR | 16 | Yes |

| Brazil, Fortaleza [86] | 2005 | MSM | Yes | 2 | IA | 10 | 10 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 400 | 406 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Itajai [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Itajai [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 100 | 90 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Manaus [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Manaus [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 200 | 199 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Recife [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Recife [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 200 | 237 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Rio de Janeiro [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Rio de Janeiro [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 600 | 601 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Salvador [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Salvador [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 300 | 260 | NR | 52 | No |

| Brazil, Santos [80–82] | 2009 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 10.00 | 6.67 | 350 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Brazil, Santos [17, 83] | 2008–09 | FSW | NR | NR | ACASI | 5–10 | NR | Misc. (value NR) | 4.00 | 150 | 191 | NR | 52 | No |

| Dominican Rep., Barahona [87] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 8 | NR | 9.00 | 3.00 | 300 | 281 | 12 | 8 | Yes |

| Dominican Rep., La Altagracia [87] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 7 | NR | 9.00 | 3.00 | 300 | 270 | 11 | 8 | Yes |

| Dominican Rep., Santiago [87] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 6 | NR | 9.00 | 3.00 | 300 | 327 | 13 | 8 | Yes |

| Dominican Rep., Santo Domingo [87] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | NR | IA | 7 | NR | 9.00 | 3.00 | 500 | 510 | 15 | 8 | Yes |

| El Salvador, San Miguel [88, 89] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | NR | CASI w/interviewer | 5 | 5 | 4.00 as items | 2.70 (items) | 200 | 195 | 19 (2 cities) | 16 | Yes |

| El Salvador, San Salvador [89] | 2008 | FSW | NR | 1 | CASI w/interviewer | 10 | 10 | Items (value NR) | Items (value NR) | NR | 787e | NR | NR | No |

| El Salvador, San Salvador [88, 89] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | NR | CASI w/interviewer | 11 | 11 | 4.00 as items | 2.70 (items) | 600 | 596 | 19 (2 cities) | 16 | Yes |

| El Salvador, Sonsonate [89] | 2008 | FSW | NR | 1 | CASI w/interviewer | 5 | 5 | Items (value NR) | Items (value NR) | NR | 787e | NR | NR | No |

| Honduras, Comayagua [90] | 2006 | FSW | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 5 | 5 | Purse (value < 2.00) | Items (value 3.50) | 200 | 182 | 11 | 8 | Yes |

| Honduras, La Ceiba [90] | 2006 | FSW | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 7 | 7 | 200 | 211 | 7 | 8 | Yes | ||

| Honduras, San Pedro Sula [90] | 2006 | FSW | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 7 | 7 | 200 | 198 | 13 | 8 | Yes | ||

| Honduras, Tegucigalpa [90] | 2006 | FSW | Yes | 1 | ACASI | 5 | 5 | 200 | 204 | 7 | 10 | Yes | ||

| Peru, Lima [91] | 2012 | Transwoman | Yes | 6 | SA | 8 | 11 | 7.00 | NR | 420 | 450 | NR | 16 | Yes |

| North America | ||||||||||||||

| Mexico, Juarez [92–96] | 2005 | PWID | NR | 1 | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 204 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| Mexico, Juarez [97] | 2005 | PWID | NR | 1 | SA | 9 | 17 | 20.00 | 5.00 | 200 | 197 | 8 | 2 | Yes |

| Mexico, Tijuana [92–96] | 2005 | PWID | NR | 3 | SA | 15 | 15 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 200 | 207 | 8 | 8 | Yes |

| Mexico, Tijuana [92–102] | 2006–07 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 32 | NR | 20.00 | NR | NR | 1056 | NR | 52 | Yes |

| USA, Appalachia [103] | NR | PWUD | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 50.00 | 10.00 | NR | 503 | NR | NR | No |

| USA, Atlanta [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 561 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Baltimore [104] | 2002–04 | Youth PWID | NR | NR | ACASI, w/w/out interviewer | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 736 | NR | 88 | No |

| USA, Baltimore [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 722 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Baltimore [105] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | CAPI | 20 | 20 | 20.00 | 10.00 | NR | 670 | NR | 20 | Yes |

| USA, Boston [106, 107] | 2008 | MSM | NR | 2 | SA | 8 | 21 | 50.00 | 10.00 | NR | 197 | NR | 24 | No |

| USA, Boston [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 475 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Chicago [104] | 2002–04 | Youth PWID | NR | NR | ACASI, w/w/out interviewer | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 586 | NR | 88 | No |

| USA, Chicago [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 542 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Dallas [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 570 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Denver [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 532 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Detroit [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 545 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Ft. Lauderdale [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 384 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Houston [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 596 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Houston [108] | 2006–07 | High risk heterosexuals | Yes | 1 | CAPI | NR | NR | 40.00 | 10.00 | 750 | 939 | NR | 36 | Yes |

| USA, Las Vegas [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 334 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Los Angeles [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 602 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Los Angeles [75, 109–111] | 2005–06 | PWUD/PWID/MSM | NR | 1 | ACASI | 25 | 25 | 50.00 | 20.00 | NR | 426 | 21 (both phases) | 52 | Yes |

| USA, Miami [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 607 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Nassau [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 529 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, New Haven [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 534 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Las Cruces [97] | 2005 | PWID | NR | 1 | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 100 | NR | 8 | No |

| USA, New York City [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 508 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, New York City [112] | 2009 | PWID | Yes | NR | SA | NR | 3 | NR | NR | NR | 488 | NR | 8 | Yes |

| USA, New York City [113–118] | 2006–07 | High risk heterosexuals | Yes | NR | SA | 8 | NR | 30.00 | 11.00 | NR | 850 | NR | NR | No |

| USA, New York City [1, 119, 120] | 2004 | PWUD | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 20.00 | 10.00 | NR | 448 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Newark [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 440 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Norfolk [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 499 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Oakland [121] | 2011–12 | High risk/HIV pos. African American | Yes | 4 | SA | 48 | NR | 10.00 gift card | Varied | NR | 243 | NR | 52 | Yes |

| USA, Philadelphia [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 539 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, San Diego [122] | 2009–10 | PWID | NR | NR | ACASI | NR | NR | NR | 10.00 | NR | 510 | NR | 64 | No |

| USA, San Diego [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 539 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, San Francisco [123] | 2007–08 | MSM | Yes | 1 | CAPI | 10 | 10 | 40.00 | 10.00 | NR | 256 | 18 | 24 | Yes |

| USA, San Francisco [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 581 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, San Juan [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 573 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Seattle [124] | 2009 | PWID | NR | 1 | IA | 6 | 6 | 40.00 | 10.00 | NR | 497 | 16 | 16 | Yes |

| USA, Seattle [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 400 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, St. Louis [6] | 2005–06 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8–10 | NR | 25.00 | 10.00 | NR | 525 | NR | NR | Yes |

| USA, Wash. DC [125] | 2006–07 | High risk heterosexuals | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | NR | 35.00 | 10.00 | NR | 750 | NR | 44 | Yes |

| USA, Wash. DC [126] | 2009 | PWID | NR | 1 | SA | NR | NR | 30.00 | 10.00 | NR | 553 | NR | 16 | Yes |

| USA, Texas, El Paso [97] | 2006 | PWID | NR | 1 | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 155 | NR | 24 | Yes |

| South East Asia | ||||||||||||||

| Bangladesh, Dhaka [127] | 2006 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | 5 | 8 | 2.14 | 1.43 | 530 | 531 | 9 | 11 | Yes |

| India, Bishenpur District, Manipur [128] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 400 | 420 | NR | NR | Yes |

| India, Chennai [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 2 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Churachandpur District, Manipur [128] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 400 | 419 | NR | NR | Yes |

| India, Coimbatore [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Dimapur District, Nagaland [130] | 2006 | FSW | NR | NR | SA | 10 | 10 | NR | NR | 400 | 426 | 11 | 8 | No |

| India, Dindigul [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Erode [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Goa [131, 132] | 2005 | FSW | Yes | NR | SA | 59 | 59 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 318 | 326 | 6 | 52 | Yes |

| India, Kanyakumari [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Madurai [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Mumbai and Thane Districts [128] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 400 | 376 | NR | NR | Yes |

| India, Nagapattinam [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Nilgiris [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Perambalur [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Phek District, Nagaland [128] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 400 | 440 | NR | NR | Yes |

| India, Pudukkottai [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Ramanathapuram [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Salem [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Sivaganga [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Thanjavur [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Tiruchy [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Tirunelveli [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Thiruvarur [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Tuticorin [129] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | NR | 19 | 6.00 | None | NR | 721e | 3 | 8 | No |

| India, Wokha District, Nagaland [128] | 2006 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 400 | 420 | NR | NR | Yes |

| Pakistan, Abbottabad [133] | 2007 | MTSW | Yes | 2 | IA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 103 | NR | 8 | No |

| Pakistan, Abbottabad [133] | 2007 | FSW | Yes | 2 | IA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 109 | NR | 8 | No |

| Pakistan, Lahore [133] | 2007 | FSW | Yes | 3 | SA | 3 | NR | NR | NR | 726 | 730 | 5 | 12 | Yes |

| Pakistan, Rawalpindi [133] | 2007 | MTSW | Yes | 2 | IA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 812 | NR | 8 | No |

| Pakistan, Rawalpindi [133] | 2007 | FSW | Yes | 2 | IA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 431 | NR | 8 | No |

| Thailand, Bangkok [134] | 2007 | FSW | NR | 3 | ACASI, with/w/out interviewer | 15 | 15 | 11.80 | 1.50 | NR | 707 | 3 | 12 | Yes |

| Western Pacific | ||||||||||||||

| China, Beijing [135] | 2009 | MSM | NR | 1 | ACASI | 7 | 7 | 4.50 | 3.00 | NR | 500 | NR | 8 | No |

| China, Beijing [3] | 2004 | MSM | NR | 1 | SA | 1 | 1 | None | 2.10 | NR | 325 | 15+ | 14 | Yes |

| China, Beijing [3, 136] | 2005 | MSM | NR | 1 | SA | 10 | 10 | None | 2.10 | NR | 427 | 15+ | 16 | Yes |

| China, Beijing [3] | 2006 | MSM | NR | 1 | SA | 8 | 8 | None | 2.10 | NR | 540 | 15+ | 14 | Yes |

| China, Beijing [137] | 2009 | MSM | NR | 1 | CAPI | 7 | 8 | 5.00 | 3.20 | NR | 501 | 13 | 8 | Yes |

| China, Chongqing [138] | 2009 | MSM | NR | NR | CASI | 7 | 7 | 4.50 | 3.00 | NR | 503 | 14 | 12 | Yes |

| China, Guangdong [139] | 200S | PWID | Yes | 1 | SA | 6 | 7 | 7.50 | 3.00 | 238 | 290 | 11 | 16 | Yes |

| China, Guangdong [140] | NR | FSW | NR | 1 | IA or CASI | 4 | 4 | NR | NR | NR | 320 | 16 | NR | Yes |

| China, Guangzhou [141] | 2008 | MSM | NR | 1 | SA | 13 | 13 | 5.00, gift/cash | 1.50 | NR | 379 | 14 | 16 | Yes |

| China, Jinan [142, 143] | 2007 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | 9 | 9 | None | NR | 428 | 428 | NR | 20 | Yes |

| China, Jinan [142, 143] | 2008 | MSM | Yes | 1 | SA | 5 | 5 | None | NR | 500 | 500 | NR | 12 | Yes |

| China, Jinan [144] | 2008 | FSW | Yes | 1 | SA | 7 | 7 | 7.30 | 2.90 | NR | 363 | 25 | 24 | Yes |

| China, Jinan [144] | 2009 | FSW | Yes | 1 | SA | 4 | 4 | 7.30 | 2.90 | NR | 432 | 21 | 20 | Yes |

| China, Liuzhou [145, 146] | 2009–10 | FSW | Yes | 1 | SA | 7 | 8 | 14.00 | 7.00 | 380 | 583 | 20 | 13 | Yes |

| China, Nanjing [147] | NR | MSM | NR | 1 | NR | 9 | 9 | 4.00 phone card | NA | NR | 416 | NR | NR | No |

| China, Shandong [148] | 2007–08 | Money boys | NR | NR | SA | 16 | NR | NR | NR | 120 | 118 | NR | NR | No |

| Indonesia, Bandung [149] | 2007 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8 | NR | NR | 4.00 | 250 | 250 | NR | 16 | No |

| Indonesia, Surabaya [149] | 2007 | PWID | NR | NR | SA | 8 | NR | NR | 4.00 | 250 | 250 | NR | 16 | No |

| Vietnam, Cam Ranh [150] | 2005 | MSM | NR | 1 | NR | 2 | NR | 1.90 | 0.95 | 300 | 295 | 5 | 12 | No |

| Vietnam, Dien Khanh [150] | 2005 | MSM | NR | 1 | NR | 2 | NR | 1.90 | 0.95 | 300 | 295 | 5 | 12 | No |

| Vietnam, Hai Phong [150] | 2004 | FSW | NR | NR | SA | 20 | 25 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 200 | 215 | NR | 12 | Yes |

| Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City [150] | 2004 | FSW | NR | NR | SA | 20 | 24 | 4.00 | 1.50 | 400 | 413 | NR | 12 | Yes |

| Vietnam, Nha Trang [150] | 2005 | MSM | NR | 1 | NR | 2 | NR | 1.90 | 0.95 | 300 | 295 | 5 | 12 | No |

| Vietnam, Ninh Hoa [150] | 2005 | MSM | NR | 1 | NR | 2 | NR | 1.90 | 0.95 | 300 | 295 | 5 | 12 | No |

| Vietnam, Van Ninh [150] | 2005 | MSM | NR | 1 | NR | 2 | NR | 1.90 | 0.95 | 300 | 295 | 5 | 12 | No |

NR not reported, N/A not applicable, IA interviewer administered, SA self-administered, CASI computer assisted structured interview, ACASI computer assisted structured interview

Unless otherwise stated, ACASI and CASI are self-administered

All figures are in US Dollar

Adjusted is when at least one of the published articles analyzed frequency data using either the reciprocity model based estimator (RDS I) (Salganik and Heckathorn [13]), dual component estimator (RDSI DC) (Heckathorn [12]), probability-based estimator (RDSII) (Volz and Heckathorn, [14]) or successive sampling estimator (Gile [11]). In the cases data were reported as “weighted” but neither cited an appropriate reference nor an appropriate software (RDSAT, RDS Analyst and in some cases Stata 11 [Schonlaau and Liebau, 2012-RDSI Only]), R and Matlab, they were considered not providing sufficient information to determine correct analysis

Target sample size combined for Serbia (2010; Belgrade and Kragujevac)

Final sample size combined for Nigeria (2006; Ibadan and Lagos), Moldova (2007–08; Balti, Chisinau and Tiraspol), El Salvador (2008; San Salvador and Sonsonate), and India (2008;Chennai, Coimbatore, Dindigul, Erode, Kanyakumari, Madurai, Nagapattinam, Nilgiri, Perambalur, Pudukkottai, Ramanathapuram, Salem, Sivaganga, Thanjavur, Tiruchy, Tirunelveli,Thiruvarur, and Tuticorin)

Methods

Literature Search

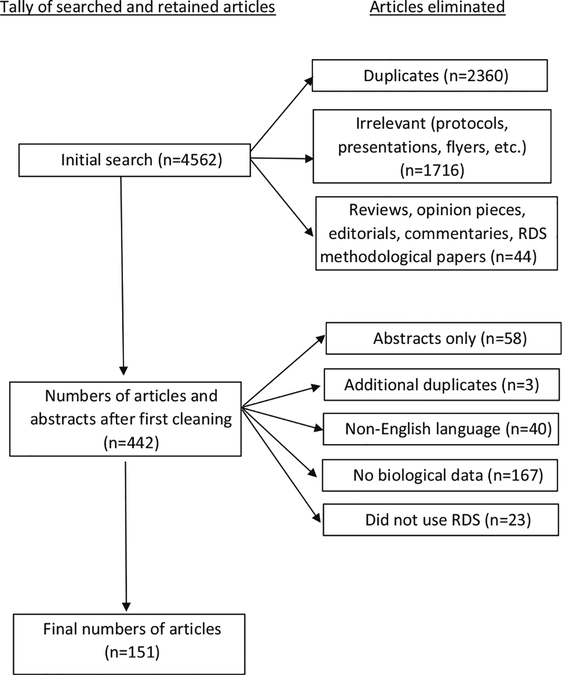

We examined peer-reviewed literature published in physical or on-line journals that reported using RDS and were either accessible through September, 2013, or were identified from a previously conducted search [22]. Searches were conducted using MEDLINE (1997–2013), EMBASE (1997–2013), and Global Health (1997–2013). Search terms included “respondent driven”, “respondent-driven” or “RDS”. The original extraction included surveys in any country, in any language, and among any survey population that reported using RDS (n = 4562). Articles excluded in the initial extraction were those that were duplicates (n = 2360), irrelevant (e.g., protocols, presentations, flyers, etc.; n = 1716) and either reviews, opinion pieces, editorials, commentaries and papers strictly addressing RDS methodology (n = 44, i.e., those not intending to report population based estimates). This resulted in a total of 442 articles and abstracts. We further refined our search by eliminating abstracts (n = 58) and publications that were either duplicated (n = 3), non-English (n = 40), without biological data (n = 167), or claimed to, but did not, use RDS (n = 23). When there were a number of publications for a single survey, all related publications were reviewed to update the extraction sheet. This resulted in 151 articles representing 222 surveys (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

RDS extraction process

Categorizing Documents and Extraction

We selected and extracted key data from 151 journal articles and entered them into a master table in Excel® into rows specific to the survey(s) described. Journal data entered into the table were organized into seven sub-tables based on WHO categorizations of regions: Africa, Eastern Mediterranean (EM), Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), North America, South-East Asia (SEA), and Western Pacific. We extracted information considered essential for assessing RDS-specific survey quality as reported in Malekinejad et al. [4], Montalegre et al. [5] and White et al. [21, 22]. The indicators reviewed included those informing survey design and implementation and analysis. Indicators informing survey design and implementation are the survey year, eligibility criteria, specimen type collected for biological testing, whether pre-survey research was conducted, number of recruitment sites, interview method, number of seeds at the start and end (and whether seeds were added or failed during data collection) of the survey, amount or type of primary and secondary incentives (USD), calculated target and final sample size, design effect used for sample size calculation, maximum number of waves, duration of data collection (in weeks), and maximum number of coupons distributed to each recruiter. Indicators informing analysis are whether equilibrium or convergence was assessed, whether data were adjusted for network size, software used, and the citation and estimator used for adjustment. The rationale for selecting these indicators, including their usefulness in any survey versus specifically for RDS surveys, are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reporting of essential information to interpret survey quality, number, percentage, median and range (2004–2012) and rationale for reporting

| Indicators | Percent of publications reporting information | Values of reported information | Rational for reporting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (222) | % | Median (range) | ||

| Year of survey | 219 | 99 | - | Useful for any survey to identify how current data are, to plan future surveys and to compare data from other surveys |

| Eligibility criteria (minimum of behavior description)c | 222 | 97 | - | Useful for any survey to determine the denominator being measured, to know measurement for the construction of the social network question needed for RDS analysis. Provides readers with possible criteria to use in different populations and settings; allows for comparison of data across countries |

| Type of specimen collected for biological testingc | 193 | 87 | - | Useful for any survey. Informs readers about the types of testing being conducted in different populations and settings |

| Pre-survey research conducted | 88 | 40 | - | Useful for any survey. Informs readers about the survey planning process, especially whether attempts were made to assess the underlying network structure of the population |

| Number of recruitment sites per survey area | 95 | 43 | 1 (1–6) | Especially useful in RDS as it alerts readers to the possible violation of the network being one complete component if participants at each site are not connected; informs readers about the possible clustering (or diffusion) of the sample |

| Interview method | 210 | 94 | - | Useful for any survey. Provides information about the level of confidentiality in the survey (i.e., ACASI may provide more confidentiality) and informs readers about the different types of methods used for interviewing hidden populations in RDS surveys |

| Number of seeds at the start of the survey | 62 | 28 | 7.5 (1–48) | Specifically useful for RDS surveys. Informs readers about whether many seeds were added during data collection and the number of seeds in relation to the sample size and number of waves (too many seeds may result in too few waves needed to reduce seed dependence, adding too many seeds may be an indication that the population is not well networked); provides parameters for readers about seeds needed in different populations and settings |

| Whether seeds were added during data collection | 17 | 8 | 5 (1–37) | |

| Whether seeds failed during data collection | 14 | 6 | 4 (1–24) | |

| Number of seeds by the end of the survey | 121 | 54 | 10 (1–156) | |

| Amount or type of primary incentive (USD) | 186 | 84 | 3 (1.9–5)a | Specifically useful for RDS surveys. Provides readers with parameters about amounts used in different populations and settings; provides an indication of potential bias during recruitment (if incentives are too high, more people may enroll who are not eligible) |

| Having no primary incentive | 6 | 3 | - | |

| Amount or type of secondary incentive (USD) | 177 | 80 | 10 (0.95–20)b | |

| Having no secondary incentive | 18 | 8 | - | |

| Calculated target sample size | 89 | 40 | 300 (100–756) | Useful for any survey. Indicates if an original sample size was calculated and if that sample size was reached in order to ensure sufficient power and confidence for data analysis. Provides readers with parameters about sample sizes used in different populations and settings. Specific for RDS surveys: combining multiple survey sites is often a violation of the network being one network component |

| Final sample size | 212 | 95 | 325 (100–1056)c | |

| Final sample size for multiple cities combined | 28 | 12 | - | |

| Design effect used for sample size calculationd | 50 | 22 | 2 (1.3–3) | Design effects, currently recommended to be at least 2 [16, 151, 152], are important for calculating a sufficient sample size to account for RDS not being a traditional random sample |

| Maximum number of waves | 95 | 43 | 9 (3–21) | Specific to RDS surveys: useful to assess seed dependence |

| Duration of data collection (in weeks) | 139 | 63 | 12 (2–124) | Informs readers of the time needed to gather samples of different sizes from different populations and settings; alerts readers of unusual recruitment lengths that may impact representativeness of the sample |

| Maximum number of coupons distributed to each recruiterd | 163 | 73 | 3 (2–7) | Specific to RDS surveys: The number of coupons used are normally three [7], but some surveys have used more or fewer. Analysis does not account for branching induced by the number of coupons provided to each participant so fewer coupons, when possible, is useful to mimic a random walk process |

| Whether equilibrium or convergence was assessedd | 44 | 20 | Specific to RDS surveys: Informs readers of seed dependence and is a diagnostic to assess bias | |

| Whether data were adjusted for network size | 157 | 70 | - | Specific to RDS surveys: Informs readers of the extent to which RDS was fully utilized, resulting in the ability to assess whether the survey may represent the network of the population from which the sample was gathered |

| Software used to adjust datad | 162 | 73 | - | Specific to RDS surveys: There are limited software packages available for analyzing RDS data. Analyzing RDS data in more popular, preexisting software (i.e., STATA, SPSS) may not eliminate RDS specific biases |

| Citation for adjustmentd | 59 | 26 | - | Specific to RDS surveys: Given the evolvement of the estimators for the analysis of RDS data, this is useful for providing information about the assumptions supporting the adjustments |

| Heckathorn [10, 153]d | 19 | 32 | - | |

| Salganik and Heckathorn [12]d | 28 | 47 | - | |

| Heckathorn [11]d | 10 | 17 | - | |

| Volz and Heckathorn [13]d | 7 | 12 | - | |

| Gile [154]d | 4 | 7 | - | |

| Estimator used for adjustmentd | 10 | 4 | - | |

| Whether seeds were discarded during analysis | 31 | 14 | - | Some studies either did not collect data from seeds or did not include seeds data the analysis, which could likely result in the sample having addition seeds (analysis would assume wave 1 participants are seeds) thereby potentially impacting seed dependence and biasing the final estimate |

Among those that reported a value (n = 166)

Among those that reported a value (n = 152)

Among those that reported a sample size for an individual city (n = 185)

Not presented in Table 1

Analysis

Frequencies were used to characterize the surveys and their contents. We conducted robust and logistic regressions of survey start year and pre-survey research, eligibility age, number of seeds at the start and end of survey, survey duration, final sample size, estimated design effect, length of longest recruitment chain, and adjustment of RDS to assess linear trends in the value (and for reporting having conducted pre-survey research or adjusted RDS data) of these indicators over time. Design effects were calculated for surveys that presented a point estimate for HIV prevalence, 95 % confidence intervals and the final sample size. The calculation for design effects consisted of dividing the widths of the confidence interval by two, dividing again by 1.96 (the standard normal value corresponding to a central area of 95 %), and squaring the final number.

Results

The identified published articles of RDS surveys were conducted in the following WHO regions: 21 from Africa (28 surveys), 12 from EM (11 surveys), 30 from Europe (44 surveys), 17 from LAC (37 surveys), 41 from North America (45 surveys), 12 from SEA (32 surveys), and 18 from the Western Pacific (25 surveys). Extracted surveys included 85 among PWID, 78 among MSM and 38 among FSW. Surveys of other groups included people who use and/or inject drugs (n = 2), male sex workers (n = 3), high-risk heterosexuals (n = 7), transgender (n = 2), and youth (n = 3). The remaining surveys were of mixed groups such as youth PWID (n = 2), people who use and/ or inject drugs together (n = 1) and MSM who use and/or inject drugs (n = 1).

Assessing Reports of Survey Quality

Survey data extracted from published articles included in this review were used to assess whether RDS recruitment and analysis were conducted, but the details provided for these surveys varied across articles. For instance, all published surveys reported basic implementation information such as the city, country and the population sampled, and 99 % reported the survey year (Table 2). Over 90 % of surveys reported the interview technique (e.g., face-to-face questionnaire, computer-assisted self-interviews, etc.) (94 %), final sample size (95 %) and at least the behavioral component of the eligibility criteria (97 %). Eighty-four percent reported the primary and 80 % reported the secondary incentive amounts or types, and 73 % reported the maximum number of coupons given to each recruiter. Sixty-three percent reported the data collection duration, 40 % reported whether pre-survey research was conducted, 43 % reported the number of recruitment sites used and the maximum number of waves, 40 % reported the target sample size, 22 % reported the design effect used for calculating the sample size. For those surveys that presented both calculated and final sample sizes (n = 77, 35 %), the median percentage difference was 1.0 (range 0.2–1.6). There was no significant difference in this measure over time by population or among all populations combined.

Seventy percent reported whether data were adjusted for network size, 73 % reported the type of software used to adjust data (74 % of which used RDS Analysis Tool [RDSAT]) and 26 % cited the statistical adjustment, among which 47 % cited Salganik and Heckathorn [12], 32 % cited Heckathorn [10] and/or 2002, 17 % Heckathorn [11], 12 % Volz and Heckathorn [13] and 7 % Gile [14, 154]. Only 20 % of surveys reported whether equilibrium or convergence was assessed and 4 % reported which estimator was used for their statistical adjustment. Thirty-one surveys (14 %) specifically reported discarding seeds from their analysis.

Design Effects for HIV

Of the 222 publications reviewed, 185 reported HIV prevalence point estimates above 0, 136 included 95 % confidence bounds, and 210 reported final sample sizes. Ninety-five surveys (42.7 %) included all three elements to enable calculation of the estimated design effect for HIV prevalence. Four (4.2 %) had a design effect less than 1.0, 28 (29.5 %) had a design effect of 1.0, 46 (48.4 %) had a design effect of 2. The remaining design effects were as high as 5.9, indicating that a larger sample size was needed to estimate HIV prevalence.

Assessing Changes over Time

In assessing changes over time (Table 3), we found significant decreases in values for eligibility age, final number of seeds, and final sample size (p \ 0.01, for all) and significant increases in the reporting of pre-survey research and values of design effects to calculate the target sample size (p \ 0.01). There were no significant changes in values for survey duration even when adjusting for target population and final sample sizes. Nor were there significant changes by year for survey duration, length of longest recruitment chain and reporting of having adjusted RDS data.

Table 3.

Annual rate of change over time (2004–2012) based on robust regression of values and reported information

| Variable | Change (95 % CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Reporting having conducted pre-survey research | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) | 0.01 |

| Reporting having adjusted RDS data | 0.03 (0.00, 0.6) | 0.09 |

| Lower eligibility age value | −0.14 (−0.20, −0.07) | 0.00 |

| Number of seeds at start of survey | −0.14 (−0.43, 0.14) | 0.33 |

| Number of seeds at end of survey | −0.31 (−1.86, −0.66) | 0.00 |

| Survey durations | 0.15 (−0.35, 0.66) | 0.55 |

| Final sample sizes | −29.14 (−39.56, −8.73) | 0.00 |

| Sizes of estimated design effects | 0.07 (0.02, 0.12) | 0.01 |

| Length of longest recruitment chain | 0.29 (−0.39, 0.97) | 0.40 |

Discussion

Reporting on details of survey design, implementation, and analysis is essential for assessing the quality of RDS surveys and findings. It is important to adequately describe both the methodological and analytical aspects of RDS in any publication. The majority of surveys reported the most essential information such as survey city, country, year, population sampled, interview method, and final sample size. Given that all surveys reported collecting biological specimens, it is surprising that 13 % did not provide information about specimen collection and testing methods. Gaps in reporting RDS methodological and analytical information made it difficult to assess survey quality and the strength of results. RDS does not work in all situations and challenges in meeting assumptions should be described. For instance, only 43 % of surveys reported the maximum number of waves and 20 % reported assessment of equilibrium or convergence, information needed to assess potential biases. Among those surveys reporting their maximum number of waves, some reported having only a maximum of three waves, indicating that the survey results were likely biased by the non-randomly selected seeds.

Pre-survey research has become increasingly cited as being essential to conducting RDS surveys [7, 15, 22, 155], and more publications over time were found to provide information about having conducted some pre-survey research. Because RDS samples a social network, pre-survey research is imperative to understand the underlying network structure of the sampled population. If the sampled network is fragmented or has isolated sub-groups, the chances of sampling more than one network are higher, possibly resulting in unstable estimates [15]. Furthermore, pre-survey research data can help investigators plan survey logistics (i.e., types and number of seeds) and encourage participation by learning about which survey procedures are most acceptable to the target population [7]. We recommend that all surveys using RDS conduct pre-survey research to evaluate social networks, as well as to assess the feasibility of using RDS in a particular population.

Although 70 % of surveys reported whether data were adjusted for network size and 73 % reported the software used to adjust those data, few cited the adjustment procedure and even fewer reported the estimator used. There are currently at least five different estimators for adjusting RDS data [156]. Given that many of the reviewed articles were written before the existence of some estimators, it is understandable that earlier publications did not cite the estimator used for analysis. Forthcoming publications should cite the estimator since knowing this information will allow readers to know how adjustments were made, if they were made properly, and the assumptions supporting those adjustments.

Several publications reported discarding seeds from analysis. While it has been written that “seeds are eliminated from analysis” [13, 153], this is not to say that seeds should be manually eliminated from a dataset. The RDS-I and RDS-II estimators [11–13, 153] use a matrix of recruits and recruiters whereby data from the recruits are necessary for calculating inclusion probabilities used to derive final estimates. Even though the seeds do not technically show up in the probability matrix since they were never recruited by their peers, their data are nonetheless necessary for establishing the placement of the seeds’ recruits in the matrix. We recommend that seeds remain in the dataset during all analyses and that the final reported sample includes the seeds.

We found an increase over time in surveys reporting design effects, an element in the sample size calculations to account for RDS not being a simple random sample. Although recent publications have found that design effects of 3 or 4 would be optimal, in most situations, a design effect of 2 is often recommended [16, 151, 152]. Because operational constraints, such as limited financial resources, often preclude large sample sizes for some RDS surveys, using a design effect greater than 2 may result in unfeasibly large sample sizes. Post-hoc design effects on key variables can help determine if sample sizes were large enough for the analysis and inform sample size calculations for follow-up surveys of the same population. As such it is useful for publications to include point estimates, 95 % confidence intervals and final sample sizes to allow for the post hoc estimation of design effects.

Equilibrium or convergence was reported in only 20 % of the articles reviewed. Equilibrium, the term most often used when referring to RDS surveys, measures the progression of waves to determine when the proportion for a characteristic approaches and remains stable in relation to the final sample statistic [10]. Convergence, a more sensitive measurement, measures the progression of enrolling subjects to determine when the proportion for a characteristic approaches and remains stable in relation to the adjusted estimate [15]. Nevertheless, the assessment of either equilibrium or convergence is useful for determining seed dependence, a typical bias found in chain referral sampling methods, and should be reported for publications reporting population estimates from RDS surveys [22].

While most surveys reported a minimum eligibility age of 18 years (n = 150), we found the minimum age decreased over time. Collecting HIV and other biological and behavioral data from younger key populations is important given they are disproportionately affected by HIV worldwide and are comprising a high percentage of new HIV infections [9, 157].

Our review has limitations. As in any systematic review, we are restricted by the completeness of our publication search and whether investigators published their surveys in peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, we only included surveys that collected biological data leaving room for further evaluation of those surveys that reported using RDS and did not collect biological data. The number of peer-reviewed articles of RDS surveys is far fewer than the actual number of surveys conducted. Key data were missing from articles, an important finding in itself which supports the need to uniformly report results from RDS surveys, which limited the scope of our analyses and introduced uncertainty into some of our other findings [22]. We excluded articles clearly stating they either used RDS ‘recruitment’ only or did not fulfill necessary features of the method; however, we may have included some surveys that did not incorporate all RDS methodological and analytical features, given their incomplete reporting. In those instances, we classified the surveys as using RDS and included them in the extraction. Several of the 23 articles claiming to use RDS, but did not, reported using a ‘modified’ or ‘mixed methods’ RDS. However, they did not provide conclusive evidence such as the collection and use of personal network size data, recruitment ties (who recruited whom), coupon quotas, and multiple recruitment waves. In several extracted publications, significant limitations were reported, including unprepared staff, numerous ineligible persons trying to participate, closing or moving survey sites during data collection, overly high (possible indication of enrollment of ineligible participants) or low incentives, overcrowding at the interview site, failure to recruit important population subgroups (i.e., females in PWID surveys, older MSM), incorrect or no social network question, and early survey termination due to finances or community disturbances [3, 34, 41, 55, 86, 127, 158]. Presenting key limitations is useful for interpreting findings and should be included in all publications presenting data from RDS surveys.

The majority of published surveys were from North American and Europe; it would be useful to see more publications of RDS survey results from other regions. Not only could experiences from these different settings help researchers improve survey methods and analysis, but the results themselves could help policy makers, donors, and service providers to improve responses to HIV and other infection risk. Future publications of biological and behavioral surveys using RDS should provide a minimum set of parameters in order for readers to assess specific methodological, analytical and testing procedures, and to make determinations of the overall quality of these surveys.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kate Orroth for conducting the literature search for the STROBE-RDS Guidelines and allowing us to use it for this analysis.

Funding This Project has been supported in part by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). RGW is funded the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement that is also part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union (MR/J005088/1, G0802414), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (TB Modelling and Analysis Consortium: OPP1084276, and SA Modelling for Policy: #OPP1110334) and UNITAID (4214-LSHTM-Sept15; PO #8477-0-600).

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Perlis T, Hagan H, Abdul-Quader A, Heckathorn DD, et al. Convergence of HIV seroprevalence among injecting and non-injecting drug users in New York City. AIDS. 2007;21(2):231–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston LG, Sabin K, Hien MT, Huong PT, Mai TH, Pham TH. Assessment of respondent driven sampling for recruiting female sex workers in two Vietnamese cities: Reaching the unseen sex worker. J Urban Heal. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma X, Zhang Q, He X, Sun W, Yue H, Chen S, et al. Trends in prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men: results of 3 consecutive respondent-driven sampling surveys in Beijing, 2004 through 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(5): 581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malekinejad M, Johnston LG, Kendall C, Kerr LRFS, Rifkin MR, Rutherford GW. Using respondent-driven sampling methodology for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in international settings: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4 Suppl):S105–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montealegre JR, Johnston LG, Murrill C, Monterroso E. Respondent driven sampling for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in Latin America and the Caribbean. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2313–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lansky A Assessing the assumptions of respondent-driven sampling in the national HIV behavioral surveillance system among injecting drug users. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston LG. Introduction to respondent-driven sampling. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMRPUB_2013_EN_1539.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV. 2011. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2011/20110518_Accessed 15 Jun 2015.

- 9.UNICEF, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNAIDS. Young key populations at higher risk of HIV in Asia and the Pacific: making the case with strategic information. Bangkok: UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office; 2013. http://www.unicef.org/eapro/Young_key_populations_at_high_risk_of_HIV_in_Asia_Pacific.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heckathorn DD. Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: analyzing continuous variables and controlling for differential recruitment. Sociol Methodol. 2007;37(1):151–207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34(1):193–240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volz E, Heckathorn DD. Probability based estimation theory for respondent driven sampling. J Off Stat. 2008;24(1):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gile KJ. Improved inference for respondent-driven sampling data with application to HIV prevalence estimation. J Am Stat Assoc. 2011;106(493):135–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gile KJ, Johnston LG, Salganik MJ. Diagnostics for respondent-driven sampling. J R Stat Soc. 2015;1(1):241–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salganik MJ. Variance estimation, design effects, and sample size calculations for respondent-driven sampling. J Urban Heal. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i98–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szwarcwald CL, de Souza Júnior PRB, Damacena GN, Junior AB, Kendall C. Analysis of data collected by RDS among sex workers in 10 Brazilian cities, 2009: estimation of the prevalence of HIV, variance, and design effect. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(3 Suppl):S129–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCreesh N, Frost SDW, Seeley J, Katongole J, Tarsh MN, Ndunguse R, et al. Evaluation of respondent-driven sampling. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):138–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goel S, Salganik MJ. Assessing respondent-driven sampling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6743–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wejnert C An empirical test of respondent-driven sampling: Point estimates, variance, degree measures, and out-of-equilibrium data. Sociol Methodol. 2009;39:73–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hafeez S A review of the proposed STROBE-RDS reporting checklist as an effective tool for assessing the reporting quality of RDS studies from the developing world. London: 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.White RG, Hakim AJ, Salganik MJ, Spiller MW, Johnston LG, Kerr L, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology for respondent-driven sampling studies: “STROBE-RDS” statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(12): 1463–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenhoudt HM, Langat L, Menten J, Odongo F, Oswago S, Luttah G, et al. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among Female Sex Workers in Kisumu, Western Kenya, 1997 and 2008. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vu L, Adebajo S, Tun W, Sheehy M, Karlyn A, Njab J, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: implications for combination prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(2):221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merrigan M, Azeez A, Afolabi B, Chabikuli ON, Onyekwena O, Eluwa G, et al. HIV prevalence and risk behaviours among men having sex with men in Nigeria. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eluwa GI, Strathdee SA, Adebayo SB, Ahonsi B, Adebajo SB. A profile on HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among injecting drug users in Nigeria: Should we be alarmed? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127(1–3):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adebajo SB, Eluwa GI, Allman D, Myers T, Ahonsi BA. Prevalence of internalized homophobia and HIV associated risks among men who have sex with men in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16(4):21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston L, Saumtally A, Corceal S, Mahadoo I, Oodally F. High HIV and hepatitis C prevalence amongst injecting drug users in Mauritius: findings from a population size estimation and respondent driven sampling survey. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(4):252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston LG, Corceal S. Unexpectedly high injection drug use, HIV and hepatitis C prevalence among female sex workers in the Republic of Mauritius. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kriitmaa K, Testa A, Osman M, Bozicevic I, Riedner G, Malungu J, et al. HIV prevalence and characteristics of sex work among female sex workers in Hargeisa, Somaliland, Somalia. AIDS. 2010;24(2 Suppl):S61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rispel LC, Metcalf CA, Cloete A, Reddy V, Lombard C. HIV prevalence and risk practices among men who have sex with men in two South African cities. J Acquir immune. 2011;57(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: Results from the Soweto men’s study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:626–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston L, O’Bra H, Chopra M, Mathews C, Townsend L, Sabin K, et al. The associations of voluntary counseling and testing acceptance and the perceived likelihood of being HIV-infected among men with multiple sex partners in a South African township. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):922–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chopra M, Townsend L, Johnston L, Mathews C, Tomlinson M, Bra HO, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among high-risk heterosexual men with multiple sex partners : use of respondent-driven sampling. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(1):72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Townsend L, Rosenthal SR, Parry CDH, Zembe Y, Mathews C, Flisher AJ. Associations between alcohol misuse and risks for HIV infection among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12):1544–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsend L, Johnston LG, Flisher AJ, Mathews C, Zembe Y. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling to recruit high risk heterosexual men who have multiple female sexual partners: differences in HIV prevalence and sexual risk behaviours measured at two time points. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1330–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zembe YZ, Townsend L, Thorson A, Ekström AM. Predictors of inconsistent condom use among a hard to reach population of young women with multiple sexual partners in peri-urban South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townsend L, Zembe Y, Mathews C, Mason-Jones A. Estimating HIV prevalence and HIV-related risk behaviors among heterosexual women who have multiple sex partners using respondent-driven sampling in a high-risk community in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdelrahim MS. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of female sex workers in Khartoum, North Sudan. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl2):S55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston LG, Holman A, Dahoma M, Miller LA, Kim E, Mussa M, et al. HIV risk and the overlap of injecting drug use and high-risk sexual behaviours among men who have sex with men in Zanzibar (Unguja), Tanzania. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(6):485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahoma M, Johnston LG, Holman A, Miller LA, Mussa M, Othman A, et al. HIV and related risk behavior among men who have sex with men in Zanzibar, Tanzania: results of a behavioral surveillance survey. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hladik W, Barker J, Ssenkusu JM, Opio A, Tappero JW, Hakim A, et al. HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Kampala, Uganda—a respondent driven sampling survey. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soliman C, Rahman IA, Shawky S, Bahaa T, Elkamhawi S, El Sattar AA, et al. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of male injection drug users in Cairo, Egypt. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl2):S33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navadeh S, Mirzazadeh A, Mousavi L, Haghdoost A, Fahimfar N, Sedaghat A. HIV, HSV2 and syphilis prevalence in female sex workers in Kerman, South-East Iran; using respondent-driven sampling. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(12):60–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahfoud Z, Afifi R, Ramia S, El Khoury D, Kassak K, El Barbir F, et al. HIV/AIDS among female sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men in Lebanon: results of the first biobehavioral surveys. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kassak K, Mahfoud Z, Kreidieh K, Shamra S, Afifi R, Ramia S. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections among female sex workers and men who have sex with men in Lebanon: Prevalence, risk behaviour and immune status. Sex Health. 2011;8:229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahfoud Z, Kassak K, Kreidieh K, Shamra S, Ramia S. Distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes among injecting drug users in Lebanon. Virol J. 2010;7:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mirzoyan L, Berendes S, Jeffery C, Thomson J, Ben Othman H, Danon L, et al. New evidence on the HIV epidemic in Libya: why countries must implement prevention programs among people who inject drugs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(5):577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valadez JJ, Berendes S, Jeffery C, Thomson J, Ben Othman H, Danon L, et al. Filling the knowledge gap: measuring HIV prevalence and risk factors among men who have sex with men and female sex workers in Tripoli, Libya. PLoSOne.2013;8(6):e66701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnston LG, Alami K, El Rhilani MH, Karkouri M, Mellouk O, Abadie A, et al. HIV, syphilis and sexual risk behaviours among men who have sex with men in Agadir and Marrakesh, Morocco. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 3:iii45–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stulhofer A, Chetty A, Rabie RA, Jwehan I, Ramlawi A. The prevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and HIV-related risk-taking behaviors among Palestinian injecting drug users in the East Jerusalem Governorate. J Urban Heal. 2012;89(4):671–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stormer A, Tun W, Guli L, Harxhi A, Bodanovskaia Z, Yakovleva A, et al. An analysis of respondent driven sampling with injection drug users (IDU) in Albania and the Russian Federation. J Urban Heal. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elda S, Bani R. An analysis of HIV-related risk behaviors of men having sex with men (MSM), using respondent driven sampling (RDS), Albania. Int J Med. 2009;2(2):231–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bozicevic I, Lepej SZ, Rode OD, Grgic I, Jankovic P, Dominkovic Z, et al. Prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections and patterns of recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Zagreb, Croatia. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(7):539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bozicevic I, Rode OD, Lepej SZ, Johnston LG, Stulhofer A, Dominkovic Z, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Zagreb, Croatia. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(2):303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lepej SZ, Vrakela IB, Poljak M, Bozicevic I, Begovac J. Phylogenetic analysis of HIV sequences obtained in a respondent-driven sampling study of men who have sex with men. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2009;25(12):1335–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mills HL, Colijn C, Vickerman P, Leslie D, Hope V, Hickman M, Respondent driven sampling and community structure in a population of injecting drug users, Bristol, UK. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126(3):324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hope VD, Hickman M, Ngui SL, Jones S, Telfer M, Bizzarri M, et al. Measuring the incidence, prevalence and genetic relatedness of hepatitis C infections among a community recruited sample of injecting drug users, using dried blood spots. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:262–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Platt L, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Uusküla A, Parry JV, Rüütel K, et al. High HIV prevalence among injecting drug users in Estonia: implications for understanding the risk environment. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abel-Ollo K, Rahu M, Rajaleid K, Talu A, Ruutel K, Platt L, et al. Knowledge of HIV serostatus and risk behaviour among injecting drug users in Estonia. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):851–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vorobjov S, Uusküla A, Abel-Ollo K, Talu A, Rüütel K, Des Jarlais DC. Comparison of injecting drug users who obtain syringes from pharmacies and syringe exchange programs in Tallinn, Estonia. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uusküla A, Des Jarlais DC, Kals M, Rüütel K, Abel-Ollo K, Talu A, et al. Expanded syringe exchange programs and reduced HIV infection among new injection drug users in Tallinn, Estonia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uusküla A, Johnston LG, Raag M, Trummal A, Talu A, Des Jarlais DC. Evaluating recruitment among female sex workers and injecting drug users at risk for HIV using respondent-driven sampling in Estonia. J Urban Heal. 2010;87(2):304–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uusküla A, Fischer K, Raudne R, Kilgi H, Krylov R, Salminen M, et al. A study on HIV and hepatitis C virus among commercial sex workers in Tallinn. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(3):189–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Talu A, Rajaleid K, Abel-Ollo K, Rüütel K, Rahu M, Rhodes T, et al. HIV infection and risk behaviour of primary fentanyl and amphetamine injectors in Tallinn, Estonia: Implications for intervention. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berry M, Wirtz AL, Janayeva A, Ragoza V, Terlikbayeva A, Amirov B, et al. Risk factors for HIV and unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Almaty, Kazakhstan. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zohrabyan L, Johnston LG, Scutelniciuc O, Iovita A, Todirascu L, Costin T, et al. Determinants of HIV infection among female sex workers in two cities in the Republic of Moldova: the role of injection drug use and sexual risk. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8): 2588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Busza J, Douthwaite M, Bani R, Scutelniciuc O, Preda M, Simic D. Injecting behaviour and service use among young injectors in Albania, Moldova, Romania and Serbia. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(5):423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zohrabyan L, Johnston L, Scutelniciuc O, Iovita A, Todirascu L, Costin T, et al. HIV, hepatitis and syphilis prevalence and correlates of condom use during anal sex among men who have sex with men in the Republic of Moldova. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baćak V, Laušević D, Mugoša B, Vratnica Z, Terzić N. Hepatitis C virus infection and related risk factors among injection drug users in Montenegro. Eur Addict Res. 2013;19:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Judd A, Rhodes T, Johnston LG, Platt L, Andjelkovic V, Simić D, et al. Improving survey methods in sero-epidemiological studies of injecting drug users: a case example of two cross sectional surveys in Serbia and Montenegro. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eritsyan KU, Levina OS, White E, Smolskaya TT, Heimer R. HIV prevalence and risk behavior among injection drug users and their sex partners in two Russian cities. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29(4):687–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Niccolai LM, Shcherbakova IS, Toussova OV, Kozlov AP, Heimer R. The potential for bridging of HIV transmission in the russian federation: Sex risk behaviors and HIV prevalence among drug users (DUs) and their non-du sex partners. J Urban Heal. 2009;86(1):131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paintsil E, Verevochkin SV, Dukhovlinova E, Niccolai L, Barbour R, White E, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among drug injectors in St Petersburg, Russia: Social and molecular epidemiology of an endemic infection. Addiction. 2009;104:1881–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iguchi MY, Ober AJ, Berry SH, Fain T, Heckathorn DD, Gor-bach PM, et al. Simultaneous recruitment of drug users and men who have sex with men in the united states and Russia using respondent-driven sampling: Sampling methods and implications. J Urban Heal. 2009;86(1):5–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Djonic D, Djuric M, Bassioni-Stamenic F, McFarland W, Knezevic T, Nikolic S, et al. HIV-related risk behaviors among roma youth in Serbia: Results of two community based surveys. J Adolesc Heal. 2013;52(2):234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taran YS, Johnston LG, Pohorila NB, Saliuk TO. Correlates of HIV risk among injecting drug users in sixteen Ukrainian cities. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pando MA, Balán IC, Marone R, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Squiquera L, et al. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men recruited by RDS in Buenos Aires, Argentina: High HIV and HPV infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pando M, Marone R, Balan I, Dolezal C, Squiquera L, Picconi A, et al. HIV and STI prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM) recruited through respondent driven sampling (RDS) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Retrovirology. BioMed Central; 2009;6 Suppl 3:P103. [Google Scholar]